Abstract

Background

People with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) typically have mild to moderate intellectual deficits, compulsivity, hyperphagia, obesity, and growth hormone deficiencies. Growth hormone treatment (GHT) in PWS has well-established salutatory effects on linear growth and body composition, yet cognitive benefits of GHT, seen in other patient groups, have not been well studied in PWS.

Methods

Study 1 included 96 children and youth with PWS aged 4 to 21 years who naturalistically varied in their exposures to GHT. Controlling for socio-economic status, analyses compared cognitive and adaptive behavior test scores across age-matched treatment naïve versus growth hormone treated children. Study II assessed if age of treatment initiation or treatment duration was associated with subsequent cognition or adaptive behavior in 127, 4- to-21 year olds with PWS. Study III longitudinally examined cognitive and adaptive behavior in 168 participants who were either consistently on versus off GHT for up to 4–5 years.

Results

Compared to the treatment naïve group, children receiving growth hormone treatment had significantly higher Verbal and Composite IQs, and adaptive communication and daily living skills. Children who began treatment before 12 months of age had higher Nonverbal and Composite IQs than children who began treatment between 1 to 5 years of age. Longitudinally, the groups differed in their intercepts, but not slopes, with each group showing stable IQ and adaptive behavior scores over time.

Conclusions

Cognitive and adaptive advantages should be considered an ancillary benefit and additional justification for GHT in people with PWS. Future efforts need to target apparent socio-economic inequities in accessing GHT in the PWS population.

Keywords: Prader-Willi syndrome, growth hormone treatment, cognition, adaptive behavior

Introduction

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a neurodevelopmental disorder caused by a lack of paternally derived, imprinted information on chromosome 15q11-q13. Approximately 70% of cases are due to two types of paternal deletions in this region, with Type I deletions being 500mb larger than Type II deletions. An additional 25% of cases are due to maternal uniparental disomy (mUPD), and 5% to imprinting defects and atypical deletions (see Cassidy et al., 2012 for a review). People with PWS manifest mild to moderate intellectual disabilities, compulsivity, irritability, aggression and hyperphagia that can lead to life-threatening obesity. Some of these features vary across genetic subtypes of PWS. Those with Type I deletions, for example, generally show lower cognitive or adaptive behavior skills, while those with mUPD may have better developed verbal than spatial skills, and are more apt to have autism, autistic features and psychosis (Boer et al., 2002; Dykens & Roof, 2008; Key et al., 2013; Whittington et al., 2005).

Growth hormone deficiency and short stature are salient in PWS, and in 2000 the Food and Drug Administration approved growth hormone treatment (GHT) for children with this syndrome. The physical benefits of GHT have been well established in >30 randomized or controlled studies of children with PWS. These include reduced body fat and increased lean muscle mass, linear growth, agility, muscle strength, coordination, and exercise tolerance (Deal et al., 2013). Consensus practice guidelines for administering GHT include monitoring children’s rate of growth, body mass index (BMI), bone density, upper respiratory function, sleep apnea, and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-I), lipid, glucose and hormonal levels (Deal et al., 2013; Emerick & Vogt, 2013).

Although GHT is also associated with cognitive benefits in other patient groups, previous studies in PWS understandably focused on endocrine and metabolic outcomes. Cognitive benefits of GHT are attributed, among other mechanisms, to the presence IGF-I and growth hormone receptors found in brain structures involved in cognition, including the hippocampus, putamen, hypothalamus and cortex (e,g, Castro et al, 2000). GHT is specifically thought to lead to a cascade of effects that strengthen long-term potentiation, neuronal signaling and plasticity in hippocampal and other brain regions (Nyberg, 2000). Among patients with diminished growth hormone production (e.g., those with pediatric growth hormone deficiency, traumatic brain injuries, aging adults and older adults with mild cognitive impairment), growth hormone replacement therapies lead to improved attentiveness, working memory, episodic memory, and verbal and nonverbal memory (Falletia, Maruffa, Burman & Harris 2006; Nyberg & Hallberg, 2013). Further, treated versus untreated growth hormone deficient rats show significantly improved spatial learning, memory, and faster learning acquisition (Nyberg & Hallberg, 2013).

Even so, only a few studies have assessed the effects of GHT on cognitive or behavioral functioning in PWS. Behaviorally, improvements in the physical domain of a health quality of life measure were found in 15 treated versus 11 untreated children with PWS over a 2 year period, with parents reporting continued physical improvements during an 11 year follow-up (Bakker, Siemensma, van Rijn, Festen & Hokken-Koelega, 2015). In early randomized trials, growth hormone treated versus untreated infants with PWS showed an earlier age of sitting and walking independently, and they scored higher on standardized tests assessing language, motor and mental development (Festen et al., 2008; Myers et al., 2006).

It is unclear, however, if gains in treated infants are sustained over the course of development, and findings to date are contradictory. Bohm and colleagues (2015) randomized 17, 3 to 11 year old children with PWS into GHT or untreated groups and found no cognitive effects after one year. The untreated group then received a double dosing of GHT, and after a year, treatments for all children were abruptly ended for 6 months. During treatment interruption parents reported deteriorations in their children’s behavior, mood and energy; cognition, however, was not re-assessed. In contrast, Siemensma and colleagues (2012) randomized 50, 4 to 14 year old children with PWS into growth hormone treated versus untreated groups, and assessed them with two cognitive tasks at baseline, and 2 to 4 years later. After two years, the treated group showed stable test scores, while controls declined. After 4 years, the treated group showed improvements relative to baseline on the verbal reasoning and visuospatial tasks.

These PWS studies raise several important methodological concerns. GHT is now recommended for all children with genetically confirmed PWS. As such, it is no longer feasible to conduct a randomized study in which a recommended treatment with known salutatory effects is withheld or postponed (West et al., 2008). Such efforts are not likely to be well received by parents, and University Institutional Review Boards would likely object to studies that withhold a recommended treatment in a vulnerable population.

