Abstract

Introduction:

In 2006, the World Health Organization launched the Global Age-Friendly Cities Project to support active aging. Canada has a large number of age-friendly initiatives; however, little is known about the effectiveness and outcomes of age-friendly community (AFC) initiatives. In addition, stakeholders report that they lack the capacity and tools to develop and conduct evaluations of their AFC initiatives. In order to address these gaps, the Public Health Agency of Canada developed indicators to support the evaluation of AFC initiatives relevant to a wide range of Canadian communities. These indicators meet the varied needs of communities, but are not designed to evaluate collective impact or enable cross-community comparisons.

Methods:

An evidence-based, iterative consultation approach was used to develop indicators for AFCs. This involved a literature review and an environmental scan. Two rounds of key expert and stakeholder consultations were conducted to rate potential indicators according to their importance, actionability and feasibility. A final list of indicators and potential measures were developed based on results from these consultations, as well as key policy considerations.

Results:

Thirty-nine indicators emerged across eight AFC domains plus four indicators related to long-term health and social outcomes. All meet the intended purpose of evaluating AFC initiatives at the community level. A user-friendly guide is available to support and share this work.

Conclusion:

The AFC indicators can help communities evaluate age-friendly initiatives, which is the final step in completing a cycle of the Pan-Canadian AFC milestones. Communities are encouraged to use the evaluation results to improve their AFC initiatives, there by benefiting a broad range of Canadians.

Keywords: age-friendly, evaluation, aging, community, Canada

Highlights

An increasing number of communities across Canada have implemented age-friendly community (AFC) initiatives. Many are ready to evaluate their activities.

Through a comprehensive review, the Public Health Agency of Canada generated potential indicators of age- friendliness that could be used for evaluation purposes. A multiphase consultation process was used to reduce and refine a long list of candidate indicators.

The final list includes 39 indicators across eight domains, as well as four indicators of health and social outcomes, that can support communities in their evaluation activities.

Introduction

In 2006, the World Health Organization (WHO) kick-started the Global Age- Friendly Cities Project by bringing together representatives from cities around the world who were interested in supporting healthy aging.1 This consultation identified eight key areas of community life where communities could become more age-friendly: outdoor spaces and buildings, transportation, housing, social participation, respect and social inclusion, civic participation and employment, communication and information, and community support and health services. Canada was a key partner in developing this approach and four Canadian cities took part in consultations that shaped the development of the model. Noting that Canada’s context includes a significant number of rural and remote communities, the federal, provincial and territorial ministers responsible for seniors sponsored a companion project that resulted in a document entitled Age-Friendly Rural and Remote Communities: A Guide.2

As part of its national leadership role to promote the development of age-friendly communities, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) developed pan-Canadian age-friendly community (AFC) milestones in collaboration with key partners. These milestones describe the steps needed to apply the AFC model in Canada as follows:

1. Establish an advisory committee that includes the active engagement of older adults;

2. Secure a local municipal council resolution to actively support, promote and work towards becoming age-friendly;

3. Establish a robust and concrete plan of action that responds to the needs identified by older adults in the community;

4. Demonstrate commitment to action by publicly posting the action plan; and

5. Commit to measuring activities, reviewing action plan outcomes and reporting on them publicly.3

Over 900 Canadian communities are currently working to become age-friendly. A number of jurisdictions and non-governmental organizations have reported that they lacked the capacity and tools to complete the fifth milestone, which is to conduct effective evaluations. In 2009, PHAC convened a meeting with key stakeholders and researchers in age-friendly communities to discuss evaluation of the AFC initiative as a whole. During this meeting, the need for indicators and data to assist community stakeholders was also identified.

In 2011, in response to mounting interest from provinces, municipalities, non-governmental organizations and Canadian researchers, PHAC undertook a rigorous process to develop a set of AFC indicators. These indicators form a menu that communities can choose from according to their unique local issues and capacities.

In this article, we describe the process undertaken by PHAC, the rationale and principles underlying the AFC indicators project and the progress to date in establishing AFC indicators.

Methods and results

Indicator identification and prioritization process

The process PHAC used to develop this set of indicators was adapted from previous, accepted methods that have been used to develop other indicator frameworks in public health.4,5,6 Generally, the development of indicators includes establishing the purpose of the indicators; designing the conceptual framework that can be based on theory, policy and/or data;4 and selecting or creating the indicators.5

The purpose of this indicator development process was to identify a menu of indicators that communities undertaking agefriendly initiatives could choose from in order to support their evaluation and monitoring activities. The overarching conceptual framework was the WHO’s Age-Friendly Cities framework, which identifies eight domains on which communities can focus to support the healthy aging of their residents.1

An Age-Friendly Indicators Working Group was established to provide input into the development of the AFC Indicators project. This Working Group, which met regularly throughout the project, comprised officials from PHAC; representatives of provincial, territorial and municipal governments; researchers; members of non-governmental organizations and seniors.

