Abstract

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is a strong predictor of suicidal ideation and attempts. Consistent with the interpersonal theory of suicide, preliminary evidence suggests that NSSI is associated with higher levels of perceived burdensomeness (PB) and thwarted belongingness (TB). However, no study to date has examined the cross-sectional and prospective relationships between NSSI, TB, PB, and suicidal ideation (SI). To fill this gap, this study examined the mediating role of TB and PB in the relationship between NSSI and SI at baseline and follow-up. Young adults (N=49) with and without histories of NSSI completed self-report measures of TB, PB, and SI at three time points over two months. NSSI history was associated with higher levels of PB, TB, and SI at all time points. TB and PB significantly accounted for the relationship between NSSI history and SI at baseline. However, the relationship between NSSI history and SI at follow-up was mediated by PB, not TB. Findings provide evidence for the roles of TB and PB in the relationship between NSSI and SI, and partial support for the interpersonal theory of suicide. Future research and clinical implications are discussed.

Keywords: Non-suicidal self-injury, Suicidal ideation, Thwarted belongingness, Perceived burdensomeness, Interpersonal theory of suicide

1. Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), or the intentional destruction of one's own body tissue without the desire to die (Silverman et al., 2007), is increasingly common among young adults in the United States. Researchers estimate that approximately 5.9% of individuals report lifetime NSSI (Klonsky, 2011), with even higher rates of NSSI among older adolescent and young adult populations (12–38%; Gratz et al., 2002; Heath et al., 2008; Jacobson and Gould, 2007; Polk and Liss, 2007; Whitlock et al., 2006). Although there is consistent evidence that NSSI is a robust predictor of suicide-related behaviors and that these behaviors co-occur (Andover and Gibb, 2010; Asarnow et al., 2011; Klonsky et al., 2013; Klonsky and Muehlenkamp, 2007; Muehlenkamp and Gutierrez, 2007; Nock et al., 2006; Wilkinson et al., 2011), not all self-injurers exhibit suicide-related symptoms. In some studies, researchers report that only 34–45% of older adolescents and young adults engaging in NSSI also report suicidal ideation (Hawton, Rodham, Evans, and Weatherall, 2002; Muehlenkamp and Kerr, 2010; Whitlock et al., 2009), and in other studies, the majority of individual engaging in NSSI did not exhibit any suicide-related behaviors (Muehlenkamp and Guiterrez, 2004; Whitlock and Knox, 2007). This suggests that while there is significant overlap, there are also important differences between those who self-harm with and without suicidal intent.

Previous studies seeking to examine the distinction between NSSI and suicide-related behaviors have taken two main approaches. Some have compared individuals who only engage in NSSI to those who only exhibit suicide-related behaviors. These studies have found that compared to individuals with a history of suicide attempts, individuals engaging in NSSI are more interpersonally sensitive and report more stress during interpersonal conflicts (Kim et al., 2015), identify more strongly with death and suicide (Dickstein et al., 2015), and are at greater risk for attempting suicide in the future (Asarnow et al., 2011). Other studies have examined this overlap by comparing individuals who engage in NSSI only to those who have a history of both NSSI and suicide attempts. These studies have found that in adolescent and adult samples, individuals with both NSSI and suicide attempt histories report more severe symptoms of psychopathology than individuals with either of those self-harming behaviors alone (Dougherty et al., 2009; Guertin et al., 2001; Muehlenkamp and Gutierrez, 2007; Stanley et al., 2001). Overall, these findings indicate correlational links between suicidality and NSSI; however, there is a lack of emphasis on the mechanisms underlying this relationship, which limits our ability to understand factors that can predict future suicide-related symptoms among those engaging in NSSI.

