Abstract

Objective

To identify factors associated with rural sepsis patients’ bypassing rural emergency departments (EDs) to seek emergency care in larger hospitals, and to measure the association between rural hospital bypass and sepsis survival.

Design, Setting, and Patients

Cohort study of adults treated in EDs of a rural Midwestern state with severe sepsis or septic shock between 2005 and 2014, using administrative claims data. Patients residing ≥ 20 miles from a top-decile sepsis volume hospital and < 20 miles from a local hospital were included.

Interventions

Patients bypassing local rural hospitals to seek care in larger hospitals.

Measurements and Main Results

A total of 13,461 patients were included, and only 5.4% (n = 731) bypassed a rural hospital for their ED care. Patients who initially chose a top-decile sepsis volume hospital were younger (64.7 vs. 72.7 y, p<0.001) and were more likely to have commercial insurance (19.6% vs. 10.6%, p<0.001) than those who were seen initially at a local rural hospital. They were also more likely to have significant medical comorbidities, such as liver failure (9.9% vs 4.2%, p<0.001), metastatic cancer (5.9% vs 3.2%, p<0.001), and diabetes with complications (25.2% vs. 21.6%, p=0.024). Using an instrumental variables approach, rural hospital bypass was associated with a 5.6% increase (95%CI 2.2 – 8.9%) in mortality.

Conclusions

Most rural patients with sepsis seek care in local EDs, but demographic and disease-oriented factors are associated with rural hospital bypass. Rural hospital bypass is independently associated with increased mortality.

Keywords: sepsis, rural health services, hospitals, rural, emergency medical services, emergency service, hospital, rural population

Introduction

Severe sepsis is responsible for 390,000 emergency department (ED) visits annually (1) and has a mortality rate of over 24%.(2) Early targeted therapy, provided in the ED, can improve survival (3), but this care is not provided consistently across community EDs.(2, 4) There is poor adherence to Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines (5) in sepsis patients treated in low-volume hospitals, which may explain the increased mortality risk for these patients.(6) This increased mortality remains true even for patients transferred from rural hospitals to high volume centers.(7) Rural hospitals have unique challenges in providing high-quality critical care (8), yet patients value proximity to home when deciding where they seek inpatient care.(9) This suggests that improving care delivery for sepsis patients presenting to rural community hospitals is an urgent need.

Financial factors, transportation factors, perceived quality, and convenient access to care are all influential factors for patients in choosing the hospital where they seek care.(10–13) With respect to emergency care, perceived quality of care, wait times, comorbidities, and severity of illness all have been shown to contribute to the choices patients make in choosing an ED,(14–16) and some of these factors also contribute to clinical outcomes.(17, 18) Previously, investigators have shown that rural patients bypass local rural hospitals in up to 30–50% of cases (19–25), but this has not been studied for critically ill patients with severe sepsis. As delays in sepsis care are associated with mortality (3, 26, 27) and are more frequent in rural sepsis patients(4), defining influential factors related to bypass is vital in order to devise systems to improve care of rural sepsis patients.

The objective of this study is to describe where rural patients with severe sepsis or septic shock seek emergency care. The secondary objective is to define factors that contribute to patients bypassing rural EDs, to elucidate how these factors influence the probability of inter-hospital transfer, and to measure the association between rural hospital bypass and clinical outcomes.

Materials and Methods

This study is a cohort analysis of administrative billing claims of all adults (18 years or older) treated in Iowa EDs for severe sepsis or septic shock from 2005–2014. The Iowa Hospital Association Inpatient and Outpatient data sets were used to create a linkage across inter-hospital transfer using a probabilistic linkage algorithm that used date of birth, sex, patient zip code, county of residence, and date of visit through a sequential matching algorithm, using social security number to break non-matching linkages. Social security numbers were maintained on a secure server accessible only to the study statistician and were used only for the purposes of the linkage; this variable was removed from the analysis data set for security. Ten percent of records were manually verified to confirm appropriate linkages. This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board under waiver of informed consent.

Definitions

Severe sepsis was identified using a previously validated definition based on inpatient diagnosis codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 9th edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)(28), while having a qualifying infection diagnosis at the time of the ED evaluation. Comorbidities were defined using the Elixhauser methodology, a set of 30 comorbid conditions defined by ICD-9-CM codes that have been shown to predict mortality, hospitalization, and health care utilization.(29, 30) Rurality was defined using Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) codes,(31) which is an accepted form of classifying census tracts by population density, urbanization, and daily commuting.(32)

Top-decile sepsis volume hospitals were defined as hospitals in the top decile of inpatient sepsis volume. The rural choice cohort was defined as patients who had a local hospital within 20 miles of their residence, but that hospital was not a top-decile sepsis volume hospital, and there was no top-decile hospital within 20 miles of the patient residence. These patients were felt to have a choice of where they would receive their emergency care.

Driving Distances

Driving distances were estimated using geocoded hospital locations from each hospital street address to the centroid of the zip code of residence, using the GoogleMaps Application Programming Interface (API).(33)

Outcomes

The primary analysis was to describe the proportion of rural choice cohort patients who bypass a local hospital and to identify factors associated with rural hospital bypass. The primary outcome was hospital mortality, and secondary outcomes included subsequent inter-hospital transfer, and the association between rural hospital bypass and hospital length-of-stay.

