Abstract

LL-37, a cationic antimicrobial peptide, has numerous immune-modulating effects. However, the identity of a receptor(s) mediating the responses in immune cells remains uncertain. We have recently demonstrated that LL-37 interacts with the αMI-domain of integrin αMβ2 (Mac-1), a major receptor on the surface of myeloid cells, and induces a migratory response in Mac-1-expressing monocyte/macrophages as well as activation of Mac-1 on neutrophils. Here, we show that LL-37 and its C-terminal derivative supported strong adhesion of various Mac-1-expressing cells, including HEK293 cells stably transfected with Mac-1, human U937 monocytic cells and murine IC-21 macrophages. The cell adhesion to LL-37 was partially inhibited by specific Mac-1 antagonists, including mAb against the αM integrin subunit and neutrophil inhibitory factor, and completely blocked when anti-Mac-1 antibodies were combined with heparin, suggesting that cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans act cooperatively with integrin Mac-1. Coating both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria with LL-37 significantly potentiated their phagocytosis by macrophages, and this process was blocked by a combination of anti-Mac-1 mAb and heparin. Furthermore, phagocytosis by wild-type murine peritoneal macrophages of LL-37-coated latex beads, a model of foreign surfaces, was several fold higher than that of untreated beads. By contrast, LL-37 failed to augment phagocytosis of beads by Mac-1-deficient macrophages. These results identify LL-37 as a novel ligand for integrin Mac-1 and demonstrate that the interaction between Mac-1 on macrophages and bacteria-bound LL-37 promotes phagocytosis.

Keywords: LL-37, integrin αMβ2, Mac-1, CD11b/CD18, phagocytosis, opsonin

INTRODUCTION

LL-37, a member of the cathelicidin family of mammalian host defense peptides, and the only representative of this group in humans, exerts numerous immune-modulating effects in response to infections and other changes in the status of immune system (reviewed in1). It is derived as a peptide of 37 amino acids by a proteolytic cleavage in the C-terminal part of its precursor cationic antimicrobial protein-18 (hCAP-18; molecular weight 18 kDa) when this protein is secreted from cells during the immune-inflammatory response.2 While initially isolated from neutrophils, hCAP-18/LL-37 has subsequently been found in other blood cells including monocyte/macrophages, eosinophils, natural killer, T, and B cells in addition to mast cells and various epithelial cells.3 The biological significance of LL-37 in innate host defense has been established in studies of its mouse homologue CRAMP, which shares with LL-37 similar gene structure as well as tissue distribution: mice null for the CRAMP gene are more susceptible to streptococcal infections.4 Furthermore, systemic expression of the hCAP-18/LL-37 gene or LL-37 injection protects rodents from septic death.4-6

Similar to other antimicrobial cationic peptides, LL-37 consists mainly of positively charged and hydrophobic residues and has a propensity to fold into the amphipathic α-helix in physiologically relevant buffers and environments mimicking biological membranes. The cationic and amphipathic nature of antimicrobial peptides is generally associated with their bactericidal activity: the overall positive charge endows them with the ability to bind to the negatively charged bacterial wall and the anionic cell membrane (reviewed in7,8). After the insertion into the membrane, antimicrobial peptides are thought to disrupt the integrity of the bilayer resulting in killing of bacteria. Although the direct bactericidal activity of LL-37 has been documented in vitro under low salt conditions and in the absence of divalent cations like Ca2+ and Mg2+, it is significantly reduced when assayed in physiologically relevant media and at the peptide concentrations that are found at sites of infection or inflammation.6 These observations led to an idea that the membrane-targeting activity of LL-37 may not be the primary function of this peptide.6,9

Numerous studies have demonstrated that LL-37 exerts a multitude of effects on the immune cells in vitro (reviewed in10,11). LL-37 has a chemotactic effect, acting upon and inducing migration of human peripheral blood monocytes, neutrophils and T cells.12 It was shown to modulate expression of hundreds of genes in monocytes and other cells, including those for chemokines and chemokine receptors.13 Human neutrophils exposed to LL-37 increase the production of reactive oxygen species14 and exhibit delayed apoptosis.15 Thus, during infection, LL-37 released by degranulation of neutrophils or secreted from other cells would be expected to modulate the innate immune response through a variety of ways. However, the mechanisms underlying these LL-37 responses have not been well characterized and to date, several receptors were reported to associate with LL-37-induced immunomodulation.12,16-19

We have recently characterized the recognition specificity of integrin αMβ2 (Mac-1, CD11b/CD18), a receptor with broad ligand binding specificity expressed on neutrophils and monocyte/macrophages, and identified structural motifs present in many Mac-1 ligands.20 In particular, the αMI-domain, a ligand-binding region of Mac-1, has affinity for short 6-9 mer amino acid sequences containing a core of basic residues flanked by hydrophobic residues in which negatively charged residues are strongly disfavored. The binding motifs for Mac-1 can be coded as HyBHy, HyHyBHy, HyBHyHy and HyHyBHyHy, where Hy represents any hydrophobic residue and B is either arginine or lysine. Other amino acids also can be found, but in general their proportion within the Mac-1-binding motifs is very small. Inspection of the LL-37 sequence revealed that it contains several putative Mac-1 recognition sites and may represent a ligand for Mac-1. Indeed, we have shown that recombinant αMI-domain bound several overlapping LL-37-derived peptides and the full-length LL-37 peptide induced Mac-1-dependent migration of monocyte and macrophages as well as neutrophil activation.20

In the present study, we have further examined the interaction of LL-37 with Mac-1-expressing cells. These studies were initiated to test the hypothesis that cationic LL-37, when deposited on the anionic bacterial surface, would serve as an adhesive ligand for Mac-1 on macrophages and promote phagocytosis. The results demonstrate that LL-37 is a potent opsonin which augments phagocytosis of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive strains through a cooperative binding of integrin Mac-1 and heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the surface of macrophages.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptides, Proteins and Monoclonal antibodies

The LL-37 peptide (1LLGDFFRKSKEKIGKEFKRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES37), its C-terminal part (residues 18-37; termed K18-37), and LL-37-GY containing two additional C-terminal residues Gly-Tyr were obtained from AnaSpec, Inc (San Jose, CA) and Peptide 2.0 (Chantilly, VA). Alternatively, recombinant LL-37 was prepared as described.21 Briefly, LL-37 was expressed as a fusion protein with glutathione S-transferase. The cDNA of LL-37 (from True clone, Rockville, MD) was cloned in the pGEX-4T-1 expression vector (GE Healthcare). Recombinant GST-LL-37 was purified from a soluble fraction of E. coli lysates by affinity chromatography using glutathione-agarose. LL-37 was separated from GST by digestion with thrombin followed by gel-filtration on Sephadex G-25. The isolated peptide was analyzed by Western blotting using polyclonal antibody sc-50423 (Santa Cruz; Dallas, TX). LL-37-GY was labeled with Iodine-125 using IODO-GEN (Thermo Scientific Pierce Protein Research Products, Rockford, IL) to the specific activity of 6×109 cpm/μmole. Fibrinogen, depleted of fibronectin and plasminogen, was obtained from Enzyme Research Laboratories (South Bend, IN). Recombinant αMI-domain (residues Glu123-Lys218) was prepared as previously described.22 The monoclonal antibodies (mAb) 44a, directed against the human αM integrin subunit, mAb IB4, against the human β2 integrin subunit, and mAb M1/70, against the mouse αM subunit were, purified from the conditioned media of hybridoma cells obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) using protein A agarose. Mouse (G3A1) mAb IgG1 isotype control for mAb 44a was from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA) and rat IgG2b (MCA1125) isotype control for mAb M1/70 was from BioRad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). The anti-β1 mAb AIIB2 was from DSHB (Iowa City, IA). BSA, PVP, heparin (sodium salt; from porcine intestinal mucosa), and poly-L-lysine (m.w. 90000) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Calcein-AM and fluorescent latex beads (FluoroSpheres, 1 μm) were from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA).

Synthesis of Cellulose-bound Peptide Libraries

The FALL-39-derived peptide library assembled on a single cellulose membrane support was prepared by parallel spot synthesis as previous described.23,24 The membrane-bound peptides were tested for their ability to bind the αMI-domain according to a previously described procedure.23 In brief, the membrane was blocked with 1% BSA and then incubated with 10 μg/ml of 125I-labeled αMI-domain in TBS containing 1 mM MgCl2. After washing, the membrane was dried and the αMI-domain binding was visualized by autoradiography.

