ABSTRACT

Background

The pan‐Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support (COSTaRS) team developed 13 evidence‐informed protocols for symptom management.

Aim

To build an effective and sustainable approach for implementing the COSTaRS protocols for nurses providing telephone‐based symptom support to cancer patients.

Methods

A comparative case study was guided by the Knowledge to Action Framework. Three cases were created for three Canadian oncology programs that have nurses providing telephone support. Teams of researchers and knowledge users: (a) assessed barriers and facilitators influencing protocol use, (b) adapted protocols for local use, (c) intervened to address barriers, (d) monitored use, and (e) assessed barriers and facilitators influencing sustained use. Analysis was within and across cases.

Results

At baseline, >85% nurses rated protocols positively but barriers were identified (64‐80% needed training). Patients and families identified similar barriers and thought protocols would enhance consistency among nurses teaching self‐management. Twenty‐two COSTaRS workshops reached 85% to 97% of targeted nurses (N = 119). Nurses felt more confident with symptom management and using the COSTaRS protocols (p < .01). Protocol adaptations addressed barriers (e.g., health records approval, creating pocket versions, distributing with telephone messages). Chart audits revealed that protocols used were documented for 11% to 47% of patient calls. Sustained use requires organizational alignment and ongoing leadership support.

Linking Evidence to Action

Protocol uptake was similar to trials that have evaluated tailored interventions to improve professional practice by overcoming identified barriers. Collaborating with knowledge users facilitated interpretation of findings, aided protocol adaptation, and supported implementation. Protocol implementation in nursing requires a tailored approach. A multifaceted intervention approach increased nurses’ use of evidence‐informed protocols during telephone calls with patients about symptoms. Training and other interventions improved nurses’ confidence with using COSTaRS protocols and their uptake was evident in some documented telephone calls. Protocols could be adapted for use by patients and nurses globally.

Keywords: implementation, cancer, symptom management, nursing, knowledge translation tools, knowledge to action, case study

BACKGROUND

Oncology nurses are expected to follow guidelines or protocols when providing telephone‐based symptom management to patients (Canadian Nurses Association [CNA], 2007; Coleman, 1997). Clinical practice guidelines provide a synthesis of evidence with recommendations for informing clinical practice (Brouwers, Stacey, & O'Connor, 2010). In the National Guideline Clearinghouse, there are many guidelines focused on cancer symptom management. However, symptom guidelines were not being used by nurses providing telephone‐based support and available telephone symptom protocols were outdated (Macartney, Stacey, Carley, & Harrison, 2012; Stacey, Bakker, Green, Zanchetta, & Conlon, 2007).

Effective cancer symptom management by nurses has been shown to decrease symptom severity, improve quality of life, and lower health service use (Howell, Fitch, & Caldwell, 2002; Molassiotis et al., 2009). In some situations, symptoms can be managed through telephone‐based nursing services; however, others may be life‐threatening requiring immediate care. A systematic review identified common symptoms in emergency visits for patients with cancer (e.g., fever, pain, shortness of breath), with over half being admitted to the hospital and some having died (Vandyk, Harrison, Macartney, Ross‐White, & Stacey, 2012). Previous research on telephone‐based cancer symptom management has focused primarily on outreach calls by nurses for patients with specific cancers and there is no known evidence on guideline use for patient‐initiated calls (Beaver et al., 2009, 2012).

A team of researchers and oncology nurses with representatives from eight provinces developed the Pan‐Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support (COSTaRS) protocols for 13 common cancer treatment‐related symptoms (Stacey et al., 2013). The protocols were informed by a systematic review to identify clinical practice guidelines, formatted to be user‐friendly, and used plain language to facilitate patient communication. The protocols were endorsed by the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology and disseminated online (http://www.cano‐acio.ca/triage‐remote‐protocols). However, passive dissemination of evidence in the form of guidelines or as was embedded in the COSTaRS protocols is unlikely to result in uptake into nursing practice (Grimshaw, Eccles, Lavis, Hill, & Squires, 2012; Thompson, Estabrooks, Scott‐Findlay, Moore, & Wallin, 2007).

PURPOSE

This study aimed to build an effective and sustainable approach for implementing the COSTaRS protocols for nurses providing telephone‐based symptom support to cancer patients using a series of case studies. The specific objectives were to: (a) assess barriers influencing nurses’ use and sustained use of COSTaRS protocols, (b) monitor their use (primary outcome) after implementing interventions to overcoming modifiable barriers, and (c) compare findings across case to identify successful approaches for implementation.

