Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the DNA methylation levels of steroidogenic enzyme genes in aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA), and the effects of gene mutations in APA on the DNA methylation levels. DNA methylation array analysis was conducted using non-functioning adrenocortical adenoma (NF, n=12), and APA (n=35) samples including some with a KCNJ5 mutation (n=21), an ATP1A1 mutation (n=5), and without known mutations (n=9). The quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay was performed for the detection of CYP11B2 and CYP11B1 expression levels in NF and APA. We introduced the KCNJ5 T158A mutation using lentivirus delivery in the human adrenocortical cell line (HAC15), and analyzed the effects of the mutation on DNA methylation levels. We analyzed the 83 presumed DNA methylation sites of steroidogenic enzymes. In APA, we found seven hypo-methylated sites in CYP11B2 and one hypo-methylated six hyper-methylated sites in CYP11B1. There were no differences in the steroidogenic enzymes gene DNA methylation of peripheral leucocytes between NF and APA. No CYP11B2 methylation level was associated with CYP11B2 transcription levels in APA. All methylation sites, except for a CYP11B2 region, showed no difference among APAs with or without gene mutations. HAC15 cells with the KCNJ5 mutation showed no changes in CYP11B2 or CYP11B1 methylation levels compared to control cells. We demonstrated that CYP11B2 in APA was extensively hypo-methylated, and CYP11B2 methylation in the region with hypo-methylation was not induced by KCNJ5 or ATP1A1 mutations that cause aldosterone over-production in APA and a KCNJ5 mutation HAC15 cells.

Keywords: aldosterone-producing adenoma, CYP11B2, CYP11B1, DNA methylation, KCNJ5 mutation

Introduction

Primary aldosteronism (PA) is the most common cause of secondary hypertension, and occurs by an excessive and autonomous production of aldosterone independent of the renin-angiotensin system.1 Patients with PA have an increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications compared with those with essential hypertension.2, 3 Therefore, the elucidation of the molecular mechanisms of aldosterone production is crucially important for the development of therapeutic agents for PA.

The two most common forms of PA are aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) and idiopathic hyperaldosteronism, also called as bilateral adrenal zona glomerulosa hyperplasia.1 Aldosterone is produced from the precursor cholesterol via a series of steroidogenic enzymes, and APA has higher levels of aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) which catalyzes the final steps of aldosterone biosynthesis.4, 5 Ca2+ signaling is up-regulated in APA,6 and it plays a pivotal role in the activation of CYP11B2 transcription.7 Recently, exome sequencing analyses demonstrated that 50-80% of APA harbored somatic mutations in KCNJ5, ATP1A1, ATP2B3, CACNA1D or CTNNB1. 8-12 KCNJ5, ATP1A1, ATP2B3, and CACNA1D mutation leads to increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration, activation of Ca2+ signaling, and an increase in CYP11B2 transcription.8-11 High CYP11B2 expression levels were found in APA with somatic CTNNB1 mutations which activated WNT signal.12, 13

Epigenetic regulation such as DNA methylation as well as intracellular signaling cascades is important for tumor progression, cell survival, DNA damage repair, and hormone secretion via their influence of gene transcription.14, 15 DNA methylation by DNA methyltransferase enzymes occurs at the cytosine of 5’-cytosine-guanine-3’ dinucleotides (CpG), where the methylation of the promoter region typically acts to repress the gene transcription.14 Previous reports demonstrated that methylation status might be regulated in APA,16-18 and a methylation site at the CYP11B2 promoter might be associated with CYP11B2 expression in adrenal tumors.17 However, there have been no reports regarding all presumed methylation sites of every adrenal steroidogenic enzymes in APA. The Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array enabled whole genome analysis and detection with more accurate results,19 and analysis using the method with a large sample size in APA has not yet been reported.

Taken together, we hypothesized that the steroidogenic enzymes in APA were regulated by not only intracellular Ca signaling but also by DNA methylation, and thus proposed to identify the methylation state of steroidogenic enzyme genes, including the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene, in APA by DNA methylation array analysis. To examine the association between gene mutation and DNA methylation, we further aimed to investigate the effect of gene mutations known to produce hyperaldosteronism in APA on methylation levels in APA and the human adrenocortical carcinoma cell line, HAC15.

