Currently, close to half of the 37 million adults living with HIV/AIDS worldwide are women, and many of them are in their reproductive years (UNAIDS, 2015). Of people with HIV, on average young women and adolescent girls with HIV are contracting it 5–7 years earlier than young men (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), 2012). HIV is thus influencing women’s lives more deeply, as they are more susceptible to the disease at an age when they are experiencing rapid social development (Semprini, Hollander, Vucetich, & Gilling-Smith, 2008).

In China, heterosexual sex is currently the most common transmission route for HIV.28 Many infected women belong to the high-risk category of commercial sex workers, but a significant number are housewives or career women who have been infected by their husbands (Zhang et al., 2007). In addition to being infected through sexual contact, women can contract HIV by selling blood (this happened frequently during the 1990s in China) and by sharing needles during injection drug use (IDU) (Zhang et al., 2008). At least one third of sexually active men who have sex with men in China are married, so a woman might be married to a high-risk partner without realizing the need to take precautions against HIV/AIDS (Tucker, Chen, & Peeling, 2010). China currently faces an HIV/AIDS crisis in which increasing numbers of HIV-positive individuals will need antiretroviral therapy and psychosocial support to cope with the diagnosis and ongoing treatment (Gill, Huang, & Lu, 2007; Ji, Li, Lin, & Sun, 2007).

In many societies women have lower social and economic status, while also assuming primary care of the family (Turmen, 2003). This is true for Chinese women, for example, who are still perceived to have a gender obligation that includes continuing the family line (by bearing children) and providing care to the extended family (Zhou, 2008). Although HIV infection does not change their identities as women, it does threaten their ability to continue functioning in their traditional gender-based roles (Turmen, 2003). Facing multiple social expectations and obligations, HIV-positive Chinese women may come to doubt their personal worth and feel that they have brought shame on themselves. Families living with a member who has a chronic illness (especially HIV) vacillate between hope and despair, between suffering and possibility.

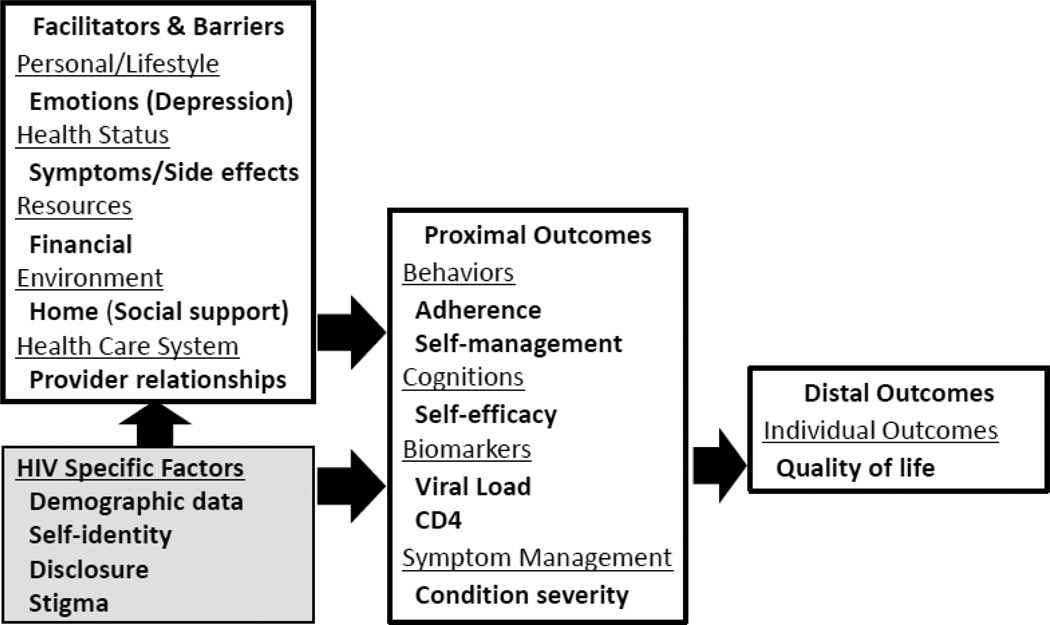

Based on Grey’s revised self- and family management theoretical framework, we updated the model to focused on HIV-positive population and develop a series of qualitative in-depth interviews, the results of which we analyzed to understand HIV-positive women’s self-management strategies (Grey, Schulman-Green, Knafl, & Reynolds, 2015). As seen in Figure 1, the framework highlights the facilitators of and barriers to the individual and family, as well as proximal and distal outcomes. We highlighted the HIV-related factors and added potential HIV-positive female specific issues (e.g., perceived stigma of HIV infection) as they will likely influence the participants’ provider relationships and QOL. The identified factors were seen as affecting reasons for and against disclosure and are weighed in decisions about disclosure. (Without disclosure, the typical HIV-positive female will not get the support she needs.) As self-management improves, stigma and clinical symptoms decrease and disclosure decisions occur. Disclosure in turn initiates family support, which has a positive effect on family dynamics and self-efficacy skills.

Figure 1.

