Introduction

The immune checkpoint molecule programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) was discovered in 1992 by Professor Tasuku Honjo and his research team at Kyoto University [1]. They later discovered that PD-1 is involved in immunosuppression and is a receptor that acts as a “brake” for the immune response in knockout mice. In 2000, a joint research project between the Honjo group at Kyoto University and the Genetics Institute together with Harvard University discovered the ligands of PD-1 (PD-L1 and PD-L2) [2,3,4,5]. In 2002, Iwai et al. [6] found that enhancing immune activation by inhibiting the binding of PD-1 to its ligands in mouse models markedly enhanced antitumor activity. In 2005, Ono Pharmaceutical and the American company Medarex took note of these findings and developed nivolumab, a human anti-PD-1 antibody. That same year, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognized nivolumab as an investigational new drug, thereby enabling clinical trials to be started in the United States. In 2009, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Ono Pharmaceutical (BMS/ONO) began joint clinical trials of nivolumab. The results of clinical trials in patients with melanoma led to the approval of an anti-PD-1 antibody for the treatment of melanoma in Japan in July 2014, before any other country in the world. Nivolumab has also been evaluated in a series of clinical trials for non-small cell lung cancer and renal cell carcinoma and has yielded favorable outcomes.

In 1995, Dr. James Allison of the University of Texas discovered that another molecule, called cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen (CTLA-4) [7], serves as an indicator of immune cell suppression [7]. In 1996, his team showed that tumors disappeared in mice treated with an antibody that inhibits the function of CTLA-4 [8]. CTLA-4 is also an immune checkpoint molecule. Bristol-Myers developed an anti-CTLA-4 antibody called ipilimumab, which was approved for the treatment of melanoma in the United States in March 2011 and in Europe in July 2011 [9]. It was later approved in Japan in July 2015.