Methods

Patients and tissue collection

Forty-seven adrenal tumors including 12 non-functioning adrenocortical adenomas (NF) and 35 APA were obtained by surgery, and stored at −80 °C until used. The pathological diagnosis of APA was confirmed by detecting the expression of CYP11B2 by immunohistochemistry and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assays as previously reported.5, 20 The clinical characteristics of the patients are showed in Table S1. The diagnosis and subtype diagnosis of primary aldosteronism was performed using the Japan Endocrine Society guideline,21 as previous described.20, 22 NF was diagnosed by radiological findings that consisted of lipid tissue by CT or MRI and endocrinological findings that did not show cortisol or aldosterone excess as previously reported.23 Our study was approved by the ethics committee of Hiroshima University, and written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

DNA extraction and genotyping

Genomic DNA from adrenal tissues, peripheral leucocyte DNA, and HAC15 cells were isolated by the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCR-based direct sequencing for KCNJ5, ATP1A1, ATP2B3, and CACNA1D were performed as previously described.20

DNA methylation analysis

More than 500ng of DNA, which underwent bisulfite conversion, was used for methylation analysis using the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction. The BeadChip interrogated more than 485,000 methylation sites per sample at single-nucleotide resolution, and it covered 99% of the RefSeq genes and 96% of the CpG islands.19 Methylation levels for each CpG residue were presented as β values which were employed to estimate the rate of the methylated signal intensity. The average β values were expressed as 0 to 1, representing completely non-methylated to completely methylated values, respectively.

RNA extraction and qPCR assays

Total RNA extraction and cDNA preparation were performed using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and the Takara PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan), respectively as previously described.20 The mRNA expression levels of CYP11B2, CYP11B1, and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) were determined using a Taqman® Gene Expression Assay kit (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). Gene expression levels were analyzed as arbitrary units normalized against GAPDH mRNA expression.

Cell culture and lentiviral infection

The HAC15 cell line was provided by WE Rainey (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and was cultured as previously reported.11 The plasmid pLX303 and pLX303-KCNJ5-T158A were prepared, and lentivirus production and infection in HAC15 cells were applied as previously reported.11

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are presented as the means and standard deviation. Heat maps were depicted by the R software package (University of Auckland), and subsequent analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (release 24.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The comparison of two groups between NF and APA were analyzed by Student's t-test or χ2 test. Simple regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the relationships of CYP11B2 or CYP11B1 mRNA expression levels with their methylation values. The relative expression of CYP11B2 and CYP11B1 were log transformed, because they did not fit a normal distribution. The statistical significances among genotypes were determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). In the case of statistically significant relations, the Bonferroni analysis was applied to assess the relationship between categories.

Results

DNA methylation profile of steroidogenic enzyme genes

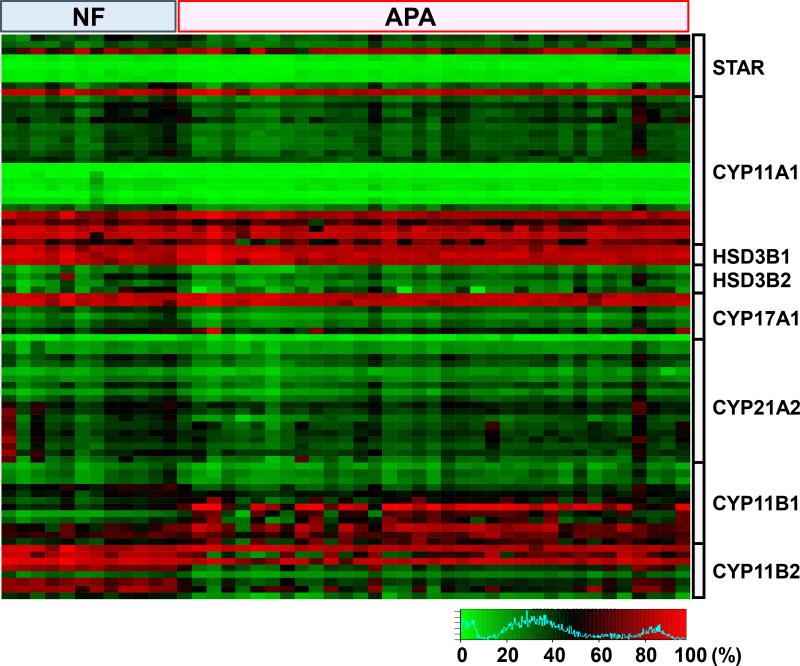

Eighty-three methylation sites (StAR: 9, CYP11A1: 22, HSD3B1: 3, HSD3B2: 4, CYP17A1: 7, CYP21A2: 18, CYP11B1: 12, CYP11B2: 8) were analyzed using the HumanMethylation450 BeadChip. The heat map of methylation profiles of steroidogenic enzymes was depicted in Figure 1. The statistical significances between NF and APA were obtained after Bonferroni adjustment, and CYP11B2 and CYP11B1 had significant differences in the methylation rate between the two groups. Next, to confirm the difference was not due to the germline, we compared the DNA methylation from peripheral leucocyte between NF (n=3) and APA (n=9). There were no significant differences of steroidogenic enzymes in peripheral leucocytes (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

