Abstract

Knowledge regarding cellular fusion and nuclear reprogramming may aid in cell therapy strategies for skeletal muscle diseases. An issue with cell therapy approaches to restore dystrophin expression in muscular dystrophy is obtaining a sufficient quantity of cells that normally fuse with muscle. Here we conferred fusogenic activity without transdifferentiation to multiple non–muscle cell types and tested dystrophin restoration in mouse models of muscular dystrophy. We previously demonstrated that myomaker, a skeletal muscle–specific transmembrane protein necessary for myoblast fusion, is sufficient to fuse 10T 1/2 fibroblasts to myoblasts in vitro. Whether myomaker-mediated heterologous fusion is functional in vivo and whether the newly introduced nonmuscle nuclei undergoes nuclear reprogramming has not been investigated. We showed that mesenchymal stromal cells, cortical bone stem cells, and tail-tip fibroblasts fuse to skeletal muscle when they express myomaker. These cells restored dystrophin expression in a fraction of dystrophin-deficient myotubes after fusion in vitro. However, dystrophin restoration was not detected in vivo although nuclear reprogramming of the muscle-specific myosin light chain promoter did occur. Despite the lack of detectable dystrophin reprogramming by immunostaining, this study indicated that myomaker could be used in nonmuscle cells to induce fusion with muscle in vivo, thereby providing a platform to deliver therapeutic material.—Mitani, Y., Vagnozzi, R. J., Millay, D. P. In vivo myomaker-mediated heterologous fusion and nuclear reprogramming.

Keywords: cell therapy, membrane fusion, muscular dystrophy

The muscular dystrophies (MDs) are a group of inherited muscle disorders caused by mutations in the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex, which provides stability for the muscle cell membrane (1). The most common form of MD is Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), which affects 1 in 3500 boys and is caused by a mutation in dystrophin that results in severe muscle wasting (2). The ideal treatment strategy for MD is to express a normal copy of the mutated gene by supplying exogenous dystrophin or by repairing the endogenous mutation. Exon-skipping approaches are currently in clinical trial for DMD therapy, and the CRISPR/Cas9 system was recently utilized to repair dystrophin mutations in the mouse (3–6). Introduction of exogenous dystrophin has proved difficult mainly because the dystrophin coding sequence is 13 kb, much larger than the packaging capacity of viral constructs typically used to transduce muscle. Nonetheless, adeno-associated virus–mediated delivery of truncated μ-dystrophin has shown efficacy to improve dystrophic muscle function (7, 8). Cellular approaches to restore dystrophin includes use of myogenic populations such as muscle stem cells, mesoangioblasts, and induced pluripotent stem cells; however, issues with these cells include difficulty of isolation, expansion ex vivo, and migration away from the site of injection after transplantation (9–13). Non–muscle cell types such as fibroblasts have also been proposed for use in MD cell therapy, but only after myogenic conversion through expression of MyoD (14). Taken together, although each of the numerous myogenic cell types tested for efficacy in MD exhibits potential, alternative strategies may be beneficial.

Skeletal muscle formation during development and regeneration requires fusion of myogenic progenitor cells (15). Detailed mechanisms that govern myoblast fusion are not fully elucidated; however, current data suggest myomaker plays a central role in this process. Myomaker is a skeletal muscle–specific transmembrane protein necessary for myoblast fusion and muscle formation (16, 17). We previously demonstrated that expression of myomaker in 10T 1/2 fibroblasts induced their fusion with myoblasts in culture, which highlighted a platform to force fusion of readily available nonmuscle cells with myofibers (16). If myomaker-expressing nonmuscle cells readily fuse to myofibers, their nuclei would require reprogramming to restore normal expression of the mutated protein that cause genetic muscle diseases, such as DMD. Specifically, because nonmuscle cells do not express dystrophin, once the nonmuscle nuclei are within the muscle fiber after fusion, the transcription factors required for dystrophin transcription would need to diffuse into the nonmuscle nucleus in sufficient quantity to activate dystrophin transcription.

Nuclear reprogramming has classically been studied through chemically induced heterokaryon formation. Heterokaryons formed between skeletal muscle cells and fibroblasts from different species resulted in activation of muscle genes from the fibroblast nuclei, suggesting a dominant effect of muscle nuclei (18, 19). Moreover, a chimeric protein formed between the fusogenic measles virus hemagglutinin glycoprotein and a fragment that recognized a muscle-specific integrin was sufficient to fuse human fibroblasts with mouse muscle (20). These chimeric myotubes also exhibited evidence of reprogramming in vitro that included detection of human myoD and myogenin. While reprogramming has been definitively observed in heterokaryons in vitro, the efficiency of this process in vivo is much less understood even though it represents a potential pathway for augmentation of genetic muscle diseases. Indeed, there are conflicting reports as to whether reprogramming occurs after engraftment of hematopoietic cells from a wild-type (WT) donor into dystrophic muscle; however, the amount of fusion observed is relatively low (21–23). Thus, even if nonmuscle cells could be engineered to robustly fuse to muscle, it remains to be determined whether nuclear reprogramming is a plausible mechanism to restore the expression of the deficient protein.

In this study, we enhanced the fusion capability of nonmuscle cells through myomaker expression and assessed subsequent nuclear reprogramming. We utilized mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), cortical bone stem cells (CBSCs), and tail-tip fibroblasts (TTFs). TTFs were chosen because of ease of isolation; we have shown that myomaker fibroblasts fuse to muscle in vitro. MSCs are an intriguing source of cells for muscle cell therapy because a sufficient supply can be obtained from bone marrow or adipose tissue (24–26). They also can be expanded easily in culture and display immunomodulatory properties that may aid in engraftment while minimizing rejection (27). Indeed, MSCs have been used in clinical trials for several inflammatory conditions, including diabetes, multiple sclerosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, myocardial infarction, and graft versus host disease (28). Similar to MSCs, CBSCs are of mesenchymal origin, except they are isolated from cortical bone (29). While much less is known about CBSCs compared to MSCs, both cells exhibit stability during cell culture expansion. One characteristic of CBSCs that was attractive for our purposes is that they may be less genetically mature compared to MSCs (30), suggesting CBSCs could be more amenable to reprogramming.

We found that MSCs, CBSCs, and TTFs fuse to muscle when they express myomaker. We also demonstrated that myomaker+ MSCs have the ability to fuse to both activated myoblasts during regeneration and uninjured myofibers. Moreover, we investigated dystrophin restoration through nuclear reprogramming in mdx4cv muscle in vitro and in vivo. Evidence for dystrophin reprogramming was observed in vitro; however, this phenomenon did not occur at immunohistochemically detectable levels in vivo, although an alternative reporter system allowed us to detect reprogramming of myosin light chain, a marker of mature muscle.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57BL/6 (WT), mdx4cv (002378; The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA), MyomakerLacZ/loxP; Pax7CreERT2 (myomakerscKO), Rosa26mTmG (007676; The Jackson Laboratory), Rosa26tdTomato (007905; The Jackson Laboratory), and myl1Cre/+ (024713; The Jackson Laboratory) mice were used as a source of cells and/or a recipient in cell transplantation studies. MyomakerscKO mice were generated as previously described (17, 31). Tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in corn oil with 10% ethanol at a concentration of 25 mg/ml and intraperitoneally administered at a dose of 0.075 mg/kg/d for 5 d. All animal procedures were approved by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International guidelines.