Analysis

Patients in the rural choice cohort were divided into (1) those who sought care at their local hospital and (2) those who bypassed their local hospital. Bypass rate was calculated as a proportion, and demographics, insurance status, comorbidities, and clinical outcomes were compared in univariate analysis using the t-test, Wilcoxon rank-sum test, and the chi-squared test, as appropriate.

Multivariable Regression Model

To determine factors associated with rural hospital bypass, a multivariable explanatory logistic regression model was created, including factors from the univariate analysis. Variables were selected for inclusion based on statistical criteria (p<0.20), then screened for clinical relevance prior to inclusion (because statistical significance can be misleading in large populations). Nonsignificant covariates were retained in the model if two investigators agreed they were of clinical importance. Collinearity and interactions were evaluated with each variable. Using the same analysis approach, a second multivariable logistic regression model was developed to measure the effect of rural hospital bypass on hospital mortality.

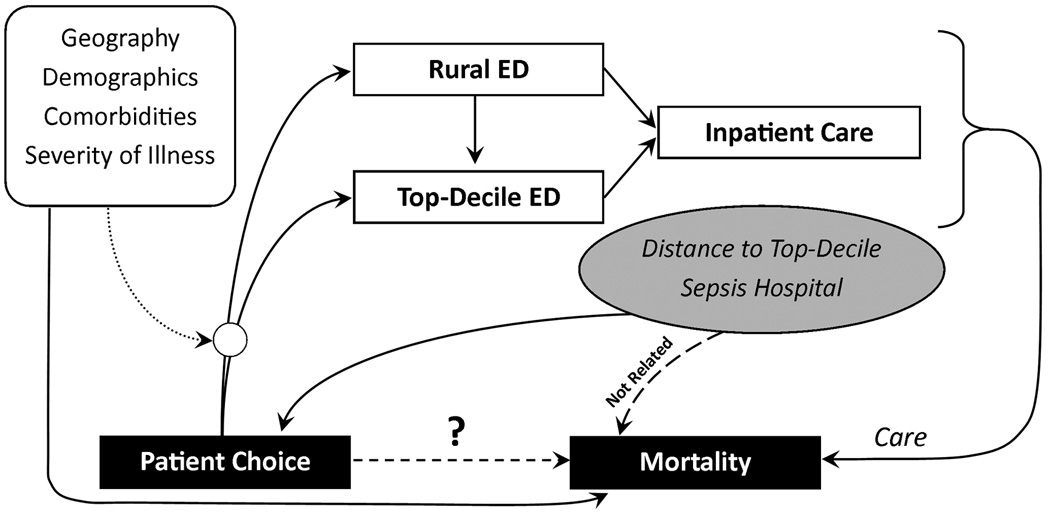

Instrumental Variables Model

Because no physiologic severity of illness indices were available in the administrative data set, sepsis severity could have been a significant unmeasured confounder in explaining mortality. To account for this missing variable, an instrumental variables approach was used. Distance to a top-decile sepsis volume hospital was used as the instrument to predict rural hospital bypass. This variable meets the assumptions of an instrumental variable because (1) increasing distance from residence to a top-decile hospital is inversely associated with rural hospital bypass (F-statistic=623.5), and (2) the exclusion restriction applies because no other plausible relationship exists between distance and death, except through access to care. This model assumes that severity of illness is uniformly distributed over geography, and there exists no theoretical or empiric basis upon which to refute that assumption (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Conceptual model including instrumental variables analysis.

Patients choose whether to be treated in a rural emergency department (ED) or a top-decile sepsis volume ED, but that decision is influenced by several factors, including geography, demographics, comorbid conditions, and illness severity. After arriving to their ED of choice, patients may be admitted directly to the hospital or transferred to another hospital for admission. The care provided during the ED and inpatient stay influences mortality, but measurable and unmeasurable variables that influenced patient choice also influence mortality. Distance to a top-decile sepsis volume hospital is proposed as an instrumental variable because it is clearly associated with patient choice, but should not be associated with mortality except through the care and choices that patients make in where they receive their care. In that way, the instrument can be used to understand the role of patient choice in influencing care and ultimately the causal relationship between patient choice and mortality.

Driving Distance Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the effect of driving distance on hospital choice. To do so, a series of rural choice cohorts were defined iteratively using alternative distance thresholds (e.g., 25 miles, 30 miles, etc.). For instance, patients were identified who live within 30 miles of a local hospital, but not within 30 miles of a top-decile sepsis volume hospital and a rate of rural hospital bypass was calculated. This analysis was reported graphically by the proportion of patients bypassing rural hospitals using each cohort definition. All statistical analyses were completed using SAS v.9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) or Stata v.13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas), and this study is reported in accordance with the Strengthening The Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement.(34)

Results

Over the 10-year period, 13,461 comprised the rural choice cohort (Supplemental Figure 1). Most patients (94.6%) sought care initially in their local hospital. We are unable to determine why patients chose to bypass their local hospital, and many may have chosen to seek care in a tertiary hospital because of health insurance or prior care for chronic medical conditions. Most patients (60%) were transferred, even among those who bypassed rural hospitals (52%). Bypass patients were more frequently transferred after hospital admission as part of their inpatient stay rather than directly from the ED (65% vs. 30%, p<0.001).

