Abstract

Endoscopy is a keystone in the management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It is the fundamental diagnostic tool for IBD, and can help discern between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Endoscopic assessment provides an objective end point in clinical trials, and identifies patients in clinical practice who may benefit from treatment escalation and may assist risk stratification in patients seeking to discontinue therapy. Recent advances in endoscopic assessment of patients with IBD include video capsule endoscopy, and chromoendoscopy. Technological advances enable improved visualization and focused biopsy sampling. Endoscopic resection and close surveillance of dysplastic lesions where feasible is recommended instead of prophylactic colectomy.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, Endoscopy, Capsule endoscopy, Cancer surveillance, Colonoscopy

Core tip: Ileo-colonoscopy remains the most important test in the diagnosis and monitoring of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Video capsule endoscopy shows very high sensitivity for small bowel mucosal lesions not accessible to conventional flexible endoscopes. Both techniques facilitate monitoring of response to treatment. Endoscopic activity indices are important for monitoring treatment response and can help identify patients who may benefit from treatment escalation. Colorectal cancer surveillance in patients with IBD is shifting from high frequency random biopsies, to that of high quality visual inspection and targeted biopsies of suspected dysplasia, enabled by technological advances including chromoendoscopy and high-definition endoscopes.

INTRODUCTION

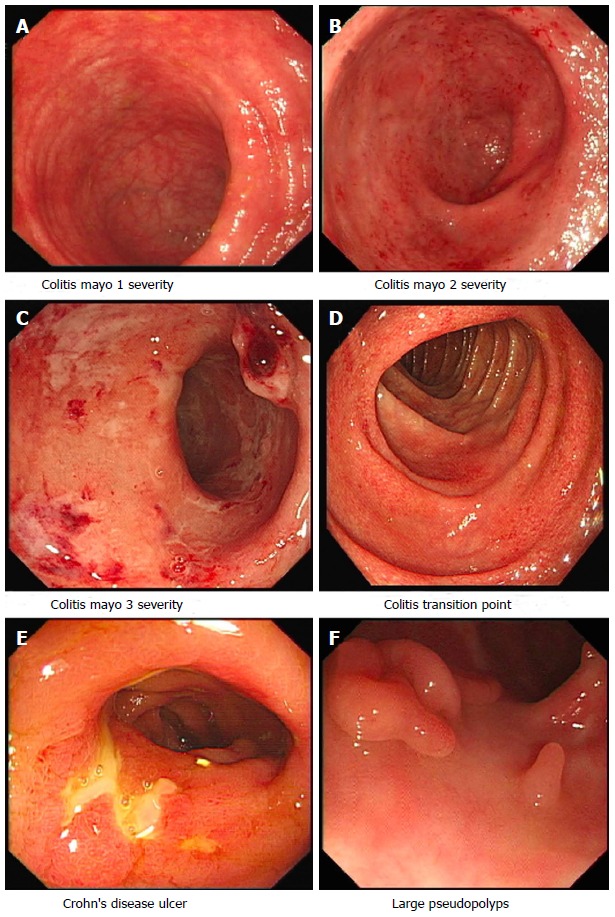

Endoscopy plays an integral role in the diagnosis and management of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In patients with lower gastro-intestinal symptoms suggestive of IBD, colonoscopy with intubation, evaluation and biopsies of the terminal ileum enables assessment of disease activity and extent, severity and histological evaluation (Figure 1). Detailed real-time endoscopic examination can help in delineating between ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), and assessing disease behavior in patients with CD. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy enables assessment and diagnosis of upper GI CD. The diagnosis of CD can be difficult, small bowel and upper gastrointestinal investigations are recommended after ileo-colonscopy[1]. Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) is useful in the diagnosis and evaluation of patients with IBD, especially non-stricturing small bowel disease.

Figure 1.

Common endoscopic findings in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

Endoscopy enables objective measurement of disease response to medical and surgical therapies. Colorectal cancer (CRC) surveillance is imperative in patients with longstanding colonic IBD, except in patients with proctitis or colonic CD limited to only involving one segment of the colorectum[2]. Although essential in the management of patients with IBD, endoscopy is invasive and expensive, placing a burden on patients[3] and healthcare systems. Newer, less invasive tests have not replaced the use of endoscopy in our patients, but rather are used in tandem. Endoscopic ultrasound, and therapeutic endoscopic techniques such as stent placement and balloon dilation are covered elsewhere[4]. This review will focus on paramount roles that endoscopy plays in the management of adults with IBD.

ENDOSCOPIC ASSESSMENT OF DISEASE

Ileo-colonoscopy is the gold standard investigation for the diagnosis of UC and ileo-colonic CD. Real time endoscopic assessment can help delineate between CD and UC, although no endoscopic feature is specific for either. The key features that suggest a diagnosis of CD include perianal disease (careful examination of the perianal region at the time of endoscopy, prior to scope insertion, can reveal fistula tract openings, fissures, strictures and tags), skip lesions, cobblestoning, fistula and strictures, as well as isolated ileal disease. A diagnosis of UC is favoured by continuous colonic inflammation in affected bowel, with obvious demarcation between inflamed and non-inflamed bowel[2]. Patients with UC can be mistaken to have CD secondary to backwash ileitis and “skip lesions”; attributed to a caecal patch[5], charactereised by localized peri-appendiceal inflammation, and from treatment effect giving the impression of a spared distal colon[6]. To avoid this pitfall, it is recommended to document endoscopic features in each colonic segment and terminal ileum at index ileo-colonoscopy, in addition to taking serial segmental biopsies (from affected mucosa and any raised lesions, and normal appearing mucosa)[2,4]. The presence of fistulae and strictures increase the index of suspicion for CD rather than UC, however these need to fully investigated (to outrule mimics and to ensure that a CRC associated with UC is not dismissed).