A heat map was generated from the HumanMethylation450 BeadChip array analysis of non-functioning adenoma (NF, n=12) and aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA, n=35). Eighty-three methylation sites (StAR: 9, CYP11A1: 22, HSD3B1: 3, HSD3B2: 4, CYP17A1: 7, CYP21A2: 18, CYP11B1: 12, CYP11B2: 8) were analyzed.

CYP11B2 methylation profile in APA

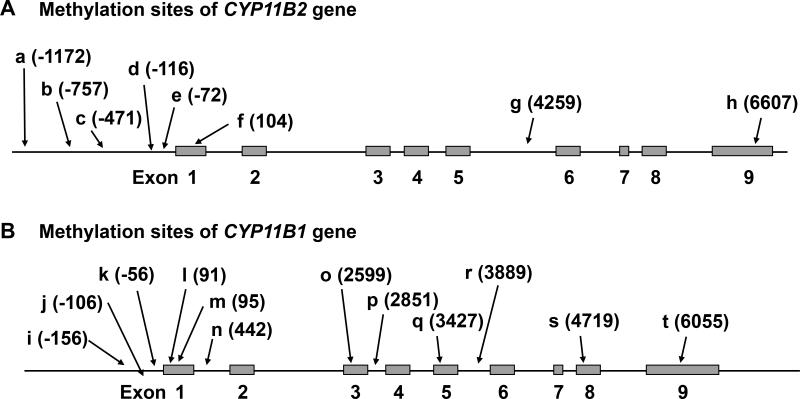

The conceivable methylation sites of CYP11B2 are shown in Figure 2A. Five sites are located in promoter region, and an exon, intron, and the 3’-untranslated region (3’-UTR) each has one methylation site. First, we compared the methylation rate of CYP11B2 between NF and APA, and all sites except for one promoter region were significantly hypo-methylated in APA (Table 1). Second, the associations of CYP11B2 mRNA expression levels with the CYP11B2 methylation values were analyzed by simple regression analysis. APA had 478.1-fold higher CYP11B2 mRNA expression levels compared to NF (P<0.01, Figure S2A), however there was no significant associations between CYP11B2 expressions and methylation in APA (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The presumed methylation sites of CYP11B2 (A) and CYP11B1 (B). The location from the transcription start site is indicated in parenthesis.

Table 1.

DNA methylation value of CYP11B2 and CYP11B1 in non-functioning adrenocortical adenoma and aldosterone-producing adenoma

| Methylation site | Methylation rate (β value) |

fold change (APA / NF) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NF average | APA average | |||