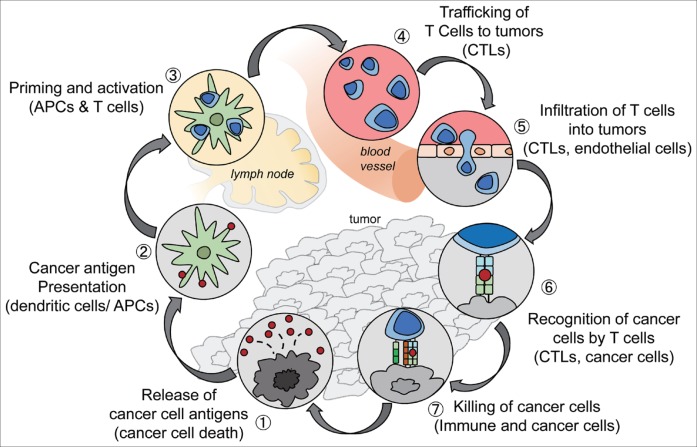

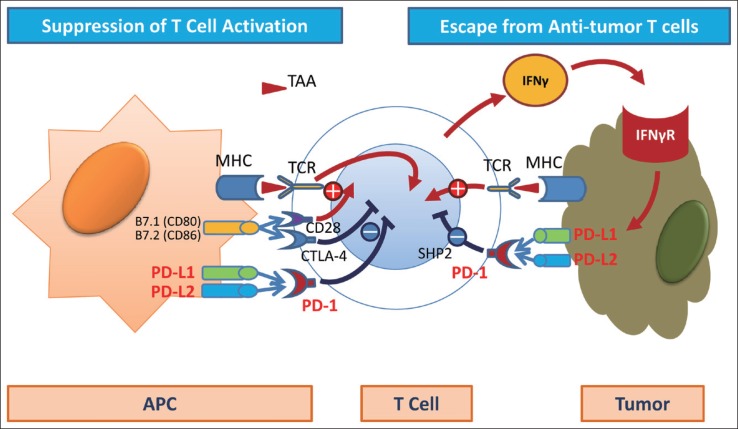

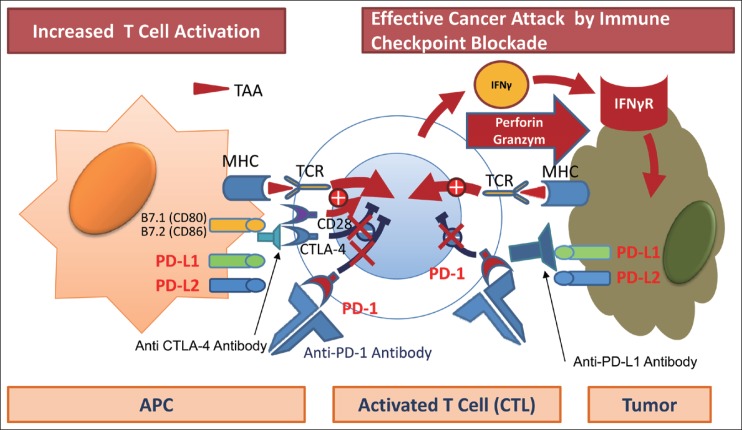

When cancer cells develop, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) recognize tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), triggering in the lymph nodes the activation of immature T cells that will become CD8-positive T cells (the priming phase). Once activated, the T cells travel throughout the bloodstream and reach the tumor site. There, they attempt to attack tumor cells by releasing molecules such as perforin and granzymes (the effector phase) (fig 1) [10]. Moreover, recognition of TAAs by T cell receptors (TCR) triggers the release of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and other cytokines by CD8-positive T cells in an attempt to attack the cancer. However, tumor cells protect themselves by expressing IFN-γ induced PD-L1 or PD-L2, which binds to PD-1. When this happens, PD-1/PD-L1 binding attenuate the antitumor immune response, thereby weakening the attacking power of the T cells. This is called immune escape or immune tolerance (fig. 2). The anti-PD-1 antibody blocks PD-1 on activated T cells from binding to PD-L1 or PD-L2 on APCs or tumor cells. This removes the “brake” on the immune system and restores the ability of T cells to attack tumor cells (fig. 3). Unlike conventional chemotherapy or molecular targeted therapy, anti-PD-1 antibody achieves its antitumor effect by restoring the original potential of the natural human immune system as a powerful and precise weapon against cancer cells [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Antibodies against PD-L1 expression in the cancer tissue are believed to have a similar effect [23]. The recognition of “immuno-oncology” using immune checkpoint inhibitors was considered the “Breakthrough of the Year” by the American journal Science in 2013, and immuno-oncology has been widely publicized. PD-L1 also serves as a biomarker that predicts the response to anti-PD-1 antibody [24]. In addition, Kupffer-phase Sonazoid contrast-enhanced ultrasonography is an effective imaging method for predicting the response to treatment with anti-PD-1 antibody [25].

Fig. 1.

The cancer-immunity cycle. The generation of immunity to cancer is a cyclic process that leads to an accumulation of immune-stimulatory factors. This cycle can be divided into seven major steps, starting with the release of antigens from cancer cells and ending with the killing of cancer cells. CTLs=cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Reproduced with permission from Chen DS, et al. [10]

Fig. 2.

Immune checkpoint molecule: PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA-4. Immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-1, PD-L1, and CTLA-4 play an important role in the immune escape of cancer cells from activated CD8-positive T cells. MHC=major histocompatibility complex; IFNγR=interferon gamma receptor.

Fig. 3.

Immune checkpoint blockade: anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti CTLA-4 antibody. Anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies restore cytotoxic T cell activity, resulting in tumor attack by perforin and granzyme.

Development of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

Promising results from an interim analysis of a phase I/II trial of the anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab (CheckMate-040 trial dose-escalation cohort) were presented at the 2015 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting held in Chicago [26,27]. This dose-escalation study demonstrated the safety of nivolumab at doses of 3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg in HCC patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, patients with hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, and uninfected patients. The interim results of the dose-escalation study also demonstrated the efficacy of nivolumab at doses ranging from 0.1 to 10 mg/kg. Of the 47 patients included in the study, 33 (70%) had extrahepatic metastasis, 6 (13%) had vascular invasion, and 32 (68%) had previously been treated with sorafenib, i.e., the study population had relatively advanced cancer. Patients were treated with anti-PD-1 antibody, and an interim analysis was performed on March 12, 2015. At that point, 17 patients were still receiving treatment and 30 had completed or discontinued treatment. The reasons for discontinuation were disease progression in 26 patients, complete response (CR) in two patients, and adverse events in two patients. The adverse events leading to discontinuation were increased bilirubin (n=1) and an event unrelated to the study drug (n=1). The only grade 4 event (graded using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events) was increased lipase, and the only grade 3 events were elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels in five patients (11%) and elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in four patients (9%). No serious liver dysfunction or autoimmune disease was reported.

The response rate was 19% (n=8), including the two CRs (5%). The disease control rate (DCR) was also very favorable: 67% of patients (n=28) maintained stable disease (SD) or better, whereas only 33% (n=14) developed progressive disease (PD).

Waterfall plots showed that the tumor size decreased to some extent in all cohorts (i.e., un-infected, HBV-infected, and HCV-infected HCC patients). The durability of treatment responses is particularly noteworthy. The two patients who had a CR achieved it within 3 months and maintained it for 18 months. Another patient who showed a partial response (PR) (almost a CR in fact) showed SD at approximately 11 months while the PR occurred at approximately 13 months. A durable response was achieved in all patients with a PR or SD, and no patient developed PD because of resistance. In summary, treatment of liver cancer with anti-PD-1 antibody yielded a durable response comparable to that achieved in other types of cancer. This property is highly characteristic of immune checkpoint inhibitors and merits attention. The two patients who had a CR achieved it within 3 months and maintained the response for 18 months or longer, even after discontinuing the anti-PD-1 antibody a few months after the CR. Almost all patients who showed a PR achieved it within 3 months of treatment. One of the cases presented at ASCO 2015 was a patient with countless bilobar HCCs, all of which resolved completely after 6 weeks; this was accompanied by a decrease in alpha-fetoprotein from 21,000 to 283 ng/ml. Another patient showed a decrease in tumor size from 10 cm to about 2 cm after 48 weeks, which demonstrates the durability of the response. The overall 12-month survival rate was a favorable 62%, which is a very promising outcome considering the unfavorable tumor characteristics of the study population.

