Abstract

Hepatic hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of the liver, often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. A 62-year-old woman was referred to our Institution under the suspicion of having an 8 cm-sized GIST. Due to the atypical features of the lesion on TC scan, a biopsy was performed. We report the case of pedunculated hepatic hemangioma with the aim to discuss the diagnostic approach, the possible causes of misdiagnosis and the opportunity of the laparoscopic approach.

Keywords: Hemangioma, Pedunculated, Liver

Introduction

Hepatic hemangiomas (HH) are the most common benign tumors of the liver, often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. It is a slow-growing, indolent neoplasia that can occur in all ages more frequently in females (1–3). Its prevalence ranges change from the 0,7–7% under in vivo diagnostic tools to 20% in autoptic series (3–5). Hormonal treatments, especially estrogenic, in stimulating and/or contraceptive use and replacement treatment for menopausal disorders, seems to be associated with an increasing in prevalence of HH (1, 6). The symptoms are non-specific, often digestive, more frequently associated with a complication (1). Its typical localization is intrahepatic, but hemangioma can present an extracapsular location, even pedunculated (7).

We report the case of pedunculated hepatic hemangioma with the aim to discuss the diagnostic approach, the possible causes of misdiagnosis and the opportunity of the laparoscopic approach.

Case report

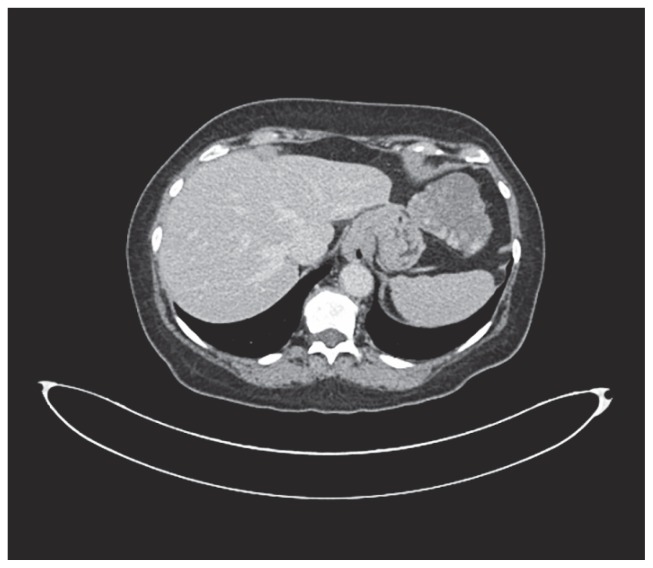

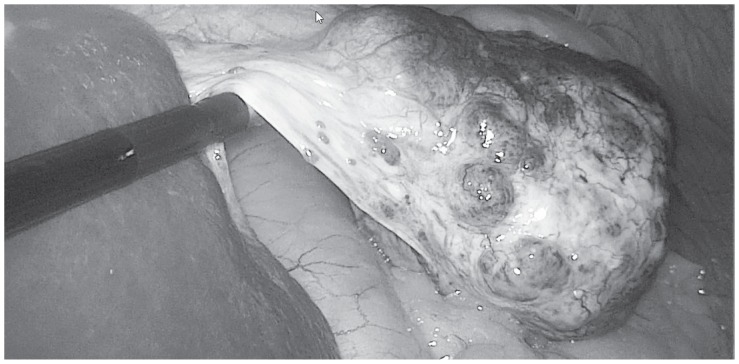

A 62-years-old woman was referred to our Institution under the suspicion of having an 8 cm-sized GIST. The CT scan showed a lesion originated from the greater curvature of the stomach with exophytic growth, irregular margin, hypodense on non-enhanced images, with heterogeneous enhancement more evident in delayed phases with predominant hypodense aspect (Fig. 1). This lesion was strictly adherent to diaphragm (no sure cleavage planes), to superior pole of spleen and left colic flexure. Some important hepatic findings were: presence of three globular enhanced lesion in arterial-phase with progressive centripetal enhancement, diagnosed like typical hemangiomas, and presence of other three lesions with peripheral enhancement and incomplete filling in delayed-phases images, diagnosed like atypical hemangiomas. Clinically patient presented a chronic dyspeptic condition. On physical examination, there were no abnormal findings. A laboratory workup on admission showed liver and renal function tests into the normal ranges. Tumor markers including alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigens 19-9 are also negatives. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed a 8 cm-sized mass in fundus and greater curvature of stomach, which was covered with normal gastric mucosa. Therefore, according to the oncologist counselling, a CT-guided shearing biopsy was performed. Pathology excluded a GIST and oriented to a benign me-senchymal neoplasia with a predominant angiomatous-like vascular component associated with miofibrobastic component. According to these findings and correlated with the presence of multiple hepatic lesion diagnosed like typical and atypical hemangiomas, we revised CT scan examination and we found a thin pedicle originating from the left liver lobe. MRI imaging showed multiple hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted images, hypointense on T1-weighted images, with peripheral globular enhancement in arterial phase and incomplete filling in dynamic phases of the study. The pedunculated lesion originating from the left liver lobe presented the same intensity features before and after gadolinium intake. So MRI imaging confirmed the diagnosis of multiple atypical hepatic hemangiomas, of which one pedunculated. The surgical excision of the mass was indicated for preventing ischemic complication related to volvulus along the pedicle or the rupture of the mass. Surgical removal of the mass was performed with a tri-port laparoscopic approach (Fig. 2) with a 10 mm. trocar in the navel, one more 10 mm. trocar in the left hypochondrium, along the mild-clavicular line and a third 5 mm. trocar in the right hypochondrium, perfectly symmetrical to the left one. An hemostatic collagen patch soacked in fibrinogen-thrombin, shaped for laparoscopic use, was applied upon the resection surface. Due to the easiness and the safety of the procedure, no drainage tube was applied. The patient was fed and mobilized in the evening of surgery day and discharged in the first postoperative day, after the passage of flatus had been observed. Pathological analysis provided a definitive diagnosis of pedunculated benign hepatic sclerosing hemangioma (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

