Abstract

Objective

Each year, more than 11,000 adolescents and young adults (AYAs), aged 15–34, die from cancer and other life-threatening conditions. In order to facilitate the transition from curative to end-of-life (EoL) care, it is recommended that EoL discussions be routine, begin close to the time of diagnosis, and continue throughout the illness trajectory. However, due largely to discomfort with the topic of EoL and how to approach the conversation, healthcare providers have largely avoided these discussions.

Method

We conducted a two-phase study through the National Cancer Institute with AYAs living with cancer or pediatric HIV to assess AYA interest in EoL planning and to determine in which aspects of EoL planning AYAs wanted to participate. These results provided insight regarding what EoL concepts were important to AYAs, as well as preferences in terms of content, design, format, and style. The findings from this research led to the development of an age-appropriate advance care planning guide, Voicing My CHOiCES™.

Results

Voicing My CHOiCES™: An Advanced Care Planning Guide for AYA became available in November 2012. This manuscript provides guidelines on how to introduce and utilize an advance care planning guide for AYAs and discusses potential barriers.

Significance of Results

Successful use of Voicing My CHOiCES™ will depend on the comfort and skills of the healthcare provider. The present paper is intended to introduce the guide to providers who may utilize it as a resource in their practice, including physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, psychiatrists, and psychologists. We suggest guidelines on how to: incorporate EoL planning into the practice setting, identify timepoints at which a patient’s goals of care are discussed, and address how to empower the patient and incorporate the family in EoL planning. Recommendations for introducing Voicing My CHOiCES™ and on how to work through each section alongside the patient are provided.

Keywords: End of life, Palliative care, Adolescents and young adults, Advance care planning, Communication

BACKGROUND

Historically, adolescents and young adults (AYAs) have not been involved in their own end-of-life care (EoL) planning. Some care providers exclude AYAs from advanced care planning because they have been deemed not legally competent to make decisions for themselves (Hammes et al., 2005). In the literature, researchers have noted that discussions are also withheld because healthcare professionals feel uncomfortable, unprepared, and unskilled in having EoL discussions (Thompson et al., 2013; Christakis, 1999; Curtis et al., 2000; Gorman et al., 2005; Scherer et al., 2006; Yedidia, 2007). Healthcare provider discomfort has also been linked to a lack of knowledge of advance directive laws and inadequate specific training in delivering bad news (Morrison, 1998). Additionally, healthcare providers cite lack of time to invest in such planning discussions, minimal reimbursement, and strong personal emotional responses as further impediments to communicating with patients and families during EoL discussions (Legare et al., 2008; Vieder et al., 2002; Wiener & Roth, 2006).

Despite significant efforts to initiate palliative care and better integrate advance care planning for adults, a literature review by Hammes & Briggs (2011) suggested that introduction of these practices with AYAs has been met with considerable resistance by practitioners. Moreover, integration of advanced care planning documents into ongoing care and treatment requires that providers be willing to utilize them and have the resources needed to implement them.

The present paper discusses how mental health professionals can facilitate EoL care with AYAs by assisting in initiation of conversations that involve family members and engage the healthcare team. A research-initiated, developmentally based advance care planning guide document for AYAs—Voicing My CHOiCES™—became available in October 2012. For mental health professionals who choose to use Voicing My CHOiCES™, the present paper also provides specific strategies on how to introduce and utilize this document.

THE AYA POPULATION

The span of AYA development typically refers to patients aged 15 to 39 at the time of their initial cancer diagnosis (Coccia et al., 2012), leaving what is age appropriate at one end of the continuum possibly inappropriate for an AYA at the other end. Deciphering what is appropriate for each individual requires an understanding of the developmental processes involved in adolescence and young adulthood. One literature review suggested that children aged 10–20 with advanced cancer demonstrate an understanding of end-of-life discussions, consequences, and decision-making (Waldman & Wolfe, 2013). Furthermore, Garvie et al. (2013) found that half a teen population (56%) indicated that not being able to discuss EoL preferences was “a fate worse than death.” Adolescence and young adulthood is a time of developing one’s identity and asserting one’s autonomy. AYAs deserve the opportunity to prepare for, and cope with, the realities of advancing illness if they so choose (Larson & Tobin, 2000) and to be involved in end-of-life conversations. Respecting their decisions is critical to promoting both their dignity and control (Pousset et al., 2009). It is also essential for healthcare providers to recognize that having an EoL discussion is often difficult for the patient to initiate. Some AYAs may feel that talking about the end of life suggests mistrust of the current medical efforts or is an expression of loss of hope. Others may worry that talking about EoL will make it happen sooner. Family members often avoid this conversation in order to maintain a stance of support. Health professionals can empower AYAs by emphasizing that discussions surrounding EoL preferences are meant to ensure that healthcare providers respect individual choices when planning care.

