Abstract

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) strives to maintain a physically and psychologically healthy, mission-ready force, and the care provided by the Military Health System (MHS) is critical to meeting this goal. Given the rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression among U.S. service members, attention has been directed to ensuring the quality and availability of programs and services targeting these and other psychological health (PH) conditions. Understanding the current quality of care for PTSD and depression is an important step toward improving care across the MHS. To help determine whether service members with PTSD or depression are receiving evidence-based care and whether there are disparities in care quality by branch of service, geographic region, and service member characteristics (e.g., gender, age, pay grade, race/ethnicity, deployment history), DoD's Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (DCoE) asked the RAND Corporation to conduct a review of the administrative data of service members diagnosed with PTSD or depression and to recommend areas on which the MHS could focus its efforts to continuously improve the quality of care provided to all service members. This study characterizes care for service members seen by MHS for diagnoses of PTSD and/or depression and finds that while the MHS performs well in ensuring outpatient follow-up following psychiatric hospitalization, providing sufficient psychotherapy and medication management needs to be improved. Further, quality of care for PTSD and depression varied by service branch, TRICARE region, and service member characteristics, suggesting the need to ensure that all service members receive high-quality care.

There is a commitment at the highest level of government to provide mental health and substance abuse treatment services for service members and their families now and in the future (Obama, 2012). Several reports have highlighted the need for close monitoring of the quality of care provided for psychological health (PH) conditions in military populations (Hoge, Auchterlonie, and Milliken, 2006; Institute of Medicine, 2013; Institute of Medicine, 2014; Tanielian and Jaycox, 2008). In response to the recent MHS review report (Department of Defense, 2014), then Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel (U.S. Secretary of Defense, 2014) called for military treatment facilities (MTFs) to create action plans for performance improvement, and called for more transparency in providing patients, providers, and policymakers with information about quality and safety performance of the MHS.

The Military Health System (MHS) serves approximately 9.6 million beneficiaries and provides physical and PH care worldwide to active-component service members, Reserve and National Guard members, and retirees, as well as their families, survivors, and some former spouses. The MHS provides care directly through MTFs (i.e., direct care), with care being supplemented for beneficiaries by civilian providers through purchased care. MHS PH programs and services focus on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment for all service members, and each service offers additional training, services, and other support programs to help improve resilience and force readiness.

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) strives to maintain a physically and psychologically healthy, mission-ready force, and the MHS is critical to meeting this goal. Given the increases in rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression among U.S. service members, attention has been directed to ensuring the quality and availability of programs and services targeting these and other conditions. Understanding the current status of care for PTSD and depression is an important step toward future efforts to improve care. DoD asked the RAND Corporation to (1) provide a descriptive baseline assessment of the extent to which providers in the MHS implement care consistent with clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for PTSD and depression and (2) examine the relationship between guideline-concordant care and clinical outcomes for these conditions.

This article describes the characteristics of active-component service members who received care for PTSD or depression through the MHS and assesses the quality of care received using quality measures derived from administrative data. We focus on active-component service members to increase the likelihood that the care they received was provided or paid for by the MHS, rather than other sources of health care. Members of the National Guard and Reserve components, retirees, and family members were not included in these analyses. In a subsequent report, we will present the results from quality measures that incorporate data from medical record review, which will focus only on care provided at MTFs (i.e., direct care). In addition, we plan to describe the results of analyses to examine the link between guideline-concordant care and outcomes, analyses that could not be included in this report due to lack of available data.

Measuring adherence to CPGs using quality measures can establish a baseline assessment of care against which future improvements can be compared. This process can also identify potential areas for quality improvement and can provide support for continuous improvement initiatives focused on the quality of PH care provided to service members. It was important to establish a baseline assessment of care because providers' adherence to the recommendations of CPGs is currently unknown for much of the care for psychological conditions in the MHS. Furthermore, there is no MHS-wide system in place to routinely assess the quality of care provided for PTSD and depression or to determine whether the care is having a positive effect on service members' outcomes. It should be noted that the diagnoses used for depression were not limited to major depressive disorder (MDD), which is the focus of the CPG. We used a more inclusive set of diagnoses (e.g., dysthymia, depressive disorder, not elsewhere classified) to align with several existing quality measures for depression. This more inclusive approach was based on the specifications of existing quality measures for depression, including those targeting MDD, which are not restricted to MDD diagnostic codes, and on field test findings indicating that some cases of MDD may be coded with non-MDD codes (National Quality Forum [NQF], 2014). Our approach increases the likelihood that patients with MDD and associated diagnoses are not missed and that quality measure results are comparable to existing specifications.