CT findings: the tumor with polycyclic margins and diameter of about 8 cm shows on contrastographic examination typical enhancement poliglobular, detectable also in the late phase, compatible with hemangioma vascular pattern; on the contrary GIST presents homogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase, here undetectable. The apparent continuity relations with the gastric wall and the poor visibility of a thin peduncle induce error.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative findings.

Figure 3.

Specimen.

Discussion

HH are frequent focal lesions that consist in a congenital vascular malformation enlarging by ectasia in the shape of clusters of cavities bound by endothelial tissue, replete with blood and supported by collagenous walls. Some branches of hepatic artery feed these cavities. The etiopathogeny is unclear: the association between some steroid treatments have been showed and, on the other hand, an ereditary origin, although suspected, have never been supported with strong data (1, 8–9). Differently from hemangiomas involving other parenchymatous organs, the immunocompetence does not play a role (10). Most of HH are incidentally diagnosed during abdominal radiological imaging. The symptoms occur only in the presence of very large abdominal masses and/or complications. Abdominal palpable/visible mass, pain, hemorrhage, jaundice, nausea and vomiting may be complained (11, 12). The Kasabach-Merritt Syndrome (thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy in association with a large hemangioma) although rare, has been described (9). Ultrasounds (US), Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are useful for diagnosing HH. The US shows a typical hyperechoic pattern as a result of several interfaces (endothelium-collagen-blood) that reflects the ultrasounds. A “complex mass” aspect on US indicate necrotic areas (1). The Doppler US signal shows a minimal/absent intralesional or peripheral signal unlike the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) can improve the sensitivity of the US. The typical CEUS pattern is an intense peripheral contrast-enhancement in the arterial phase and a centripetal filling during the latest phases of the exam (1). A new contrast agent, the Perflubutane, has recently introduced in Japan, with the result of more detailed CEUS imaging compared to the conventional contrast agents currently in use in Europe. The Perflubutane CEUS seems to show real-time images more detailed compared to the CT or MRI images (13). The typical CT pattern is a hypodense, well bound lesion, showing peripheral enhancement during the arterial phase of the contrast injection and a progressive centripetal filling in the late phases. The CT presents strong limitations for lesion ≤ 5 mm. The MRI shows a well bound focal lesion hypointense on T1 and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The echo-time tend to increase on the contrary of the malignant lesions. The exam is more sensible and specific in detecting small lesions (< 2 cm.). The scintigraphic approach (99m-TC Red Blood Cells Scintigraphy) has a high sensitivity and an absolute specificity for identifying the lesion, but it is not useful for establishing its location (1). Due to the vascular structure of the lesion, the elective biopsy should be avoided (14). In our case report, it was misdiagnosed as gastric GIST caused by its irregular margin, a not clear cleavage planes from gastric wall, extrinsic compression of gastric fundus and body because of pedunculated feature and not detected pedicle originating from liver. Furthermore, the atypical radiologic finding caused some diagnostic confusion (a). In our case, on dynamic CT, heterogeneous enhancement due to the incomplete filling led to the misdiagnosis of GIST with necrotic, hemorrhagic and/or degenerative components. Misunderstood findings led us to perform this potentially dangerous procedure. MR imaging, performed on the basis of histological report, cleared up diagnosis. CT/MR imaging finding are closely correlated with the macroscopic appearance, which demonstrates changes such as haemorrhage, hyalinization and liquefation.