In patients with acute severe colitis, a flexible sigmoidoscopy without purgatives is recommended as initial endoscopic investigation[2], to confirm the presence, extent and severity of inflammation, to out-rule pseudomembranes (although this may be absent in IBD patients with co-morbid Clostridium difficile infection) and obtain tissue for histological analysis (which is useful to outrule cytomegalovirus infection in immune suppressed patients). Early endoscopic assessment can help identify patients at risk of needing rescue medical therapy[7].

One must be aware of conditions that can masquerade as flares of IBD (Table 1)[8-24]. Endoscopic assessment can be useful; however many conditions such as infective colitis, the findings can be non-specific and overlap with features of IBD. The founding tenets of medical practice: History taking (including a careful drug and travel history) and clinical examination are to be used in tandem with other laboratory, endoscopic and histologic assessment.

Table 1.

Mimics of active inflammatory bowel disease

| Condition | Comment | Ref. |

| ITB | Skip lesions, cobblestoning of mucosa, apthous and linear ulcers are found more frequently in patients with CD compared to ITB | [8,9] |

| Patulous ileocaecal valve, transverse ulcers more common in ITB | [9,10] | |

| Segmental colitis associated with diverticulosis | Inflammatory changes limited to the segment of bowel containing the diverticula with rectal sparing | [11] |

| CMV colitis superimposed in IBD | Mucosal bleeding on light contact, wide mucosal defects and punched out ulcers more common in UC complicated by CMV | [12] |

| The presence of ulcers helps predict CMV in patients with UC but not CD | [13] | |

| Other studies could not identify striking differences on endoscopy | [14] | |

| Biopsies of inflamed mucosa needed assess for inclusion bodies characteristic for CMV colitis | ||

| Clostridium difficle associated disease | Pseudomembranes seldom occur in patients with IBD and Clostridium difficile infection | [15] |

| Campylobacter colitis | Can produce similar appearences to that of UC, detailed endoscopic assessment can help discern from IBD, in addition to stool cultures and biopsies | [16,17] |

| Ischaemic colitis | Typically a segmental disease, with normal mucosa proximal and distal to affected region of colon | [18] |

| Rectum usually spared | [19] | |

| Medication effects | Endoscopic assessment of Ipilimumab induced colitis reveals absent vascular pattern, and erythema in most patients. Variety of endoscopic features described in recent retrospective study | [20] |

| NSAID induced colopathy can affect the whole colon, but has a right sided predominance. Colonic findings include ulceration, strictures and diaphragm like strictures | [21] | |

| Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome | Ulcerative lesions (either single or multiple) most common finding, however can present with erythema or polypoid lesions | [22] |

| Behçet disease | Predilection for ulcers in the ileo-caecal region. Ulcers are typically larger than 1 cm, deep and have discrete margins | [23] |

| Amebic colitis | Endoscopic findings can vary from procto-sigmoiditis to right colonic involvement, biopsy and microscopic identification of Entamoeba species useful in evaluation of suspected amebiasis | [24] |

IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease; ITB: Intestinal tuberculosis; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; CD: Crohn’s disease; NSAID: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

ENDOSCOPIC SCORING SYSTEMS

Endoscopic evaluation is the gold standard to assess objective signs of mucosal inflammation and healing, frequently used in clinical trials. However, inter-observer variability in the assessment of endoscopic findings in patients with IBD has led to the development of several endoscopic scoring systems for both CD and UC, few of which have been validated. Scoring systems aim to interpret endoscopic disease appearance and translate these findings into a quantified score. Baron et al[25] introduced the first scoring system for UC in 1964, they recognised the importance of discontinuous variables in describing endoscopic findings to reduce inter-observer variability[25]. With time numerous other scoring systems[26,27] have been introduced, mainly for use as outcome measures in clinical trials, Table 2 lists some of the commonly used endoscopic indices. Ensuring objective endoscopic evidence of baseline disease activity in clinical trials is associated with reduced placebo remission rates[28,29].

Table 2.

