Abstract

Background.

While health systems are striving for patient-centered care, they have little evidence to guide them on how to engage patients in their care, or how this may affect patient experiences and outcomes.

Objective.

To explore which specific patient-centered aspects of care were best associated with depression improvement and care satisfaction.

Methods.

Design: observational. Setting: 83 primary care clinics across Minnesota. Subjects: Primary care patients with new prescriptions for antidepressants for depression were recruited from 2007 to 2009. Outcome measures: Patients completed phone surveys regarding demographics and self-rated health status and depression severity at baseline and 6 months. Patient centeredness was assessed via a modified version of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care. Differences in rates of remission and satisfaction between positive and negative responses for each care process were evaluated using chi-square tests.

Results.

At 6 months, 37% of 792 patients ages 18–88 achieved depression remission, and 79% rated their care as good-to-excellent. Soliciting patient preferences for care and questions or concerns, providing treatment plans, utilizing depression scales and asking about suicide risk were patient-centered measures that were positively associated with depression remission in the unadjusted model; these associations were mildly weakened after adjustment for depression severity and health status. Nearly all measures of patient centeredness were positively associated with care ratings.

Conclusion.

The patient centeredness of care influences how patients experience and rate their care. This study identified specific actions providers can take to improve patient satisfaction and depression outcomes.

Key words: Anti-depressive agents, depression, primary health care, patient-centered care, patient satisfaction, patient care management.

Introduction

Growing interest in patient-centered care stems from recognizing the need to provide care that respects and responds to patient preferences, needs and ideals (1). The Institute of Medicine’s 2001 report on healthcare quality in the U.S. identified patient centeredness as one of six aims for ‘a new health system for the 21st century’ (1). Those six aims have now been consolidated into three in the Triple Aim, the target for most healthcare improvement efforts (2). Despite this increasing emphasis on patient centeredness, however, providers can be left wondering how to truly achieve patient-centered care.

Caring for patients with depression provides an excellent opportunity for clinicians to fully engage patients in their treatment. Depression is commonly diagnosed and treated in primary care settings, and patient preferences are critical in treatment decisions (psychotherapy versus antidepressants versus no treatment), determining how to involve family members or other supports and deciding between specific antidepressants or types of psychotherapy. Further, patient preferences and attitudes have a particularly strong influence on acceptance of and adherence to treatment in depression care (3). However, while many studies have examined the efficacy and effectiveness of antidepressant medications or psychotherapy in randomised trials, less is known about how to engage patients in these decisions, and how this engagement affects patient experiences and outcomes. This study provides a naturalistic, descriptive and exploratory examination of patient centeredness and depression outcomes in the primary care of patients with depression, with the goal of providing more specific and actionable information to clinicians and care systems.

Methods

Setting

A total of 792 patients received care in 83 primary care clinics representing 23 different medical groups in urban and rural areas across Minnesota. Data were part of baseline data collected from September 2007 through September 2009, prior to implementation of a statewide initiative to implement the collaborative care model for depression; i.e. patients were receiving usual care for their depression prior to any implementation of collaborative care (4). This study was reviewed, approved, and monitored by the local Institutional Review Boards.

