Abstract

Background

To send meaningful information to the brain, an inner ear cochlear implant (CI) must become closely coupled to as large and healthy a population of remaining Spiral Ganglion Neurons (SGN) as possible. Inner ear gangliogenesis depends on macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), a directionally attractant neurotrophic cytokine made by both Schwann and supporting cells (Bank et al., 2012). MIF-induced mouse embryonic stem cell (mESC)-derived “neurons” could potentially substitute for lost or damaged SGN. mESC-derived “Schwann cells” produce MIF as do all Schwann cells (Huang et al., 2002; Roth et al., 2007, 2008) and could attract SGN to “ cell coated” implant.

Results

Neuron- and Schwann cell-like cells were produced from a common population of mESC in an ultra-slow flow microfluidic device. As the populations interacted; “neurons” grew over the “Schwann cell” lawn and early events in myelination were documented. Blocking MIF on the Schwann cell side greatly reduced directional neurite outgrowth. MIF-expressing “Schwann cells” were used to “coat” a CI: mouse SGN and MIF-induced “neurons” grew directionally to the CI and to a wild type but not MIF-knock out Organ of Corti explant.

Conclusions

Two novel stem cell-based approaches for treating the problem of sensorineural hearing loss are described.

Keywords: inner ear-like neurons from stem cells, stem cell derived Schwann cells, microfluidics, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, neurotrophic cytokines, hearing

INTRODUCTION

Development of new stem cell-based therapeutic approaches is bringing the era of regenerative medicine into more immediate focus. For example, a current area of intense interest to neuroscientists and bioengineers is the potential replacement of lost or diseased central and peripheral neurons and/or peripheral nervous system Schwann cells with biologically engineered stem cells. Ideally, stem cells would be capable of taking on the mature properties of both neuronal and Schwann cell types and could also participate in the critical crosstalk that leads to myelination of the neurons by Schwann cells.

The inner ear’s spiral ganglion’s myelinated bipolar neurons (SGN) provide the conduit for sensory messages from peripheral sensory receptors of mechanosensory hair cells to the central neurons in auditory brain stem nuclei. When the hair cells in the Organ of Corti are lost or incapacitated, due to injury, ageing or loss of function resulting from genetic disorders, spiral ganglion neurons lose their peripheral targets and can progressively degenerate, so that the remaining neurons are less capable of functional interaction with either the remaining sensory Organ of Corti hair cells or with a cochlear implant/prosthesis (Pfingst et al., 2015, review). Although spiral ganglion neuron loss in humans is less pronounced than in animal models of hair cell loss or Knock out mouse models of hair cell loss (Bermingham-McDonogh and Rubel, 2003; Bodmer, 2008; Breuskin et al., 2008), it appears that even if spiral ganglion neurons remain as long as 40 years post onset of deafness, their functionality can be impaired (Sato et al., 2006; Wise et al., 2010),(Jiang et al., 2006).

In order to interact productively with a cochlear implant, the surviving spiral ganglion neurons must be healthy and sufficiently well-distributed along the cochlea to cover the range of frequency distribution required to deliver the necessary information for speech discrimination (Parkins, 1985). Although conductive hearing loss can be remediated by using hearing aids, middle ear implants and bone anchored hearing aids, a direct stimulation of the auditory nerve is required when sensorineural hearing loss is severe. Such stimulation can be achieved by implanting cochlear prostheses/implants in the scala tympani of the cochlea. However, in the future, direct auditory brain stem implants may well become the standard therapeutic approach (reviewed in Merkus et al, 2014).

Some very promising studies of hearing restoration have recently been done in mammalian animal models. Endogenous Supporting cells of the inner ear have been shown to differentiate and replace hair cell function (e.g. Mellado Lagarde et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2013; Monzack and Cunningham review, 2014). Human inner ear stem cells transplanted into deafened animal models also restored hearing function (Chen, Jongkamonwiwat et al., 2012).

Strategies for prolonging survival or regenerating spiral ganglion neurons, many focused on earlier-identified inner ear neurotrophins as inducing agents (Roehm and Hansen, 2005; Ramekers et al., 2012) have been a focus of research for many years. To restore hearing function and prolong survival of existing spiral ganglion neurons, some researchers have developed paradigms in which a single neurotrophin or a cocktail of neurotrophins was administered to deafened animals using mini osmotic pumps or via cochlear implants coated with various gels/hydrogels that can slowly release such neurotrophins (Winter et al., 2007; Jun et al., 2008; Winter et al., 2008; Jhaveri et al., 2009). However, such treatment options have not yet progressed to clinical or even pre-clinical trials in patients with hearing loss (Miller et al., 2002; Pettingill et al., 2007a, b; O’Leary et al., 2009b; Pfingst et al., 2015).

To improve the performance of cochlear implants, a variety of different strategies to improve hearing perception are being tested; among these are: 1. Advanced engineering of cochlear implant devices, which can communicate well with the brain stem (for a review see Pfingst et al., 2015), 2. Cell replacement therapies, involving various types of stem cells to augment or substitute for lost or malfunctioning neurons (Corrales et al, 2006; Coleman et al., 2007: Reyes et al., 2008; Chen, Jongkamonwiwat et al., 2012) 3. Re-growing spiral ganglion neuronal processes to improve connections with the implant and concomitantly to reduce the distance between them (Altschuler et al., 1999); 4. “Classical” neurotrophin-releasing Schwann cells used to ‘coat’ cochlear implants have been shown to enhance neurite contacts with the devices (O’Leary et al., 2009).

The research described in this report focuses on two stem cell-based strategies to address sensorineural hearing loss: Replacement of damaged or lost spiral ganglion neurons and neurotrophic factor-producing cells that could enhance the attractive properties of a cochlear implant. We used a very-slow-differential-flow microfluidic device (Park et al., 2009), to differentiate a common population of embryonic stem cells into two different types of cells—neuron-like cells and Schwann cell-like cells, using differential flow to deliver inducing agents for neurons and Schwann cells simultaneously in two streams of fluid, which, although side by side move at different flow rates.

When macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF)—and not nerve growth factor (NGF) or ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF)-- is the neuron-inducing agent, we show that the neuron-like cells bear some significant resemblance to statoacoustic ganglion or spiral ganglion neurons of the inner ear. NGF and CNTF also induce neuronal phenotypes; we have shown in other studies that NGF produces dorsal root ganglion-like neurons and CNTF induced motor neuron-like neurons (Roth et al., 2007, 2008; Bank et al., 2012). We have previously shown that MIF is the inner ear’s first developmentally important neurotrophin (Holmes et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2012; Bank et al., 2012, cited in Faculty of 1000) and that receptors for MIF remain on spiral ganglion neurons into adulthood (Bank et al, 2012). These earlier studies were done in conventional tissue culture devices/dishes.

In this study, the MIF-induced neuron-like cells produced on the “neuronal” differentiation side of the slow-flow microfluidic devices were characterized for electrophysiological functional maturation by patch clamping and for transporters, neurotransmitters and appropriate ion channel expression by immunocytochemistry and RTqPCR. The MIF-induced neuron-like cells’ properties were compared to the neuron-like cells induced with Nerve Growth Factor (NGF) or Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor (CNTF) as we had done previously in our conventional tissue culture studies (Roth et al., 2007, 2008; Bank et al., 2012). The neuron-like cells’ maturation is enhanced by exposure to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which is capable of enhancing both electrophysiological functional maturation (Uauy et al., 2001; Khedr et al., 2004) and myelination in the microfluidic device (Fig. 4).

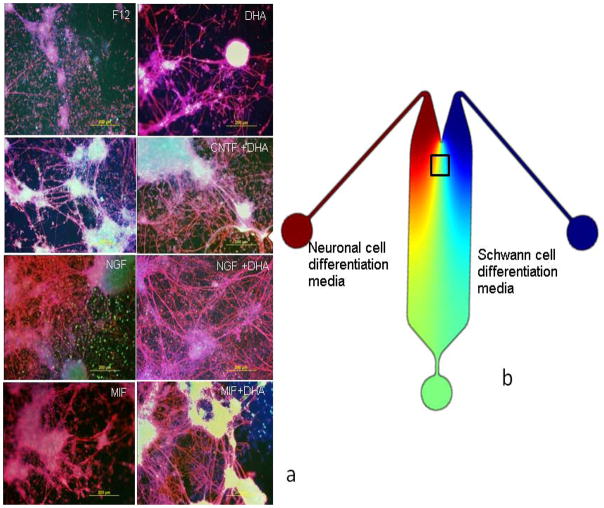

Figure 4.

Observations of myelination onset as neuron-like cells and Schwann cell-like cells interact in the mid-section of the Microfluidic device Row II. The cultures were stained for neurofilament Heavy 200 kDa (NF-H) (red), Myelin Basic Protein (blue) and VgluT1 (green). F12=the basal medium, CNTF=ciliary neurotrophic factor; NGF=nerve growth factor; MIF=macrophage migration inhibitory factor; DHA=docosahexaenoic acid (b) Merged images of multi-labelled devices (c) Cartoon showing the location of Row II, which is also shown Fig. 1.

Neuregulin (Gambarotta et al., 2013) was used to induce Schwann cell-like cells as in our previous studies (Roth et al., 2007, 2008) in the other fluid stream of the device. Our laboratory made the first embryonic stem cell-derived Schwann cells almost a decade ago (Roth et al., 2007). We demonstrated previously that these engineered Schwann cells have all the properties of myelinating Schwann cells (Roth et al., 2007), acquire Schwann cell-like properties in the expected order during maturation and that they produce MIF as do all vertebrate Schwann cells (Huang et al., 2002).