Second, studies on child cognition need to control key variables that are associated with child cognition in general, especially such socio-economic factors as family income and parental education (Dickens & Flynn, 2001; Turkheimer et al., 2001). Doing so is especially relevant in the current study, as GHT remains an expensive, multi-year course of treatment. Uneven access to GHT may occur in the US due to variable health insurance coverage and/or inability to pay for treatments in lower-income families.

Third, two medical issues associated with impaired cognition in the general population are also salient in PWS. Obstructive sleep apnea, seen in the majority of children with PWS (Camfferman et al., 2006; Sedky et al., 2014), is linked to impaired attention, memory, and executive functioning in children and adults (Saunamäki & Jehkonen, 2007). Second, many individuals with PWS take psychotropic medications to treat their behavioral or psychiatric problems, with side effects that can include cognitive blunting, sedation or memory problems (Garcia et al., 2012). As such, the current study determined if these variables were associated with cognition, and if so, would need to be controlled for in analyses.

This three -part study drew subgroups of participants from a large cohort pool of 173 children and youth with genetically confirmed PWS aged 4 to 21 years who naturalistically varied in their exposures to GHT. In Study I, we compared cognitive and adaptive functioning across age-matched children who had never received GHT to those who were on GHT for 1 or more years. We hypothesized that the GHT versus treatment naïve group would have higher IQ and adaptive behavior standard scores.

As children begin GHT at different ages, Study II determined if age of treatment onset or duration of treatment was associated with cognition or adaptive behavior in 127 treated children. In light of previous infant studies, we predicted that earlier ages of beginning treatment would confer some cognitive or adaptive benefit over later starting children. Study III used multilevel model analyses to longitudinally examine changes in cognitive and adaptive functioning in children who were evaluated from one to 3 times over a 2 to 5 year period, and were consistently on versus off GHT during this time period. We expected that IQ scores would remain relatively stable in both groups, with children on (versus off) GHT sustaining their cognitive advantage over time.

Methods

Participants

A cohort of 173 well-characterized children and youth with genetically confirmed PWS aged 4 to 21 years were differentially analyzed across Study I, II and III. Children averaged 10.10 years (SD=4.85), 49% were males, and all had genetically-confirmed diagnoses of PWS (55% paternal deletions; 37% mUPD, 8% Other). At the time of study enrollment, most children (n=130) had been receiving GHT for 1 or more years, and 43 had never received GHT. Specific child and family characteristics of participants are described below for each study.

Families were recruited from across the US into our longitudinal research program on PWS regardless of their child’s GHT status. The research program does not deliberately seek treated or untreated children but instead gathers growth hormone information as part of the study protocol. GHT was not managed by study personnel, but by endocrinologists in participants’ local communities throughout the US. Families of children who never received GHT were provided information and referrals to endocrinologists for evaluations.

Procedures and measures

Following standard University IRB procedures, parents provided written, informed consent, and individuals with PWS gave their written, informed assent. Children or youth were individually administered a test battery while parents were separately interviewed, and the following measures were included in the current study.

Demographic and Health Questionnaire

Identified parental and child age, gender, PWS genetic subtype (verified through laboratory reports or confirmatory genetic testing), history and status of GHT, health history (sleep problems, medical illnesses, psychotropic and other medications), as well as family income, race/ethnicity and parental employment and education.

Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-2. (Kaufman & Kaufman, 2004; K-BIT-2)

This standardized IQ test was developed for research and screening purposes, with a mean score of 100 (SD=15). The K-BIT-2 assesses Verbal and Nonverbal cognition in people aged 4 through 90 years, and is frequently used in neurodevelopmental disabilities research. It has excellent psychometric features, including test-retest reliability of the Composite (r=.90), Verbal (r=.91) and Nonverbal IQ scores (r=.83).

Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-II. (Sparrow et al., 2005)

A widely used, semi-structured interview, the Vineland assesses the performance of everyday skills required for personal and social self-sufficiency in an overall Composite and three domains: Communication (consisting of expressive, receptive and written sub-domains), Daily Living Skills (personal, domestic and community sub-domains) and Socialization (interpersonal relationships, recreation and leisure, and coping skills sub-domains). A Motor Skills Domains (fine, gross) is administered for children up to age 6 years. The Vineland yields domain and composite standard scores (M = 100; SD = 15) that were used in analyses.

Hyperphagia Questionnaire

This was developed to measure hyperphagic behavior, drive and severity in PWS (Dykens et al., 2007). It has a robust factor structure and adequate psychometric properties. Items are rated on a 5-point scale, with higher scores indicating more hyperphagic symptoms. Analyses used total scores derived from two of the three domains: hyperphagic behavior (e.g., how often sneak food) and hyperphagic drive (e.g. how upset if denied food). We included this measure as Böhm et al. (2015) found that food seeking increased when their participants were taken off of GHT.

The Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R)

The RBS-R assesses a wide range of repetitive behaviors in people with developmental disabilities (Bodfish et al., 2000). Informants complete 43 items using a four-point scale from 0 (behavior does not occur) to 3 (behavior is a severe problem) that are divided into six subscales. This study used RBS-R total scores, with higher scores indicating more severe problems. We included it as previous studies note diminished behavior problems in growth hormone treated children with PWS.

Study I: Comparing GHT Naïve versus treated children

Participants

To provide a rigorous evaluation of cognitive or adaptive effects of GHT, Study I compared 32 treatment naïve children who had never received GHT matched on chronological age to 64 peers who were currently receiving GHT, and had been treated for 1 or more years. (As GHT was more common in younger children, we could not match 11 older, untreated individuals). A fixed-ratio, 1:2 matching design was used (Hennessey et al., 1999) such that treatment naïve participants were matched on chronological age to two, same-aged peers receiving GHT. Using power estimates based on an allocation ratio of 2, we calculated a minimum sample size of 42 treated and 22 untreated children to detect a large effect size (.80) at p<.05, using two-sided tests. The study was thus adequately powered.

The 96 participants (32 untreated; 64 treated) ranged in age from aged 4 to 21 years, with a mean of 12.45 and 12.07 in those off versus on GHT, respectively. As shown in Table 1, treatment naive and treated groups also did not differ in gender or PWS genetic subtypes.