Participants

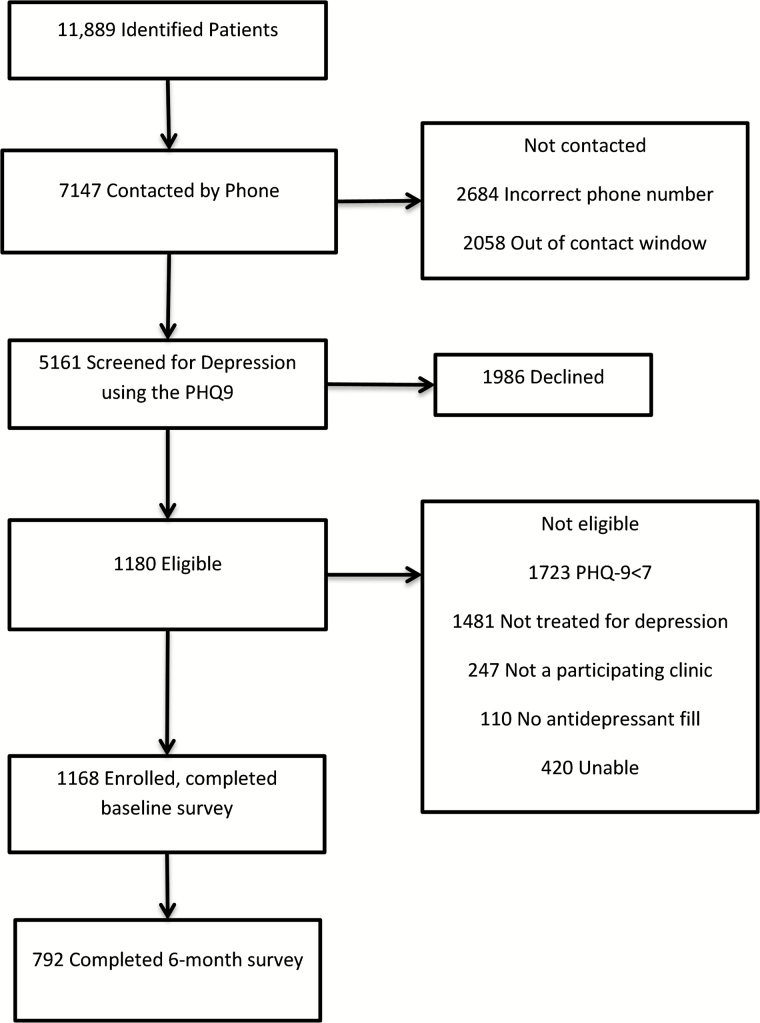

In all, 11889 patients were identified by their insurance carriers as having filled a prescription for an antidepressant medication from September 2007 through September 2009. Insurance payers provided weekly contact information for members from participating clinics who filled antidepressant prescriptions, and a central survey center conducted phone surveys with patients at baseline and again at 6 months. Of the 11 889 patients identified by insurance payers, 2684 had incorrect contact information and 2451 could not be reached within the 21-day window required to ensure baseline assessment before major effects from treatment. The participation rate of those contacted and potentially eligible was 37%. Figure 1 displays further recruitment details. A total of 1168 patients completed baseline phone surveys, and 68% (792) of those patients completed 6-month follow-up phone surveys, both of which included a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (5).

Figure 1.

Study patient flow diagram.

Usual care for depression

Patients received usual care for their depression in their primary care clinics, prior to any implementation of the collaborative care initiative. Clinics were not systematically screening patients for depression, and patients were primarily diagnosed during the routine course of clinic visits. Patients could be co-managed for depression by therapists or psychiatrists as part of their usual care.

Measures

Phone surveys included patient self-report questionnaires and were conducted by a central survey center at baseline and again at 6 months. These surveys provided information on patient demographics, health status (a single item asking patients to rate their overall health (6)), depression severity, and past and current depression episodes and treatment.

During these phone surveys, patients also completed an extension and adaptation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) (7) specific to depression care, informed by literature in this area and the team’s expertise in implementing related interventions. This modified PACIC was designed to measure how patient-centered, proactive, planned and collaborative patients viewed their depression care in the previous month using 14 dichotomous questions.

Depression severity was self-rated using the PHQ-9; scores of 7–9 indicated mild depression, 10–14 moderate, 15–19 moderately severe, and >20 severe (5,8). Remission was defined as achieving a PHQ-9 score of <5 (5).

Depression care quality was assessed by a single item that asked, ‘over the past month, how would you rate the quality of care you have received for depression at your primary care clinic?’ Patients could choose between excellent, very good, good, fair or poor.