Cells

Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293) and HEK293 cells stably expressing integrin Mac-1 were previously described.25,26 The cells were maintained in DMEM (Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics. U937 human monocytic cells were grown in RPMI containing 10 % FBS and antibiotics. The THP-1 human monocytic cell line was purchased from American Tissue Type Culture Collection and cultured in RPMI containing 10% FBS, antibiotics and 0.05mM 2-mercaptoethanol. The THP-1 cells were differentiated into macrophages by adding 10 ng/ml of PMA into the medium for 48 h as previously described.27 The IC-21 murine macrophage cell, Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus 25923 (ATCC 25923) and Escherichia coli MG-1655 (ATCC 700926) were from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Resident peritoneal leukocytes were obtained from 8-week old wild-type C57BL/6 and Mac-1−/− mice (The Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) by lavage using cold PBS containing 5 mM EDTA. The population of wild-type leukocytes contained 46.3±2.7% and 44.1±3.6% of macrophage and lymphocytes, respectively, and that obtained from Mac-1−/− mice consisted of 37.3% macrophages and 53±2.9% lymphocytes. Macrophages were obtained by plating a total population of peritoneal leukocytes on glass cover slides for 2 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 followed by the removal of nonadherent cells (mainly lymphocytes) that resulted in the enrichment of adherent macrophages.

Cell Adhesion Assays

Adhesion assays were performed essentially as described previously.25,26 Briefly, the wells of 96-well microtiter plates (Immulon 4HBX, Thermo Labsystems, Franklin, MA) were coated with various concentrations of LL-37 or LL-37-derived peptides for 3 h at 37 °C and postcoated with 1.0% PVP for 1 h at 37 °C. Fibrinogen was coated at 2.5 μg/ml. Cells were labeled with 5 μM calcein for 30 min at 37 °C and washed twice with Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) containing 0.1% BSA. Aliquots (100 μl) of labeled cells (5×105/ml) were added to each well and allowed to adhere for 30 min at 37 °C. The nonadherent cells were removed by two washes with PBS. Fluorescence was measured in a CytoFluorII fluorescence plate reader (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). In inhibition experiments, cells were mixed with different concentrations of mAbs, NIF, heparin or the K18-37 peptide for 15 min at 22 °C before they were added to the wells coated with adhesive substrates.

Phagocytosis Assays

A suspension of fluorescein-labeled S. aureus particles (4×107/ml) (pHrodo® Green, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was incubated with different concentrations of LL-37 or K18-37 for 20 minutes at 22 °C, then unbound peptide was removed by centrifugation. IC-21 murine macrophages (106/ml) were mixed with peptide-coated S. aureus particles. After incubating for 60 minutes at 37 °C, nonphagocytosed of S. aureus particles were separated from macrophages by filtering the suspension using Transwell inserts with a pore size of 3.0 μm (Costar, Corning, Tewksbury, MA). Macrophages were transferred to wells of 96-well microtiter plates, and trypan blue (0.2%) was applied to wells to quench the fluorescence of any remaining S. aureus outside of macrophages. The ratio of bacterial particles per macrophage was quantified taking photographs of three fields for each well using a Leica DM4000 B microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL) with a 20× objective.

Phagocytosis by adherent macrophages was performed using FITC-labeled bacteria. To label E. coli, bacteria were grown overnight and diluted with 50 mM NaHCO3, pH 8.5 to OD=1.5. FITC was dissolved in DMSO and added to 0.5 ml E. coli suspensions to a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml. Suspensions were incubated for 1 h at 22 °C. Labeled bacteria were washed with 4×1 ml PBS by centrifugation at 1800 × g for 5 min. FITC-labeled E. coli (100 μl, 3×108 particles/ml) were incubated with LL-37 for 30 min at 37 °C and washed with RPMI by centrifugation at 1800 × g for 5 min to remove unbound peptide. The pellet was re-suspended in RPMI+10% FBS at the concentration of 107 bacterial particles/ml. For control experiments, media was substituted for LL-37, but all other aspects of the procedure were the same. For selected experiments, fluorescent 1.0 μM latex beads were incubated with LL-37, washed, and applied at 2.5×106 to wells containing macrophages. IC-21 murine macrophages, macrophages isolated from the mouse peritoneum and differentiated THP-1 human macrophages were re-suspended in RPMI+10% FBS and cultured in Costar 48-well plates (2.5×105/well) for 3-5 h at 37 °C. After media was aspirated, adherent cells were washed and incubated with 0.5 ml FITC-labeled E. coli suspensions, S. aureus particles or fluorescent latex beads for 1 h at 37 °C. Cells were washed with 3×1 ml PBS and phagocytosed bacteria or beads were counted in the presence of trypan blue.

In comparative studies of LL-37-induced phagocytosis by macrophages isolated from the peritoneum of wild-type and Mac-1−/− mice, the cells were allowed to adhere to glass cover slides for 2 h at 37 °C. After removing of nonadherent cells, fluorescent latex beads treated with LL-37 were added to the cells and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 2% parafolmaldehyde and beads counted. Animal studies were carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Arizona State University (protocol number 13-1271R) and Mayo Clinic in Arizona (protocol number A22313).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± S.E. The statistical differences between two groups were determined using a Student’s t-test from SigmaPlot 11.0 software (Systat Software, San Jose, CA). For multiple comparisons, the Bonferroni correction method was used. Differences were considered significant at P < .05.

RESULTS

Analyses of the αMI-domain binding capacity of the FALL-39-derived peptides

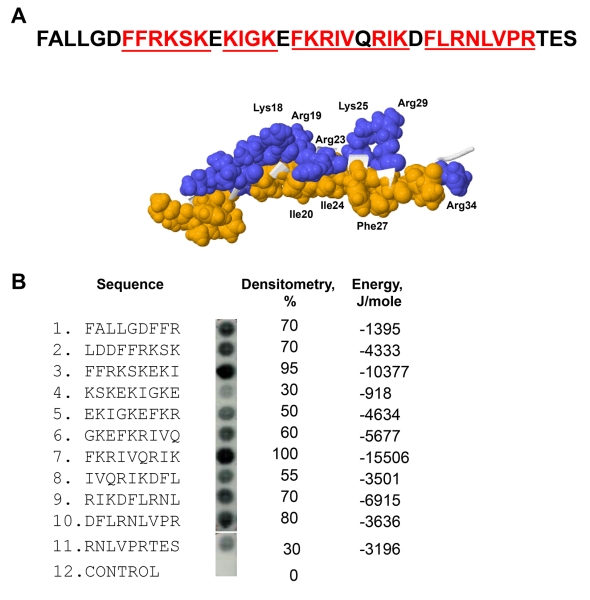

We previously screened a small peptide library consisting of eleven 9-mer peptides spanning the sequence of LL-37 for binding of recombinant αMI-domain.20 A remarkable feature of LL-37 is that ten overlapping peptides that bound the αMI-domain formed a continuous stretch. To validate these data, we synthesized an additional library spanning the sequence of FALL-39, an active derivative of LL-37, which includes the sequence of LL-37 and two additional N-terminal residues Phe and Ala present in the hCAP-18 cathelin precursor28 (Fig. 1A). Similar to the LL-37 library, all overlapping peptides in the FALL-39 scan bound the αMI-domain. Densitometric analyses of the library indicated that the most active peptides were present in spots 3 and 6 (Fig. 1B). The αMI-domain-binding peptides were analyzed by a previously developed algorithm, which determines the capacity of each peptide to interact with the αMI-domain.20 The program assigns each peptide the energy value which serves as a measure of probability that the αMI-domain binds this sequence: the lower the energy, the higher the likelihood that the sequence binds the αMI-domain. As determined from the analyses of numerous Mac-1 ligands, the peptides that strongly bind αMI-domain have energy values in the range of −20 to 2 kJ/mole.20 Based on the application of the algorithm, all peptides in the FALL-39 library had energies between −15.5 and −0.9 kJ/mole (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the two most active peptides in spots 3 and 6 had the lowest energies. The finding that overlapping peptides in the library form a continuous stretch containing strong αMI-domain recognition cores 5FFRKSK10, 12KIGK15, 17FKRIVQRIK25 and 27FLRNLVPR34 in which basic residues are surrounded or flanked by hydrophobic residues suggests that FALL-39 and LL-37 have the strong αMI-domain binding potential.

Figure 1. Characterization of the αMI-domain recognition motifs in the FALL-39 sequence.