Endoscopic activity indices

| Endoscopic score | Comment | Variables | Ref. |

| Ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity | Easy to use. Scoring based on area of bowel most severely affected. Correlates well with patient reported symptoms | Vascular pattern, bleeding, ulcers/erosions | [83-85] |

| Mayo endoscopic score | Commonly used in clinical practice, four point scale (0-3) (Figure 1) | Vascular pattern, erythema, bleeding, friability, erythema, erosions and ulcers | [86] |

| Modified mayo endoscopic score | Total endoscopic mucosal activity accounted. Easy to use. Correlates well with clinical and histological activity | Combines disease extent with MES severity | [87] |

| Ulcerative colitis colonoscopic index of severity | Total score based on parameters throughout the colon. Validated | Vascular pattern, ulceration, granularity, friability/bleeding | [88] |

| CDEIS | Complex scoring system, time consuming. Validated. Utilised to monitor endoscopic response to treatment | Deep and superficial ulceration, surface of ulcerations, surface of lesions | [33,89] |

| SES-CD | Correlates well with CDEIS and clinical parameters Utilised to monitor endoscopic response to treatment | Ulcer size, stenosis, ulcerated and affected surfaces | [34,90] |

| Rutgeerts’ score | To assess degree of postoperative recurrence at ileo-colonic anastomosis in Crohn’s disease. Easy to use in clinical practice | Apthous ulceration, large ulcers, stenosis, nodularity and ileitis | [30] |

SES-CD: Simple endoscopic score for Crohn’s disease; CDEIS: Crohn’s disease endoscopic index of severity.

Endoscopic scoring systems can be used in clinical practice to identify patients who may benefit from escalation of medical therapy. In acute severe colitis (ASC), the UCEIS helps predict patient outcomes. Nearly 80% of patients admitted to a single institution with ASC, recording a UCEIS score ≥ 7 required rescue medical therapy with infliximab or ciclosporine[7]. When UCEIS was ≥ 5, 33% of patients required colectomy during follow-up, compared with 9% of patients with UCEIS ≤ 4[7].

Early post-operative endoscopic assessment, using the Rutgeert’s score, in patients with CD who undergo intestinal resection is useful in predicting the risk of clinical relapse and need for future surgery[30]. Recent data suggest the Rutgeerts score, which quantifies the degree of recurrent mucosal lesions in the pre-anastomotic ileum, can improve selection of patient’s who require escalation of treatment to reduce risk of post-operative disease recurrence[31]. A recent study escalated treatment of patients with a Rutgeert’s score of i2 or greater, this was associated with significant improvements in mucosal healing and endoscopic recurrence, compared to standard treatment[31]. Prophylactic postoperative Azathioprine use was not superior to endoscopic driven therapy in a study of patients with CD deemed to be high risk for recurrence, in which the primary endpoint was endoscopic remission (i0-i1) at week 102 post-op[32].

Endoscopic response can also help predict patient outcomes. The International Organization for the study of IBD recommends defining endoscopic response as a decrease from baseline in CDEIS or SES-CD score of at least 50%[33]. Mucosal healing and endoscopic response at 26 wk, was predictive of corticosteroid free remission at week 50 in a subgroup analysis of 172 patients from the SONIC trial[34].

CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY

When CD is diagnosed at ileo-colonoscopy, it is recommended to assess the extent of small bowel disease. VCE can be useful in the management of patients with known[35,36] or suspected IBD[37], by visualising mucosa not readily accessible by standard endoscopy. VCE is generally safe in patients with CD[35], the main complication of VCE is that of capsule retention. This can be reduced by excluding patients with known or suspected obstruction, and testing with patency capsule (although recent retrospective study of patients with CD capsule retention was not reduced by use of patency capsule in all patients, compared to selective use of patency capsule[38]). Imaging studies or patency capsule is recommended prior to capsule endoscopy in patients with known small bowel CD[4].

A prospective, multi-centered, blinded cohort study of patients with suspected CD found that VCE is equivalent to ileo-colonoscopy in detecting ileo-caecal inflammation, and is superior to small bowel follow through studies[37]. In patients with suspected inflammatory phenotype CD, VCE is safe and can confirm diagnosis of CD in the presence of a normal ileo-colonoscopy[37]. VCE was superior to MRE and CTE in detecting mucosal lesions proximal to the terminal ileum, in a blinded prospective study of patients with suspected or newly diagnosed CD[39]. However, some authors have suggested that there is a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity with VCE. In particular, while VCE has greater sensitivity for small bowel mucosal lesions in individuals with suspected CD, there is a risk that presence of minor mucosal erosions can give rise to “false positive” diagnosis[40]. This underlines the importance of use of a scoring system (the Lewis index[41], is validated[42] and is comprised of three parameters: stenosis, ulceration and mucosal oedema).

A recent retrospective study of CD patients with isolated small bowel disease, undergoing VCE at diagnosis, found that moderate to severe disease as defined by the Lewis Score[41]; was associated with need for hospitalisation and corticosteroid use after 12 mo follow-up[43]. Conversely a retrospective study of patients with suspected CD, a low Lewis score (defined as < 135) is associated with a low probability CD diagnosis being confirmed on follow-up[44]. VCE also enables assessment of mucosal healing after initiating immunomodulator or biological therapy[45].

VCE may be contraindicated in patients with stricturing CD. MRE and CTE are utilized inpatients with complicated phenotype CD requiring small bowel evaluation, although their use can be limited by patient factors and local availability. Recently the magnetic resonance index of activity has been shown to correlate well with the SES-CD in the assessment of ileal lesions[46].