INTRODUCING ADVANCED CARE PLANNING

When having EoL discussions related to advance care planning, Hammes and Briggs (2011) suggest three core components: (1) understanding, (2) reflection, and (3) discussion. This model emphasizes the importance of a patient’s understanding of why advance care planning is important, the components of the planning process, as well as the advantages of planning and consequences of not planning. A critical component is ensuring that patients understand their diagnosis, their treatment options, potential outcomes, and the chances of survival in order to make informed decisions. An essential element for the success of EoL discussions is identification of patients’ personal goals, values, and beliefs as they relate to their quality of life. Developed by two of our authors (LW and MP) in 2008, The Advance Care Planning Readiness Assessment is one way to evaluate a patient’s comfort by having an EoL conversation. This measure consists of three yes/no questions relating to the patient’s opinions of: (1) whether talking about what would happen if treatments were no longer effective would be helpful, (2) whether talking about medical care plans ahead of time would be upsetting, and (3) whether they would be comfortable writing down/discussing what would happen if treatments were no longer effective. Once this assessment is made, and readiness is confirmed, discussing EoL planning becomes the central focus of the conversation. The provider can then encourage the patient to communicate with their chosen healthcare agent, their family members, and their healthcare providers. It is talking through these three components that allow written preferences to be documented. While the Advance Care Planning Readiness Assessment evaluates potential participants’ comfort discussing EoL, it should be noted that there is a limited amount of data to support the fact that readiness to have these discussions correlates with agreement to participate in such discussions, again emphasizing the importance of assessing each patient individually.

EoL discussions could be improved if care providers developed and implemented a systematic approach consistently for all AYA patients living with a life-limiting illness (Weissman, 1998). Part of developing a systematic approach is to identify the time-points at which a patient’s wishes and goals are discussed—for example, at the time of discharge from a hospital. It is advisable to first introduce advance care planning when the patient is relatively stable and not in a state of crisis. It is also important for healthcare providers to check if an advance directive has already been considered or completed and, if not, to provide appropriate resources for the creation of legally binding documents, including a living will and a durable power of attorney for healthcare.

A recent commentary provided sample conversations that can help the provider identify a surrogate decision maker (Wiener et al., 2013), for example:

While we are hopeful that your treatment will be effective against your disease, we have learned from other families like your own that not suggesting that you give some thought to some difficult issues early on is irresponsible of us. For example, it would be great if you would communicate with each other about who would be the person to make medical decisions for you if you became very ill and not able to do so on your own.

Such conversations should be tailored to the needs of the individual AYA and family. Having conversations early on paves the way to approach subsequent discussions more smoothly, such as when the disease recurs or it is clear that the illness is becoming refractory to treatment. At later timepoints, the earlier-held conversation can be reviewed and the AYA asked if he/she still holds those same beliefs (Wiener et al., 2013).

Good communication is at the heart of advance planning discussions and should be made a priority by all involved healthcare providers. Understanding a patient’s experience and concerns may help the provider relate better to the patient’s treatment choices (Emanuel et al., 2004). It is important to remember that advance care planning programs succeed: (1) when they focus on the communication strategies necessary to assist individuals in making informed healthcare decisions rather than on simple completion of a document, and (2) when advance care planning is an ongoing part of the process of patient care embedded within a healthcare delivery system (Prendergast, 2001; Wenger et al., 2008).

INTRODUCING VOICING MY CHOICES™

Discussing EoL with AYAs is challenging, not only because of the sensitive nature of the issue but also because of the need for a developmentally appropriate approach and language. Voicing My CHOiCES™ is an advance care planning guide designed to assist young people living with a serious illness in communicating their EoL preferences to their family, care-givers, and friends.

