Abstract

The need for better management of chronic conditions is urgent. About 141 million people in the United States were living with one or more chronic conditions in 2010, and this number is projected to increase to 171 million by 2030. To address this challenge, many health plans have piloted and rolled out innovative approaches to improving care for their members with chronic conditions. This article documents the current range of chronic care management services, identifies best practices and industry trends, and examines factors in the plans' operating environment that limit their ability to optimize chronic care programs. The authors conducted telephone surveys with a representative sample of health plans and made in-depth case studies of six plans. All plans in the sample provide a wide range of products and services around chronic care, including wellness/lifestyle management programs for healthy members, disease management for members with common chronic conditions, and case management for high-risk members regardless of their underlying condition. Health plans view these programs as a “win-win” situation and believe that they improve care for their most vulnerable members and reduce cost of coverage. Plans are making their existing programs more patient-centric and are integrating disease and case management, and sometimes lifestyle management and behavioral health, into a consolidated chronic care management program, believing that this will increase patient engagement and prevent duplication of services and missed opportunities.

Introduction

The need for better management of chronic conditions is urgent. About 141 million people in the United States were living with one or more chronic conditions in 2010, and this number is projected to increase to 171 million by 2030, when almost every other American will be living with one or more chronic conditions (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2004). Unless these chronic conditions are managed effectively and efficiently, the implications of these numbers for morbidity and mortality, workplace productivity, and health care costs in the coming decades will be staggering. For example, one estimate projects that by 2034, the number of people with diabetes will double to 42 million and the related health care spending will triple to $336 billion (Zhuo et al., 2012). Similarly, the American Heart Association projects that by 2030, 40 percent of the U.S. population will have some form of cardiovascular disease and the related health care costs will triple from the current $273 billion to $818 billion (Heidenreich et al., 2011). Productivity losses associated with chronic diseases are projected to triple to $3.4 trillion from the current $1.1 trillion (DeVol and Bedroussian, 2007).

To address this challenge, for many years health plans have piloted and rolled out innovative approaches to improving care for their members with chronic conditions (AHIP, 2007; AHIP, 2012). Concerns about the financial sustainability of the Medicare program as well as the passage of the Affordable Care Act, which will expand employer-sponsored health coverage and Medicaid enrollment, have increased interest in these innovations in policy circles. Indeed, as reflected in several provisions of the Affordable Care Act and the priorities identified for the National Quality Strategy, promoting innovation is central to the Administration's efforts to keep public and private health coverage affordable (National Quality Forum, 2011), and learning from the private sector is a key component of this, as evidenced by the activities of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation.

Against this background, the America's Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) Foundation commissioned RAND Health to conduct a systematic assessment of chronic care management programs offered by health plans, based on a nationally representative sample. The goal of this project is to document the current range of chronic care management services, identify best practices, and elicit industry trends. We also attempt to identify factors in the plans' operating environment that limit their ability to optimize chronic care programs.

Methods

The study consisted of two phases: The first phase was a semi-structured telephone survey with a representative sample of health plans; the second, in-depth case studies of six health plans that had participated in the first phase.

For the survey, a random sample of 70 health plans in the United States was drawn from a sampling frame consisting of health plans listed in the 2011 Atlantic Information Services' (AIS's) Directory of Health Plans with commercial enrollment of 50,000 or more members. The participation rate of eligible plans was 37 percent (25 plans), representing 51 percent of all members in the sample because larger plans were more likely to participate. The survey focused on the commercial segment of the plan's enrollment with questions about the health plan, its chronic care management programs, approaches to engage patients and providers in those programs, and factors affecting the plan's operating environment.

For the case studies, six health plans were purposively selected to represent different plan sizes and regions. The case studies entailed one- to two-day visits to conduct semi-structured interviews with health plan staff members, including management, medical directors, and chronic care program staff, as well as reviews of plan documents, such as program materials, evaluation reports, and publications.

Summary of Findings

Chronic care management has become a standard component of health coverage offered by health plans regardless of size, location, and ownership status: All plans in our sample provide a wide range of products and services around chronic care, including wellness/lifestyle management programs for healthy members, disease management for members with common chronic conditions, and case management for high-risk members regardless of their underlying condition. We found that health plans view these programs as a “win-win” situation and believe that they both improve care for their most vulnerable members and reduce cost of coverage: The main drivers for program uptake are stated as containing cost growth (96 percent of surveyed plans), employer and purchaser demands (92 percent), as well as the desire to improve patient health (76 percent) and clinical care (64 percent). Further, all six case study plans include chronic care management in their fully insured products, indicating their conviction that they can offer more competitive products when providing chronic care management.

