General practitioners in the United Kingdom will see about one patient with Bell's palsy every two years. Increasing evidence shows that the way the patient is managed has an important effect on outcome. Untreated Bell's palsy leaves some patients with major facial dysfunction and a reduced quality of life. Of patients with Bell's palsy registered by general practitioners between 1992 and 1996 a fifth were referred for specialist opinion, just over a third received oral steroids, and 0.6% received aciclovir.1 Improving outcomes requires coordination between specialists and general practitioners so that patients are treated during the critical first 72 hours. We outline recent developments in Bell's palsy and current best evidence in its management.

Sources and selection criteria

We canvassed specialists with an interest in acute facial palsy and incorporated the latest consensus from key publications and systematic reviews. We performed a hierarchical literature search through Medline, CINAHL, SUMSearch, bmj.com, Lancet Neurology Network, Bandolier, Health Technology Assessment, Clinical Evidence, and the Cochrane Library. Both authors are otolaryngologists with an interest in neurotology and facial palsy.

Incidence and pathophysiology

Bell's palsy accounts for almost three quarters of all acute facial palsies, with the highest incidence in the 15 to 45 year old age group (table 1).2 The annual incidence in the UK population is around 20 per 100 000, with one in 60 people being affected during their lifetime. Men and women are equally affected, although the incidence is higher in pregnant women (45 cases per 100 000).

Table 1.

Causes and incidence of acute facial palsy2

| Causes | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Bell's palsy |

72 |

| Herpes simplex virus type 1 |

84 |

| Herpes zoster virus: |

|

| Zoster sine herpete |

16 |

| Ramsay Hunt syndrome |

7 |

| Trauma |

4 |

| Tumour |

4 |

| Otitis media or cholesteatoma |

3 |

| Neonatal conditions |

6 |

| Rare and unusual conditions | 4 |

Recent developments

Bell's palsy is probably caused by herpes viruses, mainly herpes simplex virus type 1 and herpes zoster virus

Facial palsy improves after treatment with combined oral aciclovir and prednisone

Treatment of partial Bell's palsy is controversial; a few patients don't recover if left untreated

Treatment is probably more effective before 72 hours and less effective after seven days

A fifth of cases of acute facial palsy have an alternative cause that should be managed appropriately

Increasing evidence implies that the main cause of Bell's palsy is latent herpes viruses (herpes simplex virus type 1 and herpes zoster virus), which are reactivated from cranial nerve ganglia. Sensitive polymerase chain reaction techniques have isolated herpes virus DNA from the facial nerve during acute palsy.3 Inflammation of the nerve initially results in a reversible neurapraxia, but ultimately Wallerian degeneration ensues. Herpes zoster virus shows more aggressive biological behaviour than herpes simplex virus type 1 because it spreads transversely through the nerve by way of satellite cells.

Symptoms

The most alarming symptom of Bell's palsy is paresis; up to three quarters of affected patients think they have had a stroke or have an intracranial tumour. The palsy is often sudden in onset and evolves rapidly, with maximal facial weakness developing within two days. Associated symptoms may be hyperacusis, decreased production of tears, and altered taste (table 2).

Table 2.

Polyneuropathy in Bell's palsy4

| Symptoms | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Altered glossopharyngeal or trigeminal nerve sensation |

80 |

| Facial or retroauricular pain |

60 |

| Altered taste |

57 |

| Hyperacusis |

30 |

| Reduced sensation C2 dermatome |

20 |

| Vagal motor weakness |

20 |

| Decreased tearing |

17 |

| Trigeminal motor weakness | 3 |

Patients may also mention otalgia or aural fullness and facial or retroauricular pain, which is typically mild and may precede the palsy. Severe pain suggests herpes zoster virus and may precede a vesicular eruption and progression to Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Features may be consistent with a mild polyneuropathy. A slow onset progressive palsy with other cranial nerve deficits or headache raises the possibility of a neoplasm.