The interim results of this trial can be summarized in three points: First, monotherapy with the anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab has a favorable safety profile for HCC that is comparable with its safety profile for the treatment of other types of cancer. Second, nivolumab can be used safely in patients infected with HBV or HCV. Third, immunotherapy yields both a very high response rate and a durable response. This long-lasting effect was observed at all dose levels and in all cohorts (uninfected, HBV-infected, and HCV-infected).

The team conducting this phase I/II trial designed an expansion study using a fixed dose of 3 mg/kg of nivolumab in three cohorts as follows: patients with no HBV or HCV infection who were sorafenib-naïve (n=50) or who had developed PD after treatment with sorafenib (n=50); HCV-infected patients (n=50); and HBV-infected patients (n=50). The results of the expansion study and the final results from the dose-escalation study were presented at ASCO 2016.

Clinical Trials in Progress

According to the results presented at ASCO 2016, 35 of the 214 patients (16%) in the expansion cohort (CheckMate-040 cohort 2) had a tumor response [28] (table 1). The response rate was 20% for uninfected sorafenib-naïve or sorafenib-intolerant HCC patients, 19% for uninfected sorafenib-treated patients with PD, 14% for HCV-infected patients, and 12% for HBV-infected patients. The 9-month survival rate was a favorable 70.8%. Grade 3–4 adverse events of elevated AST and ALT levels were observed in this expansion cohort at low rates of 6% (13/139) and 7% (15/139), respectively (table 2). Considering that 66% of the 214 patients had been previously treated with sorafenib, and a high percentage of patients had advanced cancer, a 9-month survival rate of 70.8% is an excellent result (tables 3, 4).

Table 1.

CheckMate 040 dose-expansion cohort (n=214) investigator-assessed best overall response (RECIST v1.1)

| Uninfected: sorafenib naïve/ intolerant (n=54) | Uninfected: sorafenib progressors (n=58) | HCV (n=51) | HBV (n=51) | Total (n=214) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective response, n (%) | 11 (20) | 11 (19) | 7 (14) | 6 (12) | 35 (16) |

| CR | 0 | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) |

| PR | 11 (20) | 9 (16) | 7 (14) | 6 (12) | 33 (15) |

| SD | 32 (59) | 27 (47) | 29 (57) | 23 (45) | 111 (52) |

| PD | 11 (20) | 18 (31) | 12 (24) | 22 (43) | 63 (29) |

| Not evaluable | 0 | 2 (3) | 3 (6) | 0 | 5 (2) |

RECIST=response evaluation criteria in solid tumors. Reproduced with permission from Sangro B, et al. [28]

Table 2.

CheckMate 040 dose-expansion cohort (n=214) treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs)

| Uninfected (n=112) | HCV (n=51) | HBV (n=51) | Total (n=214) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade 3–4 | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | Any grade | Grade 3–4 | |

| Patients with any TRAE, n (%) | 72 (64) | 21 (19) | 37 (73) | 15 (29) | 30 (59) | 3 (6) | 139 (65) | 39 (18) |

| Symptomatic TRAEs reported in >4% of all patients | ||||||||

| Fatigue | 31 (28) | 2 (2) | 7 (14) | 0 | 7 (14) | 0 | 45 (21) | 2 (1) |

| Pruritus | 11 (10) | 0 | 11 (22) | 0 | 11 (22) | 0 | 33 (15) | 0 |

| Rash | 12 (11) | 1 (1) | 8 (16) | 0 | 6 (12) | 0 | 26 (12) | 1 (0.5) |

| Diarrhea | 16 (14) | 2 (2) | 3 (6) | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 20 (9) | 3 (1) |

| Nausea | 8 (7) | 0 | 6 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (7) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 5 (5) | 0 | 2 (4) | 0 | 3 (6) | 0 | 10 (5) | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 5 (4) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (4) | 0 | 8 (4) | 0 |

| Laboratory-value TRAEs reported in >4% of all patients | ||||||||

| ALT increased | 6 (5) | 2 (2) | 7 (14) | 4 (8) | 2 (4) | 0 | 15 (7) | 6 (3) |

| AST increased | 7 (6) | 3 (3) | 6 (12) | 6 (12) | 0 | 0 | 13 (6) | 9 (4) |

| Platelet count decreased | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | 5 (10) | 1 (2) | 8 (4) | 3 (1) |

| Anemia | 2 (2) | 0 | 3 (6) | 1 (2) | 3 (6) | 0 | 8 (4) | 1 (0.5) |

Reproduced with permission from Sangro B, et al. [28]

Table 3.