In this cohort, top-decile hospitals included the 12 hospitals that averaged more than 25 inpatient severe sepsis admissions annually.

Factors Associated with Rural Bypass

Patients who bypassed local rural hospitals were younger (p<0.001), more likely to have commercial insurance (p<0.001), and had more medical comorbidities than those initially seen in a local hospital (Table 1). Even restricting to patients younger than 65 (who would not be categorically eligible for Medicare), rural bypass patients were still more likely to have commercial insurance (37% vs. 32%, p<0.001). Using a multivariable logistic regression model, the following factors were associated with increased rural hospital bypass: decreasing age; commercial insurance (relative to Medicare or uninsured); a source of infection other than pneumonia, urinary infection, or cellulitis; comorbidities; and decreasing distance to a top-decile sepsis volume hospital (Table 2).

Table 1.

Demographics, comorbidities, and clinical outcomes stratified by rural bypass status.

| Factor | Treated in Local Hospital (n = 12,730) |

Bypassed Local Hospital (n = 731) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y (mean, SD) | 72.7 (15.4) | 64.7 (15.9) | < 0.001 |

| 18 – 50 y, n (%) | 1245 (10) | 146 (20) | < 0.001 |

| 51 – 69 y, n (%) | 3502 (28) | 291 (40) | |

| 70 – 81 y, n (%) | 3903 (31) | 178 (24) | |

| Over 82 y, n (%) | 4080 (32) | 116 (16) | |

| Non-White, n (%) | 167 (1) | 14 (2) | 0.179 |

| Male, n (%) | 6337 (50) | 389 (53) | 0.071 |

| Rural Residence31, n (%) | 11660 (92) | 604 (83) | < 0.001 |

| Primary Source of Health Insurance | < 0.001 | ||

| Medicare, n (%) | 10251 (81) | 458 (63) | |

| Medicaid, n (%) | 656 (5) | 85 (12) | |

| Commercial, n (%) | 1351 (11) | 143 (20) | |

| Uninsured, n (%) | 404 (3) | 23 (3) | |

| Source of Infection28 | |||

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 4790 (38) | 210 (29) | < 0.001 |

| Urinary Tract Infection, n (%) | 3150 (25) | 106 (15) | < 0.001 |

| Cellulitis and Soft Tissue Infection, n (%) | 884 (7) | 61 (8) | 0.150 |

| Other, n (%) | 4296 (34) | 369 (51) | < 0.001 |

| Surgery During Hospitalization (Broad Definition)50, n (%) | 805 (6) | 69 (9) | 0.001 |

| Comorbidities‡ (Elixhauser methodology)30 | |||

| Congestive Heart Failure, n (%) | 3243 (25) | 192 (26) | 0.634 |

| Valvular Heart Disease, n (%) | 897 (7) | 82 (11) | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease, n (%) | 1233 (10) | 94 (13) | 0.005 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 6880 (54) | 421 (58) | 0.061 |

| Neurologic Disorders, n (%) | 1638 (13) | 87 (12) | 0.447 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease, n (%) | 3539 (28) | 208 (28) | 0.701 |

| Diabetes Mellitus with Complications, n (%) | 3381 (27) | 202 (28) | 0.024 |

| Renal Failure, n (%) | 3313 (26) | 194 (27) | 0.758 |

| Liver Disease, n (%) | 539 (4) | 72 (10) | < 0.001 |

| Metastatic Cancer, n (%) | 404 (3) | 43 (6) | < 0.001 |

| Inter-Hospital Transfer, n (%) | 7739 (61) | 381 (52) | < 0.001 |

| Inpatient Transfer, n (% among transfers) | 2321 (30) | 249 (65) | < 0.001 |

| Distance | |||

| First Hospital, miles (SD) | 7.3 (11.6) | 58.7 (36.4) | < 0.001 |

| Admitting Hospital, miles (SD) | 40.9 (39.2) | 50.7 (43.4) | < 0.001 |

| Top-Decile Sepsis-Volume Hospital, miles (SD) | 55.1 (25.1) | 41.1 (18.3) | < 0.001 |

| Transfer Distance, miles (SD) | 40.2 (46.7) | 42.1 (54.0) | 0.286 |

| Critical Access Hospital, n (%) | 10413 (82) | 0 (0) | < 0.001 |

| Outcomes | |||

| Hospital Length-of-Stay, median (IQR) | 6 (3–11) | 10 (5–18) | < 0.001 |

| Died, n (%) | 2123 (17) | 153 (21) | 0.003 |

y, year; SD, standard deviation; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; IQR, interquartile range

For brevity, not all Elixhauser comorbidity variables are listed. The remaining variables either had very low prevalence or had no significant differences between cohorts.

All numbered references in this table refer to reference numbers from the main manuscript.

Table 2.

