Abstract

Objective

This study reports the gynecologic conditions in postmenopausal women (intact uterus upon enrollment) in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR)/P-2 Trial.

Study Design

This study, with a median follow-up of 81 months, evaluated the incidence rates/risks of gynecologic conditions among women treated with tamoxifen and raloxifene.

Results

Compared to tamoxifen, women taking raloxifene had a lower incidence of uterine cancer (RR 0.55)/endometrial hyperplasia (RR 0.19), leiomyomas (RR 0.55), ovarian cysts (RR 0.60), endometrial polyps (RR 0.30) and had fewer procedures performed. Women on tamoxifen had more hot flashes (P < .0001), vaginal discharge (P <.0001), and vaginal bleeding (P < .0001).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that tamoxifen has more of an estrogenic effect on the gynecologic reproductive organs. These effects should be considered in counseling women on options for breast cancer prevention.

Keywords: Breast cancer prevention, gynecologic conditions, tamoxifen, raloxifene

Introduction

Breast cancer represents a major health hazard for women in the United States. Findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT) (P-1) resulted in tamoxifen being approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the prevention of breast cancer in high-risk women.1 Studies evaluating raloxifene in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis demonstrated a reduction in invasive breast cancer in postmenopausal women. These studies concluded that the risk of estrogen receptor-positive invasive breast cancer was decreased by 72% and by 66% with 4 and 8 years respectively, of raloxifene treatment.2,3 The NSABP P-2 trial, known as the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR), was launched to directly compare tamoxifen with raloxifene. The STAR/P-2 trial was a prospective, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of 19,747 healthy postmenopausal women at increased risk of breast cancer. The STAR/P-2 trial resulted in raloxifene’s being approved by the FDA for the prevention of breast cancer in high-risk women.4,5

This assessment was undertaken to report in detail on the gynecologic conditions occurring among postmenopausal women with an intact uterus upon enrollment in the STAR/P-2 trial.

Materials and Methods

This trial was approved by local human investigations committees or institutional review boards in accordance with assurances filed with and approved by the Department of Health and Human Services. Written informed consent was required for participation in this trial.

To be eligible for this trial, women had to be postmenopausal, at least 35 years of age, and have a 5-year predicted risk for breast cancer of at least 1.66%. Breast cancer risk was determined using the Gail model, as modified and applied in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (BCPT/P-1).6 The details of the STAR/P-2 methodology are described in the initial report of the study.4 The participants were randomly assigned to receive either 20 mg/d of tamoxifen plus placebo (9,736), or 60 mg/d of raloxifene plus placebo (9,754) for 5 years. Because the formulations of tamoxifen and raloxifene tablets were dissimilar, it was necessary to use placebo tablets to maintain the double blinding of treatment assignment. The enrollment period began on June 1, 1999, and ended on November 4, 2004. This report is based on a cut-off date of March 31, 2009.

Upon enrollment in the NSABP STAR/P-2 trial, the study population consisted of 9,456 postmenopausal women with an intact uterus. As in the BCPT trial,1,7 women were monitored for symptoms of hot flashes, vaginal discharge, vaginal dryness, and abnormal vaginal bleeding, and the occurrence of numerous gynecologic conditions diagnosed during the study period were reported, including: endometrial adenocarcinomas, endometrial hyperplasia, leiomyomas, polyps, endometritis, endometriosis, and ovarian cysts. Surgical interventions, such as dilatation and curettage, hysteroscopy, laparoscopy, oophorectomy, and hysterectomy were similarly recorded in the study database.