CheckMate 040 dose-expansion cohort (n=214) baseline patient characteristics and prior treatment history

| Uninfected: sorafenib naïve/intolerant (n=54) | Uninfected: sorafenib progressors (n=58) | HCV (n=51) | HBV (n=51) | Total (n=214) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 66 (20–83) | 65 (19–80) | 65 (53–81) | 55 (22–81) | 64 (19–83) |

| Male, n (%) | 46 (85) | 43 (74) | 43 (84) | 39(77) | 171 (80) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||

| White | 36 (67) | 35 (60) | 30 (59) | 4 (8) | 105 (49) |

| Black/African American | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | 6 (3) |

| Asian | 16 (30) | 22 (38) | 18 (35) | 45 (88) | 101 (47) |

| Other | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Extrahepatic metastases, n (%) | 42 (78) | 43 (74) | 30 (59) | 46 (90) | 161 (75) |

| Vascular invasion, n (%) | 1 (2) | 3 (5) | 5 (10) | 6 (12) | 15 (7) |

| Child-Pugh score, n (%) | |||||

| 5 | 41 (76) | 38 (66) | 27 (53) | 44 (86) | 150 (70) |

| 6 | 12 (22) | 20 (34) | 21 (41) | 7 (14) | 60 (28) |

| 7 | 1 (2) | 0 | 2 (4) | 0 | 3 (1) |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (0.5) |

| α-Fetoprotein >200 μg/L, n (%) | 15 (28) | 26 (45) | 18 (35) | 27 (53) | 86 (40) |

| Prior treatment type, n (%) | |||||

| Surgical resection | 29 (54) | 37 (64) | 19 (37) | 40 (78) | 125 (58) |

| Radiotherapy | 7 (13) | 17 (29) | 5 (10) | 12 (24) | 41 (19) |

| Local treatment for HCC | 25 (46) | 33 (57) | 29 (57) | 40 (78) | 127 (59) |

| Systemic therapy | 22 (41) | 57 (98) | 32 (63) | 46 (90) | 157 (73) |

| Sorafenib | 15 (28) | 56 (97) | 30 (59) | 40 (78) | 141 (66) |

Reproduced with permission from Sangro B, et al. [28]

Table 4.

CheckMate 040 dose-expansion cohort (n=214) overall survival rates

| Survival rate, %(95% Cl)a | Uninfected: sorafenib naïve/intolerant (n=54) | Uninfected: sorafenib progressors (n=58) | HCV (n=51) | HBV (n=51) | Total (n=214) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-Month | 89.8 (77.1, 95.6) | 75.6 (61.5, 85.2) | 82.1 (61.3, 92.4) | 83.3 (67.6, 91.8) | 82.5 (75.8, 87.5) |

| 9-Month | 79.8 (50.6, 92.8) | NC | NC | NC | 70.8 (56.6, 81.1) |

Estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Cl=confidence interval; NC=not calculated. Reproduced with permission from Sangro B, et al. [28]

The results of additional analysis of the dose-escalation cohort of 48 patients (Check-Mate-040 cohort 1) showed a tumor response in seven patients (15%); the response rate was 13% in the uninfected group, 30% in the HCV-infected group, and 7% in the HBV-infected group [29] (tables 5, 6, 7).

Table 5.

CheckMate 040 dose-escalation cohort (n=48) baseline patient characteristics and prior treatment history

| Uninfected (n=23) | HCV (n=10) | HBV (n=15) | Total (n=48) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 61 (22–79) | 67 (55–83) | 62 (41–75) | 62 (22–83) |

| ≥65 years, n (%) | 8 (35) | 6 (60) | 6 (40) | 20 (42) |

| Male, n (%) | 17 (74) | 6 (60) | 13 (87) | 36 (75) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 19 (83) | 8 (80) | 1 (7) | 28 (58) |

| Asian | 2 (9) | 2 (17) | 14 (88) | 18 (38) |

| Black | 2 (9) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4) |

| Extrahepatic metastases, n (%) | 18 (78) | 6 (60) | 13 (87) | 37 (77) |

| Vascular invasion, n (%) | 3 (13) | 1 (10) | 2 (13) | 6 (13) |

| Child-Pugh score, n (%) | ||||

| 5 | 19 (83) | 8 (80) | 14 (93) | 41 (85) |

| 6 | 4 (17) | 2 (20) | 1 (7) | 7 (15) |

| α-Fetoprotein >200 μg/L, n (%) a | 8 (35) | 3 (30) | 8 (53) | 19 (40) |

| Prior treatment type, n (%) | ||||

| Surgical resection | 15 (65) | 8 (80) | 13 (87) | 36 (75) |

| Radiotherapy b (external or internal) | 6 (26) | 2 (20) | 2 (13) | 10 (21) |

| Local treatment for HCC c | 11 (48) | 8 (80) | 12 (80) | 31 (65) |

| Systemic therapy | 18 (78) | 6 (60) | 15 (100) | 39 (81) |

| Sorafenib | 16 (70) | 5 (50) | 14 (93) | 35 (73) |

Baseline α-fetoprotein values were missing for one uninfected patient;

Could include radioembolization;

TACE, RFA, or percutaneous ethanol injection. Reproduced with permission from El-Khoueiry AB, et al. [29]

Table 6.