Data analysis

Baseline characteristics were described as frequency distributions. The rate of remission at 6 months was estimated for positive and negative responses for each care process item. Similarly, the percent satisfied with the care process was estimated for positive and negative responses for each care process item. Both analyses were repeated while adjusting for PHQ-9 score and health status. We evaluated the differences in rates of remission (and satisfaction) between positive and negative responses for each care process item using chi-square tests. Statistical significance was defined as p<.05.

Results

A total of 792 patients between ages 18 and 88 (with a mean age of 47) received usual care for depression in primary care and completed baseline and follow-up surveys (Table 1). Seventy-five percent of patients were women, and a majority was white. Most had at least some college education and a household income at least 2 standard deviations above the federal poverty level. Overall, 68% of patients were insured by commercial insurance, 23% by state programs, 5% by Medicare and 3% by other insurance types (insurance type not included in table or model). At baseline, 32% of patients had mild depression, 40% moderate, 20% moderately severe and 8% severe. Patients’ experience of previous episodes of depression varied, with 37% experiencing their first episode, 23% their second and 38% at least their third. As part of their usual care of depression, 5% of patients were receiving outpatient psychiatric care, 3% group counseling and 25% individual therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with initial prescriptions of antidepressants for depression from September 2007 through September 2009

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <35 | 196 (25%) |

| 35–49 | 273 (35%) |

| 50–64 | 251 (32%) |

| 65+ | 72 (9%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 591 (75%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 711 (90%) |

| Hispanic | 62 (8%) |

| Other | 19 (2%) |

| Relationship status | |

| Coupled | 486 (61%) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 208 (26%) |

| Some college or technical school | 313 (40%) |

| College graduate | 271 (34%) |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 532 (67%) |

| Income | |

| >2× the poverty level | 544 (69%) |

| Self-rated Health | |

| Excellent/very good/good | 573 (72%) |

| Fair/Poor | 219 (28%) |

| % Life impaired due to health | |

| 50% or more | 455 (57%) |

| PHQ-9 score | |

| 7–9 | 255 (32%) |

| 10–14 | 315 (40%) |

| 15–19 | 161 (20%) |

| 20+ | 61 (8%) |

| Times treated for depression in past | |

| 0 | 289 (37%) |

| 1 | 185 (23%) |

| 2+ | 300 (38%) |

| Also treated by a psychiatrist | |

| Yes | 43 (5%) |

| Also receiving individual counselling | |

| Yes | 201 (25%) |

| Also engaged in group therapy | |

| Yes | 26 (3%) |

N = 792.

At 6 months, 292 patients (37%) achieved remission from their depression, and 606 patients (79%) rated their care as good-to-excellent (Table 2). A majority of patients thought their providers had considered their values and goals (75%), completed a PHQ-9 (64%), were asked about drug and alcohol use (66%) or were asked about thoughts of self-harm (69%). Approximately half of patients reported having been asked about concerns regarding their depression care (58%), provided with a treatment plan for daily life (61%), or told about changes they could make to improve their depression (56%). Fewer than half of patients reported being asked for ideas or preferences for their care (38%), asked about side effects (42%), encouraged to attend community programs (24%), asked their preference for medications or counselling (33%), given written information about depression (34%), provided with a nurse to help with care (16%) or called to follow up on their treatment (11%).

Table 2.

Patient Report of Care Processes and Rates of Remission and Highly Rated Care at 6 months.

| All patients | Patients with remission from depression, unadjusted; N (% by row)a |

Difference; P value | Adjusted differenceb; adjusted P value | Patients who rated their quality of depression care as good-to- excellent, unadjusted; N (% by row)a |

