Abstract

Background

The extant literature demonstrates that children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) often have difficulty interacting and socially connecting with typically developing classmates. However, some children with ASD have social outcomes that are consistent with their typically developing counterparts. Little is known about this subgroup of children with ASD. This study examined the stable (unlikely to change) and malleable (changeable) characteristics of socially successful children with ASD.

Methods

This study used baseline data from three intervention studies performed in public schools in the Southwestern United States. A total of 148 elementary-aged children with ASD in 130 classrooms in 47 public schools participated. Measures of playground peer engagement and social network salience (inclusion in informal peer groups) were obtained.

Results

The results demonstrated that a number of malleable factors significantly predicted playground peer engagement (class size, autism symptom severity, peer connections) and social network salience (autism symptom severity, peer connections, received friendships). In addition, age was the only stable factor that significantly predicted social network salience. Interestingly, two malleable (i.e., peer connections and received friendships) and no stable factors (i.e., age, IQ, sex) predicted overall social success (e.g., high playground peer engagement and social network salience) in children with ASD.

Conclusions

School-based interventions should address malleable factors such as the number of peer connections and received friendships that predict the best social outcomes for children with ASD.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, individual characteristics, school, social skills

Introduction

Social impairment is a significant challenge that affects children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Many studies of elementary school-aged children with ASD have focused on the deficits of children with ASD in comparing outcomes to children without ASD. These studies have identified several areas where children with ASD have consistently demonstrated poorer outcomes in comparison to typically developing peers (Bauminger et al., 2008a; Kasari, Locke, Gulsrud, & Rotheram-Fuller, 2011). It has been well documented that school-aged children with ASD often are: 1) unengaged and isolated on the playground (Frankel, Gorospe, Chang, & Sugar, 2011; Macintosh & Dissayanake, 2006; Corbett et al., 2014); 2) more peripherally included in peer social networks (Rotheram-Fuller, Chamberlain, Kasari, & Locke, 2010); 3) less likely to have reciprocal friendships (Bauminger, Solomon, & Rogers, 2010); 4) more likely to have poorer quality relationships (Calder, Hill, & Pellicano, 2012); and 5) more likely to be rejected as compared to their typically developing peers (Locke, Kasari, Rotheram-Fuller, Kretzmann, & Jacobs, 2013). While these studies have identified discrepancies in critical areas of social development, they do not highlight the strengths and abilities of children with ASD. There are a number of children with ASD who despite their diagnosis, are socially successful with peers in school settings with little to no intervention supports. Yet, to date, relatively little is known about this subgroup of children with ASD.

Children with ASD often face complex social challenges in school, particularly in inclusive settings. The inclusion of children with ASD in general education classrooms increases exposure and opportunities to interact with typically developing peers and allows the opportunity to examine meaningful social outcomes such as peer engagement and social network salience, or connectedness with peers (Boutot & Bryant, 2005). Studies of included children with ASD have generally focused on children who do not have a comorbid intellectual disability (IQ>70). These studies have found similarities in friendship development (Bauminger, Solomon, & Rogers, 2010), initiation and response rates, and comparable playground engagement with peers (Locke, Shih, Kretzmann, & Kasari, 2015).

There is a common misconception that all children with ASD experience negative social outcomes and require intense intervention supports in schools. While this may be true for many children with ASD, there are others who are well liked and socially connected. While researchers are learning more about friendship in children with ASD, there is still very little known about what characterizes friendship and social engagement in these children (Bauminger et al., 2008b). Although there is some evidence that children with ASD do indeed have meaningful and reciprocal friendships (Kasari et al., 2011; Bauminger et al., 2008a; Bauminger et al., 2008b), it is unclear how many children with ASD are socially well-adjusted and successful with peers on the playground and/or in the classroom as well as what characterizes this subgroup of children. The purpose of this paper was to examine the characteristics of socially successful children with ASD. Understanding the characteristics of this subgroup of children with ASD and the specific factors that predict social success may point to the ways in which schools address these outcomes and support other children with ASD with greater social needs. We hypothesize that there will be both malleable (i.e., friendship characteristics, class size, autism symptom severity) and stable factors (e.g., IQ, sex, age) that characterize this subgroup of children.

