Abstract

Background

Patients with incurable cancer face many physical and emotional stressors, yet little is known about their coping strategies or the relationship between their coping strategies, quality of life (QOL) and mood.

Methods

As part of a randomized trial of palliative care, this study assessed baseline QOL (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General), mood (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), and coping (Brief COPE) in patients within 8 weeks of a diagnosis of incurable lung or gastrointestinal cancer and before randomization. To examine associations between coping strategies, QOL, and mood, we used linear regression, adjusting for patients’ age, sex, marital status, and cancer type.

Results

Participant Sample

There were 350 participants (mean age, 64.9 years), and the majority were male (54.0%), were married (70.0%), and had lung cancer (54.6%). Most reported high utilization of emotional support coping (77.0%), whereas fewer reported high utilization of acceptance (44.8%), self-blame (37.9%), and denial (28.2%). Emotional support (QOL: β = 2.65, P < .01; depression: β = −0.56, P = .02) and acceptance (QOL: β = 1.55, P < .01; depression: β = −0.37, P = .01; anxiety: β = −0.34, P = .02) correlated with better QOL and mood. Denial (QOL: β = −1.97, P < .01; depression: β = 0.36, P = .01; anxiety: β = 0.61, P < .01) and self-blame (QOL: β = −2.31, P < .01; depression: β = 0.58, P < .01; anxiety: β = 0.66, P < .01) correlated with worse QOL and mood.

Conclusion

Patients with newly diagnosed, incurable cancer use a variety of coping strategies. The use of emotional support and acceptance coping strategies correlated with better QOL and mood, whereas the use of denial and self-blame negatively correlated with these outcomes. Interventions to improve patients’ QOL and mood should seek to cultivate the use of adaptive coping strategies.

Keywords: Coping Behavior, Quality of Life, Depression, Anxiety, Incurable Cancer, Palliative Care

Precis

Patients with a new diagnosis of incurable cancer cope in a variety of unique ways. We found that patients’ use of certain coping strategies correlated with their QOL and mood, suggesting that evaluating and addressing patients’ coping behaviors may impact other key patient-reported outcomes.

Introduction

Patients with incurable cancer often endure numerous physical and emotional challenges as they cope with a life-limiting illness. Not only do these patients have to deal with the notion that they have a terminal diagnosis, they also often experience high symptom burden and encounter a variety of difficult medical decisions.1–3 Specifically, patients must decide if the benefits of treatment outweigh the significant toxicities and unwanted side effects of cancer therapy.4, 5 How patients cope with their illness can influence their ability to make decisions regarding both their cancer care and their care at the end of life.6–9 Additionally, patients’ use of certain coping strategies can affect their desire for information about their disease, their self-efficacy, and how they adjust to the disease and its treatment.10–13 However, little is known about how patients cope with a diagnosis of incurable cancer.

Although patients with incurable cancer confront numerous stressors, the relationship between their coping strategies, quality of life (QOL) and psychological distress has not been fully evaluated. The existing literature in the general cancer population suggests that certain strategies are more commonly utilized and adaptive than others,7, 9, 14–17 but studies have not yet evaluated coping and its relationship with other outcomes in patients with a new diagnosis of incurable cancer. Adaptive coping strategies generally refer to more positive or constructive coping responses that may benefit patients in certain situations, while maladaptive coping strategies refer to those that are more negative or dysfunctional.18 Importantly, patients with incurable cancer may cope differently than those with curable disease, as they often experience greater symptom burden and emotional distress related to their life threatening illness.1, 19–21 Additionally, understanding the strategies used most frequently by this population and the associations between their coping strategies and well-being is particularly important, as patients with newly diagnosed, incurable cancer are often asked to make rapid and difficult decisions about their cancer treatment. Use of certain coping strategies may impact patients’ perceptions of their illness and influence their decisions regarding treatment, which can have a lasting impact on their treatment course and ultimately their end-of-life outcomes.8, 13, 22, 23 Thus, an understanding of the relationship between patients’ coping strategies and their QOL and mood will allow us to better support patients as they navigate their new diagnosis of incurable cancer.