Such stem cell-derived neuron-like and Schwann cell-like cells could be used independently or together to provide therapeutic approaches to alleviate a variety of neurological disorders, including multiple sclerosis (Taupin, 2011; Zhang et al., 2011) spinal cord injury (Paino et al., 1994; Goodman et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2007;Boomkamp et al., 2012); Parkinsonism (Mena and Garcia de Yebenes, 2008); peripheral nerve regeneration (Namqung et al., 2015) and, most importantly for these studies, sensorineural hearing loss/deafness (Pettingill et al., 2008). Replacement of the sensory hair cell population from stem cells endogenous to the inner ear is also under investigation (Li et al., 2003a,b; Liu et al, 2014) although not in these studies.

It has been difficult to study the stages of neuron-Schwann cell interactions that result in myelination in conventional tissue cultures of primary peripheral system neurons and Schwann cells (Gingras et al., 2008; Heinen et al., 2008; Callizot et al., 2011; Jarjour et al., 2012) for several reasons: 1) the inability to distinguish living primary neurons from Schwann cells in conventional cell co-cultures during the differentiation and interaction process (Paivalainen et al., 2008), unless one population or the other is tagged with a live cell label; 2) the difficulty in obtaining immature cultures of both primary neurons and Schwann cells in order to observe and document the key EARLY steps in their interactions that lead to myelination and 3) sufficiently specific stage-specific markers of myelination progress, as our earlier studies documented (Roth et al., 2007, 2008).

Tissue engineered co-culture systems have been somewhat successful in identifying key molecular steps and markers in studies of myelination (Hsu and Ni, 2009; Liazoghli et al., 2012). A number of such co-culture systems have involved variously derived stem cells (Yang et al., 2008: Wei et al., 2010; Xiong et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012) mostly to provide the “neuronal” component. However, none of these engineered stem cell based systems has been sufficient to observe the continuum of cell-cell interactions that result in early events in myelination.

The very slow-flow devices used in these studies allows us to study neuronal/Schwann cell interactions that result in onset of myelination during the course of the experiment, which can be carried out for up to 6 weeks. An osmotic pump is essential to achieving sufficiently slow flow with low shear that does not cause cell detachment and that allows us to culture cells in devices with nutrient replenishment and eliminate wastes for up to 6 weeks.

The device was designed to generate overlapping gradients of one of the neurotrophic factors (MIF, NGF or CNTF; Bank et al., 2012) as well as Schwann cell-inducing factors (Neuregulin; Roth et al., 2007) from two different inlets (see cartoon in Fig. 1). By stably maintaining flow over a 3–6 week period, we were able to correlate cell differentiation and neuronal outgrowth to computed concentrations of the different factors and to document many aspects of the interactions between the two cell types in the device—particularly the very early events in myelination. The microfluidic device allows us to study the cell-cell interactions between the “neurons” and the “Schwann cells” with time-lapse digital cinematography and also permits molecular, immunohistological and electrophysiological analyses of the cells in the device itself.

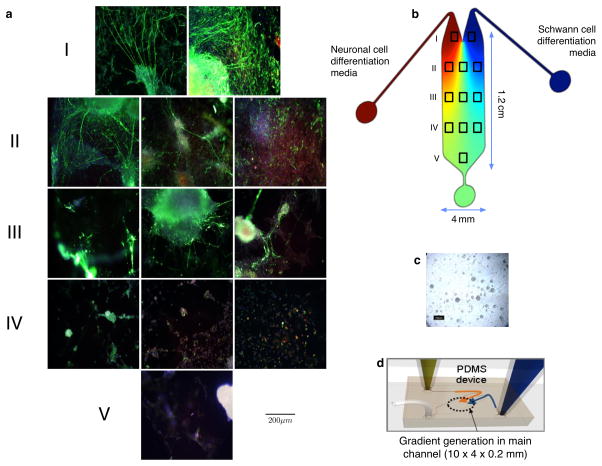

Figure 1.

The mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) seeded on the device differentiated into both neuron-like and Schwann cell-like cells.. (a) Photomigrographs of the areas of the device depicted as boxes in the cartoon in (b) were taken after the whole device was stained for neurofilament 150 kDa – neurites (green); Dapi-nucleus (blue); Myelin Basic Protein – evidence of Schwann cell myelination (red). After 3 weeks, the top three rows (I, II, III) show significant neuronal differentiation as well as directional outgrowth of neurites (green) towards the “Schwann cell” sectors (those on the right). In the bottom two rows (those with the most media intermixing and least preserved gradients), the cells apparently did not differentiate into any specific lineage (IV and V). The white arrows in (a) indicate the directional outgrowth of neurites. (c) Undifferentiated mES cells in the microfluidic device. (d) A cartoon of the microfluidic device. The gradient flow illustration (b) and microfluidic chip channel dimensions depicted in (d) are adapted from (Park et al., 2009).

The role of MIF produced by the “Schwann cells” in promoting directional outgrowth of processes from the “neurons” towards the Schwann cell side of the device was tested in two ways. After the embryonic stem cells had differentiated into “Schwann cells” or “neurons” we blocked MIF production on the Schwann cell side of the device with the biochemical MIF inhibitor, 4-iodo-6-phenylpyrimidine (4-IPP; Specs, Delft, Netherlands) at 0.1 μM 4-IPP for 7 days, as we have done previously (Shen et al., 2012). In another set of experiments, we blocked MIF downstream pathways with a monoclonal antibody to MIF using conditions we previously established for studies of both mouse and chick cultured primary neurons and stem cell derived neurons (Bank et al., 2012). Blocking MIF resulted in a significant reduction in directional neurite outgrowth towards the “Schwann cell” lawn in the microfluidic devices (Fig. 2), just as we previously demonstrated in conventional tissue culture experiments (Bank et al., 2012).

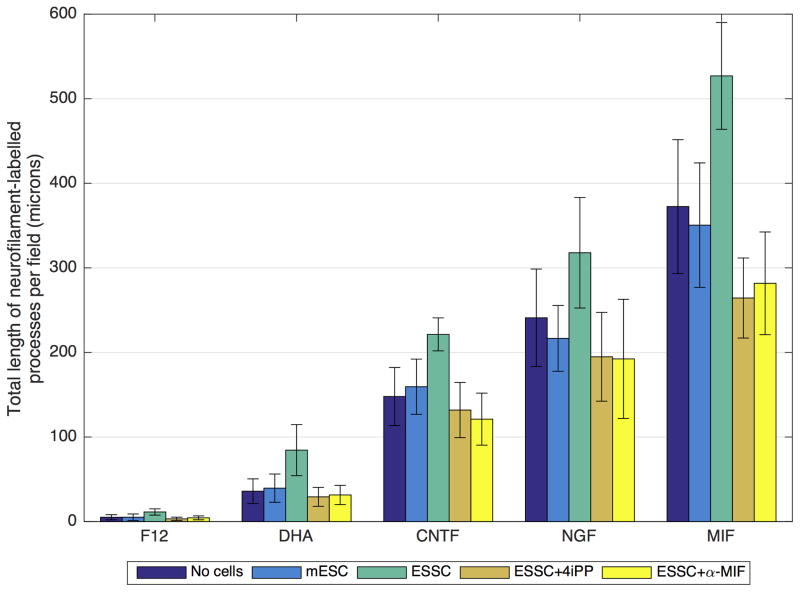

Figure 2.

Neurite measurements of the neuron-like cells differentiated with different neurotrophic factors with and without DHA in the microfluidic device. The “neurites” of neuron-like cells cocultured with Schwann cell-like cells in the microfluidic device grew directionally towards and over the “Schwann cell” lawn. Total process lengths were measured using MetaMorph® or ImageJ software for this directional outgrowth; 8 experiments using a minimum of 10 photographed fields of view in each were used. mESC = undifferentiated mouse embryonic (D3) stem cells on the “Schwann cell” side of the device. ESSC = Embryonic Stem cell-derived Schwann cells; these are Neuregulin-induced “Schwann cells” derived from the mESC. ESSC +4iPP: under these conditions, the differentiated “Schwann cell lawns on the Schwann cell side of the device were treated with the biochemical MIF inhibitor 4iPP (as described in Methods and in Shen et al., 2012). ESSC+ α-MIF: Downstream MIF effects were blocked by addition of a function-blocking anti-MIF antibody (α-MIF) as we had done in previous studies (Bank et al., 2012).

Significance Calculations for these data

Differences between treatment groups and statistical significance were analyzed using Mann-Whitney U tests performed in Matlab. There were statistically significant differences found amongst these treatment groups with p values as indicated below:

DHA alone: (mESC vs ESSC, p =0.0023; ESSC+4iPP vs ESSC, p = 3.1080 ×10−4; ESSC+ α-MIF vs ESSC, p = 5.4390 ×10−4)

CNTF alone: (mESC vs ESSC, p =1.5540 ×10−4; ESSC+4iPP vs ESSC, p =7.7700 ×10−5; ESSC+ α-MIF vs ESSC, p = 7.7700 ×10−5)

NGF alone: (mESC vs ESSC, p =0.0050; ESSC+4iPP vs ESSC, p =0.0015; ESSC+ α-MIF vs ESSC, p = 0.0052)

MIF alone: (mESC vs ESSC, p =5.4390 ×10−4; ESSC+4iPP vs ESSC, p = 7.7700 ×10−5; ESSC+ α-MIF vs ESSC, p = 7.7700 ×10−5)

Once we had convincing data confirming our earlier studies that MIF appears to be involved in directional neurite outgrowth either through its direct effects (see fig. 1 in Bank et al., 2012) or through its production by an mESC-derived “Schwann cell” lawn (see fig. 5B in Roth et al., 2007), we used the MIF-producing mouse embryonic stem cell-derived Schwann cells, encapsulated in sodium algenate hydrogels, to coat two types of cochlear implants: the multi-electrode type commonly used in human patients and the simple ball type used in animal studies.