(A) The amino acid sequence of FALL-39 and the 3D structure of LL-37 based on PDB Id: 2K6O. Positively charged (blue) and hydrophobic (tan) residues in the C-terminal part of the peptide are numbered. The underlined sequences denote the αMI-domain recognition patterns. (B) The peptide library derived from the FALL-39 sequence (left panel) consisting of 9-mer peptides with a 3 residue offset was incubated with 125I-labeled αMI-domain and the αMI-domain binding was visualized by autoradiography. Control, a spot containing only the β-Ala spacer used for the attachment of peptides to the cellulose membrane. The αMI-domain binding observed as dark spots was analyzed by densitometry (middle column). The numbers show the relative binding of the αMI-domain to peptides expressed as a percentage of the intensity of spot 3. The peptide energies (right column) that serve as a measure of probability each peptide can interact with the αMI-domain were calculated as described.20

LL-37 Supports Adhesion of the Mac-1-Expressing HEK293 Cells

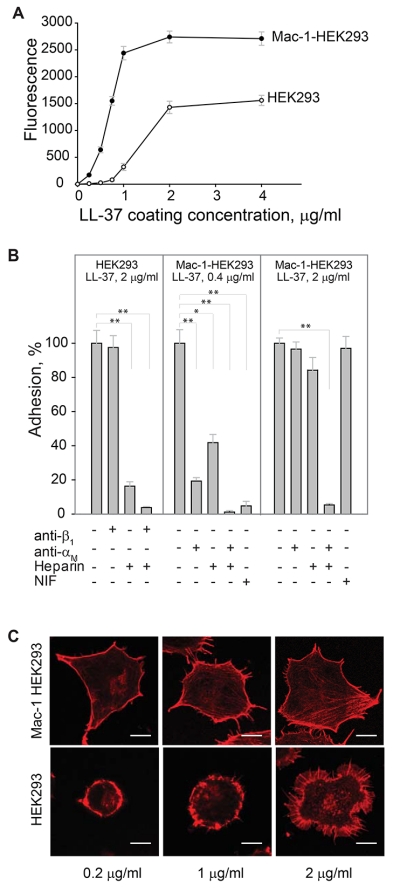

The interaction of the αMI-domain with LL-37-derived peptides suggests that LL-37 may support adhesion of Mac-1-expressing cells. To investigate this possibility, we performed adhesion with immobilized LL-37 using various Mac-1-expressing cells. As shown in Fig. 2A, LL-37 supported efficient adhesion of a model HEK293 cell line genetically engineered to stably express integrin Mac-1 (Mac-1-HEK293 cells). Cell attachment was dose dependent with saturable adhesion occurring at a coating concentration of 2 μg/ml. At this concentration, 52 ± 5% of added cells adhered to LL-37 (n=6). Using 125I-labeled LL-37-GY, we verified that peptide was immobilized on plastic in a concentration-dependent manner and supported adhesion (Supplemental Fig. S1). In contrast, no adhesion of wild-type HEK293 cells in the range of 0-1.0 μg/ml coating concentrations of LL-37 was observed (Fig. 2A). At higher coating concentrations (1-4 μg/ml), LL-37 supported adhesion of wild-type HEK293 cells; however, maximal adhesion did not reach the level attained with Mac-1-HEK293 cells (Fig. 2A). Human monocytic U937 cells naturally expressing Mac-1 also adhered to LL-37 in a concentration-dependent manner (not shown). The role of Mac-1 in the interaction of Mac-1-HEK293 cells with LL-37 was determined using function-blocking mAb 44a directed to the human αM integrin subunit. MAb 44a inhibited adhesion of the Mac-1-HEK293 cells by ~90% at the low (0.4 μg/ml) coating concentrations of LL-37 (Fig. 2B, middle panel). An isotype control IgG1 for mAb 44a was not active. At higher coating concentrations of LL-37, mAb 44a was less effective: at 0.5 μg/ml of LL-37, it inhibited adhesion by ~20% (not shown) and at 2 μg/ml, it produced only ~5% inhibition (Fig. 2B, right panel). The role of Mac-1 in mediating adhesion to LL-37 was also examined using neutrophil inhibitory factor (NIF), a specific inhibitor of the αMI-domain-ligand interactions.29 As seen with mAb 44a, NIF effectively blocked adhesion of the Mac-1-HEK293 cells to the low (0.4 μg/ml), but not high (≥2 μg/ml) concentrations of LL-37 (Fig. 2B). Partial inhibition of cell adhesion by specific anti-Mac-1 reagents and the fact that wild-type HEK293 cells were capable of mediating adhesion to LL-37 suggest that other receptors and/or cell structures contribute to cell attachment to LL-37.

Figure 2. LL-37 supports adhesion of the αMβ2-expresing cells.

(A) Aliquots (100 μl; 5×104/ml) of Mac-1-expressing HEK293 (Mac-1-HEK293) and wild-type HEK293 (HEK293) cells labeled with calcein were added to microtiter wells coated with different concentrations of LL-37 and postcoated with 1% PVP. After 30 min at 37 °C, nonadherent cells were removed by washing and fluorescence of adherent cells was measured in a fluorescence reader. A representative of 6 experiments in which two cell lines were tested side by side is shown. Data presented are means for triplicate determinations, and error bars represent S.E. (B) Wild-type HEK293 cells were preincubated with anti-β1 mAb (10 μg/ml), heparin (20 μg/ml) or their mixture for 15 min at 22 °C and added to wells coated with 2 μg/ml LL-37. Mac-1-HEK293 cells were preincubated with anti-αM mAb 44a (10 μg/ml), heparin (20 μg/ml) of their mixture and added to wells coated with 0.4 or 2 μg/ml LL-37. Adhesion was quantified as described above. Adhesion in the absence of Mac-1 inhibitors and heparin was assigned a value of 100%. Data shown are means ± S.E from 3-4 separate experiments with triplicate measurements. **p≤0.01, *p≤0.05 compared with control adhesion in the absence of inhibitors. (C) Mac-1-HEK293 (upper panel) and HEK293 cells (bottom panel) were plated on glass slides and allowed to adhere for 30 min at 37 °C. Nonadherent cells were removed and adherent cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde followed by staining with Alexa Fluor 546 phalloidin. The cells were imaged with a Leica SP5 laser scanning confocal microscope with a 63× objective.

It is well known that several integrins, including Mac-1, cooperate with cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) during cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix proteins.30,31 LL-37 is a highly positively charged molecule and is expected to bind negatively charged HSPGs. To investigate whether HSPGs on wild-type and Mac-1-HEK293 cells are required for cell adhesion to LL-37, we examined the effect of heparin. Heparin at 20 μg/ml was a strong inhibitor of adhesion of wild-type HEK293 cells at all coating concentrations of LL-37 (Fig. 2B). We also considered that β1 integrins, the major type of integrins on the surface of these cells26, may contribute to LL-37 recognition. However, we found no significant effect of anti-β1 mAb alone or in combination with heparin, suggesting that on the surface of wild-type HEK293 cells, HSPGs are mainly involved in LL-37 binding (Fig. 2B). With the Mac-1-HEK293 cells, heparin effectively inhibited cell adhesion to wells coated with the low concentration of LL-37 (0.4 μg/ml), and both anti-αM mAb 44a and heparin completely blocked adhesion (Fig. 2B). However, heparin was much less effective in blocking cell adhesion to the high (2 μg/ml) coating concentration of LL-37 (Fig. 2B). Nevertheless, when cells were treated with both mAb 44a and heparin, cell adhesion was inhibited by >95%.

Consistent with the role of Mac-1 in adhesion to LL-37, Mac-1-HEK293 cells spread in a concentration-dependent manner with the formation of stress fibers, as detected by staining for actin with Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated phalloidin (Fig. 2C, upper panel). By contrast, wild-type HEK293 cells remained round when plated on slides coated with the low concentrations of LL-37 (0.2-1.0 μg/ml) and spread at higher LL-37 concentrations (2 μg/ml). However, their morphology was entirely different from that of Mac-1-HEK293 cells with many actin-based filopodia/microspikes formed at the cell periphery (Fig. 2C, bottom panel). Together, these results identify LL-37 as an adhesive ligand for Mac-1 and indicate that on the surface of Mac-1-HEK293 cells, Mac-1 and HSPGs are involved in LL-37 recognition. They further suggest that the engagement of LL-37 by Mac-1 during adhesion transduces intracellular signaling leading to assembly of the actin cytoskeleton.