Difference; P value | Adjusted differenceb; adjusted P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall outcome rates | 292/792 (37%) | 606/769 (79%) | |||||

| PACIC questions: during the past month, were you: | |||||||

| 1. Asked for your ideas and preferences regarding treatment? | |||||||

| Yes | 297 | 123/297 (41%) | 7%; 0.04 | 6%; 0.10 | 243/286 (85%) | 10%; 0.002 | 9%; 0.004 |

| No | 483 | 165/483 (34%) | 355/471 (75%) | ||||

| 2. Asked about your concerns and questions? | |||||||

| Yes | 457 | 184/457 (40%) | 8%; 0.03 | 6%; 0.07 | 369/441 (84%) | 12%; 0.0001 | 11%; 0.0004 |

| No | 324 | 105/324 (32%) | 229/317 (72%) | ||||

| 3. Sure that your doctor or nurse considered your values and goals when recommending treatments? | |||||||

| Yes | 593 | 226/593 (38%) | 6%; 0.16 | 4%; 0.37 | 483/576 (84%) | 22%; <0.0001 | 21%; <0.0001 |

| No | 185 | 60/185 (32%) | 110/179 (62%) | ||||

| 4. Provided with a treatment plan you could do in your daily life? | |||||||

| Yes | 480 | 191/480 (40%) | 8%; 0.04 | 5%; 0.13 | 390/469 (83%) | 13%; 0.0002 | 10%; 0.0008 |

| No | 303 | 98/303 (32%) | 140/210 (70%) | ||||

| 5. Asked about any problems or side effects from your treatments? | |||||||

| Yes | 329 | 125/329 (38%) | 2%; 0.59 | 0%; 0.93 | 274/320 (86%) | 12%; <0.0001 | 11%; 0.0002 |

| No | 457 | 165/457 (36%) | 326/443 (74%) | ||||

| 6. Encouraged to attend programs in the community that could help you? | |||||||

| Yes | 190 | 70/190 (37%) | 0%; 0.97 | 1%; 0.86 | 156/183 (85%) | 8%; 0.01 | 8%; 0.02 |

| No | 597 | 219/597 (37%) | 445/581 (77%) | ||||

| 7. Told about changes you could make in your daily life that could improve depression (e.g. exercise)? | |||||||

| Yes | 443 | 167/443 (38%) | 2%; 0.54 | 1%; 0.73 | 356/431 (83%) | 9%; 0.002 | 9%; 0.004 |

| No | 343 | 122/343 (36%) | 244/332 (74%) | ||||

| 8. Asked to complete a brief depression scale like the one we used earlier? | |||||||

| Yes | 509 | 204/509 (40%) | 9%; 0.01 | 8%; 0.03 | 415/496 (84%) | 15%; <0.0001 | 14%; <0.0001 |

| No | 273 | 84/273 (31%) | 182/263 (69%) | ||||

| 9. Asked about your use of alcohol and drugs? | |||||||

| Yes | 521 | 195/521 (37%) | 1%; 0.76 | 0%; 0.98 | 408/506 (81%) | 6%; 0.09 | 5%; 0.14 |

| No | 259 | 94/259 (36%) | 189/251 (75%) | ||||

| 10. Asked about thoughts of hurting yourself or of suicide? | |||||||

| Yes | 549 | 219/549 (40%) | 10%; 0.008 | 9%; 0.02 | 434/534 (81%) | 8%; 0.007 | 8%; 0.01 |

| No | 237 | 71/237 (30%) | 166/229 (73%) | ||||

| 11. Asked whether you preferred medications or counseling? | |||||||

| Yes | 260 | 99/260 (38%) | 2%; 0.65 | 0%; 0.96 | 211/251 (84%) | 8%; 0.01 | 7%; 0.02 |

| No | 519 | 189/519 (36%) | 383/505 (76%) | ||||

| 12. Given written information about depression/treatment? | |||||||

| Yes | 270 | 102/270 (38%) | 2%; 0.70 | 1%; 0.80 | 223/263 (85%) | 10%; 0.003 | 9%; 0.003 |

| No | 511 | 186/511 (36%) | 373/495 (75%) | ||||

| 13. Provided with a nurse or other professional who works with your doctor to help you with depression care? | |||||||

| Yes | 129 | 45/129 (35%) | 2%; 0.62 | 4%; 0.39 | 110/126 (87%) | 10%; 0.01 | 9%; 0.02 |

| No | 659 | 245/659 (37%) | 492/639 (77%) | ||||

| 14. Called by a health professional who works with your doctor to follow up on how your treatments were coming? | |||||||

| Yes | 84 | 30/84 (36%) | 1%; 0.84 | 1%; 0.83 | 73/84 (87%) | 9%; 0.05 | 9%; 0.05 |

| No | 703 | 259/703 (37%) | 528/680 (78%) | ||||

N = 792. Differences in rates between positive and negative responses for rates of remission and for rates of high quality depression care ratings were evaluated using a chi-square test.

aPercentages by row; some rows have missing values.

bModel adjusted for PHQ-9 score and health status at baseline.

