Abstract

Concatenation by covalent linkage of two protomers of an intertwined all-helical HP0242 homodimer from Helicobacter pylori results in the first example of an engineered knotted protein. While concatenation does not affect the native structure according to X-ray crystallography, the folding kinetics is substantially slower compared to the parent homodimer. Using NMR hydrogen-deuterium exchange analysis, we showed here that concatenation destabilises significantly the knotted structure in solution, with some regions close to the covalent linkage being destabilised by as much as 5 kcal mol−1. Structural mapping of chemical shift perturbations induced by concatenation revealed a pattern that is similar to the effect induced by concentrated chaotrophic agent. Our results suggested that the design strategy of protein knotting by concatenation may be thermodynamically unfavourable due to covalent constrains imposed on the flexible fraying ends of the template structure, leading to rugged free energy landscape with increased propensity to form off-pathway folding intermediates.

Recent surveys of the Protein Data Bank have identified hundreds of toplogically knotted protein structures, accounting for nearly 1% of the total entries1,2. The knotted topologies range from the simplest trefoil (31) knot, figure of eight (41) knot, Gordian (52) knot, to the most complex Stevedore’s (61) knot3. Many knotted proteins exhibit well-characterised enzymatic functions involved in RNA methyl transfer, transcarbamylation, ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolysis, or dehalogenation4. Jackson and co-workers have elucidated extensively the folding pathways of two trefoil knotted bacterial methyl transferases, YibK from Haemophilus influenzae and YbeA from Escherichia coli5,6,7. Remarkably, YibK and YbeA remain knotted in the presence of concentrated chaotrophic agents, despite the lack of appreciable secondary and tertiary structures8,9,10. In fact, both proteins are random coil-like under chemically denatured states according to small angle X-ray scattering analyses11. Using a reconstituted in vitro transcription/translation system, it was recently demonstrated that YibK and YbeA can knot themselves spontaneously during de novo folding immediately upon completion of protein synthesis, while molecular crowding through encapsulation by the chaperonin system accelerates significantly the folding and knotting processes12. Since then, efforts have been made to characterize experimentally the folding dynamics and kinetics of knotted proteins with different degrees of complexities, including the smallest trefoil knot, MJ036613, the most complex Stevedore’s knot, DehI14, and a family of Gordian knotted human ubiqtuitin C-terminal hydrolyases15,16,17. An emerging feature shared by all experimentally characterized knotted proteins is the presence of well-defined folding intermediate(s) along their folding pathways. This is consistent with theoretical predictions that knotting is the rate-limiting step along the multi-stage folding processes for most knotted proteins18,19,20,21,22,23.

In addition to naturally occurring knotted proteins, Yeates and co-workers reported the first example of a designed protein knot by concatenating an all-helical HP0242 from Helicobacter pylori that exists as an intertwined homodimer; the crystal structure of the concatenated variant is essentially identical to that of its parent with the flexible linker being too flexible to be defined in the crystal structure24,25. We have recently established the folding pathways of wild-type (wt) HP0242 and its concatenated form through multi-parametric spectroscopic analyses of the folding equilibria and kinetics induced by chemical denaturation26. HP0242 variants exhibit complex folding pathways with highly populated off-pathway folding intermediates that require back-tracking to attain native states, in line with theoretical predications19,27. To further examine in detail the folding of HP0242 variants and the impact of concatenation, we report here detailed folding analyses of HP0242 variants at atomic resolution by solution state NMR spectroscopy. Our results indicated that concatenation significantly destabilises the native structure of HP0242 to the extent that it resembles the global unfolding effect induced by concentrated chaotrophic agent, suggesting that knotting by concatenation may be thermodynamically unfavourable.

