Abstract

Senescence is not only an important developmental process, but also a responsive regulation to abiotic and biotic stress for plants. Stay-green protein plays crucial roles in plant senescence and chlorophyll degradation. However, the underlying mechanisms were not well-studied, particularly in non-model plants. In this study, a novel stay-green gene, ZjSGR, was isolated from Zoysia japonica. Subcellular localization result demonstrated that ZjSGR was localized in the chloroplasts. Quantitative real-time PCR results together with promoter activity determination using transgenic Arabidopsis confirmed that ZjSGR could be induced by darkness, ABA and MeJA. Its expression levels could also be up-regulated by natural senescence, but suppressed by SA treatments. Overexpression of ZjSGR in Arabidopsis resulted in a rapid yellowing phenotype; complementary experiments proved that ZjSGR was a functional homolog of AtNYE1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Over expression of ZjSGR accelerated chlorophyll degradation and impaired photosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Transmission electron microscopy observation revealed that overexpression of ZjSGR decomposed the chloroplasts structure. RNA sequencing analysis showed that ZjSGR could play multiple roles in senescence and chlorophyll degradation by regulating hormone signal transduction and the expression of a large number of senescence and environmental stress related genes. Our study provides a better understanding of the roles of SGRs, and new insight into the senescence and chlorophyll degradation mechanisms in plants.

Keywords: Zoysia japonica, SGRs, senescence, chlorophyll degradation, RNA sequencing

Introduction

Senescence is not only an important developmental process, but also a responsive regulation to abiotic and biotic stress for plants (Wingler and Roitsch, 2008). Senescence of turfgrass and forage is of particular interest because the market value of these widely planted species are generally determined by the visual quality, nutritional value, and biomass accumulation. The most obvious phenomenon in senescence development is the change of leaf colors that usually turn from green to yellowish or red (Zhou et al., 2011). The underlying mechanism of senescence is far more comprehensive than the simple leaf color changes. It has been reported that senescence is highly programmed, including coordinated changes in cell structure, metabolism and genetic manipulation (Hörtensteiner, 2006; Schippers et al., 2015). By ultrastructual analysis, chloroplasts were proved to be the first organelles to be dismantled in senescence process (Dodge, 1970). Because the chloroplasts contain the majority of leaf protein that are attuned to be recycled during senescence in plants, the metabolic changes in chloroplasts may lead to drastic downstream regulation, suggesting the essential role of chloroplast disassembly in senescence (Jibran et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2015). Chlorophyll degrades via the multistep pheophorbide a oxygenase (PAO) pathway during senescence, comprising several chloroplast-located reactions (Christ and Hörtensteiner, 2014).

The STAY-GREEN (SGR) proteins function independently of PAO as key regulators in chlorophyll degradation (Hörtensteiner, 2006). Among the five identified SGRs mutants (A–E), the type C mutant with delayed chlorophyll degradation but normal decline rate of photosynthesis are the best characterized and utilized to further study the mechanism of chlorophyll degradation and senescence (Jibran et al., 2015). It has been identified from Lolium perenne (MacDuff et al., 2002), Oryza sativa (Park et al., 2007), Arabidopsis thaliana (Ren et al., 2007) and Medicago truncatula (Zhou et al., 2011). Sequence comparison results prove that SGRs are highly conserved proteins without any characterized domain, leading to the hypothesis that SGRs encode regulatory proteins regulating chlorophyll degradation rather than function as one particular enzyme (Hörtensteiner, 2006; Park et al., 2007). Functional studies suggest that SGRs are likely to function in dismantling of chlorophyll-apoprotein complexes and its expression could be a prerequisite for chlorophyll degradation in senescence (Hörtensteiner, 2006). Moreover, previous studies show that SGRs could play multiple roles in senescence besides chlorophyll degradation (Zhou et al., 2011; Christ and Hörtensteiner, 2014). Nevertheless, due to the limitation of traditional molecular biology approaches, the global picture of the regulatory networks of SGRs are not yet well-elucidated (Park et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2011). What's more, the study of chlorophyll degradation and senescence in the non-model plants lags far behind that in model plants.

To date, many emerging molecular techniques have been applied to explore the underlying mechanisms of plant senescence. Microarray analysis of Arabidopsis leaf developmental processes, M. truncatula stay-green mutants, and Populus tremula revealed that senescence in plant was a rather complex system (Andersson et al., 2004; Breeze and Buchanan-Wollaston, 2011; Zhou et al., 2011). RNA-seq was utilized in Gossypium hirsutum to better understand the leaf development and senescence, and it provided the first most comprehensive dataset for cotton leaf senescence (Lin et al., 2015). Chao et al. (unpublished) took advantage of the single-molecule real-time long-read isoform sequencing to explore the genetic regulatory network of leaf senescence in Medicago sativa. However, the global gene expression analysis focused on plant senescence is currently limited compared with that focused on biotic and abiotic stresses. Moreover, the underlying transcriptome dynamics are not well-elucidated due to the limited transcript profiling data of different species (Andersson et al., 2004; Breeze and Buchanan-Wollaston, 2011; Zhou et al., 2011). Therefore, it is vital to enrich the transcript profiles to better understand the senescence process at the transcriptional level and to further explore the functional roles of SGRs in senescence regulatory networks.

Zoysia japonica is a widely used warm-season C4 turfgrass species which owns many excellent characters, such as low maintenance requirements, good traffic tolerance and excellent tolerance to heat, drought, and salinity stresses (Patton and Reicher, 2007; Xu et al., 2015; Teng et al., 2016). However, the shorter green period of Z. japonica compared with cool season turfgrass is becoming a prominent barrier preventing its market promotion in the transition zone and the northern regions. It has been a desire of the turfgrass breeders for a long time to cultivate zoysiagrass cultivars with longer green period and better visual appearance. Nevertheless, limited genetic resources are available for zoysiagrass to date (Wei et al., 2015; Tanaka et al., 2016), and the senescence mechanism are far from being well-illustrated. The objectives of this study were: (i) to identify a stay-green protein gene in Z. japonica; (ii) to investigate its characters and explore its functional roles; and (iii) to further explore its regulatory network in senescence. Thus, ZjSGR was isolated and characterized from Z. japonica. The gene expression character, subcellular localization pattern, and functional roles were studied. Furthermore, the underlying regulatory mechanisms of ZjSGR were investigated using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) in ZjSGR-overexpressing Arabidopsis. This study will provide new insight into plant senescence induced by SGRs.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Z. japonica cultivar “Zenith” were planted in a greenhouse with temperature at 28/25°C (day/night) with a 14 h light period. A. thaliana ecotype Col-0 and nye1-1 (stay-green) mutant were used to generate transgenic lines. A. thaliana plants were cultivated in the nutrition medium containing peat, vermiculite and pearlite (1:1:1 in volume) and were kept at 24/22°C (day/night) with 16 h photoperiod and 65% humidity in growth chambers. Nicotiana benthamiana were cultivated in a growth chamber maintained at 24°C with a 16 h photoperiod. Half-strength Hoagland's solution was used weekly to fertilize the plants (Hoagland and Arnon, 1950).

Isolation of ZjSGR and its promoter

Total RNA and genomic DNA were isolated from “Zenith” leaves of 3-month-old using the Trizol method (Invitrogen, USA), and the CTAB method, respectively. Using PrimeScript RT Master Mix (TaKaRa, Japan), the cDNA was obtained with total RNA as template. Using the ZjSGR-F and ZjSGR-R (Table 1), the cDNA sequence and gDNA sequences of ZjSGR were amplified. To obtain the promoter sequence of ZjSGR, TAIL PCR was carried out using a Genome Walking Kit (TaKaRa, Japan) with genomic DNA as template. Three gene specific primers, SGR-R1, SGR-R2, and SGR-R3 (Table 1), were used in the chromosome walking. Based on the sequencing data, the promoter-specific primers, Promoter-F, and Promoter-R, were synthesized to amplify the upstream sequence of ZjSGR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Primers used for gene cloning, qRT-PCR detection and plasmid construction.