Five measures of patient centeredness were associated with remission at 6 months in the unadjusted model. These were having been: (i) asked for ideas and preferences regarding treatment (difference (d)= 7%, P = 0.04), (ii) asked about concerns or questions (d = 8%, P = 0.03), (iii) provided with a treatment plan for daily life (d = 8%, P = 0.04), (iv) asked to complete a depression screen (d = 9%, P = 0.01) and (v) asked about thoughts of suicide or self-harm (d = 10%, P = 0.008). However, the associations between depression remission and all of these patient-centered measures were somewhat weakened after adjustment for baseline PHQ-9 and health status, and having been asked for ideas and preferences, asked about concerns and questions or provided with a treatment plan were no longer significantly associated with remission after adjustment.

All measures of patient centeredness were positively associated with good-to-excellent care ratings in both the unadjusted and adjusted models (differences in the unadjusted model ranged from 8 to 22%; P values ranged from <0.0001 to 0.02) except for being asked about drug and alcohol use and being called by a health professional to follow up on treatment. The five measures most strongly associated with high care quality ratings in the unadjusted model were: (i) having been asked about concerns or questions (d = 12%, P = 0.0001), (ii) feeling that providers considered one’s values and goals (d = 22%, P < 0.0001), (iii) having been provided with a treatment plan for daily life (d = 13%, P = 0.0002), (iv) having been asked about side effects (d = 12%, P < 0.0001) and (v) having been asked to complete a depression scale (d = 15%, P < 0.0001).

Discussion

Patients had mixed views on how patient-centered their depression care was, with some aspects of patient-centered care reported relatively frequently, and others rarely. Patient satisfaction was significantly associated with almost all patient-centered measures. In contrast, only a few specific patient-centered measures were significantly associated with depression remission.

Given that patient satisfaction is increasingly incorporated into reimbursement and quality assessment measures, it is important to note that when patients were provided patient-centered care, they were much more likely to rate their care highly. This is admittedly not all that surprising, as patient satisfaction has been the dominant metric used to measure patient-centered care, and, indeed, our findings were consistent with a recent systematic review that found that patient-centered care was often associated with higher patient satisfaction (9). By its very definition, patient-centered care should provide care that is compassionate, empathetic, and responsive to each patient’s needs as he or she defines it (1), which should logically lead to patients feeling more satisfied that their needs have been met. In part, focusing on patient-centered care is thought to improve the quality of the doctor-patient relationship, leading patients to feel more engaged in the care process and comfortable with plans for treatment (10). All of these factors contribute to improved patient satisfaction.

Five patient-centered measures were associated with remission from depression in the unadjusted model, and these could be incorporated into practice by providers looking to improve depression outcomes for their patients. Specifically, when providers asked patients about their preferences for care, asked about concerns or questions, provided patients with a treatment plan, used a depression scale or asked patients about their suicide risk, patients’ depressive symptoms were significantly more likely to remit at 6 months.

Asking about thoughts of self-harm may have improved rapport with patients by giving providers a chance to express their concern for patients, or, alternatively, it may be that providers who felt comfortable screening for suicide risk already had a closer therapeutic alliance with their patients. It may also be the case that a primary care provider who was primarily responsible for treatment of a patient’s depression had a closer therapeutic alliance with that patient than a primary care provider who was co-managing a patient’s depression with a mental health specialist. Having good rapport and a strong therapeutic alliance with patients has been associated with increased adherence (11), which may contribute to better depression remission rates at 6 months.