Literature review and environmental scan

The first step was to identify potential indicators through a literature review. We searched the following databases for peerreviewed literature published between 1990 and 2012: Web of Science, AgeLine, Cochrane Injuries Group trials register, CINAHL Database, MEDLINE, Health Source and Social Sciences Citation Index. Only English and French publications related to adults aged 65 years and older were retained. The search included the following terms and their combinations: seniors, elderly, older persons, evaluation, age-friendly cities/communities/hospitals/ businesses, senior-friendly communities, elder-friendly communities, visitable housing, built environment, housing, housing modification, building codes, stairs, sidewalks, transportation, social environment/inclusion, respect, employment, volunteering, outcomes, improvement, indicators of success, falls, accidents, motor vehicle accidents, road traffic accidents, communication, community support and health services.

First, we screened titles for relevance. Articles that were clearly out of scope, for example, articles about clinical care for a specific disease, were rejected at this stage. We then reviewed the abstracts for the remaining articles and included those that reported on or implied information about indicators or measures to do with age-friendly communities. Most of these articles focussed on process evaluations or short-term outcomes of the work undertaken by communities. We found no reports of completed long-term outcome evaluations of any age-friendly initiatives.

From an initial list of over 2000 documents, 23 articles were identified as relevant.

We also conducted a scan of existing AFC evaluation activities in Canada and abroad. We emailed key stakeholders in provinces, territories and selected municipalities about their activities and asked respondents to provide copies of any evaluation tools. The keywords “age-friendly” and “evaluation” were used to identify programs abroad and other relevant grey literature via the Google search engine. We retained documents from this search if they included information about existing age-friendly initiatives and/or community-based evaluations as well as information to do with indicators or measures; we found five community reports through this Internet search.7-11 A review of our files together with the online search resulted in 20 additional documents based on our criteria.

Overall, 43 documents and articles were selected for review: 12 from the United States,12-23 three multi-country international, 1,24,25 two from France,26,27 two from Australia,28,29 two from the Netherlands,30,31 and one from the United Kingdom.32 Twenty-one documents originated in Canada: five documents were from British Columbia,33-37 five from Quebec,7,38-41 four from Ontario,9,10,42,43 one from Manitoba,8 one from Saskatchewan11 and five were national in scope.44-48