Selecting Quality Measures for PTSD and Depression Care

Quality measures, also called performance measures, provide a way to measure how well health care is being delivered. Quality measures are applied by operationalizing aspects of care recommended by CPGs using administrative data, medical records, clinical registries, patient or clinician surveys, and other data sources. Such measures provide information about the health care system and highlight areas in which providers can take action to make health care safer and more equitable (National Quality Forum, 2013). Quality measures usually incorporate operationally defined numerators and denominators, and scores are typically presented as the percentage of eligible patients who received the recommended care (e.g., percentage of patients who receive timely outpatient follow-up after inpatient hospitalization).

Based on earlier work conducted by RAND, we selected six quality measures for PTSD and six quality measures for depression as the focus of this report. These measures are described briefly below (Table 1), with detailed technical specifications provided in Appendixes A and B. These measures were selected from a larger set of candidate measures because they can be computed using only administrative data. Within each set of measures, five measures assess care described in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)/DoD CPGs, including adequate medication trial and medication management, receipt of any psychotherapy, receipt of a minimal number of visits associated with a first-line treatment (either psychotherapy or medication management), and follow-up after hospitalization. The sixth measure in each set provides information on the rate of utilization of inpatient care, which is important as a descriptive measure that allows comparing by MTF and monitoring over time.

Table 1.

Quality Measures for Patients with PTSD and Patients with Depression

| PTSD | Depression* |

|---|---|

| Medication Management | |

| Percentage of PTSD patients with a newly prescribed SSRI/SNRI medication for 60 days (PTSD-T5) |

Percentage of depression patients with a newly prescribed antidepressant medication for 12 weeks (Depression-T5a) six months (Depression-T5b)** |

| Percentage of PTSD patients newly prescribed an SSRI/SNRI with follow-up visit within 30 days (PTSD-T6) | Percentage of depression patients newly prescribed an antidepressant with a follow-up visit within 30 days (Depression-T6) |

| Psychotherapy | |

| Percentage of PTSD patients in a new treatment episode who received any psychotherapy within four months (PTSD-T8) | Percentage of depression patients in a new treatment episode who receive any psychotherapy within four months (Depression-T8) |

| Receipt of Care | |

| Percentage of PTSD patients in a new treatment episode who received four psychotherapy visits or two evaluation and management visits within the first eight weeks (PTSD-T9) | Percentage of depression patients in a new treatment episode with four psychotherapy visits or two evaluation and management visits within the first eight weeks (Depression-T9) |

| Follow-up After Hospitalization | |

|

Percentage of psychiatric inpatient hospital discharges among patients with PTSD with follow-up Within seven days of discharge (PTSD-T15a) Within 30 days of discharge (PTSD-T15b)** |

Percentage of psychiatric inpatient hospital discharges among patients with depression with follow-up Within seven days of discharge (Depression-T15a) Within 30 days of discharge (Depression-T15b)** |

| Inpatient Utilization | |

| Number of psychiatric discharges per 1,000 patients with PTSD (PTSD-RU1) | Number of psychiatric discharges per 1,000 patients with depression (Depression-RU1) |

NOTES: Codes in parentheses provide measure numbers for ease of reference to measure specifications. SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. SNRI = serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

The definition of depression for cohort entry includes more diagnostic codes than only those for MDD.

NQF-endorsed measure.

