Abstract

A fundamental motif in canonical nucleic acid structure is the base pair. Mutations that disrupt base pairs are typically destabilizing, but stability can often be restored by a second mutation that replaces the original base pair with an isosteric variant. Such concerted changes are a way to identify helical regions in secondary structures and to identify new functional motifs in sequenced genomes. In principle, such analysis can be extended to non-canonical nucleic acid structures, but this approach has not been utilized because the sequence requirements of such structures are not well understood. Here we investigate the sequence requirements of a G-quadruplex that can both bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions. Characterization of all 256 variants of the central tetrad in this structure indicates that certain mutations can compensate for canonical G-G-G-G tetrads in the context of both GTP-binding and peroxidase activity. Furthermore, the sequence requirements of these two motifs are significantly different, indicating that tetrad sequence plays a role in determining the biochemical specificity of G-quadruplex activity. Our results provide insight into the sequence requirements of G-quadruplexes, and should facilitate the analysis of such motifs in sequenced genomes.

INTRODUCTION

G-quadruplexes are four-stranded nucleic acid structures stabilized by G-G-G-G tetrads (1–2). Growing evidence suggests that these structures play widespread biological roles in eukaryotes (3–5). Cellular processes proposed to be regulated by DNA or RNA G-quadruplexes include transcription (6–7), RNA processing (8), translation (9–11), and mRNA localization (12). Biochemical studies have also started to reveal details of the mechanisms by which G-quadruplexes promote their cellular functions. More than 30 proteins have been identified that specifically interact with G-quadruplexes in various ways, including examples that bind G-quadruplexes, mediate the folding of G-quadruplexes, and promote the unfolding of G-quadruplexes (13–14). A handful of cellular cofactors that bind G-quadruplexes have also been identified (15–18). G-quadruplexes that promote several types of peroxidase reactions in the presence of hemin and hydrogen peroxide have also been reported (19–20). Consistent with the idea that they play widespread biological roles, G-quadruplexes occur frequently in the genomes of higher eukaryotes. For example, initial bioinformatic studies of G-quadruplexes showed that at least 400 000 sequences with the potential to form such a structure occur in the human genome alone (21–22). The development of G-quadruplex specific antibodies has greatly facilitated the study of these structures, especially in the context of cells (23–24). For example, experiments using fluorescent antibodies specific for G-quadruplexes have provided additional evidence that such structures form in cellular DNA and RNA (25–28). These methods have also provided insight into regulatory roles of G-quadruplexes. For instance, cellular expression of a G-quadruplex antibody alters global gene expression in a way that can be rationalized based on the presence of G-quadruplexes in promoters (29). Moreover, such experiments have provided additional quantitative information about G-quadruplexes in cells. For example, high-throughput sequencing of genomic fragments purified using a G-quadruplex antibody suggests that at least 700 000 of these structures exist in human cells, including more than 450 000 examples not previously detected by bioinformatics (26,30). Taken together, these studies provide strong evidence that G-quadruplexes play important roles in higher eukaryotes.

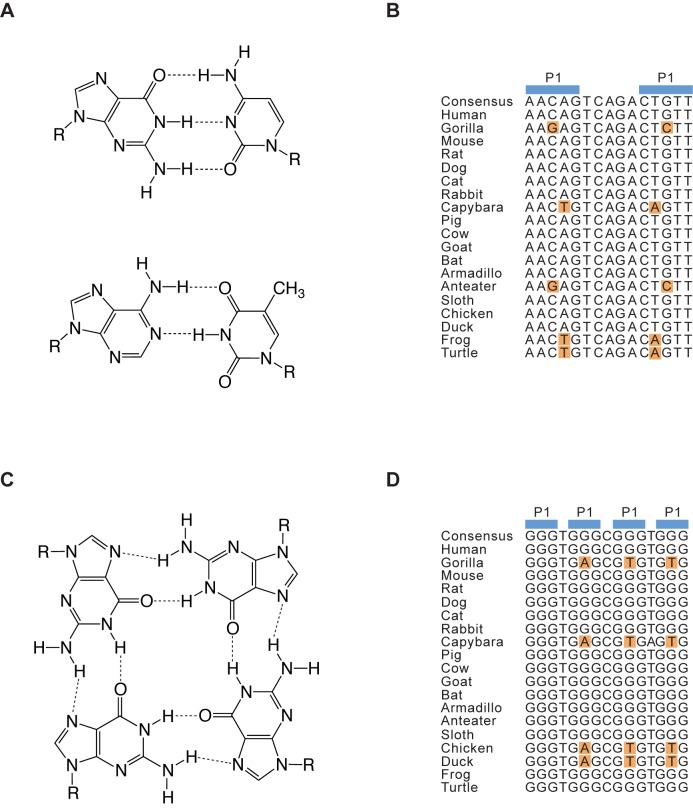

Although G-quadruplexes occur frequently in genomes, the number of biologically relevant examples is not known. Answering this important question could be facilitated by bioinformatic methods capable of identifying the examples in sequenced genomes most likely to be functional. An approach widely used to address this issue for nucleic acid motifs with conventional duplex structures is comparative sequence analysis (Figure 1) (31–35). This method is based in part on the observation that mutational changes at certain positions in sequence alignments of conserved nucleic acid secondary structures typically occur only in the presence of specific mutational changes at a second position in the alignment (Figure 1B). Such concerted changes, called covariations, occur because base pairs of roughly the same size and shape can form from different combinations of nucleotides (Figure 1A) (36–37). Comparative sequence analysis is the most accurate way to predict nucleic acid secondary structures. For example, 97% of the base pairs in the crystal structures of 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA were correctly identified using this method (34). Comparative sequence analysis has also been used to identify new examples of conserved RNA secondary structures in sequenced genomes. Virtually all known riboswitches were identified using this method (38–39), and comparative sequence analysis has also been applied to identify new variants of known motifs such as the hammerhead and HDV ribozymes (40).

Figure 1.

Comparative sequence analysis of duplex and G-quadruplex structures. (A) Chemical structures of G-C and A-T base pairs. (B) Hypothetical sequence alignment of an evolutionary conserved hairpin. Covariations in the alignment are shown in orange. (C) Chemical structure of a G-G-G-G tetrad. (D) Hypothetical sequence alignment of an evolutionary conserved G-quadruplex. Covariations in the alignment based on those identified in this work are shown in orange.

Because comparative sequence analysis is such a powerful method when applied to the characterization of duplex nucleic acid structures, we hypothesized that this approach would also be a useful way to identify biologically relevant G-quadruplexes in sequenced genomes (Figure 1C and D). Before we could test this hypothesis, however, the types of compensatory mutations that could occur in the tetrads of G-quadruplexes needed to be characterized. In the work described here we have identified some of these mutations for G-quadruplexes that bind guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP) and promote peroxidase reactions. To do this, the central tetrad in a reference G-quadruplex was mutated and each of the 256 possible sequence variants was tested for the ability to bind GTP (17) and to promote a model peroxidase reaction in the presence of hemin and hydrogen peroxide (19). The ability of the most active of these variants to form G-quadruplex structures was also investigated using circular dichroism spectroscopy (41–42). These experiments revealed that, when viewed from the perspective of biochemical activity, G-quadruplex structures are more tolerant to mutations than previously thought. Moreover, the sequence requirements of G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions are significantly different, indicating that tetrad sequence plays an important role in determining the biochemical specificity of G-quadruplex activity. The information from these mutagenesis experiments was used as a starting point to develop sequence models for G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions, and these models were used to identify conserved examples of both motifs in the human genome. Taken together, our experiments provide new insights into the sequence requirements of G-quadruplexes and highlight the importance of developing a comprehensive catalog of sequence models for G-quadruplexes with various biochemical activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

Desalted DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Sigma. Oligonucleotides were resuspended in Milli-Q water at a concentration of 100 μM and used without additional purification. Truncated products could not be detected when oligonucleotides were analyzed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Stock solutions were stored at −20°C and thawed at room temperature before use. MgCl2 (catalog number 63068), KCl (catalog number 60128), and HEPES buffer (catalog number 54457) were purchased from Sigma. Stock solutions were prepared by dissolving in Milli-Q water and filtered using 0.22 μm filters (VWR catalog number 514-0334). The pH of HEPES solutions were adjusted using KOH (catalog number 221473) purchased from Sigma. Hemin (H9039) was purchased from Sigma. Stock solutions at a concentration of 1.5 mM were prepared by dissolving in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma D8418) for 1 h at room temperature. These solutions were stored in the dark at −20°C and used within one week. ABTS (A1888) was purchased from Sigma. Stock solutions at a concentration of 50 mM were prepared by dissolving in Milli-Q water. Solutions were stored in the dark at 4°C and used within one day. Hydrogen peroxide (516813) and Triton X-100 (T8787) were purchased from Sigma. Unlabeled GTP (catalog number NU-1014) was purchased from Jena BioSciences, and 32P-γ-GTP (185 TBq/mmol) was purchased from MGP (catalog number SCP-402).

