Abstract

Aim

Gynecomastia is a common finding in male population of all ages. The aim of our study was to present our experience and goals in surgical treatment of gynecomastia.

Patients and Methods

Clinical records of patients affected by gynecomastia referred to our Department of Surgery between September 2008 and January 2015 were analyzed. 50 patients were included in this study.

Results

Gynecomastia was monolateral in 12 patients (24%) and bilateral in 38 (76%); idiopathic in 41 patients (82%) and secondary in 9 (18%). 39 patients (78%) underwent surgical operation under general anaesthesia, 11 (22%) under local anaesthesia. 3 patients (6%) presented recurrent disease. Webster technique was performed in 28 patients (56%), Davidson technique in 16 patients (32%); in 2 patients (4%) Pitanguy technique was performed and in 4 patients (8%) a mixed surgical technique was performed. Mean surgical time was 80.72±35.14 minutes, median postoperative stay was 1.46±0.88 days. 2 patients (4%) operated using Davidson technique developed a hematoma, 1 patient (2%) operated with the same technique developed hypertrophic scar.

Conclusions

Several surgical techniques are described for surgical correction of gynecomastia. If performed by skilled general surgeons surgical treatment of gynecomastia is safe and permits to reach satisfactory aesthetic results.

Keywords: Gynecomastia, Breast, Surgery

Introduction

Gynecomastia is a benign condition characterized by enlargement of the male breast due to proliferation of the glandular tissue. This condition may be unilateral or bilateral, symmetric or asymmetric. Gynecomastia is thought to result from a number of mechanism including an imbalance in the testosterone to estrogen ratio as well as an increase in human chorionic gonadotropin receptors and luteinizing hormone receptors in male breast tissue (1, 2). Gynecomastia is a common condition: about 60% of all boys develop transient pubertal breast enlargement (3), and 30–70% of adult men have palpable breast tissue, with the higher prevalence being seen in older men and those with concurrent medical illnesses (4, 5). The goals of surgical treatment of gynecomastia should include a pleasant chest shape with limited scar extension. The surgical treatment of gynecomastia is not restricted to one discipline but is performed by plastic, general and pediatric surgeons, with many differences in practice, and this may be due to different treatment philosophies or differences in patients referred to the different surgical disciplines (6). We present our experience in surgical treatment of gynecomastia as general surgeons.

Patients and methods

The clinical records of patients who underwent surgical treatment of gynecomastia between September 2008 and January 2015 in our Department of Surgery at the University of Cagliari were analyzed (Simon classification I–II B). 50 patients were included in this study. Prior to surgery, we took accurate medical history of patients and we performed a full physical examination. Dosage of serum testosterone, estradiol, prolactin, chorionic gonadotropin, mammary and testicular ultrasound and endocrinological assessment were performed for excluding underlying endocrinopathies, metabolic disorders, testicular cancer, and for identify risk factors for gynecomastia. Surgical techniques used to correct gynecomastia were subcutaneous mastectomy using Webster method with periareolar incision or Pitanguy technique with transareolar incision if skin redundancy was absent and Davidson concentric circles technique if skin reduction was necessary. During the surgery the first operator established if a suction drain was necessary or not on the basis of extent of dissection. Each mammary specimen was examined to achieve histopathological diagnosis.