In the present analysis of baseline data from a randomized trial of early palliative care, we sought to investigate how patients with incurable cancer cope with their illness. We also examined the associations between patients’ coping strategies and their QOL and mood. By studying the relationship between incurable cancer patients’ coping strategies, QOL and mood, we aim to highlight both the adaptive and maladaptive strategies that can be addressed in future interventions.

Methods

Study Design

As part of a randomized trial of early palliative care, we enrolled patients within eight weeks of their diagnosis of incurable cancer. All medical oncologists agreed to recruit and obtain consent from their patients. After providing written informed consent, we asked participants to complete baseline measures prior to their randomization assignment and notification of study arm allocation. Study staff subsequently obtained clinical data from the medical record. The Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Care Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Patient Selection

The sample included ambulatory patients at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center with confirmed, incurable lung or non-colorectal gastrointestinal (GI) cancer diagnosed within the previous eight weeks, not receiving treatment with curative intent, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 to 2, age ≥ 18 years and the ability to read and respond to questions in English. We confirmed the non-curative intent of therapy by reviewing the chemotherapy consent forms in the electronic medical record. Patients who were already receiving consultation from the palliative care service were not eligible for study participation.

Study Measures

Sociodemographic and Clinical Factors

Participants completed a demographic questionnaire that included race, ethnicity, religion, marital status, smoking history, income, and education level. We reviewed participants’ electronic medical records to obtain data on their age, sex, cancer diagnosis and stage, ECOG performance status, and cancer therapy.

Quality of Life

We measured self-reported QOL using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G).24 The FACT-G contains 28 items with subscales assessing well-being across four domains (physical, functional, emotional and social) during the past week. Scores on the FACT-G range from 0 to 112, with higher scores indicating a better QOL.

Depression and Anxiety

We measured patients’ depression and anxiety symptoms using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).25 The HADS is a 14-item questionnaire that contains two 7-item subscales assessing depression and anxiety symptoms during the past week. Scores on each subscale range from 0 to 21, with higher total and subscale scores indicating higher levels of distress.

Coping Strategies

We used the Brief COPE to assess patients’ use of coping strategies. The Brief COPE is a 28-item questionnaire that assesses 14 coping methods using two items for each method.26 In order to minimize questionnaire burden for participants, we limited our assessment to the following seven coping strategies, which we felt were most appropriate for our study population: emotional support, positive reframing, active, acceptance, self-blame, denial, and behavioral disengagement. Scores on each scale range from 2 to 8, with higher scores indicating greater use of that particular coping strategy. In order to determine the strategies used most frequently in our sample, we calculated the median scores on each item of the Brief COPE and then described the proportion of patients with a score greater than the median.8, 22, 23 We designated patients with scores above the median as ‘high’ utilizers of that particular coping strategy.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to analyze the frequencies, medians, means, and standard deviations (SDs) of the study variables. We assessed differences in high utilization of each coping strategy by patient characteristics using Fisher’s Exact Test. To examine the associations between patients’ coping strategies and their QOL and mood, we computed linear regression models adjusting for potential confounders known to be associated with the predictor of interest (coping) and the outcomes of interest (QOL and mood). Specifically, our models adjusted for patients’ age, sex, marital status, and cancer type.27, 28 We performed our statistical analyses using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

Participant Sample

From May 2011 to July 2015, we enrolled 350 of 480 eligible patients (72.9%). Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Participants (mean age, 64.9 ± SD 10.9 years) were primarily white (92.3%), and the majority were male (54.0%), married (69.7%), and had a lung cancer diagnosis (54.6%).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Participants, N=350

| Clinical Characteristics | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 64.86 (10.86) |

| ≥65 | 176 (50.3) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 189 (54.0) |

| Female | 161 (46.0) |

| Race | |

| White | 323 (92.3) |

| African American | 10 (2.9) |

| Asian | 8 (2.3) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 4 (1.1) |

| Other | 5 (1.4) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnic group | 9 (2.6) |

| Cancer Type | |

| Gastrointestinal | 159 (45.4) |

| Lung | 191 (54.6) |

| Smoking History | |

| <10 pack years | 142 (40.6) |

| ≥10 pack years | 188 (53.7) |

| Unknown | 20 (5.7) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0 | 88 (25.1) |