Analysis of dimer formation

Oligonucleotides were radiolabeled with 32P-γ-ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase as previously described.17 Following phenol extraction, unreacted adenosine triphosphate (ATP) was removed from labeling reactions using SigmaSpin columns (Sigma catalog number S5059) and the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. In a typical experiment, stock solutions (100 μM of the unlabeled oligonucleotide and ≤2.5 μM of the radiolabeled oligonucleotide) were thawed at room temperature. After vortexing, 2 μl of unlabeled oligonucleotide was mixed with 5.5 μl of water and 2.5 μl of radiolabeled oligonucleotide. The solution was then heated at 65°C for 5 min, cooled at room temperature for 5 min and mixed with 10 μl of a solution containing 5 μl of 4× aptamer buffer (4 mM MgCl2, 800 mM KCl, 80 mM HEPES, pH 7.1), 4.9 μl of Milli-Q water and 0.1 μl of 2 μM GTP. Final concentrations were 10 μM of unlabeled oligonucleotide and ≤0.3 μM of radiolabeled oligonucleotide in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.1, and 10 nM GTP. After incubating for 30 min, samples were purified using Centri-Sep spin columns (Princeton Separations catalog number CS-901) and the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. After centrifugation, 2 μl of the flowthrough was spotted onto filter paper and analyzed using a Typhoon FLA 9500 phosphorimager. In some cases, samples were also analyzed by native PAGE. To do this, 4 μl of 6× gel loading buffer (60% w/v glycerol, 0.15% w/v bromophenol blue, and 0.15% w/v xylene cyanol) was added to each 20 μl reaction and 5 μl aliquots were analyzed on 10% PAGE gels containing 1× Tris-Borate-EDTA buffer (TBE) and 5 mM KCl. Gels were run at 300 V for 30 min in a buffer containing 1× TBE and 5 mM KCl.

GTP-binding assays

In a typical GTP-binding assay, a 100 μM DNA stock solution (stored at −20°C) was thawed at room temperature. After vortexing, 2 μl was mixed with 8 μl of Milli-Q water. The solution was then heated at 65°C for 5 min, cooled at room temperature for 5 min and mixed with 10 μl of a solution containing 5 μl of 4× aptamer buffer (4 mM MgCl2, 800 mM KCl, 80 mM HEPES, pH 7.1), 4.9 μl of Milli-Q water, and 0.1 μl of 2 μM 32P-γ-GTP. Final concentrations were 10 μM DNA in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.1, and 10 nM 32P-γ-GTP. After incubating for 30 min, unbound GTP was removed using a Centri-Sep spin column (Princeton Separations catalog number CS-901) and the protocol recommended by the manufacturer. After centrifugation, 2 μl of the flowthrough was spotted onto filter paper and analyzed using a Typhoon FLA 9500 phosphorimager. GTP-binding activity was expressed relative to that of the reference construct, which was measured in every experiment. The 32P-γ-GTP bound by a random sequence control oligonucleotide was typically undetectable under the conditions of this assay.

Peroxidase assays

In a typical peroxidase assay, a 100 μM DNA stock solution (stored at −20°C) was thawed at room temperature. After vortexing, 5 μl was mixed with 7.5 μl of Milli-Q water. This solution was heated at 65°C for 5 min, and cooled at room temperature for 5 min. It was then mixed with 12.5 μl of a solution containing 6.25 μl of 4× peroxidase buffer (4 mM MgCl2, 800 mM KCl, 80 mM HEPES pH 8, 0.2% Triton X-100), 5.75 μl Milli-Q water, and 0.5 μl of 50 μM hemin (made by diluting a 1.5 mM hemin stock solution into DMSO). After incubating for 30 min at room temperature in the dark, this was mixed with 20 μl of a solution containing 6.25 μl 4× peroxidase buffer (see above), 5 μl of 50 mM ABTS, and 8.75 μl of water. The resulting solution was transferred to a clear half-area 96-well plate (Corning; Sigma catalog number CLS3695). After adding 5 μl of 6 mM hydrogen peroxide, absorption at 414 nm was measured with a plate reader (Tecan Infinite M1000). Final concentrations were 10 μM DNA in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 8, 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.5 μM hemin, 1% DMSO, 5 mM ABTS, and 600 μM H2O2. Peroxidase activity was expressed relative to that of the reference construct, which was measured in every experiment.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

In a typical circular dichroism experiment, a 100 μM DNA stock solution (stored at −20°C) was thawed at room temperature. After vortexing, 20 μl was mixed with 80 μl of Milli-Q water. This solution was heated at 65°C for 5 min, and cooled at room temperature for 5 minutes. It was then mixed with 100 μl of a solution containing either 50 μl of 4× aptamer buffer (4 mM MgCl2, 800 mM KCl, 80 mM HEPES, pH 7.1), 49 μl Milli-Q water, and 1 μl of 2 μM unlabeled GTP or 50 μl of 4× peroxidase buffer (4 mM MgCl2, 800 mM KCl, 80 mM HEPES pH 8, 0.2% Triton X-100) and 50 μl Milli-Q water. Final conditions were 10 μM DNA in a buffer containing either 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.1, and 10 nM unlabeled GTP or 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 8, and 0.05% Triton X-100. Some reactions also contained 0.5 μM hemin and 1% DMSO. After incubating for 30 minutes, ECD spectra were measured on a Jasco 815 spectropolarimeter over a spectral range of 200 to 350 nm (for measurements made in aptamer buffer), 210 to 350 nm (for measurements made in peroxidase buffer), or 225 to 400 nm (for measurements made in peroxidase buffer containing hemin). Measurements were made in a quartz cell with a 0.1 cm path length using a scanning speed of 10 nm/min, a response time of 8 s, standard instrument sensitivity and three spectra accumulations. After a baseline correction, spectra were expressed in terms of differential optical density.

Bioinformatics

The human reference genome sequence (build hg19) was scanned using the program PatScan (43) for all 17 nucleotide motifs consistent with the sequence requirements of GTP-binding or peroxidase activity using the models shown in Figure 7. Both strands were included in the search, and all overlapping hits were included. Next, the ‘multiz100way’ multi-species alignment of the human reference genome plus 99 other vertebrate genome sequences was downloaded from UCSC (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTrackUi?db=hg19&g=cons100way), and the corresponding region of this alignment was retrieved for each of the hits identified above. Each of these small alignments was optimized locally by realignment using the Smith-Waterman algorithm (44) with parameters set to strongly penalize gaps (the ‘gap_open’ parameter was set to 1000). Next, each of the 99 non-human species was examined to see whether its homologous sequence (extracted from the optimized alignment) was also compatible with the activity of the human sequence, according to the Figure 7 rules. For each hit, the maximal clade was identified in which all species in the clade contained a homologous sequence retaining compatibility with the activity of the human sequence. The number of hits in each maximal clade is shown in Figure 8A for our sequence models of GTP binding and peroxidase activity. For each hit, a consensus sequence within the maximal clade of the hit was determined by taking the most common nucleotide at each position. For each species in the maximal clade, the number of mutations with respect to this consensus sequence was calculated, as well as the number of those mutations occurring within the four positions of the tetrad. Figure 8B and C show maximal-clade alignments, consensus sequences and highlighted tetrad mutations for two example hits.

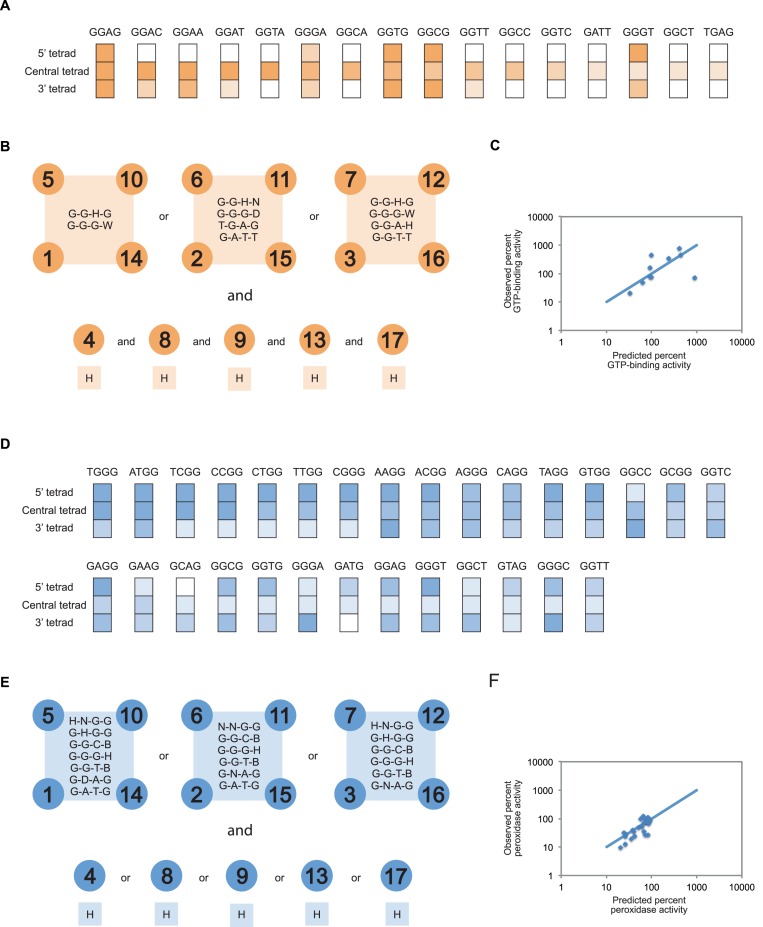

Figure 7.