Methods and Data Sources

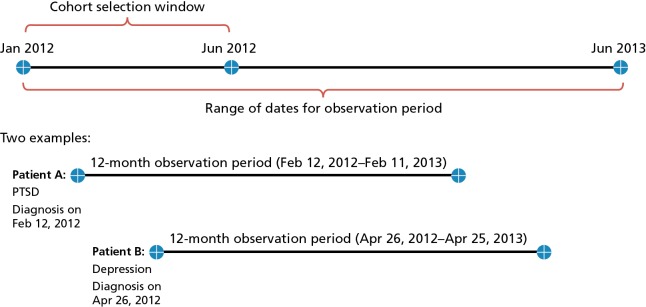

We used administrative data that contained records on all inpatient and outpatient health care encounters for MHS beneficiaries through MTF (i.e., direct care) or by civilian providers paid for by TRICARE (i.e., purchased care). To describe and evaluate care for PTSD and depression, we identified a cohort of patients who received care for PTSD and a cohort who received care for depression. Service members were eligible for the PTSD or depression cohort if they had at least one outpatient visit or inpatient stay with a primary or secondary diagnosis for PTSD or depression, respectively, during the first six months of 2012 (January 1–June 30, 2012) in either direct care or purchased care (Figure 1). When the quality measures were applied, they were applied to the smaller subgroups of patients defined by the individual measure denominators. The follow-up period starts with the date of the qualifying visit and occurs between January 1, 2012, and June 30, 2013 (Figure 1) but differs by measure.

Figure 1.

Timing of Cohort Entry and Computation of 12-Month Observation Period

The criteria for selecting these diagnostic cohorts were the following:

Active Component Service Members—The patient must have been an active-component service member during the entire 12-month observation period.

Received Care for PTSD or Depression—Service members could enter the PTSD or depression cohort if they had at least one outpatient visit or inpatient stay (direct or purchased care) with a PTSD or depression diagnosis (primary or secondary) during January through June 2012.

Engaged with and Eligible for MHS Care—Service members were eligible for a cohort if they had received a minimum of one inpatient stay or two outpatient visits for any diagnosis (i.e., related or not related to PTSD or depression) within the MHS (either direct or purchased care) during the 12-month observation period following the index visit. In addition, service members must have been eligible for TRICARE benefits during the entire 12-month observation period. Members who deployed or separated from the service during the 12-month period were excluded.

Using these criteria, we identified 14,576 service members for the PTSD cohort and 30,541 for the depression cohort. The two cohorts were not mutually exclusive, so it was possible for a service member to be in both the PTSD and depression cohorts. A total of 6,290 service members were in both cohorts, representing 43.2 percent of the PTSD cohort and 20.6 percent of the depression cohort. Most of the PTSD and depression cohort members (82.2 percent and 73.6 percent, respectively) had two or more encounters associated with a cohort diagnosis (primary or secondary) during the 12-month observation period. About 38 percent of the depression cohort had an MDD diagnosis code at some point during the observation year, while the remainder had other depression diagnoses.

To describe the quality of care for PTSD and depression delivered by the MHS, we computed performance rates for each quality measure. We examined variations in quality measure rates by service branch (Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, Navy) and TRICARE region (North, South, West, Overseas). In addition, we examined variations across service member characteristics, including age, race/ethnicity, gender, pay grade, and history of deployment at time of cohort entry.

Administrative data are particularly well suited for assessing care provision and quality across a large population, although such data do have limitations. For example, they do not include clinical detail documented in chart notes, including whether a patient refused a particular treatment or whether an evidence-based psychotherapy was delivered. A subsequent RAND report will present the results of an assessment of care quality for PTSD and depression using medical record review data, which can help fill some of these gaps and provide an even more comprehensive view of service members' care.

Characteristics of Service Members Diagnosed with PTSD and Depression, Their Care Settings, and Services Received

Demographic Characteristics

The majority of the PTSD cohort was male, non-Hispanic white, and married, and nearly half of service members in the cohort were between 25 and 34 years old. In terms of geographic location, approximately one-third resided in each of the TRICARE South and TRICARE West regions, one-quarter resided in the TRICARE North region, and the remainder resided overseas or unknown locations. Only 2 percent lived in geographic areas considered remote according to TRICARE's definition. The same patterns held for the depression cohort, though a larger percentage of that cohort was female, younger, and never married.