Cell preparation

WT MSCs were generated as described previously (32). Briefly, bone marrow cells were plated on fibronectin-coated wells (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium supplemented with 20% of MSC stimulatory supplements (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), 100 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 ng/ml human platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB, and 10 ng/ml recombinant mouse epidermal growth factor (EGF). Adherent clusters were grown for a minimum of 5 passages, and macrophage depletion was assessed by flow cytometry. WT MSCs were maintained in high-glucose DMEM (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% bovine growth serum (HyClone) and penicillin/streptomycin.

Membrane Tomato (mTom) CBSCs were isolated from Rosa26mTmG mice as described by others (30). This method was modified for isolation of CBSCs from myl1Cre/+ and WT mice. Femurs and tibias were collected and crushed with a mortar and pestle after removing epiphyses. Crushed bone was washed 5 times with PBS to remove marrow cells and minced into ∼2 mm fragments with a scalpel. After incubation in low-glucose DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 0.3% collagenase type I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1.5 h at 37°C, both bone fragments and cells were plated in low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 20% MSC stimulatory supplements, 30% Ham F10 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 100 μM 2-mercaptoethanol, 10 ng/ml mouse PDGF-BB (ProSpec, Des Plaines, IL, USA), 10 ng/ml mouse EGF (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), and 2.5 ng/ml human fibroblast growth factor–basic (bFGF; Thermo Fisher Scientific). After 7 d, the bone fragments were discarded, and the cells were trypsinized and expanded. CBSCs were maintained in low-glucose DMEM supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 40% Ham F-10, 10 ng/ml mouse EGF, 2.5 ng/ml human bFGF, and penicillin/streptomycin.

To obtain TTFs, adult tails from WT mice were skinned and cut into small pieces with a razor blade. The tail explants were plated on 100-mm culture dishes with high-glucose DMEM containing 10% bovine growth serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and the medium was changed every other day. Fibroblasts were allowed to migrate out of the tail explants for 7 to 10 d, then were trypsinized and plated for viral transduction.

Primary myoblasts were isolated from WT, myomakerscKO, or mdx4cv mice as described previously (33). Cells were plated on collagen-coated plates, maintained in growth medium (15% fetal bovine serum, 40% Ham F-10, and 2.5 ng/ml human bFGF in low-glucose DMEM with penicillin/streptomycin), and differentiated in differentiation media (2% horse serum in high-glucose DMEM with penicillin/streptomycin). WT and myomakerscKO primary myoblasts were infected with green fluorescent protein (GFP) or dsRED retrovirus for the infection of nonmuscle cells.

In vitro heterologous fusion

Nonmuscle cells were transduced with myomaker and/or GFP retrovirus as described previously (33). Briefly, plasmid DNA was transfected using FuGENE6 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) into Platinum E cells (Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA, USA), and virus medium was collected 48 h after transfection. After addition of polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich), the virus supernatant was incubated on the target cells for 18 h. The transduction efficiency of all nonmuscle cells, as assessed by immunostaining with a custom-generated myomaker antibody, was between 95 and 100% for all infections (unpublished observations). Primary myoblasts were plated on a collagen-coated plate at a density of 37,500 cells/cm2, and nonmuscle cells were added the next day at a density of 6250 cells/cm2 and cultured in differentiation medium. After 5 d, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100/PBS followed by blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin/PBS, then incubated with anti-myosin heavy chain (1:1000, clone MF20; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and/or anti-dystrophin antibodies (1:1000, ab15277; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (1:1000).

Cell transplantation

Cells were trypsinized and resuspended in PBS at a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml and kept on ice. Twenty-five microliters of the cell suspension (500,000 cells) was loaded into a Gastight syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV, USA) equipped with a 30-gauge needle, and the needle was longitudinally inserted from the distal to proximal end of a tibialis anterior (TA) muscle. Injection was performed by 5 consecutive motions per muscle, which consisted of a 5 µl injection approximately every 1 mm as the needle was removed. Where indicated, TAs were injured by injection of 10 µM cardiotoxin (CTX; 50 µl) 24 h before transplantation. For trichostatin A (TSA; ApexBio, Hsinchu City, Taiwan) treatment, an osmotic pump (0000298; Durect, Cupertino, CA, USA) was filled with 50% DMSO/15% ethanol containing 6 mg/ml TSA and implanted subcutaneously. Cells were also treated with 0.1 µM TSA for 24 h before transplantation. For intracardiac cell delivery, the heart was exposed via left thoracotomy and 5 × 104 GFP+ myomaker+ MSCs (suspended in 21 µl of sterile saline) were injected with a 33-gauge Hamilton syringe into 3 defined areas along the anterior wall of the left ventricle.

Muscle histology

Hindlimbs were dissected with TAs attached to the bone and immersed in 4% PFA/PBS for 1 to 2 h at 4°C. A subset of muscles was imaged in whole-mount with a Zeiss stereomicroscope (Carl Zeiss GmbH, Jena, Germany) to visualize tdTomato before removing the bone. The TA muscles were removed from the bone, cut into 2 pieces at the midbelly, and immersed in 2% PFA/PBS overnight at 4°C, then placed in 30% sucrose/PBS at 4°C. After 1 to 2 d, the muscles were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA, USA) and frozen, and 10-μm sections were collected. The sections were treated with permeabilizing/blocking solution (1% bovine serum albumin, 1% heat-inactivated goat serum, 0.025% Tween 20, and 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated with anti-dystrophin (1:200) and/or anti-laminin-2 (1:500, L-0663; Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies overnight at 4°C. The sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor secondary antibodies (1:1000) for 1 h at room temperature and mounted with VectaShield containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). For analysis of fusion in cardiac tissue, hearts were arrested in diastole via intracardiac injection of ice-cold 1 M KCl and perfused with 4% PFA/PBS. After 4 h of fixation in PFA/PBS, hearts were washed twice with PBS and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose/PBS overnight, and 5 µm cryosections were collected. All immunostaining in vitro and in vivo was visualized with a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope with A1R confocal running NIS Elements (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), and images were analyzed with Fiji (ImageJ, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) (34).

RNA analysis

Cells were lysed, and total RNA was extracted using RNAqueous-Micro Kit (AM1931; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and treated with DNase I. cDNA was synthesized using MultiScribe reverse transcriptase with random hexamer primers (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Myomaker expression was assessed using standard real-time quantitative PCR approaches with PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Analysis was performed on a 7900HT fast real-time PCR machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with the following primers: forward, 5′–ATCGCTACCAAGAGGCGTT–3′; reverse, 5′–CACAGCACAGACAAACCAGG–3′. Results were normalized using glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) with the following primers: forward, 5′–TGCGACTTCAACAGCAACTC–3′; reverse, 5′–GCCTCTCTTGCTCAGTGTCC–3′. Cre expression was assessed using standard PCR and gel electrophoresis with the following primers: forward, 5′–AGGTTCGTTCACTCATGGA–3′; reverse, 5′–TCGACCAGTTTAGTTACCC–3′. GAPDH expression was assessed as a reference gene with the same primers as noted above.