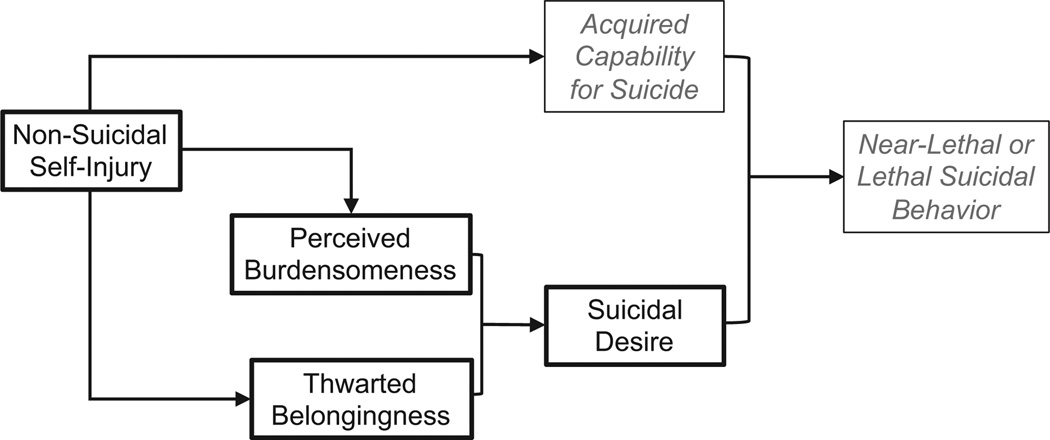

In an effort to better understand these behaviors, theories of suicidal behavior may provide insight. One theoretical approach that may shed light on the overlap between these behaviors is the interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner, 2005; Van Orden et al., 2010). Briefly, the interpersonal theory posits that the combination of perceived burdensomeness (i.e., feeling that others would be better o. without the self) and thwarted belongingness (i.e., social disconnection and loneliness) represents severe suicidal desire. When combined with the acquired capability for suicide (i.e., fearlessness about death and elevated physical pain tolerance), an individual is said to be at risk for engaging in a lethal or near-lethal suicide attempt.

From the lens of the interpersonal theory, the connection between NSSI and suicidal behavior is driven largely by the influence of NSSI on the acquired capability for suicide (Joiner et al., 2012). The interpersonal theory postulates that repeated NSSI engagement decreases fear of death and injury and increases tolerance for pain, thereby elevating capability for suicide and facilitating suicidal behavior. Converging evidence supports these conjectures. For example, previous research has reported that individuals with a history of NSSI show increased pain endurance (Hooley et al., 2010), lower pain ratings, and greater pain thresholds (Schmahl et al., 2004). These findings suggest that NSSI engagement, which repeatedly exposes individuals to a painful and provocative event, may be associated with elevated levels of acquired capability for suicide. Indeed, individuals with a history of NSSI demonstrate higher levels of acquired capability than those without such experiences cross-sectionally (Bender et al., 2011; Franklin et al., 2011; Hooley et al., 2010; Van Orden et al., 2008) and longitudinally, one year later (Willoughby et al., 2015). Overall, these findings appear to support the relationship between acquired capability and NSSI.

Given that the interpersonal theory does not directly delineate a link between NSSI, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, less is known about the relationship between these variables. However, existing evidence suggests that NSSI may negatively impact these interpersonal needs. For one, previous research has suggested that one function of NSSI engagement is to obtain social reinforcement (e.g., to avoid social punishment or show others that they are experiencing negative emotions; Nock and Prinstein, 2004). According to the four-function model of NSSI, those engaging in NSSI for the purposes of social reinforcement may lack interpersonal effectiveness (Nock and Prinstein, 2004). Furthermore, previous research has indicated that individuals with a history of NSSI report poorer social support than individuals without such history (Heath et al., 2009). Thus, NSSI engagement may be related to poorer social functioning, which may increase isolation and feelings of loneliness. Relatedly, researchers have reported that over half of individuals with a history of NSSI report “always” engaging in NSSI alone and one-third of individuals report “sometimes” engaging in NSSI alone (Glenn and Klonsky, 2009). Overtime, poor social support and withdrawal from social interactions may directly contribute to feelings of thwarted belongingness (Van Orden et al., 2010).

