Abstract

Presents results of a one-year follow-up to the 2014 California Statewide Survey, which was developed to track attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors related to mental illness. This article focuses on items measuring stigma.

Mental illness is a highly stigmatizing condition (Link et al., 1999; Pescosolido et al., 1999). This stigma adds substantially to the challenges faced by those in emotional distress (Evans-Lacko et al., 2012) and can influence their ability to find and maintain housing, work, and social relationships (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1999). It is also thought to account for the low rates of, and substantial delays in, treatment-seeking among those experiencing mental health problems (Kessler et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2005). This adversely affects prospects for recovery and increases the burden of untreated illness on individuals and society (Sharac et al., 2010).

The California Mental Health Services Authority (CalMHSA) has undertaken a major effort to reduce the stigma of mental illness in California, with the goals of increasing social inclusion, decreasing discrimination, and increasing treatment-seeking among individuals experiencing mental health challenges. With funds from the Mental Health Services Act (Proposition 63), a 1-percent tax on annual incomes over $1 million to expand mental health services, CalMHSA developed and implemented the statewide stigma and discrimination reduction (SDR) initiative, part of a large-scale prevention and early intervention (PEI) effort to improve the mental health of Californians. The PEI program also involves initiatives for suicide prevention and improving student mental health. California's SDR initiative uses a multifaceted approach targeting institutions, communities, and individuals. The initiative includes a major social marketing campaign; creation of websites, toolkits, and other informational resources; an effort to improve media portrayals of mental illness; and thousands of in-person educational trainings and presentations occurring in all regions of the state. Other antistigma initiatives have been linked to positive changes in attitudes and reduced reports of experienced discrimination in England, Ireland, New Zealand, Australia, and Germany (Corker et al., 2013; Dietrich et al., 2010; Evans-Lacko, Henderson, and Thornicroft, 2013; Jorm, Christensen, and Griffiths, 2005; Jorm, Christensen, and Griffiths, 2006; See Change, 2012; Wyllie and Lauder, 2012). In this report, we examine whether similar shifts have occurred in California.

In an initial report on the SDR initiative (Burnam et al., 2014), RAND described findings from a surveillance tool, called the California Statewide Survey (CASS), which was developed to track attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors related to mental illness. Launched in the summer of 2013—at a point when the SDR activities were just beginning to reach full implementation—the survey provided a benchmark regarding levels of mental illness stigma among California adults. At that time, RAND found substantial levels of stigmatizing attitudes and social exclusion. RAND also found that the SDR initiative had already reached a number of California adults, even though it was still in its formative stages. More than one in ten adults was familiar with what was then a new slogan for the campaign: “Each Mind Matters.”

One year later, we find that the initiative has extended its reach considerably—one in four adults is now aware of “Each Mind Matters.” We also see several positive shifts in stigma and related attitudes and behavior. More Californians say they are willing to socialize with, live next door to, and work closely with people experiencing a mental illness than a year ago, and they describe providing greater social support to individuals they encounter who have mental health problems. We also observe meaningful increases in California residents' awareness of the stigma faced by people with mental health problems. Finally, there may have been an increase in recognition and acceptance of mental health problems.

Some findings are negative: More Californians say they would conceal a mental health problem if they had one—perhaps because of their greater awareness of stigma. And there were no improvements in beliefs about the possibility of recovery or the efficacy of treatment, or in intentions to seek treatment. In the following sections, we review our methods and results in detail and discuss their implications.

Key Findings from the Follow-Up Survey

One in four adults is now aware of “Each Mind Matters”

More Californians say they are willing to socialize with, live next door to, and work closely with people experiencing mental illness

More Californians describe providing greater social support to individuals with mental illness

Californians display meaningful increases in awareness of the stigma faced by people with mental health problems

There may have been an increase in recognition and acceptance of mental health problems.

