Abstract

Purpose

Residual symptoms of depressive disorder are major predictors of relapse of depression and lower quality of life. This study aims to investigate the prevalence of residual symptoms, relapse rates, and quality of life among patients with depressive disorder.

Patients and methods

Data were collected during the Thai Study of Affective Disorder (THAISAD) project. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) was used to measure the severity and residual symptoms of depression, and EQ-5D instrument was used to measure the quality of life. Demographic and clinical data at the baseline were described by mean ± standard deviation (SD). Prevalence of residual symptoms of depression was determined and presented as percentage. Regression analysis was utilized to predict relapse and patients’ quality of life at 6 months postbaseline.

Results

A total of 224 depressive disorder patients were recruited. Most of the patients (93.3%) had at least one residual symptom, and the most common was anxiety symptoms (76.3%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71–0.82). After 3 months postbaseline, 114 patients (50.9%) were in remission and within 6 months, 44 of them (38.6%) relapsed. Regression analysis showed that residual insomnia symptoms were significantly associated with these relapse cases (odds ratio [OR] =5.290, 95% CI, 1.42–19.76). Regarding quality of life, residual core mood and insomnia significantly predicted the EQ-5D scores at 6 months postbaseline (B =−2.670, 95% CI, −0.181 to −0.027 and B =−3.109, 95% CI, −0.172 to −0.038, respectively).

Conclusion

Residual symptoms are common in patients receiving treatment for depressive disorder and were found to be associated with relapses and quality of life. Clinicians need to be aware of these residual symptoms when carrying out follow-up treatment in patients with depressive disorder, so that prompt action can be taken to mitigate the risk of relapse.

Keywords: Thai, residual symptoms, depression, relapse, quality of life, treatment

Introduction

Residual symptoms among those suffering from major depressive disorder (MDD) are those that remain during treatment.1 Such symptoms have been reported among groups of patients, responders (usually defined as those who experience a 50% or greater improvement when using symptom measures such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAMD]), and remitters (typically defined as those with an HAMD score of ≤7). Residual symptoms include both symptoms that persist at baseline and new-onset symptoms.2,3

By understanding the nature of residual symptoms, clinicians might be able to identify and treat specific symptoms to optimize clinical and functional outcomes. Also, clinicians need to be aware of those symptoms that are usually underrecognized as symptoms of depression and need to be ruled out for causes from medical condition, such as fatigue, lack of energy, and a diminished ability to think and concentrate or decide effectively.1 Moreover, a good understanding of such residual symptoms will help clinicians differentiate between symptoms present at baseline and persist throughout treatment from those that emerge during treatment. In the study of McClintock et al,4 the most common residual symptoms found to persist during treatment were mid-nocturnal insomnia, sad mood, and a decreased level of concentration or decision-making ability, while the most common symptoms to emerge during treatment were mid-nocturnal insomnia and decreased general interest.

The presence of residual symptoms can have many implications. First of all, the presence of such symptoms is a major predictor of relapse among MDD patients who have and have not experienced full remission. A number of studies have shown that people with residual symptoms face a greater risk of relapse than fully recovered asymptomatic patients.1,3,5 In terms of functioning, residual symptoms are also associated with persistent functional impairment. A study by Romera et al2 found that the level of association between residual symptom domains and patient functioning varied according to the symptom types, with a marked association found for residual core mood symptoms. Also, the factors that associated with normal functioning were an absence of core mood symptoms, an absence of insomnia symptoms, a shorter episode length, and an improved baseline functioning.

Residual symptoms can lead to a lower quality of life among depressive patients,1,6 though not many research studies have reported on this relationship, especially when using EQ-5D – a standardized preference-based measure of health status that can be compared across disorders and cultures. Woo et al7 found that nonremitted MDD patients – especially those with more severe somatic symptoms – showed a significantly lower EQ-5D index scores than those with only mild to moderate somatic symptoms.

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of residual symptoms among a group of patients being treated for depressive disorders and the effects of these symptoms on their relapse rates and quality of life.

