Abstract

Ascaridomorph nematodes threaten the health of humans and other animals worldwide. Despite their medical, veterinary and economic importance, the identification of species lineages and establishing their phylogenetic relationships have proved difficult in some cases. Many working hypotheses regarding the phylogeny of ascaridomorphs have been based on single-locus data, most typically nuclear ribosomal RNA. Such single-locus hypotheses lack independent corroboration, and for nuclear rRNA typically lack resolution for deep relationships. As an alternative approach, we analyzed the mitochondrial (mt) genomes of anisakids (~14 kb) from different fish hosts in multiple countries, in combination with those of other ascaridomorphs available in the GenBank database. The circular mt genomes range from 13,948-14,019 bp in size and encode 12 protein-coding genes, 2 ribosomal RNAs and 22 transfer RNA genes. Our analysis showed that the Pseudoterranova decipiens complex consists of at least six cryptic species. In contrast, the hypothesis that Contracaecum ogmorhini represents a complex of cryptic species is not supported by mt genome data. Our analysis recovered several fundamental and uncontroversial ascaridomorph clades, including the monophyly of superfamilies and families, except for Ascaridiidae, which was consistent with the results based on nuclear rRNA analysis. In conclusion, mt genome analysis provided new insights into the phylogeny and taxonomy of ascaridomorph nematodes.

Parasitic nematodes (roundworms) cause diseases associated with serious morbidity and mortality in animals and substantial reductions in crop yields1. For example, species in the superfamily Ascaridoidea (ascaridoids)2, including species of Anisakis, Ascaris, Baylisascaris, Contracaecum, Pseudoterranova and Toxocara, are particularly important pathogens of various animals, and are transmissible to humans, where they cause diseases such as anisakidosis, ascariasis and toxocariasis3,4,5. In cases where ascaridoid larvae are directly responsible for human disease, infection is acquired through accidental ingestion of embryonated eggs (e.g., toxocariasis) or the consumption of larvae within raw meat or fish products (e.g., anisakidosis)6.

Although some species of ascaridoids can be readily identified and distinguished based on morphological features (e.g., Toxocara cati, Toxocara canis and Toxascaris leonina), molecular data have revealed cryptic species complexes within other morphological species (e.g., Anisakis simplex, Contracaecum rudolphii and Pseudoterranova decipiens). Some of these cryptic species show considerable differences in host and geographical ranges7,8,9. The biodiversity of ascaridoids is substantial, consistent with the broad range of hosts infected by these nematodes, including birds, mammals, reptiles, fish and amphibians10; there are also differences in ecology of particular host-parasite affiliations, and considerable genetic variation within species11. Important zoonotic disease complexes, such as anisakidosis, have substantial public health impact in several countries, including China, Germany, Japan, Netherlands and Spain12, emphasizing the need for improved diagnosis of the causative agents.

The accurate identification of ascaridoids to species is central to diagnosis, and also underpins fundamental and applied research of these important parasites. Challenges to diagnosis include the lack of species-level morphological features for most larvae, which are the stage responsible for disease in many cases. For many ascaridoid species complexes, identification to species is not possible based on morphology, such that nuclear or mitochondrial (mt) markers are necessary for identification. The first and second internal transcribed spacers of nuclear ribosomal DNA (ITS-1 and ITS-2 = ITS) have frequently been used as a species-specific marker in such cases13,14,15,16. By contrast, because of its relative conservation, the small subunit (SSU) of nuclear ribosomal RNA gene does not consistently provide sufficient sequence variation for the differentiation of ascaridoid species17. Most mt genes are much more variable in sequence than nuclear ribosomal RNA genes18,19, and recent studies have shown that amino acid sequences inferred from mt genome sequences are very useful for species identification as well as for investigating their inter-relationships20,21,22,23,24.

Detailed studies by Nadler et al.25,26, investigated the phylogenetic relationships of a range of Ascaridomorph taxa. Despite these advances, difficulties remain concerning the detection of cryptic species and the relationships among major lineages, such as families and superfamilies. For example, although some studies27,28 indicated that Anisakidae is more closely related to Ascarididae than to Toxocaridae, others29,30 have argued the opposite, and some have suggested that Anisakidae is sister to Toxocaridae + Ascarididae31,33. These results reflect inadequate resolution at higher levels for nuclear ribosomal data, conflicts between different inference methods, impacts of taxon sampling and limited phylogenetic signal from small data sets34,35. To overcome these limitations, we employed complete amino acid sequence data sets derived from mt genomes. Herein, we sequenced the complete mt genomes of six anisakids (Table 1), and reconstructed phylogenetic relationships using the data of these anisakids in combination with all mt genomic data sets available for ascaridomorph nematodes in public databases. Analyses of mt genome sequences in the present study have provided novel insights into the phylogenetic relationships of several major lineages of ascaridomorphs.