The chi square test was used to compare the raloxifene and tamoxifen groups with regard to age, parity, history of oral contraceptive use, history of estrogen therapy, number of relatives with breast cancer, history of diabetes and hypertension, smoking status, and body mass index (BMI). The chi square test was also used to compare treatment groups by distribution by severity of self-reported symptoms. The analyses of the incidence of gynecologic conditions and surgical procedures mentioned above were performed to evaluate the differences between treatment groups. These analyses were based on the determination of risk ratios (RRs) of the incidence rates by treatment group (raloxifene compared with tamoxifen) and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) on the RR. The incidence rates were calculated as the number of events divided by the person-years at risk. The 95% CIs were determined using the exact method assuming that the events followed a Poisson distribution, conditioning on the total number of events and person-years at risk.

Results were considered to be statistically significant if P < 0.05 or when the 95% CI for the RR did not include 1.00. The date file cut-off used for this analysis of March 31, 2009 was chosen to be consistent with that used for the update report of the main findings.5

Results

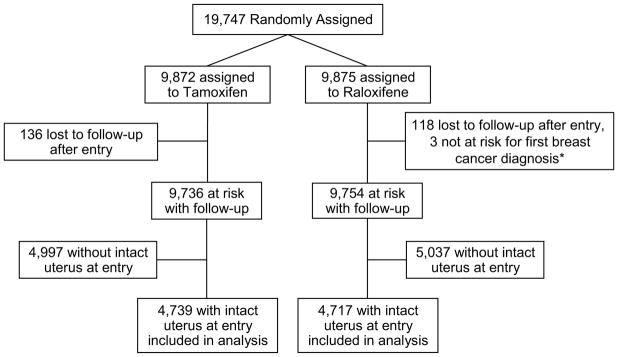

A total 4,739 women receiving tamoxifen and 4,717 women receiving raloxifene had an intact uterus upon entry (see CONSORT figure). The characteristics of the participants included in the current analysis are shown in Table 1. The groups were similar in baseline characteristics, including age, parity, BMI, history of oral contraceptive or estrogen use, family history of breast cancer, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking status. At a median follow-up of 81 months, significant differences existed in self-reported bothersome hot flashes (P < 0.0001), vaginal discharge (P < 0.0001) and vaginal bleeding (P < 0.0001) in patients receiving tamoxifen as compared with raloxifene (Table 2). Vaginal dryness was more common in patients receiving raloxifene (P<0.0001).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram: NSABP P-2

* Two women with bilateral mastectomy prior to entry and one woman with diagnosis of breast cancer prior to entry discovered after random assignment.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics at time of random assignment for women with an intact uterus at entry in the NSABP STAR/P-2 trial

| Participant Characteristic | Tamoxifen (n = 4739) | Raloxifene (n = 4717) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| No. | % | No. | % | P | |

| Age (years) | |||||

| ≤ 49 | 237 | 5.0 | 233 | 4.9 | 0.99 |

| 50–59 | 2592 | 54.7 | 2584 | 54.8 | |

| 60–69 | 1516 | 32.0 | 1515 | 32.1 | |

| ≥ 70 | 394 | 8.3 | 385 | 8.2 | |

| Mean (SD) | 58.8 (6.8) | 58.8 (6.8) | |||

| Parity | |||||

| ≤ 1 | 1252 | 26.4 | 1211 | 25.7 | 0.41 |

| ≥ 2 | 3487 | 73.6 | 3506 | 74.3 | |

| History of oral contraceptive use | |||||

| No | 1501 | 31.7 | 1540 | 32.6 | 0.31 |

| Yes | 3238 | 68.3 | 3177 | 67.4 | |

| History of estrogen therapy | |||||

| No | 1763 | 37.2 | 1823 | 38.6 | 0.15 |

| Yes | 2976 | 62.8 | 2894 | 61.4 | |

| No. of relatives with breast cancer | |||||

| 0 | 1489 | 31.4 | 1446 | 30.7 | 0.22 |

| 1 | 2399 | 50.6 | 2404 | 51.0 | |

| 2 | 710 | 15.0 | 752 | 15.9 | |

| 3 or more | 141 | 3.0 | 115 | 2.4 | |

| History of diabetes | |||||

| Yes | 241 | 5.1 | 227 | 4.8 | 0.54 |

| No | 4498 | 94.9 | 4490 | 95.2 | |

| History of hypertension | |||||

| Yes | 1417 | 29.9 | 1383 | 29.3 | 0.54 |

| No | 3322 | 70.1 | 3334 | 70.7 | |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 2414 | 50.9 | 2448 | 51.9 | 0.29 |