A compatible explanation is that the tendency to engage in NSSI alone and reluctance to disclose NSSI may be explained by fears of burdening others. Anecdotally, studies have reported that some individuals engaging in NSSI express concerns that they are placing an emotional burden on friends and family (e.g., burdening parents with feelings of failure, worry, and guilt regarding their parenting skills; Rosenrot, 2015). These feelings may be justified given that research has found that parents of youth who engage in NSSI explicitly report increased burden and stress (Arbuthnott and Lewis, 2015), which may inadvertently reinforce the feelings of burden experienced by those engaging in NSSI. Previous research has suggested that individuals engaging in NSSI may experience shame regarding their behavior (Brown et al., 2009; Gilbert et al., 2010). Shame is associated with concealment of emotional distress and mental illness from others (MacDonald and Morley, 2001). Further, they may also experience fears of social rejection and negative evaluation associated with disclosing self-harm behaviors. In the context of suicide risk, previous evidence has supported the connection between shame, fears of negative social evaluation, and feelings of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (Chu et al., 2015a; Hill and Pettit, 2012; Wong et al., 2014; Van Orden et al., 2010). Thus, one possibility is that some individuals engaging in NSSI fear that they are burdening others.

Research directly testing a potential relationship between NSSI and thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness is limited. In the only empirical test of this hypothesis to date, frequency of NSSI was positively associated with both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness cross-sectionally (Assavedo and Anestis, 2015). However, after controlling for symptoms of depression and borderline personality disorder, only the association between NSSI frequency and thwarted belongingness remained significant and this relationship was fully mediated by these covariates. This suggests that NSSI may be associated with suicidal desire directly through increased feelings of thwarted belongingness and indirectly through perceived burdensomeness. Interestingly, mounting evidence providing partial support for the interpersonal theory of suicide suggests that perceived burdensomeness, individually, may be a more robustly associated with suicidal ideation than thwarted belongingness only or their interaction (Bryan et al., 2012, 2010; Chu et al., 2016; Van Orden et al., 2008). Given these findings, research examining the individual relationships between NSSI and each construct of the interpersonal theory are needed. Additionally, as Assavedo and Anestis's (2015) study employed a cross-sectional approach and did not examine suicide-related behaviors, it is limited in its ability to make conclusions regarding the role of the interpersonal theory of suicide in understanding the ability of NSSI to predict future suicide-related behaviors. Therefore, more studies are needed to replicate and expand these findings to further understand these links.

To our knowledge, no prospective studies have directly examined suicide risk in individuals with a history of NSSI through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. However, findings from previous longitudinal studies examining the association between NSSI and suicide-related behaviors are consistent with the interpersonal theory's hypotheses. For example, Prinstein and colleagues (2008) found that among recently hospitalized adolescents, NSSI history predicted weaker suicidal ideation remission following discharge. Their findings are useful for understanding the interpersonal theory as they are consistent with the idea that repeated engagement in NSSI may habituate adolescents to pain, thereby increasing the likelihood of future suicidal behaviors (Prinstein et al., 2008). However, this study did not assess the interpersonal theory of suicide constructs, and further research is needed to understand the prospective relationship between these variables.