Table 1. Anisakid nematodes representing Pseudoterranova spp. and Contracaecum ogmorhini populations from different hosts, geographical origins and GenBank accession numbers.

| Species/population | Host species | Geographical origin | Mitochondrial genome Accession no | ITS-2 Accession no |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudoterranova bulbosa | Erignathus barbatus (Bearded seal) | Newfoundland, Canada | KU558720 | AJ413971 |

| Pseudoterranova cattani | Otaria byronia (South American sea lion) | Concepcion, Chile | KU558721 | AJ413983 |

| Pseudoterranova decipiens s.l. | Chaenocephalus aceratus (Blackfin icefish) | South Shetland Islands, Antarctica | KU558722 | AJ413980 |

| Pseudoterranova decipiens s.l. | Osmerus eperlanus (European smelt) | Elbe estuary, Germany | KU558723 | AJ413978 |

| Pseudoterranova krabbei | Halichoerus grypus (Grey seal) | Froya Island, Norway | KU558724 | AJ413966 |

| Contracaecum ogmorhini s.l. | Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus | Australia | KU558725 | AJ291473 |

| Contracaecum ogmorhini s.l. | Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus | South Africa | KU558726 | AJ291472 |

| Contracaecum ogmorhini s.l. | Zalophus californianus | Pacific Canada | KU558727 | AJ291471 |

Results

Mitochondrial genomes of selected anisakids

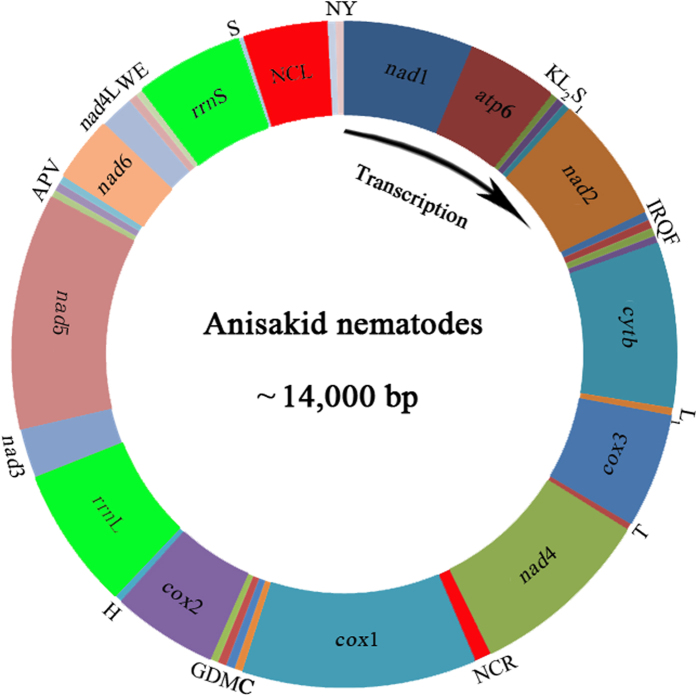

The complete mt genomes of Pseudoterranova krabbei, Pseudoterranova decipiens s.l. (host Chaenocephalus aceratus) (PDCA), Pseudoterranova decipiens s.l. (host Osmerus eperlanus) (PDOE), Pseudoterranova cattani, Pseudoterranova bulbosa and three Contracaecum ogmorhini s.l. from different hosts [Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus (COAPD), Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus (COAPP) and Zalophus californianus (COZC)] were 13,948 bp, 13,965 bp, 13,962 bp, 13,950 bp, 13,957 bp, 14,019 bp, 14,013 bp and 14,010 bp, respectively. Each of the 8 mt genomes contains 36 genes, consisting of 12 protein-encoding, 2 rRNA, and 22 tRNA genes (Fig. 1), which is typical for chromadorean nematodes. Gene order (36 genes) for eight genomes is the same as published for Anisakis simplex (Anisakidae)32, Ascaris spp. (Ascarididae)36 Toxocara spp. (Toxocaridae)31, but distinct from Ascaridia spp. (Ascaridiidae)20 and Cucullanus robustus (Cucullanidae)34. In comparison to the Ascaridia species, at least three rearrangement events occurred in An. simplex. The 12 protein-coding genes have ATT, ATG or TTG as a start codon. Most of the protein-coding genes use TAA or TAG as a complete termination codon, except for cox1, cox2, cox3, nad5 and nad4L, which have abbreviated stop codons (TA or T). The tRNA genes range from 52 to 63 bp. Their predicted secondary structures (not shown) are similar to those of other anisakids24,32,37,38. The rrnL gene is located between tRNA-His and nad3, and rrnS gene is located between tRNA-Glu and tRNA-SerUCN. The longer non-coding region (NCL) is located between the tRNA-SerUCN and tRNA-Asn, and the shorter non-coding region (NCR) is between nad4 and cox1.

Figure 1. The mitochondrial genomes representing six anisakid nematodes.

All genes are on the same DNA strand and are transcribed clockwise. Protein-coding and rRNA genes are indicated with the standard nomenclature. tRNA genes are indicated with the one-letter code of their corresponding amino acids. There are two tRNA genes for leucine: L1 for codons CUN and L2 for UUR; and two tRNA genes for serine: S1 for codons AGN and S2 for UCN. “NCL” refers to the large non-coding region. “NCR” refers to a small non-coding region.