Method

Participants

Study participants were drawn from three large school-based randomized controlled intervention studies. Only participants at UCLA were included in these analyses. Study 1 was a randomized controlled-field trial of 60 students that examined a peer-mediated intervention as compared to an adult-mediated intervention for children with ASD (see Kasari et al., 2012). Study 2 was a randomized controlled-field trial of 51 students that examined a peer-mediated social engagement group for children with ASD as compared to a social skills group for children with general social challenges (see Kasari et al. 2016), and Study 3 was a randomized controlled-field trial of 37 students that examined an adult-facilitated intervention for children with ASD as compared to a waitlist control treatment as usual condition (see AIR-B network, 2012–2015). A total of 148 elementary-aged children with ASD in 130 classrooms in 47 public schools participated. All studies included children who were referred by school administrators and had a diagnosis of ASD from a licensed professional, had a documented nonverbal IQ of 64 or higher, and were included in a general education K-5 classroom for at least 51% of the school day (mean time in inclusion for this sample was 82%). The remaining time of the school day was spent in self-contained settings, speech, physical, and occupational therapy, and or a learning support environment (e.g., resource room). Only baseline data (i.e., prior to receipt of intervention) from the three studies were used. The sample was predominantly male (89.2%) with an average age of 8.37, SD=1.66 years and an average IQ of 91.16 (SD=15.11). Four children were in Kindergarten, 26 children were in first grade, 36 children were in second grade, 26 children were in third grade, 27 children were in fourth grade, and 29 children were in fifth grade. The ethnic backgrounds of the children were as follows: 30.7% Caucasian, 9.8% African American, 25.2 % Asian, 25.2% Latino and 9.1% Other. See Table 1 for demographic information.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, engagement, and social network salience for children with ASD

| Demographics | Baseline Characteristics (n=148) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mean (SD) | Range | |

|

|

||

| Age | 8.37 (1.66) | (5, 12) |

| Class Size | 29.4 (11.56) | (14, 81) |

| ADOS Severity | 7.78 (1.90) | (1, 10) |

| IQ | 91.16 (15.11) | (64, 150) |

| POPE at Entry | ||

| Joint Engagement | 43.56 (29.77) | (0, 100) |

| Solitary | 20.18 (26.75) | (0, 100) |

| Social Network at Entry | ||

| Out-degrees | 3.56 (2.58) | (0, 15) |

| In-degrees | 1.52 (1.55) | (0, 7) |

| Social Network Salience | 0.32 (0.24) | (0, 1) |

Materials and procedure

Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS; Lord et al., 2000)

The ADOS is a clinician administered observational measure of social and communication skills used to classify children with ASD. ADOS symptom severity scores were calculated for each administration using the ADOS symptom severity algorithm (Gotham et al., 2009). Symptom severity is based on social communication impairment and restricted repetitive patterns of behavior (Gotham et al., 2009). All children with ASD were given the ADOS Module 3 to confirm an autism diagnosis for research eligibility. Data for this study were gathered prior to the release of the ADOS-2.

Cognitive assessments

Three cognitive assessments were used. Standard scores (M = 100, SD 15), from each assessment were used in the analyses.

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, fourth edition (WISC-IV; Wechsler, 2003)

The WISC-IV is a standardized intelligence test for children between the ages of 6 years to 16 years 11 months. The WISC-IV reliability coefficient for the Full Scale IQ score is 0.97. Children with ASD from Study 1 were administered the WISC-IV to confirm research eligibility. Data for this study were gathered prior to the release of the WISC-V.

Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale, fifth edition (SB-5; Roid, 2003)

The SB-5 is a standardized assessment that measures intelligence and cognitive abilities in children and adults (age 2 and 85+). IQ scores were determined from two subtests, yielding a nonverbal and verbal IQ score. The SB-5 is highly reliable, with internal consistency scores ranging from 0.95 to 0.98 across all age groups. Children with ASD from Study 2 were administered the SB-5 to confirm research eligibility.

Differential Ability Scales, second edition (DAS-II; Elliott, 2007)

The DAS-II assesses cognitive abilities in children ages 2 years 6 months through 17 years 11 months across a broad range of developmental levels. The DAS-II yields a General Conceptual Abilities score (M = 100, SD 15) that is highly reliable, with internal consistency scores ranging from 0.89 to 0.95 and a test-retest coefficient of 0.90. Children with ASD from Study 3 were administered the DAS-II to confirm research eligibility.

Playground Observation of Peer Engagement (POPE; Kasari, Rotheram-Fuller, & Locke, 2005)

The POPE is a timed-interval behavior coding system that captures playground peer engagement. Solitary (i.e., unengaged with others) and joint engagement (i.e., structured games with rules, conversations or other reciprocal activities) were measured as a percentage of intervals within the recess period. Independent observers blinded to randomization rated children with ASD on the playground for 40 consecutive seconds and then coded for 20 seconds during the recess or lunch play period (an average of 15 minutes per observation) before implementation of intervention activities occurred in each study. Independent observers were trained and considered reliable with a criterion >0.8; average κ reliability in the studies ranged from 0.79 to 0.92 across studies.