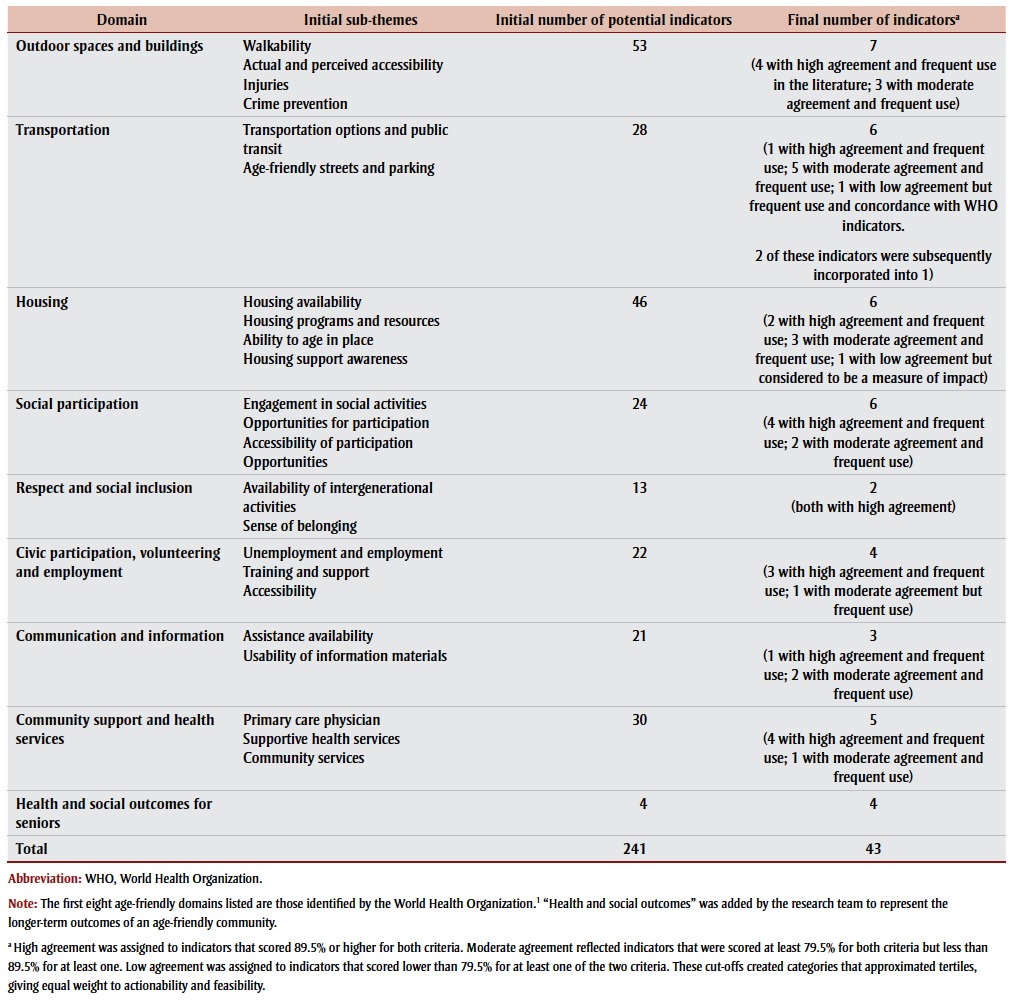

Two qualitative researchers reviewed the articles and reports, and made detailed notes on potential indicators of age-friendliness based on article contents, within each of the eight WHO-identified domains.1 This theory-driven, or deductive, approach to collecting qualitative data49 generated an initial list of 241 potential indicators. The two qualitative researchers worked together to develop sub-themes within each domain by grouping similar indicators together and identifying codes (or labels) that captured the common underlying concepts (see Table 1). This is an example of inductive, or data-driven, coding.49 The research team (made up of four members with expertise in qualitative or quantitative methods as well as content expertise in georontology and AFC) reviewed the list of potential indicators for duplication, relevance and clarity. Based on consensus, they grouped some similar concepts into a single indicator and removed concepts deemed out of scope, reducing the list to 194. A small number of indicators that originally populated the eight domains did not fit well within sub-themes, but were considered important from a healthy aging perspective; these were grouped into a new domain, “Health and Social Outcomes.” This structure was presented to the Age- Friendly Indicators Working Group for confirmation.

Table 1. Potential indicators for evaluating age-friendly communities in Canada and sub-themes.

|

We also developed a list of potential criteria based on reviewed literature and shared this with the Age-Friendly Indicators Working Group. The list of criteria included the following: evidence-based, reflecting burden, representative, available, amenable to change, understandable, repeatable, important, sound, viable, direct, objective, useful, attributable, practical and adequate. 50-53 The research team identified important/relevant, actionable and feasible as the most important criteria for selecting indicators, and confirmed this with the Working Group.

Indicator prioritization through stakeholder engagement and consultation

The second phase of the indicator selection process included two targeted stakeholder consultations aimed at reducing the list of potential indicators. These consultations were conducted using an online survey platform developed using FluidSurvey.

Consultation #1: The first consultation targeted 789 known stakeholders, including provincial and territorial representatives, municipal representatives, members of non-governmental organizations, researchers and project staff or volunteers on agefriendly projects. We identified stakeholders through existing contact lists, by the Age- Friendly Reference Group and the Age- Friendly Indicators Working Group. Respondents rated the 194 potential indicators according to their importance for measuring the age-friendliness of communities on a scale of 1 to 4, where 1 was “unimportant,” 2 “of little importance,” 3 “important,” and 4 “very important.”