Quantification and statistical analysis

For quantitative assessment of in vivo fusion, the number of GFP+ or mTom+ myofibers in a representative section of each muscle was manually counted; data are presented as means ± sem. The data were analyzed by unpaired Student’s t test with GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Expression of myomaker in MSCs induces fusion with muscle

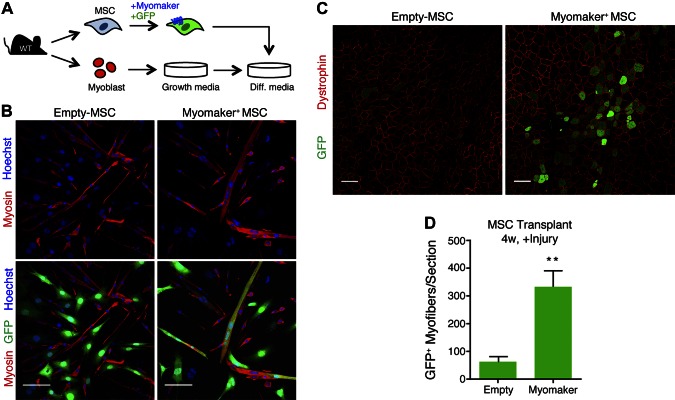

Previously we showed that myomaker-expressing 10T 1/2 fibroblasts fuse to primary myoblasts (16). To determine if MSCs are also amenable to myomaker-mediated fusion, we coinfected mouse MSCs with myomaker and GFP retroviruses. As a control, we also coinfected MSCs with empty and GFP retroviruses. GFP+ myomaker+ MSCs were then mixed with primary myoblasts from WT mice and differentiated for 5 d (Fig. 1A). Myoblasts were tracked through immunostaining with an antibody to myosin, a marker of muscle differentiation. We observed GFP+ myosin+ structures when myoblasts were mixed with myomaker+ MSCs indicating fusion between these cell populations (Fig. 1B). We did not observe GFP+ myosin− multinucleated cells, indicating that myomaker+ MSCs did not fuse to each other. GFP+ myosin+ cells were not readily detected in cultures containing cells not expressing myomaker (empty MSCs) and myoblasts (Fig. 1B). We next tested whether myomaker+ MSCs were able to fuse to muscle in vivo. The TA was injured with CTX, and the next day 500,000 GFP+ myomaker+ MSCs were transplanted into the TA. The presence of GFP within dystrophin+ myofibers indicated fusion of MSCs with muscle and was evaluated 4 wk after transplant. Minimal GFP+ myofibers were detected after transplantation of empty MSCs; however, an increase in heterologous fusion was observed with myomaker+ MSCs (Fig. 1C). Quantification of the number of GFP+ myofibers per section revealed a 5-fold increase in fusion of myomaker+ MSCs compared to empty MSCs (Fig. 1D). These results demonstrate that myomaker-expressing MSCs are fusion competent and that muscle is susceptible to heterologous fusion in an in vivo transplantation setting.

Figure 1.

In vitro and in vivo heterologous fusion of myomaker+ MSCs with muscle cells. A) Schematic of in vitro fusion study. MSCs were isolated from WT mouse bone marrow, transduced with myomaker and GFP retroviruses, and cocultured with WT primary myoblasts and differentiated. B) Cells were fixed after 5 d of differentiation and immunostained with a myosin antibody (red). Myomaker+ MSCs fused with myoblasts and formed chimeric myotubes (myosin+ GFP+). C) Representative muscle sections 4 wk after transplantation of MSCs into TA muscles of WT mice injured with CTX 24 h before transplantation. Sections were stained with dystrophin antibody (red) to identify myofibers. D) Quantification of number of GFP+ myofibers per section. Data are presented as means ± sem, n = 4 muscles. **P < 0.01 compared to empty. Scale bars, 100 µm.

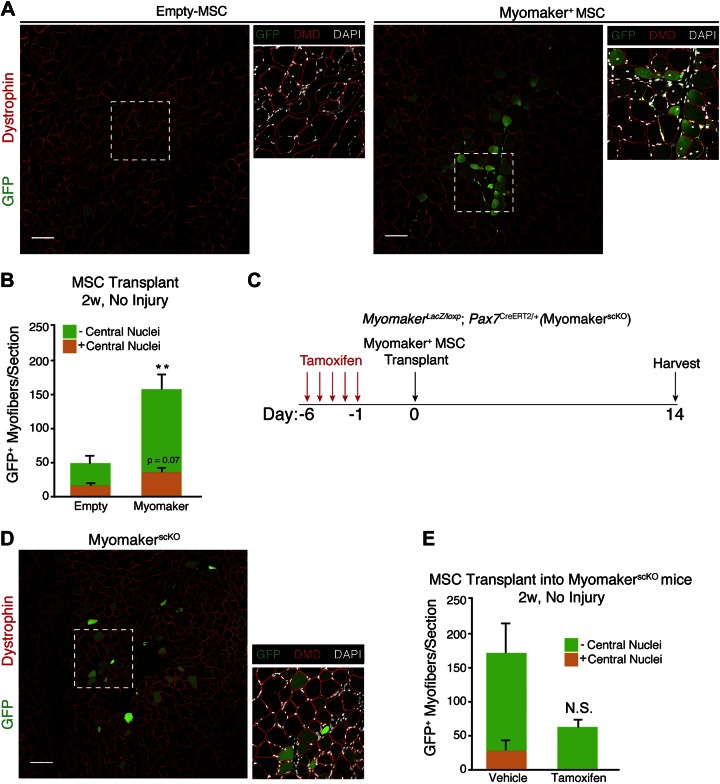

We next assessed whether myomaker+ MSCs were able to fuse to muscle in the absence of injury, which would suggest heterologous fusion could be utilized in nondystrophic disease settings where satellite cells are not activated. Injection of myomaker+ MSCs into uninjured TAs resulted in fusion with muscle, as depicted by GFP+ dystrophin+ myofibers (Fig. 2A). The ability of myomaker to fuse nonmuscle cells to muscle was specific to skeletal muscle because transplantation of myomaker+ MSCs into cardiac tissue did not result in extensive fusion (Supplemental Fig. 1). Central nuclei are a hallmark of regenerating muscle fibers and are therefore a surrogate for muscle progenitor activity (35). While the recipient muscles in this experiment were not injured with CTX, we speculate that the central nuclei observed is due to minor injury from the needle during cell transplantation. No obvious differences in total (GFP+ or GFP−) central nucleated myofibers were detected after transplantation of empty MSCs or myomaker+ MSCs, indicating myomaker+ MSCs do not enhance damage resulting from the needle injury (Fig. 2A, insets). However, GFP+ fibers with and without central nuclei were increased by 2- and 4-fold, respectively, in myomaker+ MSCs compared to empty MSCs, suggesting that myomaker confers fusion ability with mature myofibers and activated myoblasts (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Myomaker+ MSCs fuse with uninjured muscle. A) Representative muscle sections 2 wk after transplantation of MSCs into uninjured TA muscles of WT mice. GFP fluorescence was observed in both myofibers with and without central nuclei, suggesting myomaker+ MSCs fused with both regenerating and nonregenerating fibers. B) Quantification of GFP+ fibers per section with and without central nuclei after transplantation of myomaker+ MSCs into uninjured muscle; n = 4 muscles. **P < 0.01 compared to empty without central nuclei. C) Schematic of transplantation study using myomakerscKO mice. Satellite-cell-derived myomaker was deleted through treatment with tamoxifen for 5 consecutive days. D) Representative muscle sections 2 wk after transplantation of myomaker+ MSCs into uninjured TA muscles of myomakerscKO mice. Central nuclei were not observed in myomakerscKO mice, demonstrating inhibition of regeneration. E) Quantification of number of GFP+ fibers per section with and without central nuclei after transplantation into myomakerscKO muscle. NS, nonsignificant. n = 4–6 muscles. Data are presented as means ± sem. Scale bars, 100 µm.