Friendship survey

Children were asked to identify classmates whom they like to hang out with (friendships) and do not like to hang out with (rejections). This free recall list of friends determined children’s number of outward and received friendship nominations and rejections. In addition, sociometric nominations from children were gathered within each participating classroom to gain a robust picture of children’s peer groups (Cairns, Cairns, Neckerman, Gest, & Gariepy, 1988). Participating students were asked: ‘Are there kids in your class who like to hang out together? Who are they?’ as a method of identifying specific children within each classroom social network grouping. Children listed the names of all children within their classroom who hung out together in a group using free call without additional prompting, class lists, or pictures. Children were reminded to include themselves in groups as well as students of both sexes. Young children (in Kindergarten and first grade) with reading and writing difficulties were interviewed individually. Only children in general education settings were asked to complete this survey.

Coding outward and received friendship nominations, rejections, and peer connections

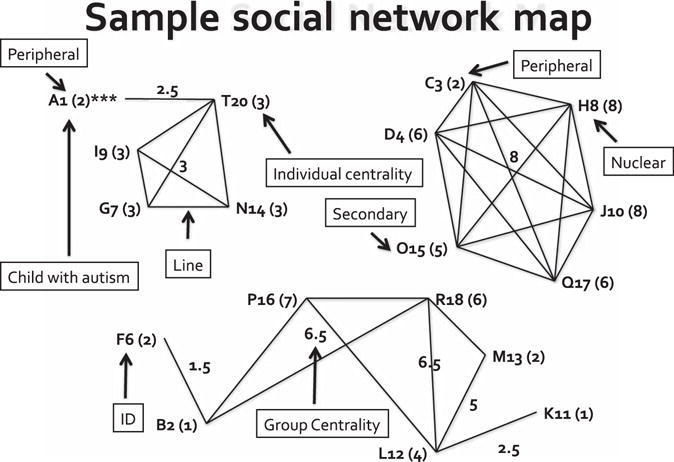

The number of outward and received friendship nominations from peers was tallied and totaled based on participating children’s responses on the Friendship Survey within each classroom. Rejections were coded as the total number of instances where children were identified as someone other children ‘did not like to hang out with.’ Lastly, peer connections were coded as the total number of peers that were significantly linked to a child on the social network map. See Figure 1. It is important to note that these data are not dependent on coding or scoring social network centrality. For example, the number of peer connections or received peer nominations is not related to social network centrality in that it is possible for children to have any number of peer connections or friendship nominations but be considered peripheral, secondary, or nuclear.

Figure 1.

Sample social network map. Each line denotes a connection. The number in parentheses next to the ID is the frequency with which that child was nominated to a social group (individual centrality). The number within the social network webs represents the child’s group centrality. Each ID (e.g., A1, B2, C3, etc.) represents a child in this classroom. A1 is the child with ASD. A1 is peripheral with 1 connection to Child T20. C3 also is peripheral, yet C3 has 5 connections to peers (D4, H8, J10, O15, and Q17) in his classroom. O15 is secondary, within the middle 40% of the classroom’s social structure. H8 is nuclear, within the top 30% of the classroom’s social structure. H8 and J10 were the most frequently listed children in the classroom with 8 total nominations to a social group.

Coding social network salience (Cairns & Cairns, 1994)

Social network salience refers to the prominence of each individual in the overall classroom social structure. Three related scores were calculated in order to determine social network salience: the child’s ‘individual centrality’ (i.e., individual popularity); the group’s ‘cluster centrality’ (i.e., popularity of the peer group); and the child’s ‘social network centrality’ (i.e., salience in the classroom). Using methods developed by Cairns and Cairns (1994), the first two types of centrality are used to determine the third (Farmer & Farmer, 1996). Based on categorizations by Farmer and Farmer (1996), four levels of social network centrality are possible (i.e., isolated, peripheral, secondary, and nuclear) to provide a system for describing how well children were integrated into their informal peer networks. Children who did not receive peer nominations to a group were considered isolated. Children in the bottom 30% of the classroom were considered peripheral. Children in the middle 40% of the classroom were considered secondary, and children in the top 30% of the classroom were considered nuclear. These categorizations were used to select children in this study.

Traditional social network classifications (Cairns & Cairns, 1994) were designed to be cross-sectional measures of children’s classroom social network salience at one time point. Children’s social network salience scores were normalized on the most nominated subject in the classroom during baseline and were calculated using children’s individual centrality divided by the highest individual centrality score within their classroom to provide a continuous metric of children’s social network salience. Social network salience scores were used as the dependent variable in the model.