The Self-Management Framework in HIV-Positive Chinese Women

HIV is now considered a chronic rather than terminal disease, and lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART) is needed to manage it (Lau & Tsui, 2005; Sabin et al., 2010). For HIV-positive women, managing the disease is a major concern—particularly in cultures where women have little power to regulate their sexual availability to men and are thus at increased risk for exposure to HIV (Dickens, 2008). The concerns for Chinese women living with HIV include stigma, serostatus disclosure, medication access, medication adherence, and continuation of family obligations (Jones et al., 2010; Marion et al., 2009; Voss, Portillo, Holzemer, & Dodd, 2007). There is very limited research focusing on interventions for HIV-positive women in Chinese culture, particularly in the context of self-management. Therefore, in this paper, we focus on factors that either facilitate or hinder women’s HIV-related self-management strategies.

Methods

Design

A qualitative design incorporating in-depth interviews was used for the study. Qualitative content analysis and a commercial software package (ATLAS.ti) were used to code and analyze the data.

Participants

Twenty-seven HIV-positive women were purposively sampled from two premier Chinese hospitals: Beijing’s Ditan Hospital and Shanghai’s Public Health Clinic Center (SPHCC) in China. We recruited Chinese women who were diagnosed with HIV by infectious disease physicians. The women were aged 18 years and above without significant cognitive problems and were receiving care at one the two hospitals above, either inpatient or outpatient. To be eligible for the study, the women had to be willing to share their personal experiences with us.

Data collection

Potential participants were approached directly by clinic staff and their primary care providers, who informed them about the study; those who were interested were referred to study personnel. After study staff explained the nature, risks, and benefits of the study, those who agreed to participate provided written informed consent. In this qualitative study, participants could choose whether or not to have their interviews audio recorded; if they declined, detailed notes were taken. All participants received 150 RMB (~U.S. $20) as compensation for their participation in the single semi-structured in-depth interview.

Interview process

There were two phases of in-depth interviews. The first phase was conducted between July and September of 2005 in Beijing. The second phase was conducted from November 2009 to March 2010 in Shanghai. Each of the in-depth interviews took 60–90 minutes and was conducted in a private office at the hospital or in another place of the participant’s choosing. Interviewers included research staff, physicians, and nurses at the hospital. All interviewers were Chinese speakers and interviews were conducted in Mandarin Chinese. All interviewers first completed a 2-day training course to familiarize themselves with the goals of the study and to learn standardized procedures for qualitative interviewing.

A total of 27 HIV-positive Chinese women were recruited and interviewed. After briefly introducing the study and doing a warm-up discussion, the interviewer posed questions in a conversational format. Interview guides included open-ended questions and various probes related to general experiences of HIV self-management and any facilitators and barriers the subject may have encountered. Interviewers used a checklist during the interviews to ensure that specific topics related to self-management were discussed as part of a general discussion on the women’s experience with self-management. The self-management topics included: testing history, disclosure experience, social support, medication history, side effects, adherence to ART, facilitators of and barriers to adherence, and social support. To address these topics, we asked the HIV-positive Chinese women questions like the following: How did you take care yourself after you learned you had HIV? Are you currently taking any medicine for HIV? Any issue with taking HIV medicine? How many people have you told that you are HIV-positive? What happened after you told them? Can you tell me who your support person is and describe how your support person helps you with HIV-related care? All interviews except one were audio recorded, and all were transcribed into Chinese verbatim.

Ethical considerations

Approval was obtained from the involved institutions before the study started. Written consent was obtained from each participant. Participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any time. All data were kept confidential, and the results were reported with anonymity.

Data analysis

We were using qualitative content analysis and ATLAS.ti (a commercial software package) to code and analyze the data. Immediately following each interview, the interviewer and the research team discussed the responses and added relevant notes.

After completing the interviews, researchers transcribed the conversations to Chinese. Then, the researchers coded the data and conducted a thematic content analysis following a step-by-step approach (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). The original transcripts and a draft coding system were sent to another researcher for verification and refinement. Through ongoing discussion and clarification among researchers, consensus about main findings was reached.

Several Chinese-speaking investigators trained in qualitative research methods independently reviewed the transcripts and identified codes to represent concepts in the narratives. The investigators reviewed and discussed the coding to resolve any discrepancies in the meaning and assignment of codes and general patterns observed in the data. After codes were assigned and quotes were retrieved, the researchers presented general themes, and the healthcare providers confirmed that the evolving patterns were congruent with their experiences at Ditan hospital and SPHCC. The selected quotations were then translated into English by the bilingual researchers and research assistants who led this analysis.

In this project, trustworthiness was evaluated throughout the in-depth interview process. Early analysis of the qualitative interviews was validated with a subset of interviewees to confirm the interpretation of the data via member checks (Sandelowski, 2008; Swanson, Connor, Jolley, Pettinato, & Wang, 2007). Interview data were considered credible if they represented experiences that HIV-positive Chinese women could immediately recognize as being similar to their own (Guba & Lincoln, 1981). Credibility of the data was further established through member checks. We randomly chose two sets of interviewees (including two HIV-positive Chinese women) and showed them a summary of their findings to ensure transcription accuracy. In addition to member checks, we consulted frequently with collaborators who work with this population to assure trustworthiness of the data. To enhance transferability (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004), we used data analysis to provide rich and vigorous presentation of the findings.