Soldiers represent 70 and nearly 60 percent of the PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively. Given that only 49 percent of all active-component service members are soldiers (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012), this indicates soldiers were overrepresented among those with a PTSD or depression diagnosis. Enlisted service members represented approximately 90 percent of both cohorts. Approximately 60 percent of service members in each cohort had ten or fewer years of service. In the PTSD cohort, almost 92 percent of service members had at least one deployment, while in the depression cohort, 70 percent had ever deployed. Overall, at the start of their observation period, service members in the PTSD cohort who had a history of deployment had an average of almost 20 months of deployment, and those in the depression cohort averaged 16 months.

Care Settings and Diagnoses

Patients in the PTSD and depression cohorts received the majority of their care at MTFs (over 90 percent had at least some direct care); yet one-third of patients in the PTSD cohort and a quarter in the depression cohort received at least some care from purchased care. Nearly 60 percent of all primary diagnoses coded for encounters (and presumed to be the primary reason for the encounter) in both direct care and purchased care were for non-PH diagnoses. The most common co-occurring PH conditions among both cohorts were adjustment and anxiety disorders, as well as sleep disorders or symptoms.

Approximately two-thirds of patients in the depression cohort and three-fourths of patients in the PTSD cohort received care associated with a cohort diagnosis (coded in any position, primary or secondary) from mental health specialty settings, while approximately half of each cohort had cohort-related diagnoses documented during care in primary care clinics. Further, patients saw many provider types for care associated with a cohort diagnosis. Most patients saw primary care providers, and 30 to 50 percent saw mental health care providers (primarily psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, and social workers) for this care. The median number of unique providers seen by cohort patients during the observation year at encounters with a cohort diagnosis (coded in any position) was 14 for PTSD and 12 for depression. Results suggest that patients with PTSD or depression may be seen by multiple providers across primary and specialty care, highlighting the importance of evaluating these patterns more thoroughly in future analyses to inform efforts to improve coordination of care and efficient management of these patients.

Assessment and Treatment Characteristics

Approximately 20 percent of each cohort had an inpatient hospitalization for any reason (i.e., medical or psychiatric), but a substantial proportion of these inpatient stays were associated with the cohort condition (66 percent for PTSD; 57 percent for depression). For inpatient hospitalizations that had a primary diagnosis of PTSD or depression, the median length of stay per admission was 23 days for patients in the PTSD cohort and eight days for patients in the depression cohort. The median number of outpatient encounters for any reason during the one-year observation period was 41 and 30 for PTSD and depression, respectively, suggesting high utilization of health care overall for these patients. This may be related to the high number of unique providers seen by these patients during the observation year. The majority of these visits were for non-PH conditions. The median number of visits with PTSD or depression as the primary diagnosis was ten visits and four visits, respectively.

More than two-thirds of patients in both cohorts received psychiatric diagnostic evaluation or psychological testing, while other testing and assessment methods, including neuropsychological testing and health and behavior assessment, were used with less frequency. A high proportion of patients in both cohorts received at least one visit of psychotherapy (individual, group, or family therapy)—approximately 91 percent of the PTSD cohort and 82 percent of the depression cohort. For both cohorts, individual therapy was received more frequently than group therapy, while family therapy was received least often. About 37 percent of PTSD patients and 29 percent of depression patients received more than one type of psychotherapy. If receiving psychotherapy, patients in the PTSD cohort received an average of 18 psychotherapy sessions (across therapy modalities), while approximately 14 of these visits had a PTSD diagnosis (in any position). Patients in the depression cohort received an average of 14 psychotherapy sessions, of which approximately eight of these visits had a depression diagnosis (in any position). Among patients who received psychotherapy for any diagnosis, 20 percent of both PTSD and depression patients had nine to 15 psychotherapy sessions during the observation year and 44 percent and 32 percent had 16 or more sessions (for PTSD and depression, respectively).