Procedure

The university Institutional Review Board as well as each school district approved the study. In all studies, once families of children with ASD completed the informed consent process and met criteria for inclusion in the randomized controlled treatment trials, research personnel contacted each school and obtained a letter of agreement to participate in the study. Subsequently, research personnel distributed consent forms to all children in the target child’s classroom for participation in completion of the Friendship Survey before each intervention. Data were collected throughout one school year, and the time of year in which data collection took place depended on enrollment in the study. Only baseline data were used in this study.

Defining socially successful children

Socially successful children with ASD were identified using measures of playground engagement and social network salience. Specifically, we used the cut points described in Locke et al (2015) to identify children with ASD who were highly engaged (i.e., children with ASD who were at least jointly engaged 58% or more of the recess period). In addition, we included children with ASD who were considered highly connected (i.e., either secondary or nuclear) in their general education classroom’s social network. Consistent with social network studies in typical development, connections were examined for children in their homeroom, or main classroom. For children who also receive other services, this approach does restrict friendships to only children in their inclusion classroom. We then created three groups that were used in the following analyses. Group 1 included children with ASD who were both highly connected based on their social network salience and highly engaged on the playground (n = 24). Group 2 included children with ASD who were highly connected in their social network salience or highly engaged on the playground, but not both (n = 57). Finally, Group 3 included children with ASD who were neither highly connected in their social network salience nor highly engaged on the playground (n = 62). All students were cross-classified into one of these three groups, except for five children who were missing either playground engagement or social network salience measures at baseline.

Using these definitions, we estimated the percent of children with ASD who demonstrated high playground joint engagement and high connectivity without ongoing intervention. Overall, 32.2% of children with ASD had high initial playground engagement, 42.7% of children with ASD were highly connected in their social network salience, and 16.8% of children with ASD were highly engaged on the playground and highly connected in their social network salience.

Statistical analysis

All enrolled children were included regardless of intervention study, since no treatment was administered at baseline. Potential predictor variables were selected a priori and included the following: IQ, age, sex, autism symptom severity, class size, received friendship nominations, outward friendship nominations, rejections, and peer connections. These variables were selected a priori because they are commonly examined in school-based intervention studies of children with ASD (Kasari et al., 2012; Mandell et al., 2013; Kasari et al., 2015). Linear regression models were individually conducted for all a priori predictor variables, controlling for study, in order to capture the effect of each variable on the outcome of interest (i.e., playground joint engagement and social network salience). Subsequently, all predictors that were suggestive (p<0.10) in the univariate models adjusted for study were included in a full multiple linear regression model. To check for multicollinearity, generalized variance inflation factors were calculated for models with multiple predictors. All generalized variance inflation factors (GVIF) for the final models were less than 10, which suggests there was low multicollinearity between predictor variables. Significance of predictors in the multiple linear regression models were calculated using ANOVA type ‘III’ test statistics, and effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s f2 for local effect sizes. Effect sizes were calculated only for significant predictors in the final multiple linear regression model.

Using the group definitions for socially successful children (Group 1, Group 2, and Group 3), a multinomial logistic regression model was used to examine the effect of malleable and stable factors on social success. This regression was performed using R version 3.2.0 (http://cran.r-project.org/) and the ‘nnet’ package (Venables & Ripley 2002). Univariate multinomial logistic regressions for each predictor variable, controlling for study, were used to identify significant predictors. Odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for each of the predictor variables and significance for the final models was assessed at the α = 0.05 level. Significance of covariates was calculated using likelihood ratio χ2 test statistics and point estimates for odds ratios are interpreted as unstandardized effect sizes.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Table 1 presents demographic information as well as summary statistics for the predictor and outcome variables. The main effect of study was not significant for all outcome variables; however, all models controlled for study effect so that the difference in time of study completion would not affect the predictors.

Playground joint engagement

Class size (F(1, 118)=3.97, p=0.05, f2=0.03) and peer connections (F(1, 118)=10.44, p< 0.01, f2=0.08) showed positive associations with playground joint engagement after adjusting for study effects, while autism symptom severity (F(1, 118)=4.09, p=0.05, f2=0.05) was negatively associated [See Table 1]. On average, as class size increased, the percentage of time in joint engagement on the playground increased as well. Similarly, students with more peer connections tended to spend a greater amount of time in joint engagement. Students with higher autism symptom severity were associated with less playground engagement. Other predictors such as age (F(1,141)=0.83, p=0.36), IQ (F(1, 140)=0.73, p=0.39), sex (F(1, 141)=1.03, p=0.31), number of received friendship nominations (F(1, 139)=2.61, p=0.11), number of outward friendship nominations (F(1, 139)=2.13, p=0.15), and number of rejections (F(1, 136)=2.93, p=0.09) were not significantly associated with playground joint engagement. The number of rejections was initially included in the multiple regression model since it was suggestive (p<0.10), but it was not significant (F(1,116)=0.23, p=0.63) in the multiple regression model and therefore was excluded from the final model.