Table 1.

Study I child demographics across GHT versus treatment naïve PWS groups.

| On GHT | Treatment Naive | X2 or t, p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 12.48 (4.29) | 12.07 (4.35) | .52 |

| % Male | 50% | 53% | .90 |

| Genetic Subtypes: | 6.41 | ||

| Type I Deletion | 18% | 15% | |

| Type II Deletion | 31% | 35% | |

| mUPD | 35% | 40% | |

| Other | 16% | 10% | |

| BMI | 23.67 (7.58) | 30.84 (7.57) | 4.01*** |

| Weight, pounds | 53.11 (24.78) | 67.23 (24.24) | 2.43** |

| Duration of GHT - years | 7.92 (3.88) | NA |

Notes:

p < .01;

p < .001.

Results

Study 1

Preliminary covariate analyses

Of the proposed potentially significant confounds, Chi-square’s and ANOVAs revealed that GHT status was significantly associated with family income and maternal education. Those on GHT had more educated, higher income families. For example, Table 1 shows that 56% of families with children on GHT were at the highest annual income level, approximately 4 times the rate of those not on GHT (14%). Family income and maternal education were thus used as covariates in all subsequent analyses. In addition to significance tests, Cohen’s d was calculated to index effect sizes for Studies I and II, using the traditional formula (d=M1−M2/σpooled.)

Other possible covariates (BMI, gender, race, sleep apnea or medications) were not significantly associated with cognitive or adaptive functioning. Even so, we conducted an additional statistical check on racial status, and also ensured that the two groups did not differ in medical problems (e.g., respiratory dysfunction, severe scoliosis) that may have precluded GHT in the treatment naïve group and perhaps confounded results on adaptive functioning. Age-corrected partial correlations between BMI, cognition and adaptive functioning were non-significant, and re-analyzing data with BMI as a covariate did not alter findings.

IQ and adaptive behavior

ANCOVAs (with income level and maternal education as covariates) assessed KBIT-2 IQ and Vineland Adaptive Behavior standard scores across age-matched treated versus treatment naïve groups. As shown in Table 3, relative to the untreated group, those on GHT had significantly higher Verbal IQ and Composite IQ scores. Differences between treated and untreated groups reflected large effect sizes for Verbal and Composite IQs (d’s=.85 and .70, respectively). ANCOVA’s further revealed that the treated group had significantly higher scores on the Vineland’s Communication (d =.52) and Daily Living Skills domains (d=.65); see Table 3. Although racial diversity was relatively low in this sample (17%), most of these families were in the treatment naïve group and were primarily bi-racial (see Table 2). Therefore, we repeated these analyses with just the Caucasian participants; the pattern of findings remained the same.

Table 3.

Study 1 IQ and adaptive behavior scores across GHT and treatment naïve groups.

| On GHT | Treatment Naive | F, p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KBIT-2: | |||

| Verbal IQ | 81.64 (15.65) | 67.54 (13.60) | 6.77** |

| Nonverbal IQ | 72.40 (17.50) | 63.83 (18.11) | 2.50 |

| Composite IQ | 74.57 (16.44) | 62.31 (15.30) | 6.30** |

| Vineland Scales: | |||

| Communication | 79.57 (14.12) | 65.05 (17.31) | 2.72* |

| Daily Living Skills | 76.88 (17.86) | 63.45 (15.77) | 3.27* |

| Socialization | 76.83 (16.81) | 64.17 (14.82) | 1.47 |

| Adaptive Composite | 77.79 (14.39) | 64.40 (13.89) | .89 |

| Hyperphagia Questionnaire | 15.99 (3.30) | 17.93 (2.79) | .26 |

| Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised | 36.63 (16.26) | 42.11 (18.79) | .69 |

Notes:

p < .05;

p < .01.

Table 2.

Study I family demographics across GHT and treatment naïve PWS groups.

| On GHT | Treatment Naive | X2 or t, p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age | 42.09 | 44.37 | 2.34 |

| Maternal Education: | 13.73** | ||

| < High School | 0 | 2% | |

| High School | 23% | 47% | |

| 2 year College | 14% | 22% | |

| 4 year College | 27% | 17% | |

| Graduate/Professional | 36% | 12% | |

| Paternal Age | 43.64 | 46.36 | 5.05 |

| Paternal Education: | 6.60 | ||

| < High School | 4% | 8% | |

| High School | 28% | 41% | |

| 2 year College | 14% | 14% | |

| 4 year College | 27% | 21% | |

| Graduate/Professional | 27% | 10% | |

| Annual Income: | 25.88*** | ||

| < $29,0000 | 6% | 20% | |

| 30–$49,000 | 4% | 23% | |

| 50–$69,000 | 21% | 20% | |

| 70–$99,000 | 13% | 23% | |

| >$100,000 | 56% | 14% | |

| % White | 94% | 71% | 9.57* |

| % Other | 2% Black, 2% Asian, 2% Bi-racial |

7% Black, 3% Hispanic, 19% Bi-racial |

|

| % Single Parent | 12% | 29% | 9.54** |

Notes:

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Hyperphagia, BMI and repetitive behaviors

ANCOVA’s showed no significant effects of GHT status on hyperphagic or repetitive behaviors (see Table 3). Consistent with previous studies, both BMI and weight were significantly lower in the treated group.

Study II: Age of treatment onset and treatment duration

Participants and procedures

Study II included 130 children and youth with PWS aged 4 to 21 years (48% males; 52% females) who had been receiving GHT for at least a 1-year duration prior to their study enrollment. On average, this group began GHT at 2.96 years of age (SD=3.47) and was on GHT for an average of 6.20 years (SD=3.45). While many children were generally receiving the recommended GHT dose of 1 mg/m2/day [7], standard of care also dictates variable dosing that depends on the child’s age, medical profile, response to treatment and clinical evaluation (Deal et al., 2013).