Results

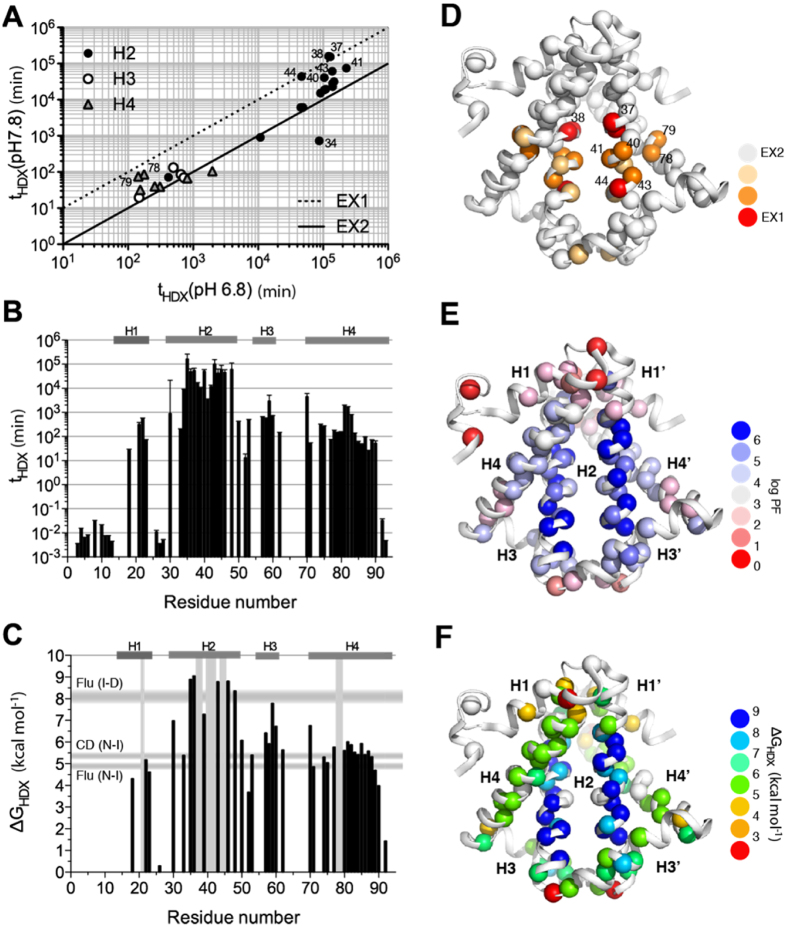

We have previously reported the backbone NMR assignments of wt HP0242 and the secondary structures in solution state are consistent with the crystal structure28. {1H}-15N heteronuclear nuclear Overhauser effect (hetNOE) of HP0242 confirmed that all the four helices are highly ordered on the timescale of ps-ns (Figure S1). Given that the unfolding kinetics of HP0242 variants under native conditions are on the timescale of hours to days, we opted to examine the slow folding dynamics of HP0242 by native NMR hydrogen-deuterium exchange (HDX)16,17,29 for slow-exchanging amide groups and phase-modulated clean chemical exchange (CLEANEX-PM)30 for fast exchanging amide groups, mostly the N-terminal region. The time constants of residue-specific amide HDX at pH 6.8 spanned from 102 to 106 minutes with those corresponding to the second helix (H2) being the slowest (Fig. 1). We repeated the same NMR HDX analysis at pH 7.8 to examine the pH-dependency of backbone amide HDX. While the HDX rates of most of the residues were proportional to catalyst concentration, i.e., [OH−], indicating that the HDX process is under thermodynamic equilibrium, also known as the EX2 regime31, a few residues showed pH independent HDX rates, indicating that the HDX of these residues are under kinetic control of the opening rates of the corresponding hydrogen bonds, also known as the EX1 regime. For the EX2 residues, we calculated the protection factor (PF), and derived the corresponding free energy of unfolding, ΔGHDX, for individual backbone amide-mediated hydrogen bonds (see Methods). The results showed that H2, which is stabilised by leucine-zipper hydrophobic interactions has the higher free energy of unfolding up to 9 kcal mol−1, which is close to the bulk number corresponding to the transient between intermediate and denatured (I-D) states of HP0242 derived from intrinsic fluorescence26. The average free energy of unfolding of H1 and H4 is closer to the values corresponding to the native to intermediate (N-I) states of HP0242 derived from intrinsic fluorescence and far-UV circular dichroism spectroscopy. Collectively, these data reaffirmed the sequential unfolding pathway established by bulk spectroscopic measurements in which the peripheral helices, namely H1, H3 and H3 unfold first followed by unfolding of the long H2 that is stabilised by leucine zipper-based homodimerisation26.

Figure 1. NMR HDX analysis of HP0242.

(A) Comparison of the HDX time constants of HP0242 obtained at pH 6.8 and pH 7.8. The solid and dashed lines correspond to the expected correlations of the times constants under the EX2 and EX1 conditions. The residues in helices 2 (H2), 3 (H3) and 4 (H4) are shown in filled circles, open circle and grey triangle, respectively. Those that deviate significantly from the EX2 condition are labelled with the residue numbers. (B) HDX time constants as a function of residue number. (C) ΔGHDX as a function of residue number. The locations of the EX1 residues are indicated by vertical grey bars. The ranges of free energies of unfolding for native-to-intermediate (NI) and intermediate-to-denatured (ID) derived from far-UV CD and intrinsic fluorescence are shown as horizontal grey bars as indicated on the left. (D–F) Structural mappings of the individual NMR HDX-derived parameters as shown in panels (A–C). The amide nitrogen atoms are shown in spheres with colour coding as indicated on the right hand side.