Methods

The CASS is a longitudinal telephone survey of a sample of California adults ages 18 years and older reached through landlines and cellphones. At baseline (May–June 2013), 2,006 individuals were randomly sampled and enrolled.* They were surveyed in English or Spanish (as preferred by the respondent). To increase our ability to detect differences between key racial/ethnic groups in California targeted by CalMHSA PEI efforts, an additional sample of 567 African, Chinese, Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian Americans was collected (in August—September 2014). Most of the Asian Americans interviewed as part of this oversample chose to complete the survey in their native language. These individuals were interviewed in Mandarin, Cantonese, Vietnamese, Khmer, and Hmong. The follow-up was conducted one year later (May–September 2014). At that wave, we were able to contact and reinterview 1,285 adults (50 percent of baseline participants; see Table 1). Weights were used to align the characteristics of the sample with those of Californians, including adjustment for the Asian American and African American oversamples, and to account for study drop-out by the second wave. The resulting sample is roughly representative of the general population of California adults, although there are somewhat fewer Latinos represented than indicated by the 2013 census (U.S. Census Bureau, 2015).**

Table 1.

California Statewide Survey 2014 Respondent Characteristics (n = 1,285)

| Characteristic | Unweighted Frequency | Weighted Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 665 | 51 |

| Age at baseline | ||

| 18–29 | 195 | 22 |

| 30–39 | 171 | 17 |

| 40–49 | 215 | 19 |

| 50–64 | 401 | 25 |

| 65 or older | 303 | 16 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Latino/Hispanic | 263 | 32 |

| Non-Latino White/Caucasian | 585 | 45 |

| Non-Latino Black/African American | 183 | 5 |

| Non-Latino Asian | 169 | 13 |

| Non-Latino Other/Multiracial | 85 | 5 |

| Ever had a mental health problem at follow-up | 367 | 27 |

| Family member with mental health problem at follow-up | 706 | 53 |

We report percentages and within-sample (McNemar) tests for differences in the proportions endorsing items at baseline and follow-up (Hoffman, 1976). All significance tests are reported in the tables and figures. Differences between the CASS baseline and follow-up described in the text are statistically significant (p < 0.05) unless otherwise noted. We present percentage-point changes for other SDR campaigns as context throughout our results but do not test for statistical differences from our own findings. It is important to keep in mind that other campaigns differ in many ways from our own, including the specifics of outreach (e.g., messages, methods) and context (e.g., the country studied).

Results

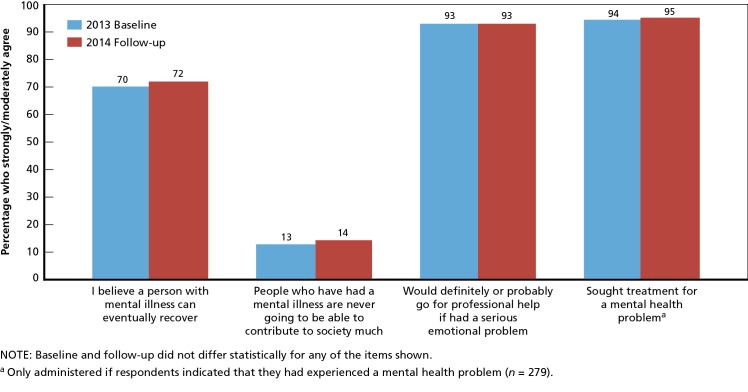

Since the 2013 baseline survey, recognition of the stigma faced by those with mental illness increased in California. Agreement that “people with mental illness experience high levels of prejudice and discrimination” was up by 5 percentage points (Figure 1). This change is greater than might have been expected over a one-year period. As a comparison, Ireland's See Change initiative reported a change of 4 percentage points after two years, from 73 percent to 77 percent, for the same item (See Change, 2012). Californians' agreement that people are caring and sympathetic toward those with mental illness decreased, consistent with a greater awareness of stigma, but the change was smaller—2 percentage points. We are not aware of any other stigma initiative that has used this measure in its evaluation, so we cannot compare it to prior studies of this item.

Figure 1.