CheckMate 040 dose-escalation cohort (n=48) TRAE

| Total (n=48) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade 3–4 | |

| Patients with any TRAE, n (%) | 38 (79) | 12 (25) |

| Symptomatic TRAEs reported in >5% of all patients, n (%) | ||

| Rash | 11 (23) | 0 |

| Pruritus | 7 (15) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 4 (8) | 0 |

| Asthenia | 3 (6) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 3 (6) | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 3 (6) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 3 (6) | 1 (2) |

| Laboratory-value TRAEs reported in >5% of all patients, n (%) | ||

| AST increased | 10 (21) | 5 (10) |

| Lipase increased | 10 (21) | 6 (13) |

| Amylase increased | 9 (19) | 1 (2) |

| ALT increased | 7 (15) | 3 (6) |

| Anemia | 3 (6) | 1 (2) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 3 (6) | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 3 (6) | 0 |

Reproduced with permission from El-Khoueiry AB, et al. [29]

Table 7.

CheckMate 040 dose-escalation cohort (n=48) investigator-assessed best overall response (RE CIST v1.1)

| Uninfected (n=23) | HCV (n=10) | HBV (n=15) | Total (n=48) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Objective response, n (%) | 3 (13) | 3 (30) | 1 (7) | 7 (15) |

| CR | 2 (9) | 1 (10) | 0 | 3 (6) |

| PR | 1 (4) | 2 (20) | 1 (7) | 4 (8) |

| SD | 13(57) | 5 (50) | 6 (40) | 24 (50) |

| PD | 6 (26) | 2 (20) | 7 (47) | 15 (31) |

| Not evaluable | 1 (4) | 0 | 1 (7) | 2 (4) |

| Ongoing response, n (%) | 1 (33) | 0 | 0 | 1 (14) |

Reproduced with permission from El-Khoueiry AB, et al. [29]

The team conducting this phase I/II trial in addition to cohort 1 and 2, a randomized controlled study comparing nivolumab with sorafenib (cohort 3), a study of combination therapy with the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab (cohort 4), and a study of nivolumab in Child-Pugh B patients (cohort 5).

Other ongoing trials include the dose-expansion study (cohort 2), a phase III trial comparing first-line nivolumab (anti-PD-L1 antibody) with sorafenib, a phase III trial of pembrolizumab as second-line therapy after sorafenib failure, and a phase II trial of combination therapy with the anti-PD-L1 antibody durvalumab and the anti-CTLA-4 antibody tremelimumab (table 8). The results of a clinical trial of an anti-CTLA-4 antibody for the treatment of HCC were published in the Journal of Hepatology in 2013. However, the anti-CTLA-4 antibody

Table 8.

Current trials of immune checkpoint inhibitors

| Drug | Trial name | Clinicaltrials.gov | Company | Phase | n | Line of therapy | Design | Endpoint | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nivolumab | |||||||||

| Nivolumab (PD-1 Ab]/ipilimumab (PD-L1 Ab] | CheckMate 040 | NCT01658878 | BMS/ONO | I/II | 42 | 1l/2l | Cohort 1: Dose escalation | DLT/MTD | Completed |

| CheckMate 040 | NCT01658878 | BMS/ONO | I/II | 214 | 1l/2l | Cohort 2: Dose expansion | ORR | Completed | |

| CheckMate 040 | NCT01658878 | BMS/ONO | I/II | 200 | 1l | Cohort 3: Nivolumab vs sorafenib | ORR | Completed | |

| CheckMate 040 | NCT01658878 | BMS/ONO | I/II | 120 | 2l | Cohort 4: Nivolumab + ipilimumab | Safety/tolerability | Completed | |

| Nivolumab (PD-1 Ab] | CheckMate 459 | NCT02576509 | ONO | III | 726 | 1l | Nivolumab vs sorafenib | TTP/OS | Recruiting |

| Pembrolizumab | |||||||||

| Pembrolizumab (PD-1 Ab] | KEYNOTE-224 | NCT02702414 | MSD | II | 100 | 2l | Pembrolizumab (1 arm] | ORR | Completed |

| Pembrolizumab (PD-1 Ab] | KEYNOTE-240 | NCT02702401 | MSD | III | 408 | 2l | Pembrolizumab vs placebo | PFS/OS | Recruiting |

| Durvalumab | |||||||||

| Durvalumab (PD-L1 Ab]/tremelimumab (CTLA-4 Ab] | – | NCT02519348 | AstraZeneca | II | 144 | 1l/2l | Durvalumab (Arm A] Tremelimumab (Arm B] Durvalumab + tremelimumab (Arm C] | Safety/tolerability | Recruiting |

DLT/MTD=dose-limiting toxicity/maximum tolerated dose; ORR=overall response rate; TTP/OS=time to progression/overall survival; PFS=progression-free survival.