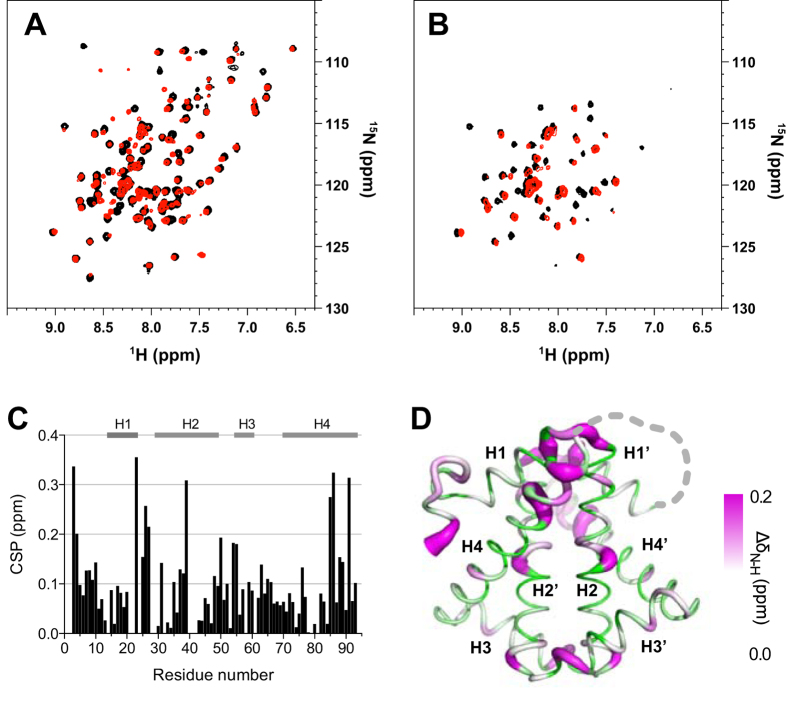

While our earlier work indicated that concatenated HP0242 exhibits more complex folding pathways with slower folding rates, possibly due to the increased likelihood of off-pathway folding intermediate formation, the molecular details of the impact on structure and folding dynamics upon concatenation of HP0242 remains elusive. We compared the backbone amide 15N-1H correlations of wt HP0242 and its concatenated form (Fig. 2). While the overall appearance of the two spectra were comparable, significant chemical shift perturbations were observed in the loop connecting H1 and H2 as well as most of H3, in addition to the flanking ends, i.e., the N- and C-termini as a result of concatenation. Furthermore, minor cross-peaks were observed in the 15N-1H correlation spectrum of the concatenated HP0242 due to the loss of internal symmetry. Remarkably, despite the spectral similarity between native and concatenated HP0242, the latter showed dramatic loss of NMR signals after a short period (<10 min) of HDX in contrast to a much larger number of the remaining correlations for wt HP0242 dimer, indicating that concatenation significantly destabilises the native structure of HP0242 despite the essentially identical structures resolved in crystalline state under cryogenic conditions.

Figure 2. Impact of concatenation on HP0242.

Overlay of 15N-1H correlation spectra of wt (black) and concatenated HP0242 (red) before (A) and after 10 min of HDX (B). (C) Weighted chemical shift perturbation (CSP) resulting from concatenation as a function of residue number. CSP is defined as ΔδN-H = [(ΔδN)2 + (ΔδH/6.5)2]1/2. (D) Structural mapping of the observed CSP onto the crystal structure of concatenated HP0242 (PDB entry: 3MLG) with the radius of the sausage representation being proportional to the size of CSP as indicated on the right hand side of the colour scale. The sites of concatenation are connected by dashed grey line.

