Abstract

Reducing uric acid is hypothesized to lower blood pressure, although evidence is inconsistent. In this ancillary of the DASH-Sodium trial, we examined whether sodium-induced changes in serum uric acid (SUA) were associated with changes in blood pressure. One hundred and three adults with pre- or stage 1 hypertension, were randomly assigned to receive either the DASH diet or a control diet (typical of the average American diet) and were fed each of 3 sodium levels (low, medium, and high) for 30 days in random order. Body weight was kept constant. SUA was measured at baseline and following each feeding period. Participants were 55% women and 75% black. Mean age was 52 (SD, 10) years, and mean SUA at baseline was 5.0 (SD, 1.3) mg/dL. Increasing sodium intake from low to high reduced SUA (−0.4 mg/dL; P < 0.001), but increased systolic (4.3 mm Hg; P < 0.001) and diastolic blood pressure (2.3 mm Hg; P < 0.001). Furthermore, changes in SUA were independent of changes in systolic (P = 0.15) and diastolic (P = 0.63) blood pressure, regardless of baseline blood pressure, baseline SUA, and randomized diet, as well as sodium sensitivity. While both SUA and blood pressure were influenced by sodium, a common environmental factor, their effects were in opposite directions and were unrelated to each other. These findings do not support a consistent causal relationship between SUA and BP.

Elevated uric acid levels often accompany high blood pressure (1,2) and are associated with cardiovascular disease risk (3–7). Recently, several trials of urate-lowering therapy have shown that short-term reductions in uric acid are associated with a reduction in blood pressure (8–11). These studies have contributed to the hypothesis that hyperuricemia is a causal determinant of hypertension.

The DASH-Sodium trial was an isocaloric, controlled feeding study of the effects of the DASH diet and sodium intake on blood pressure (12). This study showed definitively that both the DASH diet and lower sodium consumption lowered blood pressure. However, in a recent ancillary study, we reported that while the DASH diet lowered uric acid, the lower sodium diet increased uric acid (13).

Thus the purpose of this study was to compare the within-person changes in uric acid with their changes in blood pressure following increased sodium intake. We hypothesized that short-term changes in uric acid would be independent of changes in blood pressure.

Methods

The original DASH-Sodium study was an investigator-initiated, multicenter, randomized trial sponsored by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute between September 1997 through November 1999 (12). This study randomized adults with prehypertension or stage 1 hypertension (not taking antihypertensive medications) and compared the effects of three levels of sodium intake on blood pressure in two distinct diets. The control diet reflected a typical American diet, while the intervention diet, the DASH diet, was rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy foods and reduced in saturated fat, total fat, and cholesterol (14). The DASH diet also emphasized whole grains, poultry, fish, and nuts, and de-emphasized red meat, sweets, and sugar-containing beverages than the typical American diet. In both diets, participants were fed each of three sodium levels: low (a target of 60 mmol per day), medium (a target of 120 mmol per day), and high (a target of 180 mmol per day). These targets were based on consumption of 2600 kcal of food per day, where the high sodium level (180 mmol/d) reflected typical sodium intake of a United States adult. The daily sodium intake was adjusted to reflect the total energy requirements of each participant, based on estimated need. As a result, larger or more active participants received more food and sodium compared to smaller and less active participants. Detailed descriptions of the diets are in Supplement Table S1.

Participants

The original study recruited adult men and women, aged 22 years and older, with an average systolic blood pressure (based on three screening visits) of 120 to 159 mm Hg and an average diastolic blood pressure of 80 to 95 mm Hg. We excluded persons with a prior diagnosis of heart disease, renal insufficiency, poorly controlled dyslipidemia, or diabetes mellitus. Furthermore, persons using antihypertensive agents, insulin, or drinking more than 14 alcoholic drinks a week were not eligible for this study (12).

The ancillary study presented here was limited to participants from the Johns Hopkins University clinical center in Baltimore, Maryland, based on uric acid measured at the time the study was performed. The Institutional Review Board at Johns Hopkins University approved the original study protocol. Written, informed consent was provided by all participants.

Controlled feeding

Participants were provided all of their food, including meals and snacks. All participants underwent an 11-14 day, run-in period during which they ate the high sodium, control diet. Subsequently, they were randomized to either the DASH or control diet according to a parallel-arm design. Within the context of either diet, participants ate each of three sodium levels for 30 days in random order. Sodium levels were separated by a 5-day break. Caloric intake was adjusted to maintain a constant weight throughout the trial.

