Sexuality and infertility

Infertility may interact with a couple's or individual's sexuality and sexual expression in two main ways. Sexual problems may be caused or exacerbated by the diagnosis, investigation, and management of infertility (or subfertility) or they may be a contributory factor in childlessness. Any examination of a couple's difficulty in conceiving must include overt and clear questioning about their sexual activity.

Responses to infertility

In response to being unable to conceive, many people feel emotions such as anger, panic, despair, and grief, and these may affect sexual activity. The stress of infertility and its treatment may also cause sexual difficulties for both men and women.

Intercourse may be avoided, with patterns of behaviour established so that one or other partner is not reminded of the fertility problem. Post-coital tests or repeated need to provide semen samples may result in a man feeling under pressure to perform, which can adversely affect his erectile or ejaculatory ability. For some men, one or two failures during intercourse begin a vicious circle of fear of failure, with anxiety leading to further failures. Partners may also develop arousal difficulties because of anxiety or distress. Some people feel that their partner wants them only when there is a chance of conception, and sexual activity can then become a battleground for issues of power and control.

Such stresses conspire to alienate couples from the recreational aspects of sexual expression and focus them, often obsessively, on the procreative aspect of sexual intercourse.

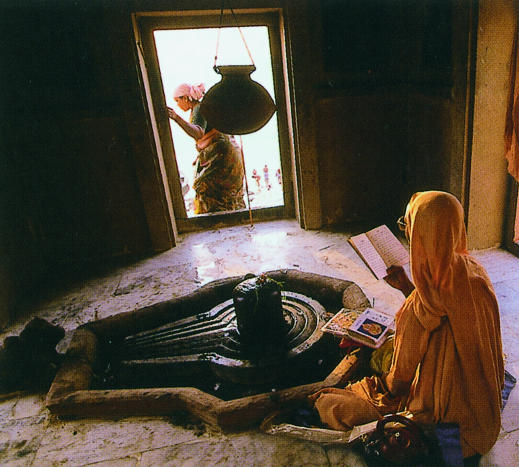

Figure 1.

Prayers being read before a lingham, the phallic symbol of Shiva, Hindu god of fertility. Fertility has always been vitally important in human society, and emotional reactions to infertility may affect sexual activity

Sexual problems that result in infertility

Childlessness may be the result of an existing sexual dysfunction. One study of infertile couples found that 5% had a history of sexual problems.

Table 1.

Useful questions to elicit information (taken from Read, 1995)

| • How have your fertility problems affected your relationship, including your sexual relationship? |

| • Has anything changed in your sexual relationship since you have been trying to conceive? |

| • How would you describe your sexual activity? |

| • How often do you have penetrative (that is, penis in vagina) sex? |

To avoid waste of time and resources, patients must be given the opportunity to discuss their previous pattern of sexual functioning to see if it has changed because of their fertility problems. It seems inexcusable that people can have months or years of invasive and expensive treatment when simple questions about their sexual lives may elicit information that could spare them the ordeal. Infertility examinations should include an evaluation of couples' sexual behaviour, with special reference to frequency and timing of coitus.

Two further categories of sexual dysfunction need to be borne in mind. The first is retrograde ejaculation, in which the ejaculate is expelled back into the bladder rather than externally. This can be checked by examining a post-ejaculatory urine sample for sperm. Men with this condition experience “dry” orgasm—they feel the sensation of muscular action and orgasm but do not produce an ejaculate. This is a fairly common presentation in fertility units and can be managed medically by centrifuging the urine to collect the sperm.

Table 2.

Sexual problems during or after pregnancy

| Female problems |

| • Loss of libido associated with, for example, tiredness and negative body image |

| • Anorgasmia associated with lack of arousal or pain |

| • Vaginismus associated with pain or trauma from delivery |

| Male problems |

| • Lack of desire |

| • Erectile dysfunction associated with fears raised by watching the delivery, causing pain on intercourse, or fatherhood |

| • Premature ejaculation associated with fears raised by watching the delivery, causing pain on intercourse, or fatherhood |

The second point that should be considered is whether the sperm are being introduced into the vagina. This can mean talking in clear terms to the couple about the nature of their sexual activity. Some couples engage in anal intercourse, umbilical sex, or manual stimulation alone and naively consider that this should result in pregnancy.

This article is adapted from the second edition of the ABC of Sexual Health, which will be published later this year

Sexual difficulties in pregnancy

Pregnancy is a transition from one physical state to another. In the case of a first pregnancy, it is a transition from one state of being to another—from being a couple to being a family, from being a person in a relationship with another to motherhood or fatherhood. As with any transition, a sense of loss is felt as well as the excitement of entering another phase of life's experience.

Figure 2.