Because transplantation of cells can induce muscle injury as a result of needle insertion, we inactivated the fusion ability of endogenous satellite cells through genetic deletion of myomaker to determine whether myomaker+ MSCs were able to fuse directly to myofibers. Conditional deletion of myomaker in satellite cells was achieved by utilizing mice containing a myomaker targeted allele (myomakerLacZ/loxP) and a Pax7CreERT2/+ allele that expresses Cre specifically in satellite cells. To make certain this approach was sufficient to generate myoblasts unable to fuse, we treated myomakerLacZ/loxP; Pax7CreERT2/+ mice with either vehicle (control) or tamoxifen (myomakerscKO), then isolated satellite cells from muscle 3 d after CTX injury. Myomaker expression was significantly reduced in myomakerscKO myoblasts, and these cells failed to fuse, highlighting the utility of this system to block fusion of satellite cells (Supplemental Fig. 2). MyomakerLacZ/loxP; Pax7CreERT2/+ mice were then treated with either vehicle or 5 doses of tamoxifen to delete myomaker in satellite cells and then were transplanted with myomaker+ MSCs (Fig. 2C). Myomaker+ MSCs displayed fusion competency even after endogenous satellite cells were rendered fusion incompetent, suggesting that they were able to fuse with myofibers (Fig. 2D). Quantification of fusion events with and without central nuclei indicates that myomaker+ MSCs indeed fuse to myofibers in the absence of satellite cell fusion activity (Fig. 2E). A nonstatistically significant reduction in GFP+ myofibers without central nuclei was observed in tamoxifen-treated samples compared to vehicle. This reduction may suggest that the number of centrally nucleated fibers is an underestimation and that some fibers without central nuclei may contain central nuclei above or below this plane of section.

We have demonstrated that cells not expressing myomaker (empty MSCs) are able to fuse with muscle, which suggests that fusion in vivo does not absolutely require myomaker on both cells. To further evaluate this concept, we generated WT-GFP myoblasts and myomaker knockout (KO)-dsRED myoblasts and transplanted them into WT mice after CTX-induced injury. Compared to myomaker KO-dsRED myoblasts, WT-GFP myoblasts exhibited greater engraftment potential (Supplemental Fig. 3). Moreover, we observed an increased number of small mononuclear dsRED+ cells, indicating that these cells were unable to fuse (Supplemental Fig. 3). We also transplanted WT-GFP myoblasts and myomaker KO-dsRED myoblasts together and observed predominantly GFP+ muscle fibers and not dsRED+ fibers, suggesting WT-GFP myoblasts are more fusion competent (Supplemental Fig. 3). Overall, these data indicate that both myoblast–myoblast fusion and nonmuscle–myoblast fusion can occur in vivo during muscle regeneration if at least 1 of the 2 cells expresses myomaker.

Dystrophin reprogramming of MSC nuclei after heterologous fusion

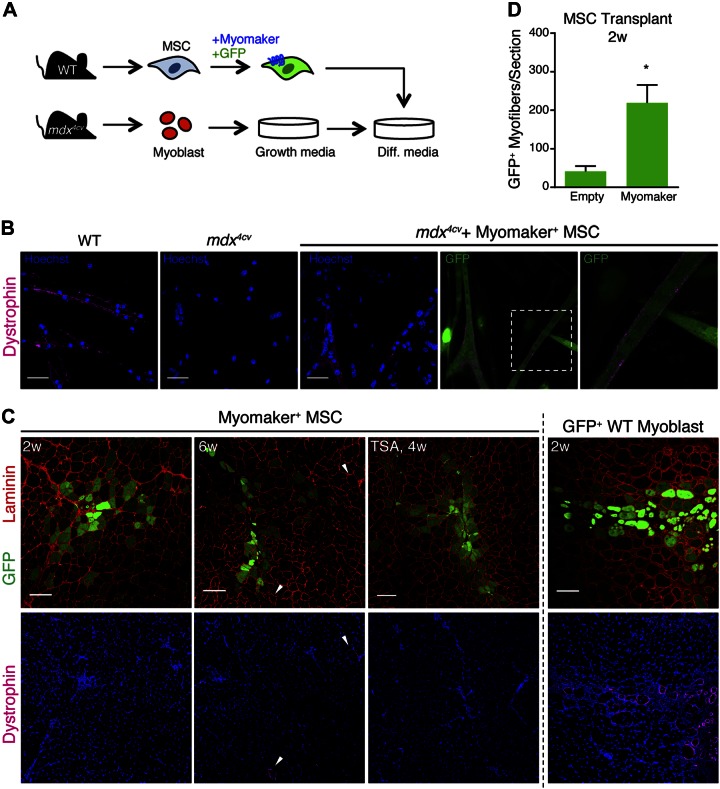

Because myomaker significantly enhances fusion of MSCs, we evaluated whether MSC nuclei were susceptible to reprogramming and able to restore dystrophin expression in mdx4cv myotubes. We isolated myoblasts from mdx4cv mice and cocultured them with GFP+ myomaker+ MSCs (Fig. 3A). After 5 d of differentiation, we evaluated fusion and dystrophin expression in these cultures. As expected, dystrophin was detected in myotubes derived from WT myoblasts but not mdx4cv myotubes (Fig. 3B). We observed fusion of myomaker+ MSCs with mdx4cv myoblasts and dystrophin expression along the membrane in some chimeric myotubes; however, most GFP+ myofibers were still dystrophin− (Fig. 3B). Because mdx4cv mice do not express dystrophin, the dystrophin observed in these myotubes likely originates from WT MSC nuclei, indicating reprogramming. To determine whether nuclear reprogramming also occurs in vivo, we transplanted myomaker+ MSCs into the TAs of mdx4cv mice without injury and assayed for fusion and reprogramming at 2 and 6 wk after transplantation. Myomaker+ MSCs fused to dystrophic myofibers; however, we did not observe detectable levels of dystrophin either 2 or 6 wk after transplantation (Fig. 3C). GFP+ myoblasts from WT mice were also transplanted into mdx4cv mice for use as a positive control for dystrophin restoration (Fig. 3C). Quantification of GFP+ myofibers per section revealed that myomaker+ MSCs fused to approximately 200 mdx4cv myofibers per section (Fig. 3D). We also treated mice with the histone deacetylase inhibitor TSA as a means to globally enhance transcriptional activity; however, this approach also did not result in dystrophin restoration (Fig. 3C). These results indicate that myomaker+ MSCs are refractory to detectable levels of dystrophin reprogramming that would be therapeutically relevant.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of dystrophin restoration in mdx4cv muscle after heterologous fusion. A) Schematic of protocol for in vitro fusion study. GFP+ myomaker+ MSCs were cocultured with primary myoblasts isolated from mdx4cv mice and differentiated. B) Cells were fixed after 5 d of differentiation and immunostained with a dystrophin antibody. Dystrophin expression was observed at membrane of myotubes fused with myomaker+ MSCs but not in unfused mdx4cv myotubes. C) Muscle sections 2 or 6 wk after transplantation of GFP-expressing myomaker+ MSCs, or WT-GFP myoblasts as control, into uninjured TA muscles of mdx4cv mice. One group of mdx4cv mice was treated with TSA to enhance reprogramming. Fusion (GFP+ myofibers) was observed at both time points, but GFP+ dystrophin+ myofibers were detected only in myoblast-transplanted muscle. Dystrophin+ myofibers in myomaker+ MSC transplanted muscle are not GFP+ and are likely revertants (arrowheads). D) Quantification of number of GFP+ fibers per section in muscles 2 wk after MSC transplantation; n = 4 muscles. *P < 0.05 compared to empty. Scale bars, 25 µm (B); 100 µm (C). Data are presented as means ± sem.