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| ZjSGR-F | CCAGGAGAAGGGAAGGCGCGAACAT |

| ZjSGR-R | TTGTCATCACCGGTCCCCGTGTCAC |

| SGR-R1 | CTTCCGGAAGATGTAGTACCGGAGG |

| SGR-R2 | GCAGCGACATCCGGCCGCGCACCTT |

| SGR-R3 | CGGTTGTACCACCCCTGCAGCTGCGCG |

| Promoter-F | CAACCACTGTGACTTGGAAGTTATG |

| Promoter-R | CTGCTTGAGCTGGGAGATCTG |

| ZjACT-F | GGTCCTCTTCCAGCCATCCTTC |

| ZjACT-R | GTGCAAGGGCAGTGATCTCCTTG |

| qSGR-F | CGTCCACTGCCACATCTCCG |

| qSGR-R | CGAACGCCTTCAGCACCACA |

| 3302Y-SGR-F | cacgggggactcttgaccatggtaATGGCTGCGGCCATTTCGG |

| 3302Y-SGR-R | ggtacacgcgtactagtcagatcCTGCTGCGTCTGGCCAGCG |

| 3302FLAG-SGR-F | gagaacacgggggactcttgacATGGCTGCGGCCATTTCGG |

| 3302FLAG-SGR-R | ccttgtaatccagatctaccatCTGCTGCGTCTGGCCAGCG |

| 3302GUS-SGR-F | aagcctagggaggagtccacCAACCACTGTGACTTGGAAG |

| 3302GUS-SGR-R | tttaccctcagatctaccatGTTCGCGCCTTCCCTTCTC |

| Complement-F | aagcctagggaggagtccacCAACCACTGTGACTTGGAA |

| Complement-R | tttaccctcagatctaccatTTGTCATCACCGGTCCCCGT |

| AtrbcL-F | GGGTTCAAAGCTGGTGTTAAAG |

| AtrbcL-R | CTCGGAATGCTGCCAAGATA |

| AtPSAF-F | ACGGGAAGTACGGATTGTTATG |

| AtPSAF-R | CGATCCATCCAGCAATGTAGAG |

| AtCAB1-F | AGGAACCGTGAACTAGAAGTTATC |

| AtCAB1-R | CCGAACTTGACTCCGTTTCT |

| AtRCA-F | GTCCAACTTGCCGAGACCTAC |

| AtRCA-R | TTTACTTGCTGGGCTCCTTTT |

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of leaves at different senescent stages and other tissues (roots and stems) were used to explore the expression pattern of ZjSGR in zoysiagrass. ZjSGR expression profiles were examined in 3-month-old zoysiagrass after 24 h induction with darkness, 10 μM ABA, 10 μM MeJA, or 0.5 mM SA. Reactions were performed in a 96-well blocks qRT-PCR system (CFX Connect, BIO-RAD, USA) using SYBR Premix (TaKaRa, Japan) in total volumes of 25 μL. The two-step qRT-PCR profile was set as follows: initial denaturing step of 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 0.05 s, and 60°C for 30 s. The Z. japonica beta-actin was selected as the internal reference gene (GenBank accession No. GU290546) (Table 1). Gene specific primers, qSGR-F and qSGR-R (Table 1), used for qRT-PCR were designed based on the cDNA sequence. For the relative gene expression analysis in transgenic Arabidopsis, the AtUBQ10 was selected as the internal reference, and all the related gene specific primers used in this study could be found in Table 1. The primers used for the RNA-seq data verification were listed in Table S1. The relative expression level was figured out using the comparative ΔΔ Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). All data are presented as the means (with corresponding standard deviations, SD) of four independent RNA templates, each of which included four technical replicates.

Construction of vectors and generation of transgenic Arabidopsis

The 35S::ZjSGR:YFP fusion construct was created by inserting the complete ORF of ZjSGR into plasmid 3302Y (Jia et al., 2016). Primers 3302Y-SGR-F and 3302Y-SGR-R (Table 1) were used to amplify the ZjSGR coding sequence (Table 1), which was then purified and inserted into 3302Y vector digested with BglII (TaKaRa, Japan) using an In-fusion HD Cloning Kit (TaKaRa, Japan). The 35S::ZjSGR:FLAG fusion construct was created by inserting the complete ORF of ZjSGR into plasmid 3302FLAG. Primers 3302FLAG-SGR-F and 3302FLAG-SGR-R (Table 1) were used to amplify the ZjSGR coding sequence (Table 1), which was then purified and inserted into 3302FLAG vector digested with NcoI (TaKaRa, Japan) using an In-fusion HD Cloning Kit (TaKaRa, Japan).

The ZjSGRpro::GUS fusion construct contained an 1029 bp ZjSGR 5′ upstream sequence. The promoter region was amplified from plasmid containing the target sequence using primers 3302GUS-SGR-F and 3302GUS-SGR-R (Table 1). The 3302GUS vector (without 35S promoter) was digested with NcoI (TaKaRa, Japan), and then the purified ZjSGR promoter was inserted into the digested vector using an In-fusion HD Cloning Kit (TaKaRa, Japan) to produce the ZjSGRpro::GUS fusion construct. To obtain the ZjSGRpro::ZjSGR:GUS construct, the target fragment was amplified using Complement-F and Complement-R, and then it was subcloned into the 3303GUS vector.

Using the floral dip method, Agrobacterium GV3101 containing the constructed plasmids were used to transform Arabidopsis plants to generate transgenic plants expressing 35S::ZjSGR:YFP (for subcellular localization observation), 35S::ZjSGR:FLAG (for overexpression assay), or ZjSGRpro::GUS (for promoter activity analysis) and ZjSGRpro::ZjSGR:GUS (for complementation test), respectively. Transformed Arabidopsis seeds were screened using 60 mg·L−1 glufosinate. Positive transgenic plants were verified by RT-PCR and genomic PCR. Representative T3 generation transgenic lines that exhibited 100% resistance to glufosinate were harvested for further phenotype observation and measurements.

Phenotype observation and sampling time

The seedlings were cultivated in growth chambers for 4 weeks and then the phenotype was photographed using a digital camera (EOS 60D, Cannon, Japan) and the chlorophyll content, gene expression, and photosynthesis were determined. For the complementation test, the detached rosette leaves of independent complementary T3 lines were incubated in 3 mM MES buffer (pH 5.7) for 4 days in total darkness condition and then were photographed and sampled for gene expression level assay. For the promoter activity determination, T3 seedlings were cultivated in MS medium in the growth chamber for 2 weeks and then were kept in darkness or transplanted to the MS medium containing 10 μM ABA and 10 μM MeJA for 3 days, respectively. After that, the GUS assay was carried out according to the protocol of (Cervera, 2005).

Subcellular localization of ZjSGR and GUS assay of ZjSGRpro::GUS transgenic seedlings

Using the stable transformed ZjSGR-overexpressing Arabidopsis, the subcellular localization character of ZjSGR was investigated using a laser confocal scanning microscope (SP-5, Leica, Germany). Using the stable transformed ZjSGRpro::GUS transgenic Arabidopsis lines, the GUS staining was carried out. After 3-day inducement under darkness and hormones, the seedlings were then photographed using a stereomicroscope (M205 FA, Leica, Germany).

Determination of chlorophyll contents and photosynthesis

The chlorophyll content was measured according to the protocol of Knudson et al. (1977). In brief, leaf tissue (0.05 g) was immersed in 8 mL 95% ethanol in dark for 48 h, and the extraction was determined. The contents of chlorophyll a (Chl a) and chlorophyll b (Chl b) were measured with a spectrophotometer (UV-2802S, UNICO, Spain) by recording the absorbance at 649 and 665 nm. The chlorophyll content was calculated using the formulas: Chl (mg g−1 FW) = (6.63A665 + 18.08A649) × V/W, [A, optical density at 665 and 649 nm; V, final volume (milliliters); FW, leaf tissue fresh weight (grams)]. The net photosynthetic rate (Photo), stomatal conductance (Cond), intercellular-space CO2 concentration (Ci), and transpiration rate (Tr) were determined using photosynthesis system (Li6400XT, Li-Cor, USA) with a constant airflow rate of 500 μmol s−1 and ~400 μmol mol−1 CO2 concentration at 28°C.

Chloroplast structure observation by transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) observation was carried out according to the method of Park et al. (2007) with minor modifications. Briefly, leaf tissues segments were fixed with a fixative buffer containing 2% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde, and 50 mM sodium cacodylate (pH 7.2). Then the fixed tissues were washed three times with 50 mM sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) at 4°C. The samples were incubated in 50 mM sodium cacodylate buffer containing 1% osmium tetroxide (pH 7.2) at 4°C for 2 h. Then the samples were washed twice with distilled water at 25°C, and immersed in 0.5% uranyl acetate for at least 30 min at 4°C, and then dehydrated in a gradient series of propylene oxide and ethanol before finally embedded in resin. Ultrathin sections were generated with an ultra-microtome and placed on copper grids after being polymerized at 70°C for 24 h. The samples on the grids were treated with 2% uranyl acetate for 5 min and with Reynolds′ lead citrate for 2 min at 25°C, and then photographed using a transmission electron microscope (HT7700, Hitachi, Japan).

RNA-Seq analysis

Total RNA was extract from 3-week-old Arabidopsis using Trizol methods (Invitrogen, USA). RNA purity, concentration and integrity were determined with NanoPhotometer (IMPLEN, Germany), Qubit 2.0 Flurometer (Life Technologies, USA) and Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, USA), respectively. Three micrograms of RNA per sample was used to prepare RNA samples. Sequencing libraries were generated (3 μg RNA per sample) according to the manufacture's recommendations of NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA). Index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. The clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using TruSeq PE Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumia, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Then the libraries were sequenced on an Illumia HiSeq™ 4000 platform by Novogene Technologies (Beijing, China). Clean reads from the each library were mapped to reference Arabidopsis genome using TopHat v2.0.12 (Kim et al., 2013). The reads numbers mapped to each gene were counted using HTSeq v0.6.1 (Anders, 2015). FPKM was used to determine the gene expression levels. Genes with an adjusted P < 0.05 and absolute value of log2 FC ≥ 1 were assigned as differential expressed genes (DEGs) in the six libraries from ZjSGR transgenic plants (line SGR-7) and WT (3 libraries per group). For gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis, all the DEGs were mapped to GO terms in the GO database (http://geneontology.org/). KOBAS software (Mao et al., 2005) was utilized to test the statistical enrichment of the DEGs in KEGG (http://www.kegg.jp/) pathways. The reliability of the RNA-seq data was confirmed by Pearson's correlation plot. The raw sequence reads were deposited into the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Short Read Archive (SRA) repository under the accession number SRP093808.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were prepared from plant tissues using Trizol methods (Invitrogen, USA), and measured using the Bradford protein assay (BioRad, USA). Total protein (5 μg) samples were separated on a 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a pure nitrocellulose blotting membrane (PALL, USA), and consecutively probed with a Mouse mAb antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, USA) and an Anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, USA). The DAB Kit (SIGMA, Germany) was used to detect the immune complex.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed statistically with Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft, USA) and SPSS version 19 statistical software (SPSS Inc., USA).

