Abstract

Climate change will likely reshuffle ecological communities, causing novel species interactions that could profoundly influence how populations and communities respond to changing conditions. Nonetheless, predicting impacts of novel interactions is challenging, partly because many methods of inference are contingent on today’s configuration of climatic variables and species’ distributions. Focusing on competition, we argue that experiments designed to quantify novel interactions in ways that can inform species distribution models are urgently needed, and suggest an empirical agenda to pursue this goal, illustrated using plants. An emerging convergence of ideas from macroecology and demographically focussed competition theory offers opportunities to mechanistically incorporate competition into species distribution models, whilst forging closer ties between experimental ecology and macroecology.

Keywords: climate change, competition, demography, range dynamics, species distribution model

Biotic interactions and climate change: merging perspectives

Climate change reshuffles ecological communities, altering interactions among species that have co-occurred for centuries [1–8] and generating interactions between species whose ranges previously did not overlap [1–11]. These novel interactions (see Glossary) emerge when species come into contact due to the differential rates at which they expand or contract their ranges with changing climate [2,12,13]. The need to include changing biotic interactions into predictions of species’ range dynamics is widely appreciated [1,2,5,6,14,15], yet how best to do so when some of these interactions do not currently occur remains unclear. Here, we argue that integrating approaches from macroecology, experimental ecology and competition theory could be necessary for the successful incorporation of novel competitive interactions into predictions of species’ range dynamics [16].

When predicting how biotic interactions shape species’ distributions, macroecologists often infer interactions using correlations from large-scale observational data [1,6]. However, correlational species distribution models are not able to extrapolate distributions outside of the ecological conditions (e.g. climate, biotic interactions) within which they were fitted [17]. Therefore, more closely integrating experiments with species distribution modeling could be crucial to directly quantify and predict the impact of novel species interactions on range dynamics. This synthesis of approaches is facilitated by the common demographic basis of interaction outcomes and range dynamics. A species must achieve a positive growth rate when rare if it is to persist within the community at a given location [18], and the places where this criterion is fulfilled define the species’ potential geographic range [5,19,20]. Recent advances in demographic approaches to range modelling [5,21–23] open the door for experiments, guided by ecological theory, to parameterize predictive models of how species interactions, and novel interactions in particular, influence range dynamics.

Integrating experiments into models of species’ distributions, which we argue is often necessary for incorporating the effects of novel interactions, presents formidable empirical and technical challenges [21,24]. Moreover, as we outline below, there are situations in which this integration might not be necessary for the immediate challenge of prediction. Our first goal here is therefore to identify when experimental rather than purely observational approaches will be most important to inform predictions of range dynamics. We then describe how experiments can be used to test hypotheses about how altered competition, and novel interactions in particular, affect species’ distributions, and identify predictors of competitive outcomes. Finally, we explain how information on the changing competitive environment could be used to facilitate more predictive range modelling. Although focusing on competition among plants, we also suggest how the concepts we describe could be applied to other taxa and ecological interactions.

Altered competitive environments after climate change

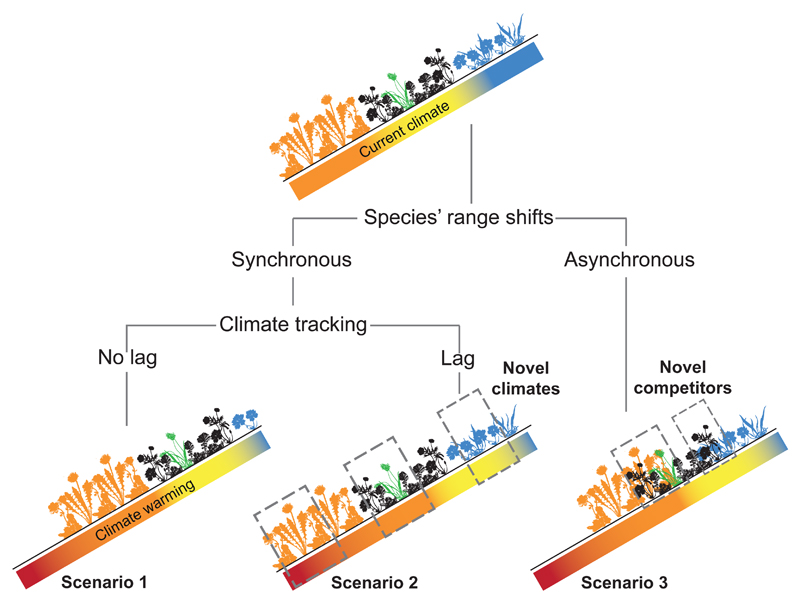

When competitive environments change with climate, they can do so in two distinct ways: (1) through a change in the intensity of interactions among species that already co-occur (including overall reductions in the number of interacting species), and (2) through a change in the identity of interacting species (including overall reductions or gains in the number of interacting species). These processes underlie three bounding scenarios for competition under climate change (Fig. 1, described below).

Figure 1. Scenarios for altered competitive environments after climate change.

