Abstract

The ventricular gradient, an electrocardiographic concept calculated by integrating the area under the QRS complex and T-wave, represents the degree and direction of myocardial electrical heterogeneity. Although the concept of the ventricular gradient was first introduced in the 1930s, it has not yet found a place in routine electrocardiography. In the modern era it is relatively simple to calculate the ventricular gradient in three-dimensions (the spatial ventricular gradient (SVG)), and there is now renewed interest in using the SVG as a tool for risk stratification of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. This manuscript will review the history of the ventricular gradient, describe its electrophysiological meaning and significance, and discuss its clinical utility.

History and definition of the ventricular gradient

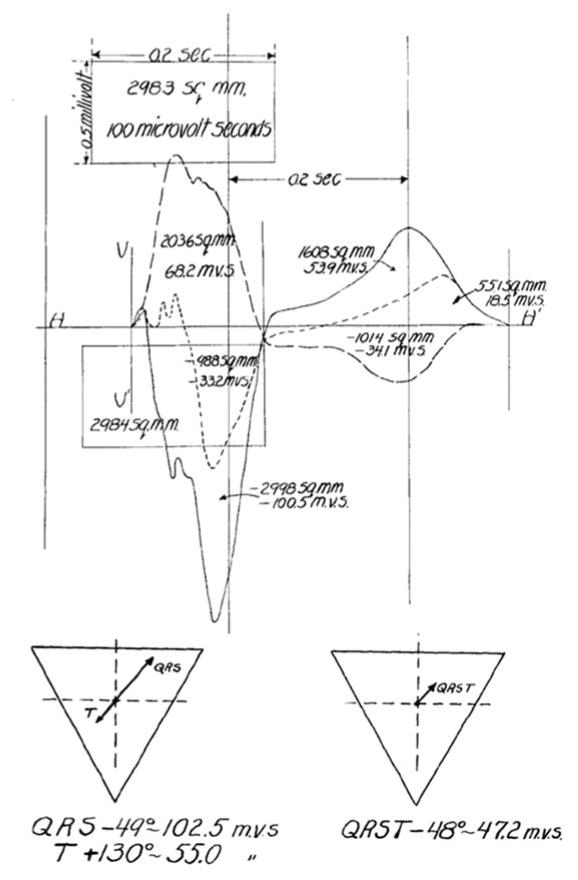

In the early 1930s, Frank Wilson and colleagues introduced the concept of the ventricular gradient [1,2]. Given that the area of any electrocardiographic deflection is equal to the deflection’s mean amplitude multiplied its duration, Wilson conceptualized the frontal plane mean electromotive forces (or mean electrical axes) of the heart during cardiac depolarization (QRS complex) and cardiac repolarization (T-wave) as vector quantities with components proportional to the sum of areas inscribed by the QRS complex and T-wave, respectively, in leads I, II, and III. He elegantly described how the algebraic sum of the area of the QRS complex and the area of the T-wave in a single lead would equal zero unless there was heterogeneity in either spatiotemporal depolarization/repolarization, duration of the excited state, or action potential morphology along the myocardial projection represented by the lead. Calculation of vectors representing the areas of the QRS complex and T-wave would therefore allow calculation of a third vector representing the entire QRST area (the ventricular gradient—the sum of the QRS area vector and T-wave area vector) which reflected the mean electrical axis of the heart and the net effect of local variations in the excitatory process throughout the frontal plane (Figure 1A) [1,2]. Wilson also suggested that the QRST area/ventricular gradient was independent of the speed of impulse propagation or the order of myocardial activation (such as during ventricular stimulation or bundle branch block) [1–4].

Figure 1.

A. Manual calculation of the ventricular gradient in the frontal plane by Wilson et al. [1] The area of the QRS complex and T-wave in leads I, II, and III, were used to create vectors representing the mean electrical QRS axis, the mean electrical T-wave axis, and the ventricular gradient (the mean QRST axis/the vector sum of the mean QRS axis and mean T-wave axis). See text for details. Reproduced with permission from Wilson et al. [1] B. An example of the spatial ventricular gradient (SVG). The SVG is a vector (red) which is the sum of the mean QRS area vector (dark blue) and mean T-wave area vector (dark green).