Perceptions of Public Stigma and Support

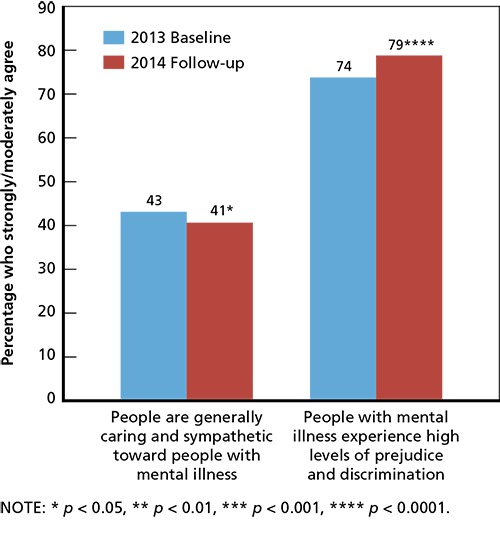

There were also reductions in social distance. The percentage of California adults unwilling to have contact with someone with a mental illness decreased by up to 5 percentage points, depending on the context of this contact (Figure 2). This represents a positive shift in social acceptance of people with mental health challenges and is much larger than shifts for similar items used to evaluate England's Time to Change (TTC) stigma-reduction campaign. Between the TTC campaign's beginning in 2009 and a 2012 survey, shifts from 0.1 to 2.3 percentage points were observed for items tapping willingness to live with, work with, work nearby, or continue a relationship with someone with a mental health problem (Evans-Lacko, Henderson, and Thornicroft, 2013). In contrast, New Zealand obtained substantial shifts (7 percentage points) in willingness to work with someone with a mental illness during the first ten months (Phase 1) of its Like Minds Like Mine campaign, but no changes in willingness to live near someone with mental illness until the most-recent campaign phase (Phase 5), which obtained a change of 5 percentage points over 20 months (Wyllie and Lauder, 2012). In this context, the shifts observed in California are fairly substantial—in the high range of prior results.

Figure 2.

Social Distance from People with Mental Illness

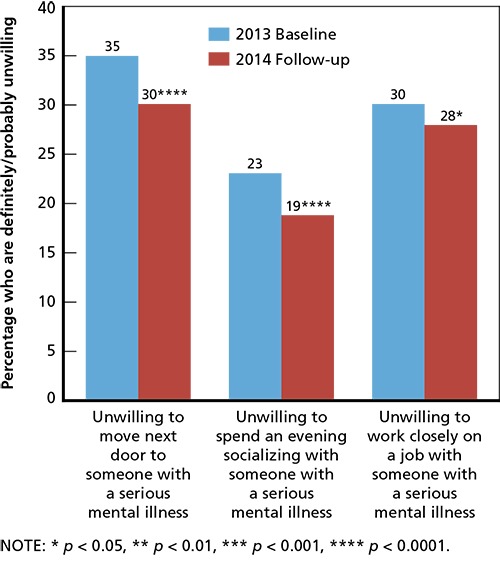

Other changes in California related to stigma were smaller than those observed for awareness and social distance. There was a two-point increase in the percentage of adults who said they had provided emotional support to someone with a mental health problem in the past year (Figure 3). Though shifts reached statistical significance only for this particular item, there were also increases in helping people to connect to other forms of support, such as community resources and professional help. This consistency suggests a positive trend toward an overall increase in social support provision to those experiencing challenges.

Figure 3.

Past-Year Social Support Provision to an Individual with a Mental Health Problem

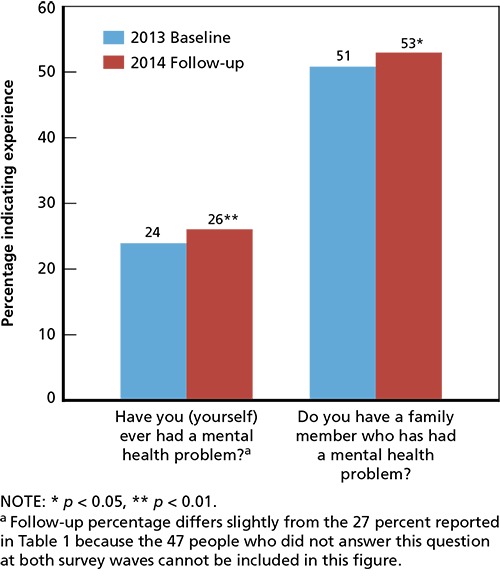

A key goal of stigma reduction is to increase recognition and acceptance of mental health problems, should they occur. From baseline to follow-up, there was an increase of 2 percentage points in Californians' reported personal experience with mental health problems, as well as an increase of 2 percentage points in reports of having a family member with a mental health problem (Figure 4). This may indicate an increase in recognition of emerging mental health challenges. In comparison, there was an uptick of 13.2 percentage points in reported experience with depression among states with higher exposure to Australia's beyondblue campaign to decrease the stigma of this diagnosis (Jorm, Christensen, and Griffiths, 2006). This occurred over the eight-year evaluation period and is equivalent to an annual increase of 1.65 percentage points. Ireland's See Change evaluation found an increase of 8 percentage points in personal experience with mental illness over a two-year period (equivalent to 4 percentage points per year), but only 7 percent of the population said they had ever been depressed at baseline, so there was more opportunity for improvement in Ireland than in California or Australia (See Change, 2012).