| CYP11B2 | ||||

| a | 0.839 ± 0.067 | 0.837 ± 0.048 | 1.00 | 0.927 |

| b | 0.818 ± 0.073 | 0.547 ± 0.187 | 0.67 | <0.001 |

| c | 0.901 ± 0.034 | 0.830 ± 0.068 | 0.92 | <0.001 |

| d | 0.744 ± 0.049 | 0.407 ± 0.121 | 0.55 | <0.001 |

| e | 0.303 ± 0.052 | 0.246 ± 0.050 | 0.81 | 0.004 |

| f | 0.710 ± 0.052 | 0.424 ± 0.089 | 0.60 | <0.001 |

| g | 0.745 ± 0.074 | 0.494 ± 0.154 | 0.66 | <0.001 |

| h | 0.419 ± 0.054 | 0.253 ± 0.083 | 0.61 | <0.001 |

| CYP11B1 | ||||

| i | 0.236 ± 0.071 | 0.207 ± 0.058 | 0.88 | 0.214 |

| j | 0.287 ± 0.081 | 0.275 ± 0.062 | 0.96 | 0.620 |

| k | 0.278 ± 0.077 | 0.251 ± 0.052 | 0.91 | 0.287 |

| l | 0.518 ± 0.055 | 0.375 ± 0.067 | 0.72 | <0.001 |

| m | 0.460 ± 0.068 | 0.466 ± 0.040 | 1.01 | 0.779 |

| n | 0.383 ± 0.064 | 0.483 ± 0.112 | 1.26 | 0.001 |

| o | 0.457 ± 0.061 | 0.811 ± 0.170 | 1.78 | <0.001 |

| p | 0.207 ± 0.047 | 0.517 ± 0.150 | 2.50 | <0.001 |

| q | 0.332 ± 0.065 | 0.487 ± 0.149 | 1.47 | <0.001 |

| r | 0.537 ± 0.098 | 0.720 ± 0.136 | 1.34 | <0.001 |

| s | 0.606 ± 0.041 | 0.642 ± 0.076 | 1.06 | 0.050 |

| t | 0.428 ± 0.052 | 0.541 ± 0.119 | 1.26 | <0.001 |

Data are expressed as means ± SD. P values were determined by t test. NF, non-functioning adrenocortical adenoma; APA, aldosterone-producing adenoma.

Table 2.

The relationship between CYP11B2 or CYP11B1 methylation levels and their mRNA expression levels in aldosterone-producing adenoma

| Methylation site | R | unstandardized β | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP11B2 | |||

| a | 0.105 | −0.86 | 0.548 |

| b | 0.061 | 0.13 | 0.727 |

| c | 0.208 | −1.19 | 0.230 |

| d | 0.071 | 0.23 | 0.685 |

| e | 0.104 | 0.81 | 0.533 |

| f | 0.055 | 0.24 | 0.754 |

| g | 0.067 | −0.17 | 0.701 |

| h | 0.250 | 1.17 | 0.147 |

| CYP11B1 | |||

| i | 0.071 | 0.39 | 0.684 |

| j | 0.012 | −0.06 | 0.945 |

| k | 0.003 | −0.02 | 0.987 |

| l | 0.271 | 1.29 | 0.115 |

| m | 0.090 | −0.72 | 0.608 |

| n | 0.320 | −0.92 | 0.061 |

| o | 0.192 | −0.36 | 0.269 |

| p | 0.280 | −0.60 | 0.104 |

| q | 0.394 | −0.85 | 0.019 |

| r | 0.095 | −0.23 | 0.586 |

| s | 0.015 | 0.06 | 0.932 |

| t | 0.348 | −0.95 | 0.040 |

The relationships were analyzed by simple regression analysis.

CYP11B1 methylation profile in APA

Figure 2B shows 12 presumed methylation regions in CYP11B1 including three in the promoter, five in exons, three in introns and one in the 3’-UTR. The methylation levels of six sites in APA were higher than those in NF, whereas one site was hypo-methylated in APA (Table 1). The CYP11B1 mRNA expression levels in APA had a 0.48-fold change compared to those in NF (P<0.01, Figure S2B). There were significant inverse correlations between methylation levels and CYP11B1 mRNA expression levels in two hyper-methylated sites of CYP11B1 (Table 2). However, these were not located in the promoter region.

Bioinformatics analysis of CYP11B2 promoter methylation sites

We detected multiple potential transcription factors that bind to the CYP11B2 promoter methylation sites using The JASPAR database (http://jaspar.binf.ku.dk/; Figure S3). We analyzed the gene expression levels of transcription factors with our microarray data published recently.20 Since some genes were highly expressed in APA (Figure S3), their effects on CYP11B2 transcription might be regulated by methylation status.

The relationship between the genotype of APA and DNA methylation levels

We compared DNA methylation values among APA with different gene mutations. A methylation site “a” of CYP11B2 in APA with the ATP1A1 mutation was significantly higher than those in APA with the KCNJ5 mutation (Table 3). However, the methylation site was different from the methylation sites which showed significant difference between NF and APA (Table 1), and did not have any correlation with CYP11B2 mRNA expression (Table 2). There were no significant differences in CYP11B1 methylation levels among APAs with different gene mutations (Table 3).

Table 3.

The difference of CYP11B2 and CYP11B1 DNA methylation levels among somatic mutations in aldosterone-producing adenoma

| Methylation rate (β value) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation site | KCNJ5 mutation (n = 21) | ATP1A1 mutation (n = 5) | no mutation (n = 9) | P value |