CRC SURVEILLANCE

Following index endoscopy, endoscopic re-evaluation to guide treatment is typically repeated every few years. Endoscopic surveillance is recommended to commence after 8[2,4,47] to 10[48] years from initial symptoms in patients with colonic disease, as some patients are at increased risk of developing CRC[49]. Patients with extensive colonic disease, concomitant PSC[50], young age at diagnosis, history of sporadic CRC in first degree relative, advanced age[51], severe inflammation[52] and longer duration of disease are at increased risk of developing CRC[53,54]. The optimal surveillance interval is uncertain, the major gastrointestinal societies have differing recommendations[2,4,47,48] but most now increasingly recognize that surveillance efforts are best focused on those at highest risk.

The goal of surveillance is to reduce CRC related mortality and morbidity, by detecting asymptomatic CRC and premalignant lesions. The risk of CRC in patients with IBD is less than previously reported (meta-analysis of population based studies described a pooled standardized incidence ratio of 1.7[53]), and is not increased in all patients. The incidence of CRC in patients with UC has decreased in the last few decades[55]. A nationwide Danish cohort found that patients diagnosed with UC in the 1980s were at increased risk of CRC, however that excessive risk of CRC has declined and no longer exceeds that of the general population[54]. CRC pathogenesis in patients with IBD is thought to occur mainly from dysplasia rather than adenoma to CRC sequence. Patients with colonic CD (3.9%) and UC (6.3%) were found to have reduced risk of developing sporadic adenomatous polyps compared to control population (25.9%)[56]. Interestingly patients with small bowel CD had similar rate of adenomas as control population[56].

The development of flat dysplasia in patients with colonic IBD makes endoscopic surveillance challenging. Traditionally surveillance consisted of numerous random biopsies (4 quadrant biopsies every 10 cm, minimum of 32 biopsies[47]), in addition to any suspicious lesions. The aim of random biopsy sampling is to detect dysplasia, often without visible mucosal abnormalities, before to progresses to CRC. However the principle that dysplasia in patients with IBD occurs usually occurs without visible mucosal abnormalities, has been challenged[57,58].

In patients with UC diagnosed with LGD, risk factors for progression to HGD or CRC include lesions greater than 1 cm, and lesions invisible on endoscopy[59]. Patients with UC were found to have a low risk of progression to CRC after resection of polypoid dysplasia, in a meta-analysis not including any studies using chromoendoscopy[60]. This finding supports current practice of resection and surveillance of raised lesions with dysplasia[49] (although non-adenoma like raised lesions with dysplasia are usually difficult to resect by polypectomy). In a prospective study of patients with undergoing surveillance colonoscopy, CE was superior to random biopsy or WLE in detecting dysplasia[61]. These findings contrast with a large retrospective study, which found no difference between CE and WLE with random and targeted biopsies, in detection rates for dysplasia[62]. Narrow band imaging has not been shown to be superior to white light endoscopy for detecting dysplasia in patients with IBD[63,64]. CE with targeted biopsies are more cost effective than traditional WLE endoscopy with random biopsies[65], and are recommended as preferred method of surveillance in recent guidelines[2,4,48].

The incidence of CRC amongst patients with IBD enrolled in regular surveillance appears to be lower than previously reported[52,66], likely reflecting improvements in medical care and quality of endoscopies performed; with both of this factors benefiting from technological advances. In patients with IBD who develop CRC, those involved in surveillance programmes have better survival rates than those not enrolled in regular surveillance[67].

MUCOSAL HEALING

Clinical remission and endoscopic remission correlate poorly[68], especially in CD. VCE reveals that in patients with small bowel CD in clinical remission, mucosal healing (defined as a Lewis score < 135) is rare[69]. Mucosal healing has become an important treatment target in managing patients with IBD, and is associated with improved outcomes[70,71]. A recent meta-analysis found that mucosa healing was associated with long-term clinical remission, corticosteroid free remission and avoidance of colectomy[71]. Mucosal healing at 26 wk was predictive of corticosteroid free remission at week 50 in a subgroup analysis of 172 patients from the SONIC trial[34]. Considerations influencing the choice of modality to assess mucosal healing are discussed in a recent review[72], colonoscopy is the gold standard in ileo-colonic disease. Faecal calprotectin has been proposed as a surrogate non-invasive marker for mucosal healing, which may rationalize the use of endoscopy in assessing mucosal healing[73]. Faecal markers may not, however, have adequate negative predictive value in all patients, especially those with limited, small bowel disease.

There is a discrepancy between the endoscopic and histological assessment in UC[74], especially mild disease[75]. Endoscopic mucosal healing or inactivity, does not always equate to quiescent microscopic disease[76]. Histological remission is not yet a routinely sought objective in the management of IBD[77], however histological remission better predicts need for hospitisation and corticosteroid use in patients with UC compared to endoscopic remission[78]. A recent prospective study of 179 patients with UC in clinical remission, revealed an association between baseline histology grade and risk of clinical relapse[79]. Patients with an elevated histological grade (Geboes[80] grade ≥ 3.1) at baseline had a relative risk of clinical relapse, over 12 mo follow-up, of 3.5 (95%CI: 1.9-6.4, P < 0.0001)[79]. To aid assessment of histological disease activity in patients with IBD, there needs to be close co-operation between endoscopists and histopathologists[81].

