Abstract

Minigenes encoding the peptide Met–Arg–Arg have been used to study the mechanism of toxicity of AGA codons proximal to the start codon or prior to the termination codon in bacteria. The codon sequences of the ‘mini-ORFs’ employed were initiator, combinations of AGA and CGA, and terminator. Both, AGA and CGA are low-usage Arg codons in ORFs of Escherichia coli but, whilst AGA is translated by the scarce tRNAArg4, CGA is recognized by the abundant tRNAArg2. Overexpression of minigenes harbouring AGA in the third position, next to a termination codon, was deleterious to the cell and led to the accumulation of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 and of the peptidyl-tRNA cognate to the preceding CGA or AGA Arg triplet. The minigenes carrying CGA in the third position were not toxic. Minigene-mediated toxicity and peptidyl-tRNA accumulation were suppressed by overproduction of tRNAArg4 but not by overproduction of peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase, an enzyme that is only active on substrates that have been released from the ribosome. Consistent with these findings, peptidyl-tRNAArg4 was identified to be mainly associated with ribosomes in a stand-by complex. These and previous results support the hypothesis that the primary mechanism of inhibition of protein synthesis by AGA triplets in pth+ cells involves sequestration of tRNAs as peptidyl-tRNA on the stalled ribosome.

INTRODUCTION

Multicopy expression of genes that contain the Arg triplets AGA and AGG at positions very close to the initiation codon inhibits cell growth and protein synthesis. An example of this type of inhibition follows the expression of the lambda int gene, which harbours AGA and AGG triplets at positions 3 and 4 of the open reading frame (ORF) (1). Mutants that are defective in peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase (Pth) activity are more sensitive to such inhibition than are wild-type cells, and accumulate peptidyl-tRNAArg4 upon expression of the int gene (2). It has been proposed that int-mediated inhibition results from ribosome stalling at rare Arg codons and subsequent dissociation of peptidyl-tRNAArg4. To the best of our knowledge, however, convincing proof of this explanation has yet to be presented (1,2).

Peptidyl-tRNAs are intermediates in protein synthesis and are generated by the transfer of formyl-methionyl or peptidyl groups, bound to a tRNA at the ribosomal P-site, to an aminoacyl-tRNA located at the A-site on the translating ribosome. The peptidyl-tRNA of an elongating polypeptide at the codon next to the stop codon of a message is cleaved by the ribosomal peptidyl-transferase (3), whereas peptidyl-tRNAs prematurely released from the ribosome (drop-off) are hydrolysed by Pth activity (4). Both of these processes regenerate tRNAs that can be reused in protein synthesis.

Short ORFs, encoding oligopeptides containing from two to seven amino acid residues, have been employed successfully as model systems in order to study translation in bacteria (5–8). The expression of some of these ORFs in so-called minigenes gives rise to toxicity in bacteria that are deficient in Pth activity by virtue of an accumulation of peptidyl-tRNAs (7–9). Such toxicity may stem from depletion of a specific aminoacyl-tRNA, essential for protein synthesis, the tRNA of which remains sequestered as a peptidyl-tRNA (10,11). In fact, the degree of toxicity elicited by expression of minigenes correlates closely with the levels of peptidyl-tRNA accumulated in the cells, and such toxicity can be suppressed by overproduction of the particular tRNA in the peptidyl-tRNA (7,12,13). It is likely that at least part of the peptidyl-tRNA that accumulates in Pth-defective cells results from drop-off because the effect can be reversed by overproduction of Pth (14), an enzyme that acts only on free substrates (15).

Toxicity is related to the length, sense and stop codon composition, and also to the level of minigene expression (7,8,13,16). Data obtained using minigenes carrying two-codon mini-ORFs of the sequence ATG NNN TAA (where NNN is any sense codon) suggest that toxicity in Pth-defective cells results from stalling of the ribosome at the NNN triplet prior to the termination codon in the mRNA. It is likely that peptidyl-tRNAs in stalled complexes eventually drop-off (13). From studies with cells defective in Pth, it has been shown that synthesis and drop-off of peptidyl-tRNA occurs during the translation of minigene mRNA. However, the accumulation of peptidyl-tRNA in stalled ribosomal complexes should occur in both wild-type and Pth-deficient cells. Conceivably, the formation of such complexes may be related to the observed minigene-mediated inhibition of protein synthesis and toxicity in wild-type cells (7,12). This toxicity can be suppressed by overproduction of the specific tRNA sequestered in the peptidyl-tRNA (12) but not by overproduction of Pth (14). These results support the assumption that peptidyl-tRNA is initially associated with the ribosome in a stand-by complex.