Results

Isolation and characterization of the SGR gene and its promoter

The ZjSGR cDNA and gDNA sequences were deposited in the NCBI database with accession numbers KP148819 and KP148820, respectively. The ZjSGR protein consisted of 276 amino acids and belonged to the stay-green superfamily. A 1029 bp fragment of the ATG initial codon was obtained for promoter elements deduction and promoter activity assay. Multiple light responsive elements were identified, including AT1-motif, Box 1, Box 4, CATT-motif, MNF1, SP1, and TCT-motif (Table S2). Of particular interest, several elements involved in responses to phytohormone inducements were also detected, including CGTCA-motif (MeJA-responsiveness), TGACG-motif (MeJA-responsiveness), TCA-element (salicylic acid responsiveness), and TGA-element (auxin-responsive element; Table S2). These cis-regulatory elements encouraged us to explore the expression character of ZjSGR under phytohormone inducements.

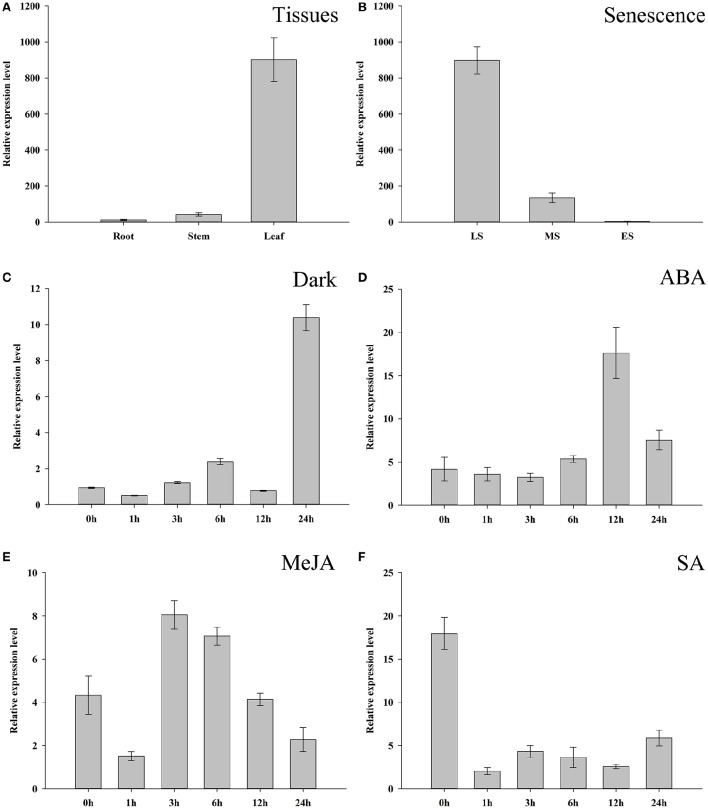

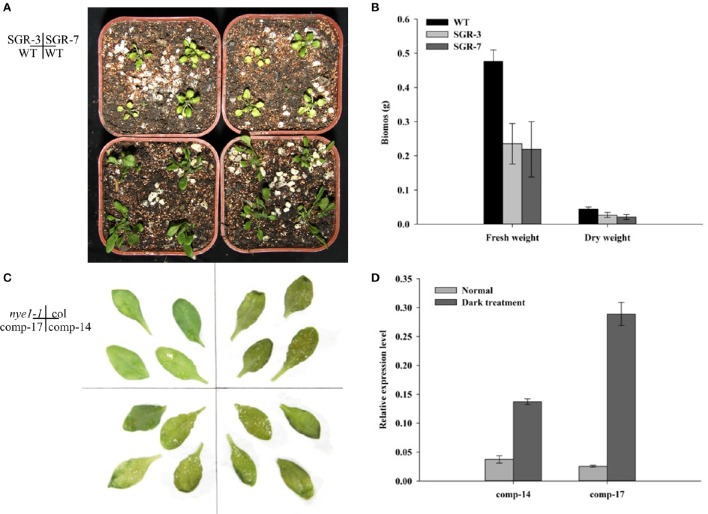

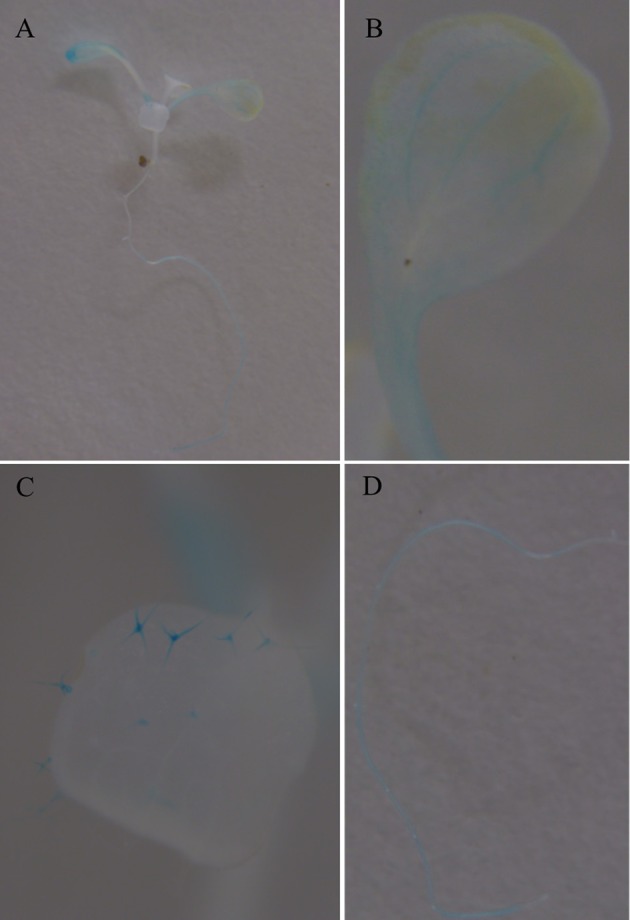

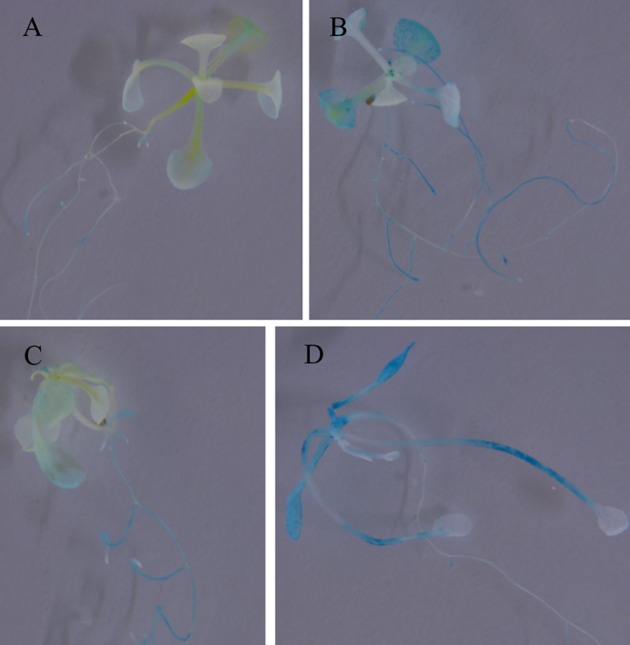

To further investigate the expression characters of ZjSGR, qRT-PCR was carried out. It turns out that ZjSGR expressed most abundantly in zoysiagrass leaves (Figure 1A) and the transcript level was significantly up-regulated under dark treatment and natural senescence progress. In detail, ZjSGR expression level under dark and natural senescence inducements could be more than 11- and 245-folds higher than the initial levels, respectively (Figures 1B,C). Moreover, the results showed that ABA, and MeJA treatments could also induce ZjSGR expression levels to some degree, while SA suppressed the expression of ZjSGR during the 24 h-treatment period (Figures 1D–F). Histochemical analysis revealed that strong GUS activity was found in the leaves of stable transformed ZjSGRPro::GUS Arabidopsis seedlings (Figure 2A). In detail, GUS signal was detected in the vein and petiole of the leaves (Figure 2B) and trichomes (Figure 2C), and also the region of roots (Figure 2D). After ABA, MeJA or dark inducement for 3 days, stronger GUS activity was detected (Figures 3B–D). The GUS assay results indicated that the ZjSGR could be induced by darkness, ABA, and MeJA treatments and it was in accordance with the qRT-PCR results.