METHODS

Design

The Knowledge to Action Framework (K2AF) was used to guide the tailoring and multifaceted implementation strategies and facilitate uptake of the protocols (Graham et al., 2006) and was used to analyze and synthesize similarities and differences and identify patterns across the implementation sites (cases) following an in‐depth analysis of each case. A “case” was defined by location of the setting (e.g., one of three participating ambulatory oncology centers) and time (from baseline assessment to 6 months postimplementation). Comparative case study design was selected for several reasons. According to Yin (2013), case study methodology is preferred in studies investigating “how” or “why” questions, when investigators have little control over events, and when the focus is on a contemporary phenomenon within some real‐life context. This holds true for this study; rather than being prescriptive as to how the symptom protocols should be implemented, investigators consulted with local advisory team members and each case was followed to determine how the implementation process occurred naturally. Multiple sources of quantitative and qualitative data were collected within real‐life context for each case to facilitate individual and cross‐case comparisons. Research methods for this study are described herein; for additional information, the full study protocol is published (COSTaRS, 2015; Stacey et al., 2012). The Ottawa Health Science Network Research Ethics Board (REB; 20120388‐01H), University of Ottawa REB (A 07‐12‐02), and REB's at case sites approved the study.

Framework

The K2AF has two key concepts: Knowledge Creation and the Action Cycle (Graham et al., 2006). Knowledge Creation is described as a funnel leading to more tailored knowledge. Knowledge tools at the point of the funnel are based on synthesized knowledge from systematic reviews of individual studies. The COSTaRS protocols are knowledge tools based on a synthesis of evidence reported in clinical practice guidelines (Stacey et al., 2013). The K2AF Action Cycle is a series of seven steps (Table 1). In Step 1: The knowledge users (KUs) identified the problem as oncology nurses not using evidence to guide their telephone‐based nursing practice and the COSTaRS protocols as knowledge tools presenting the best available evidence using a format sensitive to how nurses think and what nurses do. The subsequent steps in the K2AF Action Cycle are: Step 2: Adapt the knowledge tool to local context; Step 3: Assess barriers and facilitators to knowledge tool use; Step 4: Select, tailor, and implement interventions to overcome known barriers; Step 5: Monitor knowledge tool use; Step 6: Evaluate outcomes; and Step 7: Assess sustained use of knowledge tools. The study procedures were mapped onto these steps in the K2AF Action Cycle with Steps 2 and 3 in reverse order.

Table 1.

Data Sources Collected by Case Using the Knowledge to Action Framework

| Action Cycle | Data Source | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Identify the problem | Local KU team | √ | √ | √ |

| Step 2: Assess barriers/facilitators to using COSTaRS | Interviews or focus groups | 16 nurses/managers 4 patients/family | 8 nurses/managers 8 patients/family | 10 nurses/managers 3 patients/family |

| Barriers survey with nurses and managers | 31/44 (70%) | 28/50 (56%) | 19/73 (26%) | |

| Step 3: Adapt COSTaRS to the local context | Local KU team Data from step 2 | √ | √ | √ |

| Step 4: Select/tailor interventions and implement COSTaRS | Local KU team Data from step 2 | √ | √ | √ |

| Training workshop survey | 29/30 (96.7%) | 41/42 (97.6%) | 20/35 (48.8%) | |

| Step 5: Monitor use of COSTaRS | Chart audit eligible symptom telephone calls | 77/100 (77%) | 19/81 (23.5%) | 89/118 (75.4%) |

| Repeat barriers survey | 11/29 (38%) | 14 nurses | 7/31 (23%) | |

| Step 6: Evaluate outcomes | None | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Step 7: Assess sustained use of COSTaRS | Repeat barriers survey | 11 nurses | 14 nurses | 7 nurses |

| Repeat focus group | 9 nurses | n/a | n/a | |

COSTaRS = pan‐Canadian oncology symptom triage and remote support protocols; KU = knowledge users; n/a = not applicable.

Setting and Participants

The study was conducted in three ambulatory oncology programs where nurses provide telephone‐based support. In addition, these programs had established relationships between KUs and members of the COSTaRS Steering Committee. The oncology programs were purposely chosen from three provinces having different health systems and various characteristics such as urban or rural locations (Table 2). Three programs were selected to create three cases for comparing implementation in each case and across cases.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics by Case

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setting:Main oncology program | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Satellite clinic(s) | 1 | 0 | 14 |

| Nurses who provide remote support (N) | 31 | 47 | 41a |

| Nurse telephone support regular daytime hours only | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Primary nurse model | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Patients call: Central phone line | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Nurse directly | ✓ | ||

| Documentation: Paper‐based | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Electronic | In planning | ||

| Documentation format: Narrative only | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Standardized form | ✓ | ||

| Frequency of documentation: None | 7% | 4% | 11% |

| As necessary | 17% | 4% | 44% |

| Routinely | 76% | 92% | 44% |

| Documentation filed into health record as | Paper | NCR | Paper |

| Protocol use for triaging symptom calls | 3% | 50% | 39% |

| Formal training program to use symptom protocols | ✓ |

aDoes not include >30 nurses across 14 satellite clinics.

NCR = noncarbon copy paper.

An integrated knowledge translation approach was used (Bowen & Graham, 2013); whereby researchers collaborated with KUs on local advisory teams at each site. As part of their role, KUs helped facilitate data collection, discussed and reached consensus on adaptations to the COSTaRS protocols, selected interventions, and helped interpret and disseminate the findings (Abdullah & Stacey, 2014). A staff nurse was hired for 1 day per week for 1 year as the knowledge broker (KB). This role was to facilitate the study by increasing awareness, collecting data, coordinating training, and managing issues. Using committees and facilitation has been shown to enhance uptake of evidence into nursing practice (Dogherty, Harrison, & Graham, 2010; Thompson et al., 2007).