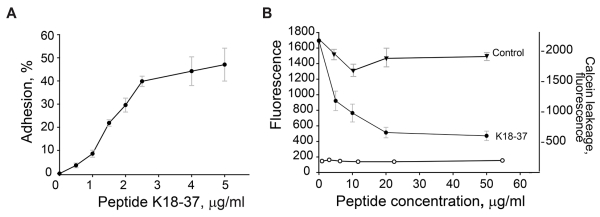

The C-terminal LL-derived peptide K18-37 supports and inhibits adhesion of Mac-1-expressing HEK293 cells

To investigate whether the C-terminal part of LL-37, 18KRIVQRIKDFLRNLVPRTES37, previously reported to be mainly responsible for the antimicrobial effect of LL-372,32, was involved in supporting adhesion, we examined dose dependency of adhesion of Mac-1-HEK293 cells to the K18-37 peptide. As shown in Fig. 3A, K18-37 supported efficient cell adhesion. Adhesion was concentration-dependent, and at 5 μg/ml, 47 ± 7% of added cells adhered to peptide (maximal adhesion). We next evaluated the effect of soluble K18-37 on adhesion of Mac-1-HEK cells to immobilized fibrinogen, a well-established Mac-1 ligand. It has been reported that αMI-domain binding peptides derived from different ligands inhibit Mac-1-mediated adhesion to the fibrinogen-derived D fragment20, which contains the γ383MKIIPFNRLTIG395 sequence, the prototype adhesive sequence for the αMI-domain33,34. As shown in Fig. 3B, preincubation of cells with soluble K18-37 dose-dependently inhibited cell adhesion with an IC50 of 6 μg/ml, indicating mutual exclusive binding of K18-37 to the αMI-domain. Control peptide DIDPKLKWD (11.1 kJ/mole) was inactive. Previous studies demonstrated that soluble LL-37 affects the membrane integrity of leukocytes, albeit at the high concentrations (>50 μg/ml).35,36 We reasoned that if soluble K18-37 also damaged the membrane it would result in the leakage of calcein and decreased fluorescence of adherent cells, giving a false impression of reduced adhesion. Therefore, in control experiments, we examined the effect of K18-37 by determining the leakage of calcein loaded into the Mac-1-HEK cells. As shown in Fig. 3B (left ordinate) peptide was not active even at 50 μg/ml (Fig. 3B). Thus, inhibition of cell adhesion by K18-37 is unlikely due to its effect on the cell membrane.

Figure 3. Adhesion of Mac-1-HEK293 and wild-type HEK293 cells to the LL-37-derived peptide K18-37.

(A) Aliquots (100 μl; 5×104/ml) of Mac-1-HEK293 cells were labeled with calcein and added to microtiter wells coated with different concentrations of K18-37. After 30 min at 37 °C, nonadherent cells were removed and adhesion was measured. Adhesion was expressed as percent of added cells. The data shown are means and S.E. from four experiments with triplicate determinations at each point. (B) Calcein-labeled Mac-1-HEK293 cells were incubated with different concentrations of K18-37 (●) or control peptide (▼) for 15 min at 22 °C and added to wells coated with 2.5 μg/ml fibrinogen and post-coated with 1% PVP. Adhesion (left ordinate) was determined as described in Fig. 2A legend. Right ordinate, Mac-1-HEK293 cells were treated with different concentrations of K18-37 for 15 min at 22 °C. Cells were centrifuged and fluorescence of cell supernatants determined (○). The data shown are the mean ± S.E. from two experiments each with triplicate determinations.

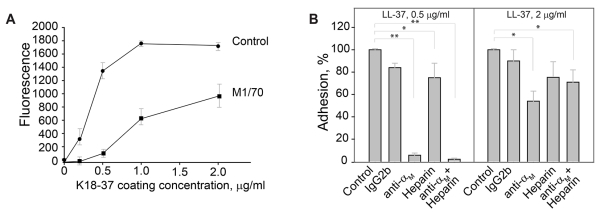

Adhesion of mouse macrophages to the K18-37 peptide is partly mediated by Mac-1 and HSPGs

The human LL-37 peptide has been shown to exert its immunomodulatory effects across a wide range of species, including mouse, rat, rabbit and human.13,37,38 Therefore, we examined the ability of LL-37 and K18-37 to support adhesion of the murine macrophage cell line IC-21. Macrophages strongly adhered to LL-37 and K18-37 (Fig. 4A, shown for K18-37). A similar pattern of inhibition by anti-αM antibodies that has been observed with human Mac-1-HEK293 cells was detected with IC-21 macrophages, i.e., while mAb M1/70 against the murine αM integrin subunit was a strong inhibitor of adhesion at the low coating concentrations of peptide (>90% inhibition at 0-0.5 μg/ml), it gradually lost its blocking potency as the coating concentration increased (Fig. 4A). At 2 μg/ml of K18-37, mAb M1/70 inhibited adhesion by 46 ± 9% (Fig. 4B). An isotype control IgG2b for mAb M1/70 had no significant effect. Pretreatment of cells with heparin (20 μg/ml) resulted in only partial inhibition of adhesion at both low (0.5 μg/ml) and high (2 μg/ml) coating concentration of K18-37 (25 ± 13 and 32 ± 12%) (Fig. 4B). Pretreatment of cells with both mAb M1/70 and heparin resulted in the complete inhibition of adhesion only at the low, but not high concentrations of K18-37 (Fig. 4B). These results suggest that on the surface of IC-21 macrophages Mac-1 and HSPGs are involved in adhesion to K18-37; however, other receptors and/or glycosaminoglycans may participate in peptide binding.

Figure 4. Adhesion of murine IC-21 macrophages to the LL-37-derived peptide K18-37.

(A) Calcein-labeled IC-21 macrophages were preincubated for 15 min at 22 °C with buffer (●) or 10 μg/ml mAb M1/70 (anti-αM) (■). Aliquots (5×104/0.1 ml) of cells were added to microtiter wells coated with different concentrations of K18-37 (0-2 μg/ml) and postcoated with 1% PVP. After 30 min at 37 °C, nonadherent cells were removed by washing and adhesion was determined. (B) IC-21 macrophages were preincubated with anti-αM mAb M1/70 (10 μg/ml), heparin (20 μg/ml) or their mixture and added to wells coated with 0.5 and 2 μg/ml K18-37. Adhesion was quantified as described above. Adhesion in the absence of inhibitors and heparin was assigned a value of 100 %. The data shown are the mean ± S.E. from 5-6 experiments each with triplicate determinations. **p≤0.01 and *p≤0.05 compared with control adhesion in the absence of inhibitors.

The Interaction of LL-37 with Bacteria Enhances Phagocytosis by Macrophages via Mac-1 and HSPGs

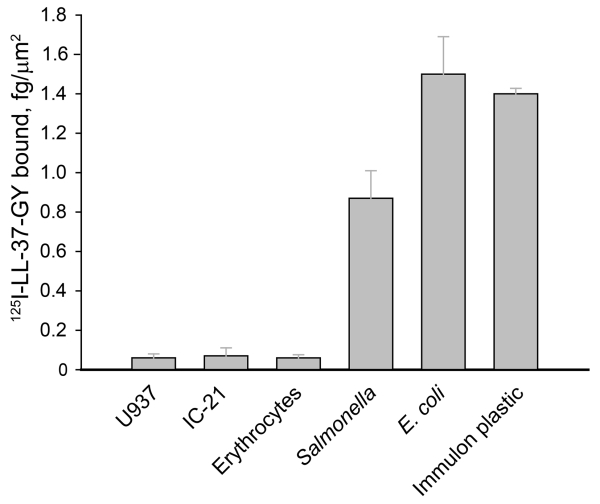

Since LL-37 supported efficient cell adhesion, we questioned whether LL-37 deposited on the bacterial surface can serve as an adhesive ligand for Mac-1 on macrophages thereby promoting bacterial phagocytosis. We first assessed the binding capacities of representative Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria for LL-37 and compared them with several mammalian cells. As shown in Fig. 5, U937, IC-21 and erythrocytes bound significantly less 125I-labeled LL-37-GY than the tested bacteria. At 5 μg/ml soluble peptide, the binding capacity of E. coli was 1.4±0.1 fg/μm2 similar to that of the plastic used in adhesion experiments. While Salmonella bound 1.8-fold less LL-37 than E. coli, the quantity of bound peptide was still ~17-fold higher than that associated with mammalian cells. The differential binding capacity of LL-37 is in agreement with the previously discussed characteristics that distinguish bacterial and mammalian cell membranes.8,39 These results suggest that the high density of LL-37 bound to the bacterial surface may support macrophage attachment.

Figure 5. Binding density of LL-37 on the surface of mammalian and microbial cells.

Cell suspensions were incubated with 5 μg/ml 125I-LL-37-GY for 20 min at 22 °C. Non-bound peptide was removed by centrifugation at 200g (mammalian cells) or 2000g (bacteria) for 10 min. The pellet was washed with PBS, re-suspended in 100 μl PBS and radioactivity was measured. The adsorption of 125I-LL-37-GY to Immulon wells is described in the legend to Supplemental Fig. 1. The data shown are the mean ± S.E. from 3 experiments each with duplicate measurements.