Comparative analyses of members of the P. decipiens complex and C. ogmorhini

Nucleotide sequences or the conceptually translated amino acid sequences from the protein-coding genes were aligned and compared to assess sequence divergence. Across the entire mt genome, the uncorrected nucleotide sequence divergence was 3.8–9.4% among members of the P. decipiens species complex. For the same group of species, the divergence across nucleotide and amino acid sequences for all protein-coding genes was 3.7–10.6% and 1.7–9.1%, respectively. A comparison of the nucleotide and amino acid divergence between C. ogmorhini from three different host species is provided in Table 2. Across the entire mt genome, the sequence divergence between COAPD and COAPP was 0.6% (93 nucleotide substitutions), 1.7% (244 nucleotide substitutions) between COAPP and COZC, and 1.7% (243 nucleotide substitutions) between COAPD and COZC. For the protein-coding genes, the respective divergences in nucleotide and amino acid sequences were 0.6% and 0.9% between COAPD and COAPP; 1.8% and 1.1% between COAPP and COZC; and 1.8% and 1.0% between COAPD and COZC, respectively.

Table 2. Nucleotide (nt) and/or predicted amino acid (aa) sequence differences in each mt gene among three Contracaecum ogmorhini samples upon pairwise comparison.

| Gene/region | Nt sequence length | COZC | Nt difference (%) | Number of aa | COZC | aa difference (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COAPD | COAPP | COAPD/COAPP | COAPP/COZC | COAPP/COZC | COAPD | COAPP | COAPD/COAPP | COAPP/COZC | COAPP/COZC | |||

| atp6 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 199 | 199 | 199 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0 |

| nad1 | 873 | 873 | 873 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 290 | 290 | 290 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| nad2 | 846 | 846 | 846 | 0.7 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 281 | 281 | 281 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| nad3 | 336 | 336 | 336 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 111 | 111 | 111 | 0 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| nad4 | 1230 | 1230 | 1230 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 409 | 409 | 409 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.7 |

| nad4L | 234 | 234 | 234 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 77 | 77 | 77 | 0 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| nad5 | 1582 | 1579 | 1582 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 527 | 526 | 527 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| nad6 | 435 | 435 | 434 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 144 | 144 | 144 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| cox1 | 1576 | 1576 | 1576 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 525 | 525 | 525 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| cox2 | 696 | 696 | 696 | 0.4 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 231 | 231 | 231 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| cox3 | 766 | 766 | 766 | 0.4 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 152 | 152 | 152 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| cytb | 1107 | 1107 | 1107 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 368 | 368 | 368 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.5 |

| rrnS | 691 | 690 | 690 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.9 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| rrnL | 963 | 962 | 962 | 0.6 | 2.1 | 1.9 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 22 tRNAs | 1253 | 1243 | 1254 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.5 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

COAPD: Contracaecum ogmorhini s.l. (Arctocephalus pusillus doriferus).

COAPP: Contracaecum ogmorhini s.l. (Arctocephalus pusillus pusillus).

COZC: Contracaecum ogmorhini s.l. (Zalophus californianus).