Figure 4.

Reported Experience with Mental Health Problems

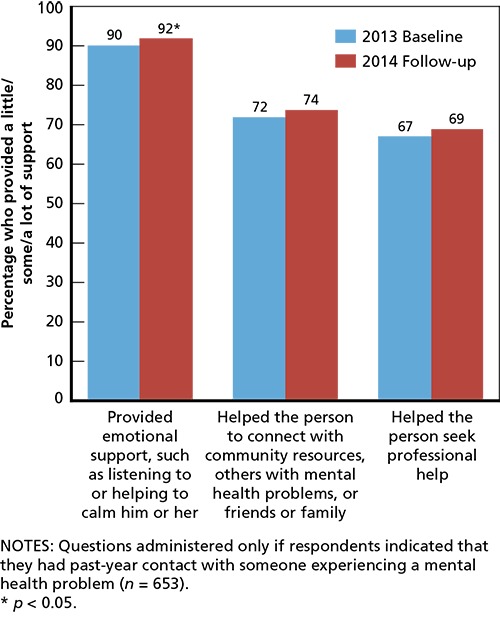

There were no changes in Californians' beliefs related to recovery or in their intended or actual treatment-seeking from baseline to follow-up (Figure 5). Results of other studies tracking these data have been mixed. Australia's beyondblue evaluation observed no changes in beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment or the likelihood of recovery following its eight-year campaign. However, a German campaign (the Nuremberg Alliance Against Depression) was associated with greater belief in the efficacy of antidepressants (an increase of 3 percentage points) and treatment by a doctor (an increase of 9 percentage points) after one year (Dietrich et al., 2010). The See Change campaign in Ireland reported an increase of 3 points over a two-year period in the percentage of people willing to seek treatment should they experience a mental health problem (See Change, 2012).

Figure 5.

Recovery and Treatment Beliefs, Intentions, and Behavior

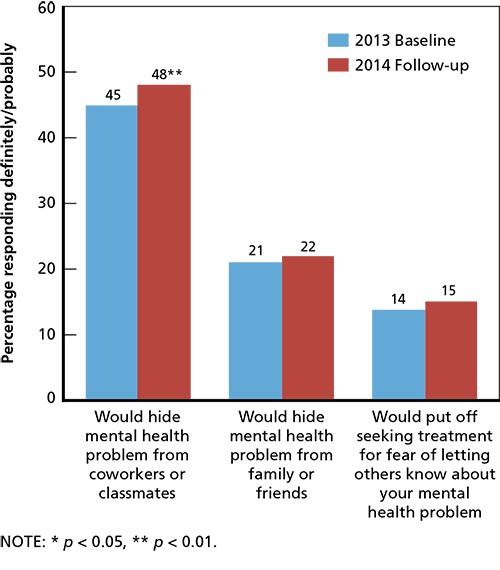

Finally, we observed a 3-point increase in the percentage of California adults who said they would hide a mental health problem from coworkers or classmates if they had one (Figure 6). Although not statistically significant, smaller increases in concealment from family and friends and intention to delay treatment out of concealment concerns were also observed. Using a similar set of items, Ireland's See Change reported an increase of 10 percentage points in treatment delay, a 9-point increase in concealment from friends, and an 11-point increase in concealment from family over two years (See Change, 2012). See Change did not ask about coworkers. Although changes in California were much smaller than in Ireland, they are still concerning and warrant continued monitoring and attention. Concealing mental health problems from some individuals may be a rational response, based on a careful balancing of the costs and benefits of disclosure in a particular environment or relationship, helping people avoid social rejection and discrimination (Corrigan, Kosyluk, and Rusch, 2013). However, the low levels of social support and delays in treatment that can also result from hiding one's condition are key targets for change in the CalMHSA PEI framework. It is possible that the slight increases observed in California are an unintended result of having increased the population's awareness of stigma. If so, it may be useful to revise some SDR campaign materials that focus on the stigma of mental illness and instead emphasize other campaign messages (e.g., expressing support for those with mental illness, noting how common mental illness is during the course of a lifetime, or discussing the effectiveness of treatment).