Participants within the three settings included: (a) nurses who provided telephone‐based symptom management; (b) managers, educators, and advanced practice nurses who support their role; and (c) patients and family members who have used the telephone‐based services. All participants had to speak English or French and be able to provide informed consent.

Data Collection

Multiple sources of data were collected in steps mapped onto the K2AF Action Cycle (Table 1). In step 2, current practice and baseline barriers influencing nurses’ use of COSTaRS protocols were assessed using interviews, focus groups, and a barriers survey. In step 3, findings from baseline data were discussed with local KU Teams and used to adapt the COSTaRS protocols for local use, ensuring fidelity of the content. In step 4, implementation interventions were selected to overcome identified barriers and were based on effective interventions for changing practice (Grimshaw et al., 2012; Stacey et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2007). In step 5, protocol use was monitored using a retrospective chart audit of nursing documentation and informal interactions between KU team members and nurses. Charts were audited for 100 calls from patients experiencing cancer treatment‐related symptoms within 6 months posttraining for all three cases. For case 2, 100 calls were randomly selected. For cases 1 and 3, random selection was not feasible and instead charts for the first 100 symptom calls logged by clerical staff were audited.

In step 7, factors influencing sustained use were assessed using the repeat barriers survey. In case 1 only, a repeat focus group was conducted postimplementation, as requested by their KU team.

At each step in the study, findings were discussed with local KU teams and communicated to nurses. An end of grant meeting was held with researchers and KUs. Each of the three KU teams presented their experiences with implementing the COSTaRS protocols. Meeting participants compared findings across cases and identified implications.

Measurement Tools

Measurement tools are available on our research Website www.ktcanada.ohri.ca/costars/. The barriers survey included 34 statements that ranged on a 5‐point scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree), 10 multiple choice, and 4 open questions (Stacey, Carley, et al. 2015). Open‐ended questions were: (a) barriers interfering with using symptom protocols for telephone practice, (b) factors that would make it easier to use them, (c) changes to make them more relevant to your oncology program, and (d) other comments or suggestions. Survey statements, organized into five constructs (e.g., protocol development, protocol content, use of protocols, knowledge/skills/confidence using protocols, implementation) had good to excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's α by constructs.89, .93, .81, .80, .85).

Training workshops were evaluated for acceptability and used a retrospective pre‐ and postdesign to evaluate change in nurses’ confidence with providing symptom support and using the COSTaRS protocols (Stacey, Skrutkowski, et al., 2015). The workshop satisfaction survey had 12 multiple choice questions plus two questions measuring perceived confidence at baseline and postworkshop on a 5‐point scale of strongly agree to strongly disagree (Cronbach α = .75).

Chart audit tool was created for this study to measure patients’ characteristics, type of symptom, nurses’ documentation of remote support provided (e.g., assessment, triage, medication review, self‐care strategy selection), and agreed upon plan.

Analysis

Objective 1 was to identify barriers and facilitators to using and sustained use of COSTaRS. Survey items were analyzed using univariate descriptive statistics to identify barriers and facilitators categorized according to the Ottawa Model of Research Use (Logan & Graham, 1998). Open‐ended barriers survey questions were analyzed using thematic analysis and triangulated with data from interviews and focus groups. Confidence with providing symptom support with or without COSTaRS protocols was analyzed by comparing differences pre‐ and postworkshop using Kruskal‐Wallis one‐way analysis of variance.

Each case was analyzed in depth and then comparisons were made across cases. Objective 2, use of COSTaRS protocols, was the primary outcome. It was analyzed using prevalence, calculated by dividing the number of times a protocol was used for a symptom call by the total number of symptom calls audited.

Objective 3 was accomplished by in‐depth analysis of qualitative and quantitative findings for each case and then comparing findings across cases to identify patterns in results and effective approaches for implementation.

Analysis of quantitative data was conducted using IBM SPSS Version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Qualitative data from interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim and analyzed thematically by two researchers independently to identify barriers and facilitators influencing symptom protocol use. Memos of decisions and code manuals with definitions were maintained for auditing. Findings across data sources were triangulated using thematic analysis.

RESULTS

The study was conducted from January 2013 to October 2014. Cases were from oncology programs in three Canadian provinces: one each in Eastern Canada, Quebec, and Ontario (Table 2). Findings from data collected in the study by case are reported in Tables 3 to 5. The following provides a brief summary of findings for each of the three cases and then a comparison across cases.

Table 3.