Approximately five in six service members of each cohort filled at least one prescription for psychotropic medication during the observation year. Among types of psychotropic medications dispensed, antidepressants were filled by the largest percentage of both cohorts (78 and 77 percent of the PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively), while stimulants were filled by the smallest percentage of both cohorts (10 percent in each cohort). Of note is the finding that about 35 percent of the PTSD cohort and 26 percent of the depression cohort filled at least one prescription for a benzodiazepine. Further examination of the use of benzodiazepines, particularly in the PTSD patients, may be worthwhile given the current PTSD CPG that discourages their use (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense, 2010). In addition to their filling prescriptions for these psychotropic medications, 53 and 59 percent of the depression and PTSD cohorts, respectively, filled at least one prescription for an opioid. In many cases, patients in the PTSD and depression cohorts filled prescriptions for more than one psychotropic medication across different medication classes or from within the same medication class. One quarter of each cohort had prescriptions from two different classes, while nearly 43 percent of the PTSD cohort and 23 percent of the depression cohort filled prescriptions from three or more classes of medications. Additionally, a notable proportion of patients in each cohort filled prescriptions for two or more psychotropic medications within the same class. These results suggest that patients in both cohorts received a wide range of psychotropic medications. These medications were in addition to any nonpsychotropic medications used that were not included in these analyses.

Quality of Care for PTSD and Depression

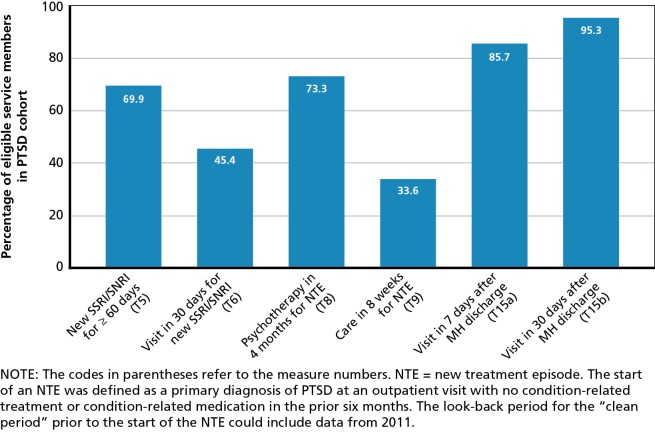

Figures 2 and 3 summarize our overall findings for each quality measure for the PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively. Each quality measure focuses on the subset of patients who met the eligibility requirements as specified in the measure denominator. As a result, 41 percent of the PTSD cohort and 47 percent of the depression cohort were included in at least one quality measure denominator (other than the two psychiatric discharge rate measures, PTSD-RU1 and Depression-RU1, for which the denominators include the entire PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively). Approximately 70 percent of active-component service members in the PTSD cohort with a new prescription for an SSRI or SNRI filled prescriptions for at least a 60-day supply. Of those in the PTSD cohort who received a new prescription for an SSRI/SNRI, only about 45 percent had a follow-up evaluation and management visit within 30 days. Nearly three-quarters of service members in the PTSD cohort with a new treatment episode received some type of psychotherapy within four months of their new PTSD diagnosis. However, only 34 percent received a minimally appropriate level of care for patients entering a new treatment episode, defined as receiving four psychotherapy visits or two evaluation and management (E&M) visits within the initial eight weeks. Rates of follow-up after hospitalization for a mental health condition were high for those in the PTSD cohort: 86 percent within seven days of discharge, and 95 percent within 30 days.

Figure 2.

Measure Rates for Eligible Active-Component Service Members in PTSD Cohort, 2012–2013

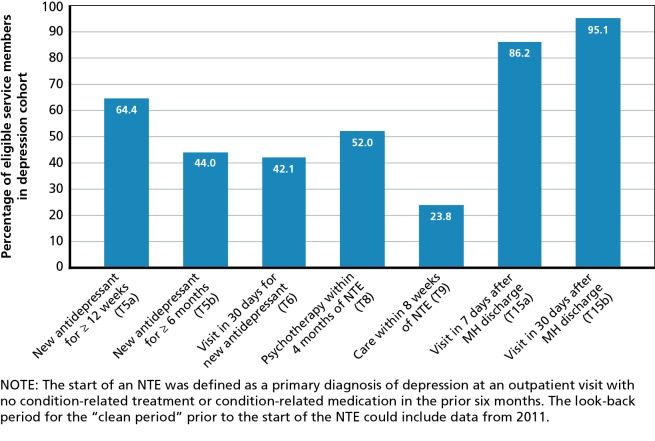

Figure 3.