Phylogeny of ascaridoids inferred from mt genomic data sets

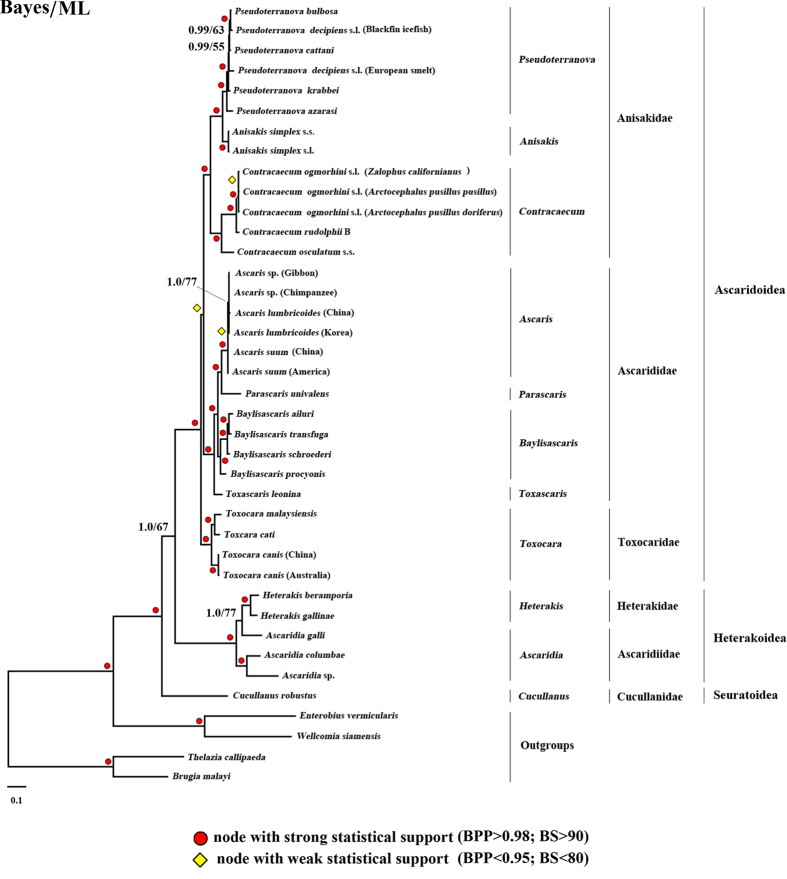

The 35 mt genomes analyzed include 20 species (29 taxa) representing Ascaridoidea, 4 species (5 taxa) of Heterakoidea and one species of Seuratoidea (Supplementary Table S1). Monophyly of the superfamilies Ascaridoidea (including three families Ascarididae, Toxocaridae and Anisakidae) and Heterakoidea (including two families Heterakidae and Ascaridiidae) were strongly supported in Bayesian (posterior probability, BPP = 1.0, Fig. 2) and maximum likelihood (ML) (bootstrap, BS = 100%, Fig. 2) analyses.

Figure 2. Phylogenetic relationships among ascaridoid nematodes inferred from Bayesian and maximum likelihood analyses of amino acid sequences for 12 mitochondrial genes.

Thelazia callipaeda, Brugia malayi, Wellcomia siamensis and Enterobius vermicularis were used as outgroups. Bayesian posterior probability (BPP) and maximum likelihood bootstrap proportions (BS) are shown.

The Ascaridoidea, represented by families Ascarididae, Toxocaridae and Anisakidae, were monophyletic, with strong nodal support in Bayesian and ML analyses (BPP = 1.0, BS = 100%, Fig. 2). The family Ascarididae was monophyletic, with strong support in all analyses (BPP = 1.0, BS = 100%), as was the family Toxocaridae (BPP = 1.0, BS = 100%) and the family Anisakidae (BPP = 1.0, BS = 98%) (Fig. 2). Although there is strong support for monophyly of the Ascaridoidea (Anisakidae, Ascarididae, Toxocaridae), support for the sister-group relationship (Toxocaridae, (Anisakidae, Ascarididae)) differed greatly between the Bayesian and ML methods (BPP = 0.97, BS = 55%). The superfamily Heterakoidea was represented by five species from the families Heterakidae and Ascaridiidae, and was strongly supported as monophyletic (BPP = 1.0, BS = 100%, Fig. 2). The two species representing the Heterakidae were monophyletic, with strong support (BPP = 1.0, BS = 100%) in both analyses, but the three representatives of the family Ascaridiidae (all species of Ascaridia) were paraphyletic. One species of Ascaridia, A. galli, was sister to the two Heterakis species, whereas the remaining two Ascaridia taxa grouped together. The close relationship of A. galli to the two Heterakis species was strongly supported by Bayesian inference, but weakly supported in the ML analysis. Eight of the 11 in-group genera analyzed has two or more representative species (Fig. 2); all of these genera, except Ascaridia, were monophyletic, with strong BPP or BS support.

Within the family Ascarididae, the genus Toxascaris (represented by T. leonina) was sister to Baylisascaris spp., Parascaris univalens and Ascaris spp. (Fig. 2, BPP = 1.0, BS = 100%), supporting the genus Toxascaris as a member of the Ascarididae. In addition, P. univalens was sister to the genus Ascaris (represented by A. lumbricoides and A. suum) (Fig. 2, BPP = 1.0, BS = 99%), whereas four species of the genus Baylisascaris were a sister group to Ascaris plus Parascaris (Fig. 2, BPP = 1.0, BS = 100%). The genus Toxocara (represented by three species) was sister to the seven genera representing the Ascarididae plus Anisakidae. Within the family Anisakidae, Pseudoterranova (five species) was strongly supported as being sister to the genus Anisakis (Fig. 2, BPP = 1.0, BS = 100%), and Contracaecum (three species) was sister to Anisakis plus Pseudoterranova (Fig. 2, BPP = 1.0, BS = 98%).

Discussion

Ascaridomorph nematodes are diverse; the superfamily Ascaridoidea alone contains more than 50 genera, including parasites of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fishes. Most molecular phylogenetic studies have focused on ascaridoid genera in the families Ascarididae and Anisakidae, and have mainly been based on nuclear ribosomal RNA genes25,26,27,28. More recently, some phylogenetic studies of the Ascaridida have used mt genetic7,39 and complete mt genomic data sets29,32,34,35. Here, we sequenced the mt genomes of eight representatives of the family Anisakidae and conducted comprehensive phylogenetic analyses of these nematodes and all other ascaridomorphs for which mt genomic data were available in databases. The present study has reinforced insights into the phylogenetic relationships of several lineages of ascaridomorphs and delivers a rich source of genetic markers for systematic, population genetic and epidemiological studies of these nematodes. In addition, such markers might also be used to explore the host specificity and zoonotic potential of these worms.