Future Perspectives

The previously described interim analysis results from the phase I/II trial for HCC (dose-expansion cohort) that were presented at ASCO 2016 involved monotherapy with anti-PD-1 antibody. The anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab has been approved for certain malignancies, including melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer, and kidney cancer, and is expected to yield favorable outcomes in ongoing trials for many other types of cancer [31,32,33,34,35,36]. HCC requires different treatment strategies compared with other solid tumors or hematologic malignancies because it is extremely heterogeneous, does not have any major driver mutations, and cannot be treated with drugs that reduce hepatic functional reserve. The outcomes of this phase I/II dose-expansion trial indicate that the anti-PD-1 antibody is a promising treatment for HCC.

Additionally, as mentioned in the previous section, many pharmaceutical companies have started phase III trials and other early phase clinical trials of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody for the treatment of HCC, the results of which are eagerly awaited.

There are unmet needs in HCC management in various settings, including neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy with resection or ablation, combination of anti-PD-1 antibody with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) [37,38], and first- and second-line treatment. The immune checkpoint-inhibiting anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies may prove useful for adjuvant therapy or combination therapy in all these settings. Immune checkpoint inhibitors could be particularly effective for the treatment of inflammation induced by TACE or radiofrequency ablation (RFA) [39,40], which releases highly antigenic neoantigens into the bloodstream. A clinical trial of adjuvant therapy with anti-CTLA-4 antibody after TACE and RFA is currently underway (table 9). The results of the interim analysis for that trial were presented at ASCO 2016. Adjuvant therapy with anti-CTLA-4 antibody after non-curative RFA or TACE caused an increase in CD3-positive and CD8-positive cells, even for untreated nodules [41].

Table 9.

Clinical trials of CTLA-4 antibody for the treatment of HCC

| NCT no. | Agent | Design | Status | n | Stage | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01008358 | Tremelimumab | II | Complete | 20 | III/IV | PR=17.6%, DCR=76% TTP=6.5 months HCV virologic response Grade 3 AST/ALT=45% |

| 01853618 | Tremelimumab + TACE/RFA/cryoablation | I | Ongoing | 29 14 TACE 10 RFA 5 Cryoablation | III/IV | Safe, feasible Immune cell infiltration (+) TTP=5.7 month Reduction in HCV viral load |

A most promising topic in this area is the combination of these antibodies (anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies) with other drugs. Potential drug combinations include anti-CTLA4 antibodies (ipilimumab and tremelimumab) and molecular targeted drugs (sorafenib and others). The combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab has yielded treatment outcomes superior to those of monotherapy with either drug in melanoma [31,42].

Rapid advances in the field of immunotherapy have been made in other types of cancer. The FDA designated nivolumab as a breakthrough therapy in September 2014, and later did the same for pembrolizumab. This raised hopes that anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies will be approved for the treatment of HCC in the near future. The outcomes of liver cancer treatment strategies are widely expected to improve through the application of multidrug and locoregional therapies centered on immune checkpoint inhibitors. The field is in the middle of a paradigm shift in not only systemic therapy, but also comprehensive treatment strategies, including locoregional therapy for liver cancer.

Conclusion

Having advanced through the first stage of chemotherapy centered on cytotoxic agents and the second stage of chemotherapy centered on molecular targeted therapies, we are now poised to enter a third stage of cancer treatment strategies centered on immune checkpoint inhibitors. These strategies promise to become an essential element in cancer treatment, and advances in this area will bring the paradigm shift in cancer treatment.