Confocal laser endomicroscopy has the potential to provide real-time microscopic assessment (“endopathology”), which can help predict disease relapse in patients with endoscopic and clinical remission[82].

CONCLUSION

Endoscopy remains integral in the diagnosis and management of IBD, endoscopic disease assessment is essential for objective monitoring of treatment response. Endoscopic severity scores facilitate monitoring of endoscopic response to treatment, and help identify patients who may benefit from escalation of therapy.

The paradigm of CRC surveillance in patients with IBD is shifting from high frequency random biopsies, to that of high quality visual inspection and targeted biopsies of suspected dysplasia, enabled by technological advances including CE and high-definition endoscopes. Current practice in the management of dysplasia entails resection of dysplastic lesions where possible, rather than colectomy.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflict of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Ireland

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: April 5, 2016

First decision: June 12, 2016

Article in press: September 22, 2016

P- Reviewer: Actis GC, Wenzl HH, Yildiz K S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Van Assche G, Dignass A, Panes J, Beaugerie L, Karagiannis J, Allez M, Ochsenkühn T, Orchard T, Rogler G, Louis E, et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:7–27. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Annese V, Daperno M, Rutter MD, Amiot A, Bossuyt P, East J, Ferrante M, Götz M, Katsanos KH, Kießlich R, et al. European evidence based consensus for endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:982–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denters MJ, Schreuder M, Depla AC, Mallant-Hent RC, van Kouwen MC, Deutekom M, Bossuyt PM, Fockens P, Dekker E. Patients’ perception of colonoscopy: patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome experience the largest burden. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:964–972. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328361dcd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shergill AK, Lightdale JR, Bruining DH, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, et al. The role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1101–21.e1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rubin DT, Rothe JA. The peri-appendiceal red patch in ulcerative colitis: review of the University of Chicago experience. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:3495–3501. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1424-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernstein CN, Shanahan F, Anton PA, Weinstein WM. Patchiness of mucosal inflammation in treated ulcerative colitis: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:232–237. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corte C, Fernandopulle N, Catuneanu AM, Burger D, Cesarini M, White L, Keshav S, Travis S. Association between the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity (UCEIS) and outcomes in acute severe ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:376–381. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makharia GK, Srivastava S, Das P, Goswami P, Singh U, Tripathi M, Deo V, Aggarwal A, Tiwari RP, Sreenivas V, et al. Clinical, endoscopic, and histological differentiations between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:642–651. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee YJ, Yang SK, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Chang HS, Hong SS, Kim KJ, Lee GH, Jung HY, Hong WS, et al. Analysis of colonoscopic findings in the differential diagnosis between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease. Endoscopy. 2006;38:592–597. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang T, Fan R, Wang Z, Hu S, Zhang M, Lin Y, Tang Y, Zhong J. Differential diagnosis between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis using integrated parameters including clinical manifestations, T-SPOT, endoscopy and CT enterography. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:17578–17589. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamps LW, Knapple WL. Diverticular disease-associated segmental colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki H, Kato J, Kuriyama M, Hiraoka S, Kuwaki K, Yamamoto K. Specific endoscopic features of ulcerative colitis complicated by cytomegalovirus infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1245–1251. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i10.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCurdy JD, Jones A, Enders FT, Killian JM, Loftus EV, Smyrk TC, Bruining DH. A model for identifying cytomegalovirus in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:131–137; quiz e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iida T, Ikeya K, Watanabe F, Abe J, Maruyama Y, Ohata A, Teruyuki S, Sugimoto K, Hanai H. Looking for endoscopic features of cytomegalovirus colitis: a study of 187 patients with active ulcerative colitis, positive and negative for cytomegalovirus. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1156–1163. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828075ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ben-Horin S, Margalit M, Bossuyt P, Maul J, Shapira Y, Bojic D, Chermesh I, Al-Rifai A, Schoepfer A, Bosani M, et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of endoscopic pseudomembranes in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and Clostridium difficile infection. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:194–198. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mee AS, Shield M, Burke M. Campylobacter colitis: differentiation from acute inflammatory bowel disease. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:217–223. doi: 10.1177/014107688507800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loss RW, Mangla JC, Pereira M. Campylobacter colitis presentin as inflammatory bowel disease with segmental colonic ulcerations. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:138–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandt LJ, Feuerstadt P, Blaszka MC. Anatomic patterns, patient characteristics, and clinical outcomes in ischemic colitis: a study of 313 cases supported by histology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2245–2252; quiz 2253. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sherid M, Sifuentes H, Samo S, Sulaiman S, Husein H, Tupper R, Sethuraman SN, Spurr C, Vainder JA, Sridhar S. Ischemic colitis: A forgotten entity. Results of a retrospective study in 118 patients. J Dig Dis. 2014;15:606–613. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verschuren EC, van den Eertwegh AJ, Wonders J, Slangen RM, van Delft F, van Bodegraven A, Neefjes-Borst A, de Boer NK. Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Characteristics of Ipilimumab-Associated Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:836–842. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aftab AR, Donnellan F, Zeb F, Kevans D, Cullen G, Courtney G. NSAID-induced colopathy. A case series. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:89–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abid S, Khawaja A, Bhimani SA, Ahmad Z, Hamid S, Jafri W. The clinical, endoscopic and histological spectrum of the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a single-center experience of 116 cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:72. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-12-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee CR, Kim WH, Cho YS, Kim MH, Kim JH, Park IS, Bang D. Colonoscopic findings in intestinal Behçet’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001;7:243–249. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200108000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee KC, Lu CC, Hu WH, Lin SE, Chen HH. Colonoscopic diagnosis of amebiasis: a case series and systematic review. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:31–41. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-2040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baron JH, Connell AM, Lennard-jones JE. Variation between observers in describing mucosal appearances in proctocolitis. Br Med J. 1964;1:89–92. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5375.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanna R, Bouguen G, Feagan BG, D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Dubcenco E, Baker KA, Levesque BG. A systematic review of measurement of endoscopic disease activity and mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease: recommendations for clinical trial design. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1850–1861. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samaan MA, Mosli MH, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, D’Haens GR, Dubcenco E, Baker KA, Levesque BG. A systematic review of the measurement of endoscopic healing in ulcerative colitis clinical trials: recommendations and implications for future research. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1465–1471. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jairath V, Zou G, Parker CE, Macdonald JK, Mosli MH, Khanna R, Shackelton LM, Vandervoort MK, AlAmeel T, Al Beshir M, et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: Placebo Rates in Induction and Maintenance Trials of Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:607–618. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, D’Haens G, Pola S, McDonald JW, Rutgeerts P, Munkholm P, Mittmann U, King D, Wong CJ, et al. The role of centralized reading of endoscopy in a randomized controlled trial of mesalamine for ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:149–157.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Beyls J, Kerremans R, Hiele M. Predictability of the postoperative course of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:956–963. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Cruz P, Kamm MA, Hamilton AL, Ritchie KJ, Krejany EO, Gorelik A, Liew D, Prideaux L, Lawrance IC, Andrews JM, et al. Crohn’s disease management after intestinal resection: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1406–1417. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61908-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferrante M, Papamichael K, Duricova D, D’Haens G, Vermeire S, Archavlis E, Rutgeerts P, Bortlik M, Mantzaris G, Van Assche G. Systematic versus Endoscopy-driven Treatment with Azathioprine to Prevent Postoperative Ileal Crohn’s Disease Recurrence. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:617–624. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vuitton L, Marteau P, Sandborn WJ, Levesque BG, Feagan B, Vermeire S, Danese S, D’Haens G, Lowenberg M, Khanna R, et al. IOIBD technical review on endoscopic indices for Crohn’s disease clinical trials. Gut. 2016;65:1447–1455. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferrante M, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, Lichtiger S, D’Haens GR, van der Woude CJ, et al. Validation of endoscopic activity scores in patients with Crohn’s disease based on a post hoc analysis of data from SONIC. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:978–986.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kopylov U, Nemeth A, Koulaouzidis A, Makins R, Wild G, Afif W, Bitton A, Johansson GW, Bessissow T, Eliakim R, et al. Small bowel capsule endoscopy in the management of established Crohn’s disease: clinical impact, safety, and correlation with inflammatory biomarkers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:93–100. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Long MD, Barnes E, Isaacs K, Morgan D, Herfarth HH. Impact of capsule endoscopy on management of inflammatory bowel disease: a single tertiary care center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1855–1862. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leighton JA, Gralnek IM, Cohen SA, Toth E, Cave DR, Wolf DC, Mullin GE, Ketover SR, Legnani PE, Seidman EG, et al. Capsule endoscopy is superior to small-bowel follow-through and equivalent to ileocolonoscopy in suspected Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:609–615. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koulaouzidis A, Sipponen T, Nemeth A, Makins R, Kopylov U, Nadler M, Giannakou A, Yung DE, Johansson GW, Bartzis L, et al. Association Between Fecal Calprotectin Levels and Small-bowel Inflammation Score in Capsule Endoscopy: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:2033–2040. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jensen MD, Nathan T, Rafaelsen SR, Kjeldsen J. Diagnostic accuracy of capsule endoscopy for small bowel Crohn’s disease is superior to that of MR enterography or CT enterography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:124–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doherty GA, Moss AC, Cheifetz AS. Capsule endoscopy for small-bowel evaluation in Crohn’s disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gralnek IM, Defranchis R, Seidman E, Leighton JA, Legnani P, Lewis BS. Development of a capsule endoscopy scoring index for small bowel mucosal inflammatory change. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cotter J, Dias de Castro F, Magalhães J, Moreira MJ, Rosa B. Validation of the Lewis score for the evaluation of small-bowel Crohn’s disease activity. Endoscopy. 2015;47:330–335. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dias de Castro F, Boal Carvalho P, Monteiro S, Rosa B, Firmino-Machado J, Moreira MJ, Cotter J. Lewis Score--Prognostic Value in Patients with Isolated Small Bowel Crohn’s Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:1146–1151. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monteiro S, Boal Carvalho P, Dias de Castro F, Magalhães J, Machado F, Moreira MJ, Rosa B, Cotter J. Capsule Endoscopy: Diagnostic Accuracy of Lewis Score in Patients with Suspected Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2241–2246. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hall B, Holleran G, Chin JL, Smith S, Ryan B, Mahmud N, McNamara D. A prospective 52 week mucosal healing assessment of small bowel Crohn’s disease as detected by capsule endoscopy. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1601–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takenaka K, Ohtsuka K, Kitazume Y, Nagahori M, Fujii T, Saito E, Fujioka T, Matsuoka K, Naganuma M, Watanabe M. Correlation of the Endoscopic and Magnetic Resonance Scoring Systems in the Deep Small Intestine in Crohn’s Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1832–1838. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, Itzkowitz SH, McCabe RP, Dassopoulos T, Lewis JD, Ullman TA, James T, McLeod R, et al. AGA medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:738–745. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cairns SR, Scholefield JH, Steele RJ, Dunlop MG, Thomas HJ, Evans GD, Eaden JA, Rutter MD, Atkin WP, Saunders BP, et al. Guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and surveillance in moderate and high risk groups (update from 2002) Gut. 2010;59:666–689. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.179804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Laine L, Kaltenbach T, Barkun A, McQuaid KR, Subramanian V, Soetikno R. SCENIC international consensus statement on surveillance and management of dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:639–651.e28. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng HH, Jiang XL. Increased risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis of 16 observational studies. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:383–390. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang YR, Cangemi JR, Loftus EV, Picco MF. Rate of early/missed colorectal cancers after colonoscopy in older patients with or without inflammatory bowel disease in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:444–449. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm MA, Williams CB, Price AB, Talbot IC, Forbes A. Thirty-year analysis of a colonoscopic surveillance program for neoplasia in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1030–1038. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lutgens MW, van Oijen MG, van der Heijden GJ, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD, Oldenburg B. Declining risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: an updated meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:789–799. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828029c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jess T, Simonsen J, Jørgensen KT, Pedersen BV, Nielsen NM, Frisch M. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:375–781.e1; quiz e13- e 14. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castaño-Milla C, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the declining risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:645–659. doi: 10.1111/apt.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ben-Horin S, Izhaki Z, Haj-Natur O, Segev S, Eliakim R, Avidan B. Rarity of adenomatous polyps in ulcerative colitis and its implications for colonic carcinogenesis. Endoscopy. 2016;48:215–222. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1393119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van den Broek FJ, Stokkers PC, Reitsma JB, Boltjes RP, Ponsioen CY, Fockens P, Dekker E. Random biopsies taken during colonoscopic surveillance of patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis: low yield and absence of clinical consequences. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:715–722. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rubin DT, Rothe JA, Hetzel JT, Cohen RD, Hanauer SB. Are dysplasia and colorectal cancer endoscopically visible in patients with ulcerative colitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:998–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Choi CH, Ignjatovic-Wilson A, Askari A, Lee GH, Warusavitarne J, Moorghen M, Thomas-Gibson S, Saunders BP, Rutter MD, Graham TA, et al. Low-grade dysplasia in ulcerative colitis: risk factors for developing high-grade dysplasia or colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1461–1471; quiz 1472. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wanders LK, Dekker E, Pullens B, Bassett P, Travis SP, East JE. Cancer risk after resection of polypoid dysplasia in patients with longstanding ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:756–764. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Marion JF, Waye JD, Israel Y, Present DH, Suprun M, Bodian C, Harpaz N, Chapman M, Itzkowitz S, Abreu MT, et al. Chromoendoscopy Is More Effective Than Standard Colonoscopy in Detecting Dysplasia During Long-term Surveillance of Patients With Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mooiweer E, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Ponsioen CY, Fidder HH, Siersema PD, Dekker E, Oldenburg B. Chromoendoscopy for Surveillance in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Does Not Increase Neoplasia Detection Compared With Conventional Colonoscopy With Random Biopsies: Results From a Large Retrospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1014–1021. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ignjatovic A, East JE, Subramanian V, Suzuki N, Guenther T, Palmer N, Bassett P, Ragunath K, Saunders BP. Narrow band imaging for detection of dysplasia in colitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:885–890. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leifeld L, Rogler G, Stallmach A, Schmidt C, Zuber-Jerger I, Hartmann F, Plauth M, Drabik A, Hofstädter F, Dienes HP, et al. White-Light or Narrow-Band Imaging Colonoscopy in Surveillance of Ulcerative Colitis: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1776–1781.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Konijeti GG, Shrime MG, Ananthakrishnan AN, Chan AT. Cost-effectiveness analysis of chromoendoscopy for colorectal cancer surveillance in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:455–465. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mooiweer E, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, Ponsioen CY, van der Woude CJ, van Bodegraven AA, Jansen JM, Mahmmod N, Kremer W, Siersema PD, Oldenburg B. Incidence of Interval Colorectal Cancer Among Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients Undergoing Regular Colonoscopic Surveillance. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1656–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lutgens MW, Oldenburg B, Siersema PD, van Bodegraven AA, Dijkstra G, Hommes DW, de Jong DJ, Stokkers PC, van der Woude CJ, Vleggaar FP. Colonoscopic surveillance improves survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis in inflammatory bowel disease. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1671–1675. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Diamond R, Rutgeerts P, Tang LK, Cornillie FJ, Sandborn WJ. Clinical disease activity, C-reactive protein normalisation and mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease in the SONIC trial. Gut. 2014;63:88–95. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kopylov U, Yablecovitch D, Lahat A, Neuman S, Levhar N, Greener T, Klang E, Rozendorn N, Amitai MM, Ben-Horin S, et al. Detection of Small Bowel Mucosal Healing and Deep Remission in Patients With Known Small Bowel Crohn’s Disease Using Biomarkers, Capsule Endoscopy, and Imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1316–1323. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shah SC, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Narula N. Systematic review with meta-analysis: mucosal healing is associated with improved long-term outcomes in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:317–333. doi: 10.1111/apt.13475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shah SC, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Narula N. Mucosal Healing Is Associated With Improved Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1245–1255.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dulai PS, Levesque BG, Feagan BG, D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ. Assessment of mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:246–255. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.03.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Theede K, Holck S, Ibsen P, Ladelund S, Nordgaard-Lassen I, Nielsen AM. Level of Fecal Calprotectin Correlates With Endoscopic and Histologic Inflammation and Identifies Patients With Mucosal Healing in Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1929–36.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guardiola J, Lobatón T, Rodríguez-Alonso L, Ruiz-Cerulla A, Arajol C, Loayza C, Sanjuan X, Sánchez E, Rodríguez-Moranta F. Fecal level of calprotectin identifies histologic inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical and endoscopic remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1865–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lemmens B, Arijs I, Van Assche G, Sagaert X, Geboes K, Ferrante M, Rutgeerts P, Vermeire S, De Hertogh G. Correlation between the endoscopic and histologic score in assessing the activity of ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1194–1201. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e318280e75f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rosenberg L, Nanda KS, Zenlea T, Gifford A, Lawlor GO, Falchuk KR, Wolf JL, Cheifetz AS, Goldsmith JD, Moss AC. Histologic markers of inflammation in patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:991–996. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bryant RV, Winer S, Travis SP, Riddell RH. Systematic review: histological remission in inflammatory bowel disease. Is ‘complete’ remission the new treatment paradigm? An IOIBD initiative. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1582–1597. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, Walsh AJ, Thomas S, von Herbay A, Buchel OC, White L, Brain O, Keshav S, et al. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up. Gut. 2016;65:408–414. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zenlea T, Yee EU, Rosenberg L, Boyle M, Nanda KS, Wolf JL, Falchuk KR, Cheifetz AS, Goldsmith JD, Moss AC. Histology Grade Is Independently Associated With Relapse Risk in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis in Clinical Remission: A Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:685–690. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Geboes K, Riddell R, Ost A, Jensfelt B, Persson T, Löfberg R. A reproducible grading scale for histological assessment of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2000;47:404–409. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Marchal Bressenot A, Riddell RH, Boulagnon-Rombi C, Reinisch W, Danese S, Schreiber S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Review article: the histological assessment of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:957–967. doi: 10.1111/apt.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Buda A, Hatem G, Neumann H, D’Incà R, Mescoli C, Piselli P, Jackson J, Bruno M, Sturniolo GC. Confocal laser endomicroscopy for prediction of disease relapse in ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Travis SP, Schnell D, Krzeski P, Abreu MT, Altman DG, Colombel JF, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lémann M, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Developing an instrument to assess the endoscopic severity of ulcerative colitis: the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) Gut. 2012;61:535–542. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Travis SP, Schnell D, Krzeski P, Abreu MT, Altman DG, Colombel JF, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, Marteau PR, et al. Reliability and initial validation of the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:987–995. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Travis SP, Schnell D, Feagan BG, Abreu MT, Altman DG, Hanauer SB, Krzeski P, Lichtenstein GR, Marteau PR, Mary JY, et al. The Impact of Clinical Information on the Assessment of Endoscopic Activity: Characteristics of the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index Of Severity [UCEIS] J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:607–616. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625–1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198712243172603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lobatón T, Bessissow T, De Hertogh G, Lemmens B, Maedler C, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Bisschops R, Rutgeerts P, Bitton A, et al. The Modified Mayo Endoscopic Score (MMES): A New Index for the Assessment of Extension and Severity of Endoscopic Activity in Ulcerative Colitis Patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:846–852. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Samuel S, Bruining DH, Loftus EV, Thia KT, Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Faubion WA, Kane SV, Pardi DS, de Groen PC, et al. Validation of the ulcerative colitis colonoscopic index of severity and its correlation with disease activity measures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:49–54.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mary JY, Modigliani R. Development and validation of an endoscopic index of the severity for Crohn’s disease: a prospective multicentre study. Groupe d’Etudes Thérapeutiques des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID) Gut. 1989;30:983–989. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.7.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Daperno M, D’Haens G, Van Assche G, Baert F, Bulois P, Maunoury V, Sostegni R, Rocca R, Pera A, Gevers A, et al. Development and validation of a new, simplified endoscopic activity score for Crohn’s disease: the SES-CD. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:505–512. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01878-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]