Social network salience

Age (F(1, 120)=11.56, p<0.01, f2=0.09), the number of received friendship nominations (F(1, 120)=62.22, p<0.01, f2=0.34), autism symptom severity (F(1,120)=7.07, p=0.01, f2=0.03), and peer connections (F(1, 120)=8.50, p<0.01, f2=0.07) were significant predictors of social network salience. See Table 3. Age and autism symptom severity were negatively associated with social network salience such that older children and children with higher autism symptom severity, holding all other variables constant, were more likely to have lower social network salience. On the other hand, received friendship nominations and peer connections showed positive associations with social network salience. Non-significant predictors of social network salience included: class size (p=0.20), sex (p=0.25), IQ (p=0.84), number of rejections (p=0.64), and number of outward friendship nominations (p=0.02). The number of outward friendships was tested in the multiple linear model, but it was non-significant (p=0.75) and was therefore not included in the final model.

Table 3.

Linear regression model of baseline characteristics predicting social network salience (n=127a)

| Coefficient | Estimate | SE | t value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.61 | 0.12 | 5.24 | <0.01 |

| Age | −0.03 | 0.01 | −3.40 | <0.01 |

| ADOS Severityb | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.66 | 0.01 |

| Received Friendship Nominations | 0.09 | 0.01 | 7.89 | <0.01 |

| Peer Connections | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.92 | <0.01 |

| Study 2 vs. Study 1 | −0.06 | 0.04 | −1.32 | 0.19 |

| Study 3 vs. Study 1 | <0.01 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.94 |

Two participants were missing baseline social network salience measure

19 children were missing ADOS severity measurements at baseline and were not included

Age was further examined to determine if there was a specific cut point when social network salience declines. Social network salience begins to decrease at the age of eight years old (p<0.01) for children with ASD. Children between the ages of 5–8 showed no significant association between age and social network salience, whereas children older than eight had a significant negative association.

Overall social success

When children were grouped as both highly connected based on their social network salience and highly engaged on the playground (Group 1), highly connected in their social network salience or highly engaged on the playground (Group 2) or neither highly connected in their social network salience nor highly engaged on the playground (Group 3), many of the significant predictors found in the linear regression models were no longer significant. Comparisons between groups were conducted as follows: Group 1 vs. Group 3, Group 2 vs. Group 3, and Group 1 vs. Group 2. The number of received friendship nominations was significant in the comparison of all groups (χ2)=22.52, p<0.01) such that Group 1 vs. Group 3 (OR=1.49, 95% CI (1.09, 2.04)), Group 2 vs. Group 3 (OR=2.37, CI(1.59,3.52)) and Group 1 vs. Group 2 (OR=1.59, 95% CI (1.15, 2.19)). The number of peer connections also was significant in the comparison of all groups (χ2)=9.99, p=0.01) such that Group 1 vs. Group 3 (OR=1.21, 95% CI (1.02, 1.44)) and Group 2 vs. Group 3 (OR=1.38, 95% CI(1.11, 1.71)). The 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio for the number of received friendship nominations in Group 1 vs. Group 3 was (1.09, 2.04), which suggests that students who received more friendship nominations were between 1.09 to 2.04 times more likely to have higher scores on both social network salience and playground joint engagement as compared to neither measurement. The 95% confidence interval for the odds ratio for the number of peer connections in Group 2 vs. Group 3 was (1.11, 1.71); students with more peer connections are 1.11 to 1.71 times more likely to have higher scores on either playground engagement or social network salience versus neither measurement. We note that some of these intervals are large; yet the effect remains strong enough to indicate significance of the association. Non-significant predictors in this model included the following: age, class size, autism symptom severity, IQ, sex, number of rejections, and number of outward friendship nominations. See Table 4.

Table 4.

Multinomial logistic regression for predicting socially successful children (n=143a)

| Variable | Group 1 vs Group 3 OR (95% CI) | p-value | Group 2 vs Group 3 OR (95% CI) | p-value | Group 1 vs Group 2 OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer Connections | 1.21 (1.02, 1.44) | 0.03 | 1.38 (1.11, 1.71) | <0.01 | 1.13 (0.94, 1.36) | 0.18 |

| In-Degree | 1.49 (1.09, 2.04) | 0.01 | 2.37 (1.59, 3.52) | <0.01 | 1.59 (1.15, 2.19) | 0.01 |

| Study: | ||||||

| Study 1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | |||

| Study 2 | 0.85 (0.35, 2.04) | 0.71 | 0.56 (0.14, 2.24) | 0.41 | 0.66 (0.18, 2.39) | 0.52 |

| Study 3 | 0.59 (0.22, 1.58) | 0.29 | 1.57 (0.42, 5.83) | 0.50 | 2.68 (0.76, 9.49) | 0.13 |