Fusion and nuclear reprogramming of myomaker-CBSCs and myomaker-TTFs

We sought to determine whether myomaker-mediated heterologous fusion and lack of functional reprogramming were restricted to MSCs or whether a similar phenomenon occurred in other heterologous cells. We tested TTFs because they have exhibited reprogramming in classic heterokaryon experiments and CBSCs because they are similar to MSCs, although they may be in a more primitive state (30). We mixed either GFP+ myomaker+ TTFs or mTom+ myomaker+ CBSCs with mdx4cv myoblasts (Fig. 4A), and successfully detected fusion and dystrophin reprogramming in vitro (Fig. 4B). Myomaker levels in MSCs, CBSCs, and TTFs were comparable (Fig. 4C). Both cell types were then transplanted into TAs of mdx4cv mice without injury, and fusion was observed (Fig. 4D). Myomaker+ TTFs and myomaker+ CBSCs fused at similar levels to mdx4cv muscle compared to myomaker+ MSCs (Fig. 4E). Similar to what was observed with myomaker+ MSCs, we did not detect dystrophin restoration in mdx4cv muscle after fusion with either myomaker+ TTFs or myomaker+ CBSCs (Fig. 4D). Dystrophin was also not detected 7 wk after transplantation of CBSCs (data not shown). These data, taken together, suggest that myomaker enhances fusion of multiple non–muscle cell types with muscle but that dystrophin protein is not restored.

Figure 4.

Myomaker-mediated heterologous fusion of CBSCs and TTFs with mdx4cv muscle and dystrophin reprogramming. A) Schematic of protocol for in vitro fusion study. CBSCs were isolated from tibias and femurs of Rosa26mTmG mice and infected with myomaker retrovirus. TTFs were isolated from tail tips of WT mice and retrovirally transduced with myomaker and GFP. Cells were cocultured with mdx4cv primary myoblasts and differentiated. B) Cocultured cells were fixed after 5 d of differentiation and immunostained with myosin and dystrophin (DMD) antibodies. Myomaker+ CBSCs and TTFs fused with myoblasts and formed chimeric myotubes, which displayed dystrophin expression at membrane. C) Real-time quantitative PCR for myomaker in MSCs, CBSCs, and TTFs demonstrates that myomaker expression is similar after infection of nonmuscle cells. Each cell type exhibits higher myomaker levels than differentiated myoblasts (DM). GM, growth medium. D) Representative muscle sections 2 and 10 wk after transplantation of CBSCs and TTFs, respectively, into uninjured TA muscles of mdx4cv mice. mTom+ or GFP+ myofibers were observed in myomaker-cell-transplanted muscles, indicating fusion; however, dystrophin was not detected in them. Only revertant fibers (arrowheads) were observed in mdx4cv mice. E) Quantification of number of mTom+ or GFP+ fibers per section; n = 3 or 4 muscles. *P < 0.05 compared to empty. Data are presented as means ± sem. Scale bars, 100 µm (B, first and third panels; D); 25 µm (B, second and fourth panels).

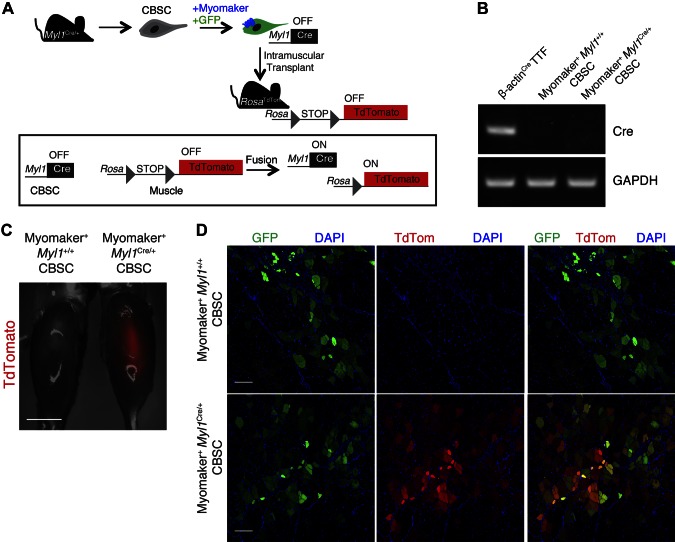

Nondystrophin nuclear reprogramming in vivo after heterologous fusion

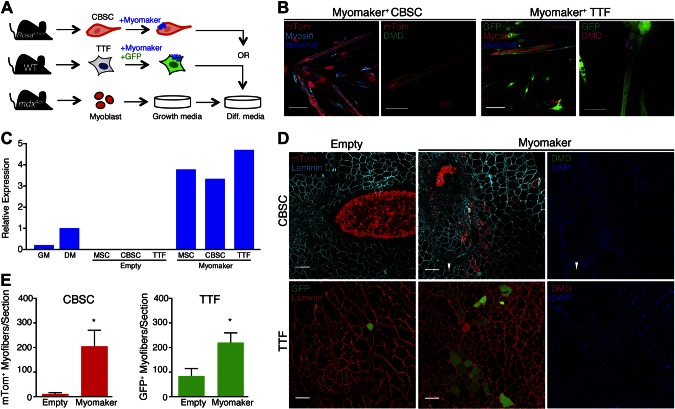

Given our data that heterologous fusion does not induce functional dystrophin reprogramming, we asked whether reprogramming occurs using a dystrophin-independent system. We isolated CBSCs from Myl1Cre/+ mice, which express Cre under control of the skeletal muscle-specific myosin, light polypeptide 1 (Myl1 or MLC1f) locus (36). Myl1Cre/+ CBSCs were infected with myomaker and GFP retroviruses, then transplanted into CTX-injured TAs of Rosa26tdTomato mice, which harbor a Cre-dependent tdTomato cassette (Fig. 5A). Thus, for reprogramming in this system, the factors necessary for Myl1 expression would have to diffuse into the CBSC nuclei because these nuclei do not normally express Myl1. This would activate Cre in CBSC nuclei; then Cre would need to migrate into the endogenous Rosa26tdTomato myonuclei to induce tdTomato expression (Fig. 5A). We first made certain that GFP+ myomaker+ Myl1Cre/+ CBSCs did not express Cre before transplantation. Indeed, RT-PCR for Cre was not detected in Myl1Cre/+ CBSCs but was clearly detected in cells that express a ubiquitous β-actin-Cre construct, which served as a positive control for Cre PCR (Fig. 5B). Whole-mount fluorescence imaging of TA muscles of Rosa26tdTomato mice revealed that transplantation of myomaker+ Myl1Cre/+ CBSCs, but not myomaker+ Myl1+/+ CBSCs, induced tdTomato expression (Fig. 5C). Cryosectioning also demonstrated that while myomaker+ Myl1+/+ CBSCs fused to muscle (GFP+ myofibers), tdTomato expression was not observed (Fig. 5D). In contrast, after fusion of myomaker+ Myl1Cre/+ CBSCs, colocalization of GFP and tdTomato was detected, indicating efficient reprogramming (Fig. 5D). Overall, these findings suggest that muscle-dependent reprogramming occurs in vivo but could be dependent on the locus of a particular gene, and that dystrophin may be a difficult gene to activate through reprogramming-dependent approaches.