Multivariable models predicting rural hospital bypass and mortality.

| Rural Hospital Bypass | Mortality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95%CI) |

p | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95%CI) |

P |

| Age (per decade) | 0.804 (0.753 – 0.857) | < 0.001 | 1.121 (1.074 – 1.170) | < 0.001 |

| Non-White | 0.855 (0.482 – 1.517) | 0.593 | 1.171 (0.793 – 1.731) | 0.427 |

| Male | 1.036 (0.880 – 1.220) | 0.669 | 0.873 (0.792 – 0.963) | 0.007 |

| Rural Residence31 | 0.597 (0.476 – 0.749) | < 0.001 | 1.159 (0.964 – 1.392) | 0.116 |

| Primary Source of Health Insurance | < 0.001 | 0.061 | ||

| Medicare | 0.691 (0.546 – 0.877) | 1.042 (0.872 – 1.245) | ||

| Medicaid | 1.060 (0.781 – 1.437) | 1.167 (0.906 – 1.503) | ||

| Commercial | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | ||

| Uninsured | 0.485 (0.299 – 0.788) | 1.489 (1.100 – 2.015) | ||

| Source of Infection28 | ||||

| Pneumonia | 0.686 (0.569 – 0.828) | < 0.001 | 0.647 (0.580 – 0.721) | < 0.001 |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 0.554 (0.436 – 0.706) | < 0.001 | 0.320 (0.277 – 0.371) | < 0.001 |

| Cellulitis and Soft Tissue Infection | 0.876 (0.646 – 1.187) | 0.392 | 0.353 (0.277 – 0.453) | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities (Elixhauser methodology)30 | ||||

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1.170 (0.963 – 1.420) | 0.114 | 1.315 (1.177 – 1.470) | < 0.001 |

| Valvular Heart Disease | 1.555 (1.190 – 2.034) | 0.001 | 1.012 (0.844 – 1.215) | 0.894 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 1.359 (1.066 – 1.733) | 0.013 | 1.427 (1.227 – 1.659) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.246 (1.050 – 1.479) | 0.012 | 0.736 (0.666 – 0.814) | < 0.001 |

| Neurologic Disorders | 0.983 (0.767 – 1.260) | 0.891 | 1.138 (0.988 – 1.312) | 0.074 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease | 1.035 (0.862 – 1.243) | 0.710 | 1.128 (1.012 – 1.257) | 0.029 |

| Diabetes Mellitus with Complications | 0.995 (0.821 – 1.207) | 0.962 | 0.800 (0.706 – 0.907) | < 0.001 |

| Renal Failure | 1.019 (0.838 – 1.239) | 0.852 | 0.956 (0.850 – 1.074) | 0.445 |

| Liver Disease | 1.689 (1.273 – 2.241) | < 0.001 | 1.848 (1.505 – 2.268) | < 0.001 |

| Metastatic Cancer | 2.275 (1.607 – 3.220) | < 0.001 | 2.052 (1.630 – 2.583) | 0.045 |

| Top-Decile Sepsis-Volume Hospital (per 10 miles) | 0.756 (0.722 – 0.793) | < 0.001 | 0.979 (0.960 – 0.999) | 0.045 |

| Rural Hospital Bypass | N/A | N/A | 1.255 (1.027 – 1.535) | 0.027 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval

All numbered references in this table refer to reference numbers from the main manuscript.

Mortality Analysis

Rural patients who presented to their local hospital were more likely to survive their sepsis hospitalization than those who presented initially to a tertiary care center (Table 2). In the instrumental variables model, patients who bypassed their local rural hospital continued to have 5.6% higher mortality than those who initially visited the local emergency department. The instrumental variables model did not adjust the effect of rural hospital bypass significantly from the naïve linear regression model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Instrumental variables model predicting hospital mortality, using an instrument of distance to a top-decile sepsis volume hospital. The naïve model is the linear regression model without using the instrumental variables approach.

| Naïve Model (Ordinary Least Squares) |

Instrumental Variable: 2-Stage Least Squares* (Linear) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | aOR (95%CI) | p | β (95%CI) | p |

| Rural Hospital Bypass | 0.061 (0.032 – 0.090) |

< 0.001 | 0.056 (0.022 – 0.089) |

0.001 |

| Inter-hospital Transfer | 0.097 (0.082 – 0.112) |

< 0.001 | 0.075 (0.005 – 0.144) |

0.034 |

| Age, per decade increase |

0.023 (0.018 – 0.029) |

< 0.001 | 0.022 (0.013 – 0.030) |

< 0.001 |

| Non-White | 0.018 (−0.036 – 0.071) |

0.523 | 0.018 (−0.035 – 0.072) |

0.503 |

| Male | −0.019 (−0.032) – −0.006) |

0.004 | −0.019 (−0.032 – − 0.006) |

0.004 |

| Rural Residence31 | 0.021 (−0.002 – 0.045) |

0.073 | 0.020 (−0.003 – 0.044) |

0.094 |

| Insurance Type | 0.101 | |||

| Medicare | 0.014 (−0.009 – 0.037) |

0.100 | 0.012 (−0.012 – 0.036) |

|

| Medicaid | 0.024 (−0.009 – 0.057) |

0.023 (−0.012 – 0.036) |

||

| Commercial | 0 (ref) | 0 (ref) | ||

| Uninsured | 0.050 (0.008 – 0.091) |

0.051 (0.009 – 0.093) |

||

| Source of Infection28 | ||||

| Pneumonia | −0.044 (−0.059 – −0.029) |

< 0.001 | −0.048 (−0.068 – − 0.028) |

< 0.001 |

| Urinary Tract Infection |

−0.118 (−0.135 – −0.101) |

< 0.001 | −0.123 (−0.144 –− 0.101) |

< 0.001 |

| Cellulitis and Soft Tissue Infection |

−0.110 (−0.136 – −0.084) |

< 0.001 | −0.113 (−0.140 – − 0.085) |

<0.001 |

| Comorbidities (Elixhauser methodology)30 |

||||

| Congestive Heart Failure |

0.032 (0.017 – 0.047) |

< 0.001 | 0.033 (0.018 – 0.049) |

< 0.001 |

| Valvular Heart Disease |

−0.007 (−0.033 – 0.018) |

0.571 | −0.005 (−0.031 – 0.022) |

0.727 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 0.039 (0.017 – 0.061) |