The molecular mechanism of toxicity is the subject of the present study. Minigenes harbouring the rare codon AGA immediately after the initiation codon, and/or preceding the termination triplet, have been expressed in cells containing wild-type levels of Pth activity. Minigenes containing two synonymous Arg codons were used as a model system, and the nature, levels and sub-cellular location of specific peptidyl-tRNAs were assessed. It is concluded that the toxicity observed in wild-type cells stems from ribosomes stalled on minigene mRNA resulting in the sequestration of tRNAs as peptidyl-tRNAs. These observations suggest a mechanism for the inhibition of protein synthesis and cell growth through the expression of normal genes containing AGA and AGG codons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids and toxicity assay

The Escherichia coli K-12 strains P90C [ara Δ(lac-pro) thi] and P90Crap [P90C pth (rap) zch::Tn10] used in the study were from our collection. The plasmids employed were (i) pPOT1AE (Apr) and its derivative pMR, carrying the minigene ATG AGA TAG (12); (ii) pGREC, a pACYC-based Cmr construct in which the EcoRV–BamH1 segment of the vector had been substituted with the E.coli pth+ gene under the control of Ptac (11); and (iii) pDC952, a pACYC derivative carrying argU encoding the cognate tRNA for AGA and AGG (17). In order to estimate the degree of toxicity of a minigene (Table 1), single colonies of either transformants harbouring the minigene constructs, or of co-transformants for pDC952 or pGREC, were streaked on plates of Luria–Bertani (LB) agar containing appropriate supplements [100 μg/ml ampicillin, 50 μg/ml chloramphenicol, 1 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG)].

Table 1. Viability effects during expression of different constructs in wild-type and Pth-deficient (rap) cells.

| Relevant codonsa | Wild-type cellsb |

Pth-deficient cellsb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (−)c | tRNAArg4c | pth+c | (−)c | tRNAArg4c | pth+c | |

| ATGAGAAGA | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| ATGCGAAGA | − | + | − | − | −/+ | − |

| ATGAGACGA | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| ATGCGACGA | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| ATGAGATAG | − | + | − | − | + | − |

aCodons in the minigene ORF sequence: the termination codon in the first four minigenes was TAA.

bWild-type or pth (rap) cells were transformed with the indicated constructs only (−), or co-transformed with pDC952 (tRNAArg4) or pGREC (pth+).

cGrowth on plates (Materials and Methods) was evaluated as (−), absence; (+), presence and (−/+), petite colonies.

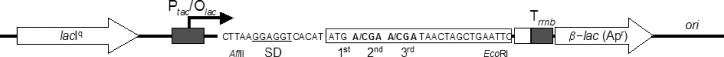

AGA/CGA minigenes

The set of constructs harbouring minigenes containing all four combinations of AGA and CGA was obtained by cloning duplex synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotides (oligos), under the control of the IPTG-inducible tac promoter, into the vector pPOT1AE (Figure 1) (12) as described previously (13). The four complementary synthetic oligos employed were 5′-TTAAGGAGGTCACAT ATG A/CGA A/CGA TAA CTAGCTG-3′ and 5′-AATTCAGCTAG TTA TCG/T TCG/T CATATGTGACCTCC-3′ (the cohesive ends of AflII and EcoRI are shown underlined and in boldface, respectively; slashes between two bases indicate that the corresponding NGA triplet can be A or C for the first oligo and G or T for the complement). The oligos were cloned into the vector restricted with both AflII and EcoRI.

Figure 1.

Map of the constructs used in this work. Upon addition of the gratuitous inducer IPTG the Lac repressor encoded by lacIq gene (open arrow) dissociates from the operator region Olac (grey box) and transcription initiates at promoter Ptac (bold arrow). Transcription presumably terminates at the transcriptional terminator Trrnb (grey box) The minigene ORFs encode the tripeptide Met–Arg–Arg from the initiator, ATG, through combinations of the triplets AGA and CGA in pairs at codon positions 2 and 3 to the terminator codon TAA. The transcripts are translated from a Shine–Dalgarno sequence (SD, underlined) appropriately spaced from the initiator triplet AUG. The constructs were selected by resistance to ampicillin (Apr) conferred by the gene β-lac which encodes β-lactamase. The relative position of the replication origin in the construct (ori) and the position of the restriction sites employed are indicated (see Materials and Methods).

Analysis of the distribution of peptidyl-tRNA

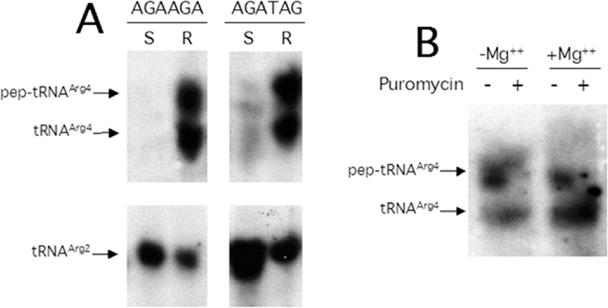

In order to analyse the content of peptidyl-tRNA in ribosomes and in supernatant fractions (Figure 2 and Table 3), cultures (50 ml) of transformed cells were shaken at 37°C until they attained an OD (at 600 nm) of 0.3, after which minigene expression was induced by the addition of IPTG (2 mM). Cultures were incubated for a further 40 min, centrifuged (5000 g, 20 min) and the cellular pellets re-suspended in 10 ml of buffer I [10 mM magnesium acetate, 20 mM potassium acetate, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 1 mM dithiothreitol]. Re-suspended cells were disrupted in a French press and the extracts centrifuged (30 000 g, 30 min) in order to sediment the debris. Supernatants were centrifuged (100 000 g, 90 min) at 4°C, and the pellets containing the ribosomes were re-suspended in 500 μl of buffer II [0.1 M sodium acetate, 0.5 M sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA and 1% SDS (pH 5.0)]: the soluble fractions were diluted 10-fold in buffer II. Peptidyl-tRNA levels in pellets and the diluted soluble fractions were estimated (Tables 2–5) by electrophoresis and northern blot assays as described by Cruz-Vera et al. (13).