This report is based on a descriptive thematic analysis of the codes that related to HIV-positive women’s experiences with self-management and their understanding of the barriers and facilitators of self-management. In descriptive thematic analysis, the goal is to explicate the range and meaning of related concepts that are present in the participant narratives.

Results

Participants

The sample was composed of 27 HIV-infected Chinese women (8 from Beijing and 19 from Shanghai). A total of 93% (n=25) were ethnic Han. Of those, 19% (n=25) lived in Beijing and 67% (n=22) lived in Shanghai. The remaining participants lived in Fujien or Hubei provinces. The average age of the participants was 38 years (range 25 to 58 years old). A total of 67% had at least a high-school education (n=18). A total of 15% of the participants chose not to reveal their HIV transmission routes (n=4). Among those who did, sexual contact (n=15; 56%) and blood-to-blood transmission (n=6; 22%) were the most common transmission routes. One participant was possibly infected via intravenous drug use. The duration of the participants’ awareness of their HIV status ranged from 1 to 10 years. More than half (n=16; 59%) were married or remarried, and five of that number reported that they were divorced after learning that they had become infected with HIV. A slight majority of the participants (n=16; 59%) were on ART when the study was conducted.

Facilitators

In the content analysis phase, several themes emerged relating to protective factors women used to facilitate their self-management. These factors included family support after disclosure, learning how to live with HIV, ART adherence, and redefining the meaning of life.

Family support after disclosure

Many of the study participants talked about the support that they received from their family after they disclosed. For example, a Beijing participant said that after she disclosed her status to her parents and her brother’s family, their initial reaction was to cry. But then, after the shock and grief dissipated, they decided to support her. This 25-year-old Beijing woman said, “After I disclosed to my family, they started crying. But then, after they thought about it, they started talking about what I needed to do to be cured. They asked about whether they would need to sell the house, the car, or even all the jewelry. They wanted to do everything possible to help me rid myself of the disease. My brother and sister-in-law told me that they couldn’t accept the idea that they were going to lose me. Afterward they treated me even nicer.”

Another 25-year-old Shanghainese shared her observation that, even she did not to formally disclose to anyone in the family but one close sister, the family found out anyway. She said, “I only told my sister, but my sister told my elder brother. Then he told my second brother. Then the second brother told my younger brother. So all my sisters-in-law became aware of my disease. Then, my sister-in-law, who read a lot of magazine articles on HIV, called me and said, ‘Don’t worry, this disease cannot be transmitted to other family members.’ She taught me that the disease is only transmitted via sexual contact and maternal-fetal transmission, and she also educated my other family members. However, I was still worried about my sister, who is taking care of me. I did not want her to get the disease. I did not want to bring be a burden on her. So I told her not to visit me. But she brought herself and the other family members to do HIV testing and she showed me their results. She said, ‘See, I did not get the disease. So, don’t worry about giving your disease to your family.’ After this, I felt much better, knowing that HIV would really not be transmitted to someone through the act of caring for me.”

Married women were concerned about disclosing to their spouses. A 33-year-old married woman talked about what happened after she and her husband learned that she had the disease but he did not. She said, “He kept thinking that he was the one who gave me the disease, but my doctor told us that it might be because I used to be an intravenous drug user. So, my husband told me that it didn’t matter how I got it, and that as long as I was working with the physician, I could live for another 20 to 30 years. After my husband’s words, I felt much better. He has supported me all through my treatment.”

There were many straightforward examples of women getting support after disclosure. Others were more complicated. For example, a 55-year-old woman said, “I am the youngest in my family. After my siblings learned that I was ill, my sister decided not to come anywhere close to me or my house. She said that my house was full of disease. I was upset, so I did not invite her to my place after that. Then, my mother and my brother talked to her about it and educated her about HIV. Now she comes to my place all the time, even if I don’t invite her. She even says she wants to sleep next to me.”

Several interviewees said that they did not to disclose to their family because they did not want them to be worried. But this is a problem for Chinese people, since Chinese families are so close. One 33-year-old woman described it this way: “I feel so bad that I have not told my family that I have this disease. But I know I can’t tell them. I do not want them to worry about me. Every time they call, I cry after hanging up the phone. They wonder about me because I have gone to the hospital so frequently in the past several months. My brother keeps asking me what’s wrong with me. He even called me, sometimes three times a day. I kept telling him that I had different kinds of illnesses. Finally, he realized something was very wrong with me, and I could no longer keep it secret. Then, I told him about my disease.”

Learning to live with HIV

Some women learn of their diagnosis from an HIV-positive spouse. That is also the way in which these women learned how to take care of themselves and their sick family members. A 32-year-old woman stated, “I learned all about HIV while my spouse was in the hospital. I also learned about it from newspapers.” Another 32-year-old woman who was pregnant shared with us that she had initially searched for information about HIV online; however, this was not a good strategy for her since she felt upset after reading about the disease. Also, she doubted whether the information she got from online sources was correct. Therefore, in the end, she decided not to read anything online related to HIV. She also stated that “I don’t read HIV-related books, because I can’t read them in my office or at home, since I live with other people. If they saw me reading these books, they would know my situation. So now I only get information from my providers when I pick up my medicines.” One 33-year-old Shanghainese told us, “I feel that [HIV-related] websites in China share only horror stories, which is shocking and depressing, so I don’t like to read them. I went on websites from other countries instead. Those websites discuss a lot of information on how to live with HIV. So I read a lot of information on the progression of the disease and updated myself in the area of HIV care. And then I felt that I would be OK, that HIV is just a chronic disease. It can be controlled and is not so scary after all.”