Figure 1.

Expression characters of ZjSGR. (A) ZjSGR expression levels in root, stem, and leaf of Zoysia japonica. (B) Expression levels of ZjSGR in Z. japonica leaves at different senescence levels. LS, late senescence; MS, middle senescence; ES, early senescence (C–F) ZjSGR expression levels in Z. japonica exposed to darkness (C), 10 μM ABA (D), 10 μM MeJA (E), and 0.5 mM SA (F).

Figure 2.

GUS staining in 2-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings expressing ZjSGRpro::GUS: (A) whole plant, (B) leaf. (C) Trichomes. (D) Root.

Figure 3.

GUS staining in 2-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings expressing ZjSGRpro::GUS induced by ABA, MeJA, and darkness for 3 days: (A) Control, (B) 10 μM ABA, (C) 10 μM MeJA, (D) darkness.

Overexpression of ZjSGR caused rapid yellowing phenotype in Arabidopsis

To investigate the function of ZjSGR, 35S::ZjSGR:FLAG plasmid was used to transform wild type (Col-0) Arabidopsis plants. In total, more than 40 independent transgenic lines were generated. Two representative T3 lines, SGR-3, andSGR-7, of transgenic lines with higher ZjSGR transcript levels were selected and used throughout the study. Western blot results showed that the target protein enriched in the ZjSGR-overexpressing transgenic Arabidopsis lines (Figure S1). The phenotype observation results showed that ZjSGR overexpression caused rapid yellowing phenotype in transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Figure 3A). In addition, overexpression of ZjSGR resulted in decreased biomass in transgenic Arabidopsis plants compared with control (Figure 3B). The result indicated that the 35S::ZjSGR:FLAG fusion fragment was sufficient to regulate chlorophyll degradation and it could be used as quantified materials for our future studies.

ZjSGR could rescue the stay-green phenotype of nye1-1 under dark inducement

To verify if ZjSGR could rescue the non-yellowing phenotype of the nye1-1 (stay-green mutant), a 1850 bp fragment including the 5′ upstream sequence and the open reading frame was transformed into nye1-1 Arabidopsis plants. More than 20 independent transgenic lines were generated in total and verified by PCR. Two representative T3 lines, Comp-14, and Comp-17, were selected based on the higher expression levels. Detached leaves were cultivated in the 3 mM MES buffer (pH 5.7) under total darkness conditions for 4 days. The results showed that the leaves of the complementary lines were turned to a yellowish color as the control (Col), while the nye1-1 showed a stay-green phenotype (Figure 3C). Correspondingly, the expression level of ZjSGR in the comp-14 and comp-17 detached leaves were up-regulated significantly by darkness treatment (Figure 3D). The complement experiments proved the ZjSGR is a functional homology of AtNYE1, and could accelerate chlorophyll degradation.

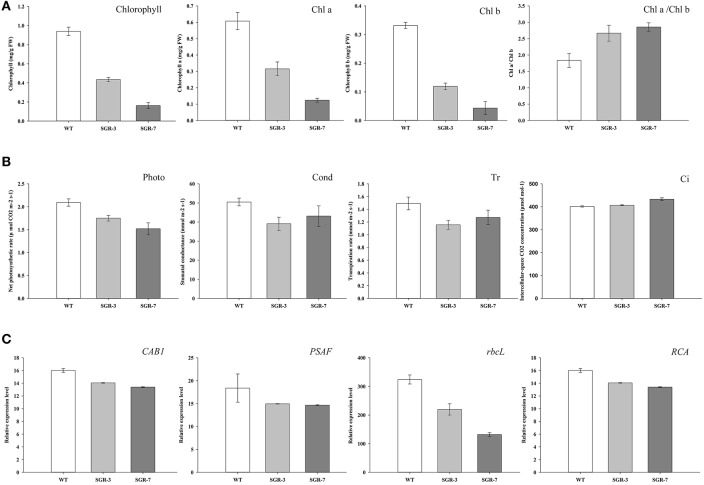

Overexpression of ZjSGR decreased chlorophyll content and impaired photosynthesis in Arabidopsis

During the phenotype observation, a general rapid yellowing character was found in both the ZjSGR-overexpressing and also the complementary transgenic lines (Figure 3). To confirm the roles of ZjSGR in chlorophyll physiological metabolism, total chlorophyll, chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b contents were measured in both ZjSGR-overexpressing and WT Arabidopsis plants. As shown in Figure 5A, total chlorophyll content, chlorophyll a, and chlorophyll b contents were much lower in the representative ZjSGR-overexpressing lines than the control. This is consisted with the yellowing phenotype of the transgenic Arabidopsis plants (Figure 4). Moreover, the ratio of Chl a/b in transgenic plants were higher than the WT plants, significantly.

Figure 4.

Phenotype observation of ZjSGR overexpressing and complementary transgenic T3 lines. (A) SGR-3 and SGR-7 overexpressing lines. (B) Biomass determination of SGR-3 and SGR-7. (C) comp-14 and comp-17 complementary lines. (D) The expression level of ZjSGR in the complementary lines.

Further analysis of the photosynthetic system revealed that the net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance and transpiration rate were lower in the transgenic plants than the control, whereas the intercellular-space CO2 concentration was slightly higher under normal growth conditions (Figure 5B). We then focused on the underlying genetic mechanisms by examining several photosynthesis-related genes in both ZjSGR-overexpressing and WT plants. As shown in Figure 5C, the expression level of the CAB1 (chlorophyll a/b binding gene), PSAF (the photosystem I component encoding gene), rbcL (the Rubisco large submit gene), and RCA (the Rubisco activase gene) were all found significantly lower in the transgenic plants than the control. It indicated that, overexpression of ZjSGR caused decreased chlorophyll content and photosynthetic system efficiency.

Figure 5.

Determination of chlorophyll and photosynthesis in ZjSGR-overexpressing Arabidopsis: (A) Chlorophyll contents, (B) Photosynthesis ability. Photo, the net photosynthetic rate; Cond, stomatal conductance; Ci, intercellular-space CO2 concentration; and Tr, transpiration rate. (C) Expression levels of photosynthetic related genes. CAB1, chlorophyll a/b binding gene; PSAF, the photosystem I component encoding gene; rbcL, the Rubisco large submit gene; RCA, the Rubisco activase gene.

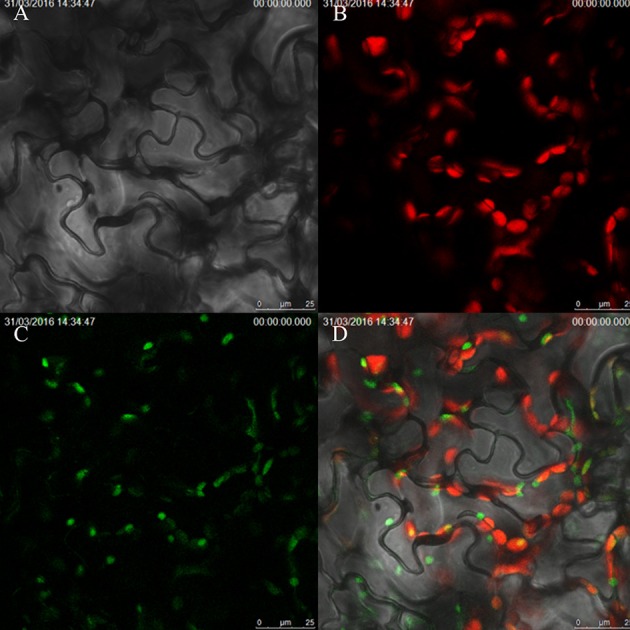

ZjSGR is located in the chloroplast and could impair chloroplast structure in transgenic plants

To explore the subcellular localization pattern of ZjSGR, stable transformed 35S::ZjSGR:YFP Arabidopsis plants leaves were observed using laser confocal scanning microscope. It turned out that the ZjSGR protein was localized in the chloroplasts obviously (Figure 6). However, after observing dozens of slides, a general phenomenon drew our attention that the strong YFP signal were only found in the area where exhibited week chloroplast auto-fluorescence. It led to the hypothesis that overexpression of ZjSGR might impair the chloroplast structure.

Figure 6.

Subcellular localization of ZjSGR in stable transformed Arabidopsis: (A) bright field, (B) chloroplast auto-fluorescence, (C) 35S::ZjSGR:YFP, (D) merged field.