Figure 2.

Distribution of tRNAArg variants and the effect of puromycin on the peptidyl-tRNA associated with ribosomes. (A) Cell-free extracts from P90C transformants induced for expression of minigenes ATG AGA AGA TAA (AGA AGA) and ATG AGA TAG (AGA TAG) were separated by centrifugation into S100 supernatant (S) and ribosome (R) fractions and further analysed by northern blot (see Materials and Methods). The peptidylated (pep), aminoacylated (aa) and free species of tRNAArg4 or tRNAArg2 were revealed by blots using 32P-labelled oligonucleotide probes specific for each tRNA as described in Cruz-Vera et al. (13). (B) The ribosomes obtained from P90C, transformed and induced for minigene expression, were suspended in buffer I with (+ Mg2+) or without (− Mg2+) magnesium acetate and incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 2.5 mM puromycin for 10 min at 37°C. The tRNA-containing variants were revealed as described above.

Table 3. The percentages of peptidyl-tRNAs in the supernatant (S100) and ribosomal pellet of wild-type and Pth-deficient (rap) cell-free extracts.

| Relevant codons | Wild-type cells |

Pth-deficient cells |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S100 |

Ribosome |

S100 |

Ribosome |

|||||

| Peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (%)a | Peptidyl-tRNAArg2 (%)a | Peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (%)a | Peptidyl-tRNAArg2 (%)a | Peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (%)a | Peptidyl-tRNAArg2 (%)a | Peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (%)a | Peptidyl-tRNAArg2 (%)a | |

| ATG AGA AGA | 1 ± 1 | 2 ± 1 | 59 ± 5 | 3 ± 1 | 11 ± 3 | 1 ± 1 | 80 ± 8 | 2 ± 1 |

| ATG CGA AGA | 3 ± 2 | 2 ± 1 | 9 ± 2 | 16 ± 4 | 34 ± 7 | 24 ± 7 | 50 ± 8 | 44 ± 7 |

| ATG AGA TGA | 7 ± 2 | 3 ± 1 | 45 ± 9 | 2 ± 2 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

aPercentage of peptidyl-tRNA relative to the total amount of tRNA: free tRNA in the S100 supernatant and ribosome pellet plus peptidyl-tRNA in the S100 supernatant and ribosomal pellet. The values shown are means of two independent experiments ± mean error.

Table 2. The percentages of peptidyl-tRNAs accumulated during expression of different minigene constructs in wild-type and Pth-deficient (rap) cells.

| Relevant codonsa | Wild-type cells | Pth-deficient cells | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (%)b | Peptidyl-tRNAArg2 (%)b | Peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (%)b | Peptidyl-tRNAArg2 (%)b | |

| ATG AGA AGA | 60 ± 9 | 3 ± 1 | 89 ± 5 | 5 ± 2 |

| ATG CGA AGA | 14 ± 4 | 15 ± 4 | 86 ± 4 | 66 ± 7 |

| ATG AGA CGA | 18 ± 4 | 4 ± 2 | 68 ± 5 | 77 ± 4 |

| ATG CGA CGA | 3 ± 1 | 10 ± 3 | 5 ± 2 | 86 ± 4 |

| ATG AGA TAG | 50 ± 8 | 4 ± 2 | 58 ± 7 | 3 ± 2 |

aThe termination codon in the first four minigenes was TAA. The AGA codon is read by tRNAArg4 whereas the CGA codon is decoded by tRNAArg2.

bThe cultures of the different transformed cells were grown at 37°C to OD (at 600 nm) of 0.6 on LB–ampicillin medium and induced for minigene expression. The percentages of peptidyl-tRNAs were calculated relative to the indicated tRNAs according to Cruz-Vera et al. (13); the values shown are means of two independent experiments ± mean error.

Table 5. The percentages of peptidyl-tRNAs accumulated during expression of minigene constructs in the presence of Pth overexpression.

| Relevant codons | Wild-type cellsa | Pth-deficient cellsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (%)b | Peptidyl-tRNAArg2 (%)b | Peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (%)b | Peptidyl-tRNAArg2 (%)b | |

| ATG AGA AGA | 52 ± 9 | 3 ± 2 | 63 ± 8 | 5 ± 2 |

| ATG CGA AGA | 13 ± 4 | 15 ± 6 | 11 ± 5 | 20 ± 5 |

| ATG AGA TGA | 49 ± 8 | 4 ± 2 | 53 ± 9 | 5 ± 2 |

aWild-type or Pth-deficient cells bearing the indicated minigene constructs and pGREC, which carries the pth+ gene were grown on LB containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol. The cultures were processed to estimate the percentage of peptidyl-tRNAs as described in Table 2.

bThe values shown are means of two independent experiments ± mean error.

In the experiment to determine the effect of puromycin on the peptidyl-tRNA associated with ribosomes (shown in Figure 2B), cultures were induced as indicated above but divided into two equal portions prior to centrifugation: one cellular pellet was re-suspended in buffer I, and the other in the same buffer minus the magnesium acetate. Re-suspended cells were disrupted in a French press, the extracts centrifuged (30 000 g; 30 min) and the supernatants incubated in the presence or absence of 2.5 mM puromycin for 10 min at 37°C. Ribosomal pellets and soluble fractions were obtained by centrifugation and the levels of peptidyl-tRNA estimated as described above.