| CYP11B2 | ||||

| a | 0.820 ± 0.040 | 0.884 ± 0.027 | 0.852 ± 0.055 | 0.012 |

| b | 0.598 ± 0.159 | 0.470 ± 0.209 | 0.470 ± 0.216 | 0.138 |

| c | 0.846 ± 0.057 | 0.817 ± 0.092 | 0.799 ± 0.074 | 0.203 |

| d | 0.408 ± 0.095 | 0.350 ± 0.129 | 0.435 ± 0.169 | 0.461 |

| e | 0.256 ± 0.030 | 0.213 ± 0.058 | 0.242 ± 0.074 | 0.207 |

| f | 0.424 ± 0.073 | 0.388 ± 0.099 | 0.442 ± 0.120 | 0.566 |

| g | 0.498 ± 0.158 | 0.418 ± 0.153 | 0.528 ± 0.146 | 0.488 |

| h | 0.262 ± 0.063 | 0.230 ± 0.074 | 0.247 ± 0.128 | 0.735 |

| CYP11B1 | ||||

| i | 0.223 ± 0.049 | 0.161 ± 0.046 | 0.195 ± 0.071 | 0.076 |

| j | 0.289 ± 0.050 | 0.225 ± 0.052 | 0.269 ± 0.081 | 0.110 |

| k | 0.265 ± 0.041 | 0.217 ± 0.037 | 0.238 ± 0.071 | 0.111 |

| l | 0.373 ± 0.047 | 0.360 ± 0.080 | 0.387 ± 0.101 | 0.759 |

| m | 0.469 ± 0.035 | 0.484 ± 0.031 | 0.448 ± 0.053 | 0.244 |

| n | 0.488 ± 0.098 | 0.586 ± 0.193 | 0.414 ± 0.103 | 0.056 |

| o | 0.852 ± 0.138 | 0.834 ± 0.181 | 0.701 ± 0.200 | 0.075 |

| p | 0.544 ± 0.131 | 0.540 ± 0.158 | 0.442 ± 0.177 | 0.220 |

| q | 0.499 ± 0.133 | 0.561 ± 0.194 | 0.419 ± 0.148 | 0.196 |

| r | 0.742 ± 0.125 | 0.764 ± 0.087 | 0.644 ± 0.165 | 0.147 |

| s | 0.660 ± 0.067 | 0.631 ± 0.059 | 0.605 ± 0.094 | 0.184 |

| t | 0.555 ± 0.104 | 0.583 ± 0.137 | 0.486 ± 0.134 | 0.239 |

The methylation values among somatic mutations were analyzed. Data are expressed as means ± SD, and P values were determined by ANOVA.

Effect of KCNJ5 mutation on DNA methylation in HAC15

We introduced the KCNJ5 mutation (T158A) using the lentiviral method into HAC15 cells. Transduction of HAC15 cells with KCNJ5-T158A lentivirus mutation increased aldosterone levels 5.4-fold in media compared to control HAC15 cells (P<0.01, data not shown). There were no significant differences in CYP11B2 and CYP11B1 DNA methylation between control and mutant KCNJ5 cells (Table 4).

Table 4.

The difference of CYP11B2 and CYP11B1 DNA methylation levels between control and mutant KCNJ5 cells.

| Methylation site | Methylation rate (β value) |

fold change (KCNJ5 / control) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| control | KCNJ5 T158A | |||