In order to address these gaps in the previous literature on NSSI, this study cross-sectionally and prospectively evaluated the mediating role of the interpersonal theory of suicide variables in the relationship between NSSI on suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Given prevalence of NSSI and suicide-related behaviors among young adults (Barrios et al., 2000; Heath et al., 2008; Whitlock et al., 2009), we examined our research questions in an undergraduate sample. We hypothesized that a) individuals with a history of NSSI would report significantly higher levels of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicidal ideation in comparison to controls; b) thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would significantly mediate the relationship between NSSI and suicidal ideation at baseline; and c) thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness would significantly mediate the relationship between NSSI and suicidal ideation at three- and six-week follow-ups. Fig. 1 summarizes the hypothesized explanatory model for the relationship between NSSI and suicidal behavior from the perspective of the interpersonal theory.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized explanatory model for the association between non-suicidal self-injury and suicide-related behaviors from the perspective of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Constructs denoted in grey were not analyzed in this study.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were 49 young adult undergraduate students (77.6% female), aged 18–23 (M = 18.84, SD = 1.18) at a large Southeastern state university. Approximately one half were recruited due to their history of NSSI. A majority of participants self-identified as White/Caucasian (84%), 16% as Hispanic, 10% as Asian, 4% as Black/African American, and 2.0% as American Indian/Alaskan Native (to ensure cultural sensitivity, participants were allowed to select multiple ethnicities and were not asked to indicate a primary ethnicity). In order to be included in this study, participants had to be proficient in reading and speaking in English and at least 18 years of age. Eleven participants (22%) reported a previous psychiatric diagnosis.

Thirty-three (67.3%) participants reported a lifetime history of NSSI with a lifetime average of 11.02 instances of NSSI (SD = 21.70, range = 1, 100); all individuals with a history of NSSI reported engaging in NSSI in the last year (M = 3.44, SD = 11.51, range = 1, 75). The mean age of onset of NSSI was 13.39 years (SD = 3.13, range = 1, 18) and the average number of years of NSSI was 5.65 years (SD = 3.02, range = 1, 10). The average number of NSSI methods endorsed was 3.18 (SD = 1.88, range = 1, 8) with the majority reporting a history of cutting (78.8%) and wound picking (72.7%). Other methods endorsed included hitting (51.5%), biting (36.4%), scraping skin (30.3%), pulling hair (21.2%), burning (21.2%), and inserting objects under the skin (18.2%). Further, 20 (40%) participants reported lifetime suicidal ideation, 11 (22%) reported having a specific plan, and 7 (14%) reported at least one past suicide attempt. No participants reported a suicide attempt during the study period. See Table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Means (SDs) for Study Variables at Times 1, 2 and 3.

| Variables | Total | Controls | Lifetime NSSI history |

t (df) | Cohen's d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 18.84 (1.18) |