RESULTS

The AGA triplet is responsible for minigene toxicity

In a random sample of minigenes that are toxic to wild-type cells, it was observed (12) that two low-usage Arg codons (AGA and AGG) next to the stop codon were over-represented. In order to investigate the mechanism of this toxicity, we have compared the AGA triplet, cognate to the scarce tRNAArg4, with the CGA triplet, a low-usage Arg codon recognized by the abundant tRNAArg2 (18,19), as control. Multicopy expression of the dipeptide minigenes ATG AGA and ATG CGA provokes accumulation of peptidyl-tRNAs and is toxic to the Pth-defective cells (13). Combinations of the two triplets, AGA and/or CGA, flanked by initiator (ATG) and stop (TAA) codons were placed in constructs under the same Ptac promoter–operator and Shine–Dalgarno sequences (Figure 1). This design permitted the analysis of codon–anticodon interactions, and their effect on minigene toxicity, whilst preserving the composition of the encoded tripeptide. Wild-type and pth-defective transformants containing the different constructs were streaked on LB plates, and minigene expression was induced by the addition of IPTG (see Materials and Methods). The absence of growth (−) indicated that expression of minigenes carrying all four possible codon combinations inhibited the growth of a pth strain, a result that was expected from consideration of previous data obtained using dipeptide minigenes (13). In contrast, however, for tripeptide minigenes only the combinations AGA AGA and CGA AGA prevented growth of wild-type cells (Table 1, rows 1 to 4 data columns 1 and 4).

Differences between AGA and CGA triplets in minigene-mediated inhibition

The toxicity of minigenes bearing an AGA triplet at the last sense position in pth-defective cells is related to sequestration of the cognate tRNAArg4 as its peptidyl-derivative (12). It has been shown that this toxicity is readily alleviated by overproduction of either tRNAArg4 or Pth in the pth-mutant cell (12,14). We compared the effects of constructs leading to overproduction of tRNAArg4 and Pth on the inhibition of growth of wild-type and pth-mutant cells mediated by the expression of tripeptide minigenes. The results showed that overproduction of tRNAArg4 effectively suppressed the inhibition resulting from overexpression of the minigenes ATG AGA AGA and ATG CGA AGA in wild-type cells, but an excess of Pth was ineffective in reversing this inhibition (Table 1; rows 1 and 2, data columns 1 to 3). In the pth-mutant, the overproduction of tRNAArg4 was only partly effective in suppressing toxicity of the minigene ATG CGA AGA. However, overproduction of Pth readily suppressed the inhibition provoked by minigenes ATG AGA CGA and ATG CGA CGA (Table 1; rows 3 and 4, data columns 5 and 6), but not that produced by the ATG AGA AGA and ATG CGA AGA minigenes.

These results suggest that the toxicity of the minigenes ATG AGA AGA and ATG CGA AGA is related to the inhibition of protein synthesis arising from ribosome stalling. The translation of mRNAs of a minigene harbouring an AGA triplet at the last sense position could deplete the pool of tRNAArg4 that could be aminoacylated, thus causing the peptidyl-tRNA at the previous codon to remain in the P-site of the paused ribosome: in this case an excess of tRNAArg4 would restore translation elongation. On the other hand, the toxicity of ATG AGA CGA and ATG CGA CGA minigenes is due to peptidyl-tRNA drop-off, i.e. the minigene messengers bearing a CGA triplet at the last sense codon tend to drop-off peptidyl-tRNAArg2 by a delay in termination hydrolysis (13). When there is limiting Pth activity, peptidyl-tRNAArg2 builds up in the cell; in such cases an excess of Pth hydrolyses the soluble substrate thus restoring protein synthesis. We assume that levels of Pth in wild-type cells are sufficient to hydrolyse the peptidyl-tRNAArg2 produced by drop-off.

Decoding of AGA triplet in minigene messengers leads to the accumulation of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 in wild-type cells

In cases where peptidyl-tRNA could be measured, a strict correlation between the levels of accumulated peptidyl-tRNA and the toxicity of the minigenes expressed in Pth-defective mutants has been reported (13). However, in the presence of the fully active Pth in wild-type cells, the only measurable peptidyl-tRNA would be in complexes protected from enzyme activity such as, e.g. on paused ribosomes. In order to determine the relationship between peptidyl-tRNA and toxicity in wild-type cells, the ratio of peptidyl- to free-tRNAs for tRNAArg4 and tRNAArg2 in extracts from bacteria induced for minigene expression were assessed from northern blots (13). The results (Table 2) show that, regardless of codon composition, minigenes expressed in Pth-defective cells promoted the accumulation of higher concentrations of peptidyl-tRNAs cognate to the Arg codons in the second and third positions (data columns 3 and 4) compared with those produced by wild-type cells (data columns 1 and 2). It is likely that depletion of the tRNA specific for the last sense codon in the message provoked stalling of the translating ribosome with the peptidyl-tRNA cognate to the previous codon.