It is important to remember that pregnancy is not always met with joy and that, even if a baby is planned and wanted, some ambivalence may be present. This response will also be affected by myths about pregnancy, taboos about sexual activity during pregnancy, fears about the baby and delivery, changes in the relationship with the partner, and beliefs about the roles of motherhood and fatherhood. The woman's changing body shape may cause distress and a sense of unattractiveness.

Sexual difficulties may be essentially psychological in origin, occurring as an emotional response to the changed or changing state, or may be a direct physical response to the pregnancy. One, of course, does not exclude the other, and a mixed aetiology is common. A combination of sexual problems may be present, and they may also occur in the period after delivery. A careful history should be taken to ascertain what is causing any difficulties.

Table 3.

Points to consider when taking a history

| • Assessment of the relationship, sexually and otherwise, and the patient's support network |

| • Whether the pregnancy was planned |

| • Previous outcomes of pregnancies (such as miscarriage or termination) |

| • Previous deliveries—type and presence of trauma |

| • Current children's health |

| • Contraception—past and current use and plans for the future |

Psychological factors

When pregnancy is the result of infertility treatment or a woman has a history of repeated miscarriages, fetal abnormality, or neonatal death, high levels of anxiety may be present, with repeated requests for reassurance or perhaps demands for scans or examinations. Apart from general anxiety, the woman may have specific concerns about body image, delivery, motherhood, changes to the couple's relationship, miscarriage, lack of self esteem, sexual guilt, and tiredness.

Table 4.

Physical factors associated with pregnancy that can reduce sexual activity (data from Reamy and White, 1985)

| • Tiredness |

| • Backache |

| • Dyspareunia |

| Pelvic vasocongestion |

| Vaginal congestion with reduced lubrication |

| Subluxation of pubic symphysis and sacroiliac joints |

| Retroverted uterus, particularly in first weeks of pregnancy |

| Weight of partner on uterus during intercourse in late pregnancy |

| • Deep engagement of fetal head |

| • Infection with Candida or Trichomonas |

| • Haemorrhoids |

| • Urinary tract infections |

| • Stress incontinence |

| • Vulval varicose veins |

Myths about intercourse during pregnancy include the fear it may cause miscarriage, premature labour, or fetal damage. Savage and Reader found no significant increase in fetal problems in women who continued to be sexually active throughout pregnancy. They noted that 27% of these women had uterine contractions after orgasm that sometimes were painful. Those who experienced painful contractions were less likely to have sexual intercourse often, if at all.

Obvious indications for abstaining from intercourse during pregnancy do exist, however. These include:

Table 5.

Sexual problems during or after pregnancy

| Female problems |

| • Loss of libido associated with, for example, tiredness and negative body image |

| • Anorgasmia associated with lack of arousal or pain |

| • Vaginismus associated with pain or trauma from delivery |

| Male problems |

| • Lack of desire |

| • Erectile dysfunction associated with fears raised by watching the delivery, causing pain on intercourse, or fatherhood |

| • Premature ejaculation associated with fears raised by watching the delivery, causing pain on intercourse, or fatherhood |

Vaginal bleeding

Placenta praevia

Premature dilatation of the cervix

Rupture of the membranes

History of premature delivery

Multiple pregnancy.

Sexuality and ageing

Bancroft reported a widespread tendency to assume that elderly people are too old for sexual activity and that the sexuality of men and women declines with advancing years. This decline depends on three main factors: the level of sexual activity throughout a person's lifetime, their physical health, and their psychological health

Sexuality throughout life

People who have been frequently sexually active throughout their life will show a lower rate of decline in activity as they age than those who have been less sexually active. Most older people who remain sexually active get high enjoyment from sex, and, in a summary of studies on sex and ageing, Kaplan concluded that most physically healthy men and women remain regularly sexually active into their ninth decade. Sexual activity could include solo and mutual masturbation, oral sex, and penetrative intercourse.

Older people may have just as wide a range of sexual interests and preferences as younger people

Dementia is not a normal consequence of ageing, although the prevalence of moderate to severe dementia is 1.4% in those aged 60-69 years, 4.1% in those aged 70-79 years, and 13% in those aged 80-84 years. Most cases will be in women, who have a longer life expectancy and are more likely to be on their own or in residential care. Affected men tend to have a home carer, usually a spouse. These factors have implications for intimacy and sexuality.

Table 6.

Resources for patients

| • The British Association for Sexual and Relationship Therapy, PO Box 13686, London SW20 9ZH |

| • Impotence Association Helpline 020 8767 7791 |

Depression is a common feature of ageing in men and women. Sexual problems may occur with a depressive illness or be a complication of its treatment. Newer antidepressants may cause sexual dysfunction, including loss of desire and anorgasmia, in both sexes. The sexual problems may aggravate existing depression.