Directional outgrowth of neurites from primary mouse statoacoustic ganglion (which is the embryonic precursor of both the spiral ganglion and vestibular ganglion in the vertebrates that develop both SG and VG) and spiral ganglion explants extending neurites toward the devices was observed by time-lapse cinematography. Contacts with the implants were visualized by immunocytochemistry using specific markers.

MIF-induced neuron-like cells were also co-cultured with mouse Organ of Corti explants and directional outgrowth of neurites towards the target was documented towards wild type but not the MIF-knock out Organ of Corti explants. We had already demonstrated that this could be done with primary neurons in conventional tissue culture (Bank et al., 2012).

This study could eventually benefit two types of patients—1) those with low spiral ganglion neuron counts who are not good candidates for cochlear implant therapy, for whom a replacement population of stem cell derived neuron-like exogenous cells could enhance functional contacts with their own native Organ of Corti sensory hair cells and 2) patients for whom cochlear implants coated with MIF-producing Schwann cell-like cells could markedly improve directional outgrowth of their remaining spiral ganglion neurites to the cochlear implant.

RESULTS

Concomitant differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) into neuron-like cells and Schwann cell-like cells in a slow flow microfluidic device

We differentiated mouse embryonic stem cells into both neuron-like cells and Schwann cell-like cells in the same microfluidic device to study cell differentiation and maturation (neuronal or Schwann cell) as well as any cell-cell interactions between the Schwann cells and the neurites emerging from the neuron-like cells; e.g. those that might result in evidence of myelination upon contact with the Schwann cell-like cells.

The microfluidic system was designed to establish a gradient flow to nourish the stem cells with nutrients and growth factors or neurotrophic cytokines in order to facilitate the differentiation of two different cell populations from a single undifferentiated stem cell population seeded on the device. Figure 1c is a bright-field image of undifferentiated mouse embryonic stem cells (ESC; Doetschman et al., 1985) seeded over the entire surface area of the device after coating the device with sterile porcine gel (see Experimental Procedures). A cartoon of the device, with the “neuron” side depicted in red and the “Schwann cell” side depicted in blue is seen in Fig. 1b. Then, using differential flow, Schwann cell-like cells were induced to form on the right half of the device (blue outflow source seen in the cartoon in Figs. 1b and 1d) using concentrations of Neuregulin that we had previously determined produced myelinating Schwann cells (Roth, Ramamurthy et al., 2007, 2008).

One of 3 different inducing agents was used to produce the neuron-like cells in the left (red Fig. 1b) half of the device: NGF, CNTF or MIF at concentrations we had previously optimized (Roth et al., 2007, 2008; Bank et al., 2012; see Experimental Methods). The “neuron”-inducing agent was delivered form the reservoir indicated in red in the cartoon in Figs. 1b and 1d. DHA enhancement was also tested in the microfluidic devices in some cases and it was delivered through the same portal. DHA enhancement had proven to be very effective in our previous studies, even at the lowest concentration we tested (Bank et al., 2012). Three to 8 duplicate devices for each inducing agent or condition were prepared in parallel, incubated, fixed, labelled (e.g. with antibodies to Neurofilament or TUJ1), photographed and analyzed for each set of conditions using MetaMorph© software.

After one week in the microfluidic devices, we saw both morphological and molecular evidence of neuronal differentiation on the “neuronal” side of the device under all neuron-inducing conditions at the concentrations tested (see experimental methods), including DHA alone. Neurofilament-positive cell bodies with extensive processes were documented photographically and analyzed by MetaMorph© or NIH ImageJ software. By contrast, little if any neuronal differentiation was seen at 1 week in the presence of F12 medium alone (control) (Fig. 2), as we had also previously documented (Roth, Ramamurthy et al., 2007, 2008; Bank et al., 2012).

After 2–3 weeks, we observed that more than 75% of the mES cells exhibited neuronal processes in response to NGF, CNTF or MIF as well as to any of these inducing agents enhanced with DHA. However, because the “neuron-like” cells were clumped together and the processes were found in fascicular bundles (e.g. Bank et al., 2012, Fig. 2), it was often difficult to determine the actual numbers of neuron-like cell bodies in the clumps or how many processes were present in the fascicles. Fasciculation was enhanced markedly by the addition of DHA.

Directional Neurite Outgrowth is observed from the Neuron-like cells towards the “Schwann cell” sectors in Microfluidic Devices

To determine if there was preferential neurite outgrowth from the neuron-like cells toward the Schwann cell-like cells in the microfluidic device (Fig. 1a), we used time-lapse videomicrography and end-stage photomicrography to identify immuno-labelled (neurofilament or TUJ1) cells and processes on the “Schwann cell” side of the devices. Photographs of the immuno-labelled cells were analyzed by MetaMorph© or NIH ImageJ software. For these analyses, we virtually sectioned the device into 5 rows (I, II, III, IV, V; Figs. 1a and 1b). Rows II, III and IV were divided into three columns for taking the photomicrographs used in these analyses (see the cartoon in Fig. 1b). The mouse embryonic stem cells showed concentration-dependent differentiation from the channel inlet to the outflow port (depicted in the cartoon in (Fig. 1b) as a round green area at the bottom. ES cells took on neuronal morphologies in areas closest to the left inlet (Fig 1a: I, II). The cells that became neuron-like in sectors I, II and any found in III extended neurites toward the Schwann-cell like cell lawns (e.g. Fig. 1a Row I right image), since Schwann cell-like cells produce MIF, which is both a neurite outgrowth and survival factor for many different neuronal subtypes, including those in the inner ear (Bank et al., 2012) and eye (Ito et al., 2008). We tested the role of MIF directly in additional studies (Fig. 2 below). The extension of ramifying processes of the neuron-like cells over the Schwann cell lawn is also typical of the behaviour of primary neurons on such engineered Schwann cell lawns (see Roth et al., 2007 fig. 5b). Neurofilament positive neuron-like cells that differentiated in Row III (Fig. 1 a: III middle) had minimal numbers of neuronal processes; however, the few processes that were present grew directionally towards the Schwann cell lawn (blue side of the device Figs. 1a,b). Neuron-like cells in row IV also could be labelled for neurofilament but no processes developed in this region (Fig. 1a IV). There were cells in row IV that were not stained for neurofilament (Fig. 1a) but could be stained for myelin basic protein MBP, indicating that they were “Schwann cells” (see also Fig. 4) (as in our previous work, Roth et al., 2008). Cells in region V did not express markers for either Schwann cells or neurons; nor was there evidence of myelination, indicating the undifferentiated ES status of these cells, many of which still expressed Oct4 (Roth et al., 2007 2008; Bank et al., 2012), a marker for undifferentiated stem cells (Pan et al., 2002). The gradient profile created in the device, in which the highest concentrations of neuron-inducing and Schwann cell-inducing media predominated near the inlets facilitates ES cells’ ‘differentiation into neuron-like cells and Schwann cell-like cells with a much higher expression level of their cell type specific protein markers (Fig. 1a I, II, III). Neurites extending over the Schwann cell lawn in row I (Fig. 1a I right) also exhibited the most neurite fasciculation compared with the other sections of the device. We observed cell differentiation by both time-lapse cinematography and end-stage photomicrography. We measured the total neurite outgrowth of the processes using confocal microscopy and light photomicrography, analyzed by MetaMorph© software or NIH ImageJ software (Experimental Procedures).

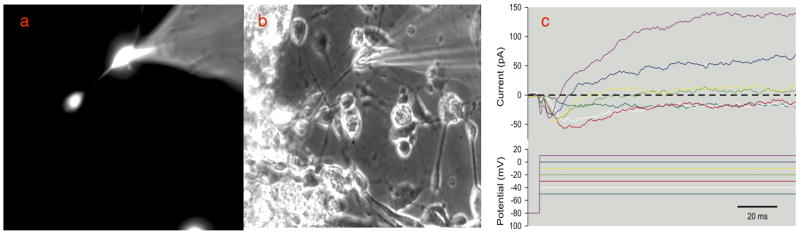

Figure 5.

Patch clamp studies performed on the neuron-like cells induced by MIF. a. Electrodes were filled with ionic fluorescent rhodamine dye and used to patch clamp the cell membrane of cells identified as having a neuronal morphology. b. Phase contrast image of a group of differentiated neuron-like cells; the cells that were identified as having a bipolar neuronal morphology were patch-clamped using a fire polished glass pipette electrode. MIF- and DHA-treated ES cells showed voltage dependent inward and outward current with long active response times, demonstrating voltage-dependent currents in a neuron-like bipolar cell. Voltage dependent changes were seen in response to step depolarization from a holding potential of −80 mV. Both transient inward currents and maintained outward currents were observed. The linear leak currents and most of the linear capacity currents were removed during data acquisition with a P/8 protocol (although a small residual capacity transient is visible immediately after the voltage steps). The ionic conditions were set so that ENa and EK were at normal levels and neither sodium nor potassium channels were blocked, so the responses to small voltage steps are dominated by transient inward sodium currents that got faster as the cell was depolarized, and the response to large steps was dominated by a maintained outward current.