Sequence models for G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions. (A) Comparing the effects of mutations in the 5’, central and 3’ tetrad on the ability of the reference construct to bind GTP. The color scheme used to indicate the activity of each mutant matches that in Figure 3. (B) Sequence model for G-quadruplexes that bind GTP. 5’ tetrad = positions 1, 5, 10 and 14; central tetrad = positions 2, 6, 11 and 15; 3’ tetrad = positions 3, 7, 12 and 16; spacer nucleotides = 4, 8, 9, 13 and 17. (C) Expected and observed activities of 10 randomly chosen sequences that satisfy the requirements of our model. The blue line indicates the relationship if expected and observed activities were identical, and was calculated by assuming that spacer sequence does not influence activity. GTP-binding activity is expressed relative to that of the reference construct. Experiments were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.1 and 10 nM 32P-γ-GTP. (D) Comparing the effects of mutations in the 5’, central and 3’ tetrad on the ability of the reference construct to promote peroxidase reactions. The color scheme used to indicate the activity of each mutant matches that in Figure 3. (E) Sequence model for G-quadruplexes that promote peroxidase reactions. 5’ tetrad = positions 1, 5, 10 and 14; central tetrad = positions 2, 6, 11 and 15; 3’ tetrad = positions 3, 7, 12 and 16; spacer nucleotides = 4, 8, 9, 13 and 17. (F) Expected and observed activities of 30 randomly chosen sequences that satisfy the requirements of our model. The blue line indicates the relationship if expected and observed activities were identical, and was calculated by assuming that spacer sequence does not influence activity. Peroxidase activity is expressed relative to that of the reference construct. Experiments were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 8, 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.5 μM hemin, 1% DMSO, 5 mM ABTS and 600 μM H2O2. In panels (B) and (E), the IUPAC nucleotide code was used to indicate the nucleotides that are permitted to occur at variable positions in each sequence model. W = A or T; H = A, C or T; D = A, G or T; B = C, G or T; N = A, C, G or T.

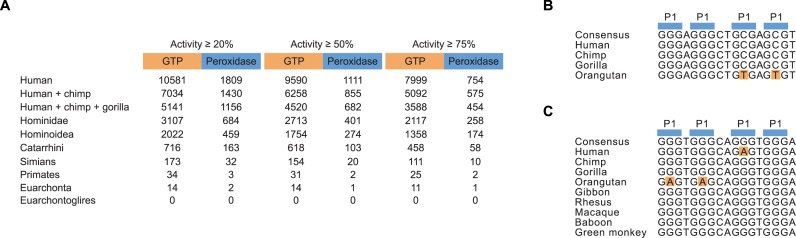

Figure 8.

Identification of evolutionary conserved G-quadruplexes in the human genome that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions. (A) Abundance and evolutionary conservation of G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions in various vertebrate clades. (B) Sequence alignment of an evolutionary conserved G-quadruplex that contains mutations in a tetrad consistent with the sequence requirements of GTP-binding activity. This example occurs in an intergenic region on chromosome 4. (C) Sequence alignment of an evolutionary conserved G-quadruplex that contains mutations in a tetrad consistent with the sequence requirements of peroxidase activity. This example occurs in an intron shared by two genes on chromosome 10.

RESULTS

Tetrad identification in G-quadruplex forming sequences

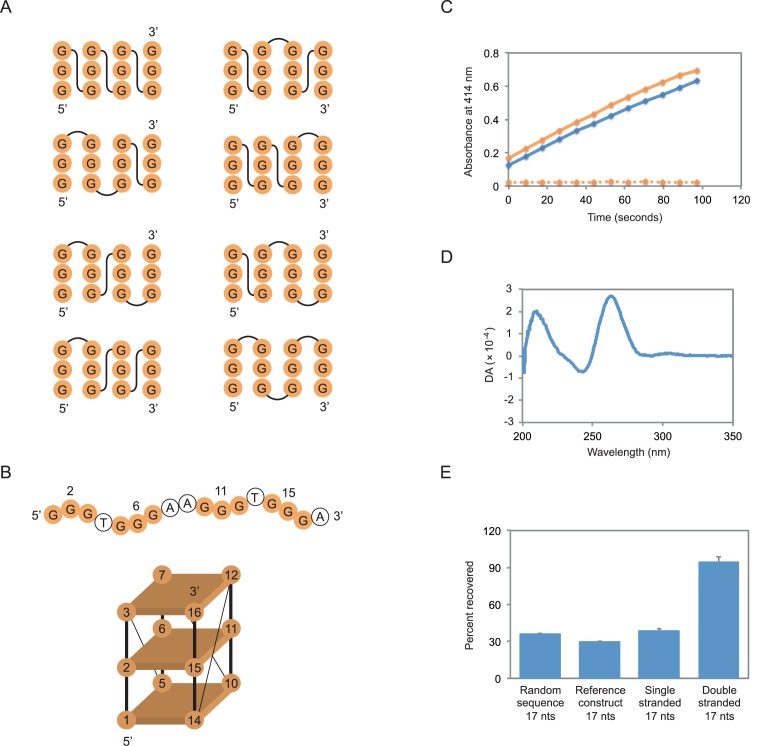

In the initial stage of the project we performed pilot experiments to identify an appropriate reference construct for site-directed mutagenesis. The most important requirement of this construct was that it contained at least one tetrad made up of nucleotides that could be unambiguously identified in the primary sequence. For this reason, we focused on sequences that contained sets of exactly three guanosines. Although such sequences can form structures with parallel, antiparallel or mixed-strand topologies (Figure 2A) (2), for every structure with three tetrads the central nucleotide in each set of guanosines will also be in the central tetrad of the G-quadruplex. A second requirement was that this construct could bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions efficiently. A previously characterized sequence with sets of guanosines of the correct size appeared to be a promising candidate (Figure 2B) (17). This sequence binds GTP 700-fold better than a random sequence control oligonucleotide of the same length (17). It also promotes the oxidation of 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS) with a rate enhancement of approximately 150-fold under the conditions of our assay (Figure 2C). As is the case for other G-quadruplexes that bind GTP (17) and promote peroxidase reactions (45–48), the circular dichroism spectrum of this sequence suggests that it adopts a parallel-strand topology (Figure 2D). A final requirement was that the reference construct did not form higher order structures (such as dimers) that could complicate interpretation of mutational effects. The extent to which the reference construct was retained in a gel filtration column was similar to that of a typical oligonucleotide of its size (determined by analyzing the retention of a 17 nucleotide random sequence pool), but significantly greater than that of a 17 nucleotide duplex (Figure 2E). Furthermore, no evidence for such structures was observed when the reference construct was analyzed by native PAGE (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Mutagenesis of a tetrad in a DNA G-quadruplex with GTP-binding and peroxidase activity. (A) Topological isoforms of G-quadruplexes formed from different combinations of parallel and antiparallel strands. (B) Primary sequence and possible structure of the reference construct used in these experiments. Mutated positions in the central tetrad are numbered. Note that our experiments do not indicate which strands are next to one another in this structure. (C) Peroxidase activity of the reference construct using the substrate ABTS. Solid orange curve = the most active previously described construct (ATTGGGAGGGATTGGGTGGG); solid blue curve = the reference construct; dotted orange curve = a 17 nucleotide random sequence pool. (D) Circular dichroism spectrum of the reference construct. DA = differential absorption. (E) Retention of the reference construct in a gel filtration column compared to single and double-stranded markers. Random sequence = a 17 nucleotide random sequence pool; single stranded = a randomly generated, 17 nucleotide oligonucleotide with the sequence GACTGCCTCGTCACGAT; double stranded = a mix of the single-stranded oligonucleotide GACTGCCTCGTCACGAT and its reverse complement. The experiment in panel (C) was performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 8, 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.5 μM hemin, 1% DMSO, 5 mM ABTS, and 600 μM H2O2. Experiments in panels (D) and (E) were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.1, and 10 nM unlabeled GTP. In panel (E), reported values represent the average of three experiments and error bars indicate one standard deviation.