Summary of Findings by Case

| Action Cycle | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local advisory | KU advisory team | ‐Manager | ‐Manager | ‐Manager |

| ‐Educator | ‐Educator | ‐Nurse specialist | ||

| ‐Outreach liaison | ‐Staff nurse (KB) | ‐Outreach liaison | ||

| ‐Staff nurse (KB) | ‐Staff nurse (KB) | |||

| Step 1: problem | Nurse use of any protocols for symptom calls | 3.4% | 50% (Trained on using other protocols) | 39% |

| Step 2: barriers/facilitators | Protocols positively rated on content/format | >87% | >78% | >68% |

| (Table 4) | Too complex | 16% | 19% | 26% |

| Need training | 80% | 64% | 74% | |

| Step 3: adaptations | Format for health record | ✓ | ✓ | |

| (Table 4) | More comment space | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Add institutional logo | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Add call date/time | ✓ | |||

| Add space for physician signature | ✓ | |||

| Create pocket guides | ✓ | |||

| Step 4: implement | Of 13 protocols | 12 implemented | 13 implemented | 7 implemented |

| Interventions to address barriers (Table 4) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Nurses trained | 30/31 (97%) | 42/47 (90%) | 35/41 (85%) | |

| More confident using | 2.78 to 3.93/5.0 | 3.23 to 4.10/5.0 | 2.61 to 3.94/5.0 | |

| COSTaRs (pre/post) | p < .01 | p < .01 | p < .01 | |

| Step 5: monitor use | Evidence of protocols use in documentation | 36/77 (46.8%) | 2/19 (10.5%) | 28/89 (31.5%) |

| Self‐reported protocol use (barriers survey) | 9/11 (81.8%) | 11/14 (78.6%) | 4/6 (66.7%) | |

| Step 7: sustained | Integrated in orientation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| use | Easy access (e.g., filing at phone, pocket guides, electronic) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ongoing leadership support | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Use improved with practice | ✓(focus group) |

KB = knowledge broker.

Table 5.

Chart Audit Findings from Patients’ Health Recordsa

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 100 | N = 81 | N = 113 | ||

| Calls eligible | Yes | 77 (77.0) | 19 (23.5) | 89 (75.4) |

| Reason for exclusion | Not relevant to treatment | 18 (78.3) | 5 (8.1) | 17 (58.6) |

| No call documentation found | 4 (17.4) | 45 (72.6) | ||

| Did not speak with patient | 1 (4.3) | 6 (20.7) | ||

| Patient seen later in person | 5 (17.2) | |||

| Issue resolved before return call | 1 (3.4) | |||

| Current chart not provided | 7 (11.3) | |||

| No symptom protocol (e.g., pain) | 5 (8.1) | |||

| Characteristics of callers | n = 77 | n = 19 | n = 89 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Female patients | 51 (66.2) | 13 (72.2) | 54 (60.7) | |

| Age | <50 | 12 (15.6) | 3 (15.8) | 7 (8.0) |

| ≥50 to <60 | 13 (16.9) | 7 (36.8) | 25 (28.7) | |

| ≥60 to <70 | 27 (35.1) | 3 (15.8) | 31 (35.6) | |

| ≥70 | 25 (32.5) | 6 (31.6) | 24 (27.6) | |

| Current treatment | Chemotherapy | 46 (61.3) | 17 (89.5) | 59 (66.3) |

| Radiation therapy | 9 (12.0) | 1 (5.3) | 28 (31.5) | |

| Chemotherapy and radiation | 8 (10.7) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (2.2) | |

| Otherb | 12 (16.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Characteristics of symptoms | n = 77 | n = 19 | n = 89 | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Number of | One | 76 (98.7) | 14 (73.7) | 81 (91.0) |

| symptoms documented | Two or more | 1 (1.3) | 5 (26.3) | 8 (9.0) |

| Common types | Nausea/vomiting | 27% | 26% | 43% |

| of symptom | Diarrhea | 16% | 16% | 19% |

| Fatigue | 9% | 21% | 12% | |

| Mouth sores | 8% | 16% | 6% | |

| Constipation | 8% | 11% | 9% | |

| Breathlessness | 7% | 16% | 9% | |

| Skin reactions | – | 11% | 12% | |

| Protocol used | 36 (46.8) | – | 28 (31.5) | |

| Protocol referenced on telephone form | 2 (10.5) | |||

| Completed protocol | 1. Assess symptom severity | 30 (83.3) | n/a | 28 (100.0) |

| sections | 2. Triage to highest severity | 25 (69.4) | n/a | 19 (67.9) |

| 3. Review medications | 25 (69.4) | n/a | 22 (78.6) | |

| 4. Discuss self‐care strategies | 32 (88.9) | n/a | 17 (60.7) | |

| 5. Summarize and document plan | 28 (77.8) | n/a | 10 (35.7) | |

Notes. aValues are frequency (%). Frequencies may not always equal 100% due to missing data.

bOther treatments included: hormone therapy, bisphosphonate, EGFR inhibitor, tyrosine kinase inhibitor, blood transfusion, IgG.

n/a = information not available.