Children averaged 8.36 years (SD= 3.51) and the majority of them (87%) began GHT before 5 years of age. As such, they were divided into three age groups based on the age they began GHT: <1 year of age (n=38), between 1 to 2 years (n=42), and 3 to 5 years of age (n=34). The remaining children began GHT between 5 to 10 years (n=9) or in adolescence (n=7), and were excluded from analyses, leaving 114 children included in the three age groups.

Study II results

Unexpectedly, girls were less likely than boys to be placed on GHT at <1 year of age (22% versus 46%, Table 4). This treatment lag may relate to the older mean age of PWS diagnosis in girls in our study cohort (9.8 months) versus boys (5.7 months). Follow-up analyses did not reveal any gender differences in cognition or adaptive functioning.

Table 4.

Study II demographics and mean (SD) K-BIT-2 scores across age groups of beginning GHT.

| Age Group of Beginning GHT | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1 year | 1 to 2 years | 3 to 5 years | F or X2, p | |

| Current Age | 6.85 (3.02) | 8.04 (3.01) | 10.19 (4.52) | 7.75** |

| Duration GHT (Years) | 6.14 (2.78) | 6.16 (3.02) | 6.58 (4.55) | 1.61 |

| BMI | 18.45 (3.63) | 20.43 (4.04) | 22.11 (6.99) | 1.38 |

| % Males | 46% | 32% | 22% | 7.18* |

| % Females | 22% | 42% | 36% | |

| K-BIT-2 VIQ | 85.61 (14.81) | 79.57 (15.80) | 81.03 (13.08) | 1.51 |

| K-BIT-2 NVIQ | 79.86 (13.87) | 67.92 (15.66) | 69.41 (14.87) | 5.42** |

| K-BIT-2 IQ Composite | 82.58 (14.81) | 70.55 (15.11) | 72.09 (13.47) | 5.72** |

Note:

p<.05;

p<.01.

Controlling for SES and also for children’s current ages, ANCOVAs revealed that those who began GHT in the <1 year age group had significantly higher Nonverbal IQ scores than both of the older age groups (d’s=.81 and .80, see Table 4). Similarly, the infant group had higher Composite IQ’s than children beginning GHT in the two older age groups (d’s=.73 and .77). No significant effects were found for age group of beginning GHT and KBIT-2 Verbal IQ other measures. Mean Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scores were highest in the infant versus two later starting groups, yet these differences were not statistically significant after accounting for children’s current chronological ages.

Partial correlations were conducted to explore relationships between duration of GHT and cognitive and adaptive functioning. As duration is contingent upon both children’s current age and the age at which they began treatment, these were added to income and maternal education as covariates in partial correlations. Treatment duration was associated with KBIT-2 Verbal, Nonverbal and Composite IQ scores (r=.23, .25 and .25, respectively, p’s< .01). More robust relations were found between treatment duration and the Vineland’s Communication Domain (r=.72, p<.001) and Daily Living Skills (r=.45, p< .001), but not the Socialization Domain (r=.13).

Study III: Longitudinal analyses of treated versus untreated children

Participants

The longitudinal study included all 173 participants (M age = 10.10 years, SD = 4.85) who were assessed from 1 to 3 times over a 4–5 year period. Of these, 130 were on GHT and 43 were treatment naïve. Longitudinal participants were evaluated upon study enrollment and 2 to 4 years later. The average ages of children on GHT at time 1, 2 and 3 were 8.53, 10.91 and 15.16 years, respectively, while those not on GHT averaged 13.56, 15.76 and 18.56 years. Although those on GHT were younger, age was used as a covariate in analyses. An additional 10 children either started or stopped GHT during the longitudinal study, and were not included.

Children were seen for follow-up visits depending on when they were initially enrolled in the research program, and all will eventually have the opportunity to be seen a second or third time. Even so, we ensured that children seen longitudinally thus far in the research program were similar to those seen just once in gender and genetic subtype.

Study III results

A total of 323 assessments from the 173 participants were evaluated in multilevel modeling using Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM 6; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Raudenbush, Bryk & Congdon, 2001). Of the 173 children, 150 were followed over a 2 to 4 year period, including 103 seen twice and 47 seen three times. Multilevel longitudinal modeling is well suited for such data as it takes advantage of all available observations. Those seen once contribute to intercept effects, while individuals with multiple evaluations yield more reliable estimates and are thus weighed more heavily in estimates of group means. As such, incomplete cases are not dropped nor are missing values imputed. Level 1 analyses estimated intercepts and slopes, with children’s initial evaluations serving as intercepts, and time coded as time 1=0, Time 2=1, Time 3=2. In level 2 models, between-subjects independent variables were added as predictors of intercepts or slopes: child age, maternal education and income, which were centered on their grand means. GHT status was also entered as a predictor, centered on 0 (−.50, +.50).