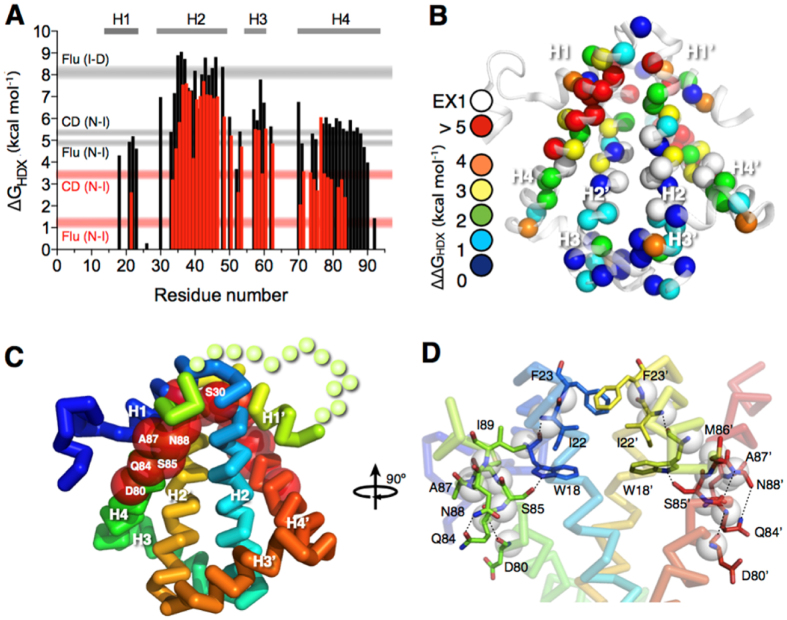

To further examine how concatenation impacts the folding of HP0242, we repeated the NMR HDX analysis for the concatenated form and found markedly reduced folding stabilities in H4 with its C-terminal half being so destabilised that no reliable HDX rates could be determined (Fig. 3). Likewise, most residues of H1 underwent rapid HDX that resulted in near-completely loss of protection against HDX. For H2 and H3, they were destabilised by as much as 2 kcal mol−1 across their whole sequences. Structural mapping of the residue-specific reduced free energy of unfolding showed that the impacts are localised near the concatenation site. Residues that are destabilised by more than 5 kcal mol−1 include S30, D80, Q84, S85, A87, N88 and I89. Other significantly destabilised residues (ΔΔG > 4 kcal mol−1) include W18, I22 and F23, all of which are located in close proximity to the only tryptophan residue of the protomer, W18. In addition to the backbone hydrogen bonds of the helical structure, the side-chain hydroxyl group of S85 is hydrogen bonded to the indole nitrogen of W18, whose intrinsic fluorescence serves as the structural probe in our earlier study26. It is likely that the introduction of covalent linkage between the C-terminus of one protomer to the N-terminus of the other through a short flexible linker imposes so much strain to the local structure around the C-terminal half of H4 that the corresponding hydrogen bond network is bulged from ideal geometry in solution.

Figure 3. Concatenation destabilizes local structures of HP0242.

(A) ΔGHDX as a function of residue number. The results of wt and tandem HP0242 are shown in black and red bars, respectively. The ranges of free energies of unfolding for native-to-intermediate (NI) and intermediate-to-denatured (ID) derived from far-UV CD and intrinsic fluorescence are shown in horizontal grey (wt) and red (concatenated) bars as indicated on the left. (B) Structural mapping of the destabilization effect of concatenation. Individual backbone amide nitrogen atoms are shown in spheres and their respective ΔΔGHDX = ΔGHDX(wt) − ΔGHDX(concatenated) values are colour-coded as indicated on the left. (C) Ribbon representation of concatenated HP0242 that is colour-ramped from blue to red for N- to C-termini, respectively. Residues that exhibit the largest destabilising effects are shown in red spheres and the identities are indicated in white letters. (D) Local structure of the destabilised region. Residues that are most destabilised are shown in stick representations and the inter-residue hydrogen bonds are shown in black dashed lines.