Our results are consistent with the division of the sampled ascaridomorph nematodes into three superfamilies: Ascaridoidea, Heterakoidea and Seuratoidea. Each of these superfamilies was monophyletic in our analysis with strong support, regardless of the analytical method. Within the superfamily Ascaridoidea, monophyly of the families Ascarididae, Anisakidae and Toxocaridae are each strongly supported by Bayesian and ML analyses. The best Bayesian consensus tree depicts a sister group relationship between Anisakidae and Ascarididae; however, this relationship is not reliably supported by ML bootstrap resampling. In other analyses of mt genomes, phylogenetic trees support a closer relationship between Anisakidae and Toxocaridae29,34, but these studies involved single representatives of each family. Analysis of nuclear SSU rRNA sequence data supports a closer relationship between Ascarididae and Toxocaridae26. In other analyses of molecular data, Anisakidae is sister to Ascarididae plus Toxocaridae31,32,33. Given the conflicts between these different analyses and datasets, it seems that additional loci will be required to resolve the sister-group relationships among the Anisakidae, Toxocaridae and Ascarididae.

Within the Ascarididae and Anisakidae, the relationships among genera based on mt genome sequence data is the same as that from a combined analysis of nuclear rRNA gene and cox2 as well as morphological data sets39. Relationships of species groups within Contracaecum are also consistent with the results inferred from nuclear rRNA gene sequences40.

The present study included five species from the superfamily Heterakoidea, two from the family Heterakidae and three from the family Ascaridiidae. In a previous investigation of mt genomes, monophyly of Ascaridiidae was well supported based on phylogenetic analysis of Ascaridia species20; however, inclusion of Heterakis species yields a non-monophyletic Ascardiidae due to the sister-group relationship of A. galli to Heterakis. Support for this result was strong from Bayesian inference (BPP = 1.0), but weak from ML analysis (BS = 77%). Some previous studies using morphological data indicated that the families Heterakidae and Ascaridiidae (Heterakoidea) were most closely related to the infra-order Oxyuridomorpha41. However, studies based on SSU rRNA gene sequence data have yielded conflicting results. For example, approximately half of the analyses performed by Nadler et al.26, based on SSU rRNA, yield a sister group relationship between Oxyuridomorpha and Heterakoidea. Previous studies of mt genomic data sets including those of Ascaridia32, Heterakis42 and Ascaridia20 supported a close relationship between Ascaridiidae and Ascaridomorpha. The improved sampling of Heterakoidea analyzed herein also supports a clade consisting of Ascaridoidea and Heterakoidea, rather than Heterakoidea and Oxyuridomorpha. Consistent with previous studies20,32,43, the current study provides strong support that Ascaridia galli is sister to the genus Heterakis, and supports the hypothesis that families Heterakidae and Ascaridiidae are more closely related to the infra-order Ascaridomorpha.

There is considerable value in employing mt genome markers to explore genetic variation within the genera Pseudoterranova and C. ogmorhini, because phenotypic differentiation is unreliable44. The P. decipiens complex consists of at least five cryptic species (genetically but morphologically indistinguishable), namely P. decipiens, P. azarasi, P. cattani, P. krabbei and P. bulbosa45,46. From the present study, nucleotide and amino acid sequences representing the mt proteome show a range of divergences (3.7–10.6% and 1.7–9.1%, respectively), and phylogenetic analyses indicate that these Pseudoterranova samples represent six distinct lineages (cf. Fig. 2). The nucleotide sequence differentiation (3.8–9.4%) detected in mt genomes was consistent with previous findings of differentiation (0–6.8%) in the sequences of the nuclear ITS rDNA from five P. decipiens species complex members47. In addition, we characterized here the mt genomes of three representatives of C. ogmorhini from different origins and hosts, and found sequence differences of <1.8% in the genes representing the mt proteome, which is comparable with levels detected between A. suum specimens from China and USA (1.5%)36, and T. canis from China and Australia (2.3%)31,48 (cf. Fig. 2). Taken together, these findings suggest that C. ogmorhini specimens from different host species represent a single species rather than sibling species, which contradicts previous conclusions from studies using nuclear ITS rDNA showing limited nucleotide variation (0.2–0.7%)49.

Methods

Genomic DNA samples of anisakid nematodes

Genomic DNA samples representing five sibling species of the Pseudoterranova decipiens complex and three populations of C. ogmorhini s.l. are listed in Table 1. These DNA samples had been used in our two previous studies47,49, and these anisakids had been identified preliminarily to species based on host preference, morphological characters and predilection sites50. The identities of these DNA samples were re-confirmed by PCR amplification and sequencing of the region spanning ITS-1, 5.8 S rRNA gene and ITS-247,49. In addition, phylogenetic analysis of ITS data supports clustering of the Pseudoterranova in a previous study49.