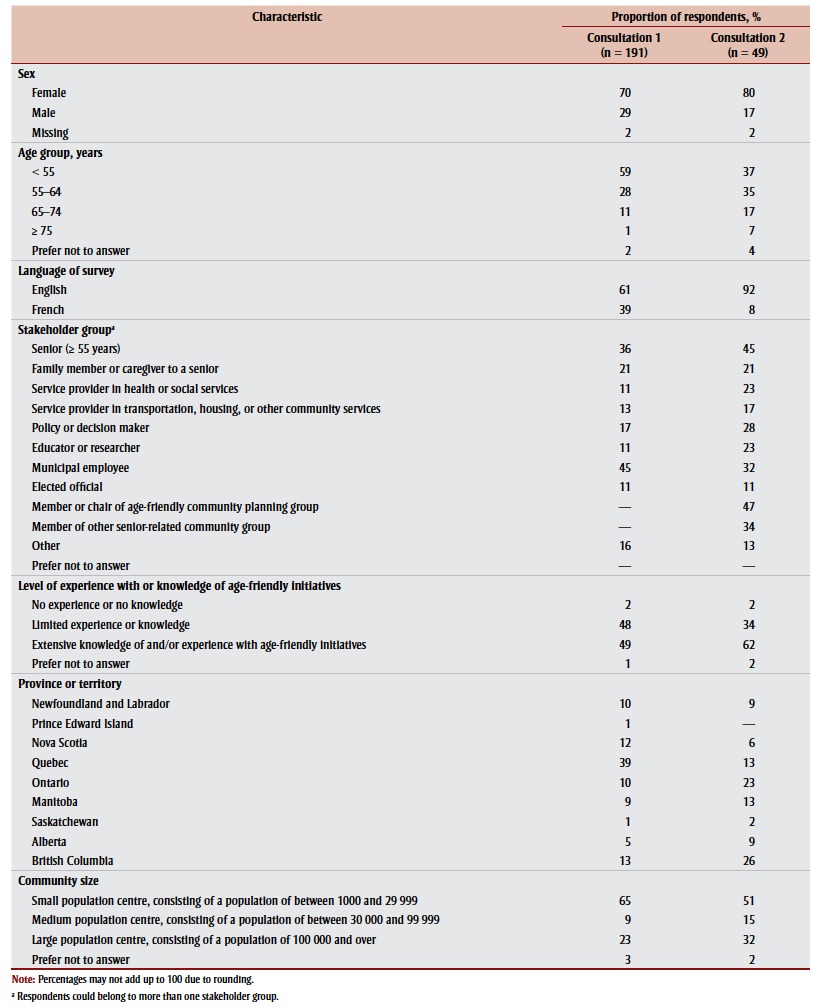

A total of 191 people responded to the first consultation survey (24% response rate). All provinces were represented, except for New Brunswick, although there were few respondents from Prince Edward Island and Saskatchewan. There were no respondents from the Territories. All of the intended stakeholder groups were represented. The majority of the respondents were female (70%), replied in English (61%) and were less than 55 years old (59%). Stakeholders lived in various sizes of community: 65% lived in centres of between 1000 and 29 999 inhabitants; 9% in centres of between 30 000 and 99 999 inhabitants; and 23% in centres of 100 000 inhabitants or more.

Table 2 shows the characteristics of respondents for the first and second consultations.

Table 2. Characteristics of respondents to consultation surveys 1 and 2 used in the process of selecting indicators for evaluating age-friendly communities in Canada.

|

The average importance rating for each indicator (on a scale of 1 to 4) ranged from a low of 2.58 to a high of 3.69. Of the top five rated indicators, three were related to enhanced health and community services and included the following:

1. Existence of programs for caregiver support (3.69 on a scale of 1 to 4)(Supportive health services)

2. Availability of low-cost food programs (3.67) (Community services)

3. Level of unmet home-care need (3.66)(Community services)

4. Existence of regulations and standards for nursing home (3.64) (Community services)

5. Number of affordable options for transportation (3.64) (Transportation options and public transit)

Based on rankings by mean importance score, the top 50% of indicators in each sub-domain were retained for further analysis. The data were also stratified by community size to examine them separately for small/medium and large communities. In the few instances where the top 50% of indicators by mean importance score were not the same in both small/medium and large communities, we added indicators to ensure inclusion of the top 50% for both of these groups. This process reduced the number of indicators to 129. A number of indicators with similar concepts were subsequently combined, reducing the list to 109.

Of the 191 respondents to the first consultation survey, 93 indicated that they would be interested in participating in a subsequent consultation survey.

Consultation #2: The aim of the second consultation survey was to further streamline the list of 109 potential indicators according to the criteria of “actionability” and “feasibility” as defined below.

For an indicator to be actionable, it can be influenced by the local or regional community, government or private sector and is likely to show change in response to action. This criterion was also used at the Age-Friendly Indicator Development Group Global Age-friendly Cities meeting50 and by the Canadian Injury Indicators Development Team.51 It is also similar to Daniel’s52 idea of changeability.

For an indicator to be feasible, data for it is measured (e.g. from a survey or administrative data) or described (e.g. with a photo or story) in a realistic manner without obstacles to collection or use. Such data can also be used to add richness and bring a program’s results to life.53 In addition, data collection methods are easy and realistic.52

Because of the response fatigue observed in the first consultation survey, the second consultation survey response choices were simplified to “yes,” “no” and “don’t know or no opinion.” Two questions concerning the preferred data collection methods for evaluation and the design of a forthcoming PHAC-produced guide were also included in this consultation.

This second survey was sent via the online survey platform to the 93 respondents to the first survey who had indicated that they would participate in a subsequent round. Of these, 49 people responded (52% response rate). As shown in Table 2, 80% of respondents were female, and 92% responded in English. Most regions in Canada as well as a wide range of stakeholder groups were represented.

We calculated the proportion of respondents who considered a given indicator actionable or feasible. Three categories were created in order to group indicators based on actionability and feasibility. High agreement was assigned to indicators that scored 89.5% or higher for both criteria. Moderate agreement reflected indicators that scored at least 79.5% for both criteria but less than 89.5% for at least one. Low agreement was assigned to indicators that scored lower than 79.5% for at least one of the two criteria. These cut-offs created categories that approximated tertiles, giving equal weight to actionability and feasibility.

A total of 38 indicators achieved high agreement, 47 achieved moderate agreement and 24 achieved low agreement.