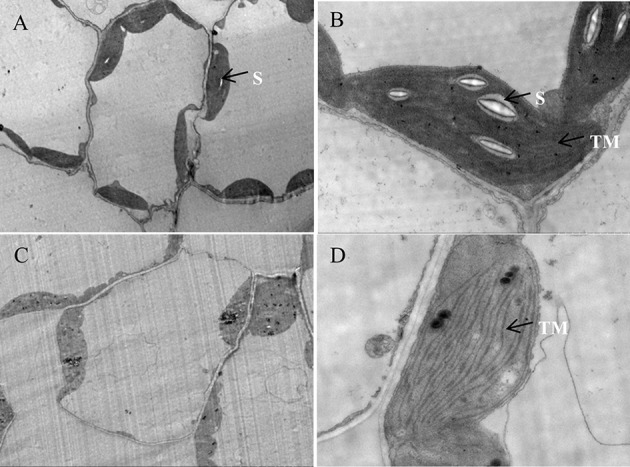

To verify our assumption, the ultrastructure of chloroplasts in both the transient (tobacco) and stable transformed (Arabidopsis) ZjSGR-overexpressing plants were observed using TEM. The results showed that transient overexpression of ZjSGR caused drastic decomposition of chloroplasts in tobacco leaves, corresponding with the interesting subcellular localization pattern (Figure S2). We then focused on the stable transformed Arabidopsis plants with fast yellowing phenotype. The structure of the chloroplasts in WT plants under normal growth conditions maintained a high stability status and didn't show degeneration tendency (Figures 7A,B). However, it exhibited a degeneration of chloroplast structure of the fast yellowing leaves overexpressing ZjSGR under normal growth condition, in which there were fewer starch granule and loose thylakoid membrane (Figures 7C,D). Taken together, these results indicate that there was drastic chloroplast decomposition progress in the ZjSGR-overexpressing leaves which might in turn result in the decreased photosynthesis as well as the interesting subcellular localization character.

Figure 7.

Ultrastructure of chloroplasts in (A,B) wild type, and (C,D) ZjSGR-overexpressing line. S, starch granule; TM, thylakoid membrane.

Global expression analysis revealed that ZjSGR-overexpression accelerated the precocious senescence in developing leaves

In this study, the global gene expression analysis was performed with RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) using ZjSGR-overexpressing Arabidopsis and with WT as control to explore the molecular network of ZjSGR in senescence. Pearson's correlation coefficient was employed to test the reliability of RNA-seq data (Schulze et al., 2012). Correlation coefficients (approximately close to 1) suggested a strong correlation among the biological replicates in WT and ZjSGR-overexpressing plants (Figure S3). Five hundred and ninety five assembled transcripts in total were significantly differently expressed (log2 ≥ 1, q < 0.05; Table S3), of which 499 (83.87%) were up-regulated, whereas 96 (16.13%) down-regulated (Figure S4). To verify the digital expression level of RNA-seq data, qRT-PCR was carried out by investigating the expression levels of 10 representative genes. As shown in Table 2, the qRT-PCR data were generally in accordance with the digital expression levels, confirming that the RNA-seq data were faithful enough for next step analysis.

Table 2.

Verification of DEGs in ZjSGR overexpression transgenic and wild type Arabidopsis plants by qRT-PCR analysis.

| Gene | #ID | SGR/WT (log2 FC) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital expression | qRT-PCR | ||

| SEN1 | AT4G35770 | 2.34 | 2.61 |

| SAG21 | AT4G02380 | 1.24 | 1.43 |

| SAG14 | AT5G20230 | 3.21 | 3.37 |

| NYC1 | AT4G13250 | 1.20 | 1.06 |

| YUC9 | AT1G04180 | −3.83 | −5.03 |

| IAA6 | AT1G52830 | −2.13 | −2.38 |

| IAA29 | AT4G32280 | −3.28 | −3.71 |

| NAC29 | AT1G69490 | 1.84 | 2.55 |

| WRKY6 | AT1G62300 | 1.88 | 2.94 |

| NAC47 | AT3G04070 | 2.33 | 2.94 |

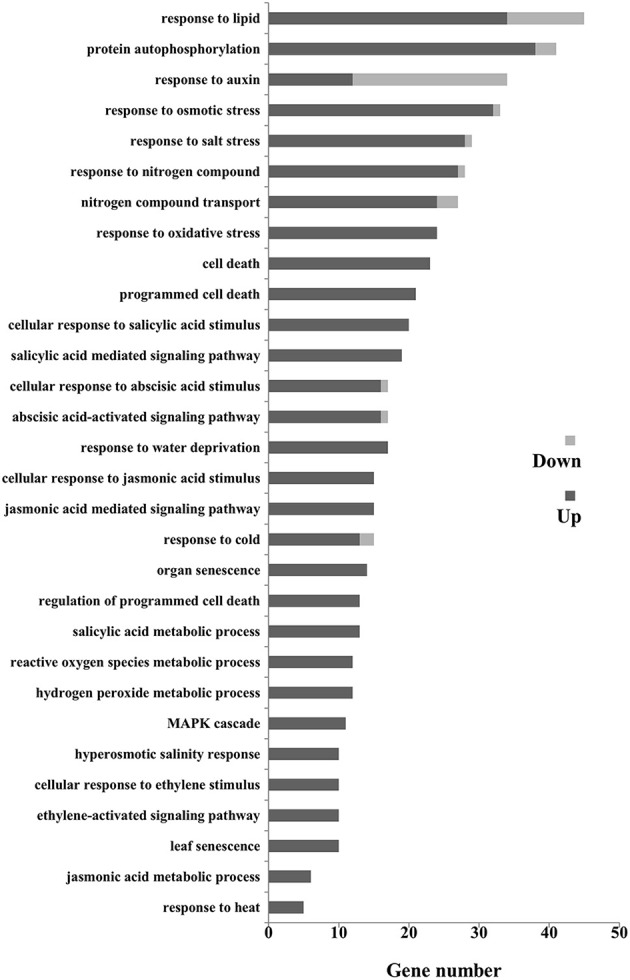

The different expressed genes (DEGs) could be classified into 43 groups (Figure S5) according to the allocated gene ontology (GO) terms (Table S4). Gene Ontology analysis revealed that catalytic activity, binding, and nucleic acid binding transcription factor activity were most overrepresented among the molecular functions; cell part, cell, and organelle were most overrepresented among the cellular component. Further classification in terms of the biological process identified numerous senescence-related genes including nitrogen compound transport, programmed cell death, organ senescence, leaf senescence, phytohormone (auxin, ABA, ET, JA, and SA), and those participated in defense responses (Figure 8). We then focused on the senescence markers of the RNA-seq data. The transcriptional amounts of the 10 putative leaf senescence-associated genes were all up-regulated in ZjSGR-overexpressing plants.

Figure 8.

Gene ontology (Go) classification for senescence related DEGs in WT and ZjSGR-overexpressing Arabidopsis. Only the biological processes were used for GO term analysis.

Additionally, all the DEGs were analyzed to identify the metabolic pathways using the KOBAS system. In total, 78 KEGG pathways were identified and among which the plant hormone signal transduction pathway was significantly enriched (Corrected P < 0.05). To gain insight into the hormone-mediated regulation in senescence, we mapped the DEGs to the Arabidopsis Hormone Database. The results showed that 176 of the 595 DEGs were matched to the SA, ABA, Auxin, JA, and ET associated processes, including response, signaling, biosynthesis and metabolism (Table 3). The largest group was related to SA, and only 2 of the 42 DEGs were down-regulated. In addition, there were only two, one or none down-regulated DEGs found in the ABA, JA, and Ethylene related transcriptional regulations, respectively. Of particular interests, 38 auxin signaling and responsive DEGs was enriched but only 14 of them were up-regulated.

Table 3.

Hormone-related genes differentially expressed in ZjSGR-overexpressing Arabidopsis leaves.

| Hormones | Total number | Up-regulated | Down-regulated |

|---|---|---|---|

| SA | 42 | 40 | 2 |

| Auxin | 38 | 14 | 24 |

| ABA | 35 | 33 | 2 |

| JA | 32 | 31 | 1 |

| Ethylene | 29 | 29 | 0 |

Interestingly, 3.70% (22 of 595) of up- or down- regulated genes encode chloroplast-related proteins (Table S5) in our study. In addition, 54 TF (transcription factor) transcripts from 20 TF families were identified among the 595 DEGs (Table S6). The WRKY, NAC, AP2-EREBP, and MYB families ranked the top four largest families in the RNA-seq data (Table 4). The NAC, WRKY and AP2-EREBP TFs were up-regulated significantly, whereas the AUX/IAA TFs were down-regulated in our study.

Table 4.