Figure 6.

Concealment of Mental Health Problems

Actual and Potential Exposure to CalMHSA Stigma and Discrimination Reduction Activities

As noted, CalMHSA's SDR initiative included a variety of activities. Respondents were asked about their exposure to each activity during the 12 months prior to their survey interview. Exposure to activities that were clearly “branded,” such as those from the social marketing campaign, can be specifically attributed to the SDR initiative. Other initiative activities, such as the wide variety of educational presentations given and informational materials created, occurred under a variety of organizations and labels, and other entities in the state were simultaneously conducting similar activities. Thus, it is not possible to determine whether people exposed to those activities were reached by the CalMHSA SDR initiative or by one of these other organizations. We categorized activities that could be directly linked to CalMHSA efforts as “Actual CalMHSA Reach,” and the others as “Potential Reach.” Using this method, we find that 38 percent of respondents were reached by CalMHSA's SDR initiative in the 12 months prior to the Wave 2 survey (i.e., CalMHSA Reach). This is more than twice the 17 percent of Californians reached by CalMHSA during the prior year of the SDR initiative (see the bottom of Table 2). This is a substantial expansion. A portion of the more-recent CalMHSA reach involved repeat exposure of persons who had encountered SDR messages or activities in the prior year—10 percent of Californians were reached in both years (though not necessarily via the same activities/messages). A total of 45 percent of California residents, nearly one in two adults in the state, were reached in at least one of the two years studied. By way of comparison, England's TTC campaign reached 47 percent of residents after three years, though awareness of the campaign ranged from 39 percent to 59 percent during that period, depending on the number of media messages occurring immediately prior to each assessment (Evans-Lacko, Malcolm, et al., 2013). In New Zealand, similar fluctuations were observed, with a range of 55 percent to 88 percent of the population reached over the 12 years of its initiative, depending on recency and number of television messages (Wyllie and Lauder, 2012). Because England and New Zealand incorporated more mass media (a method that is designed for high reach) than did the California SDR initiative (which relied more on other social marketing efforts), the 45 percent of Californians reached by the initiative is quite good.

Table 2.

Percentage of Actual and Potential Exposure to CalMHSA SDR Activities

| 2013 Baseline | 2014 Follow-up | Either 2013 or 2014 | Both 2013 and 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actual CalMHSA Reach | ||||

| Watched documentary “A New State of Mind: Ending the Stigma of Mental Illness” | N/A | 10 | N/A | N/A |

| Seen or heard the slogan or catch phrase “Each Mind Matters” | 12 | 19 | 25 | 5 |

| Visited the website “EachMindMatters.org”/“SanaMente.org” | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 0 |

| Seen or heard an advertisement for “ReachOut.com”/“BuscaApoyo.com” | 7 | 11 | 16 | 3 |

| Visited the website “ReachOut.com”/”BuscaApoyo.com” | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| Worn a green ribbon | N/A | 5 | N/A | N/A |

| Seen someone else wear a green ribbon | N/A | 13 | N/A | N/A |

| Had a conversation about mental health because of a green ribbon | N/A | 6 | N/A | N/A |

| Potential CalMHSA Reach | ||||

| Watched a documentary on television about mental illness | 33 | 26 | 42 | 17 |

| Seen an advertisement or promotion for a television documentary about mental illness | 35 | 29 | 48 | 17 |

| Watched some other movie or television show in which a character had a mental illness | 70 | 68 | 81 | 58 |

| Seen or heard a news story about mental illness | 77 | 70 | 86 | 62 |

| Visited another website to get information about mental illness | 15 | 14 | 22 | 7 |

| Attended an educational presentation or training either in person or online about mental illness | 17 | 13 | 23 | 7 |

| As part of your profession, received professional advice about how to discuss mental illness or interact with people who have mental illness | 23 | 20 | 31 | 12 |

| Received documents or other informational resources related to mental illness through the mail, email, online, or in person | 27 | 24 | 37 | 14 |

| Any Actual CalMHSA reach | 17 | 38 | 45 | 10 |

| Any Potential CalMHSA reach | 89 | 85 | 95 | 79 |

A much larger group, 85 percent of Californians in the past year, reported that they engaged in one or more of the types of activities that CalMHSA used to try to reduce stigma. This is just slightly lower than the 89 percent we estimated for the prior year; 95 percent of state residents were reached in at least one of these years. This indicates the potential for CalMHSA to reach 95 percent of Californians, given the methods it has been using. In the following paragraphs, we present findings on actual and potential exposure to CalMHSA SDR efforts by each specific activity, for each year.