Indicators

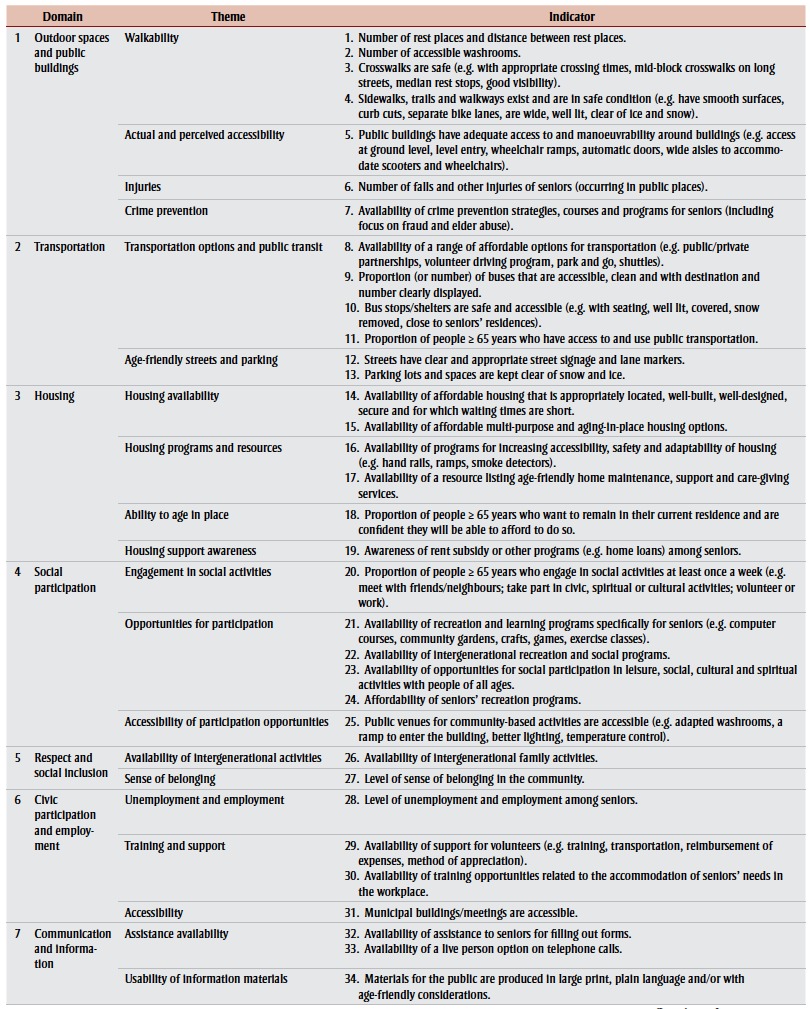

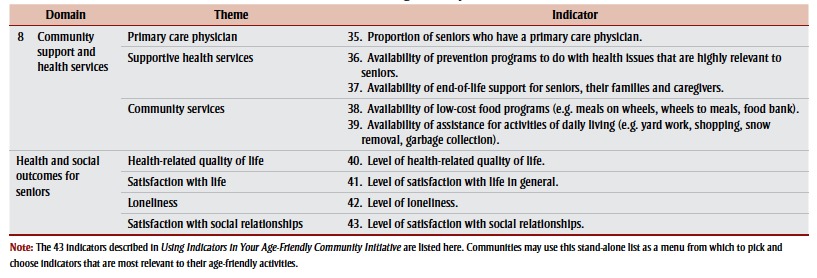

Utilizing a combination of level of agreement, frequency of appearance of concept in peer-reviewed literature and grey literature, perceived concordance with the proposed WHO indicators, and whether the indicator was a measure of impact, we selected the final list of indicators (see Table 1).

All four long-term health and social outcomes indicators were retained due to their concordance with the framework proposed by WHO at the time. This resulted in a final list of 43 indicators, shown in Table 3 by domain and theme within each domain.

Table 3. List of indicators for age-friendly communities.

|

Respondents were also asked for suggestions on developing a tool or guide to evaluate their age-friendly initiatives. The following themes emerged from analyzing their input:

The tool should have clear definitions and criteria for measuring the indicators; it should be flexible to account for unique features of a community and should have more behavioural measures.

The findings should lead to action at the community level.

Long-term outcomes should be included.

The cost of evaluations should not be a barrier (which raises the question of human and financial capacity for evaluation in communities).

During the second consultation survey, respondents were asked for ideas about the kinds of data collection methods that would be most practical for use in evaluating age-friendly initiatives. Fewer than 60% of the respondents rated the following as “very practical” or “practical”: face-to-face interviews (54%), telephone interviews (51%), stories (58%) and photographs or videotaping (56%). All the other methods (online questionnaire, paper and pencil questionnaire, observations and audits, information gathered for other purposes, administrative data, use of secondary data analysis) were rated as very practical or practical by at least 75% or more of the respondents. The most practical methods were thought to be focus groups (100%), paper-and-pencil questionnaires (91%) and use of administrative data (87%).

Results of both consultations were summarized, translated into French and shared with all participants.

Based on feedback from the consultation surveys and guidance from the Agefriendly Communities Reference Group, a range of measures were identified as potential tools for communities wishing to implement age-friendly indicators in their evaluation activities. For each indicator, one or more of five potential approaches to measurement were identified: assessment tools, accessibility tools, existing data, program inventories and surveys. Qualitative and quantitative approaches were included. Tools and existing data were identified for communities wishing to evaluate their activities. Subsequently, a user-friendly guide, Using Indicators in Your Age-Friendly Community Initiative, (available from PHAC at http://www .phac-aspc.gc.ca/seniors-aines/indicators-indicateurs-eng.php/) was developed to share the indicators, proposed measurement approaches and useful tools with communities.