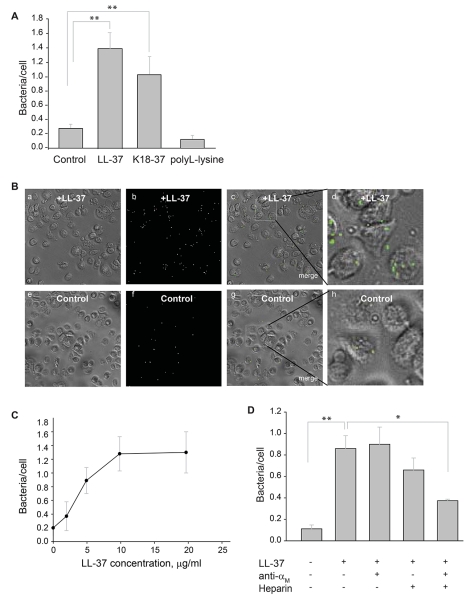

To assess whether LL-37 influences phagocytosis of bacteria by macrophages, suspensions of fluorescein-labeled S. aureus particles and E. coli were incubated with LL-37. After the removal of nonbound peptide, the coated bacteria were incubated with IC-21 macrophages for 60 min at 37 °C with the subsequent removal of nonphagocytosed particles. Before photographing the phagocytosed cells, trypan blue was added to quench the fluorescence of the remaining extracellular-bound bacterial particles. As shown in Fig. 6A and 6B, treatment of S. aureus with 5 μg/ml of LL-37 significantly augmented phagocytosis by macrophages. The C-terminal K18-37 peptide was also active in enhancing phagocytosis of S. aureus particles (Fig. 6A). Moreover, the effect of LL-37 was dose-dependent and saturable at 10 μg/ml (Fig. 6C; shown for E. coli).

Figure 6. Effect of LL-37 on phagocytosis of S. aureus particles and E. coli by suspensions of murine IC-21 macrophages.

(A) Fluorescent S. aureus particles (4×107/ml) were preincubated with LL-37 (5 μg/ml), K18-37 (10 μg/ml) or polyL-lysine (10 μg/ml) for 20 min at 22 °C. Soluble peptide was removed by centrifugation. Peptide-coated particles were incubated with suspensions of IC-21 macrophages (106/ml) for 60 min at 37 °C and nonphagocytosed particles were separated from cells by filtering the suspensions using a 3-μm pore Transwell inserts. Macrophages were transferred to wells of 96-well plates and trypan blue was added to wells. The ratio of bacterial particles per macrophage was quantified for five random fields per well using a 20× objective. Data shown are mean/cell ± S.E. from five or more experiments. **p≤0.01, compared with untreated control S. aureus. (B) Bright field (a,e), fluorescence (b,f) and merged (c,g) images of IC-21 macrophages incubated with LL-37-coated (a-c) or uncoated (e-g) control bacteria. The representative low power (20×) fields are shown. Enlarged images (d,h) of macrophages shown in the boxed areas in c and g. Phagocytosed bacterial particles are labeled in green. (C) Concentration-dependent effect of LL-37 on phagocytosis of E. coli by macrophages. Fluorescently labeled E. coli cells were incubated with different concentrations of LL-37 for 20 min at 22 °C. After the removal of nonbound peptide by centrifugation, LL-37-coated E. coli were incubated with IC-21 macrophages (106/ml) for 60 min at 37 °C. Phagocytosis was determined as in Fig. 6A. Data are expressed as mean ratios of bacteria per macrophage ± SE. A representative of three experiments is shown. (D) Fluorescent S. aureus particles were preincubated with LL-37 (5 μg/ml) for 20 min at 22 °C. Soluble peptide was removed by centrifugation. Peptide-coated bacterial particles were incubated with IC-21 macrophages (106/ml) in the presence of anti-αM mAb M1/70 (20 μg/ml), heparin (20 μg/ml) or their mixture. After 60 min incubation at 37 °C, nonphagocytosed S. aureus particles were removed and phagocytosis was measured as described above. Data shown are mean bacterial particles/cell ± S.E. of five random fields determined for each condition and are representative of 3 separate experiments. **p≤0.01, *p≤0.05

To investigate whether integrin Mac-1 and HSPGs on macrophages are involved in promoting phagocytosis of LL-37-coated bacteria, we examined the effects of anti-αM mAb M1/70 and heparin. On its own, mAb M1/70 did not inhibit LL-37-mediated phagocytosis (Fig. 6D). In addition, heparin only slightly decreased the number of phagocytosed bacterial particles. However, when macrophages were incubated with LL-37-coated particles in the presence of M1/70 and heparin, the peptide’s ability to boost phagocytosis was diminished by ~70%, consistent with the blocking effect of these reagents on cell adhesion. It should be noted though, that since the combination of heparin and anti-Mac-1 mAb did not produce complete inhibition, other receptors on IC-21 macrophages may contribute to LL-37-mediated phagocytosis.

Since positively charged residues in LL-37 are involved in the interaction with Mac-1 and HSPGs on macrophages, we examined whether other positively charged compounds can enhance phagocytosis. It is well-known that poly-L-lysine supports cell adhesion and this interaction is completely abolished by heparin. Therefore, we examined the effect of poly-L-lysine on phagocytosis of bacterial particles. No enhancement of phagocytosis by IC-21 macrophages of poly-L-lysine-coated particles was detected (Fig. 6A), indicating that the presence of basic residues alone is not sufficient for promoting phagocytosis, while underscoring the requirement for a specific signal provided by Mac-1 recognition motifs present in LL-37.

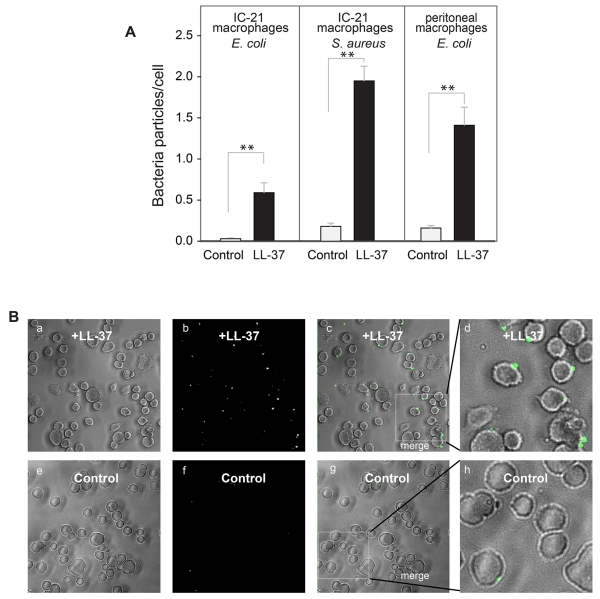

The effect of LL-37 (5 μg/ml) on phagocytosis of bacteria by adherent macrophages was also examined. As shown in Fig. 7A,B, phagocytosis of E. coli and S. aureus by adherent IC-21 macrophages increased by ~17- and 10-fold, respectively. In addition, LL-37 increased phagocytosis of E. coli and S. aureus by adherent murine peritoneal macrophages (Fig. 7A, shown for E. coli). Thus, LL-37 is capable of boosting phagocytosis of bacterial cells by both adherent and non-adherent macrophages.

Figure 7. Augmentation of phagocytosis of LL-37-coated bacteria by adherent macrophages.

(A) Fluorescently labeled S. aureus particles and E. coli cells were incubated with LL-37 (5 μg/ml) for 20 min at 22 °C. Soluble peptide was removed by centrifugation and LL-37-coated bacteria were subsequently incubated with adherent IC-21 macrophages or mouse peritoneal macrophages for 60 min at 37 °C. Data are expressed as mean ratios of bacteria per macrophage ± SE. The panels shown in A are representative of three or more experiments. **p≤0.01 compared with untreated control bacteria. (B) A representative experiment showing bright field (a,e), fluorescence (b,f) and merged images (c,g) of IC-21 macrophages exposed to LL-37-coated and uncoated control S. aureus.

LL-37 augments phagocytosis of plastic beads via Mac-1

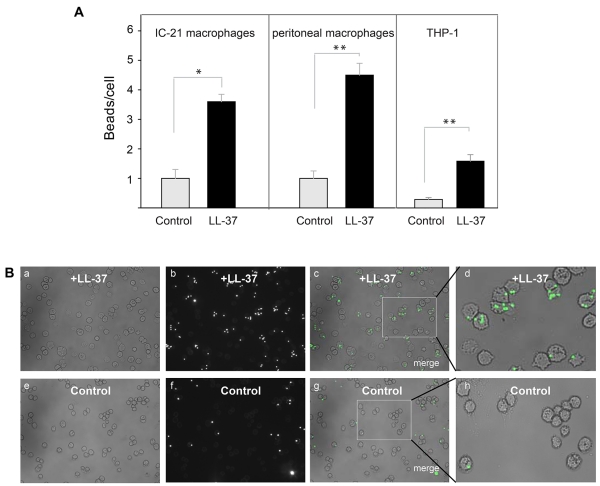

Its high affinity for plastic suggests that LL-37 may promote phagocytosis of foreign bodies. To examine this possibility we tested the ability of LL-37 to enhance phagocytosis of latex beads. Preliminary experiments using 125I-labeled LL-37-GY showed that at 10 μg/ml, peptide readily bound to the surface of beads (10.6±1.3 fg/μm2). Control and LL-37-treated fluorescent 1 μm beads were incubated with various cells, including IC-21 macrophages, peritoneal mouse macrophages and human THP-1 cells at a ratio of 10:1 for 30 min (a saturation time determined in preliminary experiments) and their phagocytosis was determined (Fig. 8A, B). Quantification of phagocytosed beads indicated that LL-37 augmented uptake by ~ 3.5-, 4.5- and 6-fold by IC-21, peritoneal macrophages and THP-1 cells, respectively.