ART adherence

After women learned about how to live with HIV, adherence became one of the important parts of their survival strategy. A 35-year-old woman in Beijing shared that “ART is a life-saving medicine. Even though it is very difficult to follow the schedule, I still try my best to take it as I should. The worst I ever do is to take it a couple hours late. When I see my CD4 jump back to normal after I follow the ART schedule, I feel so happy. That is the motivation for me to take it on time.”

Other complaints about ART include the size of the pill and the side-effects of the medication. “The ART pill is very big,” a 32-year-old woman from Beijing explained. “I need to chew it and break it into pieces before I can swallow. I had many side effects, especially when I first started doing the ART. But the doctor told me to hang in there. I felt that the doctor would never tell me anything that could hurt me, and I knew that this medicine was my guarantee of survival. I want to live, I want to see the world. Puking [as a side effect of the medication] is a piece of cake [in exchange for that]. I almost stepped into a coffin but was pulled back by the doctor. From now on, I will listen to his advice.”

Other women knew that, although the ART medicine was expensive, they needed to take it in order to survive for their family’s sake. A 40-year-old woman said, “In 2002, both my husband and I were diagnosed with HIV. My husband is too sick to work now, and I am the only person who can support the family. We don’t have the money to pay for the medicine, but the doctor is very generous and gives us some ART that was left over from other patients. I am the one who takes the ART because I am the healthiest …”

Meaning of life

All study participants talked about their expectation of their future lives. Some of them were expecting that their children would go on to fulfill the parents’ dreams. A 40-year-old woman shared that “I told my child that it is OK that I have this disease. ‘As long as I have you,’ I said, ‘you will fulfill your dreams, and you can have your life.’ That is the most important dream I have now. I told him that no one lives forever. Some children die very young and that is sad. I, at least, will live for some years longer, and currently, the government is helping me. You will need to study hard, get a degree from overseas, be a useful person, return to our country, and give yourself a better life.”

Others who didn’t have a partner talked about their disappointment in being unable to find a companion. A 59-year-old woman said, “After my husband died, my son and my boss kept telling me to find a partner. They said that I am still young and that it will be necessary to find another man to go through life together with. I kept telling them, that well, if I find a good one, that is fine. But if the person is hard to get along with, that would be very troublesome. I told them that if I was not sick, it was ok to find someone. But now I have this [HIV], and there is no way I can find a mate. So now, my only expectation is to raise my grandchild so that my son and daughter-in-law can work without worrying about the little one.”

Younger HIV-positive women without children also had a chance to think about the meaning of life, to rediscover it. A 32-year-old woman said, “After being diagnosed with HIV, I thought through many things. I used to think only about myself, but after I got this disease, I felt my parents were unfortunate to have me as a daughter. And if the outcome is not good [and I die], it will be hard for them to say goodbye. So I need to live, if only for them. And for my relatives too. I also need to live for them. I will try to live fully, as I used to. I will do things that I enjoy, visit new places and enjoy the good food. In the old days, I denied myself things, told myself to save money for the future. But now I tell myself if I want to do something I should go and do it right now. If I don’t do it now, I am not sure if I will get another chance. I realize that life has its limitations. When you lose your health, you realize that you should have appreciated it more when you had it.” Adjusting their expectations and refining their sense of the meaning of life, HIV-positive women found the strength to manage HIV-related symptoms and continue living.

Barriers

As the women shared their experiences of barriers to self-management, several risk factors were also identified, and these included lack of support, perceived stigma, physical fatigue, and financial difficulty.

Lack of support

A 40-year-old woman told us that after she accidentally disclosed her status to her brother and sister-in-law, “They did not help me at all. They even called me to ask me to return the 5,000 RMB (~$833) that I owed them. My brother did not call me at all; he never cared whether I was still alive or not. They refused to put my clothes together with theirs when doing the laundry, because they were afraid that they would get infected. Because of their attitude, I chose not to eat with them at home any longer.” Others also experienced similar isolation from the family when the disclosure was not planned. A 29-year-old woman in Shanghai described what happened when her in-laws learned suddenly that her spouse was infected. She said, “The local doctor told the family about our status, and when my parents-in-law became aware of my husband’s condition [which was full-blown AIDS] they ran away. My feeling was that my mother-in-law was putting all the responsibility of taking care of her sick son on me. At the same time, I needed to take care of my child who was only 2 years old. I was so mad. I called my father-in-law, and said, ‘Do you think your whole family is going to die? Why you are so afraid? You’re giving the responsibility of taking care of your son to me, and you’re not giving me any support. So what should I do?” Fortunately, this woman was able to get the support she needed from her siblings. Her brother volunteered to take care of her daughter while she concentrated on taking care of her spouse. Some 2 years later, her husband passed away, and her in-laws began to feel guilty for the way they had treated her. The mother-in-law regularly volunteered to cook for the family and the father-in-law called every week to make sure everything was alright.