Discussion

Note that the initial indicator lists were based on the literature on AFCs available when the review was conducted in 2012. At that time it was clear that the peer-reviewed and grey literature on AFCs had the following limitations: insufficient attention to specialized populations, such as ethnic groups, First Nations, and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Questioning (LGBTQ) populations; the heavy use of focus groups to seek community input (which may disadvantage those with mobility issues); a lack of consideration of specialized settings, such as nursing homes or hospitals; and finally, little emphasis on family cohesion and integration as key elements in community age-friendliness.

Since then, the literature on AFCs has grown considerably. As noted in the introduction, WHO initiated a process to identify core indicators for use by the Global Network of Age-Friendly Cities and Communities in 2011, shortly after PHAC initiated the project described in this article; WHO published a guide in 2015.54 There is considerable concordance between the indicators suggested by WHO and the menu proposed by PHAC, which is not surprising as both projects informed one another and were developed in parallel. Concepts in common include walkability; accessibility of public spaces and buildings, of public transportation and vehicles, and of public transportation stops; affordability of housing; engagement in volunteer activity, paid employment, and sociocultural activity; availability of information, health and social services; and quality of life. A recent realist review of the age-friendliness of cities in the European Healthy Cities Network clustered the eight WHO domains into three groups: physical environment, social environment and municipal services.55 Using a realist synthesis, the researchers mapped contexts; interventions; short-, mid- and long-term outcomes; and the goal of age- friendly programs. Again, the concepts identified based on existing programs using information from European cities is highly concordant with that developed through the present process, confirming our results and demonstrating transfer-ability of our findings to other Western contexts.

Strengths and limitations

The process we describe in this article was developed to yield a set of indicators, relevant to the Canadian context, that would be acceptable and helpful for communities undertaking age-friendly initiatives. Because of this, a number of methods were adopted to ensure that the process was sound and of high quality. The initial stage, reviewing the literature and identifying potential indicators, was based on qualitative methods. The credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of this initial step were central to the process.56

The credibility of these analyses is supported by the qualitative expertise of the research team, the research team’s review of coding and the use of consensus to agree on grouping similar concepts into a single indicator.

Transferability to countries similar to those described in the document review is likely. However, the identified indicators are not transferable to low- or middle-income or non-Western countries.

Dependability is supported by describing our methods to identify indicator concepts using both deductive and inductive processes.

Confirmability was supported through triangulation, by using multiple qualitative researchers during the document review process and by maintaining detailed notes during the process of identifying and reducing the initial lists of indicators.

Several factors limit the generalizability of the findings of the two consultation surveys. First, consultations were conducted with known stakeholders and may not be representative of a cross section of those with an interest in seniors and/or age- friendly work. For example, the general public was not consulted, and all stake-holders would have had some degree of familiarity with age-friendly initiatives. As a result, few respondents were aged over 75 years, and few identified themselves as belonging to a visible minority group. The most vulnerable and marginalized members of society, including those who were homeless, living at low income, living with dementia, living in institutions or without Internet access are missing from our sample.

Second, the response rates for each survey were fairly low and as a result, the final number of respondents was limited. Third, a pattern of response fatigue was identified because the proportion of missing data increased towards the end of both surveys, and a few participants commented that the surveys were excessively time consuming. Responses were visually screened for response sets (i.e. respondents entering the same response for all questions); no patterns of response set were identified.

The fact that the definitions for both criteria (actionable and feasible) included more than one concept may have confused some of those completing the second survey and caused uncertainty in interpreting the results. If a respondent answered “very actionable” to an indicator, it was not clear whether this was because they felt the appropriate level of government was involved or because the indicator was responsive to a change of policy or a new program or activity. Similarly, if an indicator was rated as “very feasible,” did the respondent mean that the data were both qualitative and quantitative or that data could be collected with ease? Future consultations should separate criteria so that only one issue is evaluated per question.

Conclusion

The number of communities engaging in age-friendly projects is increasing across Canada and many are ready to conduct evaluations of their activities. There is a strong interest in identifying shared ways to measure progress towards becoming age-friendly, the fifth pan-Canadian AFC milestone. In this article, we reported on PHAC’s process to identify and select potential AFC indicators. From an initial list of 241 indicators, we created a list of 43 indicators based on actionability and feasibility.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of Danielle Maltais and Dawn Nickel to this project.