Serum uric acid measurement

Fasting blood was collected from fasting participants at the Baltimore clinical center between 1997-1999. Specimens were centrifuged, aliquoted, and analyzed by Quest Diagnostics (Madison, New Jersey) for analysis without freezing or storage. Uric acid was measured via spectrophotometry.

Other covariate measurements and definitions

Baseline characteristics were gathered via questionnaires, laboratory specimens, and physical measurement. The primary outcome of the original DASH-sodium trial was blood pressure, measured in triplicate by protocol using random-zero, mercury sphygmomanometers after a 5 minute rest, while participants were seated, at three screening visits, twice during the run-in period, weekly during the first three weeks of each of the three 30-day intervention periods, and at five clinic visits during the last nine days (at least two during the final four days) of each intervention period. A high blood pressure at baseline was defined as having a mean, systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg of the three screening visits.

In addition to blood pressure, standard laboratory assays and techniques were used to measure serum total protein and albumin levels.

Statistical analysis

The study population was characterized with means (SD) and proportions. Mean uric acid and blood pressure measured at the end of each sodium period were compared to baseline measurements within each participant, using generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression models with a Huber and White robust variance estimator (15), which assumed an exchangeable working correlation matrix.

We also compared changes in uric acid with changes in systolic or diastolic blood pressure while going from a low to high sodium diet, using Pearson's coefficient and linear regression. These comparisons were performed in strata of baseline hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg), elevated baseline systolic blood pressure (≥ 140 mm Hg), elevated baseline diastolic blood pressure (≥ 90 mm Hg), salt sensitive participants (defined based on an absolute increase in mean arterial pressure ≥ 5 mm Hg or ≥ 5%), and baseline hyperuricemia (≥ 6 mg/dL). Interaction terms were used to compare effects across strata.

Finally, prior studies have reported that higher sodium intake can increase intravascular volume, artificially lowering biomarkers in blood specimens (16). To minimize this effect, we performed a sensitivity analysis, dividing the uric acid measures by either total protein or albumin (markers thought not be influenced by short-term changes in sodium) as a way to account for intravascular volume change, and compared within person change from baseline or from increasing sodium intake from low to high levels.

All analyses were performed with STATA version 14.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). Statistical significance was defined as P ≤ 0.05. Only 2 SUA values were missing from the control diet with medium sodium intake level, which were excluded from the analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of participants was 51.5 ± 9.7 years, 55% were women, 75% were black, 42% were obese, and 34% had hypertension (Table 1). The mean SUA level at baseline was 5.0 ±1.3 mg/dL. Mean alcohol consumption among study participants was low, just 1.3 g/d.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics overall and by diet

| Overall (N = 103) | Control Diet (N = 52) | DASH Diet (N = 51) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 51.5 (9.7) | 53.0 (9.7) | 49.9 (9.7) |

| Women, % | 55.3 | 48.1 | 62.7 |

| Black, % | 74.8 | 69.2 | 80.4 |

| High Blood Pressure*, % | 34.0 | 38.5 | 29.4 |

| Salt Sensitive (absolute)**, % | 32.0 | 40.4 | 23.5 |

| Salt Sensitive (percent)***, % | 35.9 | 46.2 | 25.5 |

| Blood pressure, mm Hg | |||

| Systolic | 135.6 (8.7) | 136.6 (8.8) | 134.6 (8.7) |

| Diastolic | 85.6 (3.8) | 85.6 (3.7) | 85.6 (4.0) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.5 (4.4) | 30.0 (4.8) | 29.1 (3.9) |

| Body mass index ≥30, % | 41.7 | 46.2 | 37.3 |

| eGFRcys, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 93.7 (21.0) | 93.9 (19.2) | 93.4 (22.8) |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 99.8 (18.5) | 99.1 (20.3) | 100.6 (16.6) |

| Fasting triglycerides, mg/dL | 122.1 (151.7) | 116.5 (65.4) | 127.8 (206.2) |

| Total protein, g/dL | 7.2 (0.4) | 7.2 (0.4) | 7.3 (0.4) |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.1 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.2) |

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 4.96 (1.29) | 5.02 (1.30) | 4.90 (1.29) |

| Alcohol intake, g/d | 1.3 (2.5) | 1.5 (2.6) | 1.2 (2.3) |

Defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mm Hg.