Identification of mutant tetrads compatible with G-quadruplex formation

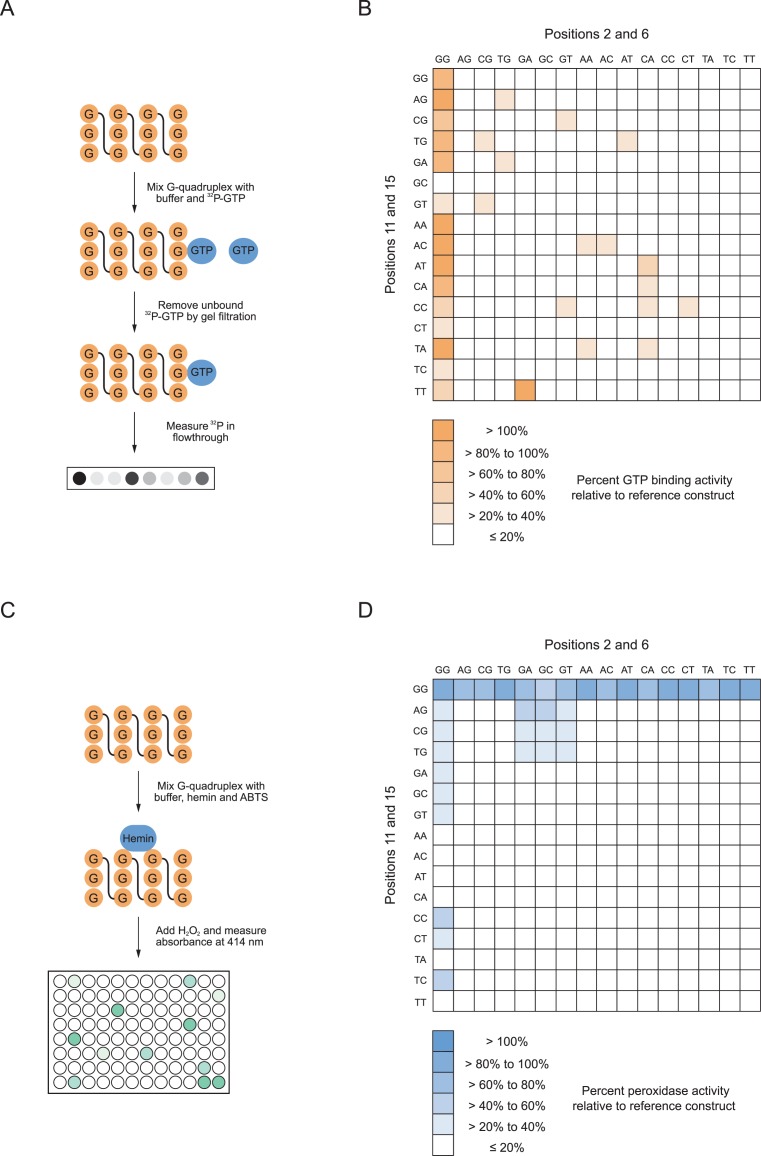

To characterize the sequence requirements of this G-quadruplex, each of the 44 = 256 possible sequence variants of the central tetrad (corresponding to nucleotides 2, 6, 11, and 15 in the reference construct) were synthesized and tested for the ability to bind GTP using a previously described gel filtration assay (Figure 3A) (17). This revealed an unexpected level of sequence variation compatible with G-quadruplex formation (Figure 3B). The clearest trend could be seen when positions 2 and 6 were guanosines. When this was the case, mutants generally retained significant GTP-binding activity regardless of the nucleotides at positions 11 and 15 (Figure 3B). In addition, several mutants in which positions 2 and/or 6 were not guanosines could also bind GTP efficiently (Figure 3B). After repeating these measurements for the most active mutants identified in the initial screen (Figure 3B), 16 variants with GTP-binding activities >20% of that of the reference construct were obtained (Table 1). Consistent with the idea that GTP-binding activity requires a folded DNA structure, control experiments indicated that these mutants did not bind GTP efficiently when KCl and MgCl2 were omitted from the reaction buffer (Supplementary Figure S2A). These 256 mutants were next tested for peroxidase activity by monitoring oxidation of the colorimetric substrate ABTS (Figure 3C) (19). As was the case in the GTP-binding assay, an unexpected level of sequence variation compatible with G-quadruplex formation was observed (Figure 3D). A second unexpected finding was that the sequence requirements of peroxidase activity were significantly different than those of GTP-binding (Figure 3B and D). This indicates that tetrad sequence plays an important role in determining the biochemical specificity of G-quadruplex activity. The different sequence requirements of these two motifs were most apparent when analyzing mutants in which positions 11 and 15 were guanosines. These mutants generally retained significant peroxidase activity regardless of the nucleotides at positions 2 and 6 even though they did not bind GTP efficiently (Figure 3B and D). After repeating these measurements for the most active mutants, 29 variants with peroxidase activities comparable to that of the reference construct were identified (Table 2). In addition to the reference construct, nine of these variants retained the ability to both bind GTP and oxidize ABTS efficiently (Tables 1 and 2). As was the case for mutants with GTP-binding activity, these variants oxidized ABTS less efficiently when metal ions were omitted from the reaction buffer (Supplementary Figure S2B). These results indicate that, when viewed from the perspective of biochemical activity, G-quadruplexes are more tolerant to mutations than previously thought. They also reveal that G-quadruplexes with different biochemical activities can have distinct sequence requirements.

Figure 3.

Sequence requirements of G-quadruplexes with GTP-binding and peroxidase activity. (A) Measuring the GTP-binding activity of G-quadruplex variants by gel filtration. (B) Heat map showing the GTP-binding activity of all possible variants of the central tetrad in the reference sequence. (C) Measuring the peroxidase activity of G-quadruplex variants using the substrate ABTS. (D) Heat map showing the peroxidase activity of all possible variants of the central tetrad in the reference sequence. All GTP-binding assays were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.1, and 10 nM 32P-γ-GTP. All peroxidase assays were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 8, 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.5 μM hemin, 1% DMSO, 5 mM ABTS, and 600 μM H2O2. Reported values in panels (B) and (D) represent the GTP-binding or peroxidase activity obtained from a single experiment. All measurements >20% of the value of the reference construct in this screen were repeated two more times, and those with an average value > 20% of the reference construct are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1. G-quadruplex variants with GTP-binding activity >20% of the reference construct.

| Tetrad sequence | Relative percent GTP-binding activity |

|---|---|

| GGAG | 900 ± 200 |

| GGAC | 800 ± 500 |

| GGAA | 700 ± 300 |

| GGAT | 450 ± 40 |

| GGTA | 300 ± 100 |

| GGGG | 100 ± 0 |

| GGGA | 100 ± 20 |

| GGCA | 100 ± 40 |

| GGTG | 90 ± 20 |

| GGCG | 70 ± 20 |

| GGTT | 64 ± 7 |

| GGCC | 60 ± 50 |

| GGTC | 50 ± 30 |

| GATT | 30 ± 20 |

| GGGT | 29 ± 8 |

| GGCT | 24 ± 7 |

| TGAG | 20 ± 9 |

Reported values represent the average ± standard deviation of three experiments. Experiments were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.1, and 10 nM 32P-γ-GTP.

Table 2. G-quadruplex variants with peroxidase activity >20% of the reference construct.

| Tetrad sequence | Relative percent peroxidase activity |

|---|---|

| GGGG | 100 ± 0 |

| TGGG | 94 ± 9 |

| ATGG | 88 ± 6 |

| TCGG | 84 ± 16 |

| CCGG | 82 ± 13 |

| CTGG | 80 ± 4 |

| TTGG | 79 ± 8 |

| CGGG | 77 ± 6 |

| AAGG | 77 ± 8 |

| ACGG | 76 ± 7 |

| AGGG | 75 ± 8 |

| CAGG | 73 ± 8 |

| TAGG | 68 ± 4 |

| GTGG | 65 ± 6 |

| GGCC | 62 ± 7 |

| GCGG | 52 ± 1 |

| GGTC | 50 ± 8 |

| GAGG | 45 ± 25 |

| GAAG | 40 ± 4 |

| GCAG | 37 ± 5 |

| GGCG | 35 ± 8 |

| GGTG | 31 ± 8 |

| GGGA | 27 ± 4 |

| GATG | 27 ± 6 |

| GGAG | 27 ± 3 |

| GGGT | 26 ± 7 |

| GGCT | 26 ± 5 |

| GTAG | 25 ± 3 |

| GGGC | 25 ± 7 |

| GGTT | 23 ± 4 |

Reported values represent the average ± standard deviation of three experiments. Experiments were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 8, 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.5 μM hemin, 1% DMSO, 5 mM ABTS, and 600 μM H2O2.