MIF production by Schwann cell-like cells appears to play a role in directional process outgrowth

When devices were stained with an antibody to Neurofilament and appropriate secondary antibodies, little or no directional outgrowth towards the “Schwann cell” side of the device was seen under any of the “neuron-inducing” conditions (Fig. 2) if there were no cells on the “Schwann cell” side of the device. This was also the case if there were undifferentiated mESC (not exposed to Neuregulin) on the “Schwann cell” side. However, if Neuregulin had been used to induce a Schwann cell-like phenotype, there was a significant directional process outgrowth towards the Schwann cell lawns (Fig. 2). Compare the process outgrowth towards the undifferentiated mouse embryonic stem cell lawns [mESC] with outgrowth towards mESC induced to become Schwann cell like with Neuregulin [ESSC] (Fig. 2). mES Schwann cell differentiation resulted in ramification of “neuron-like” processes over the Schwann cell lawns, no matter which neuronal inducing agent was used on the “neuron” side (see also Fig. 5B Roth et al., 2007). However, more extensive process outgrowth and more extensive fasciculation were seen if the inducing agent was MIF (Fig. 2), and the difference was significant (compare the statistics for the various neurotrophic inducing agents included in the caption to Fig. 2).

As we had demonstrated in our previous studies (Roth, Ramamurthy et al., 2007; Bank et al., 2012), MIF production by the differentiated Schwann cell like cells induced by Neuregulin appears to provide a major impetus for this process extension, whether by primary neurons (Fig. 5B, Roth et al., 2007) or stem cell-derived “neurons” (Fig. 2). We examined this directly by blocking MIF downstream effects in one of two ways: 1) The biochemical MIF inhibitor, 4-iodo-6-phenylpyrimidine (4-IPP; Specs, Delft, Netherlands), at a final concentration of 0.1 μM, was used as described previously (Shen et al., 2012) or 2) a MIF function-blocking monoclonal antibody, also used as described previously (Bank et al., 2012). These MIF blocking strategies were used ONLY on the Schwann cell side of the device (seen in Blue in the cartoon in Fig. 1) once the both cell types (“neuron-like and “Schwann cell-like”) had phenotypically differentiated. Use of either means of inhibiting MIF downstream effects reduced the extent of “neurite” outgrowth over the “Schwann cell” lawns to levels seen when either no cells or undifferentiated mESC (no Neuregulin) were plated on the “Schwann cell” side of the device. This difference was particularly significant for the MIF-induced “neurons” (Fig. 2; significance calculations below in the caption).

In summary, for “neurons” induced by DHA alone and by each neurotrophin (CNTF, NGF and MIF) the ES SC condition has a significantly higher mean value for directional neurite outgrowth than the mESC, ES SC+4iPP, and α-MIF conditions. This is not surprising since all Schwann cells are known to produce MIF (Huang et al., 2002a,b; Nishio et al., 2002; Bank et al., 2002) as well as another neurotrophic cytokine, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (Bianchi et al., 2005; Roth et al., 2007, 2008; Bank et al., 2012). Furthermore, vertebrate statoacoustic ganglion neurons, spiral ganglion neurons and MIF-induced stem cell derived neurons are known to express MIF receptors (Shen et al., 2012; Bank et al., 2012) and to continue to express these receptors into adulthood (Bank et al., 2012). We have shown that MIF is a directional neurite outgrowth factor for many neuronal subtypes, particularly those in the inner ear (Roth, Ramamurthy et al., 2007). We have also shown that it is a neuronal survival factor (Bank et al., 2012).

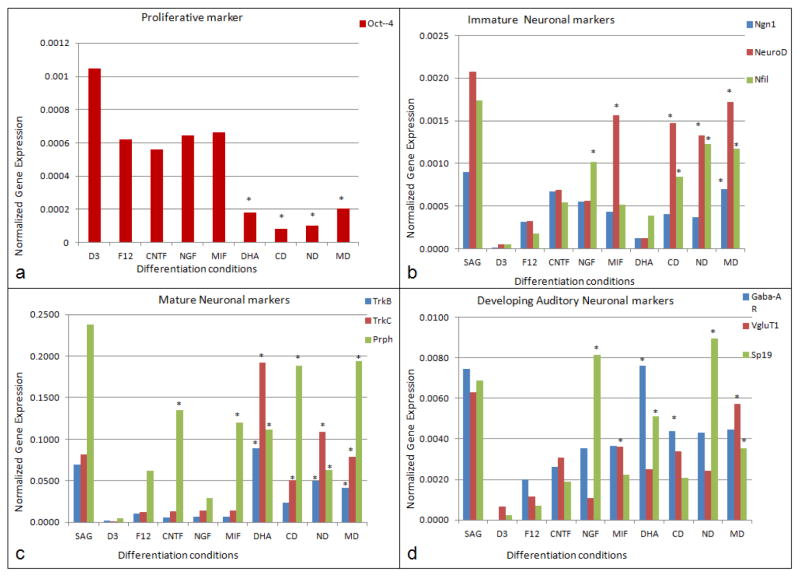

Neuron-like cells in the microfluidic devices develop neuronal characteristics as assessed by appearance of neuronal markers measured with RTqPCR

Analysis of neuronal differentiation using primer pairs (Table 1) for neuronal markers and for undifferentiated ES cells (Oct4 expression; Pan et al., 2002) was done by RTqPCR as in our previous studies (Roth et al., 2007; Roth et al., 2008; Bank et al., 2012). Oct4 remained at high expression levels under proliferative conditions (no neuronal differentiation media added) and was down-regulated under differentiation conditions (Fig. 3a). Cells treated with cytokines or neurotrophins alone showed a 2-fold down-regulation of Oct4 gene expression and cells treated with DHA as well as MIF and/or neurotrophins showed a four-fold Oct4 down-regulation when compared with the undifferentiated conditions (Fig. 3a).

Table 1.

Primer Pairs for Assessing General and Inner Ear Specific Neuronal Differentiation

| Undifferentiated Cell marker | OCT4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Early stage neuronal markers | Neurogenin1(Ngn1) | GAGCCGGCTGACAATACAAT | AAAGTACCCTCCAGTCCAG |

| NeuroD | AGGCTCCAGGGTTATGAGAT | TGTTCCTCGTCCTGAGAACT | |

| Neurofilament | GGAATTCGCCAGTTTCCTGA | GCAAGGTTCTCCCATGAACA | |

| Mature neuronal markers | Neurotrophicc tyrosine kinase receptor type 2 (Trkb) | ACCATAAACCACGGCATGAG | CCGTGAAGCAGAGTTCAACA |

| Neurotrophicc tyrosine kinase receptor type 3 (Trkc) | AACCATCACGAGAAAGCCTG | ACCATCTCCACCTCTGCTTA | |

| Peripherin Prph | TCGACAGCTGAAGGAAGAGA | AGAGGCAAAGGAATGAACCG | |

| Auditory neuronal markers | Gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor (GABA-AR) | TCATCCTCAACGCCATGAAC | TCACCTCTCTGCTGTCTTGA |

| Vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VgluT1) | CCAAGCTCATGAACCCTGTT | ACCTTGCTGATCTCAAAGCC | |

| Voltage gated sodium ion channel (SP19 orNAV1.1) | CCATGATGGTGGAAACGGAT | AGATGAGCTTGAGCACACAC |

Figure 3.

RTqPCR quantification of gene marker expression in the differentiated neuron-like cells (a). OCT4 expression in undifferentiated mES cells and neuron-like cells differentiated from mES cells. D3: Undifferentiated condition, statoacoustic ganglion: (SAG) spiral ganglion neuron culture (control). (b). Expression of proneural marker genes in neuron-like cells cells. Ngn1, NeuroD and Nfil expression is much higher in neuronally differentiated cells, but not detected in undifferentiated condition (D3ES). (c). Expression of mature neuronal marker genes: TrkB, TrkC, Prph in the neuron-like cells are upregulated in all the neuronal differentiated conditions and expression levels are much higher under conditions with DHA addition. F12: Neuronal basal media, C: CNTF differentiation condition, N: NGF differentiation condition, M: MIF differentiation condition, D: DHA differentiation condition, CD: CNTF+DHA differentiation condition, ND: NGF+DHA differentiation condition, MD: MIF+DHA differentiation condition. (d). Expression of auditory neuronal markers, GabaAR, VgluT1 and SP19 are highly upregulated in the neuronal differentiation conditions compared to undifferentiated conditions and F12 (basal) medium. VgluT1 expression is much higher in the MIF+DHA condition than all the other differentiation conditions, which was to be expected, given that MIF is the inner ear’s first differentiation “neurotrophin” (Holmes et al., 2011; Bank et al. 2012; Shen et al., 2012).

In general, neurotrophins (Flores-Otero et al. 2007; Bank et al., 2012) are thought to provide molecular signals that mediate the survival of neurons. In mice, ganglion neuron precursors and developing cochlear neurons express the proneural gene Ngn-1. NeuroD and neurofilament (Nfil) are upregulated early in inner ear development (Flores-Otero et al. 2007; Nayagam et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2011; Shibata et al., 2011: Reyes et al., 2008). In spiral ganglion neurons, three different forms of Nfil are expressed sequentially (Nayagam et al., 2011;Yang et al., 2011). In these studies, we found Ngn-1 expression was upregulated under all neuronal differentiation conditions when compared with cells grown in F12 basal media (undifferentiated conditions) (Fig. 3b). Expression of NeuroD was upregulated in cells treated with MIF alone, with CNTF+DHA, NGF+DHA and MIF+DHA (Fig. 3b). A rise in NeuroD expression levels suggests that MIF alone without DHA could support the differentiation and survival of stem cell-derived-neurons. CNTF, MIF, CNTF+DHA, NGF+DHA, MIF+DHA significantly increased NeuroD expression when compared with mES cells grown in the F12 basal medium.

Neurofilament (Nfil) expression was upregulated significantly under all the differentiation conditions compared with F12 basal medium. Nfil expression was upregulated in cells treated with CNTF+DHA, NGF+DHA and MIF+DHA when compared with conditions without DHA (Fig. 3b). Proneural gene marker upregulation in cells treated with MIF alone and MIF+DHA suggests that the cells’ expression profile is consistent with what can be expected of expression in statoacoustic ganglion neurons (the spiral ganglion neuronal precursors) (Fig. 3b).