References

- 1.Ishida Y, Agata Y, Shibahara K, Honjo T. Induced expression of PD-1, a novel member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily, upon programmed cell death. EMBO J. 1992;11:3887–3895. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freeman GJ, Long AJ, Iwai Y, Bourque K, Chernova T, Nishimura H, Fitz LJ, Malenkovich N, Okazaki T, Byrne MC, Horton HF, Fouser L, Carter L, Ling V, Bowman MR, Carreno BM, Collins M, Wood CR, Honjo T. Engagement of the PD-1 immunoinhibitory receptor by a novel B7 family member leads to negative regulation of lymphocyte activation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1027–1034. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter L, Fouser LA, Jussif J, Fitz L, Deng B, Wood CR, Collins M, Honjo T, Freeman GJ, Carreno BM. PD-1:PD-L inhibitory pathway affects both CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cells and is overcome by IL-2. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:634–643. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200203)32:3<634::AID-IMMU634>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Latchman Y, Wood CR, Chernova T, Chaudhary D, Borde M, Chernova I, Iwai Y, Long AJ, Brown JA, Nunes R, Greenfield EA, Bourque K, Boussiotis VA, Carter LL, Carreno BM, Malenkovich N, Nishimura H, Okazaki T, Honjo T, Sharpe AH, Freeman GJ. PD-L2 is a second ligand for PD-1 and inhibits T cell activation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:261–268. doi: 10.1038/85330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okazaki T, Honjo T. PD-1 and PD-1 ligands: from discovery to clinical application. Int Immunol. 2007;19:813–824. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwai Y, Ishida M, Tanaka Y, Okazaki T, Honjo T, Minato N. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12293–12297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192461099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krummel MF, Allison JP. CD28 and CTLA-4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. J Exp Med. 1995;182:459–465. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271:1734–1736. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen DS, Mellman I. Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity. 2013;39:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sznol M, Chen L. Antagonist antibodies to PD-1 and B7-H1 (PD-L1) in the treatment of advanced human cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:1021–1034. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, Fine GD, Hamid O, Gordon MS, Sosman JA, McDermott DF, Powderly JD, Gettinger SN, Kohrt HE, Horn L, Lawrence DP, Rost S, Leabman M, Xiao Y, Mokatrin A, Koeppen H, Hegde PS, Mellman I, Chen DS, Hodi FS. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shih K, Arkenau HT, Infante JR. Clinical impact of checkpoint inhibitors as novel cancer therapies. Drugs. 2014;74:1993–2013. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0305-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philips GK, Atkins M. Therapeutic uses of anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies. Int Immunol. 2015;27:39–46. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxu095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahoney KM, Freeman GJ, McDermott DF. The next immune-checkpoint Inhibitors: PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in melanoma. Clin Ther. 2015;37:764–782. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harshman LC, Drake CG, Wargo JA, Sharma P, Bhardwaj N. Cancer immunotherapy highlights from the 2014 ASCO Meeting. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2:714–719. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Targeting the PD-1/B7-H1(PD-L1) pathway to activate anti-tumor immunity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:207–212. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merelli B, Massi D, Cattaneo L, Mandalà M. Targeting the PD1/PD-L1 axis in melanoma: biological rationale, clinical challenges and opportunities. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2014;89:140–165. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, Skora AD, Luber BS, Azad NS, Laheru D, Biedrzycki B, Donehower RC, Zaheer A, Fisher GA, Crocenzi TS, Lee JJ, Duffy SM, Goldberg RM, de la Chapelle A, Koshiji M, Bhaijee F, Huebner T, Hruban RH, Wood LD, Cuka N, Pardoll DM, Papadopoulos N, Kinzler KW, Zhou S, Cornish TC, Taube JM, Anders RA, Eshleman SR, Vogelstein B, Diaz LA., Jr PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Droeser RA, Hirt C, Viehl CT, Frey DM, Nebiker C, Huber X, Zlobec I, Eppenberger-Castori S, Tzankov A, Rosso R, Zuber M, Muraro MG, Amicarella F, Cremonesi E, Heberer M, Iezzi G, Lugli A, Terracciano L, Sconocchia G, Oertli D, Spagnoli GC, Tornillo L. Clinical impact of programmed cell death ligand 1 expression in colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2233–2242. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ribas A. Tumor immunotherapy directed at PD-1. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2517–2519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1205943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, Hodi FS, Hwu WJ, Kefford R, Wolchok JD, Hersey P, Joseph RW, Weber JS, Dronca R, Gangadhar TC, Patnaik A, Zarour H, Joshua AM, Gergich K, Elassaiss-Schaap J, Algazi A, Mateus C, Boasberg P, Tumeh PC, Chmielowski B, Ebbinghaus SW, Li XN, Kang SP, Ribas A. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brahmer JR, Tykodi SS, Chow LQ, Hwu WJ, Topalian SL, Hwu P, Drake CG, Camacho LH, Kauh J, Odunsi K, Pitot HC, Hamid O, Bhatia S, Martins R, Eaton K, Chen S, Salay TM, Alaparthy S, Grosso JF, Korman AJ, Parker SM, Agrawal S, Goldberg SM, Pardoll DM, Gupta A, Wigginton JM. Safety and activity of anti-PD-L1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao Q, Wang XY, Qiu SJ, Yamato I, Sho M, Nakajima Y, Zhou J, Li BZ, Shi YH, Xiao YS, Xu Y, Fan J. Overexpression of PD-L1 significantly associates with tumor aggressiveness and postoperative recurrence in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:971–979. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tochio H, Sugahara M, Imai Y, Tei H, Suginoshita Y, Imawsaki N, Sasaki I, Hamada M, Minowa K, Inokuma T, Kudo M. Hyperenhanced rim surrounding liver metastatic tumors in the postvascular phase of sonazoid-enhanced ultrasonography: a histological indication of the presence of Kupffer cells. Oncology. 2015;89(Suppl 2):33–41. doi: 10.1159/000440629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anthony B, El-Khoueiry IM, Todd S. Crocenzi, et al. Phase I/II safety and antitumor activity of nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): CA209-040. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33((suppl; abstr LBA101)) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kudo M. Immune checkpoint blockade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2015;4:201–207. doi: 10.1159/000367758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sangro B, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of nivolumab (nivo) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Interim analysis of dose-expansion cohorts from the phase 1/2 CheckMate-040 study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34((suppl; abstr 4078)) [Google Scholar]