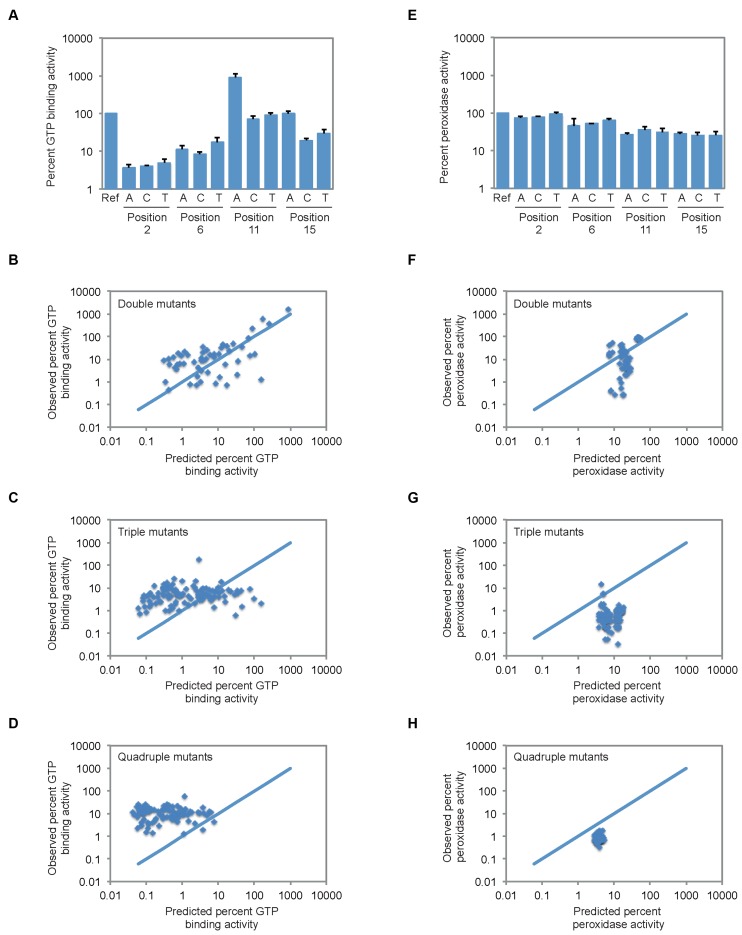

Identification of correlated mutational effects in G-quadruplex structures

To identify correlated mutational effects in this tetrad, we first determined the expected GTP-binding and peroxidase activity of each double, triple, and quadruple mutant using a model in which mutational effects are independent. In this model, the expected effect of a double mutation, for example, is equal to the product of the effects of these two mutations individually. To make these calculations, it was necessary to first determine the effects of point mutations on the ability of the reference construct to bind GTP and to oxidize ABTS. In the case of GTP-binding activity, such changes were not always deleterious (Figure 4A). Furthermore, one of these mutations (11G to 11A) significantly increased the GTP-binding activity of the reference construct (Figure 4A). These results were unexpected because point mutations in G-quadruplex tetrads are typically destabilizing, although several recent studies indicate that such changes are not necessarily incompatible with G-quadruplex formation (49–53). We next analyzed the effects of each of the 54 possible double mutations, 108 possible triple mutations and 81 possible quadruple mutations on the GTP-binding activity of the reference sequence (Figure 4B–D). These experimentally determined values were compared to those expected if the effects of point mutations were independent (indicated by the blue lines in Figure 4B–D). In the case of the double mutants, ∼60% bound GTP within 5-fold of the value expected for independent mutational effects. Moreover, predicted and observed GTP-binding activities were positively correlated (Figure 4B). On the other hand, approximately 30% of mutants bound GTP at least 5-fold more efficiently than predicted, although in many cases the GTP-binding activities of these mutants were low relative to the reference sequence (Figure 4B). In contrast to the double mutants, expected and observed GTP-binding activities were only weakly correlated for triple and quadruple mutants (Figure 4C and D). The activities of most of these mutants were similar, suggesting they had reached a background level of activity. Despite this, several mutants with GTP-binding activities comparable to that of the reference construct were observed among the triple and quadruple mutants. In the case of peroxidase activity, the effects of point mutations were generally smaller than they were on GTP-binding activity (Figure 4E). For this reason, the range of expected activities of double, triple, and quadruple mutants was much narrower than for mutants that bound GTP (Figure 4F–H). Although fewer examples of independent mutational effects were observed, most changes were more deleterious than expected. Despite this, several potential compensatory mutations were identified.

Figure 4.

Correlated mutational effects in G-quadruplexes with GTP-binding and peroxidase activity. (A) GTP-binding activity of all possible single mutant variants of the reference construct. (B–D) GTP-binding activity of all possible double, triple, and quadruple mutant variants of the reference construct. (E) Peroxidase activity of all possible single mutant variants of the reference construct. (F–H) Peroxidase activity of all possible double, triple and quadruple mutant variants of the reference construct. In panels (B–D) and (F–H), the solid blue line indicates the expected relationship for independent mutational effects. All experiments in panels (A–D) were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.1, and 10 nM 32P-γ-GTP. All experiments in panels (E–H) were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 8, 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.5 μM hemin, 1% DMSO, 5 mM ABTS, and 600 μM H2O2. In panels (A) and (E), reported values represent the average of three experiments and error bars indicate one standard deviation. In panels (B–D) and (F-H), reported values represent the GTP-binding or peroxidase activity obtained from a single experiment. In all panels, GTP-binding and peroxidase activity is expressed relative to that of the reference construct.

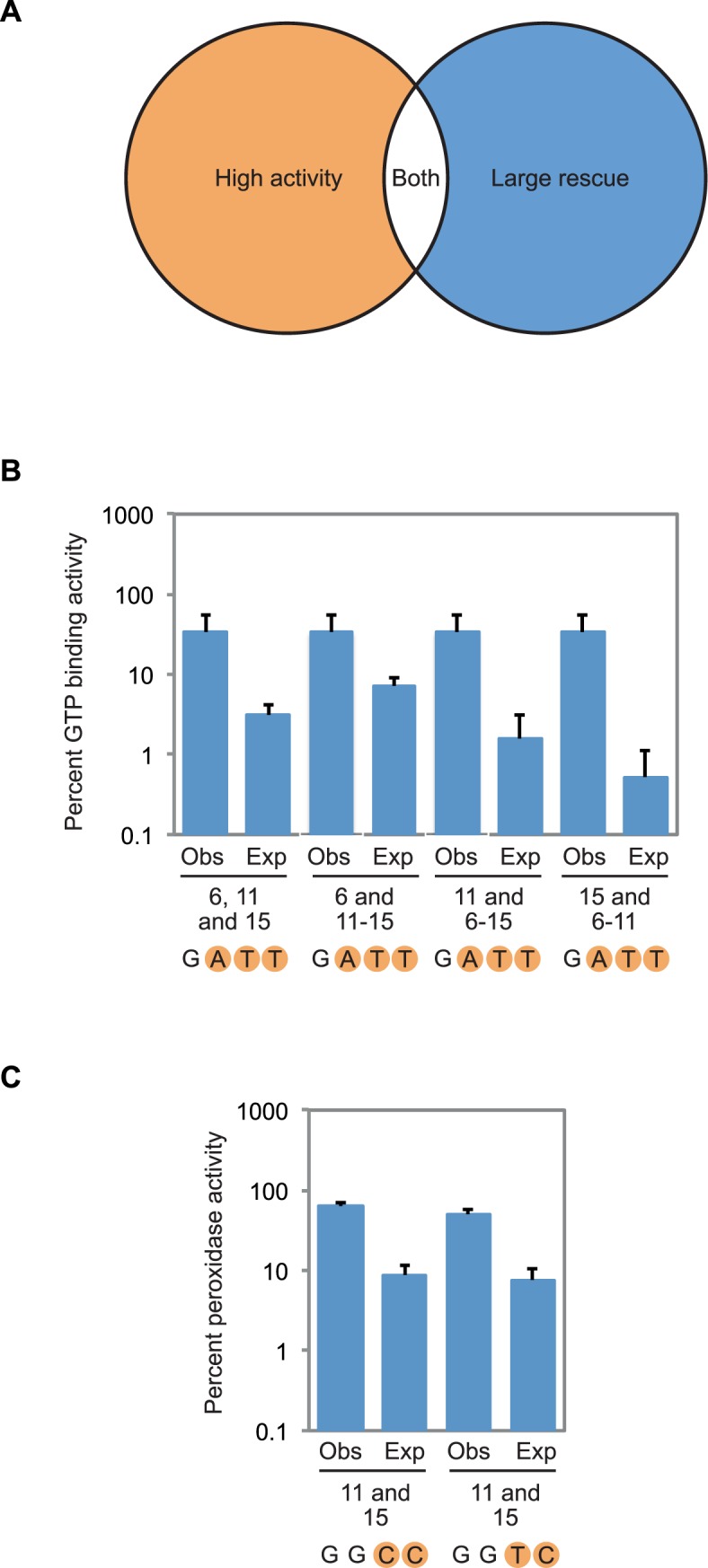

Compensatory mutations in G-quadruplex structures

After identification of potential compensatory mutations, several variants were analyzed in more detail using double and triple mutant cycles. These variants were chosen based on both activity (which was required to be >20% of that of the reference sequence) and extent of rescue (which was required to be at least 5-fold higher than expected based on single mutation effects) (Figure 5A). Among G-quadruplexes that bound GTP, only one variant (containing a G-G-G-G to G-A-T-T mutation) satisfied both of these requirements. The activity of this mutant was 3-fold lower than that of the reference construct, and 11-fold higher than that expected based on multiplying the individual effects of the 6A, 11T, and 15T mutations (Figure 5B). When the expected GTP-binding activity of this triple mutant was calculated using other combinations of single and double mutations (the three possible ways to do this are to multiply the effect of the 6A mutation by that of the 11T-15T mutation, to multiply the effect of the 11T mutation by that of the 6A-15T mutation and to multiply the effect of the 15T mutation by that of the 6A-11T mutation), the fold rescue ranged from 5- to 64-fold, with an average of 25-fold (Figure 5B). Among G-quadruplex variants that promoted peroxidase reactions, two additional compensatory mutants were identified. For each of these mutants, peroxidase activity was 7-fold higher than that expected based on multiplying the effects of single mutations (Figure 5C). Although the extent of rescue seen for the mutants identified in our screen is modest compared to that sometimes observed for base pairs (35, 54), similar effects have been observed for other non-canonical structures such as the CA motif (55). These results establish that compensatory mutations can occur in the context of G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions. This could indicate that, as is the case for canonical G-G-G-G tetrads, these variants can establish a hydrogen bond network, but high-resolution structure determined using a method such as X-ray crystallography or NMR will be needed to confirm this hypothesis. They also indicate that different mutations have compensatory effects in each of these two contexts.

Figure 5.