In most of these cases, at least some close family members continued to accept the infected person unconditionally, and several of the rejecting family members eventually learned about the disease—sometimes on their own, sometimes with the help of others—and gradually came to accept their HIV-positive family member. Unfortunately, there is no way to predict who will reject an HIV-positive relative; therefore, determining when, how, and to whom to disclose becomes one of the important tasks for these women.

Stigma

Stigma is always an issue in HIV care. In this study, women shared their experiences of being hindered in self-management by stigma emanating from other people and also, sometimes, from the participants themselves. One noteworthy effect of stigma was related to sharing of food. Chinese families typically eat together and share food from the same plates and bowls, and this can be impacted by stigma. For example, a 58-year-old woman said, “My whole family knows about my diagnosis and they reacted badly. Especially in the beginning. My niece broke all her bowls and plates because I had used them. My sister told me this. I was so depressed. I thought, HIV is a horrible disease, and I am depressed from it. How can I let my whole family be depressed, too, because of my disease? When Chinese New Year came, they invited me to get together with them, and I declined. If I had known this would happen, I would not have disclosed. I thought, after I leave, they will sanitize the whole house, which will be trouble for them. After that, I decided to decline all the family get-togethers to avoid these types of situations.” Other participants experienced similar things. One 50-year-old woman shared that before disclosing, she was very close with her sister and they had always taken care of each other. One day, her sister pressed her about why she kept losing weight, and so she disclosed her status. “Then my sister’s behavior changed dramatically,” she said. “At the dining table, she always uses the dishes first then hands them to me [so she won’t come in contact with food I’ve touched]. This is discrimination. I couldn’t believe that my sister would treat me like that. Her attitude has caused me discomfort. She did not visit me again after I disclosed. I regretted that, really regretted it. I will not disclose to anyone else from now on.” After the woman lost the support of her sister, she was too depressed to seek out support from anyone else.

Physical fatigue

Many women described physical weakness as the reason they are uninterested in HIV self-management. Even if they wanted to take better care of themselves, they did not have energy to do so. One 30-year-old woman stated that “Whenever my landlord came, she always saw me lying on my bed. She said, ‘You’re young; why are you lying in bed? Have you seen a doctor?’ I told her, ‘Yeah, I visited several gynecologists but they couldn’t find any problems. I just don’t have energy to do anything.’” A 44-year-old participant echoed this sentiment, saying, “My health is bad. Even though I look fine, I am always tired. I rode my bike to the market yesterday but didn’t even have enough energy to push the pedals. I can only carry a few groceries.” A 50-year-old Shanghainese told the interviewer that she needed to stop five times before she could get to her apartment. She said, “I live on the fifth floor, and I need to stop every couple steps. I thought it was lack of exercise so I signed up for tai chi, but I withdrew after the second class. I don’t have energy to move my body at all.”

Financial difficulty

Some women talked about how lack of money limited their ability to learn about and manage their condition. They were afraid to take on things that might be beyond their ability to pay for. One 32-year-old woman had been diagnosed 5 years earlier, but she told us she could only afford two CD4 counts and one viral load test. She said, “If not for the free testing provided by the hospital, I would not be able to know what my condition is. The regular tests are so expensive that my husband and I cannot afford them. Maybe we’ll have to wait until I have AIDS.” Another study participant with multiple medication resistance said, “Because I lack money, I can’t afford any ART. Doctors give me different medicines for free, depending on whatever ART they have left over [from patients who have passed away or left the area]. If there is no extra medicine, then I don’t get any. I ended up taking many different medicines and had to stop several times, just because of my financial difficulty. If I need to pay out of pocket to buy medicine, I will stop taking ART. I just don’t have the money. I have been fortunate enough to pass through every difficulty so far.”

Discussion

HIV disclosure is essential to obtaining necessary support from family members. In addition, disclosure of serostatus can support mental health, help patients adhere to HIV treatment, decrease the likelihood of HIV transmission, and enhance self-management strategies (Jorjoran Shushtari, Sajjadi, Forouzan, Salimi, & Dejman, 2014). The most important consideration is that only by disclosing can HIV-positive individuals acquire necessary support from family members, friends, and the community. Our study participants shared that after disclosure, the family support they received not only facilitated their self-management but also helped them adhere to their daily ART regimen (Simoni et al., 2011). With good support from family, the participants were able to redefine the meaning of life and get the support they needed to live. Many of them felt they needed to “pay back” to their family for this support, not just by surviving but by living as well as they could (Chen et al., 2007).

Ironically, if an HIV-positive woman discloses to family who don’t understand HIV and who stigmatize the disease as a result, the disclosure is likely to invite unwelcome treatment. Studies have shown that HIV-positive individuals who experience stigma are less likely to seek health care and less likely to disclose their status and seek support (Cahill & Valadez, 2013). Our study participants shared that some of their siblings and relatives decreased their interactions with them following disclosure, to the point where these family members no longer even visited them, which is predicted by the experience of HIV-positive individuals in another study, who were subject to more physical and mental abuse after they had disclosed (Kalichman, Sikkema, DiFonzo, Luke, & Austin, 2002).