Patients and methods

This study is based on data collected during the Thai Study of Affective Disorder (THAISAD) research project, which is a prospective, 12-month follow-up study. The participants were diagnosed as having MDD and/or dysthymic disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR), using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Inventory (MINI) and were also assessed for depression by trained clinicians and psychiatric investigators and were receiving treatment at 11 hospitals across Thailand. Ethical approval for this study was provided by both the Joint Research Ethics Committee of Thailand and the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Public Health in Thailand. All the participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Only participants who were able to give their consent by themselves were recruited. Among them, participants whose age was 60 years and older or had major neurocognitive disorders were excluded. The rationale, design, and methods used, as well as the participants’ characteristics for the THAISAD project, have already been documented elsewhere.8

Measures and definitions

HAMD

The HAMD instrument is used widely to measure the severity of depression among patients and the residual symptoms experienced during treatment. The Thai version of HAMD has been found to have good internal consistency (alpha coefficients =0.74), and its concurrent validity – as compared to the Global Assessment Scale – has also been found to be satisfactory (Spearman’s correlation coefficient =−0.82).9 The HAMD instrument is also used to assess treatment responses. Using the instrument, remission is defined as an HAMD-17 score of ≤7 and a response as an improvement of 50% or more over the baseline score.

EQ-5D

EQ-5D is a generic measure of health status that provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value that can be used in the clinical and economic evaluation of health care and also in population health surveys. Currently, EQ-5D is being used in a number of different countries by clinical researchers working across a variety of clinical areas and has now been translated into many languages.10 The measure is based on a descriptive system that defines health across five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities (eg, during work or study, in the household, and during family or leisure activities), pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has three response categories: no problems, some problems, and severe problems. Also, it is complemented by a visual analogue scale (VAS), for which 0 represents the worst imaginable level of health and 100 represents the best imaginable level of health.11 During the research for this study, the EQ-5D instrument was used to measure quality of life.

Methods

We used the definition of residual symptoms described by Dombrovski et al,12 with the presence of residual core mood symptoms indicated by a score of 1 or more on the HAMD-17 core symptom subscale (depressed mood [Item 1], guilt [Item 2], suicide [Item 3], and anergia/anhedonia [Item 7]). The presence of residual insomnia symptoms was indicated by a score of 1 or more on the HAMD-17 sleep subscale (early [Item 4], middle [Item 5], and late insomnia [Item 6]). The presence of residual anxiety symptoms was indicated by a score of 1 or more on the HAMD-17 anxiety subscale (agitation [Item 9], psychic anxiety [Item 10], somatic anxiety [Item 11], and hypochondriasis [Item 15]). Finally, residual somatic symptoms were indicated by a score of 1 or more for Item 13 of the HAMD-17.

Data analysis

Demographic and clinical data at the baseline were described by the mean ± SD. The prevalences of residual symptoms in both the remitted and nonremitted groups were presented as a percentage. Regression analysis was used to predict relapse at 6-month postbaseline and also the impact of treatment on the patients’ quality of life.

Results

Table 1 presents the basic characteristics and clinical data for the participants in this study. The dosage of main antidepressants used in this study is shown in Table 2. There are eight patients who received additional formal psychotherapy (four patients receive psychodynamic psychotherapy and four patients receive cognitive behavior therapy) other than supportive counseling or supportive psychotherapy during medical treatment. The mean HAMD score was 20.72 (SD =7.24), which signifies the presence of moderate depression.13 After 3-month follow-up, the HAMD score had decreased to 10.08 (SD =8.51), which indicates the presence of mild depression. The EQ-5D quality of life score was also found to increase at 3-month follow-up.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical data of the participants

| Sociodemographic data | |

| Number of participants (N) | 224 |

| Age, mean (SD) | 47.2 (15.2) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 51 (22.8) |

| Female | 173 (77.2) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Less than elementary | 27 (12.1) |

| Elementary to junior | 70 (31.3) |

| High school | 57 (25.4) |

| Bachelor or higher | 70 (31.3) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Single | 72 (32.1) |