Measure Rates for Active-Component Service Members in Depression Cohort, 2012–2013

In the depression cohort, almost two-thirds of service members with a new prescription for an antidepressant medication filled prescriptions for at least a 12-week supply, and 44 percent filled prescriptions for at least a six-month supply. Among those who filled a new prescription for an antidepressant, 42 percent had a follow-up evaluation and management visit within 30 days. Half of service members in the depression cohort received psychotherapy within four months of a new treatment episode of depression. Only 24 percent of service members in the depression cohort received a minimum of four psychotherapy visits or two E&M visits within the first eight weeks of their new depression diagnosis. Rates of follow-up after hospitalization for a mental health condition were high for those in the depression cohort: 86 percent within seven days of discharge, and 95 percent within 30 days.

While it is often difficult, or not appropriate, to directly compare results from other health care systems or studies or related measures, prior results for these measures (or highly related measures) are presented to provide important context to guide interpretation of the results from the current study. These comparisons serve to highlight areas where the MHS may outperform other health care systems or which may be high priorities for improvement. It should be noted that the MHS should work toward improvement on all of these measures, and the results presented provide a preliminary guide for further quality improvement efforts for PH conditions.

Variations in Care for PTSD and Depression

We also assessed the performance of each quality measure by service branch, TRICARE region, and service member characteristics, including race/ethnicity, gender, pay grade, age, and deployment history. Several large and statistically significant differences in quality of care were observed across branches of service and TRICARE region. For example, rates of follow-up within seven days after a mental health hospitalization (T15a) differed across branches of service by up to 15 percent and 14 percent in the PTSD and depression cohorts, respectively. Rates of follow-up within 30 days after a new prescription of SSRI/SNRI (T6) differed among TRICARE regions by up to 11 percent in the PTSD cohort. Rates of psychotherapy within four months of a new treatment episode (T8) also varied across TRICARE regions by up to 11 percent in the depression cohort. Similarly, we observed several large and statistically significant differences in measure rates by service member characteristics. Among service members in the PTSD and depression cohorts, rates of adequate filled prescriptions for SSRI/SNRI for PTSD (T5) and antidepressants for depression (T5a and T5b) varied by pay grade by up to 17, 22, and 29 percent, respectively. Similarly, rates of adequate filled prescriptions for SSRI/SNRI for PTSD (T5) and antidepressants for depression (T5a and T5b) varied by age by up to 11, 20, and 26 percent, respectively. Understanding these large differences in performance based on service branch, TRICARE region, and service member characteristics may be useful in designing effective quality improvement initiatives.

Policy Implications

PTSD and depression are frequent diagnoses in active-duty service members (Blakeley and Jansen, 2013). If not appropriately identified and treated, these conditions may cause morbidity that would represent a potentially significant threat to the readiness of the force. Assessment of the current quality of care for PTSD and depression is an important step toward future efforts to improve care. Yet little is known about the degree to which care provided by the MHS for these conditions is consistent with guidelines. This study provides a description of the characteristics of active-component service members who received care for PTSD and depression from the MHS (either through direct care or purchased care), along with an assessment of the quality of care provided for PTSD and depression using administrative data–based quality measures. Allowing a six-month time frame in 2012 for cohort entry, almost 15,000 and over 30,000 active-component service members were identified who received a diagnosis of PTSD and depression, respectively, from the MHS.

The analyses presented in this study have several strengths, including taking an enterprise view of care provided by the MHS as a whole, examining variations in care, and providing a baseline assessment of performance related to care for PTSD and depression using several administrative data–based quality measures. We acknowledge some limitations, including relying on diagnoses coded in administrative data, which cannot characterize detailed aspects of care or provider decision making and may contain errors or inconsistencies. In the next phase of this study, these data will be augmented with additional quality measures and data from medical record review. However, despite these limitations, this study provides a comprehensive, enterprise view of service members who receive care for PTSD or depression and a baseline assessment of the care they receive across several quality measures. We offer several policy recommendations based on the results of this study.