Results

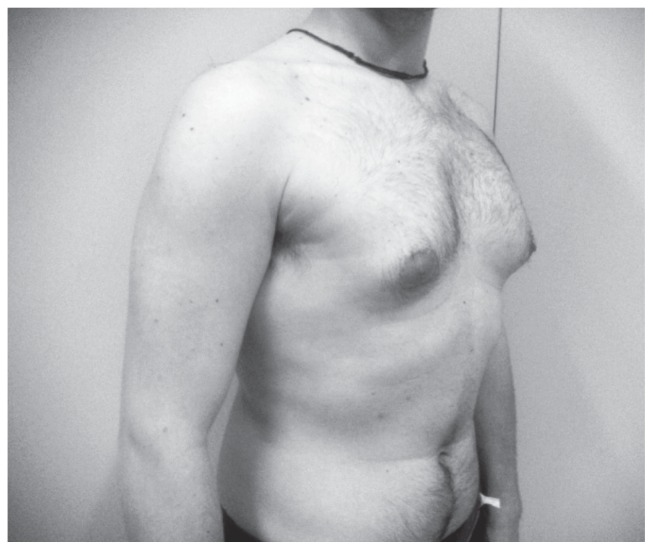

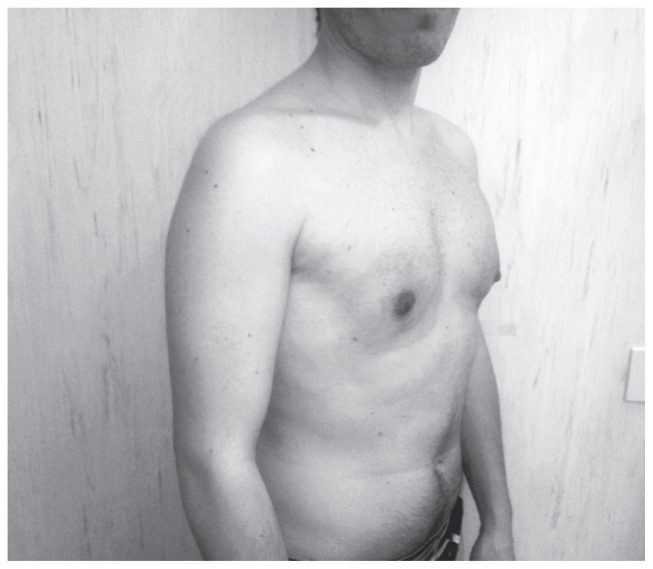

50 patients were included in our study. As reported in Table 1, gynecomastia was monolateral in 12 patients (24%) and bilateral in 38 patients (76%). Median age was 28.6 ± 11.3 years. Not a single patient exhibited family history of gynecomastia. 9 patients (18%) presented risk factors for gynecomastia as drug abuse (cannabis, cocaine), antiepileptic drugs, anabolic steroids, anti-androgens drugs, history of prolactinoma or hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism; in all other cases gynecomastia was idiopathic (82%). 3 patients (6%) exhibited recurrent gynecomastia (2 patients formerly operated for bilateral gynecomastia and 1 patient formerly operated for monolateral gynecomastia). 39 patients (78%) underwent surgical operation under general anaesthesia, in 11 patients (22%) a local anaesthesia with sedation was performed. Webster technique (Figures 1, 2) was performed for the correction of gynecomastia in 28 patients (56%): 10 patients presented monolateral disease, 18 patients presented bilateral disease. Davidson technique (Figures 3, 4) was performed in 16 patients (32%): 2 patients presented monolateral disease, 14 patients presented bilateral disease. In 2 patients (4%) with bilateral gynecomastia surgical operation was performed using Pitanguy technique. In 4 patients (8%) affected by bilateral gynecomastia a mixed surgical technique was performed (Webster method + Davidson method in 3 patients, Webster method + liposuction in 1 patient). In 33 patients (66%) suction drainages were placed: suction drainages were used mainly in patients operated with Davidson technique or mixed technique compared to patients operated with Webster method (93.7% vs 83.3% vs 46.4%, p=0.006). As reported in Table 2, mean surgical time was 80.72±35.14 minutes (64.6±35.3 min for Webster Technique, 107.6±35.04 min for Davidson technique, 112.5±10.6 min for Pitanguy technique and 72.5±33.39 min for mixed surgical technique, p<0.001). 2 patients (4%) operated using Davidson technique developed a hematoma which did not require surgical treatment (p=0.2) and 1 patient (2%) operated using the same technique developed hypertrophic scar (p=0.5). Median postoperative stay was 1.46±0.88 days (1.21±0.89 days for Webster technique, 2±0.89 days for Davidson Technique, 1 day for Pitanguy technique and 1±0.56 days for mixed surgical technique, p=0.02). In every case histopathological examination excluded diagnosis of malignancy. Patients were contacted by phone in order to communicate their level of aesthetic satisfaction: 16 patients (32%) were unreachable; 73.5% of patients reached on the phone expressed satisfaction with final aesthetic result, 26.5% were unsatisfied because of breast asymmetry or hypertrophic scar. There was no significant differences between the techniques in the patient’s satisfaction.

Table 1.