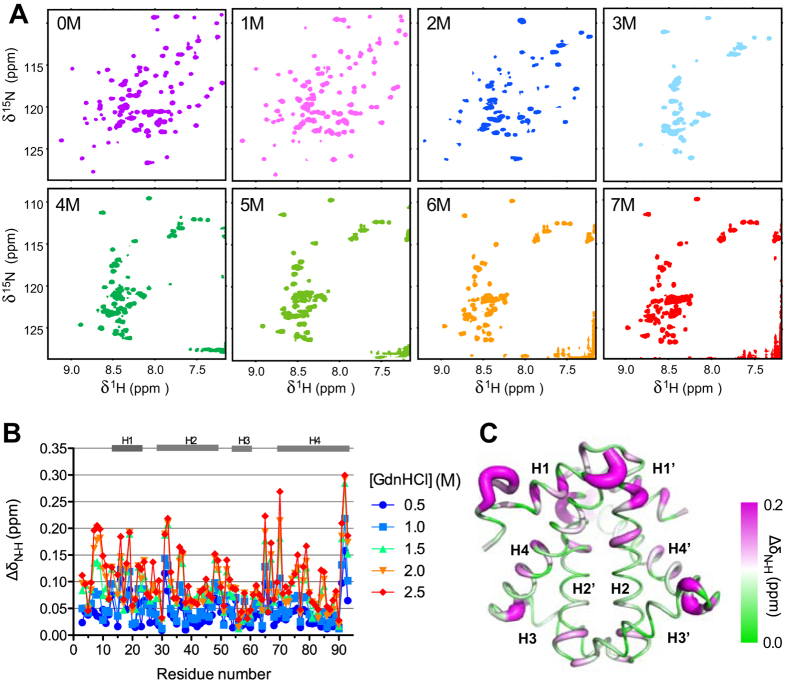

The large destabilising effect as a result concatenation prompted us to compare it with the destabilisation effect in response to chaotrophic agent-induced chemical denaturation. A series of 15N-1H correlation spectra of wt HP0242 were recorded in the presence of different concentrations of guanidine hydrochloride (GdnHCl) ranging from 0 to 7 M (Fig. 4). On increasing GdnHCl concentration, the intensities of well-dispersed 15N-1H correlations diminished progressively until they were too weak to be detected at 3 M GdnHCl. The chemical shift perturbations of individual 15N-1H correlations could be followed up to 2.5 M GdnHCl. Structural mapping of the observed chemical shift perturbations resemble remarkably with those observed in response to concatenation in that many of the highly perturbed residues are clustered around the junction between H1 and H4 where W18 is located. Several residues located at the fraying ends of the H3 and H2 also exhibited significant chemical shift perturbations. The loss of native 15N-1H correlation signals was accompanied by emergence of a group of poorly dispersed 15N-1H correlations, corresponding to unfolded population. Coexistence of native and chemically denatured 15N-1H correlations could be observed clearly at 2 M GdnHCl. Note however, that at near saturation denaturant concentration, i.e., 7 M GdnHCl, the number of unfolded 15N-1H correlations was far smaller than the expected number for a fully disordered polypeptide chain of 92 residues in length, suggesting that a significant proportion of the chemically denatured HP0242 was in a molten globular state with abundant conformation exchange processes on the timescale of μs to ms, resulting in severe line broadening.

Figure 4. Chemical denaturation of HP0242 monitored by NMR.

(A) A series of 15N-1H SOFAST-HMQC spectra were recorded for HP0242 in the presence of various amounts of GdnHCl as indicated in each panel. (B) Weighted chemical shift perturbation ΔδN-H as a function of residue number, and denaturant concentration (from 0.5 to 2.5 M GdnHCl, with colour coding from blue to red as indicated on the right hand side). The residues that are in helical regions in the native state are indicated by grey bars on the top of panel B and numbered from H1 to H4 according to the reported the crystal structure of HP0242 (PDB entry: 2BO3). (C) Structural mapping of the weighted chemical shift perturbations of HP0242 in the presence of 2.5 M GdnHCl compared to those in native condition (red symbols in (B)). The size of the radius of the sausage representation corresponds to the magnitude of the chemical shift perturbation. It is also colour-ramped from green to magenta as indicated on the right hand side.

Discussion

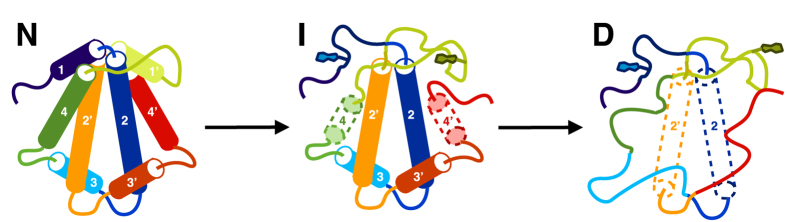

In this work, we have compared the folding dynamics of wt and concatenated HP0242 using native NMR HDX analysis. Despite the essentially identical crystal structures of the two variants24, our results indicated that concatenation through a flexible linker between the two protomers results in substantial destabilisation across the entire structure with many residues showed reduced free energy of unfolding by more than 2 kcal mol−1 while the C-terminal half of H4 and most of H1, both of which are directly involved in concatenation, are destabilised by more than 4 kcal mol−1. The global destabilising effects led us to compare them with chaotropic agent-induced global destabilisation by NMR. The results revealed a high degree of similarity between the two types of destabilisation in terms of their spatial distributions on the structure of HP0242. Furthermore, significantly fewer than expected number of 15N-1H correlations in the presence of 7 M GdnHCl suggests the existence of residual structures, most likely populated within H2 due to its high stability derived from NMR HDX, that undergo helix-coil transitions on the μs to ms timescale, resulting in unfavourable line broadening beyond detection. Combining all the experimental evidence, we propose a linear folding pathway for concatenated HP0242 along which a partially unfolded folding intermediates become highly populated with the secondary structural elements around W18, namely H1, H4 and part of H2, being largely disordered. In the presence of highly concentrated GdnHCl (>6 M), subsequent unfolding of H3 and H2 takes place to form a molten globular denatured state (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Proposed folding pathway of concatenated HP0242.