Figure 5.

Nondystrophin in vivo reprogramming induced by heterologous cell fusion. A) Schematic of protocol for detection of in vivo reprogramming. CBSCs were isolated from Myl1Cre/+ mice, transduced with myomaker and GFP retroviruses, and transplanted into CTX-injured TAs of Rosa26tdTomato mice. B) PCR for Cre demonstrates that myomaker+ Myl1Cre/+ CBSCs do not express Cre. TTFs from β-actin-Cre mice were used as positive control. C) Whole-mount fluorescence image of Rosa26tdTomato muscles transplanted with either myomaker+ Myl1+/+ CBSCs or myomaker+ Myl1Cre/+ CBSCs 4 wk after transplantation. D) Representative sections of TAs from Rosa26tdTomato mice after transplantation. Both myomaker+ Myl1+/+ CBSCs and myomaker+ Myl1Cre/+ CBSCs fused (GFP+ myofibers); however, tdTomato expression (reprogramming) was only observed in muscles transplanted with myomaker+ Myl1Cre/+ CBSCs. Scale bars, 1 cm (C); 100 µm (D).

DISCUSSION

We examined fusion of various nonmuscle cells with muscle and subsequent nuclear reprogramming. Because a molecule that specifically controls muscle cell fusion was only recently uncovered, a major goal of this work was to evaluate the efficiency of heterologous fusion to restore dystrophin expression in mdx4cv mice as proof of concept for using this strategy as a gene delivery vehicle. We used the muscle-specific fusion factor myomaker to enhance fusion of MSCs, CBSCs, and TTFs with skeletal muscle. Although each of the cell types was able to fuse to muscle after myomaker expression, dystrophin restoration was detected in a subset of cultured myotubes but not in myofibers of mdx4cv mice. However, adult myofibers are able to undergo reprogramming, as myomaker+ CBSCs that express Cre from the muscle-specific Myl1 locus were able to activate Cre-dependent tdTomato expression in myofiber nuclei after fusion.

Effective therapy for genetic muscle diseases, such as MD, requires delivery of therapeutic material throughout the body’s musculature. Introduction of a functional copy of dystrophin into skeletal muscle of a DMD patient could theoretically be accomplished by viral or nonviral methods. Currently the preeminent candidate for virus-mediated gene delivery is adeno-associated virus, which can transduce both cardiac and skeletal muscle via systemic delivery (37). However, adeno-associated viruses (and other viral constructs) exhibit a limited packaging capacity, requiring delivery of a smaller, less functional μ-dystrophin or Cas9 to repair endogenous mutations (4–6, 8). Strategies that could be used alone or in conjunction with viral gene delivery include cell-based therapies, an approach that delivers normal cells to dystrophic tissue, thereby providing nuclei that encode a functional copy of the mutated gene (38). Many cell types have been explored for their potential to contribute to skeletal muscle and rescue dystrophin expression in DMD; however, the source of cells remains a major issue. For example, myoblasts are difficult to isolate and expand, and they have not been efficacious in clinical trials (39, 40). Many investigators are pioneering efforts to generate muscle stem cells using induced pluripotent stem-cell technology (9, 12, 13), which could increase the pool of cells available for transplantation; however, induced pluripotent stem-cell induction and subsequent differentiation can be a cumbersome methodology. The present technology using myomaker-transduced nonmuscle cells may provide a simpler platform that also overcomes the issue of obtaining sufficient quantities of donor cells.

Cell–cell fusion is necessary for fertilization and the development of skeletal muscle, placental trophoblasts, and osteoclasts, and it can also occur between bone marrow–derived cells (BMDCs) and peripheral tissues, such as skeletal muscle, heart, liver, and neurons, albeit at low frequencies (21, 23, 41–43). Naturally occurring fusion of BMDCs increases during injury and inflammation; however, it is not understood whether BMDC fusion during inflammation is specifically regulated or whether it occurs in a stochastic manner as a result of cellular interactions that may occur during tissue remodeling after injury. The latter possibility could explain why nonmuscle cells exhibit a low level of fusion with muscle even without the expression of myomaker. An alternative explanation is that BMDCs express other proteins required for fusion. In support of this concept, myomaker KO myoblasts exhibit more fusogenic ability compared to BMDCs, potentially because they exhibit greater expression of the other proteins required for fusion. We anticipate that further elucidation of myoblast fusion mechanisms may aid in the design of an ideal fusion-based cell therapy.

We demonstrated that MSCs and CBSCs can be suitable vehicles for myomaker-based gene delivery. MSCs exhibit the most clinically relevant characteristics for their use in cell therapy because they are readily available from bone marrow or adipose tissue, and they can be easily expanded and propagated in the absence of genomic instabilities. Moreover, MSCs could be used in allogeneic settings because they express minimal major histocompatibility complex class I and II, and they exhibit immunomodulatory properties that would be an added benefit to their use in myomaker-based heterologous fusion (27, 44). Although CBSCs are less characterized than MSCs and have not yet been evaluated in clinical studies, they show beneficial effects on cardiac injury by secretion of trophic factors after engraftment in mice (30). If dystrophin could be reexpressed using reprogramming-independent approaches, the fusion efficiency of myomaker+ MSCs, CBSCs, and/or TTFs may need to be enhanced to elicit a functional recovery. In the current study, 5% of myofibers in an uninjured mdx4cv muscle fused with myomaker-expressing nonmuscle cells after a single transplantation. If all of these fibers expressed dystrophin at physiologic levels, it is debatable whether there would be an associated functional improvement. Many studies indicate that 10 to 20% of dystrophin+ fibers are required for recovery of force production, although other results suggest a functional improvement could be reached with fewer dystrophin-expressing fibers if dystrophin was homogenously along the membrane (45, 46). A major obstacle of cell therapy for skeletal muscle is that the majority of cells exhibit little to no ability to circulate, cross the blood–tissue barrier, or even migrate from the site of injection after an intramuscular dose. While intraarterial delivery of these nonmigratory cells is a potential alternative way to target larger muscle groups than what can be achieved with intramuscular injections, another approach would be to engineer a naturally circulating cell to robustly fuse with muscle.

Reprogramming of a differentiated cell can be accomplished through expression of transcription factors or by cell fusion. Indeed, expression of MyoD in fibroblasts is sufficient for conversion to muscle, and ectopic expression of defined factors into somatic cells induces transformation to pluripotency (47, 48). In cell culture, heterokaryon formation between muscle cells and fibroblasts or hepatocytes results in activation of muscle genes from the nonmuscle nuclei (18). While cell fusion–induced reprogramming has been studied in vitro, few studies have assessed this phenomenon in vivo. Mouse retinal neurons undergo reprogramming after fusion with hematopoietic progenitors during injury, which ultimately results in partial regeneration of the retina (49). Our analysis of nuclear reprogramming in vivo indicates that reprogramming is not universally activated because we did not biochemically detect dystrophin expression from nonmuscle nuclei in mdx4cv mice, but we did observe activation of the Myl1 locus. This hypothesis is consistent with work correlating the lack of reprogramming of a particular gene with its genomic distance, defined as the transcriptional start site to the end of the 3′ untranslated region (50). Given that dystrophin is one of the longest genes in the genome and is likely under the control of numerous genomic regulatory elements, the requirements for activation of dystrophin transcription may be too challenging through reprogramming. Another interpretation is that Cre-dependent reprogramming was observed because it is a highly sensitive system where small amounts of Cre could activate a brightly fluorescent tdTomato protein under the control of a strong Rosa promoter. Additionally, while tdTomato rapidly diffuses throughout the myofiber, dystrophin expression could be localized to specific areas of the myofiber, which makes the detection more difficult. It is also plausible that dystrophin reprogramming requires an even greater amount of fusion than what was achieved in this study. To this end, evaluation of the number of nonmuscle nuclei contributed to mdx muscle would require technical advances that directly and indelibly label nonmuscle nuclei before fusion and do not leak into endogenous myofiber nuclei after fusion. Finally, the experiments presented here do not exclude possible effects of myomaker expression on Myl1 gene reprogramming; however, myomaker is not sufficient to convert nonmuscle cells to muscle, suggesting that myomaker does not directly influence reprogramming.