| CYP11B2 | ||||

| a | 0.799 ± 0.044 | 0.804 ± 0.026 | 1.007 | 0.864 |

| b | 0.644 ± 0.018 | 0.632 ± 0.004 | 0.982 | 0.385 |

| c | 0.897 ± 0.002 | 0.913 ± 0.018 | 1.018 | 0.257 |

| d | 0.664 ± 0.008 | 0.688 ± 0.027 | 1.036 | 0.265 |

| e | 0.402 ± 0.025 | 0.403 ± 0.013 | 1.002 | 0.965 |

| f | 0.553 ± 0.017 | 0.577 ± 0.003 | 1.044 | 0.136 |

| g | 0.792 ± 0.027 | 0.789 ± 0.009 | 0.996 | 0.859 |

| h | 0.652 ± 0.012 | 0.661 ± 0.018 | 1.014 | 0.502 |

| CYP11B1 | ||||

| i | 0.660 ± 0.005 | 0.649 ± 0.036 | 0.983 | 0.641 |

| j | 0.388 ± 0.028 | 0.401 ± 0.024 | 1.032 | 0.594 |

| k | 0.490 ± 0.024 | 0.502 ± 0.013 | 1.026 | 0.486 |

| l | 0.787 ± 0.009 | 0.775 ± 0.004 | 0.985 | 0.130 |

| m | 0.738 ± 0.018 | 0.720 ± 0.003 | 0.975 | 0.223 |

| n | 0.880 ± 0.011 | 0.865 ± 0.014 | 0.983 | 0.228 |

| o | 0.962 ± 0.008 | 0.967 ± 0.001 | 1.005 | 0.391 |

| p | 0.674 ± 0.012 | 0.696 ± 0.011 | 1.033 | 0.081 |

| q | 0.686 ± 0.020 | 0.700 ± 0.018 | 1.020 | 0.416 |

| r | 0.858 ± 0.004 | 0.862 ± 0.022 | 1.004 | 0.805 |

| s | 0.926 ± 0.018 | 0.926 ± 0.004 | 1.000 | 0.977 |

| t | 0.847 ± 0.010 | 0.834 ± 0.018 | 0.984 | 0.341 |

DNA methylation rate was assessed in HAC15 infected with control (n=3) or KCNJ5 T158A lentiviruses (n=3). The methylation values between them were analyzed by Student's t-test.

Discussion

Detected in APA by DNA methylation array analysis, we demonstrated that seven of eight methylation sites of CYP11B2 were hypo-methylated and one and six sites of CYP11B1 were hypo-methylated and hyper-methylated, respectively. Four methylation sites were located in the promoter region of CYP11B2, although the methylation levels did not associate with the CYP11B2 transcription levels in APA. CYP11B1 had no regulated methylation region in its promoter, whereas some methylation rates in its exons or introns had an inverse relationship with CYP11B1 mRNA levels. All methylation sites, except for a CYP11B2 region, showed no difference among APAs with or without gene mutations, and an in vitro study also indicated that gene mutation did not influence the DNA methylation levels in CYP11B2 and CYP11B1.

We emphasize that most of the presumed CYP11B2 methylation sites were hypo-methylated in APA compared to NF. Considering basic studies of DNA methylation,14 the hypo-methylation in the promoter region could facilitate up-regulation of CYP11B2 expression in APA. Additionally, as our bioinformatics analysis showed, many potential transcription factors would be predicted to bind the sequence of the CYP11B2 promoter methylation sites. As we indicated that the methylation rate had no correlation with CYP11B2 expression levels in APA, it is suggested that total methylation status, not individual sites, might be important for CYP11B2 mRNA expression regulation.

We showed no relationship between CYP11B2 methylation levels and CYP11B2 expression in APA, and compared the results with previous studies. A previous study reported only one of the promoter methylation sites, which correspond to “d” in our study, and it had a significant relationship with CYP11B2 expression in all adrenal tissues combined with APA, NF, and normal adrenal gland.17 In applied same eligible tissues as the previous study, there was strong inverse correlation between the methylation rate and CYP11B2 expression (Figure S4). Therefore, our results that APA are hypo-methylated in “d” compared with NF are consistent with the previous report. Importantly, the relationship would be explained by the difference between APA and NF. Remarkably, in our study using a large sample of APAs, seven methylation sites of CYP11B2 were hypo-methylated, thus suggesting that full hypo-methylation of CYP11B2 could influence the CYP11B2 transcription in APA.

CYP11B1 in APA showed a lower mRNA expression and higher DNA methylation rate compared to NF (Table 1 and Figure S2), whereas there were no differences of serum cortisol levels by 1mg dexamethasone suppression test between APA and NF (Table S1). Previous studies revealed that there were no differences in CYP11B1 mRNA expression between APA and normal adrenal gland,24, 25 whereas in our study CYP11B1 expression seemed to be decreased in APA compared to NF (Figure S2). All of the CYP11B1 hyper-methylation sites with hyper-methylation existed outside the promoter region. It has been shown that exon or intron methylation can also regulate transcription by some possible mechanisms,26, 27 and thus CYP11B1 transcription in APA might be regulated by non-promoter DNA methylation. However, the CYP11B1 regulation machinery might not influence cortisol production in APA and NF, considering with the results of 1mg dexamethasone suppression test.

We also showed the effects of KCNJ5 and ATP1A1 mutations on DNA methylation of CYP11B2 and CYP11B1. CYP11B1 methylation was not observed to be influenced by the mutations in APA, whereas a methylation site in CYP11B2, indicated as “a” in our study, significantly differed among APAs with different mutations. The methylation site was not regulated between APA and NF, and there was no effect of a KCNJ5 mutation on the methylation status in vitro study. Therefore, it was thought that the site was not important for CYP11B2 transcription in APA. However, we need further ATP1A1 mutant APAs to detect reliable associations and basic study in HAC15 introducing a ATP1A1 mutation. More importantly, according to our in vitro study, CYP11B2 and CYP11B1 methylation or demethylation might not be regulated by a KCNJ5 mutation. It is suggested that the regulation machinery of CYP11B2 transcription and methylation could be different, and intracellular Ca2+ signaling stimulates CYP11B2 transcription, but not CYP11B2 DNA methylation. Taken together with our results and previous studies,14, 15 CYP11B2 mRNA expression in APA would be basically regulated by transcription factors, and hypo-methylation of CYP11B2 might facilitate or potentiate CYP11B2 transcription induced by transcription factors.