| 1 | 231 (66.0) |

| 2 | 31 (8.9) |

| Initial cancer therapy | |

| Chemotherapy | 278 (79.4) |

| Radiation* | 67 (19.1) |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 3 (0.9) |

| No chemotherapy or radiation | 2 (0.6) |

| Religion | |

| Catholic | 201 (57.6) |

| Protestant | 62 (17.8) |

| Jewish | 16 (4.6) |

| Muslim | 3 (0.9) |

| None | 41 (11.7) |

| Other | 26 (7.4) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Married | 244 (69.7) |

| Divorced | 35 (10.0) |

| Widowed | 35 (10.0) |

| Single | 27 (7.7) |

| Non-cohabitating relationship | 6 (1.7) |

| Other | 3 (0.9) |

| Have dependent children | 44 (12.6) |

| Education level | |

| ≤ High school | 131 (37.4) |

| > High school | 219 (62.6) |

| Income Level | |

| ≤ $50,000 | 133 (38.0) |

| >$50,000 | 189 (54.0) |

| Missing | 28 (8.0) |

| QOL | |

| FACT-G | 78.31 (15.18) |

| Mood symptoms | |

| HADS-Depression | 4.65 (4.01) |

| HADS-Anxiety | 5.31 (3.92) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; QOL, quality of life; Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G); HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

one person who received transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) as their initial cancer therapy is included within the radiation category

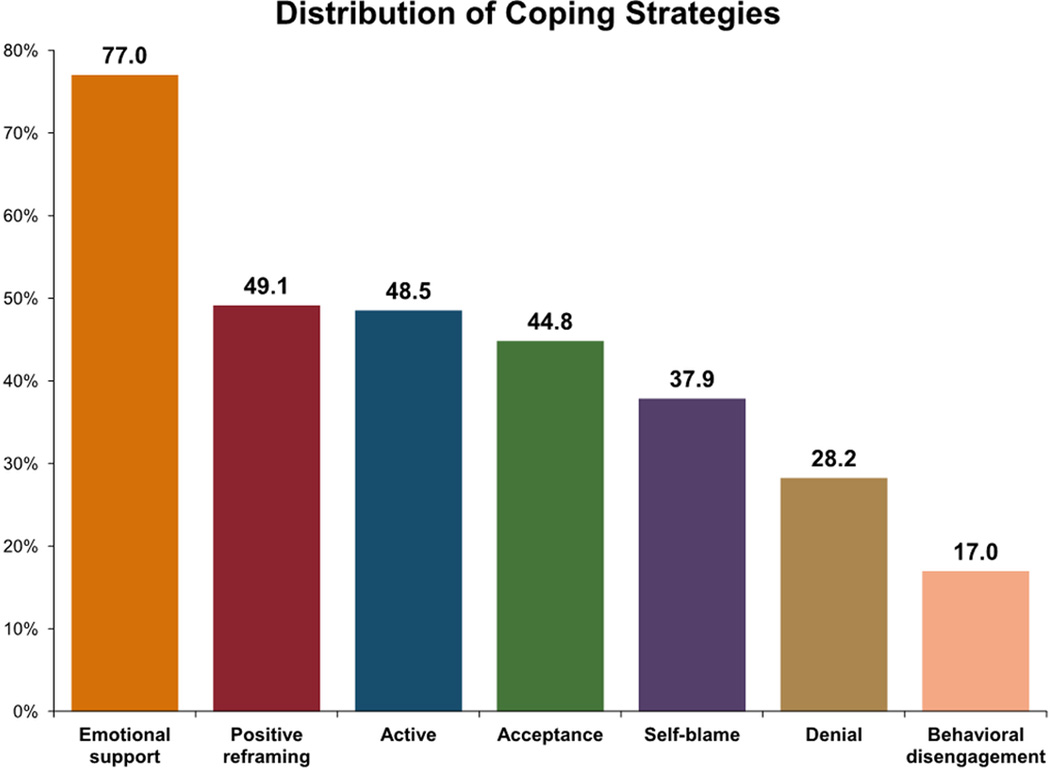

Use of Coping Strategies

Emotional support, active, and acceptance coping had the highest median scores, while behavioral disengagement, self-blame, and denial had the lowest. Figure 1 depicts the proportion of patients utilizing each coping strategy greater than the median. Most patients reported high utilization of emotional support (77.0%) coping, yet many also reported high utilization of acceptance (44.8%), self-blame (37.9%) and denial (28.2%).