In the wild-type strain, the toxic minigene ATG AGA AGA gave rise to an accumulation of 60% peptidyl-tRNAArg4: this was the highest relative concentration encountered in the minigenes assayed (Table 2, first row), and was clearly a consequence of the presence of the AGA triplet at both Arg codon positions. However, no correlation between the level of accumulated peptidyl-tRNAArg4 and toxicity was observed. Thus, the non-toxic construct ATG AGA CGA accumulated a level (18%) of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 similar to that (15%) produced by the toxic ATG CGA AGA minigene (Table 2, rows 2 and 3, data columns 1 and 2). On the other hand, the latter accumulated more peptidyl-tRNAArg2 than did the non-toxic minigenes ATG AGA CGA and ATG CGA CGA. These results may be explained by assuming that translation of minigene messengers containing AGA triplets in the third position, unlike those carrying AGA in the second codon position, depleted the pool of tRNA which decode the previous codon. In this case, peptidyl-tRNAArg drop-off may not be the reason for the toxicity, since, in the presence of normal levels of Pth activity, peptidyl-tRNA would be readily cleaved. According to this scheme, the CGA triplet next to the terminator triplet would not be toxic either because tRNAArg2, being more abundant than tRNAArg4, would not be critically reduced (19), and/or because the nature of the codon–anticodon interaction facilitates drop-off. Our explanation leads to three predictions concerning tRNAArg4: (i) peptidyl-tRNAArg at the second codon in toxic minigenes should be found on the ribosomes in stalled complexes; (ii) increasing the supply of free-tRNAArg4 should provide sufficient substrate for the stalled ribosomes in order for translation to continue thereby reducing the amount of peptidyl-tRNAArg at the second codon; and (iii) increasing the supply of Pth should not release the stalled ribosome because Pth does not act on ribosome-bound peptidyl-tRNA.

Peptidyl-tRNA is in a ribosomal complex in wild-type cells

In order to test the first of our predictions, cell-free extracts from cultures induced for minigene expression were fractionated by ultracentrifugation to yield an S100 supernatant and a ribosomal sediment. The fractions were submitted to electrophoresis and analysed for peptidyl-tRNA by northern blot assays (see Materials and Methods). The results (Table 3) show that all of the peptidyl-tRNAArg4 resulting from the expression of the tripeptide minigene ATG AGA AGA in wild-type and pth-mutant cells was to be found in the ribosomal fraction (Table 3, data columns 1, 3, 5 and 7), whereas control tRNAArg2, which is not used in the translation of these mRNAs, was distributed approximately equally between the soluble and the ribosomal fraction (Table 3, data columns 2, 4, 6 and 8). Furthermore, peptidyl-tRNAArg2 and peptidyl-tRNAArg4 generated during expression of the tripeptide minigene ATG CGA AGA in wild-type cells were found mainly in the ribosomal fraction, albeit in only modest (10 and 16%, respectively) amounts (Table 3, second row, data columns 1 to 4). In pth-mutant cells, the two peptidyl-tRNAs were distributed more evenly between the ribosomal and S100 fractions and, not surprisingly, were present in higher amounts (Table 3, data columns 5 to 8). These results suggest that drop-off of the peptidyl-tRNA cognate to the last sense codon yields a substrate that is cleaved readily by Pth activity in the wild-type strain, and that the peptidyl-tRNA generated by decoding of the previous triplet may drop-off as well. In order to prove that the peptidyl-tRNAArg4 was indeed in a paused complex with ribosomes and not simply precipitated as an artefact with the ribosomal sediment, the ribosomes were treated with puromycin, which acts as a peptide acceptor of peptidyl-tRNAs located in the ribosomal P-site. The results (Figure 2B) indicate that the peptidyl-tRNAArg4 associated with ribosomes was reduced to 10% following treatment with puromycin (Figure 2B, lane 4). Ribosomal dissociation in the absence of Mg2+ reduced the level of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 to 40% (Figure 2B, lane 2) probably as a result of hydrolysis by the Pth activity normally associated with ribosomes (20). These findings, taken together, indicate that the peptidyl-tRNAArg4 resulting from toxic AGA-containing minigenes remains associated with ribosomes in a paused translation complex.

Overproduction of tRNAArg4 alleviates the accumulation of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 promoted by the tripeptide minigenes ATG NGA AGA

Table 4 shows the results of an experiment carried out to test the prediction that suppression of minigene-mediated toxicity by overproduction of tRNAArg4 in wild-type cells would reduce the levels of peptidyl-tRNAArg4. Overproduction of tRNAArg4 by a construct that increased the cellular concentration of tRNAArg4 by a factor of 10 (data not shown) gave rise to a reduction in the fraction of peptidyl-tRNA generated by expression of ATG AGA AGA from 60 to 10% (Table 2). This effect may not represent a real net reduction in the amount of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 since it was overproduced. (i) During the expression of the ATG CGA AGA minigene, overproduction of tRNAArg4 provoked an actual decrease in the cellular level of peptidyl-tRNAArg2 from 15 to 3.5%. (ii) After correction for the 10-fold overproduction of tRNAArg4, the expression of the ATG AGA TAG minigene also generated higher levels of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (see below). We believe that these results indicate that production of an excess of tRNAArg4 releases the stalled ribosomes by allowing decoding of the starved AGA codons in minigene and cellular mRNAs.