If there are no local variations in the duration of the excited state and myocardial depolarization and repolarization occur uniformly in the same spatiotemporal sequence, the QRS area and T-wave area vectors will have the same magnitude and exactly opposite orientation, resulting in a ventricular gradient with zero magnitude. In cases where local variations in the excited state are present and repolarization and depolarization are not spatiotemporally uniform throughout the heart, however, the ventricular gradient will point in the direction in which these variations are the greatest [1]. The ventricular gradient, therefore, is a vector that points from the area of myocardium with the longest mean duration of the excited state, to the area of myocardium with the shortest mean duration of the excited state [5].

The frontal plane ventricular gradient was extended into 3-dimensions (Figure 1B) (the spatial ventricular gradient (SVG)) in 1954 [5,6]. In 1957 Burger published a mathematical proof that demonstrated the SVG was theoretically independent of the initial site of stimulation, and that the SVG always points toward the area of myocardium with the shortest duration of the excited state [7]. The theoretical basis of the ventricular gradient was verified experimentally in 1959 by Gardberg and Rosen, who stimulated a strip of turtle ventricle suspended in an electrolyte bath and experimentally confirmed that the ventricular gradient of a muscle strip was independent of the site of ventricular stimulation [4]. Independence of the ventricular gradient from myocardial activation sequence was later reaffirmed in other experimental [8] and theoretical studies [9], including studies analyzing human body surface potential mapping [10]. Subsequent theoretical analyses demonstrated that SVG depends on heterogeneity of action potential area, shape, and duration [11].

However, the tenet of the independence of the ventricular gradient from the order of myocardial activation has been called into question by some experimental results [12–14]. In fact, the ventricular gradient may change depending on the site of cardiac stimulation because variations in the order of cardiac depolarization can induce local changes in the order of cardiac repolarization and action potential duration [15,16], and/or primary repolarization changes potentially due to cardiac memory [17,18]. Additionally, if the SVG is calculated from a transformed 12-lead ECG instead of from directly recorded X-, Y-, and Z-leads, variations in proximity of different leads to the heart and sites of stimulation might account for observed differences between theory and experiments [14]. These differences do not “disprove” the concept of the SVG, but rather suggest that other important/complex factors can influence it [14].

Measuring the SVG

Calculation of the SVG is more difficult than calculation of the ventricular gradient in the frontal plane as was done initially by Wilson, but digital electrocardiography and modern computer software make it simple to calculate SVG magnitude and orientation from the Frank (X-, Y-, Z-) ECG lead system, a matrix-transformed 12-lead ECG, or singular value decomposition [19]. In the vectorcardiographic approach to calculation of the SVG, the X-, Y-, and Z-components of the SVG are obtained by integrating the X-, Y-, and Z-ECG voltages over the entire QRST complex:

The SVG magnitude, azimuth, and elevation can then be computed using standard vector operations. It is important to note that due to variations in how three-dimensional vectorcardiograms are obtained/calculated, it may not be possible to directly compare values in different studies.