Figure 1. Distribution of Coping Strategies.

Displays the proportion of patients with a score greater than the median for each coping strategy. Median scores for each coping strategy were: active, 7.0; denial, 3.0; emotional support, 8.0; behavioral disengagement, 2.0; positive reframing, 5.0; self-blame, 2.0; acceptance, 7.0.

We compared the proportion of patients reporting high utilization of each coping strategy across age (< 65 years and ≥ 65 years), sex, marital status, cancer type, religion, and smoking history. A greater proportion of younger patients (58.6% vs 39.9%, p=0.001), non-Catholics (55.9% vs 44.4%, p=0.038), and those with less than 10 pack years smoking history (56.2% vs 42.9%, p=0.017) reported high utilization of positive reframing compared to their counterparts. Additionally, a larger percentage of younger patients (43.9% vs 32.0%, p=0.027), those with lung cancer (43.1% vs 31.6%, p=0.034), and those with ≥10 pack years smoking history (44.6% vs 30.2%, p=0.008) reported high utilization of self-blame. We found no differences in the use of active, denial, emotional support, behavioral disengagement, and acceptance coping strategies across these demographic and clinical characteristics.

Associations between Coping Strategies and Quality of Life

Using linear regression, we found an association between participants’ use of emotional support, acceptance, denial, and self-blame coping strategies and their QOL (Table 2). Emotional support (β=2.646, SE=0.855, p=0.002) and acceptance (β=1.533, SE=0.540, p=0.004) coping strategies correlated with higher FACT-G scores. Conversely, denial (β=−1.970 SE=0.542, p<0.001) and self-blame (β=−2.306, SE=0.617, p<0.001) were associated with lower FACT-G scores.

Table 2.

Correlation between Coping Strategies and Quality of Life, Depression and Anxiety

| Coping Strategies | QOL | Depression | Anxiety | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | P | β | SE | P | Β | SE | P | |

| Emotional support | 2.646 | 0.855 | 0.002 | −0.555 | 0.230 | 0.016 | −0.087 | 0.222 | 0.697 |

| Positive reframing | 0.841 | 0.438 | 0.056 | −0.232 | 0.118 | 0.050 | 0.002 | 0.114 | 0.988 |

| Active | 0.483 | 0.586 | 0.410 | −0.294 | 0.158 | 0.063 | −0.135 | 0.152 | 0.375 |

| Acceptance | 1.553 | 0.540 | 0.004 | −0.376 | 0.145 | 0.010 | −0.339 | 0.140 | 0.016 |

| Self-blame | −2.306 | 0.617 | <0.001 | 0.581 | 0.166 | 0.001 | 0.662 | 0.160 | <0.001 |

| Denial | −1.970 | 0.542 | <0.001 | 0.363 | 0.146 | 0.013 | 0.606 | 0.141 | <0.001 |

| Behavioral disengagement | −1.216 | 0.962 | 0.207 | 0.227 | 0.259 | 0.380 | 0.237 | 0.250 | 0.343 |

Abbreviations: QOL, quality of life; SE, standard error.

P values derived from linear regression models adjusting for patients’ age, sex, marital status, and cancer type.

Associations between Coping Strategies and Mood

We found an association between participants’ use of emotional support, acceptance, denial, and self-blame coping strategies and their HADS-depression scores. Emotional support (β=−0.555, SE=0.230, p=0.016) and acceptance (β=−0.376, SE=0.145, p=0.010) coping strategies correlated with lower depression scores, while denial (β=0.363, SE=0.146, p=0.013) and self-blame (β=0.581, SE=0.166, p=0.001) correlated with higher depression scores. Additionally, we found an association between participants’ use of acceptance, denial, and self-blame coping strategies and their HADS-anxiety scores. Use of acceptance (β=−0.339, SE=0.140, p=0.016) coping correlated with lower anxiety scores, while denial (β=0.606, SE=0.141, p<0.001) and self-blame (β=0.662, SE=0.160, p<0.001) coping strategies correlated with higher anxiety scores.