Defined as an increase in MAP of >5 mm Hg when going from the low to high sodium intake levels

Defined as an increase in MAP of >5% during high versus low salt intake

Change from Baseline

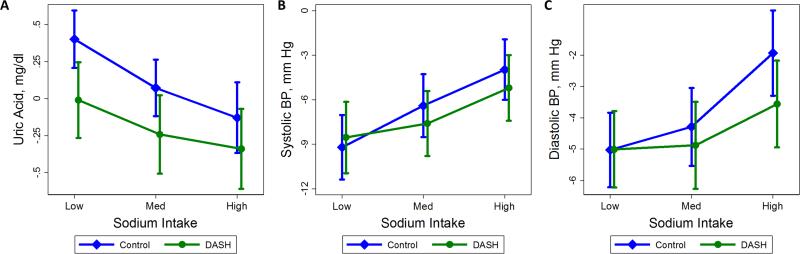

We determined mean uric acid levels, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure at baseline and after each of the three feeding sodium periods for both the control and DASH diets (Table 2). We further determined change in uric acid levels, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure from baseline at the end of each sodium level period by diet (Figure 1 & Supplement Table S2). Adopting the low sodium, control diet significantly increased uric acid level (0.4 mg/dL; P < 0.001); while the medium or high sodium and DASH diets, lowered uric acid levels, −0.2 mg/dL (P = 0.07) and −0.3 mg/dL (P = 0.01) respectively. Both diets lowered systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure from baseline at all sodium levels.

Table 2.

Mean uric acid, systolic blood pressure, and diastolic blood pressure at baseline and by sodium intake

| Baseline | Low Sodium | Medium Sodium | High Sodium | High versus Low Sodium |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Difference (95% CI) | P | |

| Control Diet | ||||||

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 5.0 (1.3) | 5.4 (1.3) | 5.1 (1.3) | 4.9 (1.4) | −0.5 (−0.7,−0.3) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 136.6 (8.8) | 127.4 (10.7) | 130.2 (11.5) | 132.6 (11.3) | 5.2 (3.0, 7.5) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 85.6 (3.7) | 80.6 (5.2) | 81.3 (5.4) | 83.7 (6.2) | 3.1 (1.7, 4.5) | <0.001 |

| Dash Diet | ||||||

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 4.9 (1.3) | 4.9 (1.1) | 4.6 (1.1) | 4.6 (1.1) | −0.3 (−0.5,−0.1) | 0.003 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 134.6 (8.7) | 126.0 (9.9) | 127.0 (10.5) | 129.4 (10.8) | 3.3 (1.5, 5.2) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 85.6 (4.0) | 80.6 (5.4) | 80.6 (6.7) | 82.0 (6.8) | 1.4 (0.2, 2.6) | 0.018 |

| Overall | ||||||

| Uric acid, mg/dL | 5.0 (1.3) | 5.2 (1.2) | 4.9 (1.2) | 4.7 ( 1.3) | −0.4 (−0.6,−0.3) | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 135.6 (8.7) | 126.7 (10.3) | 128.6 (11.1) | 131.0 (11.1) | 4.3 (2.8, 5.8) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 85.6 (3.8) | 80.6 (5.3) | 81.0 (6.1) | 82.8 (6.6) | 2.3 (1.4, 3.2) | <0.001 |

Figure 1.

Within person, baseline changes in (A) uric acid, (B) systolic blood pressure, and (C) diastolic blood pressure levels after the low sodium feeding period, the medium sodium feeding period, and the end of the high sodium feeding period for either the control (diamonds, blue) or DASH (circles, green) diets. Vertical lines represent 95% confidence intervals.

High versus Low Sodium Intake

Overall, increasing sodium intake (from low to high) lowered serum uric acid (−0.4 mg/dL; P < 0.001), but increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure, 4.3 mm Hg and 2.3 mm Hg, respectively (both P-values < 0.001) (Table 2). Similar reductions in uric acid with concurrent increases in systolic and diastolic blood pressure were observed when stratified by DASH and control diets as well. Standardizing uric acid measures with total protein or albumin did not meaningfully change our findings (Supplement Table S3).