Actual CalMHSA Reach. The CalMHSA social marketing campaign included the distribution of a one-hour documentary, “A New State of Mind: Ending the Stigma of Mental Illness,” that showcases the lives of individuals who have experienced mental health challenges and recovery. The documentary debuted on California Public Television (CPT) during primetime and was re-aired on various CPT stations at different times and days. It was also distributed through planned community events through September 2013 and through the Each Mind Matters website (www.eachmindmatters.org), which also houses a variety of other SDR materials that are part of the social marketing campaign. The site has more recently become a hub for CalMHSA PEI resources more broadly, and the logo and phrase “Each Mind Matters” now accompany all CalMHSA resources and activities. As seen in Table 2, 10 percent of respondents had viewed the SDR documentary. (Baseline data are not available for this item because the documentary aired after the administration of the survey was already under way.) One in five respondents was aware of the “Each Mind Matters” slogan—nearly 60 percent more than the percentage at baseline—and a total of one in four Californians reported awareness of Each Mind Matters across the two years assessed. Rates of visiting the Each Mind Matters website were much lower; less than 2 percent had accessed the site, and no repeat visits were made across the two years. A second part of the social marketing campaign, targeted at younger persons (ages 14 to 24 years), was the creation of an online discussion forum linked to an existing website targeting mental health information to youth, “ReachOut.com.” The ReachOut forums allow youth to seek and provide support for emotional, school, relationship, and work problems and are monitored and moderated. The ReachOut marketing campaign included radio, online, and print ads promoting the web forums, as well as posters and other supporting materials that contained campaign messages. Eleven percent of respondents had seen or heard an ad for ReachOut.com in the past year, compared with the 7 percent who reported doing so at baseline. Only 3 percent of respondents had accessed the ReachOut website. However, our survey sample does not include those ages 14 to 17, so this may be a lower estimate than we would observe if we had a younger sample fully inclusive of the targeted ages. One aspect of the SDR initiative was completely new to the year studied in the current survey—the green ribbon. Like support ribbons worn for cancer and HIV/AIDS, the green ribbon signals support for those with mental illness in California. Although green ribbons were introduced late in the campaign, 5 percent of Californians reported having worn one, 13 percent had seen someone wearing one, and 6 percent had a conversation about mental illness as a result of seeing or wearing a green ribbon.

Potential CalMHSA Reach. About one-quarter of respondents had watched a documentary on television about mental illness, and more than twice that had watched a movie or television show that featured a character with a mental illness or had seen or heard a news story about mental illness. It is possible that these individuals were exposed to stories influenced by CalMHSA media efforts. At the very least, these high rates of exposure to media portrayals of mental illness indicate that these are appropriate venues for the SDR initiative to target. About one in seven respondents had accessed websites other than Each Mind Matters or ReachOut for mental health information. Similar numbers obtained information through presentations or trainings, and more did so within the context of their profession (one in five). One in four respondents had received informational resources about mental illness via mail, email, online, or in person. In each area of potential exposure, about one-half of those reached in the most recent year were not reached in the first year assessed, so the percentage ever potentially reached by the SDR initiative is substantially higher. We also note that, in most areas of potential reach, the percentage of Californians exposed is slightly lower at follow-up compared to baseline (no significance tests were conducted for these numbers). We cannot be certain why this would be, but perhaps some people who have previously seen a documentary or news story, attended a presentation, or received information about mental illness feel their need for information has been met and fail to pursue opportunities for further exposure.