Discussion

We investigated how patients with newly diagnosed, incurable GI and lung cancer cope with their illness and found an association between patients’ coping strategies and their QOL and mood. In this cohort, emotional support was the most frequently utilized coping strategy, yet over one-third of patients also reported high utilization of positive reframing, acceptance, active, and self blame coping. We demonstrated that emotional support and acceptance coping strategies were associated with better QOL and mood. We also found that denial and self-blame correlated with worse QOL and mood. Collectively, these findings not only underscore that patients’ coping strategies influence their physical and psychological well-being, but also indicate that certain coping behaviors may be more adaptive than others.

Our work highlights the coping strategies most highly utilized by patients with newly diagnosed, incurable cancer. A more comprehensive understanding of the most frequently utilized coping strategies in this population can be instrumental in: (1) providing psychological and supportive care services that meet their needs; (2) understanding how coping can influence patients’ approach to their medical care and decision-making; and (3) identifying frequently utilized adaptive coping behaviors that can be further nurtured to improve patients’ outcomes. Additionally, by understanding the coping strategies utilized by patients soon after their cancer diagnosis, clinicians may be prepared to better support their patients during future times of stress. Thus, our study successfully identifies the diverse, unique, and most commonly utilized ways patients with newly diagnosed, incurable cancer cope with their terminal illness, which can enable us to better support this population and ultimately improve the quality of their care.

Interestingly, we identified differential use of specific coping strategies across patient subpopulations. For example, younger patients were more likely to highly utilize positive-reframing and self-blame coping compared to older patients. Studies suggest that older adults more effectively mitigate the highs and lows associated with a cancer diagnosis, which may help explain their lower reliance on these coping strategies.29, 30 We also demonstrated that patients with a more extensive smoking history and those with a lung cancer diagnosis were more likely to report high use of self-blame, which adds to the literature suggesting that these patients experience more guilt and shame related to their cancer diagnosis.31–33 By highlighting the different coping strategies commonly utilized across specific subgroups of patients, these findings may help clinicians anticipate the needs of their patients and identify those at risk for maladaptive coping and higher psychological distress.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report that coping strategies are associated with QOL and mood in patients with newly diagnosed, incurable cancer. Importantly, these findings will inform future efforts to improve QOL and mood in this vulnerable population. By assessing patients’ coping at the time of diagnosis, we can identify those using strategies such as denial and self-blame, who are at increased risk of distress, and provide greater psychological support through early involvement of social work or psychology. Additionally, we can implement behavioral interventions that encourage patients to utilize more adaptive coping mechanisms and prevent the perpetuation of maladaptive strategies. Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that early integration of palliative care for patients with newly diagnosed, incurable cancer improves their QOL and mood,34–37 yet none have investigated the impact of early palliative care on patients’ coping strategies. Determining how early palliative care interventions influence patients’ coping strategies may shed light on one of the possible mechanisms underlying the positive outcomes seen in patients receiving these interventions. In future analyses, we will examine how the integration of palliative care early in the disease course for patients with incurable cancer can influence their use of coping strategies over time. This work may further support the importance of assessing patients’ use of coping strategies and training clinicians to tailor their care based on patients’ unique needs. Thus, this data marks the first step in understanding the relationship between patients’ coping mechanisms and other patient-reported outcomes that will help build a foundation for developing interventions to improve the experience of patients with newly diagnosed, incurable disease.

Our findings expand upon prior research suggesting that particular coping strategies may be more adaptive than others in patients with cancer.7, 9, 15–18, 38, 39 Prior studies of women with breast and gynecologic cancers demonstrated that acceptance coping was positively associated with QOL, while denial and self-blame negatively correlated with this outcome.9, 40, 41 Similarly, studies have shown that denial and self-blame coping correlated with greater psychological distress in patients with potentially curable breast and head and neck cancers.42–44 While our findings are consistent with these results, most of these studies lacked male representation and evaluated patients with curable disease at varying times in their disease course. Patients in our study all had newly diagnosed, poor prognosis, incurable cancer which is generally associated with greater emotional and psychological distress compared to patients diagnosed with curable cancers.45 Thus, our study provides valuable new insights about the relationships between coping strategies, QOL and psychological distress in a large sample of patients with newly diagnosed, incurable cancer.