Examination

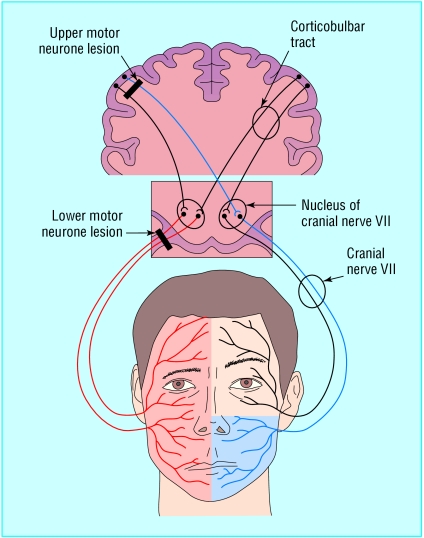

Bell's palsy causes a peripheral lower motor neurone palsy, which manifests as the unilateral impairment of movement in the facial and platysma muscles, drooping of the brow and corner of the mouth, and impaired closure of the eye and mouth. Bell's phenomenon—upward diversion of the eye on attempted closure of the lid—is seen when eye closure is incomplete.

A central upper motor neurone deficit causes weakness of the lower face only (fig 1). More complex segmental deficits may be caused by peripheral facial nerve lesions. Patients with facial palsy require careful examination of the other cranial nerve and cerebellar function. The modified House-Brackmann facial grading scale allows consistent documentation of facial palsy (see table on bmj.com).5

Fig 1.

Lesion of right upper motor neurone causes central pattern of facial weakness on left. Lesion of right lower motor neurone causes facial palsy on right. Adapted from Dresner6

Assessment of the ear should include pneumatic otoscopy and tuning fork tests. Polyposis or granulations in the ear canal may suggest cholesteatoma or malignant otitis externa. Vesicles in the conchal bowl, soft palate, or tongue suggest Ramsay Hunt syndrome (see fig A on bmj.com).

The examination should exclude masses in the head and neck. A deep lobe parotid tumour may only be identified clinically by careful examination of the oropharynx and ipsilateral tonsil to rule out asymmetry (fig 2). Erythema migrans on the limbs or trunk with a history of tick bite implies Lyme disease, which may cause facial palsy.7

Fig 2.

Woman with segmental facial palsy showing reduced elevation of right eyebrow and closure of right eye. A malignant mass was found in the right parotid gland. Reproduced with patient's permission

Investigations

Serum testing for rising antibody titres to herpes virus is not a reliable diagnostic tool for Bell's palsy. Salivary polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex virus type 1 or herpes zoster virus is more likely to confirm virus during the replicating phase, but these tests remain research tools. Serological tests for Lyme disease (IgM, IgG) are essential to exclude this disease in endemic areas, and magnetic resonance imaging has revolutionised the detection of tumours. Typically, the hearing threshold is not affected in Bell's palsy, but stapedius reflexes may be reduced or absent. Topognostic tests and electroneurography may give useful prognostic information but remain research tools.8

Zoster sine herpete

Herpes zoster virus has traditionally been associated with Ramsay Hunt syndrome, with typical cutaneous vesicles and cochleovestibular dysfunction. Vesiculation may not necessarily appear (zoster sine herpete) or may be delayed in up to half of patients. Dermatomal pain and dysaesthesia before vesiculation is termed preherpetic neuralgia and may be the only clinical indicator that herpes zoster virus is involved. Zoster sine herpete is thought to be the cause of almost a third of facial palsies previously diagnosed as idiopathic.9

Box 1: Indicators of poor prognosis in Bell's palsy

Complete facial palsy

No recovery by three weeks

Age over 60 years

Severe pain

Ramsay Hunt syndrome (herpes zoster virus)

Associated conditions—hypertension, diabetes, pregnancy

Severe degeneration of the facial nerve shown by electrophysiological testing

Bell's palsy in children

Bell's palsy is a much less common cause of facial palsy in children under 10 years of age. These children therefore merit careful review to identify an alternative cause, including acute suppurative ear disease. Lyme disease may be responsible for as many as half the cases in endemic areas.