Theoretical examples illustrating the ventricular gradient

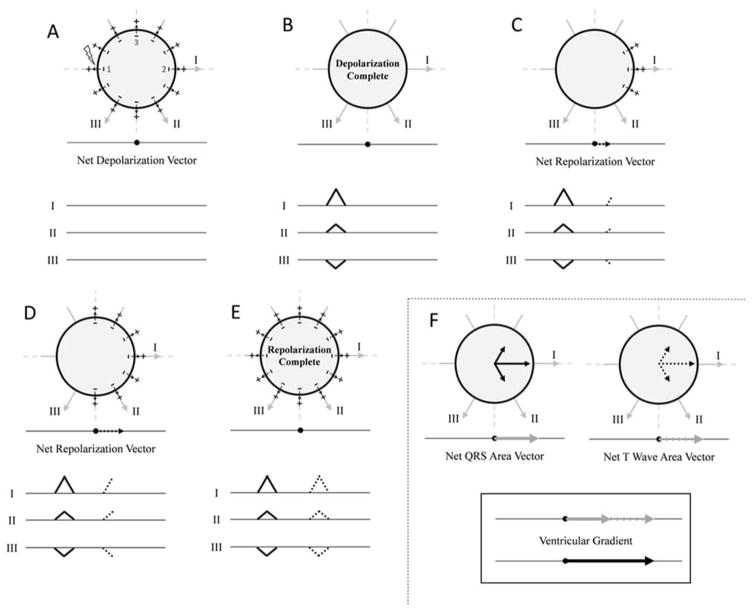

The concept of the ventricular gradient can be better understood by considering simple examples which are adapted here from Ashman and Byer’s and Hurst’s excellent reviews [3,20]. Consider a sphere of myocardium located in the center of the standard Einthoven triangle as shown in Figure 2. The left side of the sphere begins to depolarize at point 1 so that depolarization proceeds left to right. The vector representing depolarization is orientated towards lead I. As depolarization proceeds, the depolarization vector magnitude increases until the sphere is half-way depolarized. Magnitude then decreases back to baseline, inscribing a positive “QRS complex” in lead I. Lead II (with its axis located at +60°) will demonstrate a positive “QRS complex” that is half as tall as that in lead I, and lead III (with its axis located at +120°) will demonstrate a negative “QRS complex” with the same magnitude as lead II.

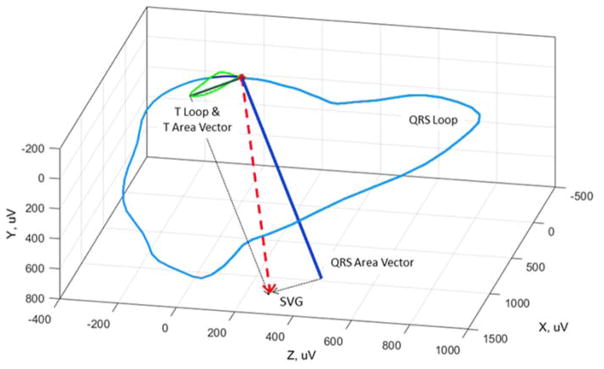

Figure 2.

Idealized example in which there is no ventricular gradient in a sphere of myocardium. If depolarization and repolarization occur in the same spatiotemporal order, there is no ventricular gradient. The orientation of leads I, II, and III are shown, as are the “electrocardiogram” tracings that would be observed in each lead. Panels A–E represent depolarization of an idealized sphere of myocardium. The myocardium is stimulated at point 1 and depolarization occurs from left to right inscribing “QRS complexes” in each lead. After a set amount of time, repolarization also begins at point 1 and also proceeds from left to right (panels F–H). The “QRS complex” and “T-wave” in each lead are therefore oriented in the opposite direction, with areas that are equal and opposite. Panel I summarizes the vector projections in each lead with vector magnitude proportional to the area of the QRS complex or T-wave in each lead. In this example, the “QRS” area and “T-wave” area vectors are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. The vector sum of the “QRS” area and “T-wave” area vectors (the ventricular gradient) is therefore zero. See text for details. Figure adapted from Hurst [20].

If there is spatiotemporal uniformity of action potential duration, after a fixed amount of time repolarization begins at the left of the sphere at the site that depolarized first (point 1). Repolarization then proceeds from left to right, but the vector of repolarization points from right to left, increasing in magnitude until the sphere is half repolarized, and then decreasing back to baseline. The “T-wave” will therefore be negative in leads I and II and positive in lead III, with areas equal and opposite to “QRS complex” area in each lead.