< 0.001 | 0.042 (0.018 – 0.066) |

< 0.001 |

| Hypertension | −0.051 (−0.064 – −0.037) |

< 0.001 | −0.048 (−0.063 – − 0.033) |

< 0.001 |

| Neurologic Disorders | 0.019 (0.001 – 0.038) |

0.045 | 0.019 (−0.001 – 0.038) |

0.052 |

| Chronic Pulmonary Disease |

0.004 (−0.010 – 0.019) |

0.565 | 0.007 (−0.010 – 0.024) |

0.407 |

| Diabetes Mellitus with Complications |

−0.032 (−0.047 – −0.016) |

< 0.001 | −0.031 (−0.47 – −0.015) |

<0.001 |

| Renal Failure | −0.015 (−0.030 – 0.001) |

0.054 | −0.013 (−0.029 – 0.003) |

0.119 |

| Liver Disease | 0.091 (0.060 – 0.123) |

< 0.001 | 0.093 (0.061 – 0.124) |

<0.001 |

| Metastatic Cancer | 0.102 (0.067 – 0.138) |

< 0.001 | 0.105 (0.068 – 0.141) |

< 0.001 |

95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Instrumental variables model F-statistic = 623.5.

All numbered references in this table refer to reference numbers from the main manuscript.

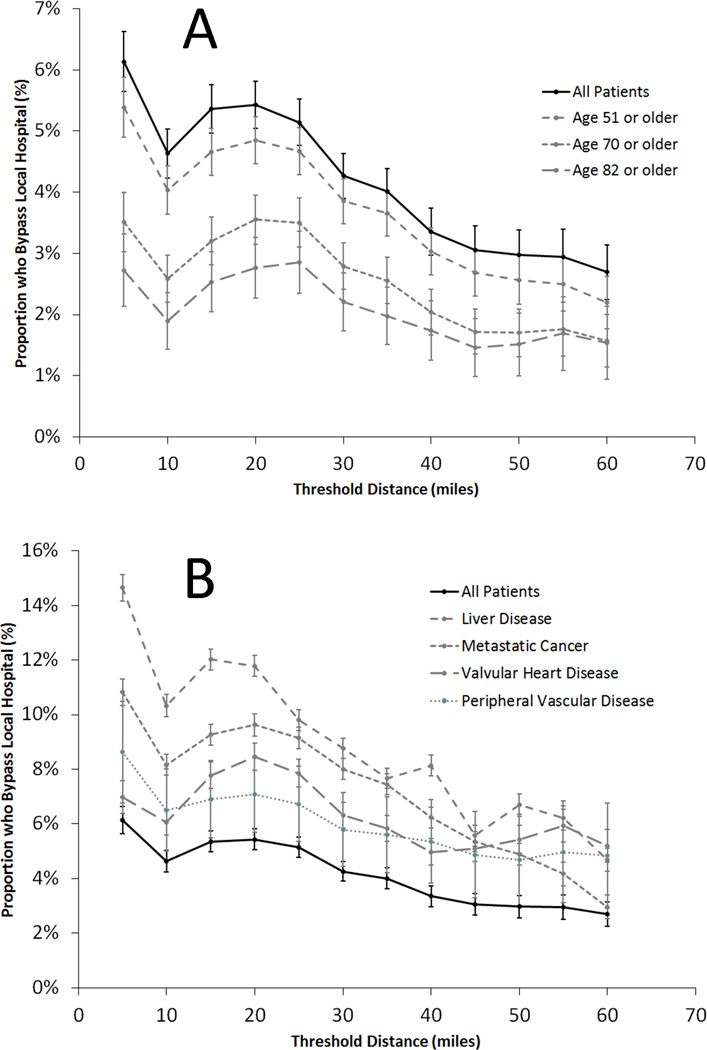

Driving Distance Sensitivity Analysis

As driving distance to a top-decile sepsis volume hospital increases, the proportion of patients who bypass local hospitals falls rapidly, with the greatest proportion of patients willing to bypass local hospitals with a threshold defined at 20 miles. Interestingly, older patients are less likely to bypass rural hospitals, and those with comorbid medical conditions are much more likely (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Rate of rural hospital bypass in severe sepsis or septic shock, stratified by additional travel distance.

A. Older patients are less likely to bypass local rural hospitals than younger patients B. Patients with significant comorbidities were more likely to bypass local rural hospitals.

Inpatient Transfer

Although the transfer rate for sepsis patients who bypassed rural hospitals was lower than those who sought care in rural hospitals (52.1% vs. 60.8%, p<0.001), more of these transferred patients were transferred from inpatient status after hospital admission (65.4% vs. 30.0%, p<0.001). Those transferred from inpatient status had higher mortality than those transferred from the ED (22.8% vs. 18.9%, p<0.001).