Figure 8. Effect of LL-37 on phagocytosis of latex beads.

(A) Fluorescent latex beads (2.5×107/ml) were preincubated with LL-37 (10 μg/ml) for 20 min at 22 °C. Soluble peptide was removed from beads by high-speed centrifugation. Peptide-coated beads were incubated with IC-21 cells, mouse peritoneal macrophages or differentiated THP-1 cells for 30 min at 37 °C. Nonphagocytosed beads were separated from macrophages by centrifugation. The ratio of beads per macrophage was quantified from three fields of fluorescent images. Data shown are means ± S.E. of triplicate measurements and are representative of 3 experiments. **p≤0.01, *p≤0.05 compared with untreated beads. (B) Fluorescence of IC-21 macrophages exposed to LL-37-treated beads (a,b,c) or control untreated beads (e,f,g). Enlarged images of IC-21 macrophages showing phagocytosed LL-37-treated (d) or control (h) beads.

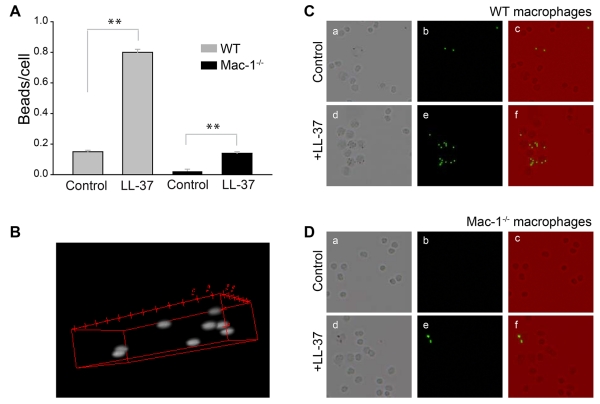

Further evidence supporting the role of Mac-1 in LL-37-induced phagocytosis was obtained using macrophages isolated from the peritoneum of wild-type and Mac-1−/− mice. Control and LL-37-coated fluorescent beads were added to adherent wild-type and Mac-1-deficient macrophages for 30 min at 37 °C and their phagocytosis was determined. In agreement with previous data that phagocytosis of Mac-1-deficient neutrophils is impaired40,41, phagocytosis of control beads by Mac-1-deficient macrophages was strongly reduced (Fig. 9A-C). Pretreatment of beads with LL-37 enhanced their uptake by wild-type macrophages by ~5 times. Phagocytosis of LL-37-coated beads by Mac-1-deficient macrophages was also increased; however, LL-37 failed to enhance phagocytosis to the level observed with wild-type macrophages (Fig. 9D). These data suggest that on the surface of macrophages, Mac-1 is the major receptor responsible for the opsonic function of LL-37.

Figure 9. Effect of LL-37 on phagocytosis of latex beads by Mac-1-deficient macrophages.

(A) Resident peritoneal macrophages were obtained from WT and Mac-1−/− mice as described in the Materials and Methods. LL-37-coated beads (prepared as in Fig. 8) were incubated with adherent macrophages for 30 min at 37 °C. Nonphagocytosed beads were washed, cells treated with trypan blue and the ratio of beads per macrophage was quantified from three fields of fluorescent images. Data shown are means ± S.E. of triplicate measurements from three experiments. **p≤0.01 compared with untreated control beads. (B) Representative confocal image illustrates phagocytosed beads inside a macrophage. (C, D) The representative fields of WT (C) and Mac-1-deficient (D) macrophages incubated with control and LL-37-coated beads. Bright field (a,d), fluorescence (b,e) and merged (c,f) images of WT and Mac-1-deficient macrophages.

DISCUSSION

Several mechanisms have been proposed that may account for the ability of the cathelicidin peptide LL-37 to protect the host from infections, including direct pathogen killing and eliciting numerous responses from the immune and other host cells. The immunomodulatory effects of LL-37 have been ascribed to its binding to and/or modulating activity of several unrelated cell surface receptors such as FPRL 1, EGFR, P2X7, and others.12,16-19,42 In this study, we demonstrated that LL-37 is a ligand for the major integrin receptor Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) on the surface of myeloid cells and found that coating of bacteria with LL-37 augments Mac-1-mediated phagocytosis of both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Importantly, LL-37 and its C-terminal K18-37 peptide enhanced phagocytosis at a range of concentrations that are not harmful to mammalian membranes. These observations establish a novel aspect of LL-37 action and suggest a role for this mechanism in the physiologic function of this host defense peptide.

The motivation to investigate the interaction of Mac-1 with LL-37 was our recent finding that LL-37 binds the αMI-domain, a ligand-binding region of Mac-1, induces a potent migratory response of Mac-1-expressing monocytes and macrophages and activates Mac-1 on the surface of neutrophils.20 Integrin Mac-1 is a member of the β2 subfamily of leukocyte integrin adhesion receptors and the major receptor on the surface of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages. This receptor contributes to leukocyte adhesion to and diapedesis through the inflamed endothelium and controls leukocyte migration to sites of inflammation.40,41,43,44 Moreover, ligand engagement by Mac-1 initiates a variety of cellular responses, including phagocytosis, neutrophil degranulation and aggregation, expression of cytokines/chemokines and other pro- and anti-inflammatory molecules.40,41 Innumerable roles played by Mac-1 in leukocyte biology are thought to arise from its multiligand binding properties. Indeed, this receptor exhibits broad recognition specificity and is capable of binding an extremely diverse group of protein and non-protein ligands (reviewed in part in25). Screening a large number of the peptide libraries spanning the sequences of Mac-1 protein and peptide ligands for the αMI-domain binding has allowed us to determine the Mac-1 recognition motif(s).20 In particular, we found that the αMI-domain binds not to specific amino acid sequence(s), but rather has a preference for the sequence patterns consisting of a core of positively charged residues flanked by hydrophobic residues. Analyses of the LL-37 sequence showed that it contains several potential αMI-domain recognition cores and this prediction was experimentally confirmed.20 Furthermore, in the present study, we corroborated these data by synthesizing the library of the longer LL-37 derivative, FALL-39 (Fig. 1). The interaction of the αMI-domain with LL-37 also was recently reported by Zhang et al45 who used surface plasmon resonance and biolayer interferometry. Interestingly, no interaction of the αMI-domain with the 13-mer LL-37 derived peptide FKRIVQRIKDFLR (FK-13) was found 45. This result appears to conflict with our data showing that the shorter 9-mer peptide FKRIVQRIK was the most active αMI-domain binding peptide in the library (Fig. 1). This discrepancy may potentially arise from a high density of peptides within the spots in the library that would favor the interaction with the αMI-domain or other differences in the experimental format used. However, an alternative explanation, which is supported by our previous studies, may be that FK-13, in contrast to FKRIVQRIK, contains Asp. Indeed, we showed that negatively charged residues were strongly disfavored in the population of the αMI-domain binding peptides20. Further studies of the LL-37 derived sequences and other Mac-1 ligands may help to define the binding specificity of the αMI-domain.

The role of LL-37 in combating bacterial assault has been shown in several models of infection6,45; however, the precise mechanism by which LL-37 exerts this protective effect has not been determined. Given its ability to directly kill pathogens in vitro, LL-37 was surmised to exert its effect by inserting into and disrupting the bacterial membrane. However, the validity of this mechanism in vivo has been questioned because the direct bactericidal activity was often observed only under low salt conditions and with relatively high concentrations of the peptide.6 In the presence of physiological salt concentrations and divalent cations, the antimicrobial activity of LL-37 was significantly reduced and in the presence of tissue-culture medium, the peptide had no cytotoxic activity against S. aureus or Salmonella typhimurium even at concentrations as high as 100 μg/ml.6,9 The high concentrations of LL-37 that are bactericidal in vitro have been detected in several locations during infection, for example, in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.46 However, such concentrations would seem to not only kill bacteria but also damage neighboring host cells. In this regard, it was previously reported that LL-37 can affect membrane integrity.35,36 Our data that LL-37 at 10 μg/ml induced a small calcein leakage (~3-fold the background level of control untreated cells; data not shown) is in keeping with the harmful effect of high concentrations of the peptide on mammalian cells. While host cells may suffer during the bacterial attack, it is still difficult to imagine an expedient host defense mechanism that turns not only on invaders but also on the host. The defense in which LL-37 spares host cells would seem by far more advantageous. From this perspective, the various immunomodulatory effects of LL-37 observed in standard tissue culture media or whole human blood in vitro6,9 may be a more rational explanation for its protective properties, especially in view of the modest concentrations of LL-37 in vivo. Furthermore, the process in which LL-37 marks the bacterial surface for recognition by macrophages to augment phagocytosis, as described in the present study, would primarily target bacteria rather than host cells. It is well established that the differences in the lipid composition between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell membranes, and in particular, the much higher concentration of negatively charged lipids on the surface of a bacterial cytoplasmic membrane and the presence of anionic lipids on the outer leaflet of Gram-negative bacteria allow host defense peptides to preferentially interact with bacterial membranes.8,39 This property, however, may be mainly utilized to opsonize rather than kill bacteria. In this respect, it is worth noting that in the present study the concentrations of LL-37 (1-5 μg/ml) that have been found to enhance bacterial phagocytosis were significantly lower than the minimal inhibitory concentrations (~30-100 μg/ml) required for bacterial killing in physiologically relevant buffers.6,47,48