Comparison with changes in blood pressure

The effects on uric acid of increasing sodium intake (from low to high levels) were compared with effects on systolic and diastolic blood pressure via linear regression (Figure 2). Ultimately they were unrelated (systolic blood pressure: P = 0.15; diastolic blood pressure: P = 0.63). This lack of association was observed regardless of baseline blood pressure, blood pressure response to sodium, or baseline uric acid level (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of change in systolic or diastolic blood pressure (y-axes) versus change in uric acid (x-axis). Dashed line represents linear regression. P-value corresponds to the slope of the line.

Table 3.

Association between overall within-person change in uric acid with change in systolic or diastolic blood pressure when increasing sodium intake from low to high

| N | Change in SBP |

Change in DBP |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | β | P | P-interaction | r | β | P | P-interaction | ||

| Overall | 103 | −0.14 | −1.4 | 0.15 | − | −0.05 | −0.3 | 0.63 | |

| Baseline hypertension | |||||||||

| No | 68 | −0.22 | −1.9 | 0.07 | 0.19 | −0.04 | −0.2 | 0.72 | 0.57 |

| Yes | 35 | 0.09 | 1.2 | 0.61 | 0.07 | 0.6 | 0.67 | ||

| Elevated SBP | |||||||||

| No | 74 | −0.22 | −1.9 | 0.06 | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.4 | 0.56 | 0.21 |

| Yes | 29 | 0.18 | 2.5 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 1.6 | 0.32 | ||

| Elevated DBP | |||||||||

| No | 87 | −0.13 | −1.2 | 0.24 | 0.60 | −0.03 | −0.2 | 0.79 | 0.64 |

| Yes | 16 | −0.21 | −3.2 | 0.43 | −0.13 | −1.3 | 0.63 | ||

| Salt Sensitive (absolute)* | |||||||||

| No | 70 | −0.13 | −0.9 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.4 | 0.44 | 0.78 |

| Yes | 33 | 0.07 | 0.4 | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.79 | ||

| Salt Sensitive (percent)* | |||||||||

| No | 66 | −0.11 | −0.7 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.5 | 0.39 | 0.78 |

| Yes | 37 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.84 | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.75 | ||

| Hyperuricemia > 6 | |||||||||

| No | 79 | −0.14 | −1.4 | 0.23 | 0.99 | −0.06 | −0.40 | 0.62 | 0.87 |

| Yes | 24 | −0.16 | −1.4 | 0.46 | −0.03 | −0.1 | 0.90 | ||

Based an increase in MAP of >5 mm Hg during high versus low salt intake

**Based an increase in MAP of >5% during high versus low salt intake

Discussion

In this ancillary study of the DASH-sodium trial, we report that sodium intake significantly affects uric acid and blood pressure in opposite directions. Increasing sodium intake decreased uric acid while increasing systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Furthermore, these changes were independent of baseline blood pressure or uric acid values. These findings suggest that uric acid is not a meaningful causal determinant of blood pressure in the context of changes in dietary sodium intake.

While the relationship between sodium intake and hypertension is well-established, its relationship with uric acid is controversial. It has been hypothesized that higher uric acid levels represent an evolutionary advantage in homo sapiens species, allowing them to maintain blood pressure when access to sodium was scarce (17). This theory was demonstrated in uricase-deficient rat models showing an increase in blood pressure from hyperuricemia in the context of a low sodium diet (18). Additional rat models have supported this hypothesis, showing that uric acid causes upregulation and activation of epithelial sodium channels in the nephron (19). This was also observed in an ecological study of acculturation of the Solomon Islands conducted in the 1970s. Uric acid levels were higher among island populations consuming a low salt diet (20). Subsequent observational studies, did not support this hypothesis, however, showing that higher sodium intake was associated with higher uric acid levels cross-sectionally (21,22) as well as with an increased risk of hyperuricemia in the future (23). There is a paucity of clinical trials examining this relationship. One trial performed in 27 men showed that reducing sodium from 200 meq/d to 20 meq/d increased uric acid levels by 1 mg/dL (P < 0.001) (24). Further, a crossover trial of 147 non-obese, normotensive adults found that 7 days of high versus low sodium intake (300 versus 20 mmol/d), significantly decreased SUA approximately by 1 mg/dL (25).