Abiotic stress response-related DEGs in wild type control and ZjSGR-overexpressing transgenic plants.

| Gene family | ID | log2FC | padj | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAC | AT1G02220 | 1.8826 | 0.0020227 | NAC domain-containing protein 3 |

| AT1G02230 | 1.7398 | 0.0052586 | NAC domain-containing protein 4 | |

| AT3G04070 | 2.3338 | 0.00083176 | NAC domain-containing protein 10 | |

| AT1G69490 | 1.8425 | 0.000561 | NAC transcription factor 29 | |

| AT5G08790 | 1.5415 | 0.035491 | NAC transcription factor 81 | |

| AT5G39610 | 1.3207 | 0.00018779 | NAC transcription factor 92 | |

| AT3G04060 | 2.1199 | 0.0025559 | NAC transcription factor 100 | |

| WRKY | AT1G62300 | 1.8769 | 0.0018992 | WRKY transcription factor 6 |

| AT5G46350 | 1.7111 | 0.012848 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 8 | |

| AT2G23320 | 1.3137 | 0.038549 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 15 | |

| AT2G30250 | 1.1619 | 0.035656 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 25 | |

| AT5G07100 | 1.4654 | 5.73E-07 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 26 | |

| AT3G01970 | 1.7049 | 3.39E-09 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 45 | |

| AT5G64810 | 1.9589 | 0.00098186 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 51 | |

| AT2G40750 | 1.3998 | 2.93E-05 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 54 | |

| AT3G01080 | 1.6474 | 0.00039729 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 58 | |

| AT1G18860 | 2.0537 | 0.032078 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 61 | |

| AT1G66600 | 2.1873 | 0.02429 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 63 | |

| AT3G56400 | 1.9338 | 0.00016706 | Probable WRKY transcription factor 70 | |

| AP2-EREBP | AT1G75490 | 1.3706 | 0.00018407 | Dehydration-responsive element-binding protein 2D |

| AT3G23240 | 1.7056 | 0.0010819 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor 1B | |

| AT3G50260 | 2.1082 | 0.0071382 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor ERF011 | |

| AT4G17500 | 2.2825 | 0.00030021 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor 1A | |

| AT5G47220 | 1.1646 | 0.0002348 | Ethylene-responsive transcription factor 2 | |

| AT1G25560 | 1.0054 | 0.039972 | AP2/ERF and B3 domain-containing transcription repressor TEM1 | |

| MYB | AT1G71030 | 1.3229 | 0.011338 | MYB transcription factor 3 |

| AT4G05100 | 2.4321 | 0.027624 | MYB transcription factor 39 | |

| AT4G21440 | 2.4943 | 0.016251 | MYB transcription factor 39 | |

| AT1G48000 | 2.1311 | 0.012472 | MYB transcription factor 108 | |

| AT2G18328 | −1.2388 | 0.011778 | Protein RADIALIS-like 4 | |

| AT4G36570 | −1.2784 | 0.022458 | Protein RADIALIS-like 3 | |

| AT5G08520 | −1.1277 | 0.0004582 | Transcription factor DIVARICATA | |

| AT1G01520 | 2.0641 | 0.0017054 | Protein REVEILLE 3 | |

| bHLH | AT2G18300 | −1.2332 | 2.32E-05 | Transcription factor HBI1 |

| AT1G02340 | −1.6919 | 0.039972 | Transcription factor HFR1 | |

| bZIP | AT2G42380 | −1.4225 | 1.30E-05 | Basic leucine zipper 34 |

| AT2G46270 | 1.5046 | 0.030884 | G-box-binding factor 3 | |

| AUX/IAA transcriptional regulator | AT1G04240 | −1.2816 | 0.013065 | Auxin-responsive protein IAA 3 |

| AT1G52830 | −2.1286 | 0.0036074 | Auxin-responsive protein IAA6 | |

| AT4G32280 | −3.2776 | 1.10E-05 | Auxin-responsive protein IAA29 |

Significant differences were determined with FDR < 0.05 and absolute value of log2 FC ≥ 1.

Discussion

The identification of genes that play important roles in controlling the chlorophyll degradation and manipulating senescence progresses provided new access to study plant senescence at molecular level. Herein, a stay-green protein gene was identified from Z. japonica. ZjSGR showed high homologous with the stay-green proteins from other species, indicating its potential roles in manipulating chlorophyll degradation and senescent progresses. The cis-element prediction in the promoter indicated that the expression of ZjSGR might be induced by related environmental conditions and hormones. The qRT-PCR results proved our assumption that the expression level of ZjSGR is in positive correlation with senescent stages. It implied that ZjSGR could be used as an ideal senescence related marker gene. Both the GUS assay and the qRT-PCR results proved that ZjSGR could be induced by dark treatment, and ZjSGR expressed abundantly in the petiole, trichomes, and veins of leaves, suggesting potential roles for ZjSGR in different leaf structures and developments. In addition, the expression of ZjSGR could be up-regulated by ABA and MeJA, and down-regulated by SA application, providing a potential to regulate its transcript through effective management means.

Overexpression and complementation test results showed that overexpression of ZjSGR accelerated chlorophyll degradation and ZjSGR could rescue the stay-green phenotype of nye1-1, suggesting that ZjSGR is a functional homolog of AtNYE1 from Arabidopsis. The total chlorophyll content was decreased in the ZjSGR-overexpressing plants and that was in accordant with the rapid yellowing phenotype. It has been considered that the first step in chlorophyll degradation is the conversion of Chl b–Chl a (Hörtensteiner, 2009). The increased Chl a/b ratio in transgenic Arabidopsis was consisted with the yellowing phenotype in our study. Moreover, overexpression of ZjSGR results in the decreased net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and transpiration rate, indicating that ZjSGR-overexpression impaired photosynthetic system. The slight higher intercellular CO2 concentration also suggested that other photochemical or biochemical activity were probably impaired in transgenic plants (Guo et al., 2004). We further investigated several photosynthesis related genes, including CAB1, PSAF, rbcL, and RCA. The expression levels of all the investigated genes were declined in transgenic plants compared with control, implying the possible involvement of ZjSGR in modulating photosynthetic gene expression directly or indirectly. Taken together, the results proved that overexpression of ZjSGR could accelerate chlorophyll degradation and impair photosynthesis in transgenic Arabidopsis through genetic and biochemical regulation.

The subcellular localization determination proved that ZjSGR was a chloroplast localized protein. This is consistent with the homologous stay-green proteins in A. thaliana (Ren et al., 2007), O. sativa (Park et al., 2007), and M. truncatula (Zhou et al., 2011). TEM observation proved that overexpression of ZjSGR could impair the chloroplasts structure in transgenic Arabidopsis. Previous studies investigated the chloroplast structure in the stay-green mutants under dark inducements, and the results showed that the chloroplast decomposed much slower in the stay-green mutants than the control (Park et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2011). In this study, the interesting subcellular localization pattern inspired us to determine if ZjSGR overexpression could impair the ultrastructure of chloroplasts. The relative fewer starch granules and loose thylakoid membrane indicated that the ZjSGR accelerate the decomposition progress in ZjSGR-overexpressing plants under normal growth conditions. Ultrastructural studies proved that chloroplasts are the first organelle to be decomposed in leaf senescence progress (Dodge, 1970), and resulting in leaf lipids and proteins to be recycled in next step metabolism (Ischebeck et al., 2006). Our results suggested that ZjSGR accelerated chloroplast decomposition and might in turn result in the regulation of downstream metabolism.

A large number of genes are reported differently expressed in the onset and progression of senescence and several networks of gene regulation have been proposed in recent years (Schippers et al., 2015). The RNA-seq data allowed us to further explore the function of ZjSGR from a broader perspective. It revealed that 499 up- and 96 down-regulated genes in total were identified in the ZjSGR-overexpressing plants, implying a preferential role of ZjSGR in regulating gene expression. SEN1, NYC1, SAG21, SAG14, and SAG39 were selected as positive markers to monitor the senescence progress in plants (Jing et al., 2002; Ren et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2011; Jibran et al., 2015; Salleh et al., 2016). The expression levels of all the senescence related DEGs in ZjSGR-overexpressing plants were proved to be up-regulated, implying that the accelerated senescence progress in the transgenic plants. The GO analysis results showed that ZjSGR affected the transcripts of a large portion of genes involved in biotic and abiotic responses in a direct or indirect way, supporting the view that plant defense and senescence extensively co-regulate many genes in these responses (Schenk et al., 2005). The genetic and biochemical regulatory mechanisms of SGR in chlorophyll degradation are largely elusive to date (Zhou et al., 2011; Luo et al., 2013; Sakuraba et al., 2015). In this study, the RNA-seq data revealed that only 3.70% of the DEGs are chloroplast-related genes. It suggests that, rather than directly regulate specific component of the chlorophyll catabolism pathway, ZjSGR may play multi-roles beyond chlorophyll degradation. Because ZjSGR is localized to the chloroplasts, it is possible that the changes in transcript levels resulted from the consequences of secondary effects in chloroplasts decomposition. This result is similar to the microarray analysis of M. truncatula stay-green mutants that proved the extended roles of MtSGR beyond chlorophyll degradation (Zhou et al., 2011).

Senescence involves a rather complex network of hormone signal transduction, such as ABA, MeJA, and Auxin mediated pathways. In our study, KEGG analysis was utilized to explore the metabolic pathways in senescence. The significantly enriched hormone signal transduction pathway suggested its potential roles in senescence. Auxin has been reported to function as a senescence retardant (Mueller-Roeber and Balazadeh, 2014), but its mode of action with respect to senescence is only vaguely defined compared with other hormones such as ABA, MeJA, and GA. Koyama et al. (2013) reported that the transcripts for IAA6 and IAA29 were reduced in precocious leaf senescence. SAUR family genes have been widely used as auxin inducible reporters, and the expression could be induced by auxin rapidly and strongly both in vitro and in vivo (Hou et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012). The RNA-seq results suggested a decreasing trend of auxin response at the transcription level. ABA, Ethylene and JA play important roles in manipulating senescence and environmental stresses in plants (Schippers et al., 2015). The data showed that HAB1 and SNRK2-9 were up-regulated in ABA signal transduction, reflecting a possible negative feedback regulation of ABA metabolism (Wang, 2015), and ABA mediate pathway for stress response in ZjSGR-overexpressing plants (Fujii et al., 2011). This is consistent with our previous study that overexpression of SGR drastically increased the ABA contents in tobacco (Teng et al., 2015). ERF1 and ERF2 are biosynthetic and responsive factors involving in ethylene pathway (Tsai et al., 2014). JAZ9, one member of TIFY family genes, fine-tunes the expression levels of JA-responsive genes in plant stress (Wu et al., 2014). The transcriptional increases of ERF1 and ERF2, and JAZ9 reflected activated ethylene and JA signal transduction contributing to leaf senescence, respectively.