Outcomes

Overall, Bell's palsy has a fair prognosis without treatment, with almost three quarters of patients recovering normal mimetical function and just over a tenth having minor sequelae. A sixth of patients are left with either moderate to severe weakness, contracture, hemifacial spasm, or synkinesis. Patients with a partial palsy fair better, with 94% making a full recovery. The outcome is worse when herpes zoster virus infection is involved in partial palsy. In patients who recover without treatment, major improvement occurs within three weeks in most. If recovery does not occur within this time, then it is unlikely to be seen until four to six months, when nerve regrowth and reinnervation have occurred. By six months it is clear who will have moderate to severe sequelae. Box 1 lists the poor prognostic indicators of Bell's palsy.

In facial palsies caused by herpes simplex virus or herpes zoster virus there remains a strong correlation between the peak severity of the palsy and the outcome. As yet there is no reliable investigation or test at presentation that can indicate who will make a full recovery.

Treatment

The main aims of treatment in the acute phase of Bell's palsy are to speed recovery and to prevent corneal complications. Treatment should begin immediately to inhibit viral replication and the effect on subsequent pathophysiological processes that affect the facial nerve. Psychological support is also essential, and for this reason patients may require regular follow up.

Eye care

Eye care of patients with Bell's palsy focuses on protecting the cornea from drying and abrasion due to problems with lid closure and the tearing mechanism. The patient is educated to report new findings such as pain, discharge, or change in vision. Lubricating drops should be applied hourly during the day and a simple eye ointment should be used at night.

Corticosteroids

Two recent systematic reviews concluded that Bell's palsy could be effectively treated with corticosteroids in the first seven days, providing up to a further 17% of patients with a good outcome in addition to the 80% that spontaneously improve (see also fig B on bmj.com).10,11 Other studies have shown the benefits of treatment with steroids; in one, patients with severe facial palsy showed a significant improvement after treatment within 24 hours.12,13 Recovery rates in patients treated within 72 hours were enhanced by the addition of aciclovir.14

A randomised controlled trial of patients treated with high dose parenteral steroids within 72 hours compared with placebo found a significant improvement in recovery rate and time to return to work but no statistical difference in final outcome.15 More randomised controlled trials are needed, but at least 200 patients would be required in each arm.16,17

Given the existing evidence (see bmj.com for description of grades (A) to (D)), we support the use of oral prednisone with aciclovir in patients presenting with moderate to severe facial palsy, ideally within 72 hours. Immunocompetent patients without specific contraindications are prescribed prednisone at 1 mg/kg/d (maximum 80 mg) for the first week, which is tapered over the second week.(B) Around a fifth of patients will progress from partial palsy, so these patients should also be treated.11(C)

Antiviral agents

Treatment with antivirals seems logical in Bell's palsy because of the probable involvement of herpes viruses. Aciclovir, a nucleotide analogue, interferes with herpes virus DNA polymerase and inhibits DNA replication. Because of aciclovir's relatively poor bioavailability (15% to 30%),18 newer drugs in its class are being trialled. Better bioavailability, dosing regimens, and clinical effectiveness in treating shingles have been shown with valaciclovir (prodrug of aciclovir), famciclovir (prodrug of penciclovir), and sorivudine.19

Box 2: Evolving treatments for Bell's palsy

Some evidence of effect

Methylcobalamin—an active form of vitamin B-12

Hyperbaric oxygen—may be useful in patients who show degeneration despite maximal therapy

Facial retraining—“mime therapy”

Botulinum toxin for synkinesis and hemifacial spasm

Uncertain effect

Transcutaneous electrical stimulation

Acupuncture

Current research

Multicentre, randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trials on steroid and antiviral therapy are being carried out in Sweden and France

New antivirals—for example, famciclovir, sorivudine

Vaccination against herpes zoster virus and herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2

Neurotrophic growth factors, neuroprotective agents—for example, nimodipine, glial cell derived neurotrophic factor

Additional educational resources

Book

Pensak ML. Controversies in otolaryngology. New York: Thieme, 2001: 218-31—three chapters presenting current perspectives on acute facial palsy

Key papers

Peitersen E. Bell's palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different aetiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002;549: 4-3012482166—key text on the epidemiology and outcomes of untreated Bell's palsy

Morrow MJ. Bell's palsy and herpes zoster oticus. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2000;2: 407-16—excellent review and evidence based treatment guidelines