The way in which competitive environments are altered following climate change will depend on whether species’ range shifts are synchronous, and how much they lag behind the pace of climate change, giving rise to three scenarios. Each colour represents a different community, consisting of multiple species, and a focal species (green) is highlighted to distinguish these scenarios. Scenario 1, in which all species migrate to track their suitable climates, results in no change in competitive environment. Under scenario 2, all species exhibit the same migration lag, causing them to compete against their same competitors but under altered climate conditions. In some parts of a species’ range (grey boxes), it will face its current competitors under climates different from those previously experienced by these pairs of competitors (e.g. at the trailing range edge; “novel climates”). Under scenario 3, asynchronous migrations alter competitive environments by additionally leading to new combinations of species (“novel competitors”).

Scenario 1. No change in competitive environment

If all species migrate in synchrony, and there is no migration lag relative to climate change, species will experience no change in their climatic or competitive environments. This simplistic scenario is unlikely due to abundant evidence that species’ ranges are shifting at different rates [25], and are lagging behind the rate of climate change [26]. Nonetheless, it is instructive to identify the conditions under which climate change has no effect on competition.

Scenario 2. Altered interactions among current competitors

Currently co-occurring species will compete under an altered climate if they fail to migrate (i.e. in “closed” communities; [2,13]), or if species’ range shifts are synchronous but lag behind the rate of climate change (Fig. 1). A number of studies have already shown that differences among community members in how they respond to changing climate can alter the intensity of competition between them [4,27–30]. For example, observational studies show that plant species within a community vary considerably in their phenological responses to climate change [31], with implications for competitive dynamics [32]. Similarly, experimental manipulations of climate have shown that differential responses to warming changes the abundance of competing Drosophila species [28], and causes subordinate fish competitors to shift habitat [27]. Indeed, such experiments have shown that species’ direct responses to climate manipulations can be modified or even reversed by responses of their competitors [4].

Scenario 3. Altered interactions due to novel competitors

When species shift their ranges at different rates [25], novel interactions will occur among range-expanding and resident species whose distributions do not currently overlap. This reshuffling of ecological communities has been documented in the past [8], and is expected in the future [10], but little is known about the impact of these novel species interactions on climate change responses [2,13]. However, theory [11], experiments [12], and evidence from biological invasions [33] and prehistoric biotic exchanges [8] demonstrate that novel species interactions could have far more significant impacts on community dynamics than changing interactions among currently co-occurring species. How these novel interactions can be incorporated into predictions of species’ range dynamics is the focus of the remainder of this paper.

Accounting for altered competition using correlative approaches

Up to now, effects of species interactions have mainly been incorporated into predictive models of species’ range dynamics using correlative approaches (see review by [1]). Whilst offering limited mechanistic understanding of species’ ranges, these methods are nonetheless well established and readily applicable to a wide range of taxa, and might be useful in some cases where novel interactions emerge with climate change. Therefore, it is important to first identify when correlative approaches will successfully predict impacts of altered competitive environments even in the face of novel interactions.