Table 4. The percentages of peptidyl-tRNAs accumulated during expression of minigene constructs in the presence of tRNAArg4 overexpression.

| Relevant codons | Wild-type cellsa | Pth-deficient cellsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (%)b | Peptidyl-tRNAArg2 (%)b | Peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (%)b | Peptidyl-tRNAArg2 (%)b | |

| ATG AGA AGA | 10 ± 4 | 3 ± 1 | 65 ± 9 | 4 ± 2 |

| ATG CGA AGA | 15 ± 4 | 4 ± 2 | 67 ± 9 | 23 ± 5 |

| ATG AGA TGA | 37 ± 8 | 4 ± 1 | 43 ± 8 | 5 ± 2 |

aWild-type or Pth-deficient pth(rap) cells bearing the indicated minigene constructs and pDC952, a construct harbouring the gene that encodes tRNAArg4, were grown on LB medium containing ampicillin and chloramphenicol. The cultures were processed to estimate the percentage of peptidyl-tRNAs as described in Table 2.

bThe values shown are means of two independent experiments ± mean error.

In pth-mutant bacteria, the reduction in the levels of minigene-mediated peptidyl-tRNAArg4 following overproduction of tRNAArg4 was only 30% (Tables 2 and 4). We believe that this modest effect results from the fact that in Pth-defective cells, most of the accumulated peptidyl-tRNAArg4 is not associated with ribosomes and, therefore, an excess in tRNAArg4 has no effect on its level. However, the observation (Tables 2 and 4) that an excess of tRNAArg4 reduced by 3-fold (from 66 to 23%) the accumulation of peptidyl-tRNAArg2 during translation of the ATG CGA AGA minigene in pth-mutant cells, indicates that translation of the last codon reduces the level of peptidyl-tRNA at the penultimate codon by allowing elongation of the peptide chain.

The accumulation of peptidyl-tRNA mediated by an AGA dipeptide minigene continues in the presence of excess tRNAArg4

Expression of the minigene ATG AGA TAG proved to be toxic to wild-type cells in a manner similar to that observed for the tripeptide minigenes ATG AGA AGA and ATG CGA AGA analysed above. Such expression promoted the accumulation of peptidyl-tRNA (Tables 1 and 2) and the toxicity was reversed by overproduction of tRNAArg4 (Table 1) (12). Expression of minigenes ATG AGA TAG and ATG AGA AGA yielded some 3 to 4 times more peptidyl-tRNAArg4 than the toxic minigene ATG CGA AGA (Table 2, data column 1): in all three cases the tRNAArg4 was mainly located on the ribosomes (Table 3). After probing for peptidyl- and free-tRNAArg4 following expression of the first two minigenes, it was established that half of the tRNAArg4 on the ribosomes was not peptidylated (Figure 2A). Control tRNAArg2, which was not used in these minigenes, was not peptidylated and was detected in both the soluble and the ribosomal fractions. Thus, toxic minigene messengers appear to sequester most of the cellular tRNAArg4 in the ribosome as peptidyl-RNA and probably as aminoacylated tRNA when AGA is at the second codon position.

Reversion, by overexpression of tRNAArg4, of ATG AGA AGA minigene-mediated toxicity was accompanied by a reduction in the percentage concentration of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 (Tables 2 and 4). However, the effect of overproduction of tRNAArg4 on the accumulation of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 promoted by the expression of the dipeptide minigene ATG AGA TAG in wild-type cells was strikingly different from that observed with the tripeptide minigene. Whereas a 6-fold reduction in the percentage of peptidyl-tRNA (from 60 to 10%) was observed with the minigene ATG AGA AGA, the reduction was only 1.4-fold (from 50 to 36%) with the dipeptide minigene (Tables 2 and 4). Allowing for a 10-fold increase in the level of tRNAArg4 by overexpression (data not shown), the 6-fold reduction in percentage of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 actually represents a 1.7-fold increase in level, whilst the 1.4-fold reduction with the dipeptide minigene implies a 7-fold increase in the actual amount of peptidyl-tRNAArg4. This finding indicates that, upon tRNAArg4 overproduction, the minigene ATG AGA TAG continues accumulating peptidyl-tRNAArg4 more rapidly than the ATG AGA AGA minigene.

These results may be explained by assuming that somewhat different events occur with the two minigenes upon tRNAArg4 depletion. Whereas the peptidyl-tRNAArg4 accumulated by minigene ATG AGA TAG stems from a defect in translation termination hydrolysis, the peptidyl-tRNAArg4 build-up by minigene ATG AGA AGA results from the inability of the translation machinery to decode the AGA triplet at the third codon position. It would be expected that the latter complex, but not the former, would be released by providing an excess of tRNAArg4.

The overproduction of Pth had no effect on the accumulated peptidyl-tRNA in wild-type cells (Tables 2 and 5) as would be expected if it were protected in a ribosomal complex. In pth-mutant cells, overproduction of Pth reduced the accumulation of peptidyl-tRNA generated by minigene expression: for ATG AGA AGA the percentage of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 decreased from 89 to 63%, whereas for ATG CGA AGA the decrease in peptidyl-tRNAArg4 was from 85 to 11% and the reduction in peptidyl-tRNAArg2 was from 66 to 20% (Tables 2 and 5). These decreases are roughly proportional to the percentages of the respective peptidyl-tRNAs in the S100 fractions for the pth (rap) cells namely 11, 34 and 24%, respectively (Table 3), and this is consistent with the fact that Pth acts only on free peptidyl-tRNAs.