Case 1: Mixed Urban and Rural

For case 1, there was one main oncology program and one rural satellite clinic (Table 2). Patients leave messages with a clerk during regular office hours or voicemail after hours. In steps 1 and 2, baseline findings revealed that 3.4% nurses used protocols and several barriers (Table 3). In step 3, adaptations to the protocols were primarily focused on fulfilling requirements for filing on the patients’ health record (e.g., removed colors to comply with black and white scanning and added barcodes, patient identification area, institutional logo) and revising the process (e.g., clerks attached appropriate COSTaRS protocol(s) to the telephone message, nurses documented on the protocol(s), completed protocols were filed on the patients’ health record).

Step 4 started in January 2014 with training and other interventions to overcome barriers (Table 4). Twelve protocols were implemented; skin reaction protocol was not used given a local protocol in development. In step 5, 47% documented telephone calls had evidence of protocol use and 82% nurses reported using them (Table 3 & 5). In Step 7, nurses suggested sustained use of protocols could be facilitated by improved access, clerks clarifying patients’ symptoms to attach the correct protocol, and clear leadership direction to use them. Some nurses in the final focus group reported that as they became more familiar with the content they were able to integrate protocols into their practice. To sustain use, nurses were given pocket guide versions and protocols are used in new staff orientation.

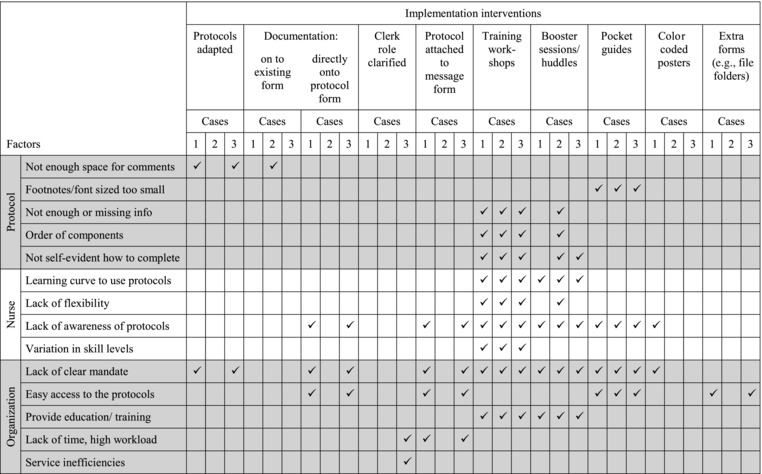

Table 4.

Interventions Mapped On To Perceived Barriers to Using the COSTaRS Protocols

|

Case 2: Urban Only

For Case 2, there were two main oncology programs (Table 2). Patients called the nurse directly during regular office hours and left voicemail messages after hours. Nurses had previously received training in use of protocols. In steps 1 and 2, baseline findings revealed that 50% of nurses used protocols and several barriers were identified (Table 3). In step 3, adaptations to the protocols primarily focused on providing bilingual (English and French) pocket protocols (e.g., smaller size, removed checkboxes and documentation space, added institutional logo) and changing name to “practice guides.” Protocols were not approved for filing on the health record because bilingual versions were too long.

Step 4 started in June 2013 with training and 12 booster education sessions over the following year (Table 4). All 13 protocols were implemented with nurses instructed to specify the COSTaRS protocol(s) used on their standardized form for documenting calls. In step 5, 11% documented telephone calls had evidence of protocol use and 79% nurses reported using them (Table 3). The organization reported delays filing documents into the chart. In step 7, to sustain use, protocols are used in new staff orientation.

Case 3: Urban and Multiple Rural Clinics

For case 3, there was one main oncology program and 14 satellite clinics (Table 2). Patients leave messages with a clerk during regular office hours. In steps 1 and 2, baseline findings revealed that 39% nurses used protocols and barriers identified are in Table 3. In step 3, adaptations to the protocols were fulfilling requirements for filing on the patients’ health record (similar to Case 1), trademarked medication names for frequently used, space for physician signature, and revising the process (similar to Case 1).

Step 4 started in September 2013 with training, booster training sessions, and other interventions to overcome barriers (Table 4). Seven of the 13 COSTaRS protocols were initially implemented (breathlessness, constipation, diarrhea, fatigue, mouth sores, nausea and vomiting, skin reaction) with plans to roll out the remaining six later. In step 5, 32% of documented telephone calls had evidence of protocol use and 67% nurses reported using them (Tables 3 and 5). In step 7, nurses suggested sustained use of protocols could be facilitated by training 15% nurses who missed workshops, protocols as pocket guides, adding to new nurse orientation, and having the new manager indicate her expectations that nurses use them. New staff felt better supported and appreciated access to evidence‐informed protocols to guide their telephone practice.

Case Comparisons

Similarities and differences among the cases are presented in Tables 3 to 5. Overall in all three cases, at least one person on the KU team (e.g., educator, clinical practice nurse, staff nurse as KB) provided leadership in facilitating implementation. As well, data collected in each of the steps were reviewed by the KU team to make decisions informing subsequent steps. The staff nurse in the KB role for cases 1 and 3 changed during the study because of workplace challenges and difficulty fulfilling the role.