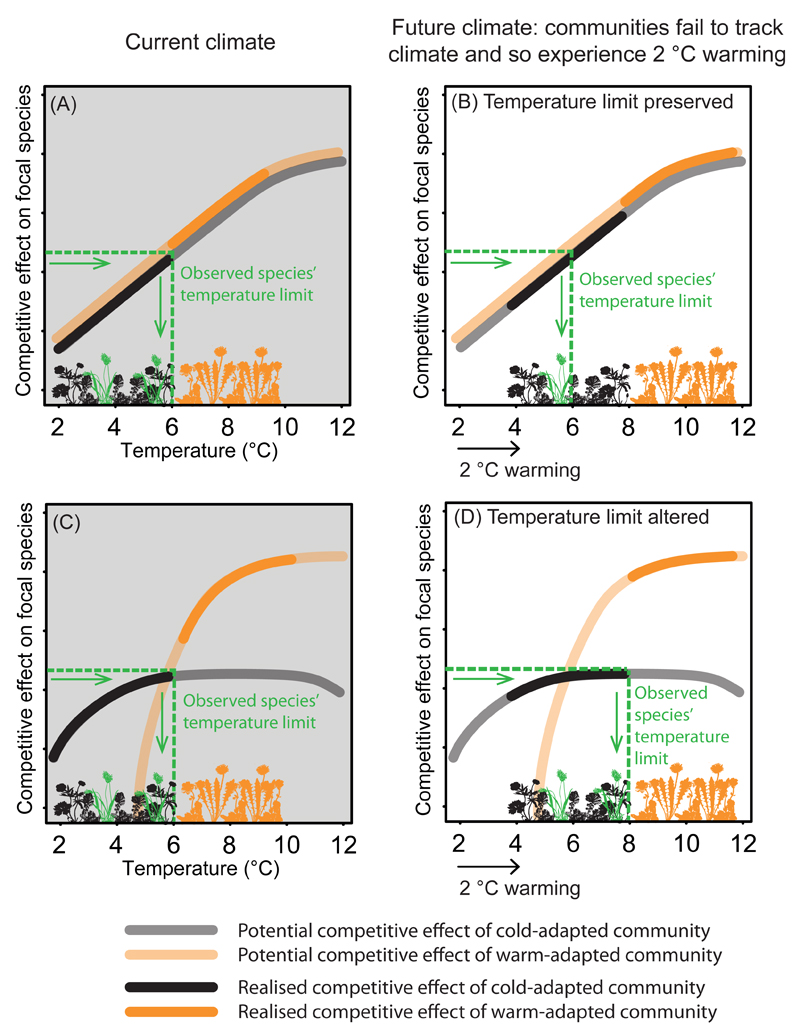

As reviewed elsewhere [34], species distribution models (SDMs) use the environmental conditions where species currently occur to predict new distributions either in space or time. Species interactions are implicitly included in SDMs because the abundance or occurrence observations used to build SDMs inherently reflect the outcomes of interactions (i.e. correlative SDMs model species’ realized niches). Thus, predictions of range dynamics based solely on climatic variables make the assumption that changing interactions do not disrupt the current association between climate and competitive effects (Fig. 2A,B). Though unlikely to be generally true, this assumption will hold in cases where competitor identity shifts with climate, but competitive effects do not (e.g. a shift from the orange to black set of competitors in Fig. 2B does not alter the competition experienced by the green focal species). Climate-dependent competitor size, for example, can mediate the strength of suppression experienced by a focal species independently of competitor identity [35]. Indeed, observations and experiments in tundra ecosystems reveal increasing plant height and productivity following climate warming, associated with declines in abundance of some lower-stature taxa [36].

Figure 2. Associations between effects of competition and temperature after climate change.

The figure depicts the case of a focal species (green) with a distribution limited by the competitive effect of its surrounding community (horizontal dashed line). Competitive effects are correlated with the temperature where the competitors are found, resulting in a realised temperature limit for the focal species of 6 °C under current climate (vertical dashed line). In (A), the two communities (black, cold-adapted and orange, warm-adapted) exert the same competitive effect on the focal species under an identical temperature. (B) After climate change, existing populations experience a 2 °C climate warming (cf. scenario 2 in Fig. 1), inducing an increase in competitive effects such that the focal species is competitively excluded from any site warmer than 6 °C by the cold-adapted community. In this scenario, an SDM would accurately predict effects of competition on the focal species’ distribution using the temperature variable alone. (C) Alternatively, the cold- and warm-adapted communities might differ in their competitive effects under identical temperatures, with the cold-adapted community exerting stronger competition under cool temperatures and the warm-adapted community exerting stronger competition under warm temperatures. (D) As a result, the focal species can persist in sites up to 8 °C following climate warming. Predicting this alteration of the species’ realised temperature limit would require explicitly accounting for competitor identity.

Although current correlative approaches have begun including competitor distributions as covariates in SDMs [e.g. 37], or jointly modelling the distribution of multiple species [38,39], novel interactions present challenges that purely observational approaches are unlikely to resolve. The problem is that competitive effects inferred from observed occurrences are contingent on the current configuration of climate variables and competing species. Correlative techniques cannot therefore be used to infer effects of entirely novel competitors (Fig. 1, scenario 3; Fig. 2D) or the interaction between current competitors under climate conditions in which they do not occur today. The outcome of interactions among novel competitors, or any set of competitors under novel climates, must be determined experimentally. Therefore, accurate prediction of range dynamics could depend on combining experiments and theory to build a mechanistic understanding of how competition affects distributions.