If vectors oriented along leads I, II, and III with magnitude equal to the area of the “QRS complex” in each lead are added (Figure 2, panel I), the net “QRS” area vector points directly towards lead I (towards 0°) and has magnitude M. Similarly, the net “T-wave” area vector points directly away from lead I (towards 180°), also with magnitude M. The sum of the net “QRS” area and “T-wave” area vectors is therefore zero and there is no ventricular gradient. It should be noted that although the “QRS complex” and “T-wave” have the same morphology in this theoretical example, their shapes can differ (although the area will be the same) due to differences in the relative speeds of depolarization and repolarization.

Next, consider that the sphere is depolarized starting at point 1 as previously described, but repolarization begins at the right side of the sphere (Figure 3). The net “QRS area” vector points directly towards lead I (0°) with magnitude M as previously described. Repolarization, however, now begins at point 2 on the right of the sphere, and the resulting vector of repolarization (also of magnitude M) points towards lead I (0°), exactly opposite to the vector of repolarization in the first example/Figure 1. The “T-waves” in all leads therefore point in the same direction as the “QRS complexes”, and the net “T-wave” area vector also points directly towards lead I (0°) with magnitude M. The ventricular gradient is therefore orientated towards lead I (0°) with a magnitude of 2M. The ventricular gradient points towards the area of myocardium that has the shortest duration of the excited state (point 2, which is depolarized last and repolarized first).

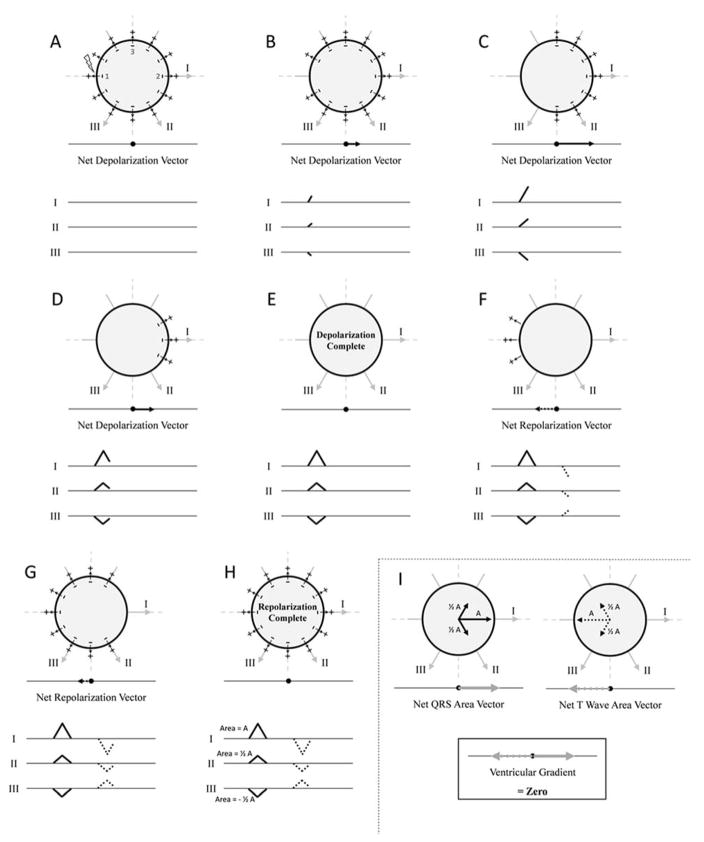

Figure 3.

Idealized example in which there is a ventricular gradient in a sphere of myocardium. If depolarization and repolarization begin in different parts of the sphere, a ventricular gradient is observed. Panels A–B represent depolarization of the myocardial sphere as shown in Figure 1 panels A–E. In this example, repolarization begins at point 2 and proceeds right to left (panels C–E). The “QRS complex” and “T-wave” in each lead are therefore oriented in the same direction. The net “QRS” area vector and net “T-wave” area vector therefore have the same area/magnitude (M) and point in the same direction (towards the right--0°). The ventricular gradient is oriented towards lead I (0°) with a magnitude of 2M. The ventricular gradient points towards the right of the sphere which is the area that has the shortest duration of the excited state (shortest duration between depolarization and repolarization). See text for details. Figure adapted from Hurst [20].