LL-37 seems to be ideally suited to perform the opsonic function. First, its high positive charge (+6) facilitates the electrostatic interaction with negatively charged phospholipid headgroups of the bacterial surface.8 Second, when immobilized on the bacterial surface LL-37 serves as a ligand for Mac-1, a well-known phagocytic receptor.41,49 Third, the relatively small size of LL-37 would create a higher density on the bacterial surface compared to other known opsonins, for example, the complement pathway product iC3b, which is, intriguingly, another Mac-1 ligand.50 Fourth, it appears that numerous positively charged residues present in LL-37 are involved in the interaction with macrophage HSPGs, which may strengthen the interaction with the LL-coated bacterial surface. It is worth noting, though, that the positive charge of the polypeptides on its own is not sufficient to induce phagocytosis. This idea is supported by the data that poly-L-lysine was not active in promoting phagocytosis (Fig. 6). This is consistent with the hypothesis that the specific interaction of LL-37 with Mac-1 is required to transduce a signal for phagocytosis.

The efficiency of bacterial phagocytosis critically depends upon the opsonization of pathogen as well as the state of macrophage activation. Previous studies reported that several neutrophil-derived granule proteins/peptides opsonize bacteria resulting in enhanced phagocytosis.51,52 With regard to LL-37, it was shown that opsonization of oral Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans with the peptide resulted in increased phagocytosis by murine macrophages53 and an uptake of LL-37-coated polysterene beads by nondifferentiated primary human monocytes was increased compared to uncoated beads.45 On the other hand, bacterial phagocytosis was also shown to be augmented by pretreatment of macrophages with neutrophil secretion products,54 including LL-37.27 In two latter studies, pretreatment of macrophages with the neutrophil secretion or with LL-37 was followed by their washing before addition of the bacteria; therefore, direct activation of macrophages was apparently responsible for enhanced phagocytosis. In our studies, we have used a reverse experimental format, i.e. pretreatment of bacteria with LL-37 followed by their extensive washing before addition to macrophages. Therefore, opsonization rather than activation was responsible for the increased phagocytosis. It is well established that prior activation of Mac-1 is required for its full phagocytic function.55 Therefore, the results of the present study in conjunction with our previous findings showing that LL-37 activates Mac-1 on the surface of neutrophil20 suggest that LL-37 may play a dual role, i.e. serving as an opsonin and as activator of Mac-1 on phagocytes.

The broad ligand binding specificity exhibited by Mac-1 and its affinity for peptides/proteins enriched in positively charged and hydrophobic residues suggest that many other cationic defense proteins/peptides may fulfill the opsonic function through binding of Mac-1. Indeed, screening of several proteins stored in neutrophil granules as well as mammalian cathelicidins and other cationic peptides showed that they bind the αMI-domain20 (and unpublished data). Consistent with this proposal, we have recently shown that the cationic peptide dynorphin A that was previously shown to enhance phagocytosis56 opsonizes bacteria and promotes phagocytosis through Mac-1.57 Since negatively charged residues are generally strongly disfavored in the Mac-1 recognition motifs, it is tempting to speculate that the absence of negatively charged residues in some cathelicidin peptides (for example, bovine SMAP-29 and BMAP-271) as compared to LL-37, may increase their Mac-1 binding activity. It is also possible that not only LL-37 but its precursor hCAP-18 or its cathelin domain, which also contain putative Mac-1 binding sites, may increase phagocytosis. Further studies of Mac-1 recognition motifs in cationic host defense peptides may help to determine whether they exhibit phagocytosis-promoting activity.

Considering the rapid emergence of bacterial strains resistant to conventional antibiotics and the exodus of many pharmaceutical companies from the field of antibiotic research and development there has been an extensive effort to introduce host defense peptides, including LL-37, in clinical practice for the treatment of infectious disease.58-60 As the development of therapeutics based on host defense peptides continues, it is important to gain a better understanding of every aspect of their action. Our finding that LL-37 is an opsonin which boosts uptake of bacteria by macrophages via a specific engagement of the professional phagocytic receptor Mac-1 provides new insights into the role of this peptide in host defense, but also leaves many questions. Resolving the problems of how the opsonic function of LL-37 is coordinated with other known activities of this peptide and the question whether other cationic proteins/peptides fulfill the phagocytic function via Mac-1 and if so, what is their relative potency, would be of particular interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Yishin Shi, the School of Life Sciences, ASU for providing Salmonella bacterial strains and advice.

Funding Source statement: This work was supported by the NIH grant HL 63199.

Footnotes

Presented at the Annual Meeting of Experimental Biology, March 28-April 1, 2015, Boston, and published in the abstract form in FASEB J., 29:571.15