The secondary structure elements are colour-ramped from blue to red from the N- to the C-termini with the helices numbered from one to four for the N-terminal half and those of the C-terminal half are numbered in the same way with additional apostrophes. The tryptophan side-chains are shown explicitly in the cartoon representation. In the intermediate (I) and denatured (D) states, the partially unfolded helices are shown in dashed cylinders.

Protein repeats occur naturally through evolution32,33. Tremendous efforts have been made to engineer protein tandem repeats based on naturally occurring modules34,35,36,37,38,39,40 or de novo computational modules41,42. In most cases, the engineered protein tandem repeats display exceptionally high thermal and/or chemical stabilities compared to their ancestry building modules due to favourable enthalpic gains from inter-modular interactions and entropic stabilisation through covalent loop linkages34,37,39,41,43. A recent study by Tawfik and co-workers has nonetheless demonstrated through evolution traits that the stabilisation of the native states of β-propeller protein repeats is accompanied by parallel stabilisation of folding intermediates that are prone to misfold and aggregate40. Indeed, evolution tends to avoid high sequence similarity between neighbouring domains due to the higher propensity to misfold44,45. Theoretical and experimental analyses on the folding pathways of a series of circular permutations of β-trefoil interleukin-1β with different loop insertions suggested that these circular permutants tend to back-track on its folding landscape46, and that the destabilising effects can be attributed to geometric frustration of functional loops linking the modular repeats within the β-trefoil topology47. Collectively, these findings are in line with the fact that HP0242 exhibits complex folding pathways with high tendency to form off-pathway misfolded intermediates; the concatenated HP0242 exhibits significantly more populated folding intermediate than the intertwined symmetric dimer26. Our current findings highlighted the extra layer of complexity, in other words, energetic costs, involved in attaining the knotted topology of the concatenated form of HP0242. While knotting may be thermodynamically unfavourable, emerging evidence has revealed the functional importance of protein knots48 thus justifying their preservation throughout evolution.

Methods

Recombinant protein preparation

Uniformly 15N-labelled wt and concatenated HP0242 were over-expressed and purified according to the previously described protocol26,28. Unless otherwise specified, the NMR samples were buffered in 10 mM phosphate (pH 6.8) containing 10% D2O (v/v) and 0.02% NaN3.

NMR spectroscopy

All NMR data were collected at 298 K using an AVANCE 800 (18.7 T), an AVANCE III 600 (14.0 T) or an AVANCE 500 (11.7 T) NMR spectrometer (Bruker Biospin, Germany). The latter two are equipped with a cryogen-cooled probe head. Unless otherwise specified, 5 mm quartz NMR tubes were used for data collection. The resulting datasets were processed by NMRPipe49 and analysed by Sparky50. {1H}-15N hetNOE was recorded at 14.0 T using parameters as described previously51.

Chemical denaturation monitored by NMR spectroscopy

Aliquots of 0.1 mM 15N-labelled wt HP0242 were incubated in the presence of 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7 M GdnHCl overnight before NMR measurements. To minimize the interference from high salt contents during NMR measurements, 3 mm MATCH NMR tubes were used. 15N-1H SOFAST-HMQC52 spectra were recorded at 18.7 T (800 MHz proton Larmor frequency) using a room temperature probe. The chemical shifts of individual native backbone amide 15N-1H correlations were followed as a function of GdnHCl concentration up to 2.5 M at which point most of the native 15N-1H correlations are broadened beyond detection.

NMR hydrogen exchange (HX)

The rates at which the backbone amide protons exchange with bulk solvent are determined HDX29,31 and CLEANEX-PM30. NMR HDX of wt and tandem HP0242 was carried out using the previously described protocol. Briefly, aliquots of pH-adjusted protein solution were lyophilized overnight and equal amounts of 99% D2O were added to resuspend the sample powder immediately before the NMR HDX measurements. The NMR HDX data were collected at 14.0 T by recording a series of 15N-1H SOFAST-HMQC spectra over a period of 20 days29. For fast HX processes of wt HP0242, CLEANEX-PM was used to determine the HX rates in 90% H2O and 10% D2O (v/v) at pH 6.8. The pH values of the samples were confirmed after the NMR HDX measurements. For both HP0242 variants, two pH values (7.8 and 6.8) were used to ascertain whether the subjects of interest are in the EX1 or EX2 regime. The HDX rate constants (kex) of individual residues were used to derive the protection factors (PFs) using the Excel spreadsheet with built-in parameters that are available from the Englander group (hx2.med.upenn.edu/download.html). PF is the ratio of the intrinsic HDX rate (kint) over the observed HDX rate (kex), PF = kint/kex. For the EX2 residues, the corresponding PFs are subsequently converted into the free energy of unfolding, ΔGHDX, where, ΔGHDX = −RT ln(PF).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hsu, S.-T. D. Protein knotting through concatenation significantly reduces folding stability. Sci. Rep. 6, 39357; doi: 10.1038/srep39357 (2016).