Discussion

Multiple studies have detailed how rural patients experience delays or limitations in accessing health care (4, 35), and prior studies have examined the issue of patient choice in rural patients’ receipt of care in rural hospitals.(15, 21–23, 36–39) Much of the data describing rural hospital bypass focuses on elective and scheduled health care (20, 24, 40), rather than unscheduled emergent care. This report is the first to detail issues of patient choice and hospital selection specifically among the critically ill, and it suggests that in this population the rural hospital bypass rate is much lower than the 30–50% rate reported in rural bypass studies previously.(19–25)

Our data identified that 95 percent of rural patients being admitted with severe sepsis or septic shock received care in local hospitals. The majority of these hospitals were critical access hospitals, a federal designation for small hospitals with 24-hour emergency services, but without many of the resources that larger urban hospitals have. From our data, it is not possible to determine whether patients sought local care because (1) it was most rapidly available and they perceived that they had a time-sensitive condition, (2) they were transported by ambulance, and emergency medical personnel selected a local hospital for treatment, (3) they anticipated transfer to a tertiary center because of their perceived severity of illness, or (4) because they preferred to receive care from their personal physician. We have reported previously that rural patients value strongly both proximity to home and the comprehensive medical capabilities of the hospital where they receive their care (9), but balancing these factors with their perceived severity of illness and the capabilities of local hospitals can be challenging.(41)

Despite the low rate of rural hospital bypass, patients who bypassed local hospitals had characteristics that differed from rural hospital patients in very important ways. First, they were more likely to have commercial insurance. This could be because of differences in transportation availability (for which health insurance is functioning as a surrogate measure), because commercial health insurance carriers required participants to travel to preferred hospitals or health systems, or because rural bypass patients are younger and less likely to be qualified for Medicare coverage (unlikely, because these differences persist in those younger than 65). This factor has importance for rural hospital systems, for whom payer mix is critical to maintaining financial viability (42–44), and also for case-mix risk adjustment models, because health insurance has been associated with clinical outcomes.(45, 46)

Second, using a multivariable model to adjust for potential confounders, rural hospital bypass is associated with higher mortality. A mortality difference could have one of two possible explanations: (1) either rural hospital bypass causes worse clinical outcomes because of delays in sepsis care, or (2) the observed differences come from inadequate risk adjustment for the factors that differ between rural bypass and non-bypass patients. The instrumental variables model attempts to adjust for unmeasured differences in severity of illness, and despite the adjustment, mortality is still higher in those who bypass rural hospitals. This finding suggests that the association may be causal, and that timely resuscitation provided in rural hospitals may be better than the delay during which patients are traveling to tertiary centers. Notably, the instrumental variables model is only slightly different from the naïve linear regression model, so although the effect remains significant, the adjustment provided by the instrumental variables approach was small. The 5.6% increased mortality associated with rural hospital bypass approximates the 7.6% per hour increased mortality associated with antibiotic delays previously reported by Kumar, et al.(26) With an average additional distance to first hospital of 51 miles in rural bypass patients, it seems possible that delays in antimicrobial therapy and resuscitation could explain much of the mortality decrement in patients who bypass rural EDs.

Third, the differences in transfer patterns between those who bypass rural hospitals are interesting and may inform our understanding of rural sepsis networks. Those patients who present to rural hospitals are often transferred from the ED to a high-volume tertiary center. Interestingly, though, many who drive to a top-decile sepsis volume hospital are also transferred to a higher volume center. The difference in these groups is that those who bypassed rural hospitals and sought care at larger hospitals were typically admitted to the hospital and were subsequently transferred from inpatient status, while those who presented to rural hospitals were transferred from the ED. That is an important distinction, because even among transferred patients, mortality is 21% higher in those transferred from inpatient status than those transferred from the ED. Presenting to a rural ED and receiving timely sepsis therapy prior to being transferred may be preferable to presenting to a larger hospital that still may ultimately require transfer, but for which the transfer may be delayed for inpatient admission. In this way, commercial insurance may actually be associated with delays in care, similar to that observed in the trauma literature.(47)

So how can these findings be used to improve sepsis care? First, this study is the first to observe how low the rate of rural hospital bypass is among patients with sepsis. This finding is important, because it suggests that rural critical access hospitals are an important consideration in developing rural sepsis networks. Most patients in rural America receive sepsis care in these hospitals, so the need for rural sepsis protocols and rural hospitals’ influence on clinical outcomes cannot be discounted. It also raises important questions on how rural care can be substituted in areas where rural hospitals are closing. Second, although many regionalization systems have been designed to bypass rural hospitals to achieve rapid regionalization for patients with trauma and ST-elevation myocardial infarction (8, 48, 49), these regionalization strategies may be inappropriate for sepsis care. In contrast to conditions where specific interventions are only available in tertiary hospitals, sepsis care can be delivered in rural EDs, and these interventions appear to be important. Finally, these data highlight the importance of accurate risk stratification among patients who are not immediately transferred. Many patients admitted to even a top-decile hospital are ultimately transferred, but they are often admitted to inpatient status first. Those patients admitted as inpatients and subsequently transferred have higher mortality than those transferred immediately, so the ability to accurately identify patients who benefit from tertiary care early may also improve sepsis survival.