References

- World Health Organization; Geneva (CH): 2007. Global age-friendly cities: a guide. [Google Scholar]

- FPT Ministers Responsible for Seniors. Public Health Agency of Canada; Ottawa (ON): 2009. Age-friendly rural and remote communities: a guide. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Ottawa (ON):: 2015 [updated 2016 Mar 29; cited 2016 Apr 24]. Age- friendly communities [Internet]. . Available from: http://www. phac-aspc.gc.ca/seniors-aines/afc-caa-eng.php. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer G, Davies JK, Pelikan J, Noack H, Broesskamp U, Hill C. Advancing a theoretical model for public health and health promotion indicator development: proposal from the EUHPID consortium. Eur J Public Health. 2003 Sep. 1;13((suppl 3)):107–13. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/13.suppl_1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. Statistics New Zealand; 2009 Oct. Wellington (NZ): Good practice guidelines for indicator development and reporting. Third World Forum on ‘Statistics, Knowledge and Policy’ Charting Progress, Building Visions, Improving Life; 2009 Oct 27-30; Busan, Korea. [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt MT, Roberts KC, Bennett TL, Driscoll ER, Jayaraman G, Pelletier L. Monitoring chronic diseases in Canada: the Chronic Disease Indicator Framework. Chronic Dis Inj Can. 2014;34 Suppl 1:1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu M. Garon S. Government of Québec; Québec (QC): 2007. Le projet « Villes amies des aînés » de l’OMS : un modèle international ayant fait l’objet d’une étude pilote à Sherbrooke, Québec – Quelques constats pour améliorer les conditions de vie des Québécois aînés dans nos villes. Mémoire présenté à la consultation publique sur les conditions de vie des aînés. [Google Scholar]

- Menec V, Button C, Blandford A. Centre on Aging, University of Manitoba; Winnipeg (MB): 2008. Age- friendly communities in Manitoba. Report on survey findings. [Google Scholar]

- City of Ottawa. Ottawa (ON):: [cited 2016 Apr 24]. Seniors summit consultation results [Internet]. . Available from: http://ottawa.ca/en/consultation-results. [Google Scholar]

- Wiley M. Niagara Research and Planning Council; Catharines (ON): 2011. Niagara age-friendly community initiative: year 1. 2010-2011 evaluation report. St. [Google Scholar]

- Saskatoon Council on Aging; Saskatoon (SK): 2011. Age- friendly Saskatoon initiative: findings report. [Google Scholar]

- AdvantAge Initiative. New York (NY):: 2015 [cited 2016 Apr 24]. Indicators list: essential elements of an elder friendly community [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.vnsny.org/advantage/ indicators.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kihl M, Brennan D, Gabhawala N, List J, Mittal P. AARP; Washington (DC): 2005. Livable communities: an evaluation guide. [Google Scholar]

- Clemson L, Manor D, Fitzgerald M. Behavioral factors contributing to older adults falling in public places. OTJR. 2003;23((3)):107–17. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/153944920302300304. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher N, Gretebeck KA, Robinson JC, Torres ER, Murphy SL, Martyn KK. Neighborhood factors relevant for walking in older, African American adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2010;18((1)):99–115. doi: 10.1123/japa.18.1.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehner C, Ivy A, Ramirez LK, Handy S, Brownson RC. Active neighborhood checklist: a user-friendly and reliable tool for assessing activity friendliness. Am J Health Promot. 2007;21((6)):534–7. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.6.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooker SP, Cirill L, Wicks L. Walkable neighborhoods for seniors: the Alameda County experience. J Appl Gerontol. 2007;26:157–81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0733464807299997. [Google Scholar]

- Michael YL, Green MK, Farquhar SA. Neighborhood design and active aging. Health Place. 2006;12:734–40. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, King A, Riebe D, Ory M. Measuring physical activity in older adults: use of the Community Health Activities Model Program for Seniors Physical Activity Questionnaire and the Yale Physical Activity Survey in three behavior change consortium studies. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30((6)):673–89. doi: 10.1177/0193945907311320. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0193945907311320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shendell DG, Johnson ML, Sanders DL, et al. Community built environment factors and mobility around senior wellness centers: the concept of “safe senior zones”. J Environ Health. 2011;73((7)):9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Area Agencies et al. National Association of Area Agencies on Aging; Washington (DC): 2006. The maturing of America: getting communities on track for an aging population. [Google Scholar]

- Creating an age-friendly NYC one neighborhood at a time: a toolkit for establishing an age-friendly neighborhood in your community. Joint publication of the Age. 2012:Joint publication of the Age–Friendly NYC. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. Let us in: why southern Nevada needs visitable homes. Desert Companion. 2011 Jan 27-30;;62 [Google Scholar]

- Modlich R. Age-friendly communities: a women’s issue. Women and Environments International Magazine. 2011;84/85 [Google Scholar]