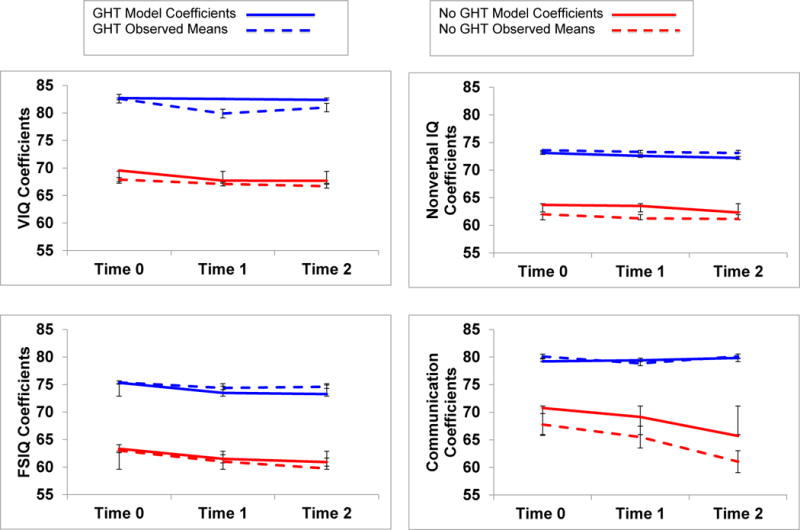

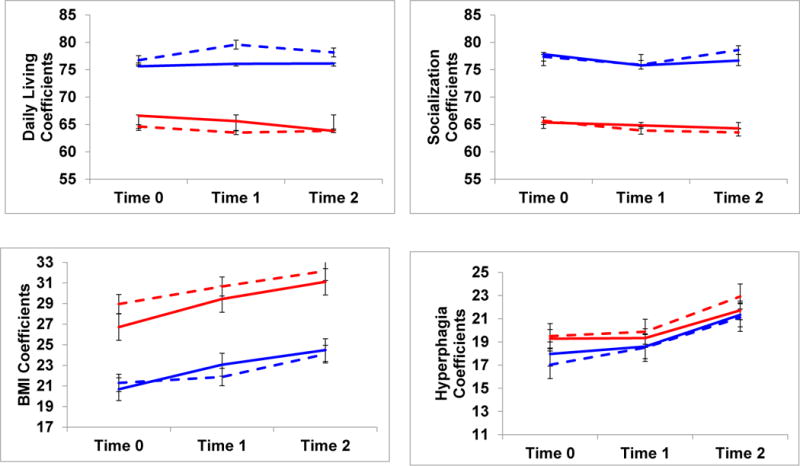

Table 5 summarizes regression coefficients and standard errors for cognitive and adaptive behavior outcomes. Significant intercept differences at Time 0 were found, with treated children scoring higher than treatment naïve children in Verbal and Full Scale IQ scores, Daily Living and Communication Skills, and lower BMI’s. No effects of GHT were found on slopes; as shown in Figure 1, each group manifested relative stability in both their modeled coefficient estimates and actual mean scores over time. Two slopes, however, were significant for the group as a whole, with both treated and untreated children showing increased BMIs and Hyperphagia Questionnaire scores over time.

Table 5.

Regression coefficients and (standard errors) of longitudinal cognitive and behavioral assessments in treated versus untreated groups.

| Verbal IQ | Nonverbal IQ | Total IQ | Communication | Daily Living | Socialization | HQ | BMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | ||||||||

| Time | 78.29*** (1.39) |

69.98*** (1.98) |

71.33*** (1.59) |

76.40*** (1.41) |

71.95*** 1.64) |

73.53 *** (1.62) |

16.65*** (.81) |

22.69*** (.79) |

| GHT (or not) | 8.84** (3.08) |

6.28 (4.86) |

7.99* (3.69) |

5.63+ (3.14) |

7.34* (3.79) |

4.07 (3.35) |

2.63 (1.92) |

−4.03** (2.05) |

| Age | −1.11*** (.26) |

−.89* (.46) |

−1.07** (.34) |

−1.22*** (.25) |

−.99** (.32) |

−1.66*** (.35) |

.50** (.17) |

.94*** (.17) |

| Slope | ||||||||

| Time | −1.79 (.70) |

−.87 (1.78) |

−1.65 (.90) |

−1.2 (.70) |

.32 (.62) |

−.39 (.72) |

1.66*** (.35) |

2.08 *** (.37) |

| GHT (or not) | −.16 (1.59) |

.68 (2.71) |

.41 (1.99) |

.42 (1.87) |

−.13 (1.47) |

.16 (1.91) |

−1.72 (.93) |

−.67 (.86) |

| Age | .48*** (.12) |

.59** (.23) |

.60** (.17) |

.35** (.13) |

.15 (.14) |

.39* (.20) |

−.17+ (.09) |

−.11 (.07) |

Notes:

p = .06;

p< .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Modeled coefficients and mean scores for cognitive and behavioral outcomes in treated versus untreated children with PWS. Children were assessed 2 years apart, and were continuously on or off GHT during this time period.

Maternal education or family income did not emerge as significant predictors of modeled intercepts or slopes, yet age had a consistent effect on both. Although no significant interaction effects were found, follow-up scatterplots indicated that when older children or adolescents started the study at Time 0, they did so with slightly lower mean IQ and adaptive behavior scores than younger children. When younger, treated children enrolled in the study, they had higher standard scores that remained high, while older treated individuals either stabilized, or improved in scores over time. In contrast, both younger and older untreated children had similarly low cognitive and adaptive scores that remained relatively stable over time.

Discussion

As randomized designs that withhold or postpone a treatment with known salutatory effects is not feasible, this three-part study instead took advantage of naturally occurring variance in GHT status in a large cohort of children and youth with genetically confirmed PWS. Using well-controlled analyses, GHT was associated with improved cognition and adaptive behavior that was sustained over time in continuously treated children. Findings are consistent with some other growth hormone deficient pediatric patient groups, and justify a need for more research on cognitive and adaptive effects of GHT in people with PWS.

Compared to treatment naïve children, age-matched children on GHT had significantly higher Verbal and Composite IQ scores, even when controlling for between-group differences in family income and maternal education. The KBIT-2 Verbal domain taps such processes as verbal reasoning, semantic memory, vocabulary comprehension and making inferences about situations. The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale’s Communication and Daily Living Skills Domain standard scores were also higher in the treated group. While the Communication domain is often associated with verbal intelligence, better-developed communication abilities as well as skills in daily self-care or chores may reflect improved alertness, energy to engage in tasks, muscle tone and motor control in the treated children. We did not expect, nor find, significant effects of GHT on hyperphagia or repetitive behaviors, but included these measures to help refine our understandings of how GHT impacts the PWS behavioral phenotype. These findings are consistent with Lo et al. (2015) who did not find significant associations between growth treatment and child behavior problems. Taken together, our findings are consistent with work in animal models and other growth hormone deficient patients that demonstrate beneficial effects of GHT on cognitive processes and using such processes in the service of everyday adaptive functioning (Falletia et al., 2006).

Our findings of an IQ advantage in growth hormone treated children with PWS differ from Böhm et al. (2015), who did not find any cognitive benefits in a sample of 17 children with PWS. Discrepant findings across studies may relate to differences in sample size and measures. The current study included larger numbers of children and youth who all received the same standardized cognitive and adaptive tests. In contrast, participants in Böhm et al.’s (2015) study did not necessarily receive the same test over time, and the tests used also varied across individual participants, which may have confounded their results.