Compensatory mutations in G-quadruplex structures. (A) Overview of the strategy used to identify compensatory mutations. Variants containing such mutations were chosen based on both activity (which was required to be >20% of that of the reference construct) and extent of rescue (which was required to be at least 5-fold higher than expected based on multiplying single mutation effects). (B) Expected and observed GTP-binding activity for the G-G-G-G to G-A-T-T compensatory change. In each case, expected GTP-binding activity was calculated by multiplying the effects of the mutations that make up the G-G-G-G to G-A-T-T mutant, which are indicated below each pair of measurements. Observed activity is the experimentally measured GTP-binding activity of the indicated mutant. (C) Expected and observed peroxidase activity for the G-G-G-G to G-G-C-C and G-G-G-G to G-G-T-C compensatory changes. In each case, expected peroxidase activity was calculated by multiplying the effects of the individual mutations that make up the G-G-G-G to G-G-C-C or G-G-G-G to G-G-T-C mutant, which are indicated below each pair of measurements. Observed activity is the experimentally measured peroxidase activity of the indicated mutant. Experiments in panel (B) were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.1, and 10 nM 32P-γ-GTP. Experiments in panel (C) were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 8, 0.05% Triton X-100, 0.5 μM hemin, 1% DMSO, 5 mM ABTS, and 600 μM H2O2. In all panels, GTP-binding and peroxidase activity is expressed relative to that of the reference construct. Reported values represent the average of three experiments and error bars indicate one standard deviation. For expected GTP-binding and peroxidase activity, standard deviations were calculated using standard methods of propagation of error.

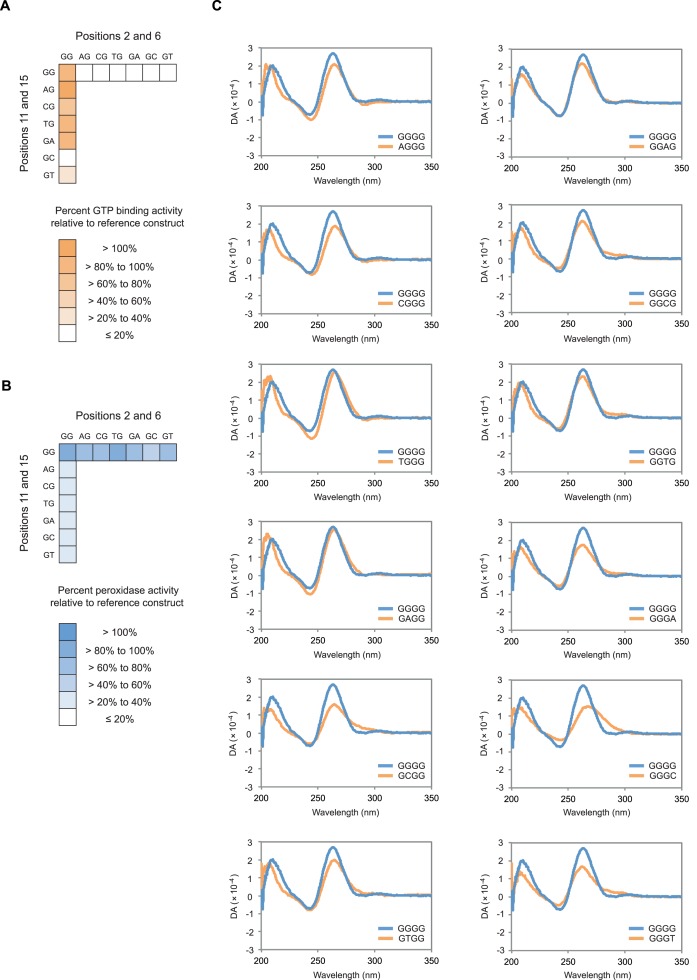

Structural characterization of mutants by circular dichroism spectroscopy and native PAGE

To independently test the ability of these mutants to form G-quadruplex structures, selected variants were characterized by circular dichroism spectroscopy. G-quadruplexes exhibit characteristic circular dichroism spectra (41–42), and previous results indicate that G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions have spectra similar to those of parallel strand structures (17, 45–48). Initial experiments focused on single mutation variants of the reference construct, because the ability of these sequences to bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions are often different (Figure 6A and B). These experiments suggest that each of the 12 single mutant variants of the reference construct we analyzed retain the ability to form parallel strand G-quadruplexes, although in some cases the ability to do so is compromised (Figure 6C). We also analyzed variants with the highest GTP-binding and peroxidase activities (Supplementary Figure S3). This revealed that the most active examples of both types of motifs have spectra consistent with parallel strand G-quadruplex structures, even though some of these sequences contain mutations in two different positions in the central tetrad (Supplementary Figure S3). Because the buffers used for GTP-binding and peroxidase assays are slightly different, we also compared circular dichroism spectra measured in these two conditions. For each variant characterized in this way, spectra were similar or virtually indistinguishable, suggesting that the distinct sequence requirements of G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions are not due to minor differences in the assay conditions (Supplementary Figure S4). Control experiments also indicate that the hemin cofactor used in the peroxidase reactions does not change the circular dichroism spectrum of these G-quadruplexes at the concentrations used in the assay (Supplementary Figure S5). Taken together, these results provide additional support for the idea that the sequence requirements of G-quadruplexes should be expanded to include variants with mutated tetrads. We also investigated whether, like the reference construct, these variants form monomeric structures. To do this, each mutant with GTP-binding or peroxidase activity above our cutoff for significance was analyzed by native PAGE. The position of each construct in the gel was compared to two markers: a random sequence pool of the same length as these G-quadruplexes, and a duplex formed from two complementary strands of the same length as these G-quadruplexes. Approximately 30% of these mutants only formed monomers, and in about 70% of cases the monomer was the main structure (Supplementary Figures S6 and 7). Evidence for at least two other types of structures was also observed (Supplementary Figures S6 and 7). The mobility of one of these structures was similar to that of the duplex marker, and the mobility of the other was significantly reduced relative to single-stranded and double-stranded markers (Supplementary Figures S6 and 7). Establishing the relationship between these structures and those responsible for biochemical function is not straightforward. This is partially because conditions during native PAGE are considerably different from those during assays for GTP-binding and peroxidase activity. In addition, because DNA concentrations during our assays (10 μM) are significantly higher than those of both GTP (10 nM) and hemin (500 nM), it is possible that the predominant structure in solution is different from the biochemically active one. Despite these caveats, these results are consistent with the idea that many of these mutants are active as monomers. At the same time, they raise the possibility that in some cases biochemical function could be mediated by higher-order structures.

Figure 6.

The circular dichroism spectra of single mutant variants of the reference construct are similar to those of parallel strand G-quadruplexes. (A) GTP-binding activity of all single mutant variants of the reference construct. Measurements were performed as described in the legend to Figure 3. (B) Peroxidase activity of all single mutant variants of the reference construct. Measurements were performed as described in the legend to Figure 3. (C) Circular dichroism spectra of all single mutant variants of the reference construct. In each graph, the blue curve represents the circular dichroism spectrum of the reference construct, and the orange curve represents the circular dichroism spectrum of the indicated mutant. DA = differential absorption. All experiments in panel (C) were performed at 10 μM DNA concentration in a buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES pH 7.1 and 10 nM unlabeled GTP.

Sequence models for G-quadruplexes with specific biochemical functions

After identifying mutations that do not disrupt function when present in the central tetrad of G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions, we used this information to develop sequence models for each of these motifs. To do this, we first determined whether mutational effects were similar in 5’, central and 3’ tetrads. In the case of G-quadruplexes that bind GTP, 5 of these 16 mutations could be transplanted to the 5′ tetrad and 9 of these mutations could be transplanted to the 3′ tetrad without significantly impairing function (Figure 7A). We next investigated whether motifs could contain multiple mutated tetrads. In the case of G-quadruplexes that bind GTP, this was not always the case (Supplementary Figure S8), so such sequences were excluded from our model. A final consideration was the sequence requirements of spacer nucleotides. Although previous studies suggest that such spacer sequences have few constraints (21–22), in our model we allowed spacers to be A, C or T but not G. This was necessary so that guanosines in the 5′, central and 3′ tetrads could be unambiguously identified. Of the 7533 possible sequences that satisfy the requirements of our final model (Figure 7B), 10 randomly chosen examples were tested for the ability to bind GTP. The activity of each of these sequences was >20% of that of the reference construct (Figure 7C), and for 9 out of 10 examples this value was within 5-fold of that predicted using a model in which spacer sequence has no effect on GTP-binding activity (Figure 7C). Similar analysis indicated that, in the case of G-quadruplexes that promote peroxidase reactions, mutations that could occur in the central tetrad were also usually tolerated in flanking tetrads (Figure 7D). As was the case for G-quadruplexes that bind GTP, variants that contained multiple mutated tetrads were in some cases not active and such sequences were therefore excluded from our model (Supplementary Figure S9). In addition, although point mutations in spacers had virtually no effect on the ability of G-quadruplexes to promote peroxidase reactions (Supplementary Figure S10), variants that contained multiple mutations in spacers were not necessarily active (Supplementary Figure S11). For this reason, our final model allowed sequences to contain at most one mutation in the spacer (Figure 7E). Of the 946 possible sequences that satisfy the requirements of this model, 30 were tested for the ability to promote peroxidase reactions. The activities of 27 of these 30 sequences were >20% of that of the reference construct, and the activities of all 30 examples were within 5-fold of that predicted using a model in which single mutations in the spacer sequence have no effect on peroxidase activity (Figure 7F). Taken together, these experiments provide additional evidence that G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions have distinct sequence requirements. In addition, the sequence models generated based on these experiments enable bioinformatic searches for G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions to be performed in a more sensitive and specific way than previously possible.