In steps 1 and 2, baseline data revealed that less than half of nurses used any protocols and identified barriers and facilitators were similar across cases (Tables 3 and 4). The main baseline difference was that nurses in Case 2 had previously received training on using other symptom protocols. Despite this previous training, nurses in all three cases identified the need for training on using the COSTaRS protocols. Across cases in baseline focus groups, nurses, patients, and family members identified that using the protocols could improve consistencies across clinical settings (e.g., oncology programs, home care, emergency departments). As well, patient and family requested a similar resource for their own use at home.

A unique adaptation in step 3 for Case 2 was changing the term “protocols” to “practice guides.” The term protocol unintentionally communicated the need to use them precisely as written; whereas practice guide fit better with the aim of the COSTaRS protocols. COSTaRS protocols were designed to convey the best available evidence to inform nurses’ assessment, triage, and guiding patients in self‐management (Stacey et al., 2013).

In steps 3 and 4, the main difference was the degree of integration of the COSTaRS protocols into the work flow process (Table 4). In cases 1 and 3, clerks who recorded phone messages provided nurses with the relevant COSTaRS protocol(s) and completed COSTaRS protocols were filed on the patients’ health record. Whereas nurses in case 2 were instructed to indicate use of COSTaRS protocols on their standardized telephone call documentation form. Another difference between cases was that case 3 only implemented half of the protocols compared to cases 1 and 2. Training across cases was consistent; >85% targeted nurses trained and significant improvement in their confidence using COSTaRS protocols (Table 3).

In step 5, the chart audit revealed higher prevalence of documented protocol use for the cases that integrated the COSTaRS protocols into the workflow as a documentation tool (cases 1 & 3; Table 5). In case 2, nurses appreciated having pocket guides for quick reference but their use was rarely documented. There appeared to be more protocols on the health record when most protocols were implemented (Case 1) compared to half the protocols implemented (Case 3). Consistently across all three cases, nurses self‐reported higher use of the COSTaRS protocols than was documented on patients’ health records (Table 3).

In step 7, findings for supporting sustained use were similar across the three cases with nurses identifying the need for integrating into new staff orientation, making them easily accessible, and leadership support (Table 3). KU teams for all three cases reporting implementing these interventions.

DISCUSSION

Our comparative case study evaluated the implementation of COSTaRS protocols for use by nurses providing telephone‐based symptom support in three different oncology programs. Over 85% of nurses rated the protocols positively on content and format. However, 20% rated them as too complex and 73% identified the need for training. Training workshops were provided to >85% of targeted nurses who reported improved confidence with using the protocols (Stacey, Skrutkowski, et al., 2015). Protocol use as documentation tools or referenced on the standardized telephone form was evident in 11% to 47% of documented calls. Nurses were expected to continue using COSTaRS protocols at the end of the data collection period and the protocols were incorporated into new staff orientation. The COSTaRS protocols as knowledge tools (Gagliardi, Brouwers, Palda, Lemieux‐Charles, & Grimshaw, 2011) were able to be used in telephone‐based nursing practice.

Despite a rigorous process guided by the K2AF that engaged nurses throughout the implementation process, there was limited uptake of the COSTaRS protocols. Interestingly, newer nurses in one oncology program (Case 3) appreciated the quality of the protocols for guiding their interaction with patients. According to recommendations in a systematic review to determine effective interventions to increase research use by nurses (Thompson et al., 2007), our study used interventions informed by a theoretical framework. The K2AF allowed us to identify factors influencing the use of the COSTaRS protocols and select interventions to overcome identified barriers. Our findings showing evidence of COSTaRS protocols for some documented calls is similar to other trials evaluating tailored interventions that showed a 27% to 82% improvement in uptake of knowledge by healthcare professionals (Baker et al., 2010).

Monitoring and measuring nurses’ use of COSTaRS protocols and impact on patients’ symptom management was challenging. The objective data were based on the chart audit. The chart audit was feasible to conduct but nurses’ paper‐based documentation of calls was not necessarily filed on the patients’ health record. In addition, despite that nurses are expected to document all calls (CNA, 2007), previous research and our baseline assessment of barriers and facilitators showed that nurses do not necessarily document their calls (Macartney et al., 2012; Stacey, Carley, et al., 2015). Without consistent documentation of protocol use, it is difficult to know the extent of their use in telephone calls. While it was beyond the scope of this study to evaluate patient symptom severity, future studies could incorporate newer approaches to measure cancer patients’ symptom severity 24 hours a day for 7 days a week with smart phones (Breen et al., 2015). Further research could also include recording calls to audit call quality or evaluate nurses’ symptom management with simulated patients.

The KU teams facilitated the study, ensured implementation interventions were appropriate for nurses, and had an essential role in adapting the COSTaRS protocols to the local context. Previous research shows that involving KUs throughout the research process is a strong predictor that evidence‐based knowledge will be used (Bowen & Graham, 2013). Although managers were part of the KU Team, their potential role to influence successful implementation was underutilized. For example, some nurses indicated that the mandate to use the COSTaRS protocols was unclear at baseline and remained unclear at the end of the study. Subsequent research should explicitly consider the influence of leadership as part of the implementation interventions. The use of staff nurses as KBs was a new role for the nurses. In two of three cases, the nurse responsible for this role changed and subsequent use of staff nurses on the team should consider clear role expectations and preparation (Dogherty et al., 2010).