A number of transcription factors (GATA3, Brn3a, Ngn1, NeuroD, islet1) as well as receptors for neurotrophins (TrkB and TrkC) have been defined as mature markers for differentiating auditory and vestibular neurons (Nayagam et al., 2011; Shibata et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2011). Peripherin is also expressed concomitantly with axonal growth during development in the inner ear, and its synthesis appears necessary for axonal regeneration in the adult (Nayagam et al., 2011; Shibata et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2011). TrkB, TrkC and Prphn were significantly upregulated under conditions of DHA supplementation of either of the two neurotrophins or MIF (Nayagam et al., 2011; Shibata et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2011). Upregulation of these “mature” neuronal markers and some selected auditory system neuronal markers are seen in Figs. 3c and 3d.

Differentiated neuron-like cells were stained for VgluT1 (a marker for spiral ganglion neurons of the inner ear), Neurofilament 200 (a neuronal marker) and myelin basic protein (MBP), which labels mature, neuron-interactive myelinating Schwann cells (Roth et al., 2007, 2008) (Fig. 1, Fig. 3). Differentiation conditions under which cells were treated with NGF, CNTF or MIF, either of the neurotrophins+DHA, or MIF+DHA exhibited more extensive neurite outgrowth than was seen in the F12 Basal medium. Differentiation conditions with neurotrophins or with MIF supplemented with DHA have extensive fasciculated bundles of neurites, which were positive for the glutamate transporter, VgluT1 and neurofilament (Nfil200kDa). By contrast, few neurites stained for both VgluT1 and Nfil200 under conditions in which CNTF, NGF, MIF or DHA alone were used as the inducing agents. All the differentiated neuron-like cells in the mid region of the device showed healthy neurite outgrowth over the lawn of Schwann cell-like cells as did cells treated with CNTF+DHA, NGF+DHA and MIF+DHA (see Fig. 2 for total neurite outgrowth measurements).

A substantial increase in glutamatergic properties (e.g. increased VgluT staining of neurites), robust neurite outgrowth with multiple branches as well as evidence of myelination in the device were all found in MIF-induced neuron-like cells. Although these properties do not exclusively define spiral ganglion neurons, development of these properties indicates that the cells were developing at least some of the properties of spiral ganglion neurons. Such criteria would be critical if the “neuronal” population were to prove adequate substitutes for lost or diseased spiral ganglion neurons in vivo.

Evidence of Early Steps in Myelination is seen in the Microfluidic Devices in CNTF and MIF-derived “neurons”

If NGF was used as the inducing agent, little evidence of myelination was seen during the time course of these experiments (up to 30 days), even in the presence of DHA (NGF+DHA: Fig 4 or the presence of Schwann cell-like cells. However, neuron-like cells induced by CNTF showed evidence of myelination with and without DHA in the presence of Schwann cell-like cells. When neuron-like cells were induced with the neurotrophic cytokine, MIF, the presence of DHA greatly enhanced evidence of myelination in the presence of the Schwann cell-like cells (Fig. 4).

The process of myelination is extremely difficult to follow at the cellular level in its entirely in (approximately) real time in vivo, without sacrificing large numbers of animals. Even in vitro, using primary cell cultures of neurons and Schwann cells, the process is difficult to observe (Callizot et al, 2011). However, in the microfluidic device, we have created a microenvironment in which the cells can be differentiated concomitantly into the two lineages. We can now begin to study the interaction between the two cell types by time lapse video and by stage-specific immuno-labelling (Roth et al., 2007) as they mature and mutually influence the other population’s development, as happens in vivo (Salzer, 2012, 2015; Glenn and Talbot, 2013; Kidd et al., 2013). Schwann cell myelin production requires the influence of neurons capable of carrying on the complex sequence of required cell-cell interactions and molecular cross talk (Bodhireddy et al., 1994; Roth et al., 2007; Salzer, 2012, 2015). We had previously found evidence of early steps in myelination in interactions between primary inner ear statoacoustic ganglion neurons and a “Schwann cell” lawn produced by inducing the Schwann cell phenotype in embryonic stem cells (Roth et al., 2008).

Importantly, the slow flow feature of our device, which closely approximates interstitial flow with respect to diffusion strength, is physiological for neuronal cells. Neurons usually develop in and remain separated from high flow rate environments (blood flow or even lymphatic flow in the body), which at least for the CNS, where oligodendrocytes and not Schwann cells myelinate neurons, is maintained by the blood-brain barrier. It is important to note that even in such flow-free environments, neurons still require a replenished nutrient supply and waste clearing by minimal convective flow, which is also achieved in our slow flow device. Stability of the flow in the channel is guaranteed since the operation of the flow is based simply on osmosis, a very stable phenomenon. The overall pattern of the two differentiated cell types in the device suggests that the neuron-like cells grown with the Schwann cell-like cells exhibited directional outgrowth towards the Schwann cell-like target cells (e.g. Fig. 1a Row 1 right). This observation recapitulates our earlier finding that neurites from primary ganglionic explants similarly ramify over such a stem cell-derived Schwann cell lawn (Roth et al., 2007). There is ample evidence of the early stages of myelination (Fig. 4) as these differentiating “neurons” and “Schwann cells” interact.

Properties of neuron-like cells differentiated by MIF or MIF+DHA could lend themselves to replacement strategies for inner ear neurons

We used whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiological recordings to determine whether the neuron-like cells derived from mES cells induced with MIF had excitable properties that showed voltage gated inward and outward currents. This would be the minimum requirement for action potentials and therefore render these cells capable of encoding frequency information from a cochlear implant electrode and conveying it to the central nervous system (CNS). After 3 weeks, an excitable population of neuron-like cells was identified in the 80% of cells that had taken on a neuronal morphology. The population with measurable excitable properties was approximately 25% of the cells with a neuronal morphology. By contrast, if the mESC were exposed to the F12 basal medium without any differentiation factors, no such properties could be documented.

To explore the underlying cause of these electrophysiological changes, we investigated the voltage-dependent properties of Na+ and K+ currents using whole-cell voltage-clamp electrophysiology. We detected voltage dependent inward and outward current with long active response times in the MIF/DHA exposed “neurons” (Fig. 5c) whereas the cells in F12 media alone (basal medium) showed no neuronal morphology and no active responses or any inward or outward currents. Electrophysiological recordings were also made in the NGF+DHA condition. However, no inward or outward currents were found. We also labelled the MIF and/or DHA-induced neuron-like cells for ion channel protein expression with antibodies for sodium ion channel SP19 and potassium ion channel Kv3.1 on the same cell preparation (double labeling). SP19 was distributed all over the somas and along the neurites, as well intra-cellularly (potentially nuclear staining); Kv3.1 was also expressed in the cell body and along the processes, although the staining was less well defined (data not shown). This finding does, however, agree with our RTqPCR data (see Table 1).

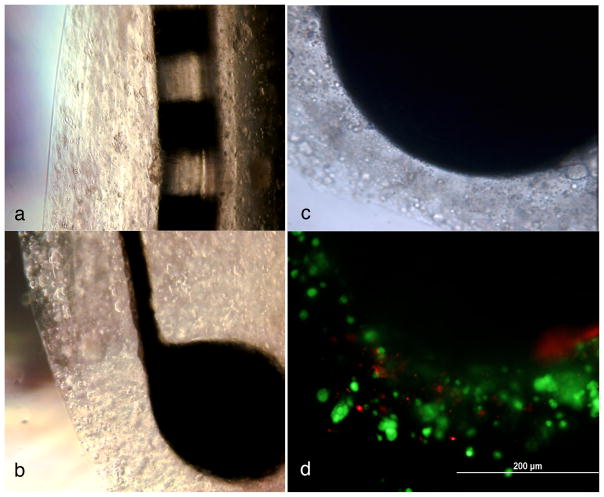

Coating of SC cells on Cochlear implants using hydrogel layering

We were sufficiently encouraged by the preliminary analyses of MIF-neuron-like cells that showed these cells had features that could potentially serve in the place of spiral ganglion neurons, to proceed to “coating” CIs with MIF-producing Schwann cell-like cells. We then followed the interaction of the MIF-induced neuron-like cells with these “coated” implants in vitro. Earlier work by Shepherd’s group (Pettingill et al., 2007) had demonstrated that CIs could be coated with neurotrophin-expressing Schwann cells that would attract SGN.

Two different types of platinum iridium electrodes (kindly provided by Dr. Bryan Pfingst, Dept. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, University of Michigan) were “coated” with Schwann cell-like cells or undifferentiated mESC using 1% sodium alginate hydrogel as a scaffold; both types of coated CIs were grown in culture for two weeks (Fig. 6). The cultures were supplemented with fresh media every week. Control electrodes were either uncoated, coated in hydrogel layers without cell inclusions or coated with undifferentiated mESC in the hydrogel layers. Fig. 6a is a photograph of a cochlear implant of the type used in human patients, coated with Schwann cell-like cells in the hydrogel layers (5 layers are readily discerned in this photograph). Figs. 6b through 6d are photographs of the type of cochlear implant electrode used in animal studies. All are photographs of the same electrode. Five layers of hydrogel containing Schwann cell-like cells are seen in Fig. 5b. Fig. 5c, is a close up phase contrast photograph of the electrode ball head. The encapsulated cells were stained for live and dead cells with ethidium bromide and calcein (LIVE/DEAD® Cell Viability Assays, Invitrogen, CA). Large numbers of healthy cells (green) and very few dead cells (orange) were found in the hydrogel layers coated with the Schwann cell-like cells (Fig. 6c) or undifferentiated ES cells (control; not shown) at 6 weeks in culture.