HIV-positive Chinese women are a hard-to-access population, as most of them put their family priorities first, taking care of themselves only after the needs of other family members are taken care of. Many of them were diagnosed only after their spouses or partners were diagnosed; had their spouses and partners not been diagnosed, it is likely that their own diagnoses would have been delayed until they had developed full-blown AIDS (Chen et al., 2011). Many ethical issues were encountered during the in-depth interviews; for example, when both of the parents were HIV-positive but they can only afford one course of medicine, the question was: who should be the one to get it? Also, should single, HIV-positive women who were sexually active disclose their status to their potential partners? And if so, when?

With free ART provided by the Chinese government, financial difficulties of purchasing the medicine have decreased (Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2009). However, the testing fees for CD4 and viral load are still a burden for some HIV-positive individuals (Moon et al., 2008). In addition, HIV-positive women are more likely to care for children and thus might experience unique stress related to childcare and childrearing (Brown, Vanable, Carey, & Elin, 2011). Having the role of caregiver for the family, HIV-positive women usually defer their dream in order to pass it along to the next generation (Chen et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2011). Women with children were particularly concerned about how to disclose their status so their children would understand what had happened to their mothers and provide support to their mothers as part of the recovery process (Yang, Leu, et al., 2015; Yang, Xie, et al., 2015).

As we learn from the theoretical model, we discover that effective self-management can improve health outcomes and improve quality of life (Richard & Shea, 2011). Women living with HIV/AIDS struggle especially to manage the many daily tasks and HIV-related symptoms (Jones et al., 2010; Marion et al., 2009; Shannon & Lee, 2008). The social context in which this self-management happens is important, and the various social roles that women perform can facilitate or hinder them from completing their self-management tasks (Webel & Higgins, 2011).

Health care providers (HCPs) should learn about the various Chinese social roles as they apply to individual patients, and particularly how these roles can be developed to increase HIV self-management. One study, for example, found that complementary therapies, talking to others, distraction techniques, physical activity, and medications are the most efficient self-management techniques for reducing daily depression (Taylor et al., 2005). These self-management strategies can alleviate the stresses associated with HIV infection.

For women who did not have a child or who had adult children, as they brought their HIV under control, they redefined the meaning of life and even, in some cases, considered finding a partner (Cahill & Valadez, 2013; Chen et al., 2015). However, even when their HIV was under control, the women worried that they would be considered “abnormal” or worried about infecting any future partner they might find (Zhou, 2008). Therefore, helping these women to decrease self-stigma and develop an efficient way to disclose if they decide to is important.

Learning to live with HIV is another facilitator for self-managing for these HIV-positive women. As Lorig and Holman mentioned “self-efficacy were associated which changes in health status” (Lorig et al., 2001), Empowering HIV-positive women to ensure they obtain the security of taking care of themselves is important. Self-efficacy is one of the essential elements to ensure that self-management programs are efficacious (Villegas et al., 2013). In addition, by educating themselves through their HCPs, peer support groups, and trustworthy Internet resources, HIV-positive women can reduce their stress and anxiety. Then by resetting their life goals and finding a meaningful way of living, these women can cope successfully with the disease over the long term.

Self-management interventions that are sensitive to gender role in China will be very helpful to address HIV-positive women’s self-identity and help them as they continue acting as caregivers of their families (Zhou, 2008). At the same time, it’s important to keep in mind that gender expectations are changing, especially in metropolitan areas like Beijing and Shanghai, where cultural influence from the West is felt most strongly (Zhan, 2004). To reduce the impact of stigma felt by HIV-positive women in China, peer support should be encouraged. Positive attitudes and guidance from peers can help these women resort life priorities, and will encourage them to take care of themselves first. When they are effectively self-managing their HIV, they can return to taking care of the family and, through helping their family (Zhou, 2009).

In summary, we analyzed the qualitative data produced by these interviews to understand strategies HIV-positive Chinese women use to facilitate their self-management as well as any factors that may be hindering them. With this analysis in hand, we can develop a culturally tailored intervention to enhance self-management in HIV-positive Chinese women. Later, we will make specific recommendations for changes in clinical care. We learned three important things in our analysis. First, we learned that disclosure of HIV status is a family matter (Li et al., 2007) and that HIV-positive women rely heavily on support from their families, and especially their close siblings, in continuing to find meaning in their lives. Second, we discovered that HCPs play an important role in encouraging HIV-positive women to manage HIV-related symptoms actively. Third, we learned that, for these women, redefining self-identity is equally important as taking care of themselves. The study participants mentioned that after being diagnosed with HIV, they were forced to redefine what life meant to them. After redefining their life goals and roles, the women could perform self-management in order to live a reasonably good life while continuing to play an important role within their families. Unfortunately, stigma against HIV is still a very severe issue in Chinese society. Therefore, decreasing stigma, and particularly self-stigma, should be one of the top goals for any self-management intervention. Well-designed interventions can encourage HIV-positive women to reach out for assistance, both within and outside their family circle (Li et al., 2013).