The initial page of Voicing My CHOiCES™ provides a brief overview of the purpose of the document. It offers comfort and purpose to AYAs who may have mixed feelings about utilizing a guide, informs AYAs that document completion is based on their thoughts and desires, and illustrates autonomy and respect for their ability to make decisions about their own care. The introduction also indicates that the AYA can choose to fill out the document in its entirety or to whatever extent they feel comfortable. Additionally, AYAs are encouraged to utilize the support of available healthcare providers, as many concepts or terms may be difficult to understand or think about.

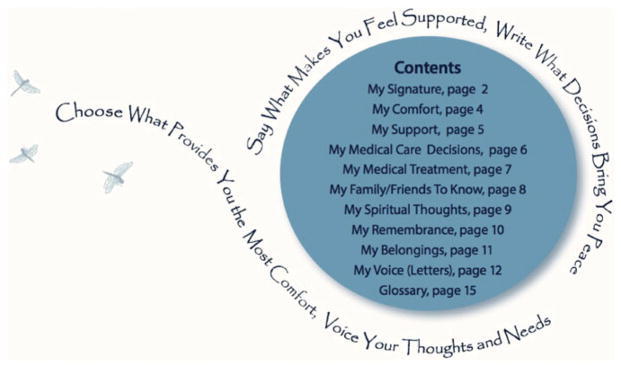

Following the introductory pages are the nine sections that comprise Voicing My CHOiCES™ (see Figure 1). It is recommended that each section within the document be presented as a separate “module,” tailored to AYAs’ concerns at the time. For many, this approach may entail starting with thoughts about the provision of comfort or support, located on pages 4–5, as these are often perceived as less stressful than direct EoL decision making (Wiener et al., 2008). Some healthcare providers may opt to allow the AYA to work independently on completing these less-stressful modules; however, working together can provide an opportunity to establish rapport and to gently introduce EoL and elicit preferences. Moreover, this relationship may facilitate an easier transition to the more serious modules. It is highly recommended that the AYA work alongside a health-care provider when making decisions about life-support treatments. While Voicing My CHOiCES™ includes a glossary to help clarify confusing or complicated medical terminology, some of these items can be difficult to understand, especially in the context of cure versus extension of life. It is very important to remind the AYA that the document can and should be reviewed and revised if health needs due to medical status and support systems change over time. Wiener and colleagues (2013) suggested that healthcare providers engage the patient using the following sample conversation:

Although we are hoping that this next treatment [medicine] will be helpful, many people your age have told us that they found it helpful to have a say about what they would want or not want if treatment doesn’t go as expected. In fact, people your age helped create a guide so that they could put down on paper the things that are important to them.

Fig. 1.

Voicing My CHOiCES™ table of contents.

HOW I WOULD LIKE TO BE SUPPORTED SO I DON’T FEEL ALONE

Developmentally, AYAs place significant emphasis on the importance of both familial and peer relationships and have an expressed need for intimacy. Erikson (1950) described this stage as a time when youth begin to seek companionship and love. They explore their relationships with others, leading toward longer-term commitments with people outside their family. Inability to form or maintain these relationships can result in feelings of isolation or depression. Given that the need to maintain interpersonal relationships is critical to the AYA population, this section of the document addresses the individual’s capacity for independent decision making in a developmentally appropriate way by allowing AYAs to specify their preferences on visitation, as well as who they want with them. Healthcare providers working alongside AYAs completing Voicing My CHOiCES™ should reiterate that their support needs are critically important. Sample introductory statements for each section of Voicing My CHOiCES™ can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

How to introduce sections of Voicing My CHOiCES™

| Document Section | Sample Statements to Start Conversations |

|---|---|

| Introduction | “Although we are hoping that this next treatment [medicine] will be helpful, many people your age have told us that they found it helpful to have a say about what they would want or not want if treatment doesn’t go as expected. In fact, people your age helped create a guide so that they could put down on paper things that are important to.” |

| How I would like to be supported so I don’t feel alone | “Some AYAs say they can feel alone, even when they are in a room with a lot of people. Have you ever felt this way?” |

| ”When you are not feeling well, and need some support, who do you like to have with you?” | |

| ”When you are asleep, is there someone you prefer to have near you?” | |

| How I want to be comforted | “When you don’t feel well, what tends to bring you the most comfort? Do you like the room dark? Do you tend to want to listen to music?” |