Identification of evolutionarily conserved G-quadruplexes in the human genome

After developing sequence models for G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions, we performed bioinformatic searches for each of these motifs in the human genome. A total of 10 581 G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and 1809 G-quadruplexes that promote peroxidase reactions were identified in this analysis (Figure 8A). The fraction of these examples that contained canonical (G-G-G-G) tetrads was 8.6% for G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and 4.3% for G-quadruplexes that promote peroxidase reactions. Similar results were obtained when more stringent cutoffs for activity were used. For example, when only sequences with activities >50% of that of the reference construct were considered, 9590 G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and 1111 G-quadruplexes that promote peroxidase reactions were identified in the human genome, and when the cutoff for activity was increased to >75% of that of the reference construct, 7999 G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and 754 G-quadruplexes that promote peroxidase reactions were obtained. Approximately 20% of these motifs were conserved in Hominoidea, and 0.25% were conserved in primates (Figure 8A). Although these conserved examples are intriguing, we cannot make a strong statement about their biological relevance because randomly scrambled versions of these motifs were conserved at about the same frequency. A different way to evaluate the significance of conservation is to consider the number of mutations in the alignment of each conserved motif consistent with GTP binding or peroxidase activity. Because in most cases arbitrary mutations are unlikely to be consistent with these sequence requirements, alignments of conserved G-quadruplexes with a higher number of mutations are less likely to occur by chance than those with fewer mutations. This is especially true for cases in which mutations occur in tetrads: based on our data, the probability of such a mutation being compatible with function is 16/255 = 0.06 for G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and 29/255 = 0.11 for G-quadruplexes that promote peroxidase reactions. Of the 3107 conserved G-quadruplexes we identified in Hominoidea that bind GTP, 12% contained mutations in tetrads consistent with the sequence requirements of GTP-binding. Similarly, of the 684 conserved examples we identified in Hominoidea that promote peroxidase reactions, 6% contained mutations in tetrads consistent with the sequence requirements of peroxidase activity (Figure 8B and C). We suggest that these examples represent the strongest candidates for biologically relevant G-quadruplexes that bind GTP or promote peroxidase reactions.

DISCUSSION

In this study we characterized the sequence requirements of G-quadruplexes that bind GTP (17) and promote peroxidase reactions (19), and used this information to analyze the evolutionary conservation of these motifs in the human genome. One of our major conclusions is that, when viewed from the perspective of biochemical activity, G-quadruplexes are surprisingly tolerant to the effects of mutations in tetrads. Previous studies have shown that both point mutations and bulges in tetrads are destabilizing to G-quadruplex structures based on parameters such as melting temperature and ΔG (49–53). For this reason, current sequence models of G-quadruplexes require nucleotides in tetrads to be guanosines (21–22). On the other hand, these studies also indicate that sequences containing mutated tetrads can still typically form G-quadruplexes to some extent. In some cases, such non-canonical tetrads have also been observed in high-resolution structures. For example, A-A-A-A, C-C-C-C, T-T-T-T, A-T-A-T, G-C-G-C and U-U-U-U tetrads have all been reported to occur in G-quadruplexes (56–62). Our study investigated mutational effects in tetrads from a different perspective by focusing on biochemical activity rather than thermal stability. When analyzed in this way, the results show that G-quadruplexes are more tolerant to mutational effects than is currently thought. Since the biochemical activity of G-quadruplexes is the phenotype most likely to be preserved by natural selection, we suggest that using sequence models that incorporate these expanded sequence requirements will significantly improve detection of these structures in sequenced genomes.

Although G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and promote peroxidase reactions are both thought to form parallel strand structures, our results indicate that the sequence requirements of these two motifs are significantly different. This shows that G-quadruplexes with different biochemical activities can have distinct bioinformatic signatures, and enables the classification of G-quadruplexes in a more specific way than was previously possible. These results also indicate that tetrad sequence plays an important role in determining the biochemical specificity of G-quadruplex activity. For example, in the case of the tetrad we analyzed, the GGGG to GGAA mutation increases GTP-binding activity approximately 10-fold while decreasing peroxidase activity by more than 100-fold. On the other hand, the orthogonal GGGG to AAGG change reduces GTP-binding activity by more than 100-fold but has little effect on peroxidase activity. This means that replacing the GGAA tetrad with an AAGG tetrad in the context of the reference construct changes the ratio of GTP-binding activity to peroxidase activity by more than 105-fold.

A second goal of this study was to determine the extent to which compensatory mutations could occur in G-quadruplexes. In the context of DNA and RNA duplexes, A-T (or A-U), T-A (or U-A), C-G and G-C base pairs are often interchangeable, whereas other combinations of nucleotides are not (37). This gives rise to patterns in sequence alignments in which certain double mutations (such as A-T to C-G) occur more frequently than expected based on the frequencies of the corresponding single mutations (A-T to C T or A G). Such covariations are a way to identify base pairs in conserved secondary structures (31–35). Identification of similar patterns in G-quadruplexes would greatly facilitate the detection of biologically relevant examples in sequenced genomes. Although the effects of many of the mutations consistent with G-quadruplex formation we identified were approximately independent when combined, several examples of compensatory mutations were observed. The GTP-binding activity of one of these variants, involving a G-G-G-G to G-A-T-T change, was 11-fold higher than expected based on single mutation effects and up to 64-fold higher than expected based on both single and double mutant effects.