We can speculate as to the mechanism by which higher sodium intake decreases uric acid. While increased sodium intake has been noted to cause increased intravascular volume (16), which could cause a hemodilutional effect of sodium on uric acid, adjusting for volume status did not negate the results of our study. It is also possible that the relationship between sodium intake and uric acid reduction results from effects of sodium intake on glomerular filtration rate and excretion or absorption of urate. Previous physiology studies have shown that reabsorption of sodium and urate accompany one another (26,27) at different sites in the nephron (28–30). Thus, it is possible that decreased renal reabsorption of sodium from excess sodium intake, contributes to a decrease in urate reabsorption. Finally, this relationship may reflect action of the renin-angiotensin system, as uric acid is inversely related to vascular resistance (31) and renal blood flow (32).

Our study showed that at least in the short-term, uric acid and blood pressure not only changed significantly in opposite directions, but these changes were not related to each other. This was observed in at least one other study of 21 healthy subjects, in which change in mean arterial pressure was not associated with uric acid levels (33). Our findings contribute to the ongoing debate regarding the role of uric acid in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Several animal studies have demonstrated that hyperuricemia precedes hypertension (18) and contributes to histologic changes known to elevate blood pressure (34). This association has further been demonstrated in a large number of observational studies (3–6,35–38). Moreover, there is emerging evidence that reducing uric acid with pharmacologic agents like allopurinol, reduces blood pressure (8–11). However, this relationship has not been observed in all trials of urate-lowering therapy (39–41). Meanwhile, Mendelian randomization studies of genes known to influence uric acid levels have shown that while a genetic predisposition toward hyperuricemia is associated with high risk of gout, it is not associated with higher risk of hypertension (42). However, even these findings are inconsistent with some gene studies showing an association (43,44) and others showing no association (45–47).

Our study has unclear implications on risk for cardiovascular outcomes. While higher blood pressure has been unequivocally associated with increased risk for cardiovascular disease (48,49), the role of uric acid has remained unclear, with some studies showing strong associations (35,36,50) and other showing no association with cardiovascular disease (51). In this regard, the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP) trial was informative, showing that small increases in uric acid from thiazides did not influence the benefit achieved by better blood pressure control; whereas large increases in uric acid did attenuate the risk reduction from blood pressure reduction (52). It is possible that these small, acute changes have little impact on the subsequent development of cardiovascular disease. However, the utility of uric acid as a marker of cardiovascular disease risk should not be discounted on the basis of our study, given the relatively short duration of the intervention.

Our study has limitations. First, this study was not conducted in persons with prior cardiovascular disease, advanced kidney disease, or medication-treated diabetes, all conditions associated with both hyperuricemia and hypertension. Further, we did not measure urinary excretion of uric acid, which could provide additional clarity as to whether higher excretion was responsible for reducing uric acid. Third, while our findings do not suggest a causal relationship between uric acid levels and blood pressure, it should be noted that such a relationship could still exist, but perhaps is overwhelmed or negated by the opposing effects of dietary sodium on uric acid or blood pressure. It is also important to note that participants of the DASH-Sodium trial were less obese and had a lower proportion of participants with hypertension (34%) than some of the initial studies showing relationships between uric acid and blood pressure. Thus, our findings should be interpreted as non-casual in the context of dietary changes in sodium among a population similar to participants in the DASH-Sodium trial. Fourth, our sample size is potentially underpowered to see a significant relationship between uric acid and blood pressure. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the direction of the association is inverse, even though non-significant. Finally, the parallel design of the dietary intervention precluded examination of within person changes in uric acid and blood pressure across diets (DASH versus control).

This study also has important strengths. Each person consumed the three sodium diets in random order. Thus, they served as their own control, allowing us to determine the effects of sodium on uric acid and blood pressure within each participant. Further, weight did not change during the trial and the study population was diverse. Finally, diets were highly regulated with excellent compliance from study participants throughout the trial.