Finally, consider if repolarization begins at the top of the sphere at point 3 (Supplemental Figure 1). The net “QRS” area vector points towards lead I (0°), and the net “T-wave” area vector points upwards towards −90°. The ventricular gradient therefore points towards approximately −45° which is the area of the sphere that has the shortest duration of the excited state in this configuration.

The origin of the normal SVG

A SVG is present in all hearts, regardless of the presence or absence of pathology, due to normal non-uniformity in myocardial depolarization and repolarization. Normal epicardial/endocardial and apical/basal gradients of action potential duration [21] influence the normal SVG, although the reason for this normal heterogeneity is unclear. It has been suggested that variations in pressure gradients throughout the ventricle during the cardiac cycle might affect the timing of repolarization [20]. Ventricular sites with later local activation also tend to have shorter action potential duration, and “normal” action potential heterogeneity may therefore help prevent ventricular arrhythmias by “synchronizing” ventricular repolarization [17,22].

Normal limits of the SVG

Previous publications have proposed “normal” values for the ventricular gradient [23,24], but these values are outdated due to variations in ECG recording and measurement technology. In a recent study of 660 healthy participants in which SVG magnitude and orientation (azimuth and elevation) were calculated from 12-lead ECGs using an automated computer algorithm, significant gender differences were observed. Men had larger SVG magnitude than women: median 107 mV*ms (2nd–98th percentile 59–187 mV*ms) vs. median 79 mV*ms (2nd–98th percentile 39–143 mV*ms, respectively. Male SVGs were oriented more anteriorly than female SVGs: SVG azimuth median −24° (2nd–98th percentile −52 to 13°) vs. median −15° (2nd–98th percentile −38 to 20°), respectively. SVG elevation was similar in women and men: median 30° (2nd–98th percentile 12–48°) vs. median 28° (2nd–98th percentile 8–47°), respectively [25]. In another study of 160 healthy participants, similar gender differences in SVG magnitude were also observed: 103.6±31.8 mV*ms in men and 83.5±29.2 in women, respectively [26]. In general, the normal SVG is oriented along the long axis of the heart [27].

It should be noted, however, that there is significant variability in the magnitude and orientation of the SVG even among healthy people, and this variation is likely due to variations in orientation of the heart within the chest, heart rate, [25,28,29], postural changes [30], and autonomic influences independent of heart rate [31].

Use of the SVG as a way of differentiating “primary” and “secondary” T-wave changes

The SVG has historically been used to determine if T-wave changes are the result of primary repolarization abnormalities such as ischemia (primary T-wave changes), or if they are secondary to abnormal ventricular depolarization such as is observed with ventricular pacing or bundle branch block (secondary T-wave changes). The equation defining the ventricular gradient can be rewritten as:

where AT is the net T-wave area vector, AQRS is the net QRS area vector, and G is the ventricular gradient [27]. Changes in the QRS complex area or ventricular gradient will therefore cause changes in T-wave area/mean electrical axis of the T-wave. [27] The observed T-wave is a summation of primary and secondary changes [17].

In pure secondary T-wave changes (changes only due to abnormal ventricular depolarization) there is no change in SVG because overall heterogeneity of the duration of the excited state/action potential morphology/duration do not change (the potential caveats to this are noted above). Primary T-wave changes, such as those due to ischemia, will alter duration of the excited state/action potential morphology/duration, and these alterations will change the SVG. Primary T-wave changes are therefore reflected in SVG abnormalities [17,27,32].