An experimental agenda for predicting effects of altered competition

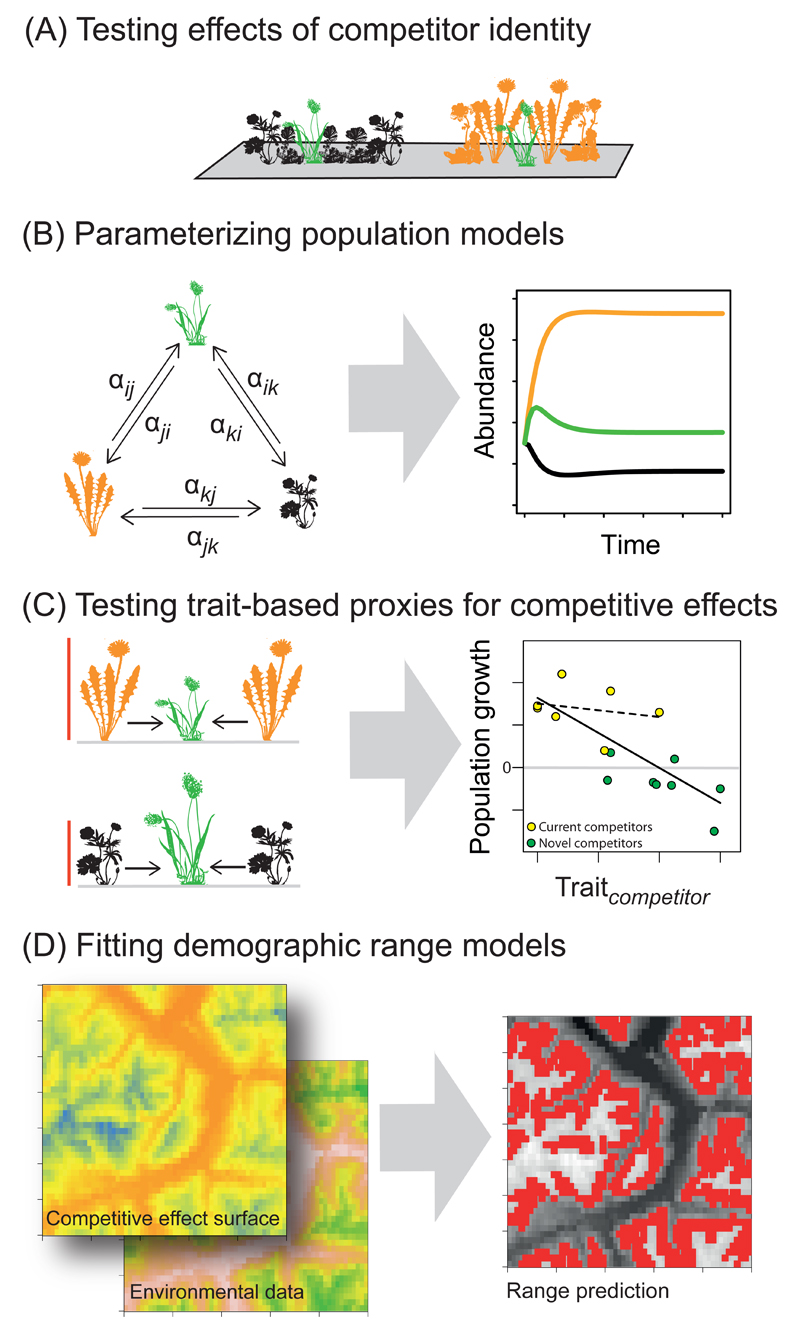

Given the inherent limitations of correlative approaches, we outline steps towards mechanistically including competition, and novel competitors in particular, into predictions of species’ range dynamics (Fig. 3). Here we focus explicitly on plant competition, which has so far received most theoretical and empirical attention, but also suggest how these ideas could be expanded to other taxa and trophic interactions in Box 1. Whilst the whole sequence of experiments and models might be daunting, each individual step of this research agenda is valuable for addressing an important gap in our understanding of how competition affects species’ ranges.

Figure 3. An empirical agenda for predicting effects of competition on range dynamics.

(A) Growing a focal species with different competitors under a common environment can test whether competitor identity influences the outcome of competition. (B) If competitor identity effects are important, experiments can parameterize population models to predict competitive outcomes among current and potential future competitors under a given environment. (C) Because estimating competition coefficients (α) among all species pairs will often be prohibitive, experiments can also test the power of functional traits (such as height) to predict competitive outcomes. We hypothesise that traits are stronger predictors of competitive outcomes when including novel competitors. (D) Finally, experimental results could inform demographic range models that integrate a focal species’ response to its abiotic and competitive environments (e.g. using traits of competitors to describe a “competitive effect surface”) to predict current and future distributions.

Box 1. Species interactions across taxa and trophic interactions.

The empirical agenda we describe could be extended to other taxa and types of interaction. Sessile communities – including soil biota, lichens, or marine fouling communities – might be transplanted in a similar way to plants [60] to evaluate the competitive consequences of their differential migration. More mobile, small-bodied organisms including bees [61] and butterflies [62] can be transplanted along climate gradients and contained in cages. Manipulations like these could be crossed with plant community transplantations [12] to investigate interactions between differentially migrating plant and animal communities and climate. A similar approach could test how different soil communities affect the outcome of plant competition.

For those taxa not amenable to field transplantation, experimental communities can often be assembled and reared under common climates in controlled environments. Mesocosms such as artificial ponds provide an effective setting to test species interactions in many animal communities, including the temperature-dependence of interactions [63]. For example, laboratory studies have been used to test how fish respond to novel competitors and predators [64]. Clever experimental designs can also be used to explore novel phenological interactions, for example by transplanting pollinator communities [61], or manipulating plant community composition and phenology in potted plants [65]. Experiments like these could be used to parameterize population models in a very similar way as done with competing plants (Fig. 3B).

The use of trait proxies for the outcome of trophic interactions, especially among animals, is generally more developed than for plants [48]. For example, traits such as body size and diet breadth could be useful predictors of responses to climate change and novel interactions [2,13]. Novel plant-insect interactions can be predicted to some degree using phylogenetic relationships [33]. Where trait information is lacking, the empirical approaches we describe, tailored to the organism, can be used to test the ability of traits to predict the outcome of novel interactions (Fig. 3C) (e.g. for fish [64]). Finally, process-based distribution models that include species interactions can be built for animal systems, including trophic interactions (Fig. 3D) [1]. The demographic range-modelling framework provides an opportunity to account for these interactions through their impact on population growth rates.