| Cohabiting or married | 104 (46.4) |

| Living alone (widowed/divorced/separated) | 48 (21.4) |

| In employment, n (%) | |

| Yes | 171 (76.3) |

| No | 53 (23.7) |

| History of alcohol/substance abuse, n (%) | 6 (2.7) |

| Family history of mental illnesses, n (%) | |

| Depression | 21 (10.1) |

| Other mental disorders | 37 (16.6) |

| Clinical data | |

| Diagnosis | |

| Major depressive disorder, n (%) | |

| First episode | 117 (52.2) |

| Recurrent episode | 81 (36.2) |

| Dysthymic disorder | 26 (11.6) |

| HAMD-17 | |

| HAMD, mean (SD) (at baseline, n=346) | 24.24 (6.55) |

| HAMD at 3-month follow-up, mean (SD) (n=224) | 10.08 (8.51) |

| Number of patients in remission at 3-month follow-up, n (%) | 114 (50.9) |

| Quality of life | |

| EQ-5D at baseline, mean (SD) (n=346) | 0.50 (0.21) |

| EQ-5D at 3-month follow-up, mean (SD) (n=224) | 0.724 (0.23) |

| EQ-5D at 6-month follow-up, mean (SD) (n=167) | 0.66 (0.23) |

| Visual analog scale for EQ-5D at the baseline, mean (SD) (n=346) | 52.36 (21.08) |

| Visual analog scale for EQ-5D at 3-month follow-up, mean (SD) (n=224) | 75.72 (13.87) |

| Visual analog scale for EQ-5D at 6-month follow-up, mean (SD) (n=167) | 67.74 (17.85) |

| Antidepressant, n (%) | |

| Serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) | 165 (73.6) |

| Serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) | 14 (6.3) |

| Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NASSAs) | 17 (7.6) |

| Tricyclic | 8 (3.6) |

| Others (eg, tetracyclic, selective serotonin reuptake enhancer [SSRE]) | 20 (8.9) |

| Hypnotic-sedatives, n (%) | |

| Trazodone | 32 (14.3) |

| Benzodiazepine | 171 (76.3) |

| Others | 21 (9.4) |

Abbreviations: HAMD, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2.

The dosage of main antidepressants used in this study

| Antidepressant | n | Mean dose (mg) (min–max) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoxetine | 118 | 24.83 (10–60) | 10.7 |

| Sertraline | 32 | 50.78 (25–100) | 13.4 |

| Escitalopram | 14 | 11.43 (5–20) | 4.6 |

| Venlafaxine | 11 | 88.64 (37.5–150) | 34.7 |

| Desvenlafaxine | 1 | – | – |

| Nortriptyline | 5 | 47 (25–75) | 25.9 |

| Mianserin | 6 | 27.5 (10–60) | 17.9 |

| Mirtazapine | 11 | 23.84 (7.5–45) | 11.1 |

| Tianeptine | 2 | 24.5 (12.5–37.5) | 17.7 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

According to HAMD, all the participants reported between 0 and 17 residual symptoms, with ~80% reporting between 0 and 10. The largest proportion of patients reported 7 symptoms (9.8%), but most (60.3%) were found to have between 3 and 7 (median =6).