Note: Group 1 = highly connected and high engagement; Group 2 = highly connected or high engagement; Group 3 = neither highly connected nor high engagement

Five children did not have both joint engagement and social network salience measurements at baseline and were not included

Discussion

This study examined the malleable and stable factors that characterize socially successful children with ASD in public school settings. Social success was examined in relation to more joint engagement with peers during unstructured school periods (recess and lunch) and greater social network salience as rated by classmates. More than half of this group of children had notable success on at least one social outcome (40% on one outcome, and 17% on both). Importantly results demonstrated several malleable but few stable factors as predictive of social success.

Malleable factors provide the key to intervention targets, those aspects of a child’s environment or behavioral repertoire that can be enhanced through interventions. For example, class size is a contextual factor that can be manipulated for social-environmental benefit. In this study, class size was important to playground engagement, with larger classes better for greater engagement. Presumably more children on the playground allows children to find others like themselves to connect to, or more activities they may find interesting in which to engage. However, class size can have variable effects on outcomes, and may be difficult to orchestrate for maximal benefit. For example, some studies find that smaller class sizes are better for academic success or for children with greater levels of impairment (Nye, Hedges, & Konstantopoulos, 2000; Loe & Feldman, 2007). Further at least one study found a complicated interaction of age and sex on class size for peer relationships with girls with ASD benefitting from larger classes at older ages and boys with ASD benefitting from smaller classrooms at younger ages (Anderson, Locke, Kretzmann, & Kasari, 2015). In this study, class size only had effects on peer engagement on the playground and was not retained as a significant factor in predicting overall social success.

Autism symptom severity and peer connections were two factors associated with success in playground engagement and social network. While we consider autism symptom severity as malleable given previous studies suggesting symptoms can be improved with interventions (Fein et al, 2013; Wood, Fujii, Renno, & Van Dyke, 2014) symptom severity was not retained in analyses predicting group membership of successful versus unsuccessful children. Using previously defined criteria for social success on playground engagement and social network salience (Kasari et al, 2011; Locke et al., 2015; Shih, Shire, Kasari, 2014), we categorized children according to whether they were socially successful on one, both, or neither measure of success. Only two factors were retained in predicting group membership of social success. These two factors were the number of received friendship nominations and peer connections. Both of these factors are malleable, and thus, sensitive to change from interventions (e.g., Kasari et al, 2012). Indeed, in a school based intervention study, Kasari et al (2012) found that children with ASD received more friendship nominations after receiving a peer-mediated intervention (adult works with the peers of the child with ASD) versus an adult-mediated intervention (adult works one on one with the child with ASD). Thus, peer mediated interventions may be critically important in helping children have greater social success at school.

A number of different types of peer interventions may be successful; including ones conducted on the playground itself involving shared activities and clubs (Koegel, Vernon, Koegel, Koegel, & Paullin, 2012; Kretzmann et al., 2015), or peer social groups, such as lunchtime social skills groups (Kasari et al.a, 2016). These types of interventions have improved peer engagement on the playground as well as social networks. Further research is indicated on determining the best composition and content of peer groups, but it may be that focusing on quality (e.g., a small number of close knit friendships) rather than the quantity of friendships will yield better social success.

While stable factors were not retained in predicting socially successful group membership, age and sex are likely important considerations in intervention choice. For example, several studies have found that children have greater difficulty with peer groups at the older elementary ages. Rotheram-Fuller et al (2010) found that children with ASD were not different from typically developing children in social network salience in Kindergarten and first grade, but the gap in social network salience widened around second or third grade and continued to widen in upper elementary school. Other studies have shown that age is a significant factor in the extent to which children with ASD engage with peers (Bauminger et al., 2008a; Schupp et al., 2013; Locke et al., 2015). Consistent with this literature, our findings suggest that social network salience begins to decrease at the critical age of eight years old for children with ASD. Children’s social impairments may become more apparent at this age causing concern about the possibility of increased challenges. Developmental insight may be one explanation for these findings as children’s impairments are more likely to arise from increasing sophistication of their peers. Peers may become less tolerant of differences and begin to recognize differences between themselves and their classmate with ASD (Rotheram-Fuller et al., 2010). These results imply that interventions and supports may need to be increased during middle childhood, where children with ASD may be the most vulnerable within peer social networks. Future research is needed to determine the timing of social interventions, early for preventative purposes, or targeted at the point of difficulty.