Figure 6.

Two types of cochlear implants coated with hydrogels with encapsulated Schwann cell-like cells: a. Platinum iridium eight array electrode of the type used in human patients. b. Platinum iridium electrode with a ball at the end of the type used in animal studies The differentiated Schwann cell-like cells were grown in layers on the electrodes in sodium alginate hydrogels for 2 weeks; Healthy Schwann cell-like cells are visible in 5–6 layers on both cochlear implants (a) and (b). (c) Higher magnification phase contrast imge of the hydrogel layers on a ball implant. (d) Fluorescence micrograph of the same cochlear impant pictured in (c). Live/Dead staining was used to distinguish living from dead cells. Ethidium homodimer was used to stain dead cells- (orange) and calcein AM was used to stain the live cells (green). The implant was coated with hydrogel-encapsulated Schwann cells, which were maintained for 2 weeks in the encapsulated form and then checked for viability. The scale bar in (d), the fluorescence image, applies to both (c) and (d).

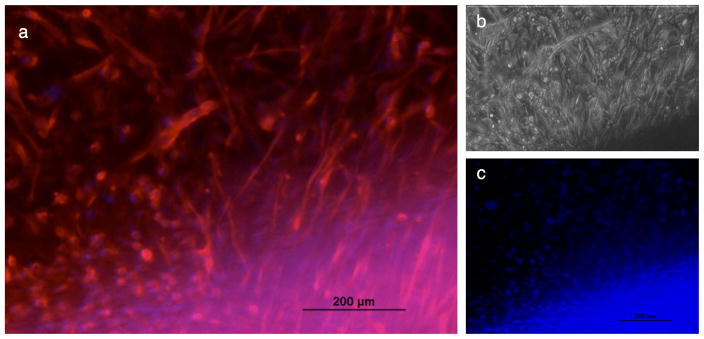

Extension of primary mouse statoacoustic ganglion or spiral ganglion neurites towards the Schwann cell-like cell-coated cochlear implant but not a bare cochlear implant was seen by time lapse digital microscopy

Cochlear implant electrodes of the ball type seen in Fig. 5b–d were then co-cultured with a) intact primary embryonic mouse statoacoustic ganglia or intact post-natal spiral ganglia or b) neurons dissociated from these ganglia to determine whether the neurites would demonstrate directional outgrowth towards the cell coated cochlear implants. We monitored the entire interaction by time-lapse digital videography on a specially designed microscope with a gas-supplied (5% CO2) tissue culture incubator on the stage over 5–14 days. Neurite migration and directional outgrowth trajectories were also photographed every 24 hrs after addition of the cochlear implants to cultures of the primary ganglia.

We first tested whether primary statoacoustic ganglion neurons exhibited directed neurite outgrowth toward cochlear implants coated with hydrogels that contained Schwann cell-like cells. A cocultured SAG explant and the Schwann cell coated cochlear implant or a SAG explant and a bare implant were placed 1 cm apart in the tissue culture dish and a video camera was programmed to capture images at different locations over the dish at 20 min intervals over 5–14 days. We then analyzed the images to observe any evidence of neurite extension or directional outgrowth from the ganglion towards the implant. No directed outgrowth was seen towards bare cochlear implants under any conditions. By contrast, after 2 days, 87%+ 4% of the processes took the direction towards the Schwann cell-like cell-coated cochlear implant, even if during the first 2 days some outgrowth was random and non-directional. We also observed that the explant itself in some cases split in half and some of the neurons themselves (with and without underlying glial cells) migrated in the cochlear implant’s direction.

The long-term co-culture (2 wks) of Schwann cell-like cell-coated cochlear implant and statoacoustic ganglia showed directional outgrowth of neurites and extensive contact of neuronal processes on the Schwann cell-like cell-coated cochlear implant from both statoacoustic ganglion neurons explants and dissociated cells. No neurite outgrowth whatever was seen towards “bare” cochlear implants, those coated with hydrogel but not cells or implants coated with hydrogels containing undifferentiated mESC. Although some processes were seen emerging from the ganglia under the three “control” conditions (bare implant, hydrogel but not cell coated implant or undifferentiated mESC in the hydrogels), the neurite processes were short, emerged randomly from all sides of the explants and showed no directionality or appreciable extension even after 2 weeks.

In marked contrast, from day 3 onwards, neuronal processes emerging from the statoacoustic ganglia were observed to turn in the direction of the Schwann cell-like cell-coated cochlear implants and to migrate towards them. The emerging neurites and some migrating cell bodies could be positively stained for neurofilament marker protein throughout the experiment.

By two weeks, the statoacoustic ganglion neurites had reached the cochlear implant (Fig. 7) and had penetrated the hydrogel layers containing Schwann cell-like cells in the hydrogel layers. Fig. 7 a and b are fluorescence micrograph (Fig. 7a) and phase contrast micrograph (Fig. 7b) of the same part of the coated electrode surface. In Fig. 7a Neurofilament 150kDa (Nfil) (red) was used to label the neuronal processes and a few cell bodies. In this double-labelled photograph, the blue staining (DAPI) is associated with the Schwann cell-like cell nuclei. These are more clearly visible in Fig. 7c, where the DAPI stained nuclei are heavily concentrated close to the electrode head and seen to belong to the Schwann cell like cells (compare Fig. 7c with 7a). A few neuronal cell bodies that stained with DAPI are seen in the area above the concentrated Schwann cell layers (Fig. 7c).

Figure 7.

Neurites of embryonic mouse (Eday 12.5) statoacoustic ganglion interact with Schwann cell-like cells in the hydrogel layers on a ball type cochlear implant at 2 weeks in culture. At the beginning of the experiment the statoacoustic ganglion was placed 1 cm away from the Schwann cell-like coated cochlear implant on a porcine gel coated tissue culture dish. Interactions with the cell coats on the impants were followed by time lapse digital cinematography over the entire 2 week period. The processes and some neuronal cell bodies reached the cochlear implant after 4–5 days. These photographs were taken at 13 days. (a) Neurites (and some cell bodies) were labelled by immunocytochemistry for Neurofilament 150kDa (Nfil) protein marker and a secondary antibody (AlexaFlor 580 (red) labels the extensive processes that had reached the cochlear implant. The blue crescent of labelling at the bottom represents the DAPI labelled Schwann cell-like cell nuclei. (b) the phase contrast micrograph view of these processes/cells from the statoacoustic ganglion and the implant (same field as (a). (c) DAPI-stained nuclei of the Schwann cell-like cells are seen in blue within the hydrogel “coats” in this micrograph of the “blue” channel. No directional statoacoustic ganglion neurite outgrowth was seen when the statoacoustic ganglion explants were co-cultured with a bare cochlear implant or with a cochlear implant coated with hydrogel layers containing undifferentiated stem cells.

Directional outgrowth of neurites from SGN was seen towards a variety of targets

Spiral ganglia isolated from the 6-day old postnatal mouse cochlea were also cocultured with bare cochlear implants, or with hydrogel coated cochlear implants containing Schwann cell-like cells or undifferentiated mESC. We used the same culturing techniques, cinematographic and photographic techniques to observe neurite extension and document any directional outgrowth both under the light microscope and by time-lapse live cell imaging. At the experiments end, the cultures were stained for neurofilament and DAPI. Again, we found that directional neurite outgrowth was only seen towards the Schwann cell-like cell coated-cochlear implants. Initially, as with the primary statoacoustic ganglia, at least some outgrowth of neurites was observed 360° around the cluster of spiral ganglion neuronal cell bodies. After the 3rd day of co-culture, the majority (91+6 %) of the neurites showed directional outgrowth towards the Schwann cell-like cell-coated cochlear implant and processes reached the implant by 8–9 days in culture. Neurite outgrowth from spiral ganglion neurons in the presence of a bare cochlear implant or one coated with undifferentiated mES cells showed little extension and no directional outgrowth at all even after 2 weeks in co-culture (data not shown).

These migration and directional outgrowth studies demonstrate that a Schwann cell-like cell-encapsulated cochlear implant could potentially deliver directional molecular cues to attract neurites of an endogenous adult spiral ganglion. Importantly, we had previously demonstrated that receptors for MIF remain on spiral ganglion neurons into adulthood (Bank et al., 2012).

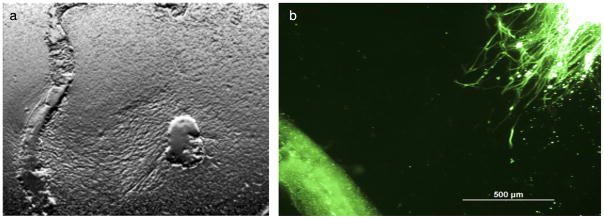

Neuron- like mESC-derived cells’ directional outgrowth towards targets

The MIF-induced/DHA enhanced neuron-like cells were assessed after a week of co-culture for directional migration and directional outgrowth towards: a) Organ of Corti explants derived from 6 day old postnatal mouse cochleae (wild type or derived from a MIF knock out mouse) as described in our previous studies (Bank et al., 2012); b) A bare cochlear implant; c) A cochlear implant coated with Schwann cell-like cells; d) A cochlear implant coated with undifferentiated mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC); e) A hydrogel coated cochlear implant without cells. The neuron-like cells exhibited few emerging processes and no directional neurite outgrowth toward the bare cochlear implant, the hydrogel-coated (no encapsulated cells) cochlear implant or the mESC-coated cochlear implant. In contrast neuron-like cells co-cultured with the Schwann cell-like cell-cochlear implant showed long processes, rapid migration and directional outgrowth towards the cochlear implant (71+11% of the processes were oriented towards the cochlear implant). However, these processes became so fasciculated that measurements of total “oriented” processes became difficult over time.