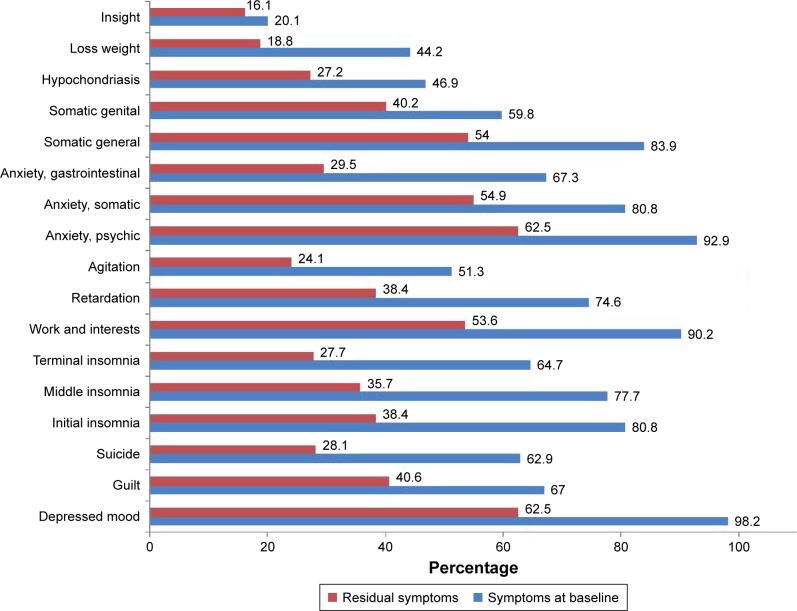

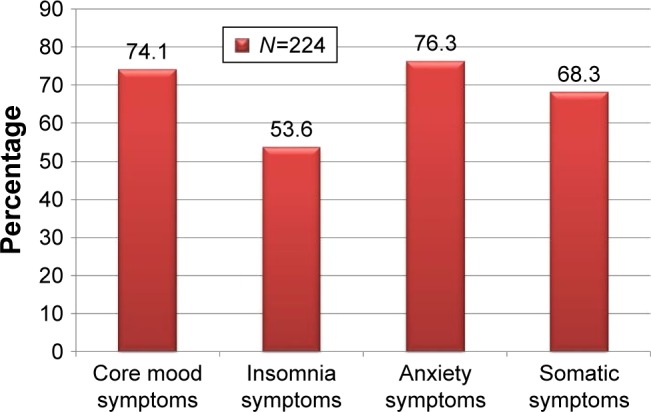

Depression and anxiety (psychological) symptom domains were the most common residual symptom domains found (62.5%) as shown in Figure 1. Among all the patients, 93.3% of them were experiencing at least one residual symptom, and when assembling the residual symptoms into groups, the most common symptoms domains were core mood symptoms (74.1%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.68–0.80), insomnia symptoms (53.6%; 95% CI, 0.47–0.60), anxiety symptoms (76.3%; 95% CI, 0.71–0.82), and somatic symptoms (68.3%; 95% CI, 0.63–0.74) as demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of residual symptoms when compared to baseline symptoms (N=224).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of residual symptoms domains.

At the 3-month follow-up, 50.9% (114 out of 224) of the patients were in remission. Table 3 shows the prevalence of residual symptoms according to remission status at the 3-month follow-up.

Table 3.

Prevalence of residual symptoms domains according to remission status at 3 months postbaseline

| Residual symptoms | Nonremission (%) | Remission (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Core mood symptoms | 92.5 | 42.7 |

| Insomnia symptoms | 72.4 | 27.0 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 98.5 | 44.9 |

| Somatic symptoms | 91.0 | 34.8 |

Prediction of relapse after 6 months

Relapse was defined as an HAMD score of >7 after having gone into remission within the 6-month period. Among the 114 remitted cases, 44 (38.6%) of them relapsed within 6 months. Table 4 shows the results of logistic regression analysis, in which residual insomnia symptoms were significantly associated with a within-6-month relapse (odds ratio [OR] =5.290, 95% CI, 1.42–19.76).

Table 4.

Summary logistic regression analysis results for residual symptoms predicting a relapse within 6 monthsa

| Residual symptoms | B | SE | Wald | P-value | OR | 95% CI

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Core mood symptoms | 0.317 | 0.691 | 0.210 | 0.647 | 1.373 | 0.354 | 5.316 |

| Insomnia symptoms | 1.666 | 0.672 | 6.140 | 0.013 | 5.290 | 1.416 | 19.758 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 0.464 | 0.702 | 0.437 | 0.509 | 1.590 | 0.402 | 6.290 |

| Somatic symptoms | −0.064 | 0.589 | 0.012 | 0.539 | 0.653 | 0.168 | 2.541 |

Note:

Controlling for age, sex, education, and marital status and employment status.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Impact on quality of life predicted by residual symptoms present at the 6-month follow-up

The results of a linear regression analysis show that EQ-5D scores at the baseline significantly predicted the EQ-5D scores at 6-month follow-up (B =0.477, 95% CI, 0.328–0.626), and particularly those for residual core mood and insomnia symptoms (B =−2.670, 95% CI, −0.181 to −0.027; B =−3.109, 95% CI, −0.172 to −0.038, respectively). The same analysis was carried out using the VAS of EQ-5D, but none of the results was found to be a significant predictor as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of linear regression results for residual symptoms predicting the EQ-5D score at 6 month postbaselinea,b

| Clinical variables | Unstandardized coefficients

|

t | P-value | 95% confidence interval for B

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Std error | Lower bound | Upper bound | |||

| EQ-5D score at the baseline | 0.477 | 0.075 | 6.329 | <0.001 | 0.328 | 0.626 |

| Residual mood symptoms | −0.104 | 0.039 | −2.670 | 0.008 | −0.181 | −0.027 |

| Residual insomnia symptoms | −0.105 | 0.034 | −3.109 | 0.002 | −0.172 | −0.038 |

| Residual anxiety symptoms | −0.045 | 0.042 | −1.066 | 0.288 | −0.127 | 0.038 |

| Residual somatic symptoms | 0.012 | 0.036 | 0.344 | 0.732 | −0.059 | 0.084 |

Notes:

Adjusted R square (R2adj) =0.34.