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the funding of Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST104–2113-M-001–016) and Academia Sinica, Taiwan. S.-T.D.H. was supported by a Career Development Award from the International Human Frontier Science Program. The NMR data were collected at the High-field NMR Center in Academia Sinica. Liang-Wei Wang’s assistance in preparing the NMR samples was very much appreciated.

Footnotes

Author Contributions S.T.D.H. conceived and conducted the experiments, analysed the results and wrote the manuscript.

References

- Jamroz M. et al. KnotProt: a database of proteins with knots and slipknots. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D306–14 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y. L., Yen S. C., Yu S. H. & Hwang J. K. pKNOT: the protein KNOT web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W420–4 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virnau P., Mallam A. & Jackson S. Structures and folding pathways of topologically knotted proteins. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 23, 033101 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim N. C. & Jackson S. E. Molecular knots in biology and chemistry. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 27, 354101 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallam A. L. & Jackson S. E. A comparison of the folding of two knotted proteins: YbeA and YibK. J. Mol. Biol. 366, 650–65 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallam A. L. & Jackson S. E. Use of protein engineering techniques to elucidate protein folding pathways. Proc. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 84, 57–113 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallam A. L., Morris E. R. & Jackson S. E. Exploring knotting mechanisms in protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 18740–5 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallam A. L., Rogers J. M. & Jackson S. E. Experimental detection of knotted conformations in denatured proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 8189–94 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S.-J. M., Mallam A. L., Jackson S. E. & Hsu S.-T. D. Backbone NMR assignments of a topologically knotted protein in urea-denatured state. Biomol. NMR Assign. 8, 283–285 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh S.-J. M., Mallam A. L., Jackson S. E. & Hsu S.-T. D. Backbone NMR assignments of a topologically knotted protein in urea-denatured state. Biomol. NMR Assign. 8, 439–442 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih P.-M. et al. Random-coil behavior of chemically denatured topologically knotted proteins revealed by small-angle X-ray scattering. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 5437–5443 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallam A. L. & Jackson S. E. Knot formation in newly translated proteins is spontaneous and accelerated by chaperonins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 147–53 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I., Chen S.-Y. & Hsu S.-T. D. Unraveling the folding mechanism of the smallest knotted protein, MJ0366. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 4359–4370 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang I., Chen S. Y. & Hsu S.-T. D. Folding analysis of the most complex Stevedore’s protein knot. Sci. Rep. 6, 31514 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson F. I., Pina D. G., Mallam A. L., Blaser G. & Jackson S. E. Untangling the folding mechanism of the 5(2)-knotted protein UCH-L3. FEBS J. 276, 2625–35 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson F. I. et al. The effect of Parkinson’s-disease-associated mutations on the deubiquitinating enzyme UCH-L1. J. Mol. Biol. 407, 261–272 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou S.-C. et al. The knotted protein UCH-L1 exhibits partially unfolded forms under native conditions that share common structural features with its kinetic folding intermediates. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 2507–2520 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowska J. I., Sulkowski P. & Onuchic J. Dodging the crisis of folding proteins with knots. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 3119–24 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowska J. I., Noel J. K. & Onuchic J. N. Energy landscape of knotted protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 17783–8 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulkowska J. I. et al. Knotting pathways in proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 41, 523–7 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel J. K., Onuchic J. N. & Sulkowska J. I. Knotting a protein in explicit solvent. J. Phys. Chem. Letters 4, 3570–3573 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Faisca P. F. Knotted proteins: A tangled tale of structural biology. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 13, 459–68 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisca P. F., Travasso R. D., Charters T., Nunes A. & Cieplak M. The folding of knotted proteins: insights from lattice simulations. Phys Biol 7, 16009 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King N. P., Jacobitz A. W., Sawaya M. R., Goldschmidt L. & Yeates T. O. Structure and folding of a designed knotted protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 20732–7 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai J. Y. et al. Crystal structure of HP0242, a hypothetical protein from Helicobacter pylori with a novel fold. Proteins 62, 1138–43 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.-W., Liu Y.-N., Lyu P.-C., Jackson S. E. & Hsu S.