Testing the effects of novel competitors

The first step when deciding how to account for competition in an SDM should be to establish whether the effects of competition depend on the identity of the competitors, or if they can be sufficiently predicted using climate variables alone (Fig. 2). While it is trivial that individual species differ in their competitive effects, it is less clear how far this extends to whole communities that are functionally similar (e.g. grasslands) yet composed of different taxa [12]. The ideal test would expose focal species to different competitive backgrounds whilst controlling for abiotic conditions along an environmental gradient (Fig. 3A). In particular, the different competitor identities and environmental conditions should correspond to different migration scenarios with climate change, ideally informed by species’ predicted migration rates. For example, in one such experiment the performance of alpine plants was strongly reduced by competitors from lower elevation compared to their current high elevation competitors, when growing under a common warmer climate [12]. Similarly, survival of Mediterranean shrub seedlings differed when growing in herbaceous communities from semi-arid or mesic-Mediterranean sites in a common garden experiment [40]. Both examples suggest that changing competitor identity could strongly influence focal species’ range dynamics, though not necessarily in all parts of the range [12].

Direct experimental tests of competitor community identity effects are scarce, and will only be feasible for relatively short-lived or experimentally tractable taxa. For other taxa, performance of a focal species can be compared across sites with very similar environmental conditions but different competitive environments [1]. For example, different dominant competitors can alter the abundance of focal tree species under otherwise similar environments along macro-climatic gradients [41,42]. However, as described in the previous section, correlative approaches cannot fully exclude the effects of environmental variables correlated with competitor composition [1]. In sum, tests for competitor identity effects are necessary to reveal the qualitative importance of changing competition when predicting species range dynamics. But as we discuss next, quantitatively predicting these dynamics over longer time scales, and for a wide range of taxa, will require complementary approaches.

Local site predictions: parameterizing competition models

In many cases we expect that the identities of the species making up a community must be explicitly accounted for when predicting a focal species’ ability to persist at that location (Fig. 3B). Population models that describe effects of competitors on a focal species’ demographic rates provide the theoretical basis to do so. In these models, a focal species’ persistence in a site depends on its own intrinsic growth rate as well as the abundance and per capita effects (“interaction coefficients”) of its competitors, all of which could vary with environmental conditions [18]. Experiments that estimate these parameters for all potentially co-occurring species (current and future competitors), and conducted under a range of environmental conditions, would provide the most complete picture of competitor effects after climate change. Interaction coefficients can alternatively be obtained from observational data using neighbourhood competition models [43–45], thus reserving experiments for quantifying the effects of competition under novel climates or between novel competitors. This general approach is probably most feasible when predicting competitive outcomes at a single site, with a limited number of potentially interacting species [44,45], although in principle it can be extended to multiple sites across a species’ range. Nonetheless, due to the labour intensive nature of experiments required to parameterize competition models [46], the potential scope of such studies is limited. Therefore, we next explore ways to extend this approach to more complex systems.

Practical approaches to predicting competitive outcomes

A number of simplifications and assumptions could be used to facilitate the design of experiments that inform predictions of range dynamics, especially when considering how to incorporate the effects of novel competitors. First, one can focus on the most abundant or dominant competitors [37], or those known to interact most strongly with a given focal species [2]. Second, one can focus on species with the strongest and weakest dispersal potential, because these are most likely to engage in novel interactions. Third, one might assume that competitor effects do not vary with environmental conditions, allowing model parameterization at only one or two sites. This might be reasonable in some systems, as plant responses to competition have been shown to remain constant across precipitation regimes in some ecosystems [29,30], and per capita effects of invertebrate competitors can be invariant across marine environmental gradients [47].

Nonetheless, the simplifying assumptions of the prior paragraph may prove too unrealistic, especially in cases where climate change forces numerous novel competitive interactions. Thus, progress might depend on developing theoretically robust and efficient proxies for competitive outcomes. The importance of proxies for species interactions has been noted previously [48], but here we specifically identify their role in determining the outcome of novel interactions. Differences between species in plant height [35], biomass [49], leaf economic traits [50,51], wood density [50] and phenology [52] have emerged as strong predictors of competitive hierarchies when plants compete for shared resources. However, the utility of traits for predicting effects of competitors on range dynamics remains unclear for two main reasons. First, experiments rarely quantify competitive effects on population growth rates [e.g. 52], which is the most relevant response variable for linking competition to species distributions. Even a competitively inferior species might persist (i.e. increase when rare) with a superior competitor if the species are sufficiently niche differentiated (sensu [18]).

Second, nearly all current studies have investigated how traits predict interactions among species that co-occur in communities today. Communities are composed of species with shared evolutionary history, and that have survived shared environmental and competitive filtering, both of which can reduce trait variation [48]. In contrast, we would expect novel communities, initially at least, to show expanded trait variation through the mixing of evolutionarily and bioclimatically divergent lineages (Fig. 3C). Therefore we hypothesize that even traits that are poor predictors of competitive outcomes among current competitors [52] might more strongly predict competition among novel competitors and under novel climates.