Improve the Quality of Care for Psychological Health Conditions Delivered by the Military Health System

The results presented in this study represent one of the largest assessments of quality of care for PTSD and depression for service members ever conducted. This assessment highlighted that, while there are key strengths in some areas, quality of care for psychological health conditions delivered by the MHS should be improved. For example, more patients should receive a follow-up medication management visit following the receipt of a new medication for PTSD or depression. While a relatively high proportion of service members received at least one psychotherapy session, a much lower proportion were found to have had four psychotherapy visits or two E&M visits within eight weeks of the start of a new treatment episode for PTSD or depression. This suggests that MHS needs to ensure that service members receive an adequate intensity of treatment following treatment initiation. The MHS also demonstrated important strengths. We observed higher quality of care in providing timely outpatient follow-up after a psychiatric hospitalization, an essential service to minimize adverse consequences for higher-risk patients. Our results suggest that the MHS has the opportunity to be a leader in providing high-quality care for psychological health conditions and should continue to pursue efforts toward this goal.

Establish an Enterprise-Wide Performance Measurement, Monitoring, and Improvement System That Includes High-Priority Standardized Metrics to Assess Care for Psychological Health Conditions

Currently, there is no enterprise-wide system for performance monitoring on quality of PH care. A separate system for PH is not necessarily required; high-priority PH measures could be integrated into an enterprise-wide system that assesses care across medical and psychological health conditions. Although the selected quality measures presented in this report highlight areas for improvement, additional quality measures for PH conditions should be developed and tested. Furthermore, an infrastructure is necessary to support the implementation of quality measures for PH conditions on a local and enterprise basis, monitoring performance, conducting analysis of performance patterns, implementing quality improvement strategies, and evaluating their effect.

Integrate Routine Outcome Monitoring for Service Members with PH Conditions as Structured Data in the Medical Record as Part of a Measurement-Based Care Strategy

Measurement-based care has become a key strategy in the implementation of clinical programs to improve mental health outcomes (Harding et al., 2011). Currently, the ability to routinely monitor clinical outcomes for patients receiving PH care in the MHS is limited. When clinicians assess patient symptoms using a structured instrument (e.g., the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire, or PHQ-9, to assess depression symptoms), the resulting score is entered as free text within a clinical note within AHLTA (formerly known as the Armed Forces Health Longitudinal Technology Application). As a consequence, scores are not available in existing administrative data. Further, these data are not easily linked with quality metrics. Routine monitoring for PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders is now mandated by policy (U.S. Department of Defense, 2013) using the Behavioral Health Data Portal (BHDP); (U.S. Department of the Army, undated), and the services are working toward full implementation of this policy. While encouraging routine symptom monitoring is a positive step, BHDP is separate from the chart, and BHDP scores must be manually entered by the clinician.

Quality Measure Results for PH Conditions Should Be Routinely Reported Internally, Enterprise-Wide, and Publicly to Support and Incentivize Ongoing Quality Improvement and to Facilitate Transparency

All health care systems can identify areas in which care should be improved. Routine internal reporting of quality measure results provides valuable information to identify gaps in quality, target quality improvement efforts, and evaluate the results of those efforts. Analyses of variations in care across service branches, TRICARE regions, or patient characteristics can also guide quality improvement efforts. Further, these data could provide a mechanism to reward or incentivize improvements in quality metrics. While VHA and civilian health care settings have used monetary incentives for providers and administrators to improve performance, the MHS could provide special recognition or awards in place of financial incentives. In addition, reporting of selected quality measures for PH conditions could be required under contracts with purchased care providers (Institute of Medicine, 2010). Reporting quality measure results externally provides transparency, which encourages accountability for high-quality care and allows comparisons with other health care systems. Finally, external reporting would allow the MHS to demonstrate improvements in performance over time to multiple stakeholders, including service members and other MHS beneficiaries, providers, and policymakers.