In conclusion, our findings show that higher sodium intake decreases uric acid, but increases blood pressure. These effects are not only in opposing directions, but independent of each other. Ultimately, these findings are not consistent with a causal relationship between SUA and blood pressure, and do not support use of urate-lowering therapies as an intervention to lower blood pressure.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Higher dietary sodium intake increases blood pressure yet decreases serum uric acid

Changes in blood pressure associated with increased sodium intake are independent of changes in uric acid

These findings do not support a causal relationship between serum uric acid and blood pressure

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the study participants for their sustained commitment to the DASH–Sodium Trial; to the Almond Board of California, Beatrice Foods, Bestfoods, Cabot Creamery, C.B. Foods, Dannon, Diamond Crystal Specialty Foods, Elwood International, Hershey Foods, Hormel Foods, Kellogg, Lipton, McCormick, Nabisco U.S. Foods Group, Procter & Gamble, Quaker Oats, and Sun-Maid Growers for donating food; to Frost Cold Storage for food storage.

Supported by cooperative agreements and grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (U01-HL57173, to Brigham and Women's Hospital; U01-HL57114, to Duke University; U01-HL57190, to Pennington Biomedical Research Institute; U01-HL57139 and K08 HL03857-01, to Johns Hopkins University; and U01-HL57156, to Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research) and by the General Clinical Research Center Program of the National Center for Research Resources (M01-RR02635, to Brigham and Women's Hospital, and M01-RR00722, to Johns Hopkins University).

SPJ is supported by a NIH/NIDDK T32DK007732-20 Renal Disease Epidemiology Training Grant.