In summary, myomaker allows multiple cell types to fuse to WT and dystrophic muscle in vivo; however, reprogramming of the dystrophin gene is inefficient for therapeutic purposes. Nonetheless, myomaker-mediated fusion of nonmuscle cells could provide an opportunity to deliver therapeutic material to dystrophic myofibers through the use of reprogramming-independent strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank J. Cancelas (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center) for mouse MSCs. This work was supported, in part, by grants to D.P.M. from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation, U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01AR068286), the Muscular Dystrophy Association, and Pew Charitable Trusts.

Glossary

- bFGF

fibroblast growth factor–basic

- BMDC

bone marrow–derived cell

- CBSC

cortical bone stem cell

- CTX

cardiotoxin

- DMD

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- KO

knockout

- MD

muscular dystrophy

- MSC

mesenchymal stromal cell

- mTom

membrane Tomato

- Myl1

myosin, light polypeptide 1

- PDGF

human platelet-derived growth factor

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- TA

tibialis anterior

- TSA

trichostatin A

- TTF

tail-tip fibroblast

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D. P. Millay, R. J. Vagnozzi, and Y. Mitani designed research, performed research, and analyzed data; and D. P. Millay and Y. Mitani wrote the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Durbeej M., Campbell K. P. (2002) Muscular dystrophies involving the dystrophin–glycoprotein complex: an overview of current mouse models. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12, 349–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monaco A. P., Neve R. L., Colletti-Feener C., Bertelson C. J., Kurnit D. M., Kunkel L. M. (1986) Isolation of candidate cDNAs for portions of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene. Nature 323, 646–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimizu-Motohashi Y., Miyatake S., Komaki H., Takeda S., Aoki Y. (2016) Recent advances in innovative therapeutic approaches for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: from discovery to clinical trials. Am. J. Transl. Res. 8, 2471–2489 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long C., Amoasii L., Mireault A. A., McAnally J. R., Li H., Sanchez-Ortiz E., Bhattacharyya S., Shelton J. M., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2016) Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Science 351, 400–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabebordbar M., Zhu K., Cheng J. K., Chew W. L., Widrick J. J., Yan W. X., Maesner C., Wu E. Y., Xiao R., Ran F. A., Cong L., Zhang F., Vandenberghe L. H., Church G. M., Wagers A. J. (2016) In vivo gene editing in dystrophic mouse muscle and muscle stem cells. Science 351, 407–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson C. E., Hakim C. H., Ousterout D. G., Thakore P. I., Moreb E. A., Castellanos Rivera R. M., Madhavan S., Pan X., Ran F. A., Yan W. X., Asokan A., Zhang F., Duan D., Gersbach C. A. (2016) In vivo genome editing improves muscle function in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Science 351, 403–407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yue Y., Li Z., Harper S. Q., Davisson R. L., Chamberlain J. S., Duan D. (2003) Microdystrophin gene therapy of cardiomyopathy restores dystrophin–glycoprotein complex and improves sarcolemma integrity in the mdx mouse heart. Circulation 108, 1626–1632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gregorevic P., Blankinship M. J., Allen J. M., Chamberlain J. S. (2008) Systemic microdystrophin gene delivery improves skeletal muscle structure and function in old dystrophic mdx mice. Mol. Ther. 16, 657–664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filareto A., Parker S., Darabi R., Borges L., Iacovino M., Schaaf T., Mayerhofer T., Chamberlain J. S., Ervasti J. M., McIvor R. S., Kyba M., Perlingeiro R. C. (2013) An ex vivo gene therapy approach to treat muscular dystrophy using inducible pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Commun. 4, 1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampaolesi M., Torrente Y., Innocenzi A., Tonlorenzi R., D’Antona G., Pellegrino M. A., Barresi R., Bresolin N., De Angelis M. G., Campbell K. P., Bottinelli R., Cossu G. (2003) Cell therapy of alpha-sarcoglycan null dystrophic mice through intra-arterial delivery of mesoangioblasts. Science 301, 487–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cossu G., Previtali S. C., Napolitano S., Cicalese M. P., Tedesco F. S., Nicastro F., Noviello M., Roostalu U., Natali Sora M. G., Scarlato M., De Pellegrin M., Godi C., Giuliani S., Ciotti F., Tonlorenzi R., Lorenzetti I., Rivellini C., Benedetti S., Gatti R., Marktel S., Mazzi B., Tettamanti A., Ragazzi M., Imro M. A., Marano G., Ambrosi A., Fiori R., Sormani M. P., Bonini C., Venturini M., Politi L. S., Torrente Y., Ciceri F. (2015) Intra-arterial transplantation of HLA-matched donor mesoangioblasts in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. EMBO Mol. Med. 7, 1513–1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young C. S., Hicks M. R., Ermolova N. V., Nakano H., Jan M., Younesi S., Karumbayaram S., Kumagai-Cresse C., Wang D., Zack J. A., Kohn D. B., Nakano A., Nelson S. F., Miceli M. C., Spencer M. J., Pyle A. D. (2016) A Single CRISPR-Cas9 deletion strategy that targets the majority of DMD patients restores dystrophin function in hiPSC-derived muscle cells. Cell Stem Cell 18, 533–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quattrocelli M., Swinnen M., Giacomazzi G., Camps J., Barthélemy I., Ceccarelli G., Caluwé E., Grosemans H., Thorrez L., Pelizzo G., Muijtjens M., Verfaillie C. M., Blot S., Janssens S., Sampaolesi M. (2015) Mesodermal iPSC-derived progenitor cells functionally regenerate cardiac and skeletal muscle. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 4463–4482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muir L. A., Nguyen Q. G., Hauschka S. D., Chamberlain J. S. (2014) Engraftment potential of dermal fibroblasts following in vivo myogenic conversion in immunocompetent dystrophic skeletal muscle. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 1, 14025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dumont N. A., Bentzinger C. F., Sincennes M. C., Rudnicki M. A. (2015) Satellite cells and skeletal muscle regeneration. Compr. Physiol. 5, 1027–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millay D. P., O’Rourke J. R., Sutherland L. B., Bezprozvannaya S., Shelton J. M., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2013) Myomaker is a membrane activator of myoblast fusion and muscle formation. Nature 499, 301–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Millay D. P., Sutherland L. B., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2014) Myomaker is essential for muscle regeneration. Genes Dev. 28, 1641–1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiu C. P., Blau H. M. (1984) Reprogramming cell differentiation in the absence of DNA synthesis. Cell 37, 879–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pomerantz J. H., Mukherjee S., Palermo A. T., Blau H. M. (2009) Reprogramming to a muscle fate by fusion recapitulates differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 122, 1045–1053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Long M. A., Rossi F. M. (2011) Targeted cell fusion facilitates stable heterokaryon generation in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One 6, e26381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chretien F., Dreyfus P. A., Christov C., Caramelle P., Lagrange J. L., Chazaud B., Gherardi R. K. (2005) In vivo fusion of circulating fluorescent cells with dystrophin-deficient myofibers results in extensive sarcoplasmic fluorescence expression but limited dystrophin sarcolemmal expression. Am. J. Pathol. 