Table 7.

Proportion of older men and women who are sexually active and find it enjoyable (data from Brecher 1984)

|

Age group (years)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| People | 50-59 | 60-69 | 70-79 |

| Sexually active | |||

| All women (n = 1844) | 93 | 81 | 65 |

| Married (n = 1245) | 95 | 89 | 81 |

| Unmarried (n = 512) | 98 | 63 | 50 |

| All men (n = 2402) | 98 | 91 | 79 |

| Married (n = 1895) | 98 | 93 | 81 |

| Unmarried (n = 414) | 95 | 85 | 75 |

|

Sex highly enjoyable (% of sexually active people)

|

|

||

| Women | 71 | 65 | 61 |

| Men | 90 | 86 | 75 |

Physical health

Any condition or illness can have an affect sexual function. For example, a woman with severe arthritis may have problems using her hands to pleasure herself or her partner or finding a sexual position that minimises the pain. Careful placing of pillows may help with positioning.

Patients may find it difficult to raise subjects such as managing incontinence when in sexual contact with another person and in solo masturbation, and the doctor will need great sensitivity to uncover such concerns.

Table 8.

Health factors that inhibit sexual activity in elderly people

| Physical factors | Psychological health |

|---|---|

| • Stress incontinence | • Sense of unattractiveness |

| • Diminishing mobility | • Facing mortality: depression, bereavement, and grief reactions |

| • Decreasing muscle tone | |

| • Uterine prolapse | |

| • Skin tone and sensitivity | • Loss of partner or friends |

| • Diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular problems | • Lack of contact with others and loneliness |

| • Chronic conditions such as arthritis |

The use of appropriate creams to help with vaginal soreness—such as oestrogen cream (if the woman is not already taking hormone replacement therapy), KY Jelly, Senselle, or an aromatic oil such as sweet almond or peach kernel oil (but not to be used with latex contraceptives, which perish)—may enable a woman (and her partner) to enjoy sexual activity much more fully. A doctor giving patients “permission” to use vibrators to help with access to genital areas and stimulation is often helpful.

Figure 3.

Older women are often expected to be celibate (Detail of Madame Bonnatt, the artist's mother (1893) by Leon Bonnat)

Psychological health

Myths and beliefs about sexual attractiveness and what it is may affect older women and contribute to low self esteem and possibly depression. A woman who has been widowed may find it difficult to find a new partner because of the higher ratio of women to men in older age groups. Older people may be embarrassed or ashamed of having sexual needs “at their age,” and they may feel fear and guilt about indulging in sexual behaviour after having been in a long term relationship—this is, in effect, a form of performance anxiety. For women especially, there also may be family expectations of celibacy that may be difficult to counter and social expectations that older people are no longer sexual.

The photograph of a Shiva lingam is reproduced with permission of the Hutchinson Library. The cartoon “I've changed my mind” is reproduced with permission of Jacky Fleming from Be a Bloody Train Driver. The painting by Bonnat is reproduced with permission of Lauros-Giraudon and the Bridgeman Art Library. Competing interests: None declared.

The ABC of Sexual Health is edited by John Tomlinson, specialist in sexual health, Winchester, john@jptomlinson.com

Further reading and resources

- • Read J. Counselling for fertility problems. London: Sage, 1995: 104.

- • Reamy KJ, White SE. Dyspareunia in pregnancy. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 1985;4: 263. [Google Scholar]

- • Adler N. Foreword. In: Stanton AL, Dunken-Schetter C, eds. Infertility. Perspectives from stress and coping research. New York: Plenum Publishing, 1991.

- • Guano-Trujillo B, Higgins P. Sexual intercourse and pregnancy. Health Care Wom Int 1987;5: 339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Savage W, Reader F. Sexual activity during pregnancy. Midwife Health Visitor Community Nurse 1984;20: 398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Mills JL, Harlap S, Harley EE. Should coitus late in pregnancy be discouraged? Lancet 1981;ii: 136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- • Bancroft J. Human sexuality and its problems. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1989: 282-5.

- • Brecher EM. Love, sex and ageing. Consumer's Union report. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1984.

- • Kaplan HS. Injection treatment for older patients. In: Wagner G, Kaplan HS, eds. The new injection treatment for impotence. New York: Brunner, Mazel, 1993: 142.

- • Baikie E. The impact of dementia on marital relationships. Sex Relation Ther 2002;17: 289-9. [Google Scholar]

- • PesceV, Seidman SN, Roose SP. Depression, antidepressants and sexual functioning in men. Sex Relation Ther 2002;17: 282-7. [Google Scholar]