As health plans have experienced difficulties with engaging members and coordinating their activities with those of providers, they have started to customize programs to individual patients' needs and preferences and to integrate their efforts into the providers' workflows to realize the full potential of chronic care management.

Moving Toward Patient-Centric Designs

Disease and case management as the core components of chronic care management have very different legacies. Disease management was conceived as a scalable and efficient intervention for large numbers of patients with the expectation that providing standardized recommendations for medical care and self-management based on evidence would improve outcomes and reduce cost. To reach the necessary scale, it was commonly outsourced to specialized vendors. By contrast, health plans have traditionally operated case management programs themselves because the complexity and heterogeneity of member needs required customized support by an experienced nurse or social worker services and coordination with other services and benefits. This historic separation is reflected in the fact the majority of health plans responding to our survey (72 percent) continue to operate disease management and case management as two separate programs.

But our case studies show a trend to integrating disease and case management, and sometimes lifestyle management and behavioral health, into a consolidated chronic care management program with the expectation that a unified program will facilitate patient engagement and prevent both duplication of services and missed opportunities. To facilitate integration, about one-third (38 percent) of plans in our survey are bringing disease management in-house.

In addition, plans are making their existing programs more patient-centric. Disease management, which has historically been organized by disease, and sometimes even offered by disease-specific vendors, is morphing toward a holistic approach that addresses patient needs and gaps in care across multiple conditions and health risks. Indeed, the vast majority of plans are now offering an integrated disease management program that covers a member's needs across chronic conditions.

The patient-centered approach extends to member engagement and program delivery, with the emerging message being that “one size does not fit all.” Plans are using an increasing variety of communication channels—such as social media applications, video chat, and interactive voice recognition calls—to interact with program candidates and participants. Interventions are driven by members' preferences regarding which issue to handle first and tailored to their psychological states based on theories of behavior change.

Some plans are even thinking of more holistic approaches that involve the wider patient environment, including family, community, and workplace. For example, one plan that covers a Native American population is piloting a program that places a nurse on a reservation in order to provide face-to-face services not only to patients but also to tribal leaders. Another plan is actively promoting “more specialized employer-based wellness and chronic disease programs that involve working with the employer groups.”

Almost half of the plans are offering incentives to members in the form of merchandise or gift cards or lower premiums and lower cost sharing to enroll in or complete a program.

Increasing the Focus of Interventions

Chronic care management aims at stabilizing patients with chronic disease and preventing exacerbations. Like any preventive intervention, those programs can only be effective if they target the right opportunity and cost-effective if they match the resources invested to the magnitude of the opportunity. We learned that across plans, legacy programs followed a similar path: Identification of members, outreach, and program intensity (e.g., telephonic versus mailings) were mostly driven by past utilization of medical care (in particular, hospital care) and fairly standardized. But we were told that programs have evolved toward greater differentiation and sophistication in matching interventions to opportunities, not just in terms of greater patient-centricity as described above. As one plan put it, “the difference is what we do with the data—we use information such as markers for pre-diabetics to predict the future.” Typically, this new approach builds on the following components:

Analysis of past utilization combined with predictive modeling to identify members at risk of exacerbation and prioritize them for proactive interventions

Identification models using a greater range of data, such as electronic lab results and data from remote monitoring devices for biometric data, like blood pressure and heart rate

Purpose-built models that predict the risk of different events, such as different models to predict the risk of hospital admissions and the risk of high overall resource use

Targeting of specific care gaps, such as lack of medication adherence

Greater differentiation of intervention intensity, for example, using case management tools and in-person interactions for higher-risk members with distinct conditions.

Technology appears to be part of the solution. Indeed, plans express enthusiasm for the potential of remote monitoring, telemedicine, and smartphone applications in their chronic care management programs, even though these technologies have yet to be widely implemented. The challenge, as many survey respondents stressed, is the existence of many new technologies, and often only limited evidence on their impact: Thirty-six percent of plans stated that patient care technology applications were generally effective in achieving the program objectives; 20 percent of plans emphasized that the effectiveness of patient care technology applications depended on the match between the technology, the program's objective, and the targeted population; and the remainder of plans (44 percent) stated that patient care technology applications were either not effective in achieving the program objectives or that there is not enough evidence to assess their effectiveness.