166, 1741–1748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gussoni E., Soneoka Y., Strickland C. D., Buzney E. A., Khan M. K., Flint A. F., Kunkel L. M., Mulligan R. C. (1999) Dystrophin expression in the mdx mouse restored by stem cell transplantation. Nature 401, 390–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lapidos K. A., Chen Y. E., Earley J. U., Heydemann A., Huber J. M., Chien M., Ma A., McNally E. M. (2004) Transplanted hematopoietic stem cells demonstrate impaired sarcoglycan expression after engraftment into cardiac and skeletal muscle. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 1577–1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caplan A. I. (1991) Mesenchymal stem cells. J. Orthop. Res. 9, 641–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pittenger M. F., Mackay A. M., Beck S. C., Jaiswal R. K., Douglas R., Mosca J. D., Moorman M. A., Simonetti D. W., Craig S., Marshak D. R. (1999) Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 284, 143–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoogduijn M. J., Betjes M. G., Baan C. C. (2014) Mesenchymal stromal cells for organ transplantation: different sources and unique characteristics? Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 19, 41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Najar M., Raicevic G., Fayyad-Kazan H., Bron D., Toungouz M., Lagneaux L. (2016) Mesenchymal stromal cells and immunomodulation: a gathering of regulatory immune cells. Cytotherapy 18, 160–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lalu M. M., McIntyre L., Pugliese C., Fergusson D., Winston B. W., Marshall J. C., Granton J., Stewart D. J.; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group (2012) Safety of cell therapy with mesenchymal stromal cells (SafeCell): a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. PLoS One 7, e47559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu H., Guo Z. K., Jiang X. X., Li H., Wang X. Y., Yao H. Y., Zhang Y., Mao N. (2010) A protocol for isolation and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from mouse compact bone. Nat. Protoc. 5, 550–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duran J. M., Makarewich C. A., Sharp T. E., Starosta T., Zhu F., Hoffman N. E., Chiba Y., Madesh M., Berretta R. M., Kubo H., Houser S. R. (2013) Bone-derived stem cells repair the heart after myocardial infarction through transdifferentiation and paracrine signaling mechanisms. Circ. Res. 113, 539–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lepper C., Conway S. J., Fan C. M. (2009) Adult satellite cells and embryonic muscle progenitors have distinct genetic requirements. Nature 460, 627–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalez-Nieto D., Li L., Kohler A., Ghiaur G., Ishikawa E., Sengupta A., Madhu M., Arnett J. L., Santho R. A., Dunn S. K., Fishman G. I., Gutstein D. E., Civitelli R., Barrio L. C., Gunzer M., Cancelas J. A. (2012) Connexin-43 in the osteogenic BM niche regulates its cellular composition and the bidirectional traffic of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors. Blood 119, 5144–5154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Millay D. P., Gamage D. G., Quinn M. E., Min Y. L., Mitani Y., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2016) Structure–function analysis of myomaker domains required for myoblast fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2116–2121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., Tinevez J. Y., White D. J., Hartenstein V., Eliceiri K., Tomancak P., Cardona A. (2012) Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Folker E. S., Baylies M. K. (2013) Nuclear positioning in muscle development and disease. Front. Physiol. 4, 363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bothe G. W., Haspel J. A., Smith C. L., Wiener H. H., Burden S. J. (2000) Selective expression of Cre recombinase in skeletal muscle fibers. Genesis 26, 165–166 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duan D. (2016) Systemic delivery of adeno-associated viral vectors. Curr. Opin. Virol. 21, 16–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rinaldi F., Perlingeiro R. C. (2014) Stem cells for skeletal muscle regeneration: therapeutic potential and roadblocks. Transl. Res. 163, 409–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bajek A., Porowinska D., Kloskowski T., Brzoska E., Ciemerych M. A., Drewa T. (2015) Cell therapy in Duchenne muscular dystrophy treatment: clinical trials overview. Crit. Rev. Eukaryot. Gene Expr. 25, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller R. G., Sharma K. R., Pavlath G. K., Gussoni E., Mynhier M., Lanctot A. M., Greco C. M., Steinman L., Blau H. M. (1997) Myoblast implantation in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: the San Francisco study. Muscle Nerve 20, 469–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Camargo F. D., Green R., Capetanaki Y., Jackson K. A., Goodell M. A. (2003) Single hematopoietic stem cells generate skeletal muscle through myeloid intermediates. Nat. Med. 9, 1520–1527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Corbel S. Y., Lee A., Yi L., Duenas J., Brazelton T. R., Blau H. M., Rossi F. M. (2003) Contribution of hematopoietic stem cells to skeletal muscle. Nat. Med. 9, 1528–1532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johansson C. B., Youssef S., Koleckar K., Holbrook C., Doyonnas R., Corbel S. Y., Steinman L., Rossi F. M., Blau H. M. (2008) Extensive fusion of haematopoietic cells with Purkinje neurons in response to chronic inflammation. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 575–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel S. A., Sherman L., Munoz J., Rameshwar P. (2008) Immunological properties of mesenchymal stem cells and clinical implications. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz.) 56, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li D., Yue Y., Duan D. (2010) Marginal level dystrophin expression improves clinical outcome in a strain of dystrophin/utrophin double knockout mice. PLoS One 5, e15286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Godfrey C., Muses S., McClorey G., Wells K. E., Coursindel T., Terry R. L., Betts C., Hammond S., O’Donovan L., Hildyard J., El Andaloussi S., Gait M. J., Wood M. J., Wells D. J. (2015) How much dystrophin is enough: the physiological consequences of different levels of dystrophin in the mdx mouse. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 4225–4237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lassar A. B., Paterson B. M., Weintraub H. (1986) Transfection of a DNA locus that mediates the conversion of 10T1/2 fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell 47, 649–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takahashi K., Yamanaka S. (2006) Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell 126, 663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanges D., Romo N., Simonte G., Di Vicino U., Tahoces A. D., Fernández E., Cosma M. P. (2013) Wnt/β-catenin signaling triggers neuron reprogramming and regeneration in the mouse retina. Cell Reports 4, 271–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Looney T. J., Zhang L., Chen C. H., Lee J. H., Chari S., Mao F. F., Pelizzola M., Zhang L., Lister R., Baker S. W., Fernandes C. J., Gaetz J., Foshay K. M., Clift K. L., Zhang Z., Li W. Q., Vallender E. J., Wagner U., Qin J. Y., Michelini K. J., Bugarija B., Park D., Aryee E., Stricker T., Zhou J., White K. P., Ren B., Schroth G. P., Ecker J. R., Xiang A. P., Lahn B. T. (2014) Systematic mapping of occluded genes by cell fusion reveals prevalence and stability of cis-mediated silencing in somatic cells. Genome Res. 24, 267–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]