Additionally, providers could consider improving patient engagement by better soliciting treatment preferences, as this has previously been shown to increase patient adherence and satisfaction (12,13). Unfortunately, our results also suggest this isn’t being widely done. Only 38% of patients reported being asked for their treatment preferences, and only 33% reported being asked whether they preferred antidepressants or therapy. While it’s possible that providers did not elicit preferences for therapy because of the relative lack of access to therapy providers to whom to refer their patients, our findings are consistent with other studies that have found a low tendency of providers to elicit patient preferences for other conditions (14). Of note, despite these low rates of eliciting preferences, 75% of patients felt their provider considered their values and goals when recommending treatments. Subanalysis comparing results determining whether patients were asked for treatment preferences and whether patients were asked if they preferred medications or counseling indicated these two items were measuring distinct aspects of care (Kappa = 0.40). This suggests that while providers did not ask about preferences explicitly, most patients felt they were taking their values into account via different means.

It is surprising that many measures of patient-centered care were not associated with depression remission, and the reasons for this are unclear. A systematic review found mixed relationships between patient-centered care and clinical outcomes for patients receiving care for an array of conditions (9). More work needs to be done in this area, as little research on patient centeredness has evaluated mental health care specifically. Ultimately, our data suggest we cannot assume that most measures that improve satisfaction will also significantly improve depression outcomes. However, it is possible that certain subpopulations of patients most at risk of poor depression outcomes may derive greater benefit from increased patient-centered care than others. In a related paper examining patient-level predictors of a combined outcome of depression remission and response in this same sample of patients (15), we found that patients were significantly less likely to achieve remission/response if they self-rated their health as poor-to-fair or were unemployed, and were more likely to achieve depression remission/response if they were younger or had more mild depression. It may be possible that more consistently using depression scales and screening patients for suicide risk may help improve depression outcomes for these subpopulations of patients.

Our findings suggest that the PACIC may be a useful tool for evaluating patient-centered care in depression care, but more research is also needed in this area. The Institute of Medicine considers patient-centered care to be comprised of eight dimensions, including respect for patient preferences, information, medication communication, care coordination, emotional support, physical comfort, family involvement, continuity and transition, and access to care (1). Each question of the PACIC touches on one or more of these eight dimensions, and nearly all PACIC items were significantly associated with patient satisfaction. This is reassuring as we continue to move towards increased patient centeredness in clinical practice, but more evaluation of the PACIC specific to depression and other behavioural health conditions is needed. We are aware of only one other evaluation of the PACIC in patients with mental health issues in primary care, which found that the PACIC adequately captured the perception of chronic illness care by patients in Germany with mental illnesses, including depression (16). Further study of the PACIC would help providers and care systems better understand its role in evaluating patient-centered care for people with depression. In our study, PACIC items regarding soliciting patient preferences for care and questions or concerns, providing treatment plans, utilizing depression scales, and asking about suicide risk are actionable items that were positively associated with depression remission, and a pilot or cohort study focused on these patient-centered interventions may be merited.

Encouragingly, most providers asked patients about thoughts of suicide (69%) as well as drug and alcohol use disorders (66%), the latter of which is known to increase the risk of both depression and suicide (17,18). Use of depression screening instruments, such as the PHQ-9, may have prompted providers to ask about thoughts of self-harm, which could have contributed to relatively high rates of suicide screening. To this point, 64% of patients recall completing a depression screen at their primary care visit, and in subanalysis of these two measures, we found moderate agreement between them (Kappa = 0.58) suggesting some degree of overlap. Ultimately, regardless of what prompted providers to ask about suicide risk, patients who were asked were more likely to experience remission at 6 months.