Broader implementation of the COSTaRS protocols was identified as important for providing consistent symptom management across clinical settings (Stacey, Carley, et al., 2015). In addition to expanding into other oncology programs, the COSTaRS protocols are relevant to homecare nurses, emergency room staff, nursing schools, and patients. Patients and family members requested a similar resource for their use at home which was beyond the scope of this study. The COSTaRS protocols are based on clinical practice guidelines and therefore, the evidence on symptom management is relevant across care settings. Given the need to adapt the COSTaRS protocols for each of the three settings in this study, broader implementation will likely require adaptation to other clinical contexts (Harrison, Legare, Graham, & Fervers, 2010).

There are study limitations and strengths that should be considered when interpreting the findings. There was a poor response rate to the repeat barriers survey to assess for barriers and facilitators influencing sustained use of the protocols which made it difficult to determine self‐reported use of COSTaRS protocols and remaining factors influencing sustained use. Dillman's survey methods were used with three reminders (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2014) resulting in 26% to 70% response rate at baseline and 23% to 38% at the end of the study. Reasons for poor response are unclear but next time authors would consider using a shorter survey or conduct repeat focus groups at all three programs. As well, there is likely self‐report bias in nurses’ reported use of protocols. Although there was some indication that nurses were using protocols in the chart audit, it was difficult to determine actual use as documentation appears to be a poor proxy for behavior. Protocol usability testing was planned a priori but it was not possible to initiate due to nurses’ high workload making it too difficult to remove them for additional study data collection. Finally, subsequent research should measure patient outcomes as indicated in Step 6 of the K2AF.

Strengths of the study were the case comparisons using a range of data sources, techniques used to enhance credibility of qualitative findings, and engagement of KUs as part of the research team. As well, the study focused on trying to understand how to implement the protocols within three different Canadian provincial health systems.

CONCLUSIONS

Using a systematic implementation process, this study demonstrated some increased uptake of evidence‐informed symptom management protocols in telephone‐based nursing practice. Implementation interventions were tailored to the identified barriers and included support from the local KU team. Nurses were satisfied with the training workshops and felt more confident with using the protocols and providing symptom management. There was higher evidence of their use on the health record when the symptom protocol was distributed with the telephone message and when nurses documented on it. There needs to be clear organizational alignment and ongoing support for nurses to sustain protocol use. Future research should include more rigorous measures to determine protocol use, monitor patient symptom changes, and explore patients’ experience when nurses use protocols.

LINKING EVIDENCE TO ACTION

Multifaceted implementation strategies, tailored to identified barriers, included leadership, organizational support, and local facilitation.

Training workshops increased nurses’ confidence using COSTaRS protocols.

Knowledge translation tools, formatted as protocols, guided nurses in their telephone‐based cancer symptom management.

Similar protocols would be of benefit to patients and other healthcare professionals.

Future research evaluating their use for specific clinical situations could include: (a) outgoing calls to monitor patients receiving chemotherapy; (b) focused implementation of one protocol such as nausea and vomiting (most common type of call); (c) qualitatively exploring patients’ experiences with telephone‐based nursing guidance for managing symptoms; and (d) more rigorous evaluation of patient outcomes after nurse symptom management.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the nurses, patients, and family members who participated in the focus groups, interviews, and surveys. The COSTaRS Knowledge to Action Study (2012‐2014) was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant No. KAL 122159).

WVN 2016;00:1-13

References

- Abdullah, G. , & Stacey, D. (2014). Role of oncology nurses in integrated knowledge translation. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 24(2), 63–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, R. , Camosso‐Stefinovic, J. , Gillies, C. , Shaw, E. J. , Cheater, F. , Flottorp, S. , & Robertson, N. (2010). Tailored interventions to overcome identified barriers to change: Effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 17(3), 1–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, K. , Tysver‐Robinson, D. , Campbell, M. , Twomey, M. , Williamson, S. , Hindley, A. , … Luker, K. (2009). Comparing hospital and telephone follow‐up after treatment for breast cancer: Randomised equivalence trial. British Medical Journal, 338, a3 147 Retrieved from http://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/338/bmj.a3147.full.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, K. , Campbell, M. , Williamson, S. , Procter, D. , Sheridan, J. , Heath, J. , & Susnerwala, S. (2012). An exploratory randomized controlled trial comparing telephone and hospital follow‐up after treatment for colorectal cancer. Colorectal Disease, 14(10), 1201–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, S. , & Graham, I. D. (2013). Integrated knowledge translation In Straus S. E. T., Tetroe J., & Graham I. D. (Eds.), Knowledge translation in health care: Moving from evidence to practice (pp. 14–23). Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, S. , Richie, D. , Schofield, P. , Husueh, Y. S. , Gough, K. , Santamaria, N. , … Aranda, S. (2015). The Patient Remote Intervention and Symptom Management System (PRISMS)—A telehealth‐mediated intervention enabling real‐time monitoring of chemotherapy side‐effects in patients with haematological malignancies: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 16(1), 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers, M. , Stacey, D. , & O'Connor, A. (2010). Knowledge creation: Synthesis, tools and products. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182(2), E68–E72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Nurses Association . (2007). Telehealth: The role of the nurse. Ottawa, Canada: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, A. (1997). Where do I stand? Legal implications of telephone triage. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 6(3), 227–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSTaRS (2015). The pan‐Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support (COSTaRS) Project. Retrieved from http://www.ktcanada.ohri.ca/costars/