Limitations arise from the cross-sectional study design that do not allow the analysis of methylation and demethylation causality in APA and NF. A previous study applied in vitro performed methylation or demethylation analysis using a methyltransferase or demethyltransferase, respectively.17 However, these agents could regulate other mRNA expressions which regulate the CYP11B2 transcription by the altering their methylation status, and thus it did not address the direct analysis between methylation and mRNA expression. Further experiments will be needed to regulate DNA methylation or demethylation at targeted sites. The present study included a larger sample size than previous studies using the HumanMethylation450 BeadChip,17, 18 hence the results here study for the methylation state of steroidogenic enzyme genes in APA including somatic mutations are valuable.

Perspectives

APA exhibited hypo-methylated CYP11B2, and CYP11B2 methylation in the region with hypo-methylation was not induced by KCNJ5 or ATP1A1 mutations that cause aldosterone over-production in APA and a KCNJ5 mutation in HAC15 cells. CYP11B2 mRNA expression in APA would be basically regulated by transcription factors, and hypo-methylation of CYP11B2 might facilitate or potentiate CYP11B2 transcription induced by transcription factors. Therefore, our results regarding the CYP11B2 DNA methylation level in APA may be important for basic research helping to further clarify intracellular mechanisms of aldosterone production or to create therapeutic targets for aldosterone production regulation.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

1) What Is New?

This study is the first study showing that aldosterone-producing adenoma (APA) with a large sample size exhibited extensively hypo-methylated CYP11B2 using DNA methylation array analysis

CYP11B2 methylation level was not associated with CYP11B2 transcription levels in APA.

HAC15 cells with a KCNJ5 mutation showed no changes in CYP11B2 or CYP11B1 methylation levels compared to control cells.

2) What Is Relevant?

Hypo-methylated CYP11B2 might facilitate or potentiate CYP11B2 transcription induced by transcription factors in APA.

3) Summary

APA exhibited hypo-methylated CYP11B2, and DNA methylation of CYP11B2 was not induced by KCNJ5 or ATP1A1 mutations that cause aldosterone over-production in APA and a KCNJ5 mutation in HAC15 cells.

Acknowledgement

This work was carried out with the kind cooperation of the Analysis Center of Life Science, Hiroshima University.

Sources of Funding

This study was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP30638995 (KO), The Salt Science Research Foundation Grant Number 1424 (KO), Takeda Science Foundation (KO) and NIH grant HL27255 (CEGS).