Supporting Information Available

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zanetti M. The role of cathelicidins in the innate host defenses of mammals. In: Gallo RL, editor. Antimicrobial peptides in human health and disease. Horizon Bioscience; Norfolk, U.K.: 2005. pp. 15–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sorensen OE, Follin P, Johnsen AH, et al. Human cathelicidin, hCAP-18, is processed to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by extracellular cleavage with proteinase 3. Blood. 2001;97:3951–3959. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.12.3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gundmundsson GH, Agerberth B. Antimicrobial peptides in human blood. In: Gallo RL, editor. Antimicrobial peptides in human health and disease. Horizon Bioscience; Norfolk, U.K.: 2005. pp. 153–174. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bals R, Weiner DJ, Moscioni AD, Meegalla RL, Wilson JM. Augmentation of innate host defense by expression of a cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6084–6089. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.6084-6089.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cirioni O, Giacometti A, Ghiselli R, et al. LL-37 protects rats against lethal sepsis caused by gram-negative bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1672–1679. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.5.1672-1679.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowdish DME, Davidson DJ, Lau YE, Lee K, Scott MG, Hancock REW. Impact of LL-37 on anti-infective immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:451–459. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0704380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zasloff M. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature. 2002;415:389–395. doi: 10.1038/415389a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McPhee JB, Hancock RE. Function and therapeutic potential of host defence peptides. J Pept Sci. 2005;11:677–687. doi: 10.1002/psc.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowdish DM, Davidson DJ, Hancock REW. A re-evaluation of the role of host defence peptides im mammalian immunity. Curr Prot Pept Sci. 2008;6:35–51. doi: 10.2174/1389203053027494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finlay BB, Hancock RE. Can innate immunity be enhanced to treat microbial infections? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:497–504. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mookherjee N, Hancock REW. Cationic host defense peptides: Innate immune regulatory peptides as a novel approach for treating infections. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:922–933. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang D, Chen Q, Schmidt AP, et al. LL-37, the neutrophil granule- and epithelial cell-derived cathelicidin, utilizes formyl peptide receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) as a receptor to chemoattract human peripheral blood neutrophils, monocytes, a T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1069–1074. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scott MG, Davidson DJ, Gold MR, Bowdish DM, Hancock REW. The human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 is a multifunctional modulator of innate immune response. J Immunol. 2002;169:3883–3891. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng Y, Niyonsaba F, Ushio H, et al. Cathelicidin LL-37 induces the generation of reactive oxygen species and release of human alpha-defensins from neutrophils. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1124–1131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagaoka I, Tamura H, Hirata M. An antimicrobial cathelicidin peptide, human CAP18/LL-37, suppresses neutrophil apoptosis via the activation of formyl-peptide receptor-like 1 and P2X7. J Immunol. 2006;176:3044–3052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.3044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tjabringa GS, Aarbiou J, Ninaber DK, et al. The antimicrobial peptide LL-37 activates innate immunity at the airway epithelial surface by transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Immunol. 2003;171:6690–6696. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elssner A, Duncan M, Gavrilin M, Wewers MD. A novel P2X7 receptor activator, the human cathelicidin-derived peptide LL37, induces IL-1 beta processing and release. J Immunol. 2004;172:4987–4994. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.8.4987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Z, Cherryholmes G, Chang F, Rose DM, Schraufstatter I, Shively JE. Evidence that cathelicidin peptide LL-37 may act as a functional ligand for CXCR2 on human neutrophils. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:3181–3194. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subramanian H, Gupta K, Guo Q, Price R, Ali H. Mas-related gene X2 (MrgX2) is a novel G protein-coupled receptor for the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 in human mast cells: resistance to receptor phosphorylation, desensitization, and internalization. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:44739–44749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.277152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podolnikova NP, Podolnikov AV, Haas TA, Lishko VK, Ugarova TP. Ligand recognition specificity of leukocyte integrin αMβ2 (Mac-1, CD11b/CD18) and its functional consequences. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1408–1420. doi: 10.1021/bi5013782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moon JY, Henzler-Wildman KA, Ramamoorthy A. Expression and purification of a recombinant LL-37 from Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1351–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yakubenko VP, Solovjov DA, Zhang L, Yee VC, Plow EF, Ugarova TP. Identification of the binding site for fibrinogen recognition peptide γ383-395 within the αM I-domain of integrin αMβ2. J Biol Chem. 2001;275:13995–14003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lishko VK, Podolnikova NP, Yakubenko VP, et al. Multiple binding sites in fibrinogen for integrin αMβ2 (Mac-1) J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44897–44906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Podolnikova NP, Gorkun OV, Loreth RM, Lord ST, Yee VC, Ugarova TP. A cluster of basic amino acid residues in the γ370-381 sequence of fibrinogen comprises a binding site for platelet integrin αIIbβ3 (GPIIb/IIIa) Biochemistry. 2005;44:16920–16930. doi: 10.1021/bi051581d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yakubenko VP, Lishko VK, Lam SCT, Ugarova TP. A molecular basis for integrin αMβ2 ligand binding promiscuity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48635–48642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lishko VK, Yakubenko VP, Ugarova TP. The interplay between Integrins αMβ2 and α5β1 during cell migration to fibronectin. Exp Cell Res. 2003;283:116–126. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan M, van der Does AM, Tang X, Lindbom L, Agerberth B, Haeggstrom JZ. Antimicrobial peptide LL-37 promotes bacterial phagocytosis by human macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:971–981. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0513304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gudmundsson GH, Agerberth B, Odeberg J, Bergman T, Olsson B, Salcedo R. The human gene FALL39 and processing of the cathelin precursor to the antibacterial peptide LL-37 in granulocytes. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:325–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0325z.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moyle M, Foster DL, McGrath DE, et al. A hookworm glycoprotein that inhibits neutrophil function is a ligand of the integrin CD11b/CD18. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10008–10015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen N, Chen CC, Lau LF. Adhesion of human skin fibroblasts to Cyr61 is mediated through integrin α6β1 and cell surface sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24953–24961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003040200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schober JM, Chen N, Grzeszkiewicz T, et al. Identification of integrin aMb2 as an adhesion receptor on peripheral blood monocytes for Cyr61 and connective tissue growth factor, immediate-early gene products expressed in atherosclerotic lesions. Blood. 2002;99:4457–4465. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang G. Structure of human host defense cathelicidin LL-37 and its smallest antimicrobial peptide KR-12 in lipid micelles. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32637–32643. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805533200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ugarova TP, Solovjov DA, Zhang L, et al. Identification of a novel recognition sequence for integrin αMβ2 within the gamma-chain of fibrinogen. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22519–22527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flick MJ, Du X, Witte DP, et al. Leukocyte engagement of fibrin(ogen) via the integrin receptor αMβ2/Mac-1 is critical for host inflammatory response in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1596–1606. doi: 10.1172/JCI20741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johansson J, Gudmundsson GH, Rottenberg ME, Berndt KD, Agerberth B. Conformation-dependent antibacterial activity of the naturally occurring human peptide LL-37. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3718–3724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zelezetsky I, Pontillo A, Puzzi L, et al. Evolution of the primate cathelicidin. Correlation between structural variations and antimicrobial activity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19861–19871. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511108200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Niyonsaba F, Iwabuchi K, Someya A, et al. A cathelicidin family of human antibacterial peptide LL-37 induces mast cell chemotaxis. Immunology. 2002;106:20–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01398.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koczulla R, von Degemfeld G, Kupatt C, et al. An angiogenic role for the human peptide antibiotic LL-37/hCAP-18. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1665–1672. doi: 10.1172/JCI17545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matsuzaki K. Why and how are peptide-lipid interactions utilized for self-defense? Magainins and tachyplesins as archetypes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1462:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coxon A, Rieu P, Barkalow FJ, et al. A novel role for the beta 2 integrin CD11b/CD18 in neutrophil apoptosis: a homeostatic mechanism in inflammation. Immunity. 1996;5:653–666. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu H, Smith CW, Perrard J, et al. LFA-1 is sufficient in mediating neutrophil emigration in Mac-1 deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1340–1350. doi: 10.1172/JCI119293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuroda K, Okumura K, Isogai H, Isogai E. The Human Cathelicidin Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 and Mimics are Potential Anticancer Drugs. Front Oncol. 2015;5:144. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2015.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding ZM, Babensee JE, Simon SI, et al. Relative contribution of LFA-1 and Mac-1 to neutrophil adhesion and migration. J Immunol. 1999;163:5029–5038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Henderson RB, Lim LHK, Tessier PA, et al. The use of lymphocyte function-associated antigen (LFA)-1-deficient mice to determine the role of LFA-1, Mac-1, and α4 integrin in the inflammatory response of neutrophils. J Exp Med. 2001;194:219–226. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang X, Bajic G, Andersen GR, Christiansen SH, Vorup-Jensen T. The cationic peptide LL-37 binds Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) with a low dissociation rate and promotes phagocytosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1864:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaller-Bals S, Schulze A, Bals R. Increased levels of antimicrobial peptides in tracheal aspirates of newborn infants during infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:992–995. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.200110-020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chromek M, Slamova Z, Bergman P, et al. The antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin protects the urinary tract against invasive bacterial infection. Nat Med. 2006;12:636–641. doi: 10.1038/nm1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Overhage J, Campisano A, Bains M, Torfs EC, Rehm BH, Hancock RE. Human host defense peptide LL-37 prevents bacterial biofilm formation. Infect Immun. 2008;76:4176–4182. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00318-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ross GD, Lambris JD. Identification of a C3bi-specific membrane complement receptor that is expressed on lymphocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and erythrocytes. J Exp Med. 1982;155:96–110. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ross GD, Cain JA, Lachmann PJ. Membrane complement receptor type three (CR3) has lectin-like properties analogous to bovine conglutinin as functions as a receptor for zymosan and rabbit erythrocytes as well as a receptor for iC3b. J Immunol. 1985;134:3307–3315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heinzelmann M, Platz A, Flodgaard H, Miller FN. Heparin binding protein (CAP37) is an opsonin for Staphylococcus aureus and increases phagocytosis in monocytes. Inflammation. 1998;22:493–507. doi: 10.1023/a:1022398027143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fleischmann J, Selsted ME, Lehrer RI. Opsonic activity of MCP-1 and MCP-2, cationic peptides from rabbit alveolar macrophages. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1985;3:233–242. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(85)90035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sol A, Ginesin O, Chaushu S, et al. LL-37 opsonizes and inhibits biofilm formation of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans at subbactericidal concentrations. Infect Immun. 2013;81:3577–3585. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01288-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soehnlein O, Kenne E, Rotzius P, Eriksson EE, Lindbom L. Neutrophil secretion products regulate anti-bacterial activity in monocytes and macrophages. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;151:139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ross GD, Vetvicka V. CR3(CD11b,CD18): a phagocyte and NK cell membrane receptor with miltiple ligand specificities and functions. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;92:181–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb03377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ichinose M, Asai M, Sawada M. Enhancement of phagocytosis by dynorphin A in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Neuroimmunol. 1995;60:37–43. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(95)00050-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Podolnikova NP, Brothwell JA, Ugarova TP. The opioid peptide dynorphin A induces leukocyte responses via integrin Mac-1 (αMβ2, CD11b/CD18) Mol Pain. 2015;11:33. doi: 10.1186/s12990-015-0027-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang L, Harris SM, Falla TJ. Therapeutic applications of innate immunity peptides. In: Gallo RL, editor. Antimicrobial peptides in human health and disease. Horizon Bioscience; Norfolk, U.K.: 2005. pp. 331–360. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hancock RE, Sahl HG. Antimicrobial and host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1551–1557. doi: 10.1038/nbt1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duplantier AJ, van Hoek ML. The Human Cathelicidin Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 as a Potential Treatment for Polymicrobial Infected Wounds. Front Immunol. 2013;4:143. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.