- Dillman, D. A. , Smyth, J. D. , & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed‐mode surveys: The tailored design method (4th ed). Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dogherty, E. J. , Harrison, M. B. , & Graham, I. D. (2010). Facilitation as a role and process in achieving evidence‐based practice in nursing: A focused review of concept and meaning. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 7(2), 76–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagliardi, A. R. , Brouwers, M. C. , Palda, V. A. , Lemieux‐Charles, L. , & Grimshaw, J. M. (2011). How can we improve guideline use? A conceptual framework of implementability. Implementation Science, 6(26), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham, I. D. , Logan, J. , Harrison, M. B. , Straus, S. E. , Tetroe, J. , Caswell, W. , & Robinson, N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26, 13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw, J. M. , Eccles, M. P. , Lavis, J. N. , Hill, S. J. , & Squires, J. E. (2012). Knowledge translation of research findings. Implementation Science, 7(1), 1–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, M. B. , Legare, F. , Graham, I. D. , & Fervers, B. (2010). Adapting clinical practice guidelines to local context and assessing barriers to their use. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182(2), E78–E84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell, D. , Fitch, M. , & Caldwell, B. (2002). The impact of interlink community care nurses on the experience of living with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 29(4), 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan, J. , & Graham, I. D. (1998). Toward a comprehensive interdisciplinary model of health care research use. Science Communication, 20(2), 227–246. [Google Scholar]

- Macartney, G. , Stacey, D. , Carley, M. , & Harrison, M. B. (2012). Priorities, barriers and facilitators for remote telephone support of cancer symptoms: A survey of Canadian oncology nurses. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 22(4), 235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molassiotis, A. , Brearley, S. , Sanders, M. , Craven, O. , Wardley, A. , Farrell, C. , … Luker, K. (2009). Effectiveness of a home care nursing program in the symptom management of patients with colorectal and breast cancer receiving oral chemotherapy: A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27(36), 6191–6198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, D. , Bakker, D. , Green, E. , Zanchetta, M. , & Conlon, M. (2007). Ambulatory oncology nursing telephone services: A provincial survey. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 17(4), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, D. , Bakker, D. , Ballantyne, B. , Chapman, K. , Cumminger, J. , Green, E. , … Whynot, A. (2012). Managing symptoms during cancer treatments: evaluating the implementation of evidence‐informed remote support protocols. Implementation Science, 7(1), 110. doi:1748‐5908‐7‐110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, D. , Macartney, G. , Carley, M. , Harrison, M. B. , Pan‐Canadian Oncology, Symptom, T. , & Remote Support, G. (2013). Development and evaluation of evidence‐informed clinical nursing protocols for remote assessment, triage and support of cancer treatment‐induced symptoms. Nursing Research and Practice. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23476759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, D. , Carley, M. , Kohli, J. , Skrutkowski, M. , Avery, J. , Bazile, A. M. , … Budz, D. (2014). Remote symptom support training programs for oncology nurses in Canada: An environmental scan. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 24(2), 78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, D. , Carley, M. , Ballantyne, B. , Skrutkowski, M. , Whynot, A. , & Pan‐Canadian Oncology Symptom Triage and Remote Support (COSTaRS) Team. (2015). Perceived factors influencing nurses' use of evidence‐informed protocols for remote cancer treatment‐related symptom management: A mixed methods study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19(3):268–77. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25529936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, D. , Skrutkowski, M. , Carley, M. , Kolari, E. , Shaw, T. , & Ballantyne, B. (2015). Training oncology nurses to use remote symptom support protocols: A retrospective pre‐/post‐study. Oncology Nursing Forum, 42(2), 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D. S. , Estabrooks, C. A. , Scott‐Findlay, S. , Moore, K. , & Wallin, L. (2007). Interventions aimed at increasing research use in nursing: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 11, 2–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandyk, A. D. , Harrison, M. B. , Macartney, G. , Ross‐White, A. , & Stacey, D. (2012). Emergency department visits for symptoms experienced by oncology patients: A systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(8), 1589–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (2013). Case study research. Design and methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

Implementation of Symptom Protocols for Nurses Providing Telephone‐Based Cancer Symptom Management: A Comparative Case Study

Implementation of Symptom Protocols for Nurses Providing Telephone‐Based Cancer Symptom Management: A Comparative Case Study