Footnotes

Disclosure statements

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Funder JW, Carey RM, Mantero F, Murad MH, Reincke M, Shibata H, Stowasser M, Young WF., Jr. The management of primary aldosteronism: Case detection, diagnosis, and treatment: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:1889–1916. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milliez P, Girerd X, Plouin PF, Blacher J, Safar ME, Mourad JJ. Evidence for an increased rate of cardiovascular events in patients with primary aldosteronism. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005;45:1243–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reincke M, Fischer E, Gerum S, et al. Observational study mortality in treated primary aldosteronism: The german conn's registry. Hypertension. 2012;60:618–624. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bollag WB. Regulation of aldosterone synthesis and secretion. Compr Physiol. 2014;4:1017–1055. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c130037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomez-Sanchez CE, Qi X, Velarde-Miranda C, Plonczynski MW, Parker CR, Rainey W, Satoh F, Maekawa T, Nakamura Y, Sasano H, Gomez-Sanchez EP. Development of monoclonal antibodies against human cyp11b1 and cyp11b2. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;383:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sackmann S, Lichtenauer U, Shapiro I, Reincke M, Beuschlein F. Aldosterone producing adrenal adenomas are characterized by activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (camk) dependent pathways. Horm Metab Res. 2011;43:106–111. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1269899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pezzi V, Clark BJ, Ando S, Stocco DM, Rainey WE. Role of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase ii in the acute stimulation of aldosterone production. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;58:417–424. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(96)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi M, Scholl UI, Yue P, et al. K+ channel mutations in adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary hypertension. Science. 2011;331:768–772. doi: 10.1126/science.1198785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azizan EA, Poulsen H, Tuluc P, et al. Somatic mutations in atp1a1 and cacna1d underlie a common subtype of adrenal hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1055–1060. doi: 10.1038/ng.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beuschlein F, Boulkroun S, Osswald A, et al. Somatic mutations in atp1a1 and atp2b3 lead to aldosterone-producing adenomas and secondary hypertension. Nat Genet. 2013;45:440–444. 444e441–442. doi: 10.1038/ng.2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oki K, Plonczynski MW, Luis Lam M, Gomez-Sanchez EP, Gomez-Sanchez CE. Potassium channel mutant kcnj5 t158a expression in hac-15 cells increases aldosterone synthesis. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1774–1782. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akerstrom T, Maharjan R, Sven Willenberg H, et al. Activating mutations in ctnnb1 in aldosterone producing adenomas. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19546. doi: 10.1038/srep19546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Teo AE, Garg S, Shaikh LH, Zhou J, Karet Frankl FE, Gurnell M, Happerfield L, Marker A, Bienz M, Azizan EA, Brown MJ. Pregnancy, primary aldosteronism, and adrenal ctnnb1 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:1429–1436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klutstein M, Nejman D, Greenfield R, Cedar H. DNA methylation in cancer and aging. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3446–3450. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maqbool F, Mostafalou S, Bahadar H, Abdollahi M. Review of endocrine disorders associated with environmental toxicants and possible involved mechanisms. Life Sci. 2016;145:265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2015.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C, Zhou X, Jing J, Cheng J, Luo Y, Chen J, Xu X, Leng F, Li X, Lu Z. Decreased line-1 methylation levels in aldosterone-producing adenoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:4104–4111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Howard B, Wang Y, Xekouki P, Faucz FR, Jain M, Zhang L, Meltzer PG, Stratakis CA, Kebebew E. Integrated analysis of genome-wide methylation and gene expression shows epigenetic regulation of cyp11b2 in aldosteronomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E536–543. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murakami M, Yoshimoto T, Nakabayashi K, Tsuchiya K, Minami I, Bouchi R, Izumiyama H, Fujii Y, Abe K, Tayama C, Hashimoto K, Suganami T, Hata K, Kihara K, Ogawa Y. Integration of transcriptome and methylome analysis of aldosterone-producing adenomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173:185–195. doi: 10.1530/EJE-15-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dedeurwaerder S, Defrance M, Calonne E, Denis H, Sotiriou C, Fuks F. Evaluation of the infinium methylation 450k technology. Epigenomics. 2011;3:771–784. doi: 10.2217/epi.11.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kishimoto R, Oki K, Yoneda M, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Ohno H, Kobuke K, Itcho K, Kohno N. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulate aldosterone production in a subset of aldosterone-producing adenoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3659. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishikawa T, Omura M, Satoh F, Shibata H, Takahashi K, Tamura N, Tanabe A, Task Force Committee on Primary Aldosteronism TeJES Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of primary aldosteronism--the japan endocrine society 2009. Endocr J. 2011;58:711–721. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.ej11-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto T, Oki K, Kajikawa M, et al. Effect of aldosterone-producing adenoma on endothelial function and rho-associated kinase activity in patients with primary aldosteronism. Hypertension. 2015;65:841–848. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.05001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oki K, Yamane K, Nakanishi S, Shiwa T, Kohno N. Influence of adrenal subclinical hypercortisolism on hypertension in patients with adrenal incidentaloma. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2012;120:244–247. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1301896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bassett MH, Mayhew B, Rehman K, White PC, Mantero F, Arnaldi G, Stewart PM, Bujalska I, Rainey WE. Expression profiles for steroidogenic enzymes in adrenocortical disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:5446–5455. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fallo F, Pezzi V, Barzon L, Mulatero P, Veglio F, Sonino N, Mathis JM. Quantitative assessment of cyp11b1 and cyp11b2 expression in aldosterone-producing adenomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;147:795–802. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1470795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenet F, Moh M, Funk P, Feierstein E, Viale AJ, Socci ND, Scandura JM. DNA methylation of the first exon is tightly linked to transcriptional silencing. PLoS One. 2011;6:e14524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirectepe AK, Kasapcopur O, Arisoy N, Celikyapi Erdem G, Hatemi G, Ozdogan H, Tahir Turanli E. Analysis of mefv exon methylation and expression patterns in familial mediterranean fever. BMC Med Genet. 2011;12:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-12-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.