Somewhat surprising is that IQ and peer rejections did not predict social success. Although there is some evidence to suggest that children with ASD with higher IQs (over 85) over a wide age range (ages 4–17years, M = 9.1) have more friends than children with lower IQs (Mazurek & Kanne, 2010; Bauminger-Zviely & Agam-Ben-Artzi, 2014), in this study, we found that IQ did not significantly predict any social outcome. We note a considerable range in IQ in this study, 64 to 150. Despite this, IQ was not a significant predictor of social success. Peer rejections, a potentially malleable factor, also did not predict social success. Across studies, rejections were not particularly high, and overall they did not seem to affect peer engagement on the playground or social network salience.

Limitations

Several study limitations should be noted. First, our knowledge of children’s social behavior was limited to playground observations and peer reported social network data. Thus, we were not knowledgeable about other challenges or issues children may have been experiencing. Second, this study concerned predominantly male children with ASD, and is consistent with data on average IQ children with ASD where ratios are even more lopsided towards males. Girls are often underrepresented in studies on inclusion and should be a focus of future research. Third, these data were obtained from a large urban school district with a highly diverse population of children in the Western United States. These findings may be less generalizable to other areas of the country. Fourth, these data are restricted to children with average IQ in inclusive public school settings. Different results may be found for children in self-contained classrooms, specialized schools, or children with lower IQ. Lastly, while the Friendship Survey offers a unique perspective on social networks in classrooms, from the perspective of the children themselves, there are limitations when applied to children who may not be full time members of a classroom. Children who engage in multiple contexts may have friends outside their home classroom. While this is true of all children, it may be more often the case for children with a special education designation. Thus, children with ASD were limited to children in their inclusion classroom for identification of friends. On the playground, however, they had more options to engage with children outside their classroom. Finally, friendship quality is not captured on the Friendship survey. This too could be important to capture in future studies.

Conclusion

This study examined the malleable and stable traits of a subgroup of children with ASD who are socially well connected and engaged with peers at school. This study points to certain malleable factors that may improve the playground engagement, social network salience, and overall social success of children with ASD. These findings highlight the need to learn more about socially successful children in order to inform interventions, both about content of interventions and timing. Future longitudinal research is needed to understand the trajectory of peer relationships, and particularly friendships, across the lifespan.

Table 2.

Linear regression model of baseline characteristics predicting POPE joint engagement (n=124a)

| Coefficient | Estimate | SE | t value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 37.78 | 14.42 | 2.62 | 0.01 |

| Class Sizeb | 0.48 | 0.24 | 1.99 | 0.05 |

| ADOS Severityc | −2.72 | 1.35 | −2.02 | 0.05 |

| Peer Connections | 3.23 | 1.00 | 3.23 | <0.01 |

| Study 2 vs. Study 1 | 2.68 | 6.42 | 0.42 | 0.68 |

| Study 3 vs. Study 1 | 10.28 | 6.51 | 1.58 | 0.12 |

Three children did not have baseline joint engagement measurement

Two children did not have class size measurement at baseline

19 children were missing ADOS severity measurements at baseline and were not included

Key points.

This study examined characteristics of children with autism in public schools from three intervention trials for indicators of social success.

Children with autism in large classrooms, with lower autism symptom severity and more peer connections had significantly higher playground joint engagement.

Younger children, with lower autism symptom severity, and more peer connections showed significantly higher social network salience.

The number of peer connections and the number of received friendship nominations were associated with highly successful children (on both playground engagement and social network salience).

Results suggest that there are socially successful children with autism in classrooms with identifiable malleable traits that can be addressed in intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the children and schools who participated.

This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number UA3MC11055, clinical trials number NCT00095420 titled ‘Autism Intervention Research Network in Behavioral Health’ awarded to the C.K. The information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S Government. This study also was supported by NIMH K01MH100199 awarded to the J.L.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

References

- Anderson A, Locke J, Kretzmann M, Kasari C, AIR-B Network Social network analysis of children with autism spectrum disorder: Predictors of fragmentation and connectivity in elementary school classrooms. Autism. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1362361315603568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N, Solomon M, Aviezer, Heung K, Brown J, Rogers SJ. Children with autism and their friends: A multidimensional study if friendship in high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008a;36:135–150. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N, Solomon M, Aviezer, Heung K, Brown J, Rogers SJ. Friendship in high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorder: Mixed and non-mixed dyads. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008b;38:1211–1229. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0501-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N, Solomon M, Rogers SJ. Predicting friendship quality in autism spectrum disorders and typical development. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40:751–761. doi: 10.1007/s10803-009-0928-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger-Zviely N, Agam-Ben-Artzi G. Young friendship in HFASD and typical development: Friend versus non-friend comparisons. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44:1733–1748. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumberg SJ, Bramlett MD, Kogan MD, Schieve LA, Jones JR, Lu MC. National Health Statistics Reports. Hyattsville, MD: 2013. Changes in prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder in school-aged U.S. children: 2007 to 2011–2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutot AE, Bryant DP. Social integration of students with autism in inclusive settings. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities. 2005;40:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns R, Cairns B. Lifelines and risks: Pathways of youth in our time. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns RB, Cairns BD, Neckerman HJ, Gest SD, Gariepy JL. Social networks and aggressive behavior: Peer support or peer rejection? Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:815–823. [Google Scholar]