Our work has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, we performed this study at a single, academic cancer center with a relatively homogenous patient sample. Therefore, our findings may not generalize to other patient populations with more racial and ethnic diversity or to patients from other geographic areas. Additionally, patients in this study were enrolled in a randomized trial of early palliative care, and these patients may differ from those who chose not to participate. Second, we did not collect information about patients’ use of other services, such as psychiatric, social work, or chaplaincy services, which may affect patients’ coping, QOL and mood.23 However, participants are less likely to have extensively received these services, as they completed baseline study measures early in their disease course. Third, our findings support an association between coping strategies and patients’ QOL and mood, but we cannot state the directionality of this relationship or if one predicts the other. Finally, this study does not provide information about unmeasured coping strategies (e.g., religious coping or substance use) or how patients’ coping strategies change throughout their illness trajectory. Future efforts to better understand the longitudinal impact of coping strategies on patients’ QOL and mood are underway, and will help further decipher the mechanisms underlying the relationships between patients’ use of coping strategies and other outcomes, including QOL and mood.

In summary, we demonstrated that patients utilize a variety of coping strategies early after their diagnosis of incurable cancer. Notably, most reported high utilization of emotional support coping, but a concerning proportion also reported high utilization of denial and self-blame coping. In addition, we found that emotional support and acceptance coping were associated with better QOL and mood, while denial and self-blame correlated with worse QOL and mood in patients newly diagnosed with incurable cancer. These findings highlight an important need to better understand how patients with incurable cancer cope with their illness, and to determine if interventions can enhance more adaptive coping behaviors. Future research should focus on developing interventions to facilitate the use of certain coping strategies while also determining the impact of these interventions on patients’ QOL, mood, and end-of-life care.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: NINR R01 NR012735 (Temel) and NCI K24 CA181253 (Temel)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Ryan Nipp, Areej El-Jawahri, Joel Fishbein, Justin Eusebio, Jamie Stagl, Emily Gallagher, Elyse Park, Vicki Jackson, William Pirl, Joseph Greer, and Jennifer Temel have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions: All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. All were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All provided final approval of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Teunissen SC, Wesker W, Kruitwagen C, de Haes HC, Voest EE, de Graeff A. Symptom prevalence in patients with incurable cancer: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbera L, Seow H, Howell D, et al. Symptom burden and performance status in a population-based cohort of ambulatory cancer patients. Cancer. 2010;116:5767–5776. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1203–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brundage MD, Davidson JR, Mackillop WJ. Trading treatment toxicity for survival in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:330–340. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirose T, Yamaoka T, Ohnishi T, et al. Patient willingness to undergo chemotherapy and thoracic radiotherapy for locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18:483–489. doi: 10.1002/pon.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reaby LL. The quality and coping patterns of women's decision-making regarding breast cancer surgery. Psychooncology. 1998;7:252–262. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199805/06)7:3<252::AID-PON309>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hack TF, Degner LF. Coping responses following breast cancer diagnosis predict psychological adjustment three years later. Psychooncology. 2004;13:235–247. doi: 10.1002/pon.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maciejewski PK, Phelps AC, Kacel EL, et al. Religious coping and behavioral disengagement: opposing influences on advance care planning and receipt of intensive care near death. Psychooncology. 2012;21:714–723. doi: 10.1002/pon.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Rothrock NE, Anderson B. Coping and quality of life among women extensively treated for gynecologic cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:132–142. doi: 10.1002/pon.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller SM. Monitoring versus blunting styles of coping with cancer influence the information patients want and need about their disease. Implications for cancer screening and management. Cancer. 1995;76:167–177. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950715)76:2<167::aid-cncr2820760203>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Philip EJ, Merluzzi TV, Zhang Z, Heitzmann CA. Depression and cancer survivorship: importance of coping self-efficacy in post-treatment survivors. Psychooncology. 2013;22:987–994. doi: 10.1002/pon.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts N, Czajkowska Z, Radiotis G, Korner A. Distress and coping strategies among patients with skin cancer. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2013;20:209–214. doi: 10.1007/s10880-012-9319-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopman P, Rijken M. Illness perceptions of cancer patients: relationships with illness characteristics and coping. Psychooncology. 