Therefore, if there is an abnormal change in QRS morphology (such as with intermittent bundle branch block) and the SVG does not significantly change, observed changes in the T-wave are entirely due to abnormal ventricular depolarization. If the SVG does change, however, primary repolarization abnormalities are also present. Computer simulation examples of the effect of primary and secondary T-wave changes on the SVG are provided elsewhere [17]. The SVG therefore has potential utility in differentiating primary and secondary repolarization abnormalities in the setting of abnormal ventricular depolarization when it can be difficult to visually determine the etiology of T-wave changes. [32]

Other ECG parameters based on the SVG

The spatial QRS-T angle, the three-dimensional angle between the mean QRS vector and mean T vector, is another vectorcardiographic parameter based on the concept of the ventricular gradient. This ECG parameter is distinct and complementary to the SVG; it varies in response to secondary T-wave changes [33], and like SVG, it can also help differentiate primary and secondary T-wave changes [17]. Although it is not a direct measurement of the SVG, spatial QRS-T angle does depend on the three-dimensional orientation of the QRS and T vectors. Unlike the SVG, QRS-T angle (also reflected in a parameter known as the total cosine of the R-to-T), has been evaluated in numerous risk stratification studies. Increased QRS-T angle has been associated with total mortality and arrhythmic events in patients after myocardial infarction [34], total mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and sudden cardiac death in patients with end-stage renal disease on dialysis [35,36], more frequent appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapies [37], and sudden cardiac death in the general population [29,38,39].

Sum absolute QRST integral (SAI QRST) [26], a scalar analogue of the SVG, is another measure of global electrical heterogeneity defined as the algebraic sum of the X-, Y-, and Z-SVG components. SAI QRST has been associated with ventricular arrhythmias and appropriate implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapies in patients with prior myocardial infarction [40], and SCD in the general population [29].

The SVG as a marker of increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD)

Increased susceptibility to ventricular arrhythmias is associated with increased heterogeneity in myocardial activation and recovery times [41,42] and action potential duration [43]. The SVG reflects the degree of this heterogeneity, and is therefore a potential ECG marker of increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias and SCD. Despite the theoretical correlation between SVG and arrhythmic risk, however, few studies have evaluated the association between SVG and ventricular arrhythmias/SCD. In one small case-control study of 34 patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), the percent change in SVG magnitude during exercise was correlated with appropriate ICD therapies for ventricular arrhythmias [44].

We evaluated SVG magnitude, azimuth, and elevation in >20,000 participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study and Cardiovascular Health Study using digitally acquired 12-lead ECGs that were converted into vectorcardiograms. After adjusting for demographics, clinical characteristics, and other ECG parameters that have been associated with SCD, SVG magnitude was independently associated with SCD (HR 1.15 per 1 standard deviation increase, 95% CI 1.05–1.25, p=0.002). SVG azimuth and elevation lost their association with SCD after complete multivariable adjustment, potentially due to heterogeneity in participant characteristics and underlying cardiac disease [29]. Addition of SVG to clinical characteristics and other ECG parameters which also reflect myocardial global electrical heterogeneity (QRS-T angle and SAI QRST) was used to develop a risk score that significantly improved SCD risk prediction in the general population [29]. Further studies of the SVG as a measure of global electrical heterogeneity in various populations are needed.