DISCUSSION

The inhibition of protein synthesis and cell growth mediated by expression of genes harbouring AGA triplets seems to be caused by ribosome pausing. In wild-type cells, translation of di- and tri-peptide minigene messengers harbouring AGA triplets at the last sense position provoked stalling of ribosomes carrying the peptidyl-tRNA specific for the starved AGA codons and for the previous triplet. These complexes resulted from depletion of charged tRNAArg4, the isoacceptor that recognizes the AGA triplet (11), and probably contained the minigene mRNA, a premise that may be inferred from the observed correlation between the stability of the minigene mRNA and the accumulation of peptidyl-tRNA for toxic minigenes (13,16). Thus, the peptidyl-tRNAs on the stalled ribosomes eventually drop-off and appear in solution in the presence of limited Pth activity (Table 2, data column 3 and 4). Although it has been proposed that drop-off from efficiently translated minigenes may overload the normal Pth capacity of wild-type strains (11,12), no significant levels of peptidyl-tRNA in solution were detected in northern blots of RNA from wild-type cells (Figure 2A).

The overexpression of minigenes containing AGA triplets, drastically change codon usage in the cell by demanding more Arg-tRNAArg4 for translation of the minigene messengers and thus limiting its availability for other cell messengers. This is very similar to the effect explained by a model based on the limitation of an amino acid for aminoacylation of tRNA (21). It is likely that minigene-mediated inhibition stems from a reduction in the pool of Arg-tRNAArg4 following sequestration of the tRNA as peptidyl-tRNAArg4 at the P-site of stalled ribosomes. The tRNA may also be sequestered as Arg-tRNAArg4 at the A-site or as tRNAArg4 at the E-site because non-peptidylated tRNA variants were also found associated with the ribosomal complexes (Figure 2A). We consider it unlikely that the inhibition of protein synthesis results from the sequestration of ribosomes themselves as stalled complexes. In the most extreme case of accumulation of ribosomal complexes, as observed with the minigene AGA AGA, all of the tRNAArg4 was present in the ribosomal fraction (Figure 2A). Assuming that each tRNAArg4 molecule was in a different stalled complex, which may not be the case since some ribosomes may contain a peptidyl-tRNA and an aminoacyl-tRNAArg4 (A-site) or a free-tRNAArg4 (E-site), only 17% of the ribosomes would be stalled on the mRNAs (19). Calculation of the fraction of ribosomes in complexes in wild-type cells that had been inhibited by expression of the minigene CGA AGA yielded a similar value. It has been shown that ribosome stalling at clusters of rare arginine codons prior to an inefficient termination codon in mRNA, recruit and activate the SsrA peptide tagging system for degradation (22). The presence of peptidyl-tRNAArg4 complexes in stand-by ribosomes on minigene messengers suggests that the SsrA peptide tagging system (23,24) is unable to liberate them. It is possible that the SsrA system is ineffective on AGA codons located in short ORFs.

The presence of peptidyl-tRNA and tRNA in ribosomes is induced not only after minigene expression, in which stalling is prompted by a stop codon (13), but also after expression of normal genes where the ribosomes seem to pause at a sense codon cognate to a scarce tRNA early after translation initiation. The expression of a modified lacZ, in which the initial codon sequence was AUG AGA AGA CCC …, was toxic to wild-type cells, and at least part of the tRNAArg4 and the peptidyl-tRNAArg4 were found associated with ribosomes (E. Zamora-Romo, unpublished data). This result may be related to the fact that the tRNAPro, which recognizes CCC, is a relatively scarce isoacceptor cognate to a low-usage codon. Evidence from other laboratories implicates two sets of E.coli translation factors in the stimulation of peptidyl-tRNA drop-off, namely, the elongation factor EF-G and release factors RF3 and RRF (25), and the initiation factors IF1 and IF2 (6). In this context it is worth noting that in vitro factor-induced drop-off can occur both at sense and stop codons in the ribosomal A-site upon starvation for release factors RF1 and RF2 or for the tRNA cognate to the next sense codon, respectively.

In contrast, the lambda int gene, which has the AGA and AGG triplets (both cognate to tRNAArg4) at ORF positions 3 and 4, did not show association of peptidyl-tRNA with ribosomes (2). However, this result is not necessarily inconsistent with the data presented here. Presumably ribosome stalling at the AGA codon occurs in the mRNAs of both int and ATG A/CGA AGA minigenes, but different subsequent codons favour dissimilar responses. Whereas for int mRNA, overproduction of tRNAArg4 prevents drop-off by allowing translation to move forward to the next codon, for the minigene messengers it continues feeding peptidyl-tRNA to the codon next to the stop codon until it is terminated by ribosomal transferase activity.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Guadalupe Aguilar González for skilful technical support, Philippe Régnier and associates at The Institut de Biologie Physico-Chimique for generous hospitality that made possible the composition of early versions of this paper, and Jon Gallant, Charles Yanofsky and an anonymous referee for critical review and comments on the manuscript. G.G. was a Université de Paris VII visiting professor and was awarded a sabbatical fellowship by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) Mexico. The study was financed by grants from CONACyT [28401N and 37759N to G.G., and O28 (ER025) to Julio Collado Vides (UNAM)] and from the Consejo Nacional de Educación Tecnológica (COSNET) Mexico. L.R.C.-V. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from COSNET and funds from CONACyT (grant O28).