MIF-induced neuron-like cells co-cultured with the 6-day old postnatal wild type mouse Organ of Corti explants showed clusters of neurites with growth cones and multiple branches growing towards the wild type Organ of Corti (Fig. 8b). Compare this outgrowth with the robust neurite outgrowth emerging from a wild type primary spiral ganglion neurons towards the wild-type Organ of Corti explant seen in Fig. 8a. Little outgrowth, random emergence of processes and no directional outgrowth of neurites was seen if the Organ of Corti explant came from a MIF knock out mouse. These data recapitulate our finding with primary neurons and Organ of Corti explants. Neither statoacoustic ganglion neurites nor spiral ganglion neurites emerged towards a MIF knock out Organ of Corti explant (Bank et al., 2012). These studies indicate that the MIF/DHA-induced neuron-like cells derived after 3 weeks exposure to the neurotrophic cytokine MIF and DHA can migrate towards appropriate targets in vitro. Functionality is being tested electrophysiologically. However, directional outgrowth and electrophysiological function remain to be thoroughly tested when such electrodes are implanted in vivo in animal models.

Figure 8.

Interaction of primary spiral ganglion neurites (mouse post natal day 3 (a) and processes from MIF-induced neuron-like cell neurites (b) with wild type Organ of Corti explants in culture. (a) Polarized image of a primary mouse spiral ganglion (right) extending extensive neurites directionally toward a wild type Organ of Corti explant (at left). No directional outgrwoth was seen towards a MIF knock out mouse Organ of Corti (not shown). This was also demonstrated in separate experiments detailed in Bank et al., 2012, (Fig. 6 in that paper). (b) MIF-induced neuron-like cells stained with acetylated tubulin (green) cultured with a wild type Organ of Corti explant for a week showed fasciculated neurites (approaching form the right) growing towards the wild-type Organ of Corti (at lower left) No such outgrowth was seen towards OC explants from MIF-KO mice (as was also demonstrated for primary spiral ganglion neuronal processes in Bank et al., 2012 Fig. 6).

DISCUSSION

Concomitant differentiation of neuron-like cells and Schwann cell-like cells in a microfluidic device

Two novel stem cell-based therapeutic strategies for producing cell populations that could be used to alleviate sensorineural hearing loss have been assessed in these studies. We have differentiated a common population of mouse embryonic stem cells (mESC) (Doetschman et al., 1985; Roth et al., 2007, 2008, Bank et al., 2012) into neuron-like and Schwann cell-like cells simultaneously in a slow flow microfluidic device.

These studies were based on earlier work in which we used conventional tissue culture for such differentiation studies. Our lab had produced the first embryonic stem cell based model of both the myelinating and non-myelinating Schwann cell in 2007 (Roth et al., 2007, 2008). We also induced mouse embryonic stem cells to take on neuronal phenotypes with different characteristics depending on which neurotrophin was used as the inducing agent (NGF, CNTF: Roth et al., 2007, 2008; MIF: Bank et al., 2012). In these studies, we also used Neuregulin (as in Roth et al., 2007, 2008) to induce the mESC to become Schwann cell-like on the “Schwann cell” side of the microfluidic device.

Although both NGF and CNTF served as the “control” neuron-inducing agents in the microfluidic studies, we used MIF as the inducing neurotrophic cytokine in most of the studies detailed here both in the microfluidic model and in additional tissue culture based experiments. This was because we had previously demonstrated that MIF is the first neurotrophin expressed in the developing inner ear (Holmes et al, 2011; Shen et al., 2012; Bank et al., 2012), that it is responsible for the earliest steps in both neurogenesis and directional neurite outgrowth and that it is a neuronal survival factor (Bank et al., 2012). We had also previously demonstrated that inner ear spiral ganglion neurons retain the appropriate receptors for MIF into adulthood (Bank et al., 2012). The neuron-like cells induced by MIF in either conventional tissue culture dishes (Bank et al. 2012) or, as we show here in microfluidic devices, can bear significant resemblance to inner ear spiral ganglion neurons (Bank et al., 2012). The use of DHA enhances the maturation of such “neurons” in conventional tissue culture and in the microfluidic devices.

In the microfluidic devices, concomitant neuronal cell-type specific differentiation was seen and documented in morphological, molecular and electrophysiological assays in the devices themselves. These devices spare both cells and reagents and are labour-saving because the reservoirs supply a continuously delivered source of medium and factors (see the cartoons in Figs. 1c, d). Neuron-like cells extended processes over the Schwann cell lawns (Fig. 1a) and interactions between the ‘neurons’ and ‘Schwann cells’ resulted in the early steps of myelination (Fig. 4). We had previously demonstrated such directional outgrowth and early steps in myelination in conventional tissue culture experiments (Roth et al., 2008). The proximity of the two differentiating cell populations in the device is as critical for development of mature properties in both populations as it is in vivo. Without intimate contact with neurons, Schwann cells do not develop myelin components; nor, of course do they myelinate any cells in their environment except neurons. The role of MIF in myelination is under study in a number of systems. Disrupting pathways known to be downstream of MIF, such as Jab1, are known to cause dysmyenination (Porrello et al., 2011). Such pathways can be easily studied in these microfluidic devices and in model organisms such as the zebrafish (Weber et al., in preparation) as in more comprehensive studies of the events in myelination (Han et al., 2013; Glenn and Talbot, 2013).

The extremely slow flow maintained in the microfluidic device over 3 weeks allows for the accumulation of autocrine and paracrine factors that would ordinarily be washed through the device if the flow rate were accelerated (Park et al., 2009). This slow flow also allows for interactions between the two differentiating cell populations that emerge from the common population of ES cells—neuron-like and Schwann cell like cells. The two cell populations differentiate “side by side” and interactions between them can be documented.

We addressed the role of MIF in the observed directional outgrowth of neuron-like cells to the “Schwann cell” side of the device by inhibiting MIF’s down stream effects in one of two ways: use of the biochemical MIF inhibitor 4-iPP as we had done previously (Shen et al., 2012) or by using a function-blocking antibody to MIF, again as we had done in previous studies (Bank et al., 2012). We found that blocking MIF by either of these means on the Schwann cell side of the device once the embryonic stem cells had differentiated into Schwann cell-like cells, we could significantly reduce directional neurite outgrowth over the Schwann cell lawn, no matter which neurotrophin was used to induce the neuron-like phenotype (Fig. 2). However, the greatest effect was seen if MIF was the inducing agent or if MIF were enhanced with DHA. Note that blocking MIF did not totally eliminate directed neurite outgrowth over the Schwann cell lawn. This is because Schwann cells are known to produce another neurotrophic cytokine, monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP1) which also is produced by sensory hair cells of the inner ear (Bank et al., 2012) and which we have shown to affect both directional neurite outgrowth from inner ear neurons and their survival (Bianchi et al., 2005; Bank et al., 2012). The effect of blocking MCP1 was not tested in these experiments.

Meeting a long-term objective: Producing a stem-cell-derived neuronal population that phenotypically has some resemblance to that of the inner ear’s spiral ganglion neuron

One objective of these studies is to produce a stem cell-derived population of neuron-like cells that could potentially replace lost or damaged spiral ganglion neurons in human patients, potentially using a patient’s own induced pluripotent stem cells (Oshima et al., 2010) as a source of such neurons that could alleviate sensorineural hearing loss.

Researchers have previously attempted to develop glutamatergic neurons from ES cells by transient expression of neurogenin 1 and supplementation with BDNF and GDNF. These neurons were found to have some characteristics of spiral ganglion neurons, including electrophysiological functionality (Reyes et al., 2008). The ‘neurons’ were also implanted in an animal model (Reyes et al., 2008), although no functional improvement of a malfunctioning auditory system was demonstrated.

More promising later studies from the Rivolta group demonstrated that some significant improvement in hearing function could be achieved in a deafened gerbil model (Chen, Jongkamonwiwat et al., 2012) when human embryonic inner ear stem cells were implanted into the deafened animals. However, the derivation of neurons from human inner ear stem cells required a complex multi-step many week in vitro protocol for neuronal differentiation before implanting the cells. By contrast to these complex differentiation protocols, the ES to neuron conversion described here and in our previous studies requires only a single step with recombinant MIF (Bank et al. 2012). It is worth emphasizing that MIF is the inner ear’s earliest expressed neurotrophin and that this neurotrophic cytokine controls gangliogenesis in the vertebrate inner ear (Shen et al., 2012; Bank et al., 2012). Its use in eliciting a neuronal population is preferable to the use of other nerve growth factors (NGF, CNTF) or cytokines, largely because we have also demonstrated that ADULT SGN retain receptors for MIF (Bank et al., 2012).

Therapeutic Potential: A neuronal replacement strategy

Neuron-like cells derived from MIF and DHA-induced ES cells could potentially be used in the future to replace lost or damaged sensory neurons of the spiral ganglion in adults. However, if this paradigm is to be successful, several important hurdles will have to be met, some of which would be incurred in optimizing the neuronal cell implant procedure itself and some of which involve meeting critical criteria for monitoring functional connections of the “neuronal” population to the Organ of Corti if the implant were to be successful.

First, the cells must have cellular, molecular and electrophysiological properties sufficiently similar to the cells they replace to be functionally “competent” in situ. Second any implanted substitute “neuronal” population would have to remain viable and capable of extending “neurites” in vivo, towards a source of molecular cues that could provide directional signals and sustain their survival.