- Calder L, Hill V, Pellicano E. ‘Sometimes I want to play by myself’: Understanding what friendship means to children with autism in mainstream primary schools. Autism. 2012;17:286–316. doi: 10.1177/1362361312467866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Swain DM, Newsom C, Wang L, Song Y, Edgerton D. Biobehavioral profiles of arousal and social motication in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:924–934. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean M, Kasari C, Shih W, Frankel F, Whitney R, Landa R, Lord C, Orlich F, King B, Harwood R. The peer relationships of girls with ASD at school: comparison to boys and girls with and without ASD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:1218–1225. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott CD. Differential Ability Scales–Second Edition (DAS-II) San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment, Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer TW, Farmer EMZ. Social relationships of students with exceptionalities in mainstream classrooms: Social networks and homophily. Exceptional Children. 1996;62(5):431–450. [Google Scholar]

- Fein D, Barton M, Eigsti I, Kelley E, Naigles L, Schultz R, Tyson K. Optimal outcomes in individuals with a history of autism. Journal of Child Psychology an Psychiatry. 2013;54:195–205. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel FD, Gorospe CM, Chang Y, Sugar CA. Mothers’ reports of play dates and observation of school playground behavior of children having high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:571–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02318.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Dean M, Kretzmann M, Shih W, Orlich F, Whitney R, Landa R, Lord C, King B. Children with autism spectrum disorder and social skills groups at school: A randomized trial comparing intervention approach and peer composition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Locke J, Gulsrud A, Rotheram-Fuller E. Social networks and friendships at school: Comparing children with and without autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41:533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Locke J. The Development of the Playground Observation of Peer Engagement (POPE) Measure. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Los Angeles; 2005. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Locke J, Gulsrud A. Making the connection: Randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2012;53:431–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel LK, Vernon TW, Koegel RL, Koegel BL, Paullin AW. Improving social engagement and initiations between children with autism spectrum disorder and their peers in inclusive settings. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. 2012;14:220–227. doi: 10.1177/1098300712437042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke J, Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E, Kretzmann M, Jacobs J. Social network changes over the school year among elementary school-aged children with and without an autism spectrum disorder. School Mental Health. 2013;5:38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Locke J, Shih W, Kretzmann M, Kasari C. Examining playground engagement between elementary school children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1362361315599468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loe IM, Feldman HM. Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:643–654. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, Lambrecht L, et al. Rutter M. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Generic: A standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:205–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintosh K, Dissanayake C. A comparative study of the spontaneous social interactions of children with high-functioning autism and children with Asperger’s disorder. Autism. 2006;10:199–220. doi: 10.1177/1362361306062026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandell DS, Stahmer AC, Shin S, Xie M, Reisinger E, Marcus SC. The role of treatment fidelity on outcomes during a randomized field trial of an autism intervention. Autism. 2013;17:281–295. doi: 10.1177/1362361312473666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek MO, Kanne N. Friendship and internalizing symptoms among children and adolescents with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2010;40:1512–1520. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1014-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nye B, Hedges LV, Konstantopoulos S. The effects of small classes on academic achievement: The results of the Tennessee class size experiment. American Educational Research Journal. 2000;37:123–151. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2015. URL http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Roid GH. Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rotheram-Fuller E, Kasari C, Chamberlain B, Locke J. Grade related changes in the social inclusion of children with autism in general education classrooms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:1227–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02289.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp CW, Simon D, Corbett BA. Cortisol responsivity differences in children with autism spectrum disorders during free and cooperative play. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43:2405–2417. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-1790-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih W, Patterson SY, Kasari C. Developing an adaptive treatment strategy for peer-related social skills for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2014;0:1–11. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.915549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szatmari P, Bryson S, Duku E, Vaccarella L, Zwaigenbaum L, Bennett T, Boyle MH. Similar developmental trajectories in autism and Asperger syndrome: From early childhood to adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1459–1467. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied Statistics with S Fourth Edition. Springer; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – Fourth Edition: Administration and Scoring Manual. San Antonio, TX: Pearson; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Fujii C, Renno R, Van Dyke M. Impact of cognitive behavioral therapy on observed autism symptom severity during school recess: A preliminary randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44:2264–2276. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]