We acknowledge several potential limitations to our study. Patients may have mistakenly recalled elements of their care, although we attempted to lessen this risk by contacting patients within 21 days of their first antidepressant prescription. Our sample included only patients started on antidepressant medications, and thus our results cannot be generalised to the experience of those patients who engaged only in therapy for their treatment or those who opted for no treatment. In our sample, 37% of patients achieved remission at 6 months, a rate similar to an estimated spontaneous rate of depression remission of 32% at 6 months in a study using data from wait-list controlled trials and observational cohort studies (19). These similar rates generate some uncertainty about how much depression remission in our study was related to patient-centered care, as opposed to the natural course of depression.

A large percentage of patents were lost to follow-up, which may have reduced the reliability of 6-month remission data and associations with other factors. In the DIAMOND final results paper (4), we assessed survey response bias by comparing patient characteristics of 6-month survey respondents with those of nonrespondents. This sample included patients who were receiving the DIAMOND collaborative care intervention, along with three comparison groups, one of which was the sample for this paper: primary care patients receiving usual care for depression prior to DIAMOND’s implementation. The final non-parsimonious response propensity model found that higher response propensities were associated with higher likelihoods of depression remission (P < 0.002) and higher functional health status (P < 0.001) at 6 months, potentially biasing our study away from the null hypothesis. A final limitation is that we present a large number of comparisons here, and this increases the risk that some of the associations we found may actually be random.

Conclusion

In summary, nearly all measures of patient-centered care were positively associated with patient care ratings, while specific measures of patient centeredness (soliciting patient preferences for care, asking about questions or concerns, providing treatment plans, utilizing depression scales and asking about suicide risk) were positively associated with depression remission. This study identifies specific actions providers can take to improve patient satisfaction and depression outcomes. Striving to incorporate these patient-centered measures should only further improve patient experience and care.

Declarations

Funding: National Institute of Mental Health (#5R01MH080692).

Ethical approval: This study was reviewed, approved and monitored by the local Institutional Review Boards

Conflict of interest: Leif Solberg is an associate editor of Family Practice. The remaining authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. The National Academies Press, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008; 27: 759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cooper LA, Gonzales JJ, Gallo JJ, et al. The acceptability of treatment for depression among African-American, Hispanic, and white primary care patients. Med Care 2003; 41: 479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Solberg LI, Crain AL, Maciosek MV, et al. A stepped-wedge evaluation of an initiative to spread the collaborative care model for depression in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2015; 13: 412–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DeSalvo KB, Bloser N, Reynolds K, He J, Muntner P. Mortality prediction with a single general self-rated health question. A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2006; 21: 267–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glasgow RE, Wagner EH, Schaefer J, Mahoney LD, Reid RJ, Greene SM. Development and validation of the Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC). Med Care 2005; 43: 436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012; 184: E191–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 2013; 70: 351–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saha S, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality. J Natl Med Assoc 2008; 100: 1275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thompson L, McCabe R. The effect of clinician-patient alliance and communication on treatment adherence in mental health care: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2012; 12: 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Martin LR, Williams SL, Haskard KB, Dimatteo MR. The challenge of patient adherence. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2005; 1: 189–99. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lin EH, Von Korff M, Katon W, et al. The role of the primary care physician in patients’ adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care 1995; 33: 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davis K, Schoenbaum SC, Audet AM. A 2020 vision of patient-centered primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2005; 20: 953–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rossom RC, Solberg LI, Vazquez-Benitez G, et al. Predictors of poor response to depression treatment in primary care. Psychiatr Serv 2016; appips201400285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gensichen J, Serras A, Paulitsch MA, et al. The patient assessment of chronic illness care questionnaire: evaluation in patients with mental disorders in primary care. Commun Ment Health J 2011; 47: 447–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quello SB, Brady KT, Sonne SC. Mood disorders and substance use disorder: a complex comorbidity. Sci Pract Perspect 2005; 3: 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tondo L, Baldessarini RJ, Hennen J, et al. Suicide attempts in major affective disorder patients with comorbid substance use disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60:63–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Whiteford HA, Harris MG, McKeon G, et al. Estimating remission from untreated major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2013; 43:1569–85. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001717. Epub 2012 Aug 10. Review. PubMed PMID: 22883473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]