Conclusions

Across one year of the California SDR initiative, the stigma of mental illness decreased in important ways. State residents became more aware of stigma and more accepting and supportive of those with mental health challenges. They also appear more likely to recognize and report mental health problems in themselves and family members (though it is possible that these increases are due to new diagnoses over the year between surveys). Although we observed significant changes in several areas, we cannot be certain they are attributable to the SDR initiative. It is possible that these trends would have occurred without the initiative. It is also possible that the initiative led to changes larger than we observed, but these changes were countered by other forces and trends (e.g., highly publicized negative incidents where mental illness is implied to be a cause of the event). For a future report, we will test whether individuals exposed to the SDR are more likely to show changes in attitudes than those who are unexposed, and this will shed more light on the issue of campaign effectiveness. Nonetheless, it is quite possible that the initiative was responsible for the positive changes we observed. These changes are in line with those obtained by campaigns in other countries, some of which included control groups of various sorts. Findings across all of these studies are not completely consistent with one another but generally show positive shifts of modest size across a variety of measures. Some differences across studies are to be expected, given that none of the campaigns that have been studied included exactly the same activities and messages, though they have many similarities. Effectiveness of campaigns and initiatives depends upon the specifics of their implementation (Corrigan et al., 2012; Noar, 2006). The California SDR initiative has a heavy emphasis on education about and contact with persons with mental health challenges, in person or through video, which have been shown to be effective at reducing stigma in other settings (Corrigan et al., 2012).

Reach of the campaign was good, with 45 percent of Californians reporting some contact with activities and messages that can be clearly attributed to the SDR initiative across the two years of reporting. Because this estimate necessarily excludes a large swath of initiative activities, particularly educational trainings and some informational materials, actual reach is presumably higher. Moreover, it is clear that the methods in use by the SDR initiative have the potential to touch the lives of nearly every Californian. There are some apparent weaknesses in reach. Only 10 percent of respondents had contact with SDR initiative activities in both years. Although repeated exposure must be balanced against the goal of expanding reach, both are critically important in maintaining attitude and behavior changes and fostering additional improvements (Noar, 2006).

One negative change in beliefs was observed, in the area of concealment. More Californians said they would conceal a mental health problem if they had one than in our baseline survey (though only shifts in concealment from coworkers were statistically significant). As noted previously, this shift is not without precedent; it also occurred in response to Ireland's antistigma campaign. Additional analysis will be conducted for a future report to shed light on the association between awareness of stigma and likelihood of concealment. This may help to inform decisions about whether and how to refocus antistigma messages to reduce the likelihood of concealment, which may hinder people from obtaining needed support and treatment (Corrigan et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2005).

No changes were observed in beliefs about recovery or treatment, or in actual treatment-seeking. This is important because a key goal of the SDR initiative is to bring more people who need it into treatment, and to do so sooner. However, the lack of change was not unanticipated (RAND Corporation, 2012). Changes in treatment-seeking are anticipated to follow from changes in anticipated stigmatization, and so should take longer; we may be able to observe them in future surveys. Meanwhile, progress on other key goals, such as decreases in stigma and increases in social inclusion, is promising. For a future report, we will test whether these changes are greater in some subgroups than others. Mental illness stigma is greater in California among those 30 years of age and older and among some key ethnic and racial subgroups (Collins, Roth, et al., 2014; Collins, Wong, et al., 2014). It will be particularly important to determine whether stigma has declined in these populations.

This research was conducted in RAND Health, a division of the RAND Corporation.

Notes

Data collection was conducted by the Field Research Corporation based in San Francisco, California.

All baseline results reported herein are based on the weighted follow-up sample so that we can compare the same individuals over time. These estimates occasionally differ slightly from what was reported for the baseline as a whole in Burnam et al., 2014.