Limitations

There was one limitation to this study. We recruited HIV-positive women from two sites in China that differ in significant ways. Shanghai study participants, for example, tended to use ART more commonly and more effectively as compared to Beijing participants. This might be because of the time difference in data collection, since the Shanghai data were gathered several years after the Beijing data. In the intervening period, the World Health Organization issued treatment guidelines encouraging HIV-positive individuals to start ART as soon as CD4 levels drop to 5oo cells/mm3 (World Health Organization, 2015). Despite this, all participants, regardless of site, went through the same process to learn about the local healthcare system and facility; they all learned about treatment via non-governmental organizations that assisted in their HIV care.

Conclusion

The findings from this qualitative analysis highlight the facilitators of and barriers to self-management in HIV-positive Chinese women. To break the isolation of HIV-positive women in China, future studies should focus on disclosure strategies, tailoring them to enhance social support and decrease self-stigma as well as self- and family management intervention testing. This study provides valuable information for the development of HIV-related self-management interventions in China, especially for HIV-positive women. The study also has implications for programs that are tailored to populations in similar sociocultural circumstances.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported (in part) from research supported by an NIH funded program (K23NR014107; PI: Wei-Ti Chen and R34MH074364; PI: Jane Simoni). Also, other funding supported by the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (CFAR), an NIH funded program (P30 AI027757), which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers (NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NCCAM) through an international pilot grant awarded to Dr. Wei-Ti Chen. We would also like to acknowledge, Dr. Chengshi Shiu, Cheng-En Pan, the Association for the Benefit of PLWHA (Beautiful Life-Shanghai) and all of the study participants.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

References

- Brown JL, Vanable PA, Carey MP, Elin L. Computerized stress management training for HIV+ women: a pilot intervention study. AIDS Care. 2011;23(12):1525–1532. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.569699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill S, Valadez R. Growing older with HIV/AIDS: new public health challenges. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(3):e7–e15. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WT, Guthrie B, Shiu CS, Wang L, Weng Z, Li CS, Luu BV. Revising the American dream: how Asian immigrants adjust after an HIV diagnosis. J Adv Nurs. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jan.12645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WT, Lee SY, Shiu CS, Simoni JM, Pan C, Bao M, Lu H. Fatigue and sleep disturbance in HIV-positive women: a qualitative and biomedical approach. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22(9–10):1262–1269. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WT, Shiu CS, Simoni JM, Zhao H, Bao MJ, Lu H. In sickness and in health: a qualitative study of how Chinese women with HIV navigate stigma and negotiate disclosure within their marriages/partnerships. AIDS Care. 2011;23(Suppl 1):120–125. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WT, Starks H, Shiu CS, Fredriksen-Goldsen K, Simoni J, Zhang F, Zhao H. Chinese HIV-positive patients and their healthcare providers: contrasting Confucian versus Western notions of secrecy and support. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2007;30(4):329–342. doi: 10.1097/01.ANS.0000300182.48854.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens B. The Challenges of Reproductive and Sexual Rights. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(10):1738–1740. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.145490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill B, Huang Y, Lu X. Demography of HIV/AIDS in China. Washington, D.C.: 2007. Retrieved from: http://www.csis.org/media/csis/pubs/070724_china_hiv_demography.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&lists_uids=14769454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey M, Schulman-Green D, Knafl K, Reynolds NR. A revised Self- and Family Management Framework. Nurs Outlook. 2015;63(2):162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Effective Evaluation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G, Li L, Lin C, Sun S. The impact of HIV/AIDS on families and children--a study in China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S157–S161. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304712.87164.42. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18172385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) WOMEN OUT LOUD: How women living with HIV will help the world end AIDS. 2012 Retrieved from http://search.unaids.org/search.asp?lg=en&search=women%20hiv%2Faids. [Google Scholar]