-T. D. Comparative analysis of the folding dynamics and kinetics of an engineered knotted protein and its variants derived from HP0242 of Helicobacter pylori. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 27 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Terakawa T., Wang W. & Takada S. Energy landscape and multiroute folding of topologically complex proteins adenylate kinase and 2ouf-knot. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 17789–94 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien C.-T. H. et al. NMR assignments of a hypothetical pseudo-knotted protein HP0242 from Helicobacter pylori. Biomol. NMR Assign. 8, 287–289 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S.-T. D. et al. Folding study of Venus reveals a strong ion dependence of its yellow fluorescence under mildly acidic conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4859–4869 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang T. L., van Zijl P. C. & Mori S. Accurate quantitation of water-amide proton exchange rates using the phase-modulated CLEAN chemical EXchange (CLEANEX-PM) approach with a Fast-HSQC (FHSQC) detection scheme. J Biomol NMR 11, 221–6 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna M. M., Hoang L., Lin Y. & Englander S. W. Hydrogen exchange methods to study protein folding. Methods 34, 51–64 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte E. M., Pellegrini M., Yeates T. O. & Eisenberg D. A census of protein repeats. J. Mol. Biol. 293, 151–60 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., den Dulk-Ras A., Hooykaas P. J. & Glover J. N. Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirC2 enhances T-DNA transfer and virulence through its C-terminal ribbon-helix-helix DNA-binding fold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 9643–8 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortajarena A. L., Mochrie S. G. & Regan L. Mapping the energy landscape of repeat proteins using NMR-detected hydrogen exchange. J. Mol. Biol. 379, 617–26 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main E. R., Xiong Y., Cocco M. J., D’Andrea L. & Regan L. Design of stable alpha-helical arrays from an idealized TPR motif. Structure 11, 497–508 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramisch S., Weininger U., Martinsson J., Akke M. & Andre I. Computational design of a leucine-rich repeat protein with a predefined geometry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 17875–80 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripp K. W. & Barrick D. Enhancing the stability and folding rate of a repeat protein through the addition of consensus repeats. J. Mol. Biol. 365, 1187–200 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowling P. J., Sivertsson E. M., Perez-Riba A., Main E. R. & Itzhaki L. S. Dissecting and reprogramming the folding and assembly of tandem-repeat proteins. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 43, 881–8 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayre T. C., Lee T. M., King N. P. & Yeates T. O. Protein stabilization in a highly knotted protein polymer. Eng. Des. Sel. 24, 627–30 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smock R. G., Yadid I., Dym O., Clarke J. & Tawfik D. S. De Novo evolutionary emergence of a symmetrical protein is shaped by folding constraints. Cell 164, 476–86 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunette T. J. et al. Exploring the repeat protein universe through computational protein design. Nature 528, 580–4 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle L. et al. Rational design of alpha-helical tandem repeat proteins with closed architectures. Nature 528, 585–8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortajarena A. L. & Regan L. Calorimetric study of a series of designed repeat proteins: modular structure and modular folding. Protein Sci 20, 336–40 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgia M. B. et al. Single-molecule fluorescence reveals sequence-specific misfolding in multidomain proteins. Nature 474, 662–5 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgia A. et al. Transient misfolding dominates multidomain protein folding. Nat. Commun. 6, 8861 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capraro D. T., Roy M., Onuchic J. N. & Jennings P. A. Backtracking on the folding landscape of the beta-trefoil protein interleukin-1beta? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 14844–8 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capraro D. T., Gosavi S., Roy M., Onuchic J. N. & Jennings P. A. Folding circular permutants of IL-1beta: route selection driven by functional frustration. PLoS ONE 7, e38512 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian T. et al. Methyl transfer by substrate signaling from a knotted protein fold. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 941–48 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F. et al. NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J Biomol NMR 6, 277–93 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard T. D. & Kneller D. G. Sparky. 3.115 edn (University of California, San Francisco, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S.-T. D., Cabrita L. D., Fucini P., Dobson C. M. & Christodoulou J. Structure, dynamics and folding of an immunoglobulin domain of the gelation factor (ABP-120) from Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Mol. Biol. 388, 865–879 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanda P. & Brutscher B. Very fast two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy for real-time investigation of dynamic events in proteins on the time scale of seconds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 8014–5 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.