Conclusions

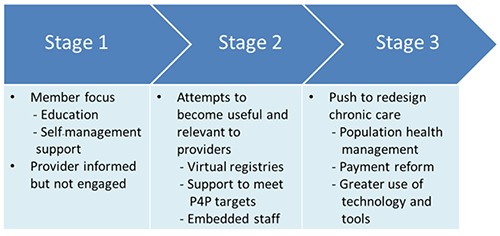

To summarize, chronic care management has become a standard benefit in commercial health insurance. Health plans' approaches to improving care for members with chronic conditions are undergoing a fundamental transformation, as Figure 1 illustrates.

Figure 1.

The Changing Face of Health Plans' Approaches to Chronic Care Management

Early attempts to support the chronically ill focused on interaction with members in the form of telephonic and sometimes in-person counseling and education. If gaps in care were discovered, members were encouraged to bring those up with their providers. Plans would notify physicians if a member enrolled in a program and alert them of care gaps, but interactions were limited. Realizing the limited impact of attempting to improve chronic care without engaging providers, plans tried to make their programs more useful and relevant for providers by providing services that directly add value to practice operations. For example, some plans maintain virtual registries of patients with chronic diseases, like diabetes, so that practices can easily review how well care is aligned with clinical guidelines. At the same time, such tools help physicians meet pay-for-performance (P4P) targets. Other plans embed staff in practices that serve as a liaison to the chronic care program for both members and practice staff.

But we also learned that health plans are increasingly realizing that programs they run themselves will have limited impact, because care decisions ultimately remain in the hands of providers. While they are continuing to offer such programs, many health plans are now going one step further by attempting not just to support current practice models but also to fundamentally transform how practices deliver care, focusing on primary care providers who treat a substantial number of a plan's members. All six of our case study plans, for example, worked with practices to adopt patient-centered medical home (PCMH) models that offer continuous management of patient needs, team-based care and expanded access including same day appointments, after-hours care, and electronic visits. Several case study plans were experimenting with gain-sharing arrangements, such as accountable care organization (ACO)–type contracts. Plans want to “provide a sliding slope to facilitate change.” Redesign efforts are flanked by changes to the payment system and substantial investment to support practices' transition. These can include free consulting support, financial assistance in the form of subsidies, and coverage of license fees for medical intelligence tools and electronic medical records (EMRs).

Lastly, an overarching theme that emerges throughout the study is that “health plans cannot do it alone” and need to bring “all stakeholders into the conversation.” Programs can only be successful if they reflect provider needs and are coordinated with their efforts. Similarly, the wider community of which the member is a part must get involved to raise health awareness and to facilitate individual behavioral change. This entails engaging and collaborating with employers—as one plan put it, “forward-thinking plan sponsors serve as good partners,” as well as providers, families and neighborhoods.

Footnotes

The research described in this article was sponsored by the America's Health Insurance Plans Foundation, and was produced within RAND Health, a division of the RAND Corporation.

References

- America's Health Insurance Plans (AHIP). (2007). Innovations in Chronic Care: A New Generation of Initiatives to Improve America's Health. Washington, D.C.: America's Health Insurance Plans. [Google Scholar]

- America's Health Insurance Plans (AHIP). (2012). Health Insurance Plans' Innovative Initiatives to Combat Cardiovascular Disease. Washington, D.C.: America's Health Insurance Plans. [Google Scholar]

- DeVol R, & Bedroussian A. (2007). An Unhealthy America: The Economic Burden of Chronic Disease. Milken Institute, October. [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, Butler J, Dracup K, Ezekowitz MD, Finkelstein EA, Hong Y, Johnston SC, Khera A, Lloyd-Jones DM, Nelson SA, Nichol G, Orenstein D, Wilson PW, Woo YJ. (2011). Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 123, 933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Forum. (2011). National Priorities Partnership. Input to the Secretary of Health and Human Services on Priorities for the National Quality Strategy. As of November 19, 2011: http://www.nationalprioritiespartnership.org/ShowContent.aspx?id=884

- Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (2004). Partnership for Solutions: Chronic Conditions: Making the Case for Ongoing Care. As of July 30, 2013: http://www.partnershipforsolutions.org/DMS/files/chronicbook2004.pdf

- Zhuo X, Zhang P, Gregg E, Barker L, Hoerger T. (2012). A nationwide community-based lifestyle program could delay or prevent Type 2 diabetes cases and save $5.7 billion in 25 years. Health Affairs 31, 50–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]