Experiments can test this hypothesis by growing focal species with a range of different competitors, including both current and potential future competitors, and thereby include a broad range of functional trait variation (Fig. 3C). The effect of competition on demographic rates can then be correlated with the traits of the competitors. Empirical approaches like these will help identify traits that most strongly predict competitive outcomes, and the extent to which their effects can be generalized across species and ecosystems. For example, the traits most relevant to predicting competition might differ across groups of taxa with distinct life-history strategies [53]. In sum, further development of this trait-based approach could provide the necessary basis to predict the communities in which a species can invade or persist.

Integrating competition into models of range dynamics

The final challenge is the incorporation of experimental findings into species’ range predictions (Fig. 3D) [54]. Here, recent advances in demography-based range models offer exciting opportunities to incorporate effects of any interaction, including competition, into predictions of species’ current and future distributions [21–23]. Given that demography plays a central role in determining where species occur [5,20,21,55], dynamic range models (DRMs) [21,22,56] provide flexible solutions to modelling range dynamics. These models can incorporate demographic responses to the environment, spatial population dynamics and associated uncertainties [21]. Because they model demography directly, DRMs allow ecologists to also incorporate the complex effects of different types of interaction, including competition. This could be achieved by embedding competition models into a DRM, parameterized with estimates of competition coefficients or using proxies such as traits of interacting species. The importance of accounting for intraspecific density dependence in such population models has recently been emphasized [19], and including interspecific interactions should be the next step.

Should macroecologists be experimenters?

Given the likely emergence of novel interactions under climate change, we believe that the experimental approaches we have advocated will be crucial to advance understanding of species’ ranges and their dynamics. An important component of this experimental agenda is to test assumptions, often implicit in range models, about how competition shapes species’ distributions [15]. We have argued that whilst climate predictors alone might sometimes be a sufficient proxy for competitive effects, in other cases greater mechanistic understanding will be necessary, particularly with novel climates and competitors. Many other challenges still remain, including determining how novel interactions other than competition could be incorporated into range models (Box 1). Here, close collaboration between experimental ecologists and species distribution modellers could be especially fruitful.

Such collaboration has great potential to resolve other open questions, such as whether the extent to which biotic interactions should be taken into account depends on the spatial grain at which distributions are modelled [57]. A more fundamental future question concerns the role of adaptation in determining the outcome of novel competitive interactions. Some species adapt to novel competitors during biological invasions [58], and competitors can impose evolutionary constraints at species’ range margins [59]. However, whether adaptation to changing competitive environments could substantially influence range dynamics remains an open question. Though the empirical and modelling challenges are daunting, the need to reliably predict impacts of climate change on species’ ranges presents an exciting opportunity to forge closer ties between macroecology and experimental ecology [16], and ultimately lead to a deeper mechanistic understanding of the factors shaping species’ distributions.

Outstanding questions.

When will climate variables predict effects of altered competition following climate change? If effects of competition on a focal species do not depend on the specific identities of its competitors, but can be predicted by climate variables, modelling range dynamics is simplified. Yet how commonly such simplification is possible, and under which ecological settings (e.g. subsets of a species’ range where potential competitors are functionally similar) is unclear.

Do functional traits predict competitive outcomes among novel competitors? Although traits sometimes predict competitive dominance among currently co-occurring species, few empirical studies have tested whether traits are also associated with competitive outcomes between novel competitors. Furthermore, traits predicting competitive effects or responses may vary across groups of species with, for example, different life-histories or growth forms, but this has yet to be established.

How can biotic interactions be best incorporated into demographic models of range dynamics? Demographic range models offer a way to account for effects of biotic interactions on range dynamics through their impact on vital rates, but these models have yet to be extended to incorporate interspecific interactions.

To what extent will evolution influence competitive outcomes following climate change, and will evolutionary change alter predicted range dynamics? Species can adapt to both changing climate, and to changing interactions with their current or novel competitors. The consequences of this evolution for population persistence or range expansion are poorly understood.

At what spatial resolution of a species’ distribution is accounting for effects of biotic interactions most important? Although biotic interactions can potentially shape geographic scale distributions, the importance of accounting for effects of competition – and other biotic interactions – will likely increase when modelling species’ distributions at finer spatial resolutions.

Trends.

Biotic interactions can influence how species respond to changing climate, making it necessary to account for changing interactions when predicting future range dynamics.

Competitor effects on species’ ranges can be inferred with observational techniques, but not when species compete under novel climates, or together with novel competitors.

Experiments can improve predictions of range dynamics by (1) testing assumptions about how competitors shape distributions, (2) estimating interaction strengths among potentially co-occurring species under different climate change scenarios, and (3) testing functional traits as proxies for competitive outcomes.

Through its impact on demographic rates, competition can be incorporated into predictions of species’ distributions by capitalizing on recent advances in demographic range modelling.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Plant Ecology group, Jörn Pagel and Frank Schurr for helpful comments, and Teresa Bohner, Courtney Collins, and Sören Weber for useful discussion of these ideas. ETH Zurich funding to the Plant Ecology group supported this work. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 678841.