Sweeney CJ, Gilden DH. Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71: 14911459884—relevant publication from active researchers in this subject

Internet resources

emedicine.com—has several well structured articles on Bell's palsy

Information for patients

The official patient's sourcebook on Bell's palsy: a revised and updated directory for the internet age publisher. San Diego, CA: Icon Health, 2003—several books are available to patients, which tend to present the authors' viewpoints

Patient information. Bell's palsy. J Fam Pract Feb 2003;52: 16012596708—useful information leaflet

Bell's palsy information site (www.bellspalsy.ws/links.htm)—a structured website with information about acute treatment and rehabilitation

Bell's palsy association (www.bellspalsy.org.uk/links.htm)—UK based site providing information and support for patients

Open directory project (http://dmoz.org/)—access to a huge number of links of variable quality

Aciclovir compared with prednisone

Aciclovir has been compared with prednisone.20 Prednisone has been shown to be more effective in producing good recovery at three or more months, but despite flaws in this study, we would not recommend using aciclovir (or any antiviral) without steroids unless steroids are contraindicated.19(B)

Aciclovir with prednisone

A recent systematic review found that patients treated with combined aciclovir and prednisone had a better outcome than those treated with prednisone alone.10 However, a Cochrane review at that time concluded that more studies were required.21 More recently, a study of patients with severe palsies found better recovery with combined aciclovir and prednisone than with prednisone alone. The main determinate of the difference was treatment within three days of the onset of palsy.14

A prospective case controlled study showed that patients treated with valaciclovir and prednisone (86% within 72 hours) had better recovery rates than patients treated with prednisone alone. A noticeable benefit was seen in elderly patients, a group that is often overlooked for maximal treatment.22 A study of systemic therapy found no difference between oral aciclovir with prednisone and intravenous aciclovir with prednisone.23 Systemic treatment should be considered in immunocompromised patients or for widespread zoster involving the central nervous system.

We support the use of oral aciclovir or valaciclovir with prednisone in patients presenting within a first week (ideally within 72 hours) with moderate to severe facial palsy.(B)

Treatment in children

Studies have found that children with complete facial palsies and major degeneration have poor outcomes as often as adults. However, no supportive evidence has been found for use of steroids or antivirals in children with Bell's palsy (see fig C on bmj.com).24(D)

Zoster sine herpete

Although 2000 mg/d of aciclovir would not be adequate for Ramsay Hunt syndrome with vesicles, it seems to be effective in patients with zoster sine herpete.14 On the basis of current evidence, in the absence of major pain or evidence of vesicles, this dose would be adequate with steroids for treating Bell's palsy associated with herpes zoster virus.(C)

Future research may indicate that patients with severe post auricular pain, dense palsy, or herpes zoster virus do better with higher dose antiviral therapy from the outset.(D)

Surgery

Surgical intervention decompresses the facial nerve.25 However, middle fossa craniotomy carries risks, including seizures, deafness, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid, and facial nerve injury. Hence decompression surgery for Bell's palsy is not routinely offered in the United Kingdom.(D)

Physical therapies

Several physical therapies, including massage and facial exercises, are recommended to patients, but there are few controlled clinical trials of their effectiveness.(D) Some recent evidence supports facial retraining (mime therapy) with biofeedback.26(C)

Follow up

Patients with Bell's palsy should start treatment immediately and be referred to a specialist as soon as possible. In a few cases the diagnosis may be subsequently reassigned.2 Patients should receive psychological support and eye care during follow up. Long term sequelae may be missed if patients are not monitored for a full year.

A multidisciplinary team approach (general practitioners, otolaryngologists, ophthalmologists, plastic surgeons, physiotherapists, and psychologists) is essential when there is no prospect of further recovery of facial nerve function. Synkinesis and facial spasm, common features of partially recovered deficits, can be effectively managed with subcutaneous or intramuscular injections of botulinum toxin. Facial reanimation may be possible by a combination of static and dynamic surgical techniques and may result in functional as well as cosmetic improvements. Weighting of the upper lid improves eye closure.

Supplementary Material

Further information and description of levels of evidence are on bmj.com

Further information and description of levels of evidence are on bmj.com

We thank Carol-Ann Regan for library support and Stephanie Chapman for proof reading.