Investigate the Reasons for Significant Variation in Quality of Care for PH Conditions by Service Branch, Region, and Service Member Characteristics

As noted above, we found several large and statistically significant differences in measure rates by service branch, TRICARE region, and service member characteristics, many of which may represent clinically meaningful differences. Understanding and minimizing variations in care by personal characteristic (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, and geographic region) is important to ensure that care is equitable, one of the six aims of quality of care improvement in the seminal report Crossing the Quality Chasm (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Exploring the structure and processes used by MTFs and staff in high- and low-performing service branches and TRICARE regions may help to identify promising improvement strategies for, and problematic barriers to, providing high-quality care (Institute of Medicine, 2001). Analyses of performance by individual MTFs and by service member subgroups at MTFs may inform the question of how to modify structure and processes to maximize improvement. Further investigations may also determine whether some of these variations may be due to methodological considerations, thus suggesting strategies for improvement in the quality measurement process.

This study represents an important first step in describing quality of care for PTSD and depression among service members who received treatment from the MHS. The results presented here can assist the MHS in identifying high-priority next steps to support continuous improvement in the care the MHS delivers to service members and their families.

Footnotes

This research was sponsored by Department of Defense's Centers of Excellence for Psychologic Health and Traumatic Brain Injury (DCoE) and conducted within the Forces and Resources Policy Center of the RAND National Defense Research Institute.

References

- Blakeley, Katherine, and Jansen Don J., Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Other Mental Health Problems in the Military: Oversight Issues for Congress, Congressional Research Service, 7–5700, 2013. As of October 5, 2015: https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R43175.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Harding, Kelli Jane, John Rush A., Arbuckle Melissa, Trivedi Madhukar H., and Pincus Harold Alan, “Measurement-Based Care in Psychiatric Practice: A Policy Framework for Implementation,” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, Vol. 72, No. 8, 2011, pp. 1136–1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge, Charles W., Auchterlonie Jennifer L., and Milliken Charles S., “Mental Health Problems, Use of Mental Health Services, and Attrition from Military Service After Returning from Deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 295, No. 9, March 1, 2006, pp. 1023–1032. As of October 5, 2015: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16507803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Provision of Mental Health Counseling Services Under TRICARE, Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Returning Home from Iraq and Afghanistan: Readjustment Needs of Veterans, Service Members, and Their Families, Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Military and Veteran Populations: Final Assessment, Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Forum, “Who We Are,” 2013. As of October 6, 2015: http://www.qualityforum.org/story/About_Us.aspx

- National Quality Forum, “Behavioral Health Endorsement Maintenance 2014-Phase II. NQF #0105—Antidepressant Medication Management, Measure Submission and Evaluation Worksheet,” 2014. As of October 6, 2015: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2014/05/Behavioral_Health_Endorsement_Maintenance_2014_-_Phase_II.aspx

- Obama, Barack, Press Release: Executive Order—Improving Access to Mental Health Services for Veterans, Service Members, and Military Families, Washington, D.C.: The White House, Office of the Press Secretary, August 31, 2012. As of October 6, 2015: http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2012/08/31/executive-order-improving-access-mental-health-services-veterans-service [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian, Terri L., and Jaycox Lisa, eds., Invisible Wounds of War: Psychological and Cognitive Injuries, Their Consequences, and Services to Assist Recovery, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, MG-720-CCF, 2008. As of October 6, 2015: http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG720.html [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau, “Table 508. Military and Civilian Personnel in Installations: 2009,” 2012. As of November 2, 2015: https://www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/12statab/defense.pdf?cssp=SERP

- U.S. Department of the Army, “Behavioral Health Data Portal,” undated. As of October 6, 2015: http://armymedicine.mil/Pages/BHDP.aspx

- U.S. Department of Defense, Military Treatment Facility Mental Health Clinical Outcomes Guidance Memorandum, Washington, D.C., Affairs, Manpower and Reserve, Assistant Secretary of Defense, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Defense, Evaluation of the TRICARE Program, Fiscal Year 2014 Report to Congress, 2014. As of October 5, 2015: http://health.mil/Reference-Center/Reports/2014/02/25/Evaluation-of-the-TRICARE-Program

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense, “VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Version 2.0,” 2010. As of October 5, 2015: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/PTSD-full-2010c.pdf

- U.S. Secretary of Defense, “Military Health System Action Plan for Access, Quality of Care, and Patient Safety,” 2014. As of October 6, 2015: https://assets.documentcloud.org/documents/1307888/directives-from-defense-secretary-chuck-hagel.pdf