| ”When you don’t feel well are there certain clothes that are most comforting to you?” | |

| ”This is a page where you can share what YOU find most comforting so that others can know without you having to tell them.” | |

| Who I want to make my medical care decisions if I cannot make them on my own | “How does decision making for your medical needs happen now? Are you comfortable with the way decisions are currently made?” |

| ”Has it ever been hard to voice your opinion?” | |

| ”Has it ever happened to you where you couldn’t make a decision and someone made it for you?” | |

| ”Have you ever given thought to who you would trust most to make decisions for you, if you ever become unable to make them yourself?” | |

| ”Do you know who your mom or dad has chosen to make decisions for them?” | |

| ”Here you can put down who you would be most comfortable making medical decisions if you were not able to. Feel free to put more than one person or to ask for the people you choose to work together.” | |

| The types of life-support treatments I want, or do not want | “Many AYAs have told us that there was a specific test(s) that they really dislike—or find especially annoying, and if they could avoid these, they would. Have you had a specific test or experience you hope to never have to experience again?” |

| ”Others have thought a lot about whether or not they would ever want to have aggressive interventions, like being on a breathing machine, if their condition was not reversible. Have you ever thought about something like this?” | |

| ”While your care team will always provide every medicine possible to help you and do everything they can to support you, here you can share any thoughts that you might have about how much mechanical support [support by machines] you might like provided if, for example, your body was not able to work on its own.” | |

| What I would like my friends and family to know about me | “Many people your age have told us that they tend to worry more about other family members sometimes than they worry about what is happening to themselves. Has this ever been the case for you?” |

| ”Is there anyone in your family who is having a really hard time? What worries you most about that person? How does your family act when there is a crisis with your health or with someone else in the family? What would make you feel better knowing would happen if you were no longer here?” | |

| ”What about your friends? Is there anyone you worry about most? Many people your age also tell us that there are certain things that they have just not known how to say to people who are important to them. Like something a friend might have done that was especially cool or meaningful. Here is a chance to tell them something that was appreciated or to apologize for something that you wish you hadn’t said. Or to maybe give forgiveness to someone who hurt you badly. It also allows you to share things that are awfully hard to express in person.” | |

| Spiritual thoughts and wishes | “Some AYAs find great comfort in their spiritual beliefs or traditions in their faith or religion. Do you?” |

| ”Here is a place where you can share what you find most comforting to you. There are no right or wrong ways to be spiritually or emotionally comforted!” | |

| How I wish to be remembered | “Almost all of us think about what would happen to us if we died. Most of us have played out our funeral in our minds—who we would want or not want there, what we would want people to say. There is nothing crazy about thinking about this.” |

| ”Here, you have an opportunity to make sure that your thoughts are heard.” | |

| ”What is most important to you? Do you want there to be a service? If so, what kind? Certain people you would want to be there? Do you have favorite hymns or music that are especially meaningful to you or even food or drinks that you love and would like to be included?” | |

| ”Many AYAs have shared that they wanted something positive to come from their suffering—for example, for doctors to learn from their tumor or cells how to help others who have the same disease as they have. Do you have similar thoughts as these? Most importantly, AYAs have shared that they never want to be forgotten. While those who love you will never forget you for all of their living days, there are ways you can help them feel like they are still doing things for you after you are gone. For example, how you might like to be remembered?” | |

| My voice | “Some AYAs have found completing this page(s) alone to be enough to bring them a sense of emotional closure or peace. But even knowing how to start this page can be really difficult. If you were to want to leave a letter or a message to someone, or some people in your life, who would this be?” [Write a list.] “Who would be the hardest person to write to?” [Create an order.] |

| ”I can ask you some questions and then write down your thoughts. Would you like to try and see how this feels? We can start with [the least difficult person to write to]. [If yes.] “How about something like:” | |

| ”Writing this letter to you is really hard to do,” or “I am so sorry that I am here writing this letter to you.” | |