18.56 (1.03) | 18.97 (1.24) |

−1.14 (47) |

−0.33 |

| Gender (% Male) | 22.4 (n=11) |

25.0 (n=4) | 21.2 (n=7) | −0.29 (47) |

−0.08 |

| Number of lifetime NSSI |

– | – | 11.02 (21.70) |

– | – |

| Age of NSSI onset | – | – | 13.39 (3.13) |

– | – |

| % History of suicide attempts |

14.0 (n=7) |

< 0.001 (n=0) | 21.2 (n=7) | −2.03 (47)** |

−0.59 |

| Time 1, N | 49 | 16 | 33 | – | – |

| Suicidal ideation | 0.71 (1.51) |

0.06 (0.25) | 1.03 (1.76) | −2.18 (47)** |

−0.64 |

| Participants endorsing ideation |

n=7 | n=1 | n=6 | – | – |

| Thwarted Belongingness |

24.66 (11.27) |

18.75 (9.17) | 27.49 (11.37) |

−2.68 (47)* |

−0.78 |

| Perceived Burdensome- ness |

10.50 (7.17) |

6.94 (1.44) | 12.27 (8.25) |

−2.56 (47)** |

−0.75 |

| Time 2, N | 42 | 15 | 27 | – | – |

| Suicidal ideation | 0.81 (1.74) |

0.07 (0.26) | 1.22 (2.06) | −2.15 (40)* |

−0.68 |

| Participants endorsing ideation |

n=4 | n=1 | n=3 | – | – |

| Thwarted belongingness |

26.07 (11.62) |

17.93 (9.92) | 29.96 (10.02) |

−3.74 (40)** |

−1.18 |

| Perceived Burdensome- ness |

9.21 (5.78) |

6.93 (1.49) | 10.56 (6.90) |

−2.00 (40)** |

−0.63 |

| NSSI since Time 1 (% Yes) |

7.14 (n=4) |

< 0.001 (n=0) | 11.1 (n=4) | −1.36 (42) |

−0.42 |

| Time 3, N | 42 | 15 | 27 | – | – |

| Suicidal ideation | 0.33 (1.17) |

< 0.001 (0.0) | 0.52 (1.45) | −1.37 (40)** |

−0.43 |

| Participants endorsing ideation |

n=4 | n=0 | n=4 | – | – |

| Thwarted belongingness |

21.95 (11.59) |

18.20 (11.35) | 24.04 (11.61) |

−1.57 (40) |

−0.50 |

| Perceived Burdensome- ness |

9.72 (7.56) |

7.07 (2.09) | 11.33 (9.10) |

−1.78 (40)** |

−0.56 |

| NSSI since Time 2 (% Yes) |

2.0 (n=1) |

< 0.001 (n=0) | 3.7 (n=1) | −0.74 (40) |

−0.23 |

Note Group coded 0=non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) history and 1=controls.

Significance (2-tailed) p < 0.05.

Significance (2-tailed) p < 0.01.

2.2. Procedure

Procedures of this study were approved by the university's Institutional Review Board. All potential participants completed a phone screening to ensure eligibility. Eligible participants completed a series of questionnaires online at three time points: Time 1 (i.e., baseline), Time 2, and Time 3. Due to limited resources, we were unable to collect data from participants after one semester (approximately three months). In order to maximize the amount of data obtained across the semester, assessments were conducted three weeks apart. At each subsequent time point, participants received an email with a link to the follow-up questionnaires, which required them to provide a passcode. At all time points, participants received a full explanation of study procedures and provided informed consent before participating. The following measures were all completed at each time point.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors inventory – short form (SITBI-SF; Nock et al., 2007)

The SITBI-SF is a structured interview that assesses a wide range of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. This study used the self-report version of the SITBI-SF, which was phrased and structured in the same manner as the clinical interview and has been used widely in research (e.g., Zetterqvist et al., 2013). Three domains were assessed in this study: NSSI, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Each domain begins with a general screening question (e.g., “Have you ever had thoughts of non-suicidal self-injury; that is, thoughts of purposely hurting yourself without wanting to die, for example thoughts of cutting or burning?”), with follow-up questions probing for the presence, age of onset, frequency and intensity during lifetime, past year, past month, and past week. As noted by Nock et al. (2007), the SITBI was developed to provide information on a broad range of constructs, and therefore, factor analyses and internal consistency reliability analyses would not be theoretically meaningful. As such, internal consistency was not calculated for the self-report version. Nonetheless, the SITBI has demonstrated strong interrater and test-retest reliability (κ = 0.70–1.0), and the authors provide evidence for construct validity (Nock et al., 2007). In this study, each item was considered individually: questions assessing the frequency and presence of NSSI were used to determine NSSI history and those assessing suicidal ideation and attempts were used to determine ideation and attempt history.

2.3.2. Depressive symptom index – suicidality subscale (DSI-SS; Metalsky and Joiner, 1997)

The DSI-SS is a 4-item self-report measure that assesses the presence and severity of suicidal thoughts, plans, and urges. Each item consists of a group of statements (e.g., “I am not having impulses to kill myself/In some situations I have impulses to kill myself/In most situations I have impulses to kill myself/In all situations I have impulses to kill myself”) ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores reflecting more severe suicidality. Previous research has supported the psychometric properties of this measure (e.g., Joiner et al., 2002; Metalsky and Joiner, 1997). In the current sample, this measure demonstrated adequate to excellent internal consistency across time points 1, 2, and 3 (αs = 0.89, 0.63, 0.95, respectively).