- Jones DL, Owens MI, Lydston D, Tobin JN, Brondolo E, Weiss SM. Self-efficacy and distress in women with AIDS: the SMART/EST women's project. AIDS Care. 2010:1–10. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.484454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorjoran Shushtari Z, Sajjadi H, Forouzan AS, Salimi Y, Dejman M. Disclosure of HIV Status and Social Support Among People Living With HIV. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(8):e11856. doi: 10.5812/ircmj.11856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ, DiFonzo K, Luke W, Austin J. Emotional adjustment in survivors of sexual assault living with HIV-AIDS. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15(4):289–296. doi: 10.1023/A:1016247727498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JT, Tsui HY. Discriminatory attitudes towards people living with HIV/AIDS and associated factors: a population based study in the Chinese general population. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(2):113–119. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011767. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=15800086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Sun S, Wu Z, Wu S, Lin C, Yan Z. Disclosure of HIV status is a family matter: field notes from China. J Fam Psychol. 2007;21(2):307–314. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.307. doi:2007-09250-018 [pii] 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Wu Z, Liang LJ, Lin C, Guan J, Jia M, Yan Z. Reducing HIV-Related Stigma in Health Care Settings: A Randomized Controlled Trial in China. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):286–292. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, Sobel DS, Brown BW, Jr, Bandura A, Holman HR. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001;39(11):1217–1223. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11606875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marion I, Antoni M, Pereira D, Wohlgemuth W, Fletcher MA, Simon T, O'Sullivan MJ. Distress, sleep difficulty, and fatigue in women co-infected with HIV and HPV. Behav Sleep Med. 2009;7(3):180–193. doi: 10.1080/15402000902976721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S, Van Leemput L, Durier N, Jambert E, Dahmane A, Jie Y, Saranchuk P. Out-of-pocket costs of AIDS care in China: are free antiretroviral drugs enough? AIDS Care. 2008;20(8):984–994. doi: 10.1080/09540120701768446. doi:902175225 [pii] 10.1080/09540120701768446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard AA, Shea K. Delineation of self-care and associated concepts. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2011;43(3):255–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2011.01404.x. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=21884371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabin LL, DeSilva MB, Hamer DH, Xu K, Zhang J, Li T, Gill CJ. Using electronic drug monitor feedback to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-positive patients in China. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):580–589. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9615-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski MJ. Justifying qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 2008 doi: 10.1002/nur.20272. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18288640. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Semprini AE, Hollander LH, Vucetich A, Gilling-Smith C. Infertility treatment for HIV-positive women. Womens Health (Lond Engl) 2008;4(4):369–382. doi: 10.2217/17455057.4.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon M, Lee KA. HIV-infected mothers' perceptions of uncertainty, stress, depression and social support during HIV viral testing of their infants. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2008;11(4):259–267. doi: 10.1007/s00737-008-0023-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Chen WT, Huh D, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Pearson C, Zhao H, Zhang F. A preliminary randomized controlled trial of a nurse-delivered medication adherence intervention among HIV-positive outpatients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Beijing, China. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(5):919–929. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9828-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson KM, Connor S, Jolley SN, Pettinato M, Wang TJ. Contexts and evolution of women's responses to miscarriage during the first year after loss. Res Nurs Health. 2007;30(1):2–16. doi: 10.1002/nur.20175. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17243104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SJ, Candy B, Bryar RM, Ramsay J, Vrijhoef HJ, Esmond G, Griffiths CJ. Effectiveness of innovations in nurse led chronic disease management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review of evidence. BMJ. 2005;331(7515):485. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38512.664167.8F. doi:bmj.38512.664167.8F [pii] 10.1136/bmj.38512.664167.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JD, Chen XS, Peeling RW. Syphilis and social upheaval in China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;362(18):1658–1661. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911149. doi:362/18/1658 [pii] 10.1056/NEJMp0911149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turmen T. Gender and HIV/AIDS. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82(3):411–418. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00202-9. doi:S0020729203002029 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. 2014 Global Statistics. UNAIDS: The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Villegas N, Cianelli R, Gonzalez-Guarda R, Kaelber L, Ferrer L, Peragallo N. Predictors of self-efficacy for HIV prevention among Hispanic women in South Florida. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2013;24(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss J, Portillo CJ, Holzemer WL, Dodd MJ. Symptom cluster of fatigue and depression in HIV/AIDS. J Prev Interv Community. 2007;33(1–2):19–34. doi: 10.1300/J005v33n01_03. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=17298928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webel AR, Higgins PA. The Relationship Between Social Roles and Self-Management Behavior in Women Living With HIV/AIDS. Womens Health Issues. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.05.010. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=21798762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS. 2015 Retrieved from HIV/AIDS website: http://www.who.int/topics/hiv_aids/en/ Retrieved from http://www.who.int/topics/hiv_aids/en/ [Google Scholar]

- Yang JP, Leu J, Simoni JM, Chen WT, Shiu CS, Zhao H. "Please Don't Make Me Ask for Help": Implicit Social Support and Mental Health in Chinese Individuals Living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(8):1501–1509. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1041-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JP, Xie T, Simoni JM, Shiu CS, Chen WT, Zhao H, Lu H. A Mixed-Methods Study Supporting a Model of Chinese Parental HIV Disclosure. AIDS Behav. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan HJ. Through gendered lens:explaining Chinese caregivers' task performance and care reward. J Women Aging. 2004;16(1–2):123–142. doi: 10.1300/J074v16n01_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Zhao D, Chen RY. Effect of eariler initiation of antiretroviral treatment and increased treatment coverage on HIV-related mortality in China: A national observational cohort study. Lancet Infectious Disease. 2011 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70097-4. E-pub on May 19, 2011, DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(1011)70097-70094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, Zhao Y, Liu Z, Bulterys M, Chen RY. Five-year outcomes of the China National Free Antiretroviral Treatment Program. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):241–251. W-252. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00006. doi:151/4/241 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Dou Z, Yu L, Xu J, Jiao JH, Wang N, Chen RY. The effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on mortality among HIV-infected former plasma donors in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):825–833. doi: 10.1086/590945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Haberer JE, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Ma Y, Zhao D, Goosby EP. The Chinese free antiretroviral treatment program: challenges and responses. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S143–S148. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304710.10036.2b. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Citation&list_uids=18172383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YR. Endangered womanhood: Women's experiences with HIV/AIDS in China. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(8):1115–1126. doi: 10.1177/1049732308319924. doi:18/8/1115 [pii] 10.1177/1049732308319924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou YR. Help-seeking in a context of AIDS stigma: understanding the healthcare needs of people with HIV/AIDS in China. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2009;17(2):202–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00820.x. doi:HSC820 [pii] 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]