A major diameter > 4 cm is considered the cut-off between the small and the giant hemangiomas (16). A Chinese classification divided the HH into 3 groups: small (< 5 cm), large (major diameter between 5 and 10 cm) and giant (> 10 cm) (17). The size of the HH has been related to the symptoms in several studies, but the results are unconclusive. The growth pattern has been recently evaluated (18). Although the results of this study showed that the peak growth period was at the age 30 years and the peak growth size was 8–10 cm, it is generally accepted that the surgical indication does not depend on stated clinical/epidemiological factors such as age or size of the tumor. Only complications justify a surgical approach (16, 18), at least for typical intrahepatic lesions. The pedunculated variant of the HH is a very rare clinical entity in which the increasing risk of complications (rupture, volvulus) and, on the other hand, the easier surgical approach compared to the conventional hepatic resection makes the excision of the mass more attractive (7). The volvulus (torsion of the pedicle) usually leads to the infarction of the mass. In this case, clinically it presents as an acute abdominal pain that should be differentiated from different causes of acute abdomen, such as peritonitis or intestinal ischemia (19, 20). In the absence of these complications, pedunculated HH are most frequently asymptomatic. In a few cases a mass mimicking a submucosal tumor of the stomach has been reported (12, 21). Concerning the surgical technique, the laparoscopic approach remains indisputable, due to its minimally invasive characteristics, the easiness of the carrying out, the moderate postoperative pain, the possibility of a short-stay management, the low complications rate and the return of bowel activity (22–24). The optimal laparoscopic approach should give the benefits of the classical laparoscopic triangulation. In this perspective, the tri-port approach meets these criteria (25). The efficacy of the advanced hemostatic agents for implementing the hemostasis is strongly documented in different fields of surgery and it can be considered at least a good practice (26–28). In the present case we preferred a patch because of the ability of improving the hemostasis in a well defined area.

Conclusions

The pedunculated HH is a rare entity that should be suspected in the presence of a low-density mass revealed during an abdominal CT, sited in the left upper abdominal quadrant even if it seems originating from the stomach. In this case it should be useful an accurate exam of the imaging, aimed at the search of the pedicle and, in case of a coexisting intrahepatic angiomatous lesions, verifying the similar (intra- and extrahepatic) findings. The surgical removal of the mass is attractive owing to the ease execution in comparison with the risk of acute complications. The tri-port laparoscopic approach is safe and effective.