| Former | 1860 | 39.2 | 1780 | 37.7 | |

| Current | 443 | 9.3 | 458 | 9.7 | |

| Unknown | 22 | 0.5 | 31 | 0.7 | |

| BMI* | |||||

| <25.0 | 1619 | 34.2 | 1576 | 33.4 | 0.74 |

| 25.0 – 29.9 | 1638 | 34.6 | 1646 | 34.9 | |

| ≥ 30.0 | 1481 | 31.3 | 1494 | 31.7 | |

| Mean (SD) | 28.1(6.0) | 28.2 (6.1) | |||

BMI was unavailable for one person in the tamoxifen group and one person in the raloxifene group.

Table 2.

Highest level of self-reported symptoms disclosed by participants with an intact uterus at entry in the NSABP STAR/P-2 trial

| Symptoms/severity level | Tamoxifen (n = 4693)* | Raloxifene (n = 4669)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| No. | % | No. | % | P | |

| Hot flashes bothersome | |||||

| No | 670 | 14.3 | 774 | 16.6 | <.0001 |

| Slightly | 692 | 14.7 | 912 | 19.5 | |

| Moderately | 1020 | 21.7 | 1031 | 22.1 | |

| Quite a bit | 1339 | 28.5 | 1215 | 26.0 | |

| Extremely | 972 | 20.7 | 737 | 15.8 | |

| Vaginal discharge bothersome | |||||

| No | 1765 | 37.6 | 2673 | 57.2 | <.0001 |

| Slightly | 1276 | 27.2 | 1194 | 25.6 | |

| Moderately | 838 | 17.9 | 484 | 10.4 | |

| Quite a bit | 551 | 11.7 | 234 | 5.0 | |

| Extremely | 263 | 5.6 | 84 | 1.8 | |

| Vaginal dryness bothersome | |||||

| No | 1432 | 30.5 | 1315 | 28.2 | <.0001 |

| Slightly | 924 | 19.7 | 893 | 19.1 | |

| Moderately | 915 | 19.5 | 822 | 17.6 | |

| Quite a bit | 802 | 17.1 | 924 | 19.8 | |

| Extremely | 620 | 13.2 | 715 | 15.3 | |

| Vaginal bleeding bothersome | |||||

| No | 3548 | 75.6 | 4042 | 86.6 | <.0001 |

| Slightly | 666 | 14.2 | 443 | 9.5 | |

| Moderately | 233 | 5.0 | 100 | 2.1 | |

| Quite a bit | 153 | 3.3 | 53 | 1.1 | |

| Extremely | 93 | 2.0 | 31 | 0.7 | |

Forty-six women in the tamoxifen group and 48 women in the raloxifene group opted not to complete follow-up quality-of-life questionnaires.

The average annual rates of invasive uterine cancer, hyperplasia (with and without atypia), and hysterectomy during follow-up are shown in Table 3. The incidence of invasive cancer was 45% lower in the raloxifene group compared with the tamoxifen group (RR=0.55, 95% CI= 0.36–0.83). The risk of endometrial hyperplasia was almost 80% higher among women in the tamoxifen group as compared with those in the raloxifene group (RR=0.19; 95% CI = 0.12–0.29). Of those with hyperplasia, 82.5% had hyperplasia without atypia. The rate of hysterectomy for conditions other than invasive cancer in the tamoxifen group was more than twice that in the raloxifene group (RR=0.45; 95% CI=0.37–0.54), suggesting that the rates of invasive cancer and hyperplasia in the tamoxifen group would have been higher than actually observed if there were no differential in the rates of hysterectomy.