2.3.3. Interpersonal needs questionnaire-15 (INQ; Van Orden et al., 2012)

The INQ is a 15-item self-report measure of perceived burden-someness (6 items, INQ-PB) and thwarted belongingness (9 items, INQ-TB). Responses are rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (Not at all true for me) to 7 (Very true for me); positive items are reverse-coded. Higher scores reffect higher levels of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. Internal consistency ranged from good to excellent across time points 1, 2, and 3 for both the perceived burdensomeness (αs = 0.95, 0.93, 0.98, respectively) and thwarted belongingness (αs = 0.91, 0.84, 0.92, respectively) subscales.

2.3.4. Acquired capability for suicide scale (ACSS; Bender et al., 2011)

The ACSS is a 20-item measure that assesses fearlessness about death and perceived physiological pain tolerance (e.g., “It does not make me nervous when people talk about death”). Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (Not at all like me) to 4 (Very much like me). Higher total scores are indicative of higher levels of acquired capability for suicide. Previous research has provided evidence of the reliability and validity of the ACSS (Bender et al., 2011). Internal consistency in the present study was good at each time-point (αs = 0.85, 0.88, 0.86, respectively).

2.4. Data analytic strategy

SPSS Statistics 23 was used for all analyses. First, we conducted preliminary descriptive and bivariate correlations analyses between all study variables. Independent samples t-tests were used to compare individuals with a history of NSSI to those without such a history on demographic and main study variables. Next, we evaluated the cross-sectional relationship between NSSI history, the interpersonal theory of suicide constructs and suicidal ideation and behavior. The bootstrap technique was used to test for the mediating effects of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (INQ, Time 1) on the relationship between lifetime NSSI history and suicidal ideation (DSI-SS, Time 1). Then, we evaluated the prospective relationship between these variables. Specifically, we examined the mediating effects of thwarted belongingness and perceive burdensomeness (INQ, Time 2) on the relationship between lifetime NSSI history (Time 1) and suicidal ideation (DSI-SS, Time 3). No participants reported a suicide attempt during the study, and therefore, we were unable to examine the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal behavior. Given that previous research has indicated that perceived burdensomeness may be a more robust predictor of suicidal ideation than thwarted belongingness (e.g., Bryan et al., 2010, 2012), in all mediation analyses, we tested perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness as both parallel and individual mediators of the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation.

All mediational analyses were conducted using the PROCESS macro for SPSS 23, following procedures described by Hayes (2013): 10,000 bootstrapped samples were drawn from the data and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (BCCI) were computed in order to estimate the indirect effect for each of the resampled datasets. Previous research has shown age and gender differences in suicidal ideation and behavior (Beautrais, 2001; Van Orden et al., 2010), and therefore, age and gender were included as covariates in all analyses.1 The pattern of findings remained unchanged after accounting of age and gender at all time points.

Missing data were minimal (< 1.0%) at each time point. Analyses were conducted to compare participants with or without complete data on time point 1, 2 and 3. In all cases, no significant effects were revealed on any study variables, which indicates no evidence for biases due to attrition. Missing data analyses indicated that data were missing at random, Little's MCAR χ2(5035) = 1,339.92, ns. Given that list-wise deletion would unnecessarily omit valuable data, all analyses were conducted with all available data. With regard to power, previous research has indicated that a sample size of 53 is required to be adequately powered (0.80) to detect moderate effect sizes for the á path and large effect sizes for the β path using a bias-corrected bootstrap mediation approach (Fritz, 2007). Thus, with our sample size of 49, we were slightly underpowered for analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

Means and standard deviations for all study variables are presented in Table 1, and bivariate correlations are reported in Table 2. As expected, compared to controls, individuals with a history of NSSI were more likely to have a history of at least one suicide attempt and showed significantly higher levels of suicidal ideation and perceived burdensomeness at all three time points. Further, individuals with an NSSI history had significantly higher levels of thwarted belongingness at Time 1 and 2, but not Time 3, in comparison to controls (Table 1). NSSI history was not significantly correlated with acquired capability at any time point.