References

- 1.Bajenaru N, Balaban V, Savulescu F, Campeanu I, Patrascu T. Hepatic Hemangioma-review. J Med Life. 2015;8(Special Issue):4–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang W, Huang Z-Y, Ke C-S, et al. Surgical treatment of giant liver hemangioma larger than 10 cm: A single center’s experience with 86 patients. Medicine. 2015;94(34):1–8. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choy BY, Nguyen MH. The diagnosis and management of benign hepatic tumors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:401–12. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000159226.63037.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JM, Chung WJ, Jang BK, et al. Word J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(23):7326–30. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i23.7326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goidescu OC, Patrascu T. Ruptured liver cavernous hemangioma - rare cause of hemoperitoneum. J Med Life. 2015;8(1):73–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos Rodrigues AL, Silva Santana AC, Carvalho Araujo K, Crociati Meguins L, Felgueiras Rolo D, Pereira Ferreira M. Spontaneous rupture of a giant hepatic hemangioma: a rare source of hemoperitoneum. Case report. G Chir. 2010;31(3):83–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Ajjam M, Lacout A, Karji-Al Marzouqui M, Lacombe P, Marcy PY. Pedunculated hepatic hemangioma masquerading as a peritoneal tumor. A case report. Pol J Radiol. 2016;81:51–3. doi: 10.12659/PJR.895327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etamadi A, Golozar A, Ghassabian A, et al. Cavernous hemangioma of the liver: factors affecting disease progression in general hepatology practice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(4):354–8. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283451e7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moccheggiani F, Vincenzi P, Coletta M, et al. Prevalence and clinical outcome of hepatic haemangioma with specific reference to the risk of rupture: a large retrospective cross-sectional study. Digest and Liver Dis. 2016;48:309–14. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cappello M, Bravatà I, Cocorullo G, Cacciatore M, Florena AM. Splenic littoral cell hemangioendothelioma in patient with Crohn’s disease previously treated with immunomodulators and anti-TNF agents: a rare tumor linked to deep immunodepression. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(10):1863–5. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cochar R, Atiq M, Lee JH, et al. Giant hepatic hemangioma masquerading as a gastric subepithelial tumor. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY) 2013;9:396–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, Zhou Z. Hepatic Hemangioma masquerading as a tumor originating from the stomach. Oncology Letters. 2015;9:1406–8. doi: 10.3892/ol.2015.2863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruyama M, Isokawa O, Hoshiyama K, Hoshiyama A, Hoshiyama M, Hoshiyama Y. Diagnosis and management of giant hepatic hemangioma: the usefulness of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Intern J Hepatol. 2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/802180. Article ID 802180, 6 pages. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davies R. Haemorrhage after fine-needle aspiration biopsy of a hepatic hemangioma. Med J Aust. 1993;158(5):364. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1993.tb121823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SW, Kim HC, Yang DM, Won KY. Gastointestinal stromal tumors with thousand faces: atypical manifestations and causes of misdiagnosis on imaging. Clin Radiol. 2016;71(2):e130–42. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2015.10.025. Epub 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnelldorfer T, Ware A, Smoot R, Schleck CD, Harmsen W, Nagorney DM. Management of giant hemangioma of the liver: resection versus observation. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(6):724–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao W, Guo X, Dong J. Spontaneous rupture of hepatic hemangioma. A case report and literature review. Int J Exp Pathol. 2015;8(10):13426–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jing L, Liang H, Caifeng L, Jianjun Y, Feng X, Mengchao W, Yiqun Y. New recognition of the natural hystory and growth pattern of hepatic hemangioma in adults. Hepatol Res. 2016 doi: 10.1111/hepr.12610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agresta F, Ansaloni L, Baiocchi GL, et al. Laparoscopic approach to acute abdomen from the Consensus Development Conference of the Società Italiana di Chirurgia Endoscopica e nuove tecnologie (SICE), Associazione Chirurghi Ospedalieri Italiani (ACOI), Società Italiana di Chirurgia (SIC), Società Italiana di Chirurgia d’Urgenza e del Trauma (SICUT), Società Italiana di Chirurgia nell’Ospedalità Privata (SICOP), and the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) Surg Endosc. 2012;26(8):2134–64. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paladino NC, Inviati A, Di Paola V, Busuito G, Amodio E, Bonventre S, Scerrino G. Predictive factors of mortality in patients with acute mesenteric ischemia. A retrospective study. Ann Ital Chir. 2014;85(3):265–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moon HK, Kim HS, Heo GM, et al. A case of pedunculated hepatic hemangioma mimicking submucosal tumor of the stomach. Korean J Hepatol. 2011;17:66–70. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2011.17.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaillard M, Tranchart H, Lainas P, Tzanis D, Franco D, Dagher I. Ambulatory laparoscopic minor hepatic surgery: Retrospective observational study. J Visc Surg. 2015;152:292–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coelho FF, Pirola Kruger JA, Marques Fonseca G, et al. Laparoscopic liver resection: Experience based guidelines. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;8(1):5–26. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonventre S, Inviati A, Di Paola V, Morreale P, Di Giovanni S, Di Carlo P, Schifano D, Frazzetta G, Gulotta G, Scerrino G. Evaluating the efficacy of current treatments for reducing postoperative ileus: A randomized clinical trial in a single center. Minerva Chirurgica. 2014;69(1):47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agrusa A, Romano G, Cucinella G, Cocorullo G, Bonventre S, Salamone G, Di Buono G, De Vita G, Frazzetta G, Chianetta D, Sorce V, Bellanca G, Gulotta G. Laparoscopic, three-port and SILS cholecystectomy: a retrospective study. G Chir. 2013;34(9–10):249–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Docimo G, Tolone S, Conzo G, et al. A Gelatin-Thrombin Matrix Topical Hemostatic Agent (Floseal) in Combination With Harmonic Scalpel Is Effective in Patients Undergoing Total Thyroidectomy: A Prospective, Multicenter, Single-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Surgical Innovation. 2015;23(1):23–9. doi: 10.1177/1553350615596638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fingerhut A, Uranues S, Ettorre GM, et al. European Initial Hands-On Experience with HEMOPATCH, a Novel Sealing Hemostatic Patch: Application in General, Gastrointestinal, Biliopancreatic, Cardiac, and Urologic Surgery. Surg Technol Intern. 2014;25:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scerrino G, Paladino NC, Di Paola V, Morfino G, Amodio E, Gulotta G, Bonventre S. The use of haemostatic agents in thyroid surgery: efficacy and further advantages. Collagen-Fibrinogen-Thrombin Patch (CFTP) versus Cellulose Gauze. Ann Ital Chir. 2013;84(5):545–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]