Table 3.

Average annual rates of uterine disease in the NSABP STAR/P-2 trial

| Type of Uterine Disease | Number of Events | Rate per 1000 | Risk Ratio (RR)† | RR 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamoxifen | Raloxifene | Tamoxifen | Raloxifene | Difference* | |||

|

|

|

||||||

| Invasive cancer | 65 | 37 | 2.25 | 1.23 | 1.02 | 0.55 | 0.36 to 0.83 |

| Hyperplasia | 126 | 25 | 4.40 | 0.84 | 3.56 | 0.19 | 0.12 to 0.29 |

| Without atypia | 104 | 21 | 3.63 | 0.70 | 2.93 | 0.19 | 0.11 to 0.31 |

| With atypia | 22 | 4 | 0.77 | 0.13 | 0.64 | 0.17 | 0.04 to 0.51 |

| Hysterectomy during follow-up‡ | 349 | 162 | 12.08 | 5.41 | 6.67 | 0.45 | 0.37 to 0.54 |

Rate in the tamoxifen group minus rate in the raloxifene group.

Risk ratio for women in the raloxifene group compared with women in the tamoxifen group.

For conditions other than invasive cancer.

Women were also evaluated for other gynecologic conditions and surgical procedures (Table 4). Women taking raloxifene had a decreased incidence of leiomyomata (RR = 0.55; 95% CI = 0.49–0.62), ovarian cysts (RR = 0.60; CI = 0.49–0.74), polyps (RR = 0.30; 95% CI = 0.25–0.35), and endometriosis (RR = 0.32; 95% CI = 0.24–0.43). They were also less likely to undergo dilation and curettage (RR = 0.30; 95% CI = 0.26–0.35), hysteroscopy (RR = 0.29; 95% CI =0.24–0.35), and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy or oophorectomy (RR = 0.50; 95% CI = 0.42–0.60).

Table 4.

Average annual rates of gynecological conditions and procedures by treatment group in the NSABP STAR P-2 trial

| Condition or Procedure | Number of Events | Rate per 1000 | Risk Ratio (RR)† | RR 95% Confidence Interval | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tamoxifen | Raloxifene | Tamoxifen | Raloxifene | Difference* | |||

| Conditions | |||||||

| Leiomyomas | 757 | 443 | 28.40 | 15.56 | 12.84 | 0.55 | 0.49 to 0.62 |

| Ovarian cysts | 236 | 147 | 8.32 | 5.01 | 3.31 | 0.60 | 0.49 to 0.74 |

| Polyps | 575 | 185 | 21.06 | 6.28 | 14.78 | 0.30 | 0.25 to 0.35 |

| Endometriosis | 190 | 64 | 6.60 | 2.14 | 4.46 | 0.32 | 0.24 to 0.43 |

| Procedures | |||||||

| Curettage | 673 | 218 | 24.30 | 7.32 | 16.98 | 0.30 | 0.26 to 0.35 |

| Bilateral oophorectomy | 371 | 192 | 12.80 | 6.46 | 6.34 | 0.50 | 0.42 to 0.60 |

| Laparoscopy | 14 | 4 | 0.46 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.07 to 0.90 |

| Hysteroscopy | 493 | 151 | 17.32 | 5.03 | 12.29 | 0.29 | 0.24 to 0.35 |

Rate in the tamoxifen group minus rate in the raloxifene group.

Risk ratio for women in the raloxifene group compared to women in the tamoxifen group.

Comment

Although gynecologic conditions were not considered the primary end point of the NSABP STAR/P-2 study, interesting data have emerged from careful follow-up of these women during the study period. While there are some limitations to the generalization of the findings as almost all (93.5%) of the STAR/P-2 participants were white and the average Gail score (4.03%) was very high, the findings provide very important unbiased comparisons of the relative efficacy and toxicity of tamoxifen and raloxifene.