Regarding age of treatment initiation, the majority of children began GHT before 5 years of age. No significant differences in Verbal IQ were found between children who began GHT in infancy or between 2 to 3 years or 3 to 5 years of age. However, children who began treatment at <1 year of age had a significant advantage over later-starting children in their Nonverbal and Composite IQs. The KBIT-2 Nonverbal IQ requires that respondents form relations between various stimuli, including meaningful relations between people or objects, as well as more abstract, spatial connections between symbols or designs. Intriguingly, these findings are consistent with enhanced spatial learning in treated, growth hormone deficient juvenile rats and enhanced spatial learning and memory in other patient populations (for a review, see Nyberg & Hallberg, 2013).

Experts agree that GHT in PWS should be started by age two or prior to the onset of hyperphagia and/or obesity (Deal et al., 2013). Infants with PWS, however, take approximately twice as long as typically developing infants to attain motor milestones that are crucial for brain development and learning, including stabilizing and positioning their heads, grasping, reaching, rolling over, sitting unassisted, pulling up to stand, crawling and walking (Anderson et al., 2013). Reus and colleagues (2013) found that GHT enhanced the effects of motor training in 24 infants with PWS, with earlier initiation of GHT leading to steeper rates of improvement and higher scores on motor function tests. Further, Lo and colleagues (2015) reported that compared to untreated children with PWS, those who began GHT in infancy and continued treatment for 7 years had higher developmental levels of adaptive behavior skills.

Although a compelling case can be made for beginning GHT in infancy, studies are sorely needed on GHT in adults with PWS. Compared to untreated controls, Höybye and colleagues (2005) reported that 10 adults on GHT for 6 months improved in cognitive tests of mental speed, flexibility, reaction time, and motor performance. Anecdotally, adults with PWS on GHT show improved aerobic conditioning, muscle mass, strength, attention span, energy and well being (Bertella et al., 2007; Mogul et al., 2008). Additional studies are needed to identify differential effects of GHT on cognitive processes in children versus adults with PWS.

Controlled analyses regarding duration of GHT indicated that longer treatment times were positively associated with higher cognitive and adaptive scores. However, more robust associations were found between duration and adaptive as opposed to cognitive functioning, and for conceptually sound reasons. Although GHT is associated with cognitive benefits, longer treatment courses may not necessarily yield increasingly higher and higher IQ scores. Indeed, regression to the mean suggests otherwise, and that even though GHT may boost cognition, it does so in the context of an existing developmental disorder with a lower mean IQ than the general population. Yet such adaptive skills as expressive communication, self-care and household chores, are learned behaviors that become more complex with advancing age. These practical skills depend on both motor and cognitive abilities, and are critically important functional outcomes in people with intellectual disabilities.

Study III’s longitudinal analyses extended findings from Study I by showing that group differences in cognitive and adaptive functioning were sustained over time. Continuously treated versus untreated children maintained their advantages over time in Verbal and Full Scale IQ scores, and in their adaptive Communication and Daily Living Skills. Within each group, cognitive and adaptive skills were stable over time in both modeled coefficients and actual mean scores. Different patterns, however, were found for BMIs and Hyperphagia Questionnaire scores. Although Hyperphagia Questionnaire scores did not differ across groups, both treated and untreated children had significant increases in these scores over time. Similarly, although BMI’s significantly differed across treated versus untreated participants, both groups again showed rising BMI’s over time.

Consistent with previous studies, GHT may positively impact BMI, but not necessarily hyperphagia, which is salient in PWS. As these hyperphagic children age, they are exposed to more environmental opportunities to obtain food, and to apply their more advanced cognitive or life skills in the service of finding food, often in very clever ways. Thus, regardless of GHT status, continued vigilance and supervision with diet and food is warranted as children with PWS transition into adolescence or young adulthood.

Interestingly, no significant declines in IQ scores were found in treatment naïve children. This finding is consistent with early reports showing relative stable IQs in children with PWS (Dykens et al., 1992), but differs from Siemensma et al. (2012) who instead found declines in untreated children over a 2-year period. These differences may relate to the cognitive measures used across studies. This study used a standardized IQ test; in contrast, Siemensma et al. (2012) used an algorithm to estimate IQ scores from two Wechsler subtests. Such short-form IQ tests can be particularly problematic in longitudinal studies because subtest scores have poorer test-retest reliability than fully indexed IQ scores (Kaufman & Kaufman, 2001).

This three-part study had several limitations. First, unlike earlier work, current use of random assignment in which GHT is denied or postponed is no longer feasible. We thus opted to take advantage of naturally occurring variance in GHT in a large number of children, and to control for such confounding variables as SES. As in any non-randomized study, however, there is always a chance that unknown or uncontrolled factors may have influenced our results. This possibility is tempered somewhat by a strong literature on cognitive advantages of GHT in other growth hormone deficient patients and in animal models.

Second, although Study 1 was adequately powered, the sample of treatment naïve children was smaller than treated children. As such, we lacked power to analyze possible interactions between genetic subtypes of PWS and treatment effects. We would hypothesize, however, that treated children show cognitive or adaptive advantages regardless of their genetic subtype, and that such gains may be especially salient in those with Type I deletions. Because people with Type I deletions generally have lower IQ and adaptive behavior standard scores than other subtypes, they are positioned to gain the most from GHT and move closer to the scores of their counterparts with PWS. As well, other growth hormone deficient patients with more severe impairments show the most robust cognitive improvements when receiving GHT (Moreau et al., 2013).