DEMOGRAPHIC AND ETIOPATHOGENETIC DATA, SURGICAL TECHNIQUE.

| n=50 | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.6 ± 11.3 |

| Monolateral gynecomastia | 12 (24%) |

| Bilateral gynecomastia | 38 (76%) |

| Idiopathic gynecomastia | 41 (82%) |

| Secondary gynecomastia | 9 (18%) |

| Recurrent disease | 3 (6%) |

| Webster technique | 28 (56%) |

| Davidson technique | 16 (32%) |

| Pitanguy technique | 2 (4%) |

| Mixed technique | 4 (8%) |

Figure 1.

Webster technique: preoperative image.

Figure 2.

Webster technique: postoperative image.

Figure 3.

Davidson technique: preoperative image.

Figure 4.

Davidson technique: postoperative image.

Table 2.

SURGICAL PROCEDURE: SURGICAL TIME, MEDIAN POSTOPERATIVE STAY AND POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS.

| Webster technique (n=28) | Davidson technique (n=16) | Pitanguy technique (n=2) | Mixed technique (n=4) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical time (min) | 64.6±35.3 | 107.6±35.04 | 112.5±10.6 | 72.5±33.39 | <0.001 |

| postoperative stay (days) | 1.21±0.89 | 2±0.89 | 1 | 1±0.56 | 0.02 |

| Hematoma | 0% | 2 (4%) | 0% | 0% | 0.2 |

| Hypertrophic scar | 0% | 1 (2%) | 0% | 0% | 0.5 |

| Wound infection | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Wound dehiscence | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Necrosis of nipple-areolar complex | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Discussion

Gynecomastia is a benign clinical condition that can occur in men of all ages, characterized by enlargement of the male breast, due to proliferation of glandular tissue. This condition differs from pseudogynecomastia (fatty breasts), which usually occurs in obese men, due to increased local fat deposition without glandular enlargement (7). Gynecomastia is a common finding: about half of all men demonstrate histological evidence of gynecomastia at autopsy (8). Gynecomastia can be seen as part of the normal physiological development in the newborn, adolescent and elderly (9, 10), or it can also be a result of multiple conditions as chronic diseases, neoplasia and drugs (11); most cases of gynecomastia are caused by an hormonal imbalance between estrogens and androgens, with estrogen-induced stimulation predominating (12, 13), and this may occur with increased estrogen action, decreased androgen action or a combination of the two mechanisms. The majority of men affected by gynecomastia are asymptomatic, while those referred to the specialist present persistently tender breasts, palpable lump or unsatisfactory body image (14) with important psychological repercussions. Breast development is considered a female trait and it can produce a sense of spoiled identity in men with breast disease and the timing of the onset of gynecomastia is very important: the greatest psychological impact occurs with onset in adolescence as compared with senescence or young childhood (15). Medical history and physical examination are the main components of the evaluation of patients affected by gynecomastia and no further investigation is necessary in case of age-appropriate findings. If the physical examination reveals signs suggestive of an underlying disorder, blood tests to asses serum levels of LH, FSH, estradiol, testosterone, prolactin, dehydroepiandrosterone and human chorionic gonadotropin may be useful (16, 17). Sonography is widely used in case of breast disease: typical findings in case of gynecomastia include hypoechoic retroareolar masses (nodular, poorly defined or flame-shaped), with increased anteroposterior depth at the nipple (18). Mammography is used in case of suspicion of cancer, with sensivity of 90% and specificity of 92% (19). Our accurate preoperative assessment (medical history, physical examination, ultrasound and hormonal profile) allowed us to exclude from surgery patients affected by secondary gynecomastia. Several factors can suggest the correct therapeutic approach to patients affected by gynecomastia. Asymptomatic men with long-standing disease do not require treatment if appropriate work-up does not reveal any underlying disease: reassurance and periodic follow-up visits are recommended (every 3–6 months), given that the condition is usually self-limiting (20). When breast enlargement is caused by an underlying hormonal disorder, his treatment is generally sufficient to cause regression of gynecomastia (7). If gynecomastia either persists or becomes more severe and symptomatic with reduced quality of life (pain, unsatisfactory body image with psychological distress), pharmacological and surgical treatment should be considered, especially if the patient is compliant (21). Medical treatment of gynecomastia try to correct estrogen-androgen imbalance by different pathways and can be useful if performed during the early proliferative phase without stromal hyalinization and fibrosis. Medical treatment is actually controversial: there is no consensus regarding the drug of choice and the optimal duration of treatment, furthermore literature data on efficacy of medical treatment is limited to small case series and case reports without control groups (22–24). Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for gynecomastia. Several surgical techniques have been described from Paulas Aegineta’s reduction mammoplasty through a lunate incision below the breast (625–690 AD) (25) to modern standard suction-assisted lipectomy (SAL) and ultrasound-assisted liposuction (UAL) (26), pull-through technique (27) alone or in association with UAL (28) or power-assisted liposuction (PAL) (29). Different surgical options share the same goals of restoring a pleasant chest shape with limited scar extension and the choice of surgeon depends on the severity of breast enlargement, the presence of skin excess and surgeon and patient preference (7). On the basis of our experience we can affirm that goals of surgical treatment for gynecomastia can be achieved using few reliable techniques: Webster technique with inferior periareolar approach, Pitanguy technique with transareolar approach and Davidson concentric circles technique. We performed Webster and Pitanguy techniques in patients affected by Simon’s grade I–II A gynecomastia (minor or moderate breast enlargement with no skin redundancy), whereas in patients affected by Simon’s grade II B gynecomastia (moderate breast enlargement with minor skin redundancy) we performed Davidson technique in order to remove excess skin. In the latter technique drains were used more frequently and the average duration of surgery and hospital stay were longer. These surgical techniques have enabled us to remove excess glandular tissue with limited injury of mammary region and low incidence of local complications. We had only minor complications: we observed a hematoma in 2 patients (4%) who underwent adenomammectomy using Davidson technique and 1 case of hypertrophic scar in 1 patient (2%) who underwent surgical operation with the same technique (these data did not reach statistical significance); we did not observe complications as wound infection, necrosis of nipple-areolar complex or wound dehiscence. Postoperative course of our patients was regular with rapid discharge (median postoperative stay was 1.46±0.88 days, longer in the cases of Davidson’s technique).