Controlling for age, sex, education level, and marital status and employment status. Bold type = P<0.01.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of residual symptoms among the study of depressive patients and their effects in terms of relapse rates and quality of life. The relapse rate found in this study was 38.6%, which is similar to those found in previous studies.13–15

The two most common residual symptoms domains found in this study were residual anxiety and core mood symptoms, a result similar to that of Romera et al.2 However, other studies have reported sleep and somatic symptoms as the most common residual symptoms domain found.4,16 These different results might have arisen due to variations in the methods used to measure for residual depressive symptoms, cultural and population differences.

After the 6-month follow-up in this study, regression analysis shows that any relapse into depression was significantly associated with the presence of residual insomnia symptoms. This result emphasizes the highly complex connection between depression and sleep symptoms, and that treating insomnia may represent an opportunity to prevent depressive illnesses from occurring/recurring.17,18

Residual symptoms are also associated with other negative outcomes, including a poor quality of life.6 In this study, the quality of life score found at the baseline, the residual core mood, and the insomnia symptoms significantly predicted the quality of life in the follow-up period, with an adjusted R2 for the linear regression analysis coming out at 0.34. Our results also emphasize the importance of residual insomnia; that it not only plays a vital role with regard to relapse but also in terms of quality of life as a whole. In this study, somatic symptoms were not found to be a predictor, as was the case in Woo et al’s study.7 Residual symptoms other than somatic symptom were not investigated in their study. It is interesting to note that the EQ-5D score in our study was in the same range as other studies focused on depressive disorder patients.19,20

When comparing the present study’s EQ-5D scores at the baseline and at the 6-month follow-up with those of other studies, the results here were aligned with those reported by Sobocki et al.21 When compared to Woo et al’s study,7 meanwhile, our EQ-5D scores were only a little lower (0.57 at the baseline and 0.77 at the 6-month follow-up), even though the changes in EQ-5D scores were found to be significantly different across the two studies. In Sapin et al’s study,22 the EQ-5D score was much lower at the baseline (0.33), rising to 0.68 at a 2-month follow-up. It is noticeable that in Sapin et al’s study,22 the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) was utilized to determine remission status. Overall, the EQ-5D score at the baseline and its change over time varied between the studies, even though it is a standardized tool. This variation may have been due to the measurement tool used, the cutoff score used for determining remission, and a number of other factors.

The results of this study show that it is very important for clinicians to be mindful of residual symptoms when treating depressive disorders, and especially core mood and insomnia, otherwise such symptoms may lead to a poorer quality of life among patients in the long run.

This study did have some limitations. First, the patient population used in this study was receiving treatment in psychiatric clinics, so the results may not be generalized to other types of depressive patient, such as those under primary care. Second, this is a short-term study to find out the impact of residual symptoms on relapse and quality of life, so the long-term study is required for deeper understanding. Third, this study did not include the patients who were admitted, which might make sense of the influence of residual symptoms.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multicentered study of depressed patients to have been carried out among Thais, and the study’s outcomes indicate that the proper treatment of depression should be a key aim of the Thai medical establishment in the future.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), and was coordinated and supported by the Medical Research Network of the Consortium of Thai Medical School (MedResNet). Additional funding for the research was provided by the Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University.