Third, several between and within group analyses were conducted, increasing the chances of Type I error. However, analyses were grounded in reasonable, a priori hypotheses, and all effect sizes were large or medium-to-large. An additional weakness is that GHT data were based on parent report, and aside from a few families who received care at our University Medical Center, medical records were not available to verify parent reports. Even so, parents were reliable in their reporting of GHT start or stop dates and potential treatment problems across both an interview and written health survey. Similarly, because we did not directly administer or medically monitor GHT, we did not obtain serum measures of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I). Although Siemensma et al. (2012) found no effects of serum IGF-1 levels on cognition in their participants with PWS, van Nieuwpoort et al. (2011) reported that higher IGF-I levels in 15 untreated PWS adults were associated with faster visual memory test performances. As other studies also find relationships between IGF-1 levels and magnitude of memory change (Maruff & Falleti, 2005), further work is needed to clarify these discrepant findings.

Finally, this study did not address what happens to cognitive or adaptive functioning after children with PWS stop GHT. A sizable group of children with PWS in our research program, not included in the current study, stopped GHT at different ages and for a variety of reasons: they successfully met linear growth goals, medical insurance coverage ceased or changed, parents could not afford out-of-pocket treatment expenses, or children experienced medical concerns leading to discontinuation (e.g., increased insulin levels, worsening of respiratory dysfunction). Such variability makes it hard to examine the cognitive or behavioral effects of ending treatment using an observational versus controlled study design. However, Böhm et al. (2015) stopped GHT in their participants for 6 months, during which parents reported a significant worsening of such problems as sadness, irritability, lethargy, hunger and repetitive behaviors; cognition, however, was not re-assessed. In contrast, Lo et al. (2015) reported that GHT had no measurable effects on behavior problems in PWS. Höybye et al. (2005) followed 10 adults with PWS at baseline, during and post GHT and found deteriorations in physical and social functioning 3 to 6 months after treatment ended, but again cognition was not formally re-evaluated. Future studies are especially needed that document specific cognitive changes after GHT ends in memory, attention, processing speed, and executive functioning (Maruff & Falleti, 2005).

Despite these limitations, this is the first large, well-controlled study to identify cognitive and adaptive benefits of GHT in children and youth with PWS. While it was reassuring that more children in our study cohort were receiving GHT than not, it is troubling that treatment naïve children were more likely to have less educated parents who earned lower annual incomes. Education and dissemination about GHT in PWS thus needs to target these families, as well as pediatricians and other practitioners who care for these children. Compounding these concerns are Takeda et al.’s (2010) cost/benefit analyses in several growth hormone deficient patient groups showing higher incremental costs of GHT in PWS relative to quality of years gained.

A potential boost in cognitive or adaptive functioning, however, highlights the need to revisit previous justifications for GHT in PWS based solely on linear growth or body composition. In this vein, Wass and Reddy (2010) advocate that positive effects on memory and cognition should be added to the list of benefits of GHT for all children with growth hormone deficiencies. Doing so in PWS, however, poses several pressing questions: how should cognitive or adaptive behavior benefits be juxtaposed against the expectation that GHT typically ends when children with PWS meet linear growth goals? What happens to cognition when GHT is stopped? If behavior and/or cognition are indeed proven to deteriorate, what new cost/benefit models are needed to support the safe, continued use of GHT on maintenance dosages for ancillary but important quality of life benefits? Answers require additional studies, input from families, individuals, experts and other stakeholders, and more equitable access to GHT in the PWS population.

Key points.

Growth hormone treatment (GHT) is recommended to improve linear height and body composition in all children with genetically-confirmed PWS.

Cognitive advantages of GHT are seen in other growth hormone deficient groups and animal models, but are understudied in PWS.

Growth hormone treated versus treatment naïve 4 to 21 year old children with PWS had significantly higher Verbal and Composite IQs and adaptive behavior standard scores.

Treated children sustained their cognitive advantages over a 2 to 5 year period; scores were stable in untreated children.