Glossary Box

- Competition coefficient (α)

the per capita effect of a competitor species on the population growth rate of a focal species.

- Dynamic range model (DRM)

a statistical model to predict species’ range dynamics based on environment-demography relationships and parameters of spatial population dynamics that are jointly estimated from observational data.

- Functional traits

characteristics of a species (e.g. morphological, physiological, phenological) that determine how the species responds to, and affects, its abiotic and biotic environment.

- Intrinsic rate of increase

the rate of population growth in the absence of density-dependent forces (such as competition).

- Novel climate

climate conditions not previously experienced by a given species anywhere in its current range.

- Novel interaction

an interaction between species whose distributions did not previously overlap, but do overlap following migration with climate change or after introduction to new biogeographic regions.

- Species distribution model (SDM)

a model that predicts a species’ potential geographical distribution based on statistical relationships among observed occurrences or abundances and environmental data.

References

- 1.Wisz MS, et al. The role of biotic interactions in shaping distributions and realised assemblages of species: implications for species distribution modelling. Biol Rev. 2013;88:15–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilman SE, et al. A framework for community interactions under climate change. Trends Ecol Evol. 2010;25:325–331. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tylianakis JM, et al. Global change and species interactions in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol Lett. 2008;11:1351–1363. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suttle KB, et al. Species interactions reverse grassland responses to changing climate. Science. 2007;315:640–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1136401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Svenning J-C, et al. The influence of interspecific interactions on species range expansion rates. Ecography. 2014;37:1198–1209. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.00574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kissling WD, et al. Towards novel approaches to modelling biotic interactions in multispecies assemblages at large spatial extents. J Biogeogr. 2012;39:2163–2178. [Google Scholar]