- 29.El-Khoueiry AB, et al. Phase I/II safety and antitumor activity of nivolumab (nivo) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): Interim analysis of the CheckMate-040 dose escalation study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34((suppl; abstr 4012)) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sangro B, Gomez-Martin C, de la Mata M, Iñarrairaegui M, Garralda E, Barrera P, Riezu-Boj JI, Larrea E, Alfaro C, Sarobe P, Lasarte JJ, Pérez-Gracia JL, Melero I, Prieto J. A clinical trial of CTLA-4 blockade with tremelimumab in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2013;59:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Rizvi NA, Lesokhin AM, Segal NH, Ariyan CE, Gordon RA, Reed K, Burke MM, Caldwell A, Kronenberg SA, Agunwamba BU, Zhang X, Lowy I, Inzunza HD, Feely W, Horak CE, Hong Q, Korman AJ, Wigginton JM, Gupta A, Sznol M. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:122–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, Halwani A, Scott EC, Gutierrez M, Schuster SJ, Millenson MM, Cattry D, Freeman GJ, Rodig SJ, Chapuy B, Ligon AH, Zhu L, Grosso JF, Kim SY, Timmerman JM, Shipp MA, Armand P. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, Arance A, Grob JJ, Mortier L, Daud A, Carlino MS, McNeil C, Lotem M, Larkin J, Lorigan P, Neyns B, Blank CU, Hamid O, Mateus C, Shapira-Frommer R, Kosh M, Zhou H, Ibrahim N, Ebbinghaus S, Ribas A, KEYNOTE-006 investigators. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, Patnaik A, Aggarwal C, Gubens M, Horn L, Carcereny E, Ahn MJ, Felip E, Lee JS, Hellmann MD, Hamid O, Goldman JW, Soria JC, Dolled-Filhart M, Rutledge RZ, Zhang J, Lunceford JK, Rangwala R, Lubiniecki GM, Roach C, Emancipator K, Gandhi L, KEY-NOTE-001 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, Crinò L, Eberhardt WE, Poddubskaya E, Antonia S, Pluzanski A, Vokes EE, Holgado E, Waterhouse D, Ready N, Gainor J, Arén Frontera O, Havel L, Steins M, Garassino MC, Aerts JG, Domine M, Paz-Ares L, Reck M, Baudelet C, Harbison CT, Lestini B, Spigel DR. Nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced squamous-cell non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:123–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Schadendorf D, Dummer R, Smylie M, Rutkowski P, Ferrucci PF, Hill A, Wagstaff J, Carlino MS, Haanen JB, Maio M, Marquez-Rodas I, McArthur GA, Ascierto PA, Long GV, Callahan MK, Postow MA, Grossmann K, Sznol M, Dreno B, Bastholt L, Yang A, Rollin LM, Horak C, Hodi FS, Wolchok JD. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kudo M. Locoregional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2015;4:163–164. doi: 10.1159/000367741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsurusaki M, Murakami T. Surgical and locoregional therapy of HCC: TACE. Liver Cancer. 2015;4:165–175. doi: 10.1159/000367739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang TW, Rhim H. Recent advances in tumor ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2015;4:176–187. doi: 10.1159/000367740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lencioni R, de Baere T, Martin RC, Nutting CW, Narayanan G. Image-guided ablation of malignant liver tumors: recommendations for clinical validation of novel thermal and non-thermal technologies − a Western perspective. Liver Cancer. 2015;4:208–214. doi: 10.1159/000367747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duffy A, Makarova-Rusher OV, Pratt D, Kleiner DE, Ulahannan S, Mabry D, et al. Tremelimumab, a monoclonal antibody against CTLA-4, in combination with subtotal ablation (trans-catheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE), radiofrequency ablation (RFA) or cryoablation) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and biliary tract carcinoma (BTC). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34((suppl; abstr 4073).) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, Robert C, Grossmann K, McDermott D, Linette GP, Meyer N, Giguere JK, Agarwala SS, Shaheen M, Ernstoff MS, Minor D, Salama AK, Taylor M, Ott PA, Rollin LM, Horak C, Gagnier P, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2006–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]