| ”You have been so important to me because …” | |

| ”I will especially always remember …” | |

| ”One thing I want you always to know …” | |

| ”In the future, if you ever get very sad …” |

HOW I WANT TO BE COMFORTED

Adolescence and early adulthood are when young people are trying to formulate their self-identity and answer the question of “Who am I?” Erikson (1950) noted that this stage is the first point in one’s development based primarily on what a person does or achieves. The adolescent is in a period of trying to discover and find his/her own identity while negotiating social interactions and “fitting in.” This section of the document allows for personalization of the EoL experience and role preservation by allowing AYAs to specify their favorite foods, readings, and music that bring them comfort. AYAs are also provided the opportunity to document the extent to which pain medication or other potentially sedating medications are utilized by determining how alert they want to remain during treatment. Additionally, the Dignity Model (Chochinov, 2006) emphasizes the importance of respecting and preserving the individual’s dignity, suggesting that individuals who feel that their dignity is impacted are more likely to have psychological and symptom distress (Chochinov et al., 2002). Healthcare providers should therefore emphasize that while undergoing treatment AYAs should maintain their dignity and have their individual wishes respected. For example, some AYAs may prefer to be able to engage with family and friends and tolerate some pain rather than being overly sedated due to pain medications. With completion of this section, AYAs can inform family members and healthcare providers how they wish to be comforted throughout the care continuum.

WHO I WANT TO MAKE MEDICAL CARE DECISIONS IF I CANNOT MAKE THEM ON MY OWN

AYAs have indicated that having to choose only one healthcare agent is difficult (Wiener et al., 2012), and for this reason there is extra space for more than one agent to be designated. Having the option for multiple persons to be involved in care decisions maintains the AYA’s autonomy for decision making, as does their ability to specify what type of decisions healthcare agents should make for them. Specifically, AYAs can indicate here whether they would want their healthcare agent(s) to arrange for hospital discharge and take them home, if that is their wish. Healthcare providers who are working alongside the AYA when completing this document should emphasize the importance and significance of expressing their wishes directly to the person(s) they designate as their healthcare agents. Health professionals specifically can help with facilitating this conversation in various ways, such as offering to be present when the AYA has potentially difficult conversations with their chosen healthcare agents.

THE TYPES OF LIFE SUPPORT TREATMENTS I WANT, OR DO NOT WANT

Many AYAs with chronic illness struggle with loss of control, especially with regard to the medical care they receive. AYAs often consider the potential impact of their death on others when considering treatment options (Waldman & Wolfe, 2013). This consideration has the potential to lead them to undergo treatment in an attempt to satisfy their families/friends when they would rather forego treatment and enjoy a better quality of life at home. By providing AYAs with the ability to choose which life-support treatments they do or do not want, and under what circumstances, Voicing My CHOiCES™ allows individuals to maintain control in deciding how much they want to endure, while still allowing them to preserve their hope in instances where they feel life-support treatments are worth attempting. As many of these items are very complex and difficult to understand, Voicing My CHOiCES™ suggests completing this page alongside a healthcare provider who can explain terms and circumstances and/or answer any questions. Healthcare providers who review this portion of the document with the AYA should be clear in explaining the circumstances under which life-support treatments are curative versus when they are provided only to extend life. These decisions are difficult for any population, especially AYAs. Reminders that, if desired, decisions can be changed in the future can be a source of comfort and empowerment.

WHAT I WOULD LIKE MY FRIENDS AND FAMILY TO KNOWABOUT ME

The growth of personal relationships—with both friends and family—is a critical component of AYA development. Many AYAs with chronic illness have struggled with maintaining peer relationships over the course of their illness and through different treatment periods. Some may have had extended school absences that limited peer interaction. Others have cherished meaningful friendships throughout the disease trajectory. In this section of Voicing My CHOiCES™, the AYA can express the importance of these relationships. By providing these words and sentiments, one’s identity can remain intact in spite of advancing illness and even after they are gone. These words can also potentially ease worries regarding how friends and family will maintain memories of them and cope with their loss. Moreover, AYA self-worth is given permanence and legacy when they are allowed to communicate the things they want others to know about them.

MY SPIRITUAL THOUGHTS AND WISHES

Later adolescence and early adulthood is a period often marked by more macro-level identity exploration. Specifically, many AYAs become more attached to cultural, spiritual, and community organizations as they search to find out who they are. In the context of chronic illness, many individuals turn to their faith or spiritual connections as a means of coping. While many individuals find spiritual resources, such as hospital clergy members, to be helpful supports, others may not find comfort in these options or may only want to engage upon request. This section of Voicing My CHOiCES™ allows individuals to specify whether or not they want spiritual support incorporated into their care. It also allows AYAs to designate the type and frequency of support and other methods of spiritual care where they find comfort, which may differ from their family’s beliefs. While medical providers are often encouraged to keep personal spiritual or religious beliefs private, it is important to communicate that the AYA’s faith and spiritual needs will be respected and integrated as best as possible.