We would like to thank the following site investigators who critically reviewed the study proposal and collected data: Usaree Srisutasanavong (Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand), Peeraphon Lueboonthavatchai (Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand), Raviwan Nivataphand (Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand), Nattaporn Apisiridej (Trang Hospital, Trang, Thailand), Donruedee Petchsuwan (Trang Hospital, Trang, Thailand), Thawanrat Srichan (Lampang Hospital, Lampang, Thailand), Ruk Ruktrakul (Lampang Hospital, Lampang, Thailand), Anakevich Temboonkiat (Department of Psychiatry and Neurology, Phramongkutklao Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand), Namtip Tubtimtong (Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Pitsanulok, Thailand), Sukanya Rakkhajeekul (Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, Naresuan University, Pitsanulok, Thailand), and Boonsanong Wongtanoi (Srisangwal Hospital, Mae Hong Son, Thailand). The authors are also grateful to everyone who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this study.

References

- 1.Zajecka J, Kornstein SG, Blier P. Residual symptoms in major depressive disorder: prevalence, effects, and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):407–414. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12059ah1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Romera I, Pérez V, Ciudad A, et al. Residual symptoms and functioning in depression, does the type of residual symptom matter? A post-hoc analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman M, Martinez J, Attiullah N, Friedman M, Toba C, Boerescu DA. How should residual symptoms be defined in depressed patients who have remitted? Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(2):91–96. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClintock SM, Husain MM, Wisniewski SR, et al. Residual symptoms in depressed outpatients who respond by 50% but do not remit to antidepressant medication. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(2):180–186. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31820ebd2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fava M, Ball S, Nelson JC, et al. Clinical relevance of fatigue as a residual symptom in major depressive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(3):250–257. doi: 10.1002/da.22199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferguson M, Dennehy EB, Marangell LB, Martinez J, Wisniewski SR. Impact of fatigue on outcome of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor treatment: secondary analysis of STAR*D. Curr Med Res Opin. 2014;30(10):2109–2118. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2014.936553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woo JM, Joen HJ, Noh E, et al. Importance of remission and residual somatic symptoms in health-related quality of life among outpatients with major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12:188. doi: 10.1186/s12955-014-0188-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wongpakaran T, Wongpakaran N, Pinyopornpanish M, et al. Baseline characteristics of depressive disorders in Thai outpatients: findings from the Thai Study of Affective Disorders. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:217–223. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S56680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lotrakul M, Sukanich P, Sukying C. The validity and reliability of the Hamilton Rating scale for depression, Thai version. J Psychiatric Assoc Thail. 1996;41:235–246. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–343. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hounsome N, Orrell M, Edwards RT. EQ-5D as a quality of life measure in people with dementia and their carers: evidence and key issues. Value Health. 2011;14(2):390–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dombrovski AY, Cyranowski JM, Mulsant BH, et al. Which symptoms predict recurrence of depression in women treated with maintenance interpersonal psychotherapy? Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(12):1060–1066. doi: 10.1002/da.20467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Young D, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K. Severity classification on the Hamilton depression rating scale. J Affect Disord. 2013;150(2):384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borges S, Chen YF, Laughren TP, et al. Review of maintenance trials for major depressive disorder: a 25-year perspective from the US Food and Drug Administration. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(3):205–214. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seemüller F, Meier S, Obermeier M, et al. Three-year long-term outcome of 458 naturalistically treated inpatients with major depressive episode: severe relapse rates and risk factors. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264(7):567–575. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0495-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tranter R, O’Donovan C, Chandarana P, Kennedy S. Prevalence and outcome of partial remission in depression. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2002;27(4):241–247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lustberg L, Reynolds CF. Depression and insomnia: questions of cause and effect. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4(3):253–262. doi: 10.1053/smrv.1999.0075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falussy L, Balla P, Frecska E. Relapse and insomnia in unipolar major depression. Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 2014;16(3):141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steinert C, Hofmann M, Kruse J, Leichsenring F. Relapse rates after psychotherapy for depression – stable long-term effects? A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2014;168:107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peselow ED, Tobia G, Karamians R, Pizano D, IsHak WW. Prophylactic efficacy of fluoxetine, escitalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, and concomitant psychotherapy in major depressive disorder: outcome after long-term follow-up. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(3):680–686. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sobocki P, Ekman M, Ågren H, et al. Health-related quality of life measured with EQ-5D in patients treated for depression in primary care. Value Health. 2007;10(2):153–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2006.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sapin C, Fantino B, Nowicki ML, Kind P. Usefulness of EQ-5D in assessing health status in primary care patients with major depressive disorder. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:20. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]