PCR amplification of the mt genomes of Anisakid nematodes

Based on the published mt genome sequences of anisakids23,32,38, we designed specific primers for long PCR amplification (Supplementary Table S2). We amplified the entire mt genome of individual specimens of anisakid nematodes by long PCR in four or five overlapping fragments, respectively. The four overlapping long-PCR fragments for P. krabbei, P. bulbosa, P. cattani and P. decipiens s.l. (Blackfin icefish) were between nad1 and nad4 (~5.0 kb), between nad4 and rrnL (~4.5 kb), between rrnL and rrnS (~3.5 kb) and between rrnS and nad1 (~2.0 kb). The five overlapping long-PCR fragments for P. decipiens s.l. (European smelt) were: nad1 to cytb (~3.0 kb), cytb to nad4 (~2.5 kb), nad4 to cox1 (~1.5 kb), cox1 to rrnL (~3.0 kb), and rrnL to nad1 (~5.0 kb) (cf. Fig. 1). The five overlapping long-PCR fragments for C. ogmorhini from different hosts were: nad1 to cox3 (~4.0 kb), cox3 to cox1 (~3.0 kb), cox1 to rrnL (~3.0 kb), rrnL to rrnS (~4.0 kb) and rrnS to nad1 (~1.8 kb). Each long-PCR reaction was performed in 25 μl using 2 mM MgCl2, 4.0 μL 0.2 mM each of dNTPs, 2.5 μL 10× rTaq buffer, 0.25 μL 2.5 μM of each primer, 0.25 μL 1.25 U rTaq polymerase (Takara), and 20–50 ng of total genomic DNA. The PCR conditions were: 92 °C for 2 min (initial denaturation), then 92 °C for 10 sec (denaturation), 54–59 °C for 30 sec (annealing) and 60 °C for 4–5 min (extension) for five cycles, followed by 92 °C for 2 min, then 92 °C for 10 sec, 54–59 °C for 30 sec, and 66 °C for 4–5 min for 30 cycles, and a final extension at 68 °C for 10 min. PCR amplicons were column-purified and then sequenced using a primer-walking strategy51.

Sequence assembly and mt genome annotation

Sequence reads of anisakid nematodes were assembled with the program ContigExpress of the Vector NTI software package v.6.0 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The mt genome sequences of anisakid nematodes were aligned with those of other anisakid nematodes available from the GenBank database23,32,38 using Clustal X 1.8352 to infer gene boundaries. Sequences of protein-coding genes were translated into amino acid sequences using the invertebrate mt genetic code in MEGA 5.053. Translation initiation and termination codons were identified by comparison with those of the anisakid nematodes reported previously23,32,38. The secondary structures of 22 tRNA genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE54, with manual adjustment55. Tandem repeats in the non-coding regions were found using Tandem Repeat Finder program (http://tandem.bu.edu/trf/trf.html)56.

Phylogenetic analyses

All mt genome sequences of the infra-order Ascaridomorpha, along with those of selected Chromadorea outgroups, were obtained from GenBank and combined for phylogenetic analysis; Thelazia callipaeda, Brugia malayi, Wellcomia siamensis and Enterobius vermicularis were used to root the trees. Amino acid sequences inferred from the nucleotide sequences of 12 mt protein-coding genes were aligned individually using MAFFT v.7.12257 and were then concatenated to form a single dataset; ambiguously aligned regions were excluded using Gblocks 0.91b58 using default parameters.