Conclusion

The ventricular gradient, a vector defined as the sum of the net QRS area vector and net T-wave area vector, represents summation of local heterogeneity of the excited state throughout the entire heart. Although the ventricular gradient was first described >80 years ago, it has not yet been adopted into clincal practice, likely because until recently it was time consuming to calculate, and its clinical utility was unclear. With widespread use of digital electrocardiography and computerized ECG analysis programs, the SVG can now be easily calculated on almost any 12-lead ECG. Recent data have also demonstrated that measuring SVG magnitude and orientation can help identify people at increased risk of SCD. SVG, QRS-T angle, and SAI QRST are complementary ECG parameters that can be used to non-invasively assess myocardial global electrical heterogeneity. Based on recent studies [29], simultaneously assessing multiple parameters representing global electrical heterogeneity syngergistically improves SCD risk stratification. The SVG therefore has an important role in improving risk stratification of ventricular arrhythmias and SCD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Wilson FN, Macleod AG, Barker PS, Johnston FD. The determination and the significance of the areas of the ventricular deflections of the electrocardiogram. American Heart Journal. 1934;10:46–61. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson FN, Macleon FS, Barker PS. The T Deflection of the Electrocardiogram. Transactions of the Association of American Physicians. 1931;46:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashman R, Byer E. The normal human ventricular gradient: I. Factors which affect its direction and its relation to the mean QRS axis. American Heart Journal. 1943;25:16–35. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardberg M, Rosen IL. Monophasic curve analysis and the ventricular gradient in the electrogram of strips of turtle ventricle. Circ Res. 1959;7:870–5. doi: 10.1161/01.res.7.6.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burch GE, Abildskov AA, Cronvich JA. A study of the spatial vectorcardiogram of the ventricular gradient. Circulation. 1954;9:267–75. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.9.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonson E, Schmitt OH, Dahl J, Fry D, Bakken EE. The theoretical and experimental bases of the frontal plane ventricular gradient and its spatial counterpart. American Heart Journal. 1954;47:122–153. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(54)90221-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burger HC. A theoretical elucidation of the notion ventricular gradient. Am Heart J. 1957;53:240–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(57)90211-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lux RL, Urie PM, Burgess MJ, Abildskov JA. Variability of the body surface distributions of QRS, ST-T and QRST deflection areas with varied activation sequence in dogs. Cardiovasc Res. 1980;14:607–12. doi: 10.1093/cvr/14.10.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plonsey R. A contemporary view of the ventricular gradient of Wilson. J Electrocardiol. 1979;12:337–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(79)80001-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sridharan MR, Horan LG, Hand RC, et al. The determination of the human ventricular gradient from body surface potential map data. J Electrocardiol. 1981;14:399–406. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0736(81)81013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geselowitz DB. The ventricular gradient revisited: relation to the area under the action potential. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1983;30:76–7. doi: 10.1109/tbme.1983.325172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosma J, Levy B, Pipberger HV. The spatial ventricular gradient during alterations in the ventricular activation pathway. Am Heart J. 1966;71:84–91. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(66)90660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angle WD. The ventricular gradient vector and related vectors. American Heart Journal. 1960;59:749–761. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(60)90516-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abildskov JA, Burgess MJ, Millar K, Wyatt R. New data and concepts concerning the ventricular gradient. Chest. 1970;58:244–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.58.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abildskov JA. Effects of activation sequence on the local recovery of ventricular excitability in the dog. Circ Res. 1976;38:240–3. doi: 10.1161/01.res.38.4.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han J, Garcia de Jalon PD, Moe GK. Fibrillation threshold of premature ventricular responses. Circ Res. 1966;18:18–25. doi: 10.1161/01.res.18.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Draisma HH, Schalij MJ, van der Wall EE, Swenne CA. Elucidation of the spatial ventricular gradient and its link with dispersion of repolarization. Heart Rhythm. 2006;3:1092–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenbaum MB, Blanco HH, Elizari MV, Lazzari JO, Davidenko JM. Electrotonic modulation of the T wave and cardiac memory. Am J Cardiol. 1982;50:213–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(82)90169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acar B, Yi G, Hnatkova K, Malik M. Spatial, temporal and wavefront direction characteristics of 12-lead T-wave morphology. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1999;37:574–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02513351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hurst JW. Thoughts about the ventricular gradient and its current clinical use (Part I of II) Clin Cardiol. 2005;28:175–80. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960280404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel C, Burke JF, Patel H, et al. Is there a significant transmural gradient in repolarization time in the intact heart? Cellular basis of the T wave: a century of controversy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:80–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.791830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franz MR, Bargheer K, Rafflenbeul W, Haverich A, Lichtlen PR. Monophasic action potential mapping in human subjects with normal electrocardiograms: direct evidence for the genesis of the T wave. Circulation. 