Abbreviations used

- DASH

Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension

- GEE

generalized estimating equation

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov, number: NCT00000608

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Juraschek SP, Kovell LC, Miller ER, Gelber AC. Dose-response association of uncontrolled blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk factors with hyperuricemia and gout. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e56546. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Comorbidities of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: NHANES 2007-2008. Am J Med. 2012 Jul;125(7):679–687.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ndrepepa G, Braun S, King L, Fusaro M, Tada T, Cassese S, et al. Uric acid and prognosis in angiography-proven coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2013 Mar;43(3):256–66. doi: 10.1111/eci.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ioannou GN, Boyko EJ. Effects of menopause and hormone replacement therapy on the associations of hyperuricemia with mortality. Atherosclerosis. 2013 Jan;226(1):220–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakoda M, Masunari N, Yamada M, Fujiwara S, Suzuki G, Kodama K, et al. Serum uric acid concentration as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality: a longterm cohort study of atomic bomb survivors. J Rheumatol. 2005 May;32(5):906–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niskanen LK, Laaksonen DE, Nyyssönen K, Alfthan G, Lakka H-M, Lakka TA, et al. Uric acid level as a risk factor for cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in middle-aged men: a prospective cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Jul 26;164(14):1546–51. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.14.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juraschek SP, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Woodward M. Serum uric acid and the risk of mortality during 23 years follow-up in the Scottish Heart Health Extended Cohort Study. Atherosclerosis. 2014 Apr;233(2):623–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siu Y-P, Leung K-T, Tong MK-H, Kwan T-H. Use of allopurinol in slowing the progression of renal disease through its ability to lower serum uric acid level. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006 Jan;47(1):51–9. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez-Pozo SE, Schold J, Nakagawa T, Sánchez-Lozada LG, Johnson RJ, Lillo JL. Excessive fructose intake induces the features of metabolic syndrome in healthy adult men: role of uric acid in the hypertensive response. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010 Mar;34(3):454–61. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feig DI, Soletsky B, Johnson RJ. Effect of allopurinol on blood pressure of adolescents with newly diagnosed essential hypertension: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008 Aug 27;300(8):924–32. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soletsky B, Feig DI. Uric acid reduction rectifies prehypertension in obese adolescents. Hypertension. 2012 Nov;60(5):1148–56. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.196980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacks FM, Svetkey LP, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Bray GA, Harsha D, et al. Effects on blood pressure of reduced dietary sodium and the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2001 Jan 4;344(1):3–10. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Juraschek SP, Gelber AC, Choi HK, Appel LJ, Miller ER., III Effects of the Dietary Approaches To Stop Hypertension (DASH) Diet and Sodium Intake on Serum Uric Acid. Arthritis Rheum. 2016 doi: 10.1002/art.39813. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1997 Apr 17;336(16):1117–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704173361601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48(4):817–38. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson DE, Parsons BA, McNeely JC, Miller ER. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure is accompanied by slow respiratory rate: results of a clinical feeding study. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2007 Jul;1(4):256–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watanabe S, Kang D-H, Feng L, Nakagawa T, Kanellis J, Lan H, et al. Uric acid, hominoid evolution, and the pathogenesis of salt-sensitivity. Hypertension. 2002 Sep;40(3):355–60. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000028589.66335.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzali M, Hughes J, Kim YG, Jefferson JA, Kang DH, Gordon KL, et al. Elevated uric acid increases blood pressure in the rat by a novel crystal-independent mechanism. Hypertension. 2001 Nov;38(5):1101–6. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.092839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu W, Huang Y, Li L, Sun Z, Shen Y, Xing J, et al. Hyperuricemia induces hypertension through activation of renal epithelial sodium channel (ENaC). Metab Clin Exp. 2016 Mar;65(3):73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page LB, Damon A, Moellering RC. Antecedents of cardiovascular disease in six Solomon Islands societies. Circulation. 1974 Jun;49(6):1132–46. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.49.6.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nerbass FB, Pecoits-Filho R, McIntyre NJ, McIntyre CW, Taal MW. High sodium intake is associated with important risk factors in a large cohort of chronic kidney disease patients. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015 Jul;69(7):786–90. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hou L, Zhang M, Han W, Tang Y, Xue F, Liang S, et al. Influence of Salt Intake on Association of Blood Uric Acid with Hypertension and Related Cardiovascular Risk. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4):e0150451. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forman JP, Scheven L, de Jong PE, Bakker SJL, Curhan GC, Gansevoort RT. Association between sodium intake and change in uric acid, urine albumin excretion, and the risk of developing hypertension. Circulation. 2012 Jun 26;125(25):3108–16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.096115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Egan BM, Weder AB, Petrin J, Hoffman RG. Neurohumoral and metabolic effects of short-term dietary NaCl restriction in men. Relationship to salt-sensitivity status. Am J Hypertens. 1991 May;4(5 Pt 1):416–21. doi: 10.1093/ajh/4.5.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruppert M, Diehl J, Kolloch R, Overlack A, Kraft K, Göbel B, et al. Short-term dietary sodium restriction increases serum lipids and insulin in salt-sensitive and salt-resistant normotensive adults. Klin Wochenschr. 1991;69(Suppl 25):51–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ter Maaten JC, Voorburg A, Heine RJ, Ter Wee PM, Donker AJ, Gans RO. Renal handling of urate and sodium during acute physiological hyperinsulinaemia in healthy subjects. Clin Sci. 1997 Jan;92(1):51–8. doi: 10.1042/cs0920051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quiñones Galvan A, Natali A, Baldi S, Frascerra S, Sanna G, Ciociaro D, et al. Effect of insulin on uric acid excretion in humans. Am J Physiol. 1995 Jan;268(1 Pt 1):E1–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1995.268.1.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinman EJ, Knight TF, McKenzie R, Eknoyan G. Dissociation of urate from sodium transport in the rat proximal tubule.=. Kidney Int. 1976 Oct;10(4):295–300. doi: 10.1038/ki.1976.