Men affected by gynecomastia are not considered at high risk for breast cancer (30); Klinefelter syndrome is the only condition which presents high risk of cancer, with a 50-fold higher risk that among men in the general population (31, 32), however some risk factors for gynecomastia, such as estrogen use or androgen deficiency, also are related to male breast cancer (33–35); on that basis, we performed routine histopathological analysis of all mammary specimens in order to exclude malignancy. Also it does not seem to be any relationship with other rare diseases of the male breast (36, 37). Given that the biggest problem of patients affected by gynecomastia of all grades generally is unsatisfactory body image, assessment of patient satisfaction with final aesthetic result is fundamental: 73.5% of our patients expressed full satisfaction with final results; breast asymmetry and hypertrophic scars represented main causes of patient dissatisfaction. There was no significant differences between the techniques in the patient’s satisfaction.

Conclusions

Gynecomastia is a common finding in male population and this condition can be self-limiting. In case of persistence and correlated symptomatology responsible for reduced quality of life treatment should be performed. Surgical correction is more effective than medical therapy. Several surgical techniques are described for correcting gynecomastia. If performed by experienced general surgeons using few validated techniques, surgical treatment of gynecomastia is safe and permits to reach satisfactory aesthetic results with minimal complications.

References

- 1.Hands LJ, Greenall MJ. Gynaecomastia. Br J Surg. 1991;78:907–11. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordt CA, DiVasta AD. Gynecomastia in adolescents. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:375–82. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328306a07c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nydick, Bustos J, Dale JH, Jr, Rawson RW. Gynecomastia in adolescent boys. JAMA. 1961;178:449–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040440001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bannayan GA, Hajdu SI. Gynecomastia: clinicopathologic study of 351 cases. AM J Clin Pathol. 1992;57:431–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/57.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson HE. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:795–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010023031405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lapid O, Jolink F. Surgical management of gynaecomastia: 20 years experience. Scand J Surg. 2013;103:41–5. doi: 10.1177/1457496913496359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemaine V, Cayci C, Simmons PS, Petty P. Gynecomastia in adolescent males. Semin Plast Surg. 2013;27:56–61. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1347166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams MJ. Gynecomastia: its incidence, recognition and host characterization in 447 autopsy cases. Am J Med. 1963;34:103–12. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(63)90044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gikas P, Mokbel K. Management of gynecomastia: an update. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61:1209–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:490–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199302183280708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creyghton WM, Custers M. Gynecomastia: is one cause enough? Neth J Med. 2004;62:257–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathur R, Braunstein GD. Gynecomastia: pathomecanisms and treatment strategies. Horm Res. 1997;48:95–102. doi: 10.1159/000185497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narula HS, Carlson HE. Gynecomastia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2007;36:497–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Allak A, Govindarajulu S, Shere M, Ibrahim N, Sahu AK, Cawthorn SJ. Gynecomastia: a decade of experience. Surgeon. 2011:255–8. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2010.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schonfeld WA. Gynecomastia in adolescence: effect on body image and personality adaptation. Psychosom Med. 1962;4:379–89. doi: 10.1097/00006842-196200700-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bembo SA, Carlson HE. Gynecomastia: its features, and when and how to treat it. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71(6):511–7. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.71.6.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma NS, Geffner ME. Gynecomastia in prepubertal and pubertal men. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20(4):465–70. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328305e415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dialani V, Baum J, Mehta TS. Sonographic features of gynecomastia. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29(4):539–47. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hines SL, Tan WW, Yasrebi M, DePeri ER, Perez EA. The role of mammography in male patients with breast symptoms. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(3):297–300. doi: 10.4065/82.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones DJ, Holt SD, Surtees P, Davison DJ, Coptcoat MJ. A comparison of danazol and placebo in the treatment of adult idiopathic gynaecomastia: results of a prospective study in 55 patients. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1990;72(5):296–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson RE, Murad MH. Gynecomastia: pathophysiology, evaluation and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(11):1010–5. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)60671-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maidment SL. Question 2. Which medications effectively reduce pubertal gynaecomastia? Arch Dis Child. 2010;95(3):237–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.2009.176768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petty PM, Solomon M, Buchel EW, Tran NV. Gynecomastia: evolving paradigm of management and comparison of techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(5):1301–8. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181d62962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Derman O, Kanbur NO, Tokur TE. The effect of tamoxifen on sex hormone binding globulin in adolescents with pubertal gynecomastia. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2004;17(8):1115–9. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2004.17.8.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fruhstorfer BH, Malata CM. A systematic approach to the surgical treatment of gynecomastia. Br J Plast Surg. 2003;56(3):237–246. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(03)00111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohrich RJ, Ha RY, Kenkel JM, Adams WP., Jr Classification and management of gynecomastia: defining the role of ultrasound-assisted liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(2):909–23. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000042146.40379.25. discussion 924–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morselli PG. Pull-through: a new technique for breast reduction in gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97(2):450–4. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199602000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond DC, Arnold JF, Simon AM, Capraro PA. Combined use of ultrasonic liposuction with the pull-through technique for the treatment of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(3):891–5. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000072254.75067.F7. discussion 896–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lista F, Ahmad J. Power-assisted liposuction and the pull-through technique for the treatment of gynecomastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(3):740–7. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000299907.04502.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olsson H, Bladstrom A, Alm P. Male gynecomastia and risk for malignant tumours-a cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2002;2:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hultborn R, Hanson C, Köpf I, Verbiené I, Warnhammar E, Weimarck A. Prevalence of Klinefelter’s syndrome in male breast cancer patients. Anticancer Res. 1997;17(6D):4293–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarquini A, Nicolosi A, Malloci A, Calò PG. Il carcinoma della mammella maschile. Chirurgia. 1996;9(4):330–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicolosi A, Malloci A, Calò PG. La ginecomastia. In: Rosato L, editor. La patologia chirurgica della mammella nell’adulto e nel bambino. Santhià (VC): GS Editrice; 2002. pp. 264–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fentiman IS, Fourquet A, Hortobagyi GN. Male breast cancer. Lancet. 2006;367(9510):595–604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korde LA, Zujewski JA, Kamin L, Giordano S, Domchek S, Anderson WF, Bartlett JM, Gelmon K, Nahleh Z, Bergh J, Cutuli B, Pruneri G, McCaskill-Stevens W, Gralow J, Hortobagyi G, Cardoso F. Multidisciplinary meeting on male breast cancer: summary and research recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(12):2114–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.5729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calò PG, Porcu G, Pollino V, Cabula C, Malloci A. Il tumore a cellule granulari della mammella maschile. Descrizione di un caso clinico. Minerva Chir. 1998;53:1043–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tuveri M, Calò PG, Mocci C, Nicolosi A. Florid papillomatosis of the male nipple. Am J Surg. 2010;200:e39–e40. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]