MIF is exactly such a neuronal directional outgrowth and survival factor (Holmes et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2012; Bank et al., 2012). MIF is produced in the native Organ of Corti by the supporting cells that underlie each sensory hair cell and by the Schwann cells of the inner ear (Bank et al., 2012). The neurite outgrowth documented in these microfluidic studies demonstrates that the neuron-like cells also respond to chemoattractant-producing (MIF-producing) Schwann cells in the microfluidic devices. Either a function-blocking antibody to MIF (Bank et al., 2012) or the biochemical MIF inhibitor, 4-iodo-6-phenylpyrimidine (4-IPP, Shen et al., 2012) can prevent directed outgrowth of these neuron-like cells towards the Schwann cell target cells, demonstrating that MIF production by the Schwann cell like cells is a key feature of the neuron-like cells’ directed outgrowth. A MIF-producing Schwann cell like cell-coated cochlear implant could also provide such cues and is discussed later in this section.

The number of surviving “neuron-like” cells has to be sufficient to provide functionally viable “neurons” over however many days are required for their neuronal processes to reach the target tissue (surviving hair cells in the Organ of Corti presumably via the MIF-producing supporting cells that cup each sensory hair cell) or the cochlear implant.

If the target tissue is the native Organ of Corti, the implant site would have to be optimized and two additional critical criteria would have to be met: the implanted cells cannot form a tumor or dedifferentiate and proliferate, even if the cell bolus that eventually forms is benign.

In the future, in order to prevent tumor formation in the inner ear, once the spiral ganglion neuronal processes have contacted the cochlear implant, a cell suicide cassette could be triggered to eliminate the Schwann cell-like cells (e.g. Li, Zhang et al., 2012), the cell debris of which would presumably be removed by macrophages. Slow release gels (e.g. Inaoka et al., 2009) that release recombinant MIF could also be used to coat the cochlear implants, but even with slow release, the supply of MIF in these gels would eventually be exhausted. It is not known how long it would be necessary to supply MIF to ensure that a maximum number of spiral ganglion neuronal processes reach the implant and form functional contacts. Using a stem cell-based source of MIF could provide the cytokine for a much longer time. The possibility of infection must also be minimized.

How far have we come towards realizing these criteria? MIF and DHA are capable of inducing some properties in the mESC-derived neurons that are similar to those of spiral ganglion neurons under the conditions of the experiment. These include: 1) VgluT1 (a marker for spiral ganglion neurons of the inner ear) transporter expression and protein, which was documented in MIF and DHA induced neuron-like cells.

However, the transporter is also expressed to the same extent in nerve growth factor- (NGF-) or ciliary neurotrophic factor- (CNTF-) induced mESC-derived neurons, each of which could also provide a viable source of ‘neurons’. 2) Electrophysiological excitability and the possibility of action potentials: Ion channel expression was assessed by RTqPCR and at the protein level by immunocytochemistry. The neuron-like cells’ physiological properties were evaluated by whole cell patch clamping. We were encouraged by the preliminary electrophysiological experiments showing that MIF+DHA could induce a neuronal population with promising electrophysiological properties. No inward or outward currents were found when electrophysiological recordings were made from the neuron-like cells induced by either NGF or NGF+DHA.

The cells also expressed ion channels (sodium and potassium channels) that are expected for spiral ganglion neurons (Greenwood et al., 2007; Xie et al., 2007), but sodium channel protein expression was better defined in the immunohistochemistry labeling experiments than potassium ion channel expression on the neurites.

These experiments demonstrate that these neuron-like cells express some functionally mature properties in common with spiral ganglion neurons under in vitro conditions. We have not yet documented action potentials under any of these conditions; such recordings will be attempted in the future.

Functionally mature neuron-like mESC-derived cells were experimentally tested for directional neurite outgrowth when cocultured with a cochlear implant or primary explanted Organ of Corti targets under in vitro conditions. They exhibited directional outgrowth towards both the Schwann cell-like coated cochlear implant and wild type but not the MIF knock out mouse Organ of Corti explants in culture. Therefore, neuron-like cells derived from mESC using MIF and DHA could potentially be implanted as a stem cell-based therapy in patients with low spiral ganglion counts who are not presently candidates for cochlear implant therapy.

Potential of ESC-derived Schwann cell-like cells for alleviating sensorineural hearing loss

The second embryonic stem cell based therapeutic approach described in these studies is the production of mESC-derived Schwann cell-like cells. These cells are potentially capable of continuous production of molecular cues, including MIF and MCP1, that could improve the number of connections between any remaining spiral ganglion neurons and a Schwann cell-like cell-coated cochlear implant.

In these studies, Schwann cell-like cell-coated cochlear implants in vitro were studied for their ability to “attract” neurites from both primary embryonic statoacoustic ganglion and the mature spiral ganglion. Eventually, such a strategy might be employed to enhance the functionality of a cochlear implant. If successful, this could lead to improved hearing or better speech perception in patients experiencing hearing loss.

Schwann cells are known to be important for peripheral nerve regeneration (Bhatheja and Field, 2006; Gambarotta et al., 2013). These properties depend on their state of differentiation (e.g. quiescent, proliferating or mature Schwann cells) (Baehr and Bunge, 1989; Kidd et al, 2013; Salzar, 2012, 2015; Grigoryan and Birchmeier, 2015).

In earlier studies by other investigators, the effects of factors secreted by Schwann cells were examined on a quasi-neuronal model composed of PC12 cells, which are, in some investigators’ estimations a model for neuronal cells, which were tested for cell survival and “neurite” outgrowth (Bampton and Taylor, 2005). In these experiments, Schwann cell-conditioned medium was tested on “neurite” outgrowth from PC12 cells against a range of isolated factors known to be secreted by Schwann cells. This conditioned medium showed clear neuritogenic effects and suggested that Schwann cells are likely candidates for promoting neuronal regeneration (Bampton and Taylor, 2005; see also Wissel et al., 2008).

Other groups have reported enhanced survival of spiral ganglion neurons in animal models of hearing loss by implanting Schwann cells, which were molecularly engineered to provide sustained delivery of neurotrophins such as BDNF (Bunge, 1993; Girard et al., 2005; Golden et al., 2007; Pettingill et al., 2008). Such an engineered population of Schwann cells was used to coat a cochlear implant, with some success in attracting spiral ganglion neurons to the implant (Pettingill et al., 2008).

However, the group attributed the attraction of the spiral ganglion neurons to the Schwann cells on the implant to the engineered neurotrophin expression and release by the Schwann cells. While this could indeed be the reason, it is also possible that since all Schwann cell express MIF, MIF was either the main source of or contributed to the attraction.

If this cell coated cochlear implant strategy were to be successful, initially after cochlear implant was introduced, electrical impedance should be higher due to the presence of the hydrogel encapsulated cells, but the biocompatible and biodegradable hydrogel might release the cells in the perilymph or area surrounding the cochlear implant, which could potentially provide sustained neurotrophin release, which would also serve to protect the spiral ganglion neurons. Once the hydrogel has completely degraded after releasing all the cells, the cochlear implant’s own electrical stimulation would presumably function normally, but this has not been examined either in vitro or in a living animal.

Combining stem cell based strategies

Various combinations of these approaches could be used. Neuron-like (especially potentially spiral ganglion-like) embryonic stem cell-derived cells could be implanted into an inner ear in which hair cell degeneration has begun but not yet progressed to complete loss. Potential stem cell sources could include a human patient’s own induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) (Oshima et al., 2010). Alternatively, stem cell-derived Schwann cell-like cells that are capable of sustained delivery of critical supporting factors like MIF could be used to coat a cochlear implant. Recall that all Schwann cells, including these engineered Schwann cell-like cells produce MIF (Huang et al., 2002, Bank et al., 2012). The research studies outlined here are limited to in vitro conditions; in the future this approach can be applied in animal models in in vivo studies.

Conclusions

These studies provide first steps towards producing MIF-induced stem cell derived neurons that could resemble spiral ganglion neurons sufficiently to replace lost or damaged spiral ganglion neurons. Furthermore, Neuregulin-induced Schwann cell-like cells that produce MIF could be used to “coat” a cochlear implant that provides a source of MIF to which both immature and mature auditory system neurons respond. We had earlier demonstrated that both neuronal subtypes retain MIF receptors (Bank et al., 2012). Thus a common population of “stem cells”, which in this report are mouse embryonic stem cells, but which in the future could be host derived iPS cells, can be induced to form two populations of cells that could provide viable approaches for auditory system repair.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Culturing mES cells

Cell lines: The cell line used for these studies was the D3 mES cell line (ATCC-CRL-1934; Doetschman et al., 1985). 10,000 mESC D3 cells were plated onto 0.1% porcine gel-coated (Sigma) 48 well Primaria® plates (Falcon) and cells were differentiated over a three-week period, using our previously-reported methods (Roth et al., 2007; 2008). Undifferentiated mES cells (controls) were fed basal medium daily, while cells in neuronal differentiation media and Schwann cell differentiation medium were fed every third day.

Media Preparation: Proliferating/undifferentiated (ES medium): 81% DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) without phenol red, but including 1% L-Glut, 1% Pen/Strep, 1% nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), 15% FBS (Atlanta Biological, Lawrenceville, GA, USA), 1% sodium pyruvate (2% stock, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 7 μL/L mercaptoethanol (Sigma Aldrich), 1,000 U/mL ESGRO (Chemicon, Temecula, CA, USA).

Differentiation of mES cell into Schwann cell-like cells in vitro

Our previously published methods were used to produce Schwann cell differentiation (Roth et al., 2007; 2008). The medium consisted of 500 mL alpha modified MEM (GIBCO 41061–029), 6% Day 11 chick embryo extract (prepared in house), 10% Heat Inactivated FBS, 58 μL Gentamycin (Invitrogen), 10 μL Neuregulin1 (NRG1) (R&D Systems).

Differentiation of mES cell into various neuron-like cell types in vitro