HOW I WISH TO BE REMEMBERED

AYAs faced with a life-threatening illness are often preoccupied with thoughts associated with how they would want to be remembered if they were to die from their disease (Wiener, 2008; Lyon et al., 2004; Hinds et al., 2003; McAiley et al., 2000). Providing a chance for them to share thoughts about how they wish to be thought of and remembered in the future allows AYAs to create a permanent record of their words and feelings, which in turn provides their loved ones with information that is meaningful to honor and/or preserve. Some AYAs prefer to be a part of planning their funeral and/or memorial service in order to lessen the amount of uncertainty as to how they will be remembered after death or how their remains will be handled. This section of Voicing My CHOiCES™ allows AYAs to specify what type of service they would like, if they prefer burial or cremation, open or closed casket, and whether or not they would like an autopsy or donate their cells/tissues to science. Open-ended questions are also provided so that AYAs can specify more details about the aforementioned if desired, including, for example, what clothes they would like to be wearing, items they want with them, the food/music/readings they would prefer at their service, and what charities or organizations they may like supported in their memory.

By designating how their belongings are to be distributed and who can go through their personal possessions, the second portion of this section allows AYAs to maintain autonomy and some amount of control. This section also offers AYAs an opportunity to describe how they would like to be remembered on special days, including their birthday and personally significant holidays.

MY VOICE

An important part of EoL discussions is to provide an opportunity for the AYA to say certain things to the people they love (Larson & Tobin, 2000). This may include leaving notes or letters to loved ones. The final pages of Voicing My CHOiCES™ are designated for AYAs to communicate last wishes, share fond memories, or speak about how they will exist beyond death. Such legacy letters allow AYAs to create something meaningful and lasting beyond death. Some may find this activity overwhelming despite their desire to complete it. Mental health professionals can be of great assistance in helping AYAs organize and write these letters while providing support in dealing with their emotional needs during the process.

GLOSSARY

Due to the complicated nature of many concepts and medical procedures described in an advance care planning guide, Voicing My CHOiCES™ includes a glossary to further clarify these terms for AYAs. Healthcare providers should emphasize that, even with the additional explanation provided in the guide, they are available to clarify concepts within the guide and answer any additional questions, particularly those regarding terms related to life-support measures.

DISCUSSION

In summary, adolescents and young adults want to discuss EoL issues with the healthcare providers they trust and who have been honest with them from the inception of care. Healthcare providers must delicately balance the need to respect and maintain hope while promoting meaningful conversations throughout the illness trajectory, including when death approaches. These conversations can be complicated with AYAs who are dealing with cognitive, emotional, physical, and social transitions across a wide spectrum of family and cultural backgrounds. By opening difficult conversations compassionately and being able to document thoughts about EoL and remembrance concerns, AYAs have the opportunity to give meaning to their life and their family’s emotional needs after their death. Voicing My CHOiCES™ was designed to be a place for AYAs to “Say what makes you feel supported. Write what decisions bring you peace. Choose what provides you most comfort. Voice your thoughts and needs.” Accordingly, it can potentially be a “blueprint” and/or legacy document that reaffirms their child’s self-worth and fulfills their final wishes.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

While Voicing My CHOiCES™ was designed based on the feedback of adolescents and young adults, the final document has not been evaluated for use. Likewise, to date, no research has been conducted on how to include the AYA’s family or surrogate decision maker into the discussion. Given that family plays a critical role in following through with an AYA’s EoL preference, further research is needed to determine whether document completion enhances communication between the AYA and their friends/family members. Voicing My CHOiCES™ was never intended to be a document to be handed out and completed by the AYA on his or her own. It was envisioned as a tool to open communications with adolescents and young adults and, therefore, not written with the intention of being legally binding. Thus, further research should investigate how to approach this issue with AYAs under the age of 18 who may wish to have their preferences become legally binding.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Institutes of Health, the Pediatric Oncology Branch, the National Cancer Institute, the Center for Cancer Research, and the National Institute of Mental Health. Voicing My CHOiCES ™ was developed by the authors within the National Institute of Cancer and the National Institute of Mental Health, with the very appreciated assistance of Kathleen Samiy, Haven Battles, Ph.D, Elizabeth Ballard, Ph.D., and Melinda Merchant, M.D.