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using Bayesian (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) inference. Maximum likelihood analysis was performed using RAxML v.7.0.359 and implemented using the CIPRES web portal60. For ML analysis, the JTT (genes 1–8; cytb, cox1, cox3, atp6, nad2, nad3, nad4L and nad5), LG (genes 9–10; cox2 and nad1), and MtArt (genes 11–12; nad4 and nad6) models were used as selected by ProtTest 2.461 based on the Akaike information criterion (AIC). ML analysis was partitioned by gene, and bootstrap resampling was performed using the rapid bootstrapping option with 1,000 iterations. Bayesian analysis was also implemented using CIPRES and MrBayes 3.2.662, and four independent Markov chains were run for 100,000 metropolis-coupled MCMC generations, sampling trees every 100 generations. The first 250 trees represented burn-in, and the remaining trees were used to produce Bayesian consensus trees. The analysis was performed until the potential scale reduction factor approached 1 and the average standard deviation of split frequencies was <0.01. For Bayesian analysis, the dataset was partitioned by gene, and the amino acid (aa) model for each gene was estimated from a mixture of models with fixed rate matrices and gamma distributed rates. With this analysis, each model contributes to the results in proportion to its posterior probability (BPP). Maximum-likelihood bootstrap (BS) support of >70% was considered strong support63. Phylograms were drawn using FigTree v.1.31 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, G.-H. et al. Mitochondrial Phylogenomics yields Strongly Supported Hypotheses for Ascaridomorph Nematodes. Sci. Rep. 6, 39248; doi: 10.1038/srep39248 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31502052), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2016T90159), the International Science & Technology Cooperation Program of China (Grant No. 2013DFA31840) as well as the Australian Research Council (ARC) (R.B.G.). It was also supported by a Victorian Life Sciences Computation Initiative (VLSCI) grant (VR0007; R.B.G.) on its Peak Computing Facility at the University of Melbourne, an initiative of the Victorian Government. Other support from the University of Melbourne (BIP), the Australian Academy of Science, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Melbourne Water Corporation is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Author Contributions X.Q.Z., R.B.G. and G.H.L. designed the research. G.H.L. and S.S.L. performed the research. M.P. and S.D. contributed reagents/materials/analyses. G.H.L. and S.A.N. analyzed the data. G.H.L., S.A.N., R.B.G., R.S. and X.Q.Z. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Blaxter M. L. Nematoda: genes, genomes and the evolution of parasitism. Adv Parasitol. 54, 101–195 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R. C. Nematode Parasites of Vertebrates: Their Development and Transmission (ed Anderson R. C.). Ch. 5, 245–348 (CAB International, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins E. J. et al. Tradition and transition: parasitic zoonoses of people and animals in Alaska, northern Canada, and Greenland. Adv Parasitol. 82, 33–204 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. et al. Canine and feline parasitic zoonoses in China. Parasit Vectors. 5, 152 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsi S. Recent advances in our knowledge of Australian anisakid nematodes. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 3, 178–187 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell D. G. et al. Food-borne diseases - the challenges of 20 years ago still persist while new ones continue to emerge. Int J Food Microbiol. 139, S3–15 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiucci S. et al. Genetic and morphological approaches distinguish the three sibling species of the Anisakis simplex species complex, with a species designation as Anisakis berlandi n. sp. for A. simplex sp. C (Nematoda: Anisakidae). J Parasitol. 100, 199–214 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsi S. et al. Genetic and morphological evidences for the existence of sibling species within Contracaecum rudolphii (Hartwich, 1964) (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in Australia. Parasitol Res. 105, 529–538 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timi J. T. et al. Molecular identification, morphological characterization and new insights into the ecology of larval Pseudoterranova cattani in fishes from the Argentine coast with its differentiation from the Antarctic species, P. decipiens sp. E (Nematoda: Anisakidae). Vet Parasitol. 199, 59–72 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprent J. F. Ascaridoid nematodes of South American mammals, with a definition of a new genus. J Helminthol. 56, 275–295 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiucci S. & Nascetti G. Advances and trends in the molecular systematics of anisakid nematodes, with implications for their evolutionary ecology and host-parasite co-evolutionary processes. Adv Parasitol. 66, 47–148 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baird F. J. et al. Foodborne anisakiasis and allergy. Mol Cell Probes. 28, 167–174 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. W. et al. The occurrence of Toxocara malaysiensis in cats in China, confirmed by sequence-based analyses of ribosomal DNA. Parasitol Res. 99, 554–557 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X. Q. & Gasser R. B. Single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP)-based mutation scanning approaches to fingerprint sequence variation in ribosomal DNA of ascaridoid nematodes. Electrophoresis. 19, 1366–1373 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X. Q. et al. Molecular characterization of a Toxocara variant from cats in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Parasitology. 117, 64 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X. et al. Characterisation of Ascaris from human and pig hosts by nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences. Int J Parasitol. 29, 469–478 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler S. A. Phylogeny of some ascaridoid nematodes, inferred from comparison of 18S and 28S rRNA sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 9, 932–944 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. W. et al. Electrophoretic analysis of sequence variability in three mitochondrial DNA regions for ascaridoid parasites of human and animal health significance. Electrophoresis. 29, 2912–2917 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikaeili F. et al. Sequence variation in mitochondrial cox1 and nad1 genes of ascaridoid nematodes in cats and dogs from Iran. J Helminthol. 89, 496–501 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G. H. et al. The complete mitochondrial genomes of three parasitic nematodes of birds: a unique gene order and insights into nematode phylogeny. BMC Genomics. 14, 414 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G. H. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of Toxascaris leonina: comparison with other closely related species and phylogenetic implications. Infect Genet Evol. 21, 329–333 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y. et al. The mitochondrial genome of Baylisascaris procyonis. PLoS One. 6, e27066 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohandas N. et al. Mitochondrial genomes of Anisakis simplex and Contracaecum osculatum (sensu stricto)–comparisons with selected nematodes. Infect Genet Evol. 21, 452–462 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar A. et al. The mitochondrial genome of Parascaris univalens–implications for a “forgotten” parasite. Parasit Vectors. 