Contributors: NJH conducted the literature review and wrote the initial and final drafts. GMW reviewed and contributed to the manuscript and provided overall supervision. NJH is guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Rowlands S, Hooper R, Hughes R, Burney P. The epidemiology and treatment of Bell's palsy in the UK. Eur J Neurol 2002;9: 63-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peitersen E. Bell's palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 2002;549: 4-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murakami S, Mizobuchi M, Nakashiro Y, Doi T, Hato N, Yanagihara N. Bell's palsy and herpes simplex virus: identification of viral DNA in endoneurial fluid and muscle. Ann Intern Med 1996;124: 27-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adour KK. Current concepts in neurology: diagnosis and management of facial paralysis. N Engl J Med 82;307: 348-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1985;93: 146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dresner SC. Ophthalmic management of facial nerve paralysis. Focal points. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology, Jan 2000.

- 7.Stanek G, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet 2003;362: 1639-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dobie RA. Tests of facial nerve function. In: Cummings CW et al, eds. Otolaryngology head and neck surgery. New York: Mosby, 1998: 2757-66.

- 9.Sweeney CJ, Gilden DH. Ramsay Hunt syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 2001;71: 149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grogan PM, Gronseth GS. Practice parameter: steroids, acyclovir, and surgery for Bell's palsy (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001;56: 830-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsey MJ, DerSimonian R, Holtel MR, Burgess LP. Corticosteroid treatment for idiopathic facial nerve paralysis: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope 2000;110: 335-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williamson IG, Whelan TR. The clinical problem of Bell's palsy: is treatment with steroids effective? Br J Gen Pract 1996;46: 743-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shafshak TS, Essa AY, Bakey FA. The possible contributing factors for the success of steroid therapy in Bell's palsy: a clinical and electrophysiological study. J Laryngol Otol 1994;108: 940-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hato N, Matsumoto S, Kisaki H, Takahashi H, Wakisaka H, Honda N, et al. Efficacy of early treatment of Bell's palsy with oral acyclovir and prednisolone. Otol Neurotol 2003;24: 948-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lagalla G, Logullo F, Di Bella P, Provinciali L, Ceravolo MG. Influence of early high-dose steroid treatment on Bell's palsy evolution. Neurol Sci 2002;23: 107-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salinas RA, Alvarez G, Alvarez MI, Ferreira J. Corticosteroids for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(1): CD001942. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Burgess LP, Yim DW, Lepore ML. Bell's palsy: the steroid controversy revisited. Laryngoscope 1984;94: 1472-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Miranda P, Blum MR. Pharmacokinetics of acyclovir after intravenous and oral administration. J Antimicrob Chemother 1983;12(suppl B): 29-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snoeck R, Andrei G, De Clercq E. Current pharmacological approaches to the therapy of varicella zoster virus infections: a guide to treatment. Drugs 1999;57: 187-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Diego JI, Prim MP, De Sarria MJ, Madero R, Gavilan J. Idiopathic facial paralysis: a randomized, prospective, and controlled study using single-dose prednisone versus acyclovir three times daily. Laryngoscope 1998;108: 573-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sipe J, Dunn L. Aciclovir for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001;(4): CD001869. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Axelsson S, Lindberg S, Stjernquist-Desatnik A. Outcome of treatment with valacyclovir and prednisone in patients with Bell's palsy. Ann Oto, Rhinol Laryngol 2003;112: 197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murakami S, Hato N, Horiuchi J, Honda N, Gyo K, Yanagihara N. Treatment of Ramsay Hunt syndrome with acyclovir-prednisone: significance of early diagnosis and treatment. Ann Neurol 1997;41: 353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salman MS, MacGregor DL. Should children with Bell's palsy be treated with corticosteroids? A systematic review. J Child Neurol 2001;16: 565-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisch U. Surgery for Bell's palsy. Arch Otolaryngol 1981;107: 1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beurskens CH, Heymans PG. Positive effects of mime therapy on sequelae of facial paralysis: stiffness, lip mobility, and social and physical aspects of facial disability. Otol Neurol 2003;24: 677-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.