References

- Christakis NA. Death foretold: Prophecy and prognosis in medical care. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov HM. Dying, dignity, and new horizons in palliative end-of-life care. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2006;56(2):84–103. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.2.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity in the terminally ill: A cross-sectional, cohort study. Lancet. 2002;360(9350):2026–2030. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)12022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccia PF, Altman J, Bhatia S, et al. Adolescent and young adult oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2012;10(9):1112–1150. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Caldwell ES, et al. Why don’t patients and physicians talk about end-of-life care? Barriers to communication for patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and their primary care clinicians. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(11):1690–1696. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.11.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Wolfe P, et al. Talking with terminally ill patients and their caregivers about death, dying, and bereavement. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164:1999–2004. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.18.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York: W.W. Norton; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman TE, Ahern SP, Wiseman J, et al. Residents’ end-of-life decision making with adult hospitalized patients: A review of the literature. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2005;80(7):622–633. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200507000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammes BJ, Briggs L. Respecting Choices®: Building a systems approach to advance care planning. LaCrosse, WI: Gundersen Health Systems; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hammes BJ, Klevan J, Kempf M, et al. Pediatric advance care planning. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2005;8:766–773. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinds PS, Drew D, Oakes LL, et al. End-of-life preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;23:9146–9154. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson DG, Tobin DR. End-of-life conversations. Evolving practice and theory. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1573–1578. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.12.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legare F, Ratte S, Gravel K, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: Update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;73(3):526–535. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon ME, McCabe MA, Patel KM, et al. What do adolescents want? An exploratory study regarding end-of-life decision-making. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;35:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAiley LG, Hudson-Barr DC, Gunning RS, et al. The use of advance directives with adolescents. Pediatric Nursing. 2000;26:471–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MF. Obstacles to doctor–patient communication at the end of life. In: Steinberg MD, Youngner SJ, editors. End-of-life decisions: A psychosocial perspective. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1998. pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- Pousset G, Bilsen J, De Wilde J, et al. Attitudes of adolescent cancer survivors toward end-of-life decisions for minors. Pediatrics. 2009;12:e1142–e1148. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast TJ. Advance care planning: Pitfalls, progress and promise. Critical Care Medicine. 2001;29(Suppl 2):N34–N39. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer Y, Jezewski MA, Graves B, et al. Advance directives and end-of-life decision making: Survey of critical care nurses’ knowledge, attitude, and experience. Critical Care Nurse. 2006;26(4):30–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson K, Dyson G, Holland L, et al. An exploratory study of oncology specialists understanding of the preferences of young people living with cancer. Social Work in Health Care. 2013;52:166–190. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.737898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman E, Wolfe J. Palliative care for children with cancer. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2013;10:100–107. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldman E, Wolfe J. Palliative care for children with cancer. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2013;10(2):100–107. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman DE. A faculty development course for end-of-life care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 1998;1:35–44. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1998.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger NL, Shugarman LR, Wilkinson A. ADs and advance care planning: Report to Congress. 2008 Retrieved July 15, 2013 from http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2008/ADCongRpt.htm.

- Wiener JS, Roth J. Avoiding iatrogenic harm to patient and family while discussing goals of care near the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9(2):451–463. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener L, Ballard E, Brennan T, et al. How I wish to be remembered: The use of an advanced care planning document in adolescent and young adult populations. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2008;11(10):1309–1311. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener L, Zadeh S, Battles H, et al. Allowing adolescents and young adults to plan their end-of-life care. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):897–905. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener L, Zadeh S, Wexler L, et al. When silence is not golden: Engaging adolescents and young adults in discussions around end-of-life care. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2013;60:715–718. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieder JN, Krafchick MA, Kovach AC, et al. Physician–patient interaction: What do elders want? The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2002;102(2):73–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yedidia MJ. Transforming doctor–patient relationships to promote patient-centered care: Lessons from palliative care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2007;33(1):40–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]