7, 428 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler S. A. & Hudspeth D. S. Ribosomal DNA and phylogeny of the Ascaridoidea (Nemata: Secernentea): implications for morphological evolution and classification. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 10, 221–236 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler S. A. et al. Molecular phylogeny of clade III nematodes reveals multiple origins of tissue parasitism. Parasitology. 134, 1421–1442 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M. L. et al. A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda. Nature. 392, 71–75 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldal B. H. et al. An improved molecular phylogeny of the Nematoda with special emphasis on marine taxa. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 42, 622–636 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang S. et al. The mitochondrial genome sequence of Enterobius vermicularis (Nematoda: Oxyurida)–an idiosyncratic gene order and phylogenetic information for chromadorean nematodes. Gene. 429, 87–97 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. L. et al. Molecular phylogeny of slug-parasitic nematodes inferred from 18S rRNA gene sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 55, 738–743 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. W. et al. The complete mitochondrial genomes for three Toxocara species of human and animal health significance. BMC Genomics. 9, 224 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. et al. Phylogeny of Rhigonematomorpha based on the complete mitochondrial genome of Rhigonema thysanophora (Nematoda: Chromadorea). Zool Scr. 43, 289–303 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Liu G. H. et al. Gnathostoma spinigerum mitochondrial genome sequence: a novel gene arrangement and its phylogenetic position within the class Chromadorea. Sci Rep. 5, 12691 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J. K. et al. Monophyly of clade III nematodes is not supported by phylogenetic analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences. BMC Genomics. 12, 392 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana T. et al. Comparative analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequences confirms independent origins of plant-parasitic nematodes. BMC Evol Biol. 13, 12 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G. H. et al. Comparative analyses of the complete mitochondrial genomes of Ascaris lumbricoides and Ascaris suum from humans and pigs. Gene. 492, 110–116 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R. Q. et al. Contracaecum rudolphii B: gene content, arrangement and composition of its complete mitochondrial genome compared with Anisakis simplex s.l. Exp Parasitol. 130, 135–140 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S. S. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of Pseudoterranova azarasi and comparative analysis with other anisakid nematodes. Infect Genet Evol. 33, 293–298 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler S. A. & Hudspeth D. S. Phylogeny of the Ascaridoidea (Nematoda: Ascaridida) based on three genes and morphology: hypotheses of structural and sequence evolution. J Parasitol. 86, 380–393 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler S. A. et al. Phylogenetic relationships among species of Contracaecum Railliet & Henry, 1912 and Phocascaris Høst, 1932 (Nematoda:Ascaridoidea) based on nuclear rDNA sequence data. Parasitology. 121, 455–463 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Špakulová M. & Birová V. Efficacy of the per-rectal transfer of postinvasive Heterakis spumosa developmental stages (Nematoda: Oxyurata). Helminthologia. 27, 125–133 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Wang B. J. et al. Mitochondrial genomes of Heterakis gallinae and Heterakis beramporia support that they belong to the infraorder Ascaridomorpha. Infect Genet Evol. 40, 228–235 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šnábel V. et al. Molecular identification of Heterakis spumosa obtained from brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) in Japan and its infectivity in experimental mice. Parasitol Res. 113, 3449–3455 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Orts J. S. et al. Description, microhabitat selection and infection patterns of sealworm larvae (Pseudoterranova decipiens species complex, nematoda: ascaridoidea) in fishes from Patagonia, Argentina. Parasit Vectors. 29, 252 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paggi L. et al. Genetic evidence for three species within Pseudoterranova decipiens (Nematoda, Ascaridida, Ascaridoidea) in the north Atlantic and Norwegian and Barents Seas. Int J Parasitol. 21, 195–212 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paggi L. et al. Pseudoterranova decipiens species A and B (Nematoda, Ascaridoidea): nomenclatural designation, morphological diagnostic characters and genetic markers. Syst Parasitol. 45, 185–197 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X. Q. et al. SSCP-based identification of members within the Pseudoterranova decipiens complex (Nematoda: Ascaridoidea: Anisakidae) using genetic markers in the internal transcribed spacers of ribosomal DNA. Parasitology. 124, 615–623 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jex A. R. et al. The mitochondrial genome of Toxocara canis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2, e273 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X. et al. Electrophoretic detection of population variation within Contracaecum ogmorhini (Nematoda: Ascaridoidea: Anisakidae). Electrophoresis. 22, 1930–1934 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattiucci S. et al. Allozyme and morphological identification of Anisakis, Contracaecum and Pseudoterranova from Japanese waters (Nematoda, Ascaridoidea). Syst Parasitol. 40, 81–92 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Hu M. et al. Long PCR amplification of the entire mitochondrial genome from individual helminths for direct sequencing. Nat Protoc. 10, 2339–2344 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D. et al. The Clustal X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K. et al. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 28, 2731–2739 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe T. M. & Eddy S. R. tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M., Chilton N. B. & Gasser R. B. The mitochondrial genomes of the human hookworms, Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus (Nematoda: Secernentea). Int J Parasitol. 32, 145–158 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 573–580 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K. & Standley D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talavera G. & Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 56, 564–577 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 30, 1312–1313 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. A. Pfeiffer W. & Schwartz T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. In: Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), New Orleans, LA, USA, pp 1–8 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Abascal F., Zardoya R. & Posada D. ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 21, 2104–2105 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F. & Huelsenbeck J. P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 19, 1572–1574 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox T. P. et al. Phylogenetic relationships of the dwarf boas and a comparison of Bayesian and bootstrap measures of phylogenetic support. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 25, 361–371 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.