REFERENCES

- 1.Zahn K. and Landy,A. (1996) Modulation of lambda integrase synthesis by rare arginine tRNA. Mol. Microbiol., 21, 69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olivares-Trejo J.J., Bueno-Martínez,J.G., Guarneros,G. and Hernández-Sánchez,J. (2003) The pair of arginine codons AGA AGG close to the initiation codon of the lambda int gene inhibits cell growth and protein synthesis by accumulating peptidyl-tRNAArg4. Mol. Microbiol., 49, 1043–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hershey J.W.B. (1987) Protein synthesis. In Neidthardt,F.G. (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium Cellular and Molecular Biology. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC, pp. 613–647. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menninger J.R. (1976) Peptidyl transfer RNA dissociates during protein synthesis from ribosomes of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem., 251, 3392–3398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tenson T., Xiong,L., Kloss,P. and Mankin,A.S. (1997) Erythromycin resistance peptides selected from random peptide libraries. J. Biol. Chem., 272, 17425–17430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karimi R., Pavlov,M.Y., Heurgué-Hamard,V., Buckingham,R.H. and Ehrenberg,M. (1998) Initiation factors IF1 and IF2 synergistically remove peptidyl-tRNAs with short polypeptides from the P-site of translating Escherichia coli ribosomes. J. Mol. Biol., 281, 241–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinçbas V., Heurgué-Hamard,V., Buckingham,R.H., Karimi,R. and Ehrenberg,M. (1999) Shutdown in protein synthesis due to the expression of mini-genes in bacteria. J. Mol. Biol., 291, 745–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heurgué-Hamard V., Dinçbas,V., Buckingham,R.H. and Ehrenberg,M. (2000) Origins of minigene-dependent growth inhibition in bacterial cells. EMBO J., 19, 2701–2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ontiveros C., Valadez,J.G., Hernández,J. and Guarneros,G. (1997) Inhibition of Escherichia coli protein synthesis by abortive translation of phage lambda minigenes. J. Mol. Biol., 269, 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernández-Sánchez J., Valadez,J.G., Vega Herrera,J., Ontiveros,C. and Guarneros,G. (1998) Lambda bar minigene-mediated inhibition of protein synthesis involves accumulation of peptidyl-tRNA and starvation for tRNA. EMBO J., 17, 3758–3765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindsley D., Gallant,J. and Guarneros,G. (2003) Ribosome bypassing elicited by tRNA depletion. Mol. Microbiol., 48, 1267–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tenson T., Herrera,J.V., Kloss,P., Guarneros,G. and Mankin,A.S. (1999) Inhibition of translation and cell growth by minigene expression. J. Bacteriol., 181, 1617–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cruz-Vera L.R., Hernández-Ramón,E., Pérez-Zamorano,B. and Guarneros,G. (2003) The rate of peptidyl-tRNA dissociation from the ribosome during minigene expression depends on the nature of the last decoding interaction. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 26065–26070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oviedo N.A., Salgado,H., Collado-Vides,J. and Guarneros,G. (2004) Distribution of minigenes in the bacteriophage lambda chromosome. Gene, 329, 115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kossel H. (1970) Purification and properties of peptidyl-tRNA hydrolase from Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 204, 191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valadez J.G., Hernández-Sánchez,J., Magos,M.A., Ontiveros,C. and Guarneros,G. (2001) Increased bar minigene mRNA stability during cell growth inhibition. Mol. Microbiol., 39, 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Tito B. Jr, Ward,J., Hodgson,J., Gershater,C., Edwards,H., Wysocki,L., Watson,F., Sathe,G. and Kane,J. (1995) Effects of a minor isoleucyl tRNA on heterologous protein translation in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol., 177, 7086–7091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curran J.F. (1995) Decoding with the A:I wobble pair is inefficient. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 683–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong H., Nilsson,L. and Kurland,C.G. (1996) Co-variation of tRNA abundance and codon usage in Escherichia coli at different growth rates. J. Mol. Biol., 260, 649–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menninger J.R. and Walker,C. (1974) An assay for protein chain termination using peptidyl-tRNA. Methods Enzymol., 30, 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elf J., Nilsson,D., Tenson,T. and Ehrenberg,M. (2003) Selective charging of tRNA isoacceptors explains patterns of codon usage. Science, 300, 1718–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keiler K.C., Waller,P.R. and Sauer,R.T. (1996) Role of a peptide tagging system in degradation of proteins synthesized from damaged messenger RNA. Science, 271, 990–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roche E.D. and Sauer,R.T. (1999) SsrA-mediated peptide tagging caused by rare codons and tRNA scarcity. EMBO J., 18, 4579–4589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayes C.S., Bose,B. and Sauer,R.T. (2002) Stop codons preceded by rare arginine codons are efficient determinants of SsrA tagging in Escherichia coli. PNAS, 99, 3440–3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heurgué-Hamard V., Karimi,R., Mora,L., MacDougall,J., Leboeuf,C., Grentzmann,G., Ehrenberg,M. and Buckingham,R.H. (1998) Ribosome release factor RF4 and termination factor RF3 are involved in dissociation of peptidyl-tRNA from the ribosome. EMBO J., 17, 808–816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]