- 7.HilleRisLambers J, et al. How will biotic interactions influence climate change–induced range shifts? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1297:112–125. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blois JL, et al. Climate change and the past, present, and future of biotic interactions. Science. 2013;341:499–504. doi: 10.1126/science.1237184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kordas RL, et al. Community ecology in a warming world: The influence of temperature on interspecific interactions in marine systems. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 2011;400:218–226. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams JW, Jackson ST. Novel climates, no-analog communities, and ecological surprises. Front Ecol Environ. 2007;5:475–482. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban MC, et al. On a collision course: competition and dispersal differences create no-analogue communities and cause extinctions during climate change. Proc R Soc B. 2012;279:2072–2080. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexander JM, et al. Novel competitors shape species' responses to climate change. Nature. 2015;525:515–518. doi: 10.1038/nature14952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lurgi M, et al. Novel communities from climate change. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2012;367:2913–2922. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulangeat I, et al. Anticipating the spatio-temporal response of plant diversity and vegetation structure to climate and land use change in a protected area. Ecography. 2014;37:1230–1239. doi: 10.1111/ecog.00694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louthan AM, et al. Where and when do species interactions set range limits? Trends Ecol Evol. 2015;30:780–792. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nogués-Bravo D, Rahbek C. Communities Under Climate Change. Science. 2011;334:1070–1071. doi: 10.1126/science.1214833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitzpatrick M, Hargrove W. The projection of species distribution models and the problem of non-analog climate. Biodivers Conserv. 2009;18:2255–2261. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chesson P. Mechanisms of maintenance of species diversity. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2000;31:343–366. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrlén J, Morris WF. Predicting changes in the distribution and abundance of species under environmental change. Ecol Lett. 2015;18:303–314. doi: 10.1111/ele.12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diez JM, et al. Probabilistic and spatially variable niches inferred from demography. J Ecol. 2014;102:544–554. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schurr FM, et al. How to understand species’ niches and range dynamics: a demographic research agenda for biogeography. J Biogeogr. 2012;39:2146–2162. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagel J, Schurr FM. Forecasting species ranges by statistical estimation of ecological niches and spatial population dynamics. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2012;21:293–304. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zurell D, et al. Benchmarking novel approaches for modelling species range dynamics. Glob Chang Biol. 2016;22:2651–2664. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Latimer A, et al. Experimental biogeography: the role of environmental gradients in high geographic diversity in Cape Proteaceae. Oecologia. 2009;160:151–162. doi: 10.1007/s00442-009-1275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parmesan C. Ecological and evolutionary responses to recent climate change. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2006;37:637–669. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lenoir J, Svenning JC. Climate-related range shifts – a global multidimensional synthesis and new research directions. Ecography. 2015;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milazzo M, et al. Climate change exacerbates interspecific interactions in sympatric coastal fishes. J Anim Ecol. 2013;82:468–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2012.02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis AJ, et al. Making mistakes when predicting shifts in species range in response to global warming. Nature. 1998;391:783–786. doi: 10.1038/35842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine JM, et al. Do competitors modulate rare plant response to precipitation change? Ecology. 2010;91:130–140. doi: 10.1890/08-2039.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adler PB, et al. Direct and indirect effects of climate change on a prairie plant community. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diez JM, et al. Forecasting phenology: from species variability to community patterns. Ecol Lett. 2012;15:545–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang LH, Rudolf VHW. Phenology, ontogeny and the effects of climate change on the timing of species interactions. Ecol Lett. 2010;13:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearse IS, Altermatt F. Predicting novel trophic interactions in a non-native world. Ecol Lett. 2013;16:1088–1094. doi: 10.1111/ele.12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guisan A, Thuiller W. Predicting species distribution: offering more than simple habitat models. Ecol Lett. 2005;8:993–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaudet CL, Keddy PA. A comparative approach to predicting competitive ability from plant traits. Nature. 1988;334:242–243. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elmendorf SC, et al. Global assessment of experimental climate warming on tundra vegetation: heterogeneity over space and time. Ecol Lett. 2012;15:164–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.le Roux PC, et al. Incorporating dominant species as proxies for biotic interactions strengthens plant community models. J Ecol. 2014;102:767–775. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollock LJ, et al. Understanding co-occurrence by modelling species simultaneously with a Joint Species Distribution Model (JSDM) Methods Ecol Evol. 2014;5:397–406. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ovaskainen O, et al. Modeling species co-occurrence by multivariate logistic regression generates new hypotheses on fungal interactions. Ecology. 2010;91:2514–2521. doi: 10.1890/10-0173.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rysavy A, et al. Neighbour effects on shrub seedling establishment override climate change impacts in a Mediterranean community. J Veg Sci. 2016;27:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leathwick JR, Austin MP. Competitive interactions between tree species in new zealand's old-growth indigenous forests. Ecology. 2001;82:2560–2573. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meier ES, et al. Co-occurrence patterns of trees along macro-climatic gradients and their potential influence on the present and future distribution of Fagus sylvatica L. J Biogeogr. 2011;38:371–382. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adler PB, et al. Forecasting plant community impacts of climate variability and change: when do competitive interactions matter? J Ecol. 2012;100:478–487. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Adler PB, HilleRisLambers J. The influence of climate and species composition on the population dynamics of ten prairie forbs. Ecology. 2008;89:3049–3060. doi: 10.1890/07-1569.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kunstler G, et al. Competitive interactions between forest trees are driven by species' trait hierarchy, not phylogenetic or functional similarity: implications for forest community assembly. Ecol Lett. 2012;15:831–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Freckleton RP, Watkinson AR. Designs for greenhouse studies of interactions between plants: an analytical perspective. J Ecol. 2000;88:386–391. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hart SP, Marshall DJ. Environmental stress, facilitation, competition, and coexistence. Ecology. 2013;94:2719–2731. doi: 10.1890/12-0804.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morales-Castilla I, et al. Inferring biotic interactions from proxies. Trends Ecol Evol. 2015;30:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freckleton RP, Watkinson AR. Predicting competition coefficients for plant mixtures: reciprocity, transitivity and correlations with life-history traits. Ecol Lett. 2001;4:348–357. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kunstler G, et al. Plant functional traits have globally consistent effects on competition. Nature. 2016;529:204–207. doi: 10.1038/nature16476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kraft NJB, et al. Functional trait differences and the outcome of community assembly: an experimental test with vernal pool annual plants. Oikos. 2014;123:1391–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kraft NJB, et al. Plant functional traits and the multidimensional nature of species coexistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:797–802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413650112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adler PB, et al. Functional traits explain variation in plant life history strategies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:740–745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315179111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maynard DS, et al. Modelling the multidimensional niche by linking functional traits to competitive performance. Proc R Soc B. 2015;282 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dullinger S, et al. Modelling climate change-driven treeline shifts: relative effects of temperature increase, dispersal and invasibility. J Ecol. 2004;92:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Merow C, et al. On using integral projection models to generate demographically driven predictions of species' distributions: development and validation using sparse data. Ecography. 2014;37:1167–1183. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Godsoe W, et al. The effect of competition on species' distributions depends on coexistence, rather than scale alone. Ecography. 2015;38:1071–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lankau RA. Coevolution between invasive and native plants driven by chemical competition and soil biota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11240–11245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201343109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Emery NC, Ackerly DD. Ecological release exposes genetically based niche variation. Ecol Lett. 2014;17:1149–1157. doi: 10.1111/ele.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chang CY, Marshall DJ. Quantifying the role of colonization history and biotic interactions in shaping communities. Oikos. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Forrest JRK, Thomson JD. An examination of synchrony between insect emergence and flowering in Rocky Mountain meadows. Ecol Monogr. 2011;81:469–491. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buckley J, Bridle JR. Loss of adaptive variation during evolutionary responses to climate change. Ecol Lett. 2014;17:1316–1325. doi: 10.1111/ele.12340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stewart RI, et al. Mesocosm experiments as a tool for ecological climate-change research. Adv Ecol Res. 2013;48:71–181. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rehage JS, et al. Behavioral responses to a novel predator and competitor of invasive mosquitofish and their non-invasive relatives (Gambusia sp.) Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 2005;57:256–266. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rafferty NE, Ives AR. Effects of experimental shifts in flowering phenology on plant-pollinator interactions. Ecol Lett. 2011;14:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]