Transcription factors (TFs), by binding to distinct cis-regulatory elements to regulate gene expression, have been proved to be central elements in the senescence networks (Balazadeh et al., 2008). NAC TFs have been reported to function efficiently in chlorophyll degradation and leaf senescence, and actively participant in ABA, MeJA, and ethylene signaling which could act back on leaf senescence (Bu et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2014; Sakuraba et al., 2015; Takasaki et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016). Take the significantly up-regulated AtNAC92 as an example in our study, it was reported to work together with other NAC domain proteins to regulate the expression of many genes in senescence (Balazadeh et al., 2010; Breeze and Buchanan-Wollaston, 2011). AtWRKY6 provides the first evidence that supporting specific WRKY proteins regulate senescence in Arabidopsis (Robatzek and Somssich, 2001). Since then, more and more functional genomic and global transcript studies proved that WRKY TFs could transcriptionally regulate plant senescing processes (Balazadeh et al., 2008; Rinerson et al., 2015). By cross-talking with others, AP2-EREBP TFs are likely to regulate leaf senescence-associated signaling pathways including ROS, ethylene, ABA, and JA (Mizoi et al., 2012). Additionally, MYB TFs were reported to work in plant senescence and various kinds of environmental stresses (Zhang et al., 2011). In this study, the activated senescence in ZjSGR-overexpressing plants may be due, in part, to the up-regulated expression levels of the NAC, WRKY and AP2-EREBP TFs (Koyama, 2014). The global profiling data provides informative data for further study in exploring the molecular regulatory mechanism of SGR and represents an invaluable resource for further investigate senescence processes in plant.

Conclusions

In summary, a stay-green protein gene, ZjSGR, was identified in this study. It could be up-regulated in darkness and natural senescence processes, as well as ABA and MeJA inducements. Functional analysis proved that overexpression of ZjSGR caused rapid yellowing phenotype and could rescue the stay-green phenotype of nye1-1. The chloroplasts localized ZjSGR protein could impair the chloroplasts structure, and decrease chlorophyll content and impaired photosynthesis in Arabidopsis. The functional analysis accompanied with the RNA-seq data proved ZjSGR could play important roles in chlorophyll degradation and senescence progress. This is closely related to the hormone signal transduction and the regulation of a large number of senescence and environmental stress related genes. Our study provides a better understanding of the roles of SGRs, and new insight into the senescence and chlorophyll degradation mechanisms in plants.

Author contributions

KT and YC conceived the study and designed the experiments. KT performed the experiment, and analysed the data with suggestions by ZC, XL, XS, XL, LX, and LH. KT wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (863 Program) (No. 2013AA102607), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31601989 and No. 31672477), Knowledge Innovation Program of Shen Zhen (No. JCYJ20160331151245672), and the Chinese Society of Forestry-Young Talents Development Program. We thank Prof. Hongbo Gao and Prof. Zhixia Hou from Beijing Forestry University for respectively providing the 3302Y vector and Arabidopsis growth chambers. We thank Prof. Benke Kuai from Fudan University for providing the nye1-1 Arabidopsis seeds, and Prof. Jianxiu Liu from the Institute of Botany, Jiangsu Province and Chinese Academy of Sciences for providing the Z. japonica seeds and plugs.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- ABA

abscisic acid

- MeJA

methyl jasmonate

- ET

ethylene

- SA

salicylic acid

- GUS

β-Glucuronidase

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- RNA-seq

RNA sequencing

- DEGs

differently expressed genes

- GO

Gene Ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- TFs

transcript factors.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2016.01894/full#supplementary-material

Western blot analysis of ZjSGR-overexpressing Arabidopsis lines.

Chloroplast structure in (A,B) WT (infiltrated with recombinant agrobacteria as control) and (C,D) transient ZjSGR-overexpressing tobacco leaves (infiltrated with recombinant agrobacteria containing 35S::ZjSGR plasmid).

Pearson correlation between samples.

Volcano plot of the DEGs.

Gene ontology (GO) classification of the DEGs.

Primers used for the RNA-seq data verification.

Cis-regulatory elements of the 5′ up-stream sequence of ZjSGR.

List of the assembled differently expressed transcripts (absolute value of log2 FC ≥ 1, and q < 0.05) in ZjSGR transgenic Arabidopsis compared with WT.

GO analysis list.

Up- or down- regulated genes encoding chloroplast-related proteins.

TFs analysis lists.

References

- Anders S. (2015). HTSeq—A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 31, 166–169. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson A., Keskitalo J., Sjödin A., Bhalerao R., Sterky F., Wissel K., et al. (2004). A transcriptional timetable of autumn senescence. Genome Biol. 5, 1–13. 10.1186/gb-2004-5-4-r24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S., Ria-o-Pachón D. M., Mueller-Roeber B. (2008). Transcription factors regulating leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biol. 10, 63–75. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balazadeh S., Siddiqui H., Allu A. D., Matallana-Ramirez L. P., Caldana C., Mehrnia M., et al. (2010). A gene regulatory network controlled by the NAC transcription factor ANAC092/AtNAC2/ORE1 during salt-promoted senescence. Plant J. Cell. Mol. Biol. 62, 250–264. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04151.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breeze E., Buchanan-Wollaston V. (2011). High-resolution temporal profiling of transcripts during Arabidopsis leaf senescence reveals a distinct chronology of processes and regulation. Plant Cell 23, 873–894. 10.1105/tpc.111.083345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu Q., Jiang H., Li C. B., Zhai Q., Zhang J., Wu X., et al. (2008). Role of the Arabidopsis thaliana NAC transcription factors ANAC019 and ANAC055 in regulating jasmonic acid-signaled defense responses. Cell Res. 18, 756–767. 10.1038/cr.2008.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera M. (2005). Histochemical and fluorometric assays for uidA (GUS) gene detection. Methods Mol. Biol. 286, 203–213. 10.1385/1-59259-827-7:203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christ B., Hörtensteiner S. (2014). Mechanism and significance of chlorophyll breakdown. J. Plant Growth Regul. 33, 4–20. 10.1007/s00344-013-9392-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge J. D. (1970). Changes in chloroplast fine structure during the autumnal senescence of Betula leaves. Ann. Bot. Lond. 34, 817–824. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii H., Verslues P. E., Zhu J. K. (2011). Arabidopsis decuple mutant reveals the importance of SnRK2 kinases in osmotic stress responses in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 1717–1722. 10.1073/pnas.1018367108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo D. P., Guo Y. P., Zhao J. P., Hui L., Yan P., Wang Q. M., et al. (2004). Photosynthetic rate and chlorophyll fluorescence in leaves of stem mustard (Brassica juncea var. tsatsai) after turnip mosaic virus infection. Plant Sci. 168, 57–63. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.07.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland D. R., Arnon D. I. (1950). The Water-Culture Method for Growing Plants Without Soil, Vol. 347 Riverside, CA: Circular California Agricultural Experiment Station. [Google Scholar]