Our study findings support that tamoxifen has more of an estrogenic effect on the gynecologic reproductive tract organs than does raloxifene. These findings include an increase risk of: (1) invasive endometrial cancer, (2) endometrial hyperplasia both with and without atypia, and (3) leiomyomas, polyps, and endometriosis. Our findings also support that tamoxifen has more effect on the ovaries with an increase incidence of ovarian cysts. This may be reflective of the chemical structure of tamoxifen and its similarity to clomiphene.8 In addition to increasing the risk of gynecologic conditions, the differential effects of tamoxifen and raloxifene also resulted in more procedures performed in the tamoxifen group, including hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, oophorectomy, hysteroscopy, and laparoscopy. With the average annual rate of hysterectomy for reasons other than uterine cancer in the tamoxifen group (12.08 per 1000) being more than double than that found in the raloxifene group (5.41 per 1000), the increased risk of invasive uterine cancer associated with tamoxifen is likely higher than that which was actually observed.

Raloxifene and tamoxifen are good preventive choices for higher-risk postmenopausal women at risk for breast cancer, and there are differing gynecologic effects with each, respectively. These differing gynecologic effects should be considered when counseling women with an intact uterus on options for breast cancer prevention.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by: Public Health Service grants U10-CA-37377, U10-CA-69974, U10-CA-12027, U10-CA-69651 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services; and by AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals and Eli Lilly and Company

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest

- Wickerham DL, Fisher B, Wolmark N, Bryant J, Costantino JP, Bernstein L, Runowicz CD. Association of tamoxifen and uterine sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 2002; 20(11):2758–60.

- Chalas E, Costantino J, Wickerham DL, Runowicz CD. Author Reply to Letter to the Editor on: Benign gynecologic conditions among participants in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 194(4):1205.

- Chalas E, Costantino J, Wickerham DL, Wolmark N, Lewis GC, Bergman C, Runowicz CD. Benign gynecologic conditions among participants in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192(4):1230–7; discussion 1237–9.

- Vogel V, Costantino J, Wickerham DL, Cronin WM, Cecchini RS, Atkins J, Bevers TB, Fehrenbacher L, Pajon ER, Wade JL, Robidoux A, Margolese R, James J, Lippman SM, Runowicz CD, Ganz PA, Reis SE, McCaskill-Stevens W, Ford LG, Jordan VC, Wolmark N. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: The NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA 2006;295(23):2727–41. Epub 2006. Jun 5. JAMA. 2006 Dec 27;296(24):2926.

- Land SR, Wickerham DL, Costantino J, Ritter M, Vogel V, Lee M, Pajon ER, Wade JL, Dakhil S, Lockhart JB Jr, Wolmark N, Ganz PA. Patient-reported symptoms and quality of life during treatment with tamoxifen or raloxifene for breast cancer prevention: The NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA 2006;295(23):2742–51. Epub 2006 Jun 5. JAMA. 2007 Sep 5;298(9):973

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fisher B, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Redmond CK, Kavanah M, Cronin W, et al. Tamoxifen for prevention of breast cancer: report of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project P-1 Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(18):1371–1388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.18.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cummings SR, Eckert S, Krueger KA, et al. The effect of raloxifene on risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: results from the MORE randomized trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation. JAMA. 1999;281:2189–2197. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.23.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martino S, Cauley JA, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Continued Outcomes Relevant to Evista: breast cancer incidence in postmenopausal osteoporotic women in a randomized trial of raloxifene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1751–1761. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: The NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2727–2741. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Update of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 Trial: Preventing breast cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2010;3(6):696–706. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costantino JP, Gail MH, Pee D, et al. Validation studies for models to project the risk of invasive and total breast cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1541–1548. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.18.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalas E, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Benign gynecologic conditions among participants in the Breast Cancer Prevention Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williamson JG, Ellis JD. The induction of ovulation of ovulation by tamoxifen. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Cmnwlth. 1973;80:844–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1973.tb11230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]