- Turner C, Nixon J, McClure R. The Cochrane Collaboration, John Wiley & Sons Ltd; London (UK): 2009. The ‘WHO Safe Communities’ model for the prevention of injury in whole populations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrif T, Rioux L. Les pratiques des espaces verts urbains par les personnes âgées. L’exemple du parc de Bercy. Pratiques psychologiques. 2011;17:5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pochet P, Corget R. Entre « automobilité », proximité et sédentarité, quels modèles de mobilité quotidienne pour les résidents âgés des espaces périurbains? Espace Populations Sociétés. 2010;1:69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Broome K, Nalder E, Worrall L, Boldy D. Age-friendly buses? A comparison of reported barriers and facilitators to bus use for older and younger adults. Australas J Ageing. 2010;29((1)):33–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everingham J, Petriwskyj A, Warburton J, Cuthill M, Bartlett M. Information provision for an age-friendly community. Ageing Int. 2009;34:79–98. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12126-009-9036-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist K, Timpka T, Schelp L. Evaluation of an inter-organizational prevention program against injuries among the elderly in a WHO Safe Community. Public Health. 2001;115:308–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennberg H, Hyden C, Stahl A. Barrier-free outdoor environments: older peoples’ perceptions before and after implementation of legislative directives. Transp Policy. 2010;17((6)):464–74. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.04.013. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry P, Morris J. A great place to grow older: a case study of how Manchester is developing an age- friendly city. Working with Older People. 2011;15((1)):38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle V, Gallagher E. BC Chamber of Commerce; Vancouver (BC): 2011. Creating an age-friendly business in BC. [Google Scholar]

- Gerotech Research Associates; Victoria, BC: 2010. Age- friendly British Columbia: lessons learned from October, 2007 – September, 2010. Submitted to Seniors Healthy Living Secretariat, Ministry of Healthy Living and Sport. [Google Scholar]

- Mahaffey R. Union of BC Municipalities; Richmond (BC): 2010. Planning for the future: age-friendly and disability-friendly official community plans. [Google Scholar]

- Provincial Health Services Authority; Vancouver (BC): 2008. Indicators for a healthy built environment in BC. [Google Scholar]

- Stepaniuk JA, Tuokko H, McGee P, Garrett DD, Benner EL. Impact of transit training and free bus pass on public transportation use by older drivers. Prev Med. 2008;47((3)):335–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon L, Savoie A. Gouvernement du Québec, Ministère de la Famille et des Aînés; Québec (QC): 2008. Rapport de la consultation publique sur les conditions de vie des aînés : Préparons l’avenir avec nos aînés. [Google Scholar]

- Martin V. Gouvernement du Québec, Ministère de la Famille et des Aînés; Québec (QC): 2009. Municipalité amie des aînés. Favoriser le vieillissement actif au Québec. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la Famille et des Aînés. Gouvernement du Québec; Québec (QC): 2012. Municipalité amie des aînés. Programme de soutien. [Google Scholar]

- Rochman J, Tremblay DG. University of Québec; Montréal (QC): 2010. Le soutien à la participation sociale des aînés et le programme « ville amie des aînés » au Québec. Note de recherche de l’Alliance de recherche université-communauté sur la gestion des âges et des temps sociaux, Télé-université/ Université de Québec à Montréal. [Google Scholar]

- Lockett D, Willis A, Edwards N. Through seniors’ eyes: an exploratory qualitative study to identify environmental barriers to and facilitators of walking. Can J Nurs Res. 2005;37((3)):48–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing in partnership with the Ontario Professional Planners Institute. Ontario Professional Planners Institute; Toronto (ON): 2009. Planning by design. [Google Scholar]

- Lee KK. Vancouver (BC):: 2010 Nov 14 [cited 2016 Apr 24]. Fit cities: how active design can build healthier and more sustainable communities [Internet]. . Available from: http://www.ncchpp.ca/docs/CLASP_24Nov2010_ KarenLee.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Menec VH, Means R, Keating N, Parkhurst G, Eales J. Conceptualizing age-friendly communities. Can J Aging. 2011;30:479–93. doi: 10.1017/S0714980811000237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada; Ottawa (ON): 2010. Age-friendly communication: facts, tips, ideas. [Google Scholar]

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation; Ottawa (ON): 2008. Community indicators for an aging population. Research highlight. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes MV, Willems SM. Healthy community indicators: the perils of the search and the paucity of the find. Health Promot Int. 1990;5((2)):161–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/heapro/5.2.161. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis RE. Sage; Thousand Oaks (CA): 1998. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Age- Friendly Indicator Development Group. WHO; Geneva (CH): 2012. Meeting summary: Developing indicators for the global age-friendly cities. August 30-31, 2012; St. Gallen (CH). [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Injury Indicators Development Team. British Columbia Injury Research and Prevention Unit; Vancouver (BC): 2010. Measuring injury matters: injury indicators for children and youth in Canada. Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel M. Rating health and social indicators for use with indigenous communities: a tool for balancing cultural and scientific utility. Soc Indic Res. 2009;((94)):241–56. [Google Scholar]

- USAID Center for Development Information and Evaluation. United States Agency for International Development; (6) Washington (DC): 1996. Selecting performance indicators. Performance monitoring and evaluation TIPS. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO; Geneva (CH): 2015. Measuring the age friendliness of cities: a guide to using core indicators. [Google Scholar]

- Jackisch J, Zamaro G, Green G, Huber M. Is a healthy city also an age-friendly city? Health Promot Int. 2015;30 Suppl 1:i108–17. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav039. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Sage Publications; Newbury Park (CA): 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. [Google Scholar]