References

- Burnam, M. Audrey, Berry Sandra H., Cerully Jennifer L., and Eberhart Nicole K., Evaluation of the California Mental Health Services Authority's Prevention and Early Intervention Initiatives: Progress and Preliminary Findings, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, RR-438-CMHSA, 2014. As of April 17, 2015: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR438.html [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Rebecca L., Roth Elizabeth, Cerully Jennifer L., and Wong Eunice C., Beliefs Related to Mental Illness Stigma Among California Young Adults, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, RR-819-CMHSA, 2014. As of April 17, 2015: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR819.html [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Rebecca L., Wong Eunice C., Cerully Jennifer L., and Roth Elizabeth, Racial and Ethnic Differences in Mental Illness Stigma in California, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, RR-684-CMHSA, 2014. As of April 17, 2015: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR684.html [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, P., Kosyluk K., and Rusch N., “Reducing Self-Stigma by Coming Out Proud,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 103, No. 5, 2013, pp. 794–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P.W., Morris S. B., Michaels P. J., Rafacz J. D., and Rusch N., “Challenging the Public Stigma of Mental Illness: A Meta-Analysis of Outcome Studies,” Psychiatric Services, Vol. 63, No. 10, October 2012, pp. 963–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corker, E., Hamilton S., Henderson C., Weeks C., Pinfold V., Rose D., et al., “Experiences of Discrimination Among People Using Mental Health Services in England 2008–2011,” British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 202, No. s55, 2013, pp. s58–s63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich, Sandra, Mergl Roland, Freudenberg Philine, Althaus David, and Hegerl Ulrich, “Impact of a Campaign on the Public's Attitudes Towards Depression,” Health Education Research, Vol. 25, No. 1, 2010, pp. 135–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko, S., Brohan E., Mojtabai R., and Thornicroft G., “Association Between Public Views of Mental Illness and Self-Stigma Among Individuals with Mental Illness in 14 European Countries,” Psychological Medicine, Vol. 16, 2012, pp. 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko, S., Henderson C., and Thornicroft G., “Public Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviour Regarding People with Mental Illness in England 2009–2012,” British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 202 (suppl 55), 2013, pp. s51–s57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko, S., Malcolm E., West K., Rose D., London J., Rusch N., et al., “Influence of Time to Change's Social Marketing Interventions on Stigma in England 2009–2011,” British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 202 (suppl 55), 2013, pp. s77–s88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, J. I., “The Incorrect Use of Chi-Square Analysis for Paired Data,” Clinical and Experimental Immunology, Vol. 24, No. 1, 1976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm, Anthony F., Christensen Helen, and Griffiths Kathleen M., “The Impact of Beyondblue: The National Depression Initiative on the Australian Public's Recognition of Depression and Beliefs About Treatments,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 39, No. 4, 2005, pp. 248–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm, Anthony F., Christensen Helen, and Griffiths Kathleen M., “Changes in Depression Awareness and Attitudes in Australia: The Impact of Beyondblue: The National Depression Initiative,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2006, pp. 42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund P. A., Bruce M. L., Koch J. R., Laska E. M., Leaf P. J., et al., “The Prevalence and Correlates of Untreated Serious Mental Illness,” Health Services Research, Vol. 36, No. 6 (part 1), December 2001, pp. 987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, B. G., Phelan J. C., Bresnahan M., Stueve A., and Pescosolido B. A., “Public Conceptions of Mental Illness: Labels, Causes, Dangerousness, and Social Distance,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 89, 1999, pp. 1328–1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noar, Seth M., “A 10-Year Retrospective of Research in Health Mass Media Campaigns: Where Do We Go from Here?” Journal of Health Communication, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2006, pp. 21–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido, B. A., Monahan J., Link B. G., Steuve A., and Kikuzawa S., “The Public's View of the Competence, Dangerousness, and Need for Legal Coercion of Persons with Mental Health Problems,” American Journal of Public Health, Vol. 89, 1999, pp. 1339–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAND Corporation, “Statewide Prevention and Early Intervention Evaluation Strategic Plan,” California Mental Health Services Authority, November 9, 2012. As of April 17, 2015: http://calmhsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Statewide-PEI-Evaluation-Strategic-Plan-FINAL-rev2-11-09-12.pdf [Google Scholar]

- See Change, “Irish Attitudes Toward Mental Health Problems,” 2012. As of May 1, 2015: http://www.seechange.ie/wp-content/themes/seechange/images/stories/pdf/See_Change_Research_2012_Irish_attitudes_towards_mentl_health_problems.pdf

- Sharac, J., McCrone P., Clement S., and Thornicroft G., “The Economic Impact of Mental Health Stigma and Discrimination: A Systematic Review,” Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale, Vol. 19, 2010, pp. 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau, “State and County QuickFacts: California,” updated March 31, 2015. As of April 27, 2015: http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/06000.html

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General, Rockville, Md., 1999.

- Wang, P. S., Lane M., Olfson M., Pincus H. A., Wells W. B., and Kessler R. C., “Twelve-Month Use of Mental Health Services in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication,” Archives of General Psychiatry, Vol. 62, No. 6, June 2005, pp. 629–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie, Allan, and Lauder James, Impacts of National Media Campaign to Counter Stigma and Discrimination Associated with Mental Illness: Survey 12: Response to Fifth Phase of Campaign, Auckland, New Zealand: Phoenix Research, June 2012. [Google Scholar]