2015;24:11–18. doi: 10.1002/pon.3591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lutgendorf SK, Anderson B, Ullrich P, et al. Quality of life and mood in women with gynecologic cancer: a one year prospective study. Cancer. 2002;94:131–140. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Huggins ME. The first year after breast cancer diagnosis: hope and coping strategies as predictors of adjustment. Psychooncology. 2002;11:93–102. doi: 10.1002/pon.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carver CS, Pozo C, Harris SD, et al. How coping mediates the effect of optimism on distress: a study of women with early stage breast cancer. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993;65:375–390. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dunkel-Schetter C, Feinstein LG, Taylor SE, Falke RL. Patterns of coping with cancer. Health Psychol. 1992;11:79–87. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palos GR, Mendoza TR, Liao KP, et al. Caregiver symptom burden: the risk of caring for an underserved patient with advanced cancer. Cancer. 2011;117:1070–1079. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miovic M, Block S. Psychiatric disorders in advanced cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:1665–1676. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis MP, Dreicer R, Walsh D, Lagman R, LeGrand SB. Appetite and cancer-associated anorexia: a review. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1510–1517. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:1140–1147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:445–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker PA, Baile WF, de Moor C, Cohen L. Psychosocial and demographic predictors of quality of life in a large sample of cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2003;12:183–193. doi: 10.1002/pon.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nipp RD, Greer JA, Traeger L, et al. Which patients experience improved quality of life (QOL) and mood from early palliative care (PC)? J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(suppl 31) abstr 16. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mor V, Allen S, Malin M. The psychosocial impact of cancer on older versus younger patients and their families. Cancer. 1994;74:2118–2127. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19941001)74:7+<2118::aid-cncr2820741720>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blank TO, Bellizzi KM. A gerontologic perspective on cancer and aging. Cancer. 2008;112:2569–2576. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chapple A, Ziebland S, McPherson A. Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328:1470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38111.639734.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dirkse D, Lamont L, Li Y, Simonic A, Bebb G, Giese-Davis J. Shame, guilt, and communication in lung cancer patients and their partners. Curr Oncol. 2014;21:e718–e722. doi: 10.3747/co.21.2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LoConte NK, Else-Quest NM, Eickhoff J, Hyde J, Schiller JH. Assessment of guilt and shame in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer compared with patients with breast and prostate cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2008;9:171–178. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2008.n.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:741–749. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Temel JS, Jackson VA, Billings JA, et al. Phase II study: integrated palliative care in newly diagnosed advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2377–2382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Cameron CL, et al. Emotionally expressive coping predicts psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:875–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Culver JL, Arena PL, Antoni MH, Carver CS. Coping and distress among women under treatment for early stage breast cancer: comparing African Americans, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites. Psychooncology. 2002;11:495–504. doi: 10.1002/pon.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brunault P, Champagne AL, Huguet G, et al. Major depressive disorder, personality disorders, and coping strategies are independent risk factors for lower quality of life in non-metastatic breast cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pon.3947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kershaw T, Northouse L, Kritpracha C, Schafenacker A, Mood D. Coping strategies and quality of life in women with advanced breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psychol Health. 19:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aguado Loi CX, Baldwin JA, McDermott RJ, et al. Risk factors associated with increased depressive symptoms among Latinas diagnosed with breast cancer within 5 years of survivorship. Psychooncology. 2013;22:2779–2788. doi: 10.1002/pon.3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Horney DJ, Smith HE, McGurk M, et al. Associations between quality of life, coping styles, optimism, and anxiety and depression in pretreatment patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2011;33:65–71. doi: 10.1002/hed.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kitano A, Yamauchi H, Hosaka T, et al. Psychological impact of breast cancer screening in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10147-015-0845-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vainio A, Auvinen A. Prevalence of symptoms among patients with advanced cancer: an international collaborative study. Symptom Prevalence Group. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1996;12:3–10. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(96)00042-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]