Only a few studies have investigated the evolutionary conservation of G-quadruplexes, and none have used sequence models that allow non-canonical tetrads (63–65). Analysis of the human genome using these improved sequence models revealed that, in some cases, G-quadruplexes with GTP-binding and peroxidase activity have been conserved in evolution. For example, at least 3107 examples of G-quadruplexes that bind GTP and 684 examples that promote peroxidase reactions are conserved in Hominoidea. We propose that these examples represent the G-quadruplexes with GTP-binding and peroxidase activity most likely to play biological roles. A future goal will be to elucidate these potential biological roles in greater detail.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ullrich Jahn, Filip Teplý, Mirek Hájek and colleagues at the IOCB for useful discussions.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry ASCR start-up grant (to E.A.C.). Funding for open access charge: Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry ASCR.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gellert M., Lipsett M.N., Davies D.R. Helix formation by guanylic acid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1962;47:2013–2018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davis J.T. G-quartets 40 years later: from 5′-GMP to molecular biology and supramolecular chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2004;43:668–698. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendrick S., Hurley L.H. The role of G-quadruplex/i-motif secondary structures as cis-acting regulatory elements. Pure Appl. Chem. 2010;82:1609–1621. doi: 10.1351/PAC-CON-09-09-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bugaut A., Balasubramanian S. 5’-UTR RNA G-quadruplexes: translation regulation and targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4727–4741. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes D., Lipps H.J. G-quadruplexes and their regulatory roles in biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:8627–8637. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siddiqui-Jain A., Grand C.L., Bearss D.J., Hurley L.H. Direct evidence for a G-quadruplex in a promoter region and its targeting with a small molecule to repress c-MYC transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:11593–11598. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182256799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huppert J.L., Balasubramanian S. G-quadruplexes in promoters throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:406–413. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kostadinov R., Malhotra N., Viotti M., Shine R., D'Antonio L., Bagga P. GRSDB: a database of quadruplex forming G-rich sequences in alternatively processed mammalian pre-mRNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D119–D124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumari S., Bugaut A., Balasubramanian S. Position and stability are determining factors for translation repression by an RNA G-quadruplex-forming sequence within the 5′ UTR of the NRAS proto-oncogene. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12664–12669. doi: 10.1021/bi8010797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halder K., Wieland M., Hartig J.S. Predictable supression of gene expression by 5′-UTR-based RNA quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:6811–6817. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morris M.J., Negishi Y., Pazsint C., Schonhoft J.D., Basu S. An RNA G-quadruplex is essential for cap-independent translation initiation in human VEGF IRES. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:17831–17839. doi: 10.1021/ja106287x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subramanian M., Rage F., Tabet R., Flatter E., Mandel J.L., Moine H. G-quadruplex RNA structure as a signal for neurite mRNA targeting. EMBO Rep. 2011;2:697–704. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fry M. Tetraplex DNA and its interacting proteins. Front. Biosci. 2007;12:4336–4351. doi: 10.2741/2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brázda V., Hároníková L., Liao J.C., Fojta M. DNA and RNA quadruplex-binding proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014;15:17493–17517. doi: 10.3390/ijms151017493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauhon C.T., Szostak J.W. RNA aptamers that bind flavin and nicotinamide redox cofactors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:1246–1257. doi: 10.1021/ja00109a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y., Geyer C.R., Sen D. Recognition of anionic porphyrins by DNA aptamers. Biochemistry. 1996;35:6911–6922. doi: 10.1021/bi960038h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis E.A., Liu D.R. Discovery of widespread GTP-binding motifs in genomic RNA and DNA. Chem. Biol. 2013;20:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merkle T., Sinn M., Hartig J.S. Interactions between flavins and quadruplex nucleic acids. Chembiochem. 2015;16:2437–2440. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Travascio P., Li Y., Sen D. DNA-enhanced peroxidase activity of a DNA-aptamer-hemin complex. Chem. Biol. 1998;5:505–517. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sen D., Poon L.C. RNA and DNA complexes with hemin [Fe(III) heme] are efficient peroxidases and peroxygenases: how do they do it and what does it mean? Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011;46:478–492. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2011.618220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Todd A.K., Johnston M., Neidle S. Highly prevalent putative quadruplex sequence motifs in human DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2901–2907. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huppert J.L., Balasubramanian S. Prevalence of quadruplexes in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2908–2916. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown B.A., 2nd, Li Y., Brown J.C., Hardin C.C., Roberts J.F., Pelsue S.C., Shultz L.D. Isolation and characterization of a monoclonal anti-quadruplex DNA antibody from autoimmune “viable motheaten” mice. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16325–16337. doi: 10.1021/bi981354u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernando H., Rodriguez R., Balasubramanian S. Selective recognition of a DNA G-quadruplex by an engineered antibody. Biochemistry. 2008;47:9365–9371. doi: 10.1021/bi800983u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biffi G., Tannahill D., McCafferty J., Balasubramanian S. Quantitative visualization of DNA G-quadruplex structures in human cells. Nat. Chem. 2013;5:182–186. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam E.Y., Beraldi D., Tannahill D., Balasubramanian S. G-quadruplex structures are stable and detectable in human genomic DNA. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1796. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henderson A., Wu Y., Huang Y.C., Chavez E.A., Platt J., Johnson F.B., Brosh R.M., Jr, Sen D., Lansdorp P.M. Detection of G-quadruplex DNA in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:860–869. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biffi G., Di Antonio M., Tannahill D., Balasubramanian S. Visualization and selective chemical targeting of RNA G-quadruplex structures in the cytoplasm of human cells. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:75–80. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernando H., Sewitz S., Darot J., Tavaré S., Huppert J.L., Balasubramanian S. Genome-wide analysis of a G-quadruplex-specific single-chain antibody that regulates gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:6716–6722. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chambers V.S., Marsico G., Boutell J.M., Di Antonio M., Smith G.P., Balasubramanian S. High-throughput sequencing of DNA G-quadruplex structures in the human genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:877–881. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levitt M. Detailed molecular model for transfer ribonucleic acid. Nature. 1969;224:759–763. doi: 10.1038/224759a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woese C.R., Gutell R., Gupta R., Noller H.F. Detailed analysis of the higher-order structure of 16S-like ribosomal ribonucleic acids. Microbiol. Rev. 1983;47:621–669. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.4.621-669.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gutell R.R., Power A., Hertz G.Z., Putz E.J., Stormo G.D. Identifying constraints on the higher-order structure of RNA: continued development and application of comparative sequence analysis methods. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5785–5795. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.21.5785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gutell R.R., Lee J.C., Cannone J.J. The accuracy of ribosomal RNA comparative structure models. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2002;12:301–310. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00339-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curtis E.A., Bartel D.P. Synthetic shuffling and in vitro selection reveal the rugged adaptive fitness landscape of a kinase ribozyme. RNA. 2013;19:1116–1128. doi: 10.1261/rna.037572.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson J.D., Crick F.H. Molecular structure of nucleic acids: a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid. Nature. 1953;171:737–738. doi: 10.1038/171737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turner D.H. Thermodynamics of base pairing. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1996;6:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(96)80047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barrick J.E., Corbino K.A., Winkler W.C., Nahvi A., Mandal M., Collins J., Lee M., Roth A., Sudarsan N., Jona I., et al. New RNA motifs suggest an expanded scope for riboswitches in bacterial genetic control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:6421–6426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308014101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weinberg Z., Wang J.X., Bogue J., Yang J., Corbino K., Moy R.H., Breaker R.R. Comparative genomics reveals 104 candidate structured RNAs from bacteria, archaea, and their metagenomes. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-3-r31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perreault J., Weinberg Z., Roth A., Popescu O., Chartrand P., Ferbeyre G., Breaker R.R. Identification of hammerhead ribozymes in all domains of life reveals novel structural variations. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011;7:e1002031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kypr J., Kejnovská I., Renčiuk D., Vorlíčková M. Circular dichroism and conformational polymorphism of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1713–1725. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vorlíčková M., Kejnovská I., Sagi J., Renčiuk D., Bednářová K., Motlová J., Kypr J. Circular dichroism and guanine quadruplexes. Methods. 2012;57:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dsouza M., Larsen N., Overbeek R. Searching for patterns in genomic data. Trends Genet. 1997;13:497–498. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith T.F., Waterman M.S. Identification of common molecular subsequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1981;147:195–197. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu L., Li C., Zhu Z., Liu D., Zou Y., Wang C., Fu H., Yang C.J. In vitro selection of highly efficient G-quadruplex-based DNAzymes. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:8383–8390. doi: 10.1021/ac301899h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kong D.M., Cai L.L., Guo J.H., Wu J., Shen H.X. Characterization of the G-quadruplex structure of a catalytic DNA with peroxidase activity. Biopolymers. 2009;91:331–339. doi: 10.1002/bip.21135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cheng X., Liu X., Bing T., Cao Z., Shangguan D. General peroxidase activity of G-quadruplex-hemin complexes and its application in ligand screening. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7817–7823. doi: 10.1021/bi9006786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kong D.M., Yang W., Wu J., Li C.X., Shen H.X. Structure-function study of peroxidase-like G-quadruplex-hemin complexes. Analyst. 2010;135:321–326. doi: 10.1039/b920293e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gros J., Rosu F., Amrane S., De Cian A., Gabelica V., Lacroix L., Mergny J.L. Guanines are a quartet's best friend: impact of base substitutions on the kinetics and stability of tetramolecular quadruplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3064–3075. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tomasko M., Vorlíčková M., Sagi J. Substitution of adenine for guanine in the quadruplex-forming human telomere DNA sequence G(3)(T(2)AG(3))(3) Biochimie. 2009;91:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sagi J., Renciuk D., Tomasko M., Vorlíčková M. Quadruplexes of human telomere DNA analogs designed to contain G:A:G:A, G:G:A:A, and A:A:A:A tetrads. Biopolymers. 2010;93:880–886. doi: 10.1002/bip.21481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mukundan V.T., Phan A.T. Bulges in G-quadruplexes: broadening the definition of G-quadruplex-forming sequences. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:5017–5028. doi: 10.1021/ja310251r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agarwala P., Kumar S., Pandey S., Maiti S. Human telomeric RNA G-quadruplex response to point mutation in the G-quartets. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:4617–4627. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.5b00619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Curtis E.A., Bartel D.P. New catalytic structures from an existing ribozyme. Nat. Struc. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:994–1000. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Curtis E.A., Liu D.R. A naturally occurring, noncanonical GTP aptamer made of simple tandem repeats. RNA Biol. 2014;11:682–692. doi: 10.4161/rna.28798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pan B., Xiong Y., Shi K., Deng J., Sundaralingam M. Crystal structure of an RNA purine-rich tetraplex containing adenine tetrads: implications for specific binding in RNA tetraplexes. Structure. 2003;11:815–823. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00107-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Virgilio A., Esposito V., Citarella G., Mayol L., Galeone A. Structural investigations on the anti-HIV G-quadruplex-forming oligonucleotide TGGGAG and its analogues: evidence for the presence of an A-tetrad. Chembiochem. 2012;13:2219–2224. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cheong C., Moore P.B. Solution structure of an unusually stable RNA tetraplex containing G- and U-quartet structures. Biochemistry. 1992;31:8406–8414. doi: 10.1021/bi00151a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kimura T., Xu Y., Komiyama M. Human telomeric RNA r(UAGGGU) sequence forms parallel tetraplex structure with U-quartet. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. (Oxf.) 2009;53:239–240. doi: 10.1093/nass/nrp120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Patel P.K., Bhavesh N.S., Hosur R.V. NMR observation of a novel C-tetrad in the structure of the SV40 repeat sequence GGGCGG. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;270:967–971. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patel P.K., Hosur R.V. NMR observation of T-tetrads in a parallel stranded DNA quadruplex formed by Saccharomyces cerevisiae telomere repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2457–2464. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.12.2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang N., Gorin A., Majumdar A., Kettani A., Chernichenko N., Skripkin E., Patel D.J. Dimeric DNA quadruplex containing major groove-aligned A-T-A-T and G-C-G-C tetrads stabilized by inter-subunit Watson-Crick A-T and G-C pairs. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;312:1073–1088. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yadav V.K., Abraham J.K., Mani P., Kulshrestha R., Chowdhury S. QuadBase: genome-wide database of G4 DNA - occurrence and conversation in human, chimpanzee, mouse and rat promoters and 146 microbes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D381–D385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Capra J.A., Paeschke K., Singh M., Zakian V.A. G-quadruplex DNA sequences are evolutionarily conserved and associated with distinct genomic features in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2010;6:e1000861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frees S., Menendez C., Crum M., Bagga P.S. QGRS-Conserve: a computational method for discovering evolutionarily conserved G-quadruplex motifs. Hum. Genomics. 2014;8:8. doi: 10.1186/1479-7364-8-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.