This study has several limitations. The administrative data employed for the study is retrospective data and is subject to error in classifying and coding the information. Specifically, part of the increased prevalence of sepsis over this time period is related to improvements in medical coding, and initiatives to improve the coding of major comorbid conditions over this period could have increased the apparent prevalence of these conditions over time. We do not expect, however, that those changes in coding sepsis or comorbid diagnoses introduced bias, because these efforts have been in place nationally over the same period. We are unable to determine why patients chose to bypass their local hospital, and many may have chosen to seek care in a tertiary hospital because of health insurance or prior care for chronic medical conditions. In addition, we do not know the transportation mode used by patients to arrive at their particular hospital. Patients arriving by ambulance may not have participated in destination decision-making, and EMS services may have had pre-selected receiving hospitals within their emergency response area. Although we are using comparative effectiveness techniques to understand how decision-making influences outcomes, our observational design only allows us to identify association, rather than causation. Finally, we used objective covariates as part of the data analysis, but we do not have any data regarding patients’ subjective thoughts and impressions, which may influence not only the hospitals where they choose to seek care, but also the reasons why they choose to be seen in those hospitals.

Conclusion

Rural hospital bypass is rare among those presenting to EDs with severe sepsis or septic shock. Patients who bypass rural EDs are younger, more likely to have commercial insurance, and have more medical comorbidities than those who present to rural hospitals. Distance to a top-decile sepsis volume hospital strongly predicts whether patients will bypass local hospitals to seek care in a larger hospital. Even when adjusting for measured and unmeasured confounders using an instrumental variable model, rural hospital bypass continues to be associated with higher mortality. Future research should better elucidate the role of rural EDs in caring for patients with sepsis, defining prospective criteria for transfer to regional sepsis centers, and providing prehospital providers guidance on centers most appropriate for caring for patients with severe sepsis prospectively.

Supplementary Material

ED, emergency department

Acknowledgments

NMM had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. KKH, DMS, and JCT contributed substantially to the study design, data management and interpretation of findings, critically reviewing the manuscript, and approving the final version. AA, BMF, and MMW each contributed to the interpretation of findings, critically reviewing the manuscript, and approving the final version. The authors would like to acknowledge Zachary Miller, Oluwole Akintayo, MD, Shannon Findlay, MD, Olga Kravchuk, MD, and Andrew Stoltze, MD for their assistance with data collection. The authors would also like to acknowledge Craig Jarvie and Sara Hayes for their help in providing and interpreting the discharge data sets. Funding for this study was provided by the Emergency Medicine Foundation, the University of Iowa Department of Emergency Medicine, and the University of Iowa Institute for Clinical and Translational Sciences, which is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, grant U54TR001356. NMM is also supported by a grant from the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, Health Resources and Services Administration.

Footnotes

Institution Where the Work was Performed: University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa City, Iowa

Conflicts of Interest: No conflicts of interest were declared.

The authors have no financial or nonfinancial conflicts of interest.

Prior Presentations: This study was presented in abstract form at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Annual Meeting in New Orleans, Louisiana on May 12, 2016.

References

- 1.Filbin MR, Arias SA, Camargo CA, Jr, et al. Sepsis visits and antibiotic utilization in U.S. emergency departments*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(3):528–535. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhodes A, Phillips G, Beale R, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundles and outcome: results from the International Multicentre Prevalence Study on Sepsis (the IMPreSS study) Intensive Care Med. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3906-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rivers EP. Point: adherence to early goal-directed therapy: does it really matter? Yes. After a decade, the scientific proof speaks for itself. Chest. 2010;138(3):476–480. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1405. discussion 484–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faine BA, Noack JM, Wong T, et al. Interhospital Transfer Delays Appropriate Treatment for Patients With Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(12):2589–2596. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dellinger RP, Levy M, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(2):165–228. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kocher KE, Haggins AN, Sabbatini AK, et al. Emergency Department Hospitalization Volume and Mortality in the United States. Ann Emerg Med. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohr NM, Harland KK, Shane D, et al. Inter-Hospital Transfer is Associated with Increased Mortality on Severe Sepsis: An Instrumental Variables Approach [oral conference presentation]. American College of Emergency Physicians Research Forum; 26 Oct 2015; Boston, Massachusetts. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feazel L, Schlichting AB, Bell GR, et al. Achieving regionalization through rural interhospital transfer. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1288–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohr N, Wong T, Faine B, et al. Divergence between patient and clinician priorities in rural inter-hospital transfer: A mixed methods study [in press] J Rural Health. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jrh.12125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dranove D, White WD, Wu L. Segmentation in local hospital markets. Med Care. 1993;31(1):52–64. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199301000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phibbs CS, Mark DH, Luft HS, et al. Choice of hospital for delivery: a comparison of high-risk and low-risk women. Health Serv Res. 1993;28(2):201–222. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Exworthy M, Peckham S. Access, Choice and Travel: Implications for Health Policy. Social Policy & Administration. 2006;40(3):267–287. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tai W-TC, Porell FW, Adams EK. Hospital Choice of Rural Medicare Beneficiaries: Patient, Hospital Attributes, and the Patient–Physician Relationship. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(6p1):1903–1922. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00324.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson DA, Yarnold PR, Williams DR, et al. Effects of Actual Waiting Time, Perceived Waiting Time, Information Delivery, and Expressive Quality on Patient Satisfaction in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28(6):657–665. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varkevisser M, Geest SA. Why do patients bypass the nearest hospital? An empirical analysis for orthopaedic care and neurosurgery in the Netherlands. The European Journal of Health Economics. 2007;8(3):287–295. doi: 10.1007/s10198-006-0035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams EK, Houchens R, Wright GE, et al. Predicting hospital choice for rural Medicare beneficiaries: the role of severity of illness. Health Serv Res. 1991;26(5):583–612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettengill J, Vertrees J. Reliability and Validity in Hospital Case-Mix Measurement. Health Care Financ Rev. 1982;4(2):101–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garber AM, Fuchs VR, Silverman JF. Case Mix, Costs, and Outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 1984;310(19):1231–1237. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405103101906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radcliff TA, Brasure M, Moscovice IS, et al. Understanding Rural Hospital Bypass Behavior. The Journal of Rural Health. 2003;19(3):252–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2003.tb00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders SR, Erickson LD, Call VR, et al. Rural health care bypass behavior: how community and spatial characteristics affect primary health care selection. J Rural Health. 2015;31(2):146–156. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders SR, Erickson LD, Call VR, et al. Middle-Aged and Older Adult Health Care Selection: Health Care Bypass Behavior in Rural Communities in Montana. J Appl Gerontol. 2015 doi: 10.1177/0733464815602108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buczko W. Rural Medicare beneficiaries' use of rural and urban hospitals. J Rural Health. 2001;17(1):53–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2001.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basu J, Mobley LR. Illness severity and propensity to travel along the urban-rural continuum. Health Place. 2007;13(2):381–399. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weigel PA, Ullrich F, Finegan CN, et al. Rural Bypass for Elective Surgeries. J Rural Health. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jrh.12163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Escarce JJ, Kapur K. Do patients bypass rural hospitals? Determinants of inpatient hospital choice in rural California. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):625–644. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1589–1596. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chalfin DB, Trzeciak S, Likourezos A, et al. Impact of delayed transfer of critically ill patients from the emergency department to the intensive care unit*. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(6):1477–1483. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266585.74905.5A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mehta HB, Dimou F, Adhikari D, et al. Comparison of Comorbidity Scores in Predicting Surgical Outcomes. Med Care. 2015 doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elixhauser A, Elixhauser A, McCarthy EM. Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. [[cited 2015 June]];Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015 Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp.