Future work needs to identify: what happens to cognition and adaptive behavior when GHT is stopped, neurocognitive profiles associated with GHT, and ways to ensure more equitable access to GHT in the PWS population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH EKS-NICHD Grants R0135681 and P30HD15052 and NCAT Grant UL1TR00044. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest. The authors are extremely grateful to the families who participated in our research.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- Anderson DL, Campos JJ, Witherington DC, Dah A, Rivera M, He M, et al. The role of locomotion in psychological development. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg. Article 440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker NE, Siemensma EP, van Rijn M, Festen DA, Hokken-Koelega AC. Beneficial effect of growth hormone treatment on health-related quality of life in children with Prader-Willi syndrome: A randomized controlled trial and longitudinal study. Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 2015;84:231–239. doi: 10.1159/000437141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertella L, Mori I, Grugni G, Pignatti R, Ceriani F, Molinari F, et al. Quality of life and psychological well-being in GH-treated, adult PWS patients: a longitudinal study. Journal of Intellect Disability Research. 2007;51:302–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2006.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodfish JW, Symons FJ, Parker DE, Lewis MH. Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: Comparisons to mental retardation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2000;30:237–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1005596502855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer H, Holland A, Whittington J, Butler J, Webb T, Clarke D. Psychotic illness in people with PWS due to chromosome 15 maternal uniparental disomy. Lancet. 2002;359:135. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07340-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm B, Ritzén M, Lindgren AC. Growth hormone treatment improves vitality and behavioural issues in children with Prader-Willi syndrome. Acta Pædiatrica. 2015;104:59–67. doi: 10.1111/apa.12813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camfferman D, Lushington K, O’Donoghue F, McEvoy RD. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in Prader-Willi syndrome: An unrecognized and untreated cause of cognitive and behavioral deficits? Neuropsychology Review. 2006;16:123–129. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, Driscoll DJ. Prader-Willi syndrome. Genetics in Medicine. 2012;14:10–26. doi: 10.1038/gim.0b013e31822bead0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro JR, Costoya JA, Gallego R, Prieto A, Arce VM, Señarís R. Expression of growth hormone receptor in the human brain. Neuroscience Letters. 2000;281:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)00830-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal CL, Tony M, Höybye C, Allen DB, Tauber M, Christiansen JD, the Growth Hormone in PWS Clinical Guidelines Participants Growth hormone research society workshop summary: Consensus guidelines for recombinant human growth hormone therapy in Prader-Willi syndrome. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98:E1072–E1087. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens WT, Flynn JR. Heritability estimates versus large environmental effects: The IQ paradox resolved. Psychological Review. 2001;108:346–369. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Hodapp RM, Walsh K, Nash LJ. Profiles, correlates and trajectories of intelligence in Prader-Willi syndrome. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:1125–1130. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Lee E, Roof E. Prader-Willi syndrome and autism spectrum disorders: An evolving story. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2011;3:225–237. doi: 10.1007/s11689-011-9092-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Maxwell M, Pantino E, Kossler R, Roof E. Assessment of hyperphagia in Prader-Willi syndrome. Obesity. 2007;15:1816–1826. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykens EM, Roof E. Behavior in Prader-Willi syndrome: Relationship to genetic subtypes and age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:1001–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerick JE, Vogt KS. Endocrine manifestations and management of Prader-Willi syndrome. International Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology. 2013;14:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1687-9856-2013-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falletia MG, Maruffa P, Burman P, Harris A. The effects of growth hormone deficiency and replacement on cognitive performance in adults: A meta-analysis of the current literature. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:681–691. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festen DAM, Wevers M, Lindgren AC, Böhm B, Otten BJ, Wit JM, et al. Mental and motor development before and during growth hormone treatment in infants and toddlers with Prader–Willi syndrome. Clinical Endocrinology. 2008;68:919–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G, Logan GE, Gonzalez-Heydrich J. Management of psychotropic medication side effects in children and adolescents. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2012;21:713–738. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2012.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy S, Bilker EB, Berlin JA, Strom BL. Factors influencing the optimal control-to-case ratio in matched case-control studies. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999;49:195–197. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höybye C, Thoren M, Bohm B. Cognitive, emotional, and physical, and social effects of growth hormone treatment in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2005;49:245–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JC, Kaufman AS. Time for the changing of the guard: A farewell to short forms of intelligence tests. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2001;19:245. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-2. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Key AP, Jones D, Dykens EM. Social and emotional processing in Prader-Willi syndrome: Genetic subtype differences. Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2013;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1866-1955-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo ST, Festen DAM, Tummers-de Lind van Wijngaarden RFA, Collin PJL, Hokken-Koelega ACS. Beneficial effects of long-term growth hormone treatment on adaptive functioning in infants with Prader-Willi syndrome. American Journal of Intellectual and developmental Disabilities. 2015;120:315–327. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-120.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo ST, Siemensma EP, Festen DA, Collin PJ, Hokken-Koelega AC. Behavior in children with Prader-Willi syndrome before and during growth hormone treatment: A randomized controlled trial and 8-year longitudinal study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015;24:1091–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruff P, Falleti M. Cognitive function in growth hormone deficiency and growth hormone replacement. Hormone Research. 2005;64(suppl 3):100–108. doi: 10.1159/000089325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogul HR, Lee PDK, Whitman BY, Zipf WB, Frey M, Myers SE, et al. Growth hormone treatment of adults with Prader-Willi syndrome improves body mass, fractional body fat and serum triodothyronine without glucose impairment. Journal of Clinical and Endocrinology Metabolism. 2008;93:1238–1245. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau OK, Cortet-Rudell C, Yollin E, Merlen E, Daveluy W, Rousseaux M. Growth hormone replacement therapy in patients with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Neurotrauma. 2013;30:998–1006. doi: 10.1089/neu.2012.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers SE, Whitman BY, Carrel AL, Moerchen V, Bekx MT, Allen DB. Two years of growth hormone therapy in young children with Prader-Willi syndrome: Physical and neurodevelopmental benefits. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2006;143A:443–448. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg F. Growth hormone in the brain: Characteristics of specific brain targets for the hormone and their functional significance. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2000;21:330–348. doi: 10.1006/frne.2000.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyberg F, Hallberg M. Growth hormone and cognitive function. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2013;9:357–365. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush S, Bryk T, Congdon R. Hierarchical linear and no linear modeling. Scientific Software International, Inc 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Reus L, Pelzer BJ, Otten BJ, Siemensma EPC, van Alfen-van der Velden JAAEM, Festen DAM, et al. Growth hormone combined with child-specific motor training improves motor development in infants with Prader-Willi syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013;34:3092–3103. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunamäki T, Jehkonen M. Review of executive functions in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Acta Scandinavica Neurologica. 2007;115:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedky K, Bennett DS, Pumariega A. Prader-Willi syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea: co-occurrence in the pediatric population. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2014;10:403–409. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemensma EPC, van Wijngaarden RFATL, Festen DAM, Troeman ZCE, van Alfen-van der Velden AEMJ, Otten BJ, et al. Beneficial effects of growth hormone treatment on cognition in children with Prader-Willi syndrome: A randomized controlled trial and longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012;97:2307–2314. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Balla DA. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-II. Minneapolis, MN: Pearson Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: A review and a look forward. Statistical Science. 2010;25:1–21. doi: 10.1214/09-STS313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda A, Cooper K, Bird A, Baxter L, Frampton GK, Gospodarevskaya E, et al. Recombinant human growth hormone for the treatment of growth disorders in children: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technology Assessment. 2010;14(42) doi: 10.3310/hta14420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkheimer E, Haley A, Waldron M, D’Onofrio B, Gottesman I. Socioeconomic status modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychological Science. 2001;14:623–628. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nieuwpoort IC, Deijen JB, Curfs LMG, Drent ML. The relationship between IGF-I concentration, cognitive function and quality of life in adults with Prader–Willi syndrome. Hormones and Behavior. 2011;59:444–450. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wass JAH, Reddy R. Growth hormone and memory. Journal of Endocrinology. 2010;207:125–126. doi: 10.1677/JOE-10-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Duan N, Pequegnat W, Gaist P, Des Jarlais DC, Holtgrave D, et al. Alternatives to the randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98:1359–1366. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.124446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittington J, Holland A, Webb T, Butler J, Clarke D, Boer H. Cognitive abilities and genotype in a population-based sample of people with Prader-Willi syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2004;48:172–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2004.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]