1987;75:379–86. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.2.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Draper HW, Peffer CJ, Stallmann FW, Littmann D, Pipberger HV. The Corrected Orthogonal Electrocardiogram and Vectorcardiogram In 510 Normal Men (Frank Lead System) Circulation. 1964;30:853–64. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.30.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pipberger HV, Goldman MJ, Littmann D, et al. Correlations of the orthogonal electrocardiogram and vectorcardiogram with consitutional variables in 518 normal men. Circulation. 1967;35:536–51. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.35.3.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scherptong RW, Henkens IR, Man SC, et al. Normal limits of the spatial QRS-T angle and ventricular gradient in 12-lead electrocardiograms of young adults: dependence on sex and heart rate. J Electrocardiol. 2008;41:648–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sur S, Han L, Tereshchenko LG. Comparison of sum absolute QRST integral, and temporal variability in depolarization and repolarization, measured by dynamic vectorcardiography approach, in healthy men and women. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bayley RH. On certain applications of modern electrocardiographic theory to the interpretation of electrocardiograms which indicate myocardial disease. American Heart Journal. 1943;26:769–831. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashman R, Byer E. The normal human ventricular gradient: II. Factors which affect its manifest area and its relationship to the manifest area of the QRS complex. American Heart Journal. 1943;25:36–57. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waks JW, Sitlani CM, Soliman EZ, et al. Global Electrical Heterogeneity Risk Score for Prediction of Sudden Cardiac Death in the General Population: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) and Cardiovascular Health (CHS) Studies. Circulation. 2016 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.021306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Batchvarov V, Kaski JC, Parchure N, et al. Comparison between ventricular gradient and a new descriptor of the wavefront direction of ventricular activation and recovery. Clin Cardiol. 2002;25:230–6. doi: 10.1002/clc.4950250507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vahedi F, Odenstedt J, Hartford M, Gilljam T, Bergfeldt L. Vectorcardiography analysis of the repolarization response to pharmacologically induced autonomic nervous system modulation in healthy subjects. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2012;113:368–76. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01190.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurst JW. Thoughts about the ventricular gradient and its current clinical use (part II of II) Clin Cardiol. 2005;28:219–24. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960280504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oehler A, Feldman T, Henrikson CA, Tereshchenko LG. QRS-T angle: a review. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2014;19:534–42. doi: 10.1111/anec.12206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zabel M, Acar B, Klingenheben T, et al. Analysis of 12-lead T-wave morphology for risk stratification after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;102:1252–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.11.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tereshchenko LG, Kim ED, Oehler A, et al. Electrophysiologic Substrate and Risk of Mortality in Incident Hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015080916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Bie MK, Koopman MG, Gaasbeek A, et al. Incremental prognostic value of an abnormal baseline spatial QRS-T angle in chronic dialysis patients. Europace. 2013;15:290–6. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borleffs CJ, Scherptong RW, Man SC, et al. Predicting ventricular arrhythmias in patients with ischemic heart disease: clinical application of the ECG-derived QRS-T angle. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2:548–54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.859108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chua KC, Teodorescu C, Reinier K, et al. Wide QRS-T angle on the 12-lead ECG as a Predictor of Sudden Death beyond the LV Ejection Fraction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jce.12989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porthan K, Viitasalo M, Toivonen L, et al. Predictive value of electrocardiographic T-wave morphology parameters and T-wave peak to T-wave end interval for sudden cardiac death in the general population. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:690–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tereshchenko LG, McNitt S, Han L, Berger RD, Zareba W. ECG marker of adverse electrical remodeling post-myocardial infarction predicts outcomes in MADIT II study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vassallo JA, Cassidy DM, Kindwall KE, Marchlinski FE, Josephson ME. Nonuniform recovery of excitability in the left ventricle. Circulation. 1988;78:1365–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.6.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kleber AG, Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:431–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Antzelevitch C. Heterogeneity and cardiac arrhythmias: an overview. Heart Rhythm. 2007;4:964–72. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Man S, De Winter PV, Maan AC, et al. Predictive power of T-wave alternans and of ventricular gradient hysteresis for the occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias in primary prevention cardioverter-defibrillator patients. J Electrocardiol. 2011;44:453–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.