- 31.WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. RUCA data. [Accessed November 7, 2012];Code definitions, v. 2.0. [cited Available from: http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/ruca-codes.php. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cromartie J. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. 2014 Jun 2; 2014 [cited 2015 Available from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes.aspx.

- 33.Google Maps APIs. [cited February 2015];2014 Available from: https://developers.google.com/maps/?hl=en. [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bechtold D, Salvatierra GG, Bulley E, et al. Geographic Variation in Treatment and Outcomes Among Patients With AMI: Investigating Urban-Rural Differences Among Hospitalized Patients. J Rural Health. 2015 doi: 10.1111/jrh.12165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Basu J. Severity of illness, race, and choice of local versus distant hospitals among the elderly. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(2):391–405. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Basu J, Mobley LR. Impact of local resources on hospitalization patterns of Medicare beneficiaries and propensity to travel outside local markets. J Rural Health. 2010;26(1):20–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2009.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buczko W. Nonuse of local hospitals by rural Medicare beneficiaries. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 1997;19(3):319–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buczko W. Bypassing of local hospitals by rural Medicare beneficiaries. J Rural Health. 1994;10(4):237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.1994.tb00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bronstein JM, Morrisey MA. Bypassing rural hospitals for obstetrics care. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1991;16(1):87–118. doi: 10.1215/03616878-16-1-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dy SM, Rubin HR, Lehmann HP. Why do patients and families request transfers to tertiary care? a qualitative study. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(8):1846–1853. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langland-Orban B, Gapenski LC, Vogel WB. Differences in characteristics of hospitals with sustained high and sustained low profitability. Hospital & Health Services Administration. 1996;41(3):385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vogel WB, Langland-Orban B, Gapenski LC. Factors influencing high and low profitability among hospitals. Health Care Management Review. 1993;18(2):15–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mullner RM, McNeil D. Rural and urban hospital closures: a comparison. Health Aff (Millwood) 1986;5(3):131–141. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.5.3.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haider AH, Chang DC, Efron DT, et al. Race and insurance status as risk factors for trauma mortality. Arch Surg. 2008;143(10):945–949. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.10.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Durairaj L, Will JG, Torner JC, et al. Prognostic factors for mortality following interhospital transfers to the medical intensive care unit of a tertiary referral center. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(7):1981–1986. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000069730.02769.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Delgado M, Yokell MA, Staudenmayer KL, et al. Factors associated with the disposition of severely injured patients initially seen at non–trauma center emergency departments: Disparities by insurance status. JAMA Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fosbol EL, Granger CB, Jollis JG, et al. The impact of a statewide pre-hospital STEMI strategy to bypass hospitals without percutaneous coronary intervention capability on treatment times. Circulation. 2013;127(5):604–612. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.118463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nathens AB, Jurkovich GJ, Cummings P, et al. The effect of organized systems of trauma care on motor vehicle crash mortality. JAMA. 2000;283(15):1990–1994. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Surgery Flag Software. [cited June 2015];Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2015 Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/surgflags/surgeryflags.jsp.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ED, emergency department