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weinman EJ, Steplock D, Suki WN, Eknoyan G. Urate reabsorption in proximal convoluted tubule of the rat kidney. Am J Physiol. 1976 Aug;231(2):509–15. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.2.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roch-Ramel F, Diezi-Chomety F, De Rougemont D, Tellier M, Widmer J, Peters G. Renal excretion of uric acid in the rat: a micropuncture and microperfusion study. Am J Physiol. 1976 Mar;230(3):768–76. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.3.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Omvik P, Lund-Johansen P. Is sodium restriction effective treatment of borderline and mild essential hypertension? A long-term haemodynamic study at rest and during exercise. J Hypertens. 1986 Oct;4(5):535–41. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198610000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Messerli FH, Frohlich ED, Dreslinski GR, Suarez DH, Aristimuno GG. Serum uric acid in essential hypertension: an indicator of renal vascular involvement. Ann Intern Med. 1980 Dec;93(6):817–21. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-6-817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ter Maaten JC, Voordouw JJ, Bakker SJ, Donker AJ, Gans RO. Salt sensitivity correlates positively with insulin sensitivity in healthy volunteers. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999 Mar;29(3):189–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1999.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazzali M, Kanellis J, Han L, Feng L, Xia Y-Y, Chen Q, et al. Hyperuricemia induces a primary renal arteriolopathy in rats by a blood pressure-independent mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2002 Jun;282(6):F991–997. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00283.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang J, Alderman MH. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular mortality the NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971-1992. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2000 May 10;283(18):2404–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.18.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Gunter EW, Byers T. Relation of serum uric acid to mortality and ischemic heart disease. The NHANES I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Apr 1;141(7):637–44. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reunanen A, Takkunen H, Knekt P, Aromaa A. Hyperuricemia as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1982;668:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1982.tb08521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feig DI, Kang D-H, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2008 Oct 23;359(17):1811–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0800885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rekhraj S, Gandy SJ, Szwejkowski BR, Nadir MA, Noman A, Houston JG, et al. High-dose allopurinol reduces left ventricular mass in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Mar 5;61(9):926–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Driscoll JG, Green DJ, Rankin JM, Taylor RR. Nitric oxide-dependent endothelial function is unaffected by allopurinol in hypercholesterolaemic subjects. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1999 Oct;26(10):779–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Segal MS, Srinivas TR, Mohandas R, Shuster JJ, Wen X, Whidden E, et al. The effect of the addition of allopurinol on blood pressure control in African Americans treated with a thiazide-like diuretic. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015 Aug;9(8):610–619.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Q, Köttgen A, Dehghan A, Smith AV, Glazer NL, Chen M-H, et al. Multiple genetic loci influence serum urate levels and their relationship with gout and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010 Dec;3(6):523–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.934455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mallamaci F, Testa A, Leonardis D, Tripepi R, Pisano A, Spoto B, et al. A polymorphism in the major gene regulating serum uric acid associates with clinic SBP and the white-coat effect in a family-based study. J Hypertens. 2014 Aug;32(8):1621–1628. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000224. discussion 1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parsa A, Brown E, Weir MR, Fink JC, Shuldiner AR, Mitchell BD, et al. Genotype-based changes in serum uric acid affect blood pressure. Kidney Int. 2012 Mar;81(5):502–7. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hughes K, Flynn T, de Zoysa J, Dalbeth N, Merriman TR. Mendelian randomization analysis associates increased serum urate, due to genetic variation in uric acid transporters, with improved renal function. Kidney Int. 2014 Feb;85(2):344–51. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sluijs I, Holmes MV, van der Schouw YT, Beulens JWJ, Asselbergs FW, Huerta JM, et al. A Mendelian Randomization Study of Circulating Uric Acid and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2015 Aug;64(8):3028–36. doi: 10.2337/db14-0742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voruganti VS, Nath SD, Cole SA, Thameem F, Jowett JB, Bauer R, et al. Genetics of Variation in Serum Uric Acid and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Mexican Americans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Feb;94(2):632–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.He J, Ogden LG, Vupputuri S, Bazzano LA, Loria C, Whelton PK. Dietary sodium intake and subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease in overweight adults. JAMA. 1999 Dec 1;282(21):2027–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.21.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tuomilehto J, Jousilahti P, Rastenyte D, Moltchanov V, Tanskanen A, Pietinen P, et al. Urinary sodium excretion and cardiovascular mortality in Finland: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001 Mar 17;357(9259):848–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Høieggen A, Alderman MH, Kjeldsen SE, Julius S, Devereux RB, De Faire U, et al. The impact of serum uric acid on cardiovascular outcomes in the LIFE study. Kidney Int. 2004 Mar;65(3):1041–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Culleton BF, Larson MG, Kannel WB, Levy D. Serum uric acid and risk for cardiovascular disease and death: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med. 1999 Jul 6;131(1):7–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-1-199907060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Franse LV, Pahor M, Di Bari M, Shorr RI, Wan JY, Somes GW, et al. Serum uric acid, diuretic treatment and risk of cardiovascular events in the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). J Hypertens. 2000 Aug;18(8):1149–54. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018080-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harsha DW, Sacks FM, Obarzanek E, Svetkey LP, Lin P-H, Bray GA, et al. Effect of dietary sodium intake on blood lipids: results from the DASH-sodium trial. Hypertension. 2004 Feb;43(2):393–8. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000113046.83819.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Svetkey LP, Sacks FM, Obarzanek E, Vollmer WM, Appel LJ, Lin PH, et al. The DASH Diet, Sodium Intake and Blood Pressure Trial (DASH-sodium): rationale and design. DASH-Sodium Collaborative Research Group. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999 Aug;99(8 Suppl):S96–104. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(99)00423-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.