- Hörtensteiner S. (2006). Chlorophyll degradation during senescence. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57, 55–77. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hörtensteiner S. (2009). Stay-green regulates chlorophyll and chlorophyll-binding protein degradation during senescence. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 155–162. 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou K., Wu W., Gan S. S. (2012). SAUR36, a small auxin up RNA gene, is involved in the promotion of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 161, 1002–1009. 10.1104/pp.112.212787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Ye H., Yao R., Tao Z., Xiong L. (2014). OsJAZ9 acts as a transcriptional regulator in jasmonate signaling and modulates salt stress tolerance in rice. Plant Sci. 232, 1–12. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2014.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ischebeck T., Zbierzak A. M., Kanwischer M., Dörmann P. (2006). A salvage pathway for phytol metabolism in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 2470–2477. 10.1074/jbc.M509222200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia N., Liu X., Gao H. (2016). A DNA2 homolog is required for DNA damage repair, cell cycle regulation, and meristem maintenance in plants. Plant Physiol. 171, 318–333. 10.1104/pp.16.00312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jibran R., Sullivan K. L., Crowhurst R., Erridge Z. A., Chagné D., McLachlan A. R., et al. (2015). Staying green postharvest: How three mutations in the Arabidopsis chlorophyll b reductase gene NYC1 delay degreening by distinct mechanisms. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 6849–6862. 10.1093/jxb/erv390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing H. C., Sturre M. J., Hille J., Dijkwel P. P. (2002). Arabidopsis onset of leaf death mutants identify a regulatory pathway controlling leaf senescence. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 32, 51–63. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01400.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D., Pertea G., Trapnell C., Pimentel H., Kelley R., Salzberg S. L. (2013). TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14:R36. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Hong S. H., Kim Y. W., Lee I. H., Jun J. H., Phee B. K., et al. (2014). Gene regulatory cascade of senescence-associated NAC transcription factors activated by ETHYLENE-INSENSITIVE2-mediated leaf senescence signalling in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 4023–4036. 10.1093/jxb/eru112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson L. L., Tibbitts T. W., Edwards G. E. (1977). Measurement of ozone injury by determination of leaf chlorophyll concentration. Plant Physiol. 60, 606–608. 10.1104/pp.60.4.606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T. (2014). The roles of ethylene and transcription factors in the regulation of onset of leaf senescence. Front. Plant Sci. 5:650. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T., Nii H., Mitsuda N., Ohta M., Kitajima S., Ohme-Takagi M., et al. (2013). A regulatory cascade involving class II ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR transcriptional repressors operates in the progression of leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 162, 991–1005. 10.1104/pp.113.218115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Gao J., Yao L., Ren G., Zhu X., Gao S., et al. (2016). The role of ANAC072 in the regulation of chlorophyll degradation during age-and dark-induced leaf senescence. Plant Cell Rep. 35, 1729–1741. 10.1007/s00299-016-1991-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 −ΔΔCT method. Methods 25, 402–408. 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Z., Zhang J., Li J., Yang C., Wang T., Ouyang B., et al. (2013). A STAY-GREEN protein SlSGR1 regulates lycopene and β-carotene accumulation by interacting directly with SlPSY1 during ripening processes in tomato. New Phytol. 198, 442–452. 10.1111/nph.12175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDuff J., Raistrick N., Humphreys M. (2002). Differences in growth and nitrogen productivity between a stay-green genotype and a wild-type of Lolium perenne under limiting relative addition rates of nitrate supply. Physiol. Plant. 116, 52–61. 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1160107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao X., Cai T., Olyarchuk J. G., Wei L. (2005). Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics 21, 3787–3793. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Pang C., Fan S., Song M., Wei H., Yu S. (2015). Global analysis of the Gossypium hirsutum L. Transcriptome during leaf senescence by RNA-Seq. BMC Plant Biol. 15:43. 10.1186/s12870-015-0433-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoi J., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. (2012). AP2/ERF family transcription factors in plant abiotic stress responses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1819, 86–96. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller-Roeber B., Balazadeh S. (2014). Auxin and its role in plant senescence. J. Plant Growth Regul. 33, 21–33. 10.1007/s00344-013-9398-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. Y., Yu J. W., Park J. S., Li J., Yoo S. C., Lee N. Y., et al. (2007). The senescence-induced staygreen protein regulates chlorophyll degradation. Plant Cell 19, 1649–1664. 10.1105/tpc.106.044891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton A. J., Reicher Z. J. (2007). Zoysiagrass species and genotypes differ in their winter injury and freeze tolerance. Crop Sci. 47, 1619–1627. 10.2135/cropsci2006.11.0737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G., An K., Liao Y., Zhou X., Cao Y., Zhao H., et al. (2007). Identification of a novel chloroplast protein AtNYE1 regulating chlorophyll degradation during leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 144, 1429–1441. 10.1104/pp.107.100172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G., Zhou Q., Wu S., Zhang Y., Zhang L., Huang J., et al. (2010). Reverse genetic identification of CRN1 and its distinctive role in chlorophyll degradation in Arabidopsis. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52, 496–504. 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2010.00945.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinerson C. I., Scully E. D., Palmer N. A., Donze-Reiner T., Rabara R. C., Tripathi P., et al. (2015). The WRKY transcription factor family and senescence in switchgrass. BMC Genomics 16:912. 10.1186/s12864-015-2057-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robatzek S., Somssich I. E. (2001). A new member of the Arabidopsis WRKY transcription factor family, AtWRKY6, is associated with both senescence- and defence-related processes. Plant J. 28, 123–133. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01131.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuraba Y., Han S. H., Lee S. H., Hörtensteiner S., Paek N. C. (2015). Arabidopsis NAC016 promotes chlorophyll breakdown by directly upregulating STAYGREEN1 transcription. Plant Cell Rep. 35, 155–166. 10.1007/s00299-015-1876-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salleh F. M., Mariotti L., Spadafora N. D., Price A. M., Picciarelli P., Wagstaff C., et al. (2016). Interaction of plant growth regulators and reactive oxygen species to regulate petal senescence in wallflowers (Erysimum linifolium). BMC Plant Biol. 16:77. 10.1186/s12870-016-0766-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk P. M., Kazan K., Rusu A. G., Manners J. M., Maclean D. J. (2005). The SEN1 gene of Arabidopsis is regulated bysignals that link plant defence responses and senescence. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 43, 997–1005. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schippers J. H., Schmidt R., Wagstaff C., Jing H. C. (2015). Living to die and dying to live: the survival strategy behind leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 169, 914–930. 10.1104/pp.15.00498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze S. K., Kanwar R., Gölzenleuchter M., Therneau T. M., Beutler A. S. (2012). SERE: single-parameter quality control and sample comparison for RNA-Seq. BMC Genomics 13:524. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasaki H., Maruyama K., Takahashi F., Fujita M., Yoshida T., Nakashima K., et al. (2015). SNAC-As, stress-responsive NAC transcription factors, mediate ABA-inducible leaf senescence. Plant J. 84, 1114–1123. 10.1111/tpj.13067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H., Hirakawa H., Kosugi S., Nakayama S., Ono A., Watanabe A., et al. (2016). Sequencing and comparative analyses of the genomes of zoysiagrasses. DNA Res. 23, 171–180. 10.1093/dnares/dsw006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng K., Chang Z. H., Xiao G. Z., Guo W. E., Xu L. X., Chao Y. H., et al. (2015). Molecular cloning and characterization of a chlorophyll degradation regulatory gene (ZjSGR) from Zoysia japonica. Genetics Mol. Res. 15:gmr8176. 10.4238/gmr.15028176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng K., Tan P., Xiao G., Han L., Chang Z., Chao Y. (2016). Heterologous expression of a novel Zoysia japonica salt-induced glycine-rich RNA-binding protein gene, ZjGRP, caused salt sensitivity in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1007/s00299-016-2068-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai K. J., Chou S. J., Shih M. C. (2014). Ethylene plays an essential role in the recovery of Arabidopsis during post-anaerobiosis reoxygenation. Plant Cell Environ. 37, 2391–2405. 10.1111/pce.12292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. (2015). ABA signalling is fine-tuned by antagonistic HAB1 variants. Nat. Commun. 6:8138. 10.1038/ncomms9138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S., Du Z., Gao F., Ke X., Li J., Liu J., et al. (2015). Global transcriptome profiles of ‘meyer’ zoysiagrass in response to cold stress. PLoS ONE 10:e0131153. 10.1371/journal.pone.0131153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingler A., Roitsch T. (2008). Metabolic regulation of leaf senescence: interactions of sugar signalling with biotic and abiotic stress responses. Plant Biol. 10(Suppl. 1), 50–62. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00086.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Liu S., He Y., Guan X., Zhu X., Cheng L., et al. (2012). Genome-wide analysis of SAUR gene family in Solanaceae species. Gene 509, 38–50. 10.1016/j.gene.2012.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Zhang M., Zhang X., Han L. B. (2015). Cold Acclimation treatment-induced changes in abscisic acid, cytokinin, and antioxidant metabolism in Zoysiagrass (Zoysia japonica). Hortscience 50, 1075–1080. Available online at: http://hortsci.ashspublications.org/content/50/7/1075.short [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. D., Seo P. J., Yoon H. K., Park C. M. (2011). The Arabidopsis NAC transcription factor VNI2 integrates abscisic acid signals into leaf senescence via the COR/RD genes. Plant Cell 23, 2155–2168. 10.1105/tpc.111.084913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Ju H. W., Chung M. S., Huang P., Ahn S. J., Kim C. S. (2011). The R-R-type MYB-like transcription factor, AtMYBL, is involved in promoting leaf senescence and modulates an abiotic stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 52, 138–148. 10.1093/pcp/pcq180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C., Han L., Pislariu C., Nakashima J., Fu C., Jiang Q., et al. (2011). From model to crop: functional analysis of a STAY-GREEN gene in the model legume Medicago truncatula and effective use of the gene for alfalfa improvement. Plant Physiol. 157, 1483–1496. 10.1104/pp.111.185140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Western blot analysis of ZjSGR-overexpressing Arabidopsis lines.

Chloroplast structure in (A,B) WT (infiltrated with recombinant agrobacteria as control) and (C,D) transient ZjSGR-overexpressing tobacco leaves (infiltrated with recombinant agrobacteria containing 35S::ZjSGR plasmid).

Pearson correlation between samples.

Volcano plot of the DEGs.

Gene ontology (GO) classification of the DEGs.

Primers used for the RNA-seq data verification.

Cis-regulatory elements of the 5′ up-stream sequence of ZjSGR.

List of the assembled differently expressed transcripts (absolute value of log2 FC ≥ 1, and q < 0.05) in ZjSGR transgenic Arabidopsis compared with WT.

GO analysis list.

Up- or down- regulated genes encoding chloroplast-related proteins.

TFs analysis lists.