Table 2.

Correlations between Study Variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. T1 SI | – | ||||||||||

| 2. T1 TB | 0.57** | – | |||||||||

| 3. T1 PB | 0.74** | 0.59** | – | ||||||||

| 4. T1 NSSI | 0.30* | 0.36* | 0.35* | – | |||||||

| 5. T2 SI | 0.60** | 0.37* | 0.56** | 0.32* | – | ||||||

| 6. T2 TB | 0.43* | 0.57** | 0.43* | 0.51* | 0.63** | – | |||||

| 7. T2 PB | 0.64** | 0.57** | 0.89** | 0.30 | 0.58** | 0.44* | – | ||||

| 8. T2 NSSI | −0.04 | 0.04 | 0.001 | 0.07 | −0.13 | −0.05 | 0.10 | – | |||

| 9. T3 SI | 0.40* | 0.42* | 0.61** | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.53** | −0.09 | – | ||

| 10. T3 TB | 0.31* | 0.77** | 0.51* | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.69** | 0.60*** | 0.05 | 0.51* | – | |

| 11. T3 PB | 0.32* | 0.57** | 0.73** | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.42* | 0.78** | 0.06 | 0.81** | 0.71** | – |

| 12. T3 NSSI | −0.07 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.12 | −0.07 | 0.14 | 0.29 | −0.05 | 0.49* | 0.43* | 0.52** |

Note T1=Time 1. T2=Time 2 (3 weeks after T1). T3=Time 3 (3 weeks after T2; 6 weeks after T1). SI=Suicidal Ideation (Depressive Symptom Index-Suicidality Subscale). TB=Thwarted Belongingness (Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-15-Thwarted Belongingness Subscale). PB=Perceived Burdensomeness (Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-15-Perceived Burdensomeness Subscale). AC=Acquired Capability (Acquired Capability Suicide Scale). NSSI=Non-Suicidal Self-Injury (T1=lifetime yes/no, T2=since T1 yes/no, T3= since T2 yes/no).

p < 0.05.

p < 0.001.

We also examined the correlations between thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, acquired capability, and characteristics of NSSI. Findings indicated a significant positive relationship between lifetime NSSI frequency and thwarted belongingness (Time 1: r = 0.33, p = 0.021) and perceived burdensomeness (Time 1: r = 0.41, p = 0.004; Time 3: r = 0.32, p = 0.037); no significant relationship emerged at other time points (p > 0.80). NSSI frequency in the last year was only significantly related to perceived burdensomeness (Time 1: r = 0.40, p = 0.004; Time 2: r = 0.39, p = 0.012; Time 3: r = 0.44, p = 0.004) and not related thwarted belongingness at any time point. There was no significant relationship between years of NSSI, number of NSSI methods, thwarted belongingness, and perceived burdensomeness at any time point. There was no significant relationship between acquired capability (at any time point), and NSSI frequency (lifetime, and in last year), and the number of NSSI methods. There was a significant negative correlation between acquired capability at Time 1 and years of NSSI (r = −0.36, p = 0.046); acquired capability at Time 2 and 3 were not significantly related to years of NSSI.

Independent samples t-tests examining group differences revealed no significant differences in age and gender between individuals with a history of NSSI and controls. Participant age was significantly related to suicidal ideation at Time 1 (r = 0.38, p = 0.008) and at Time 2 (r = 0.34, p = 0.027). Participant gender (coded 1 = female, 2 = male) was significantly associated with acquired capability at Time 1 (r = 0.33, p = 0.018) and Time 2 (r = 0.38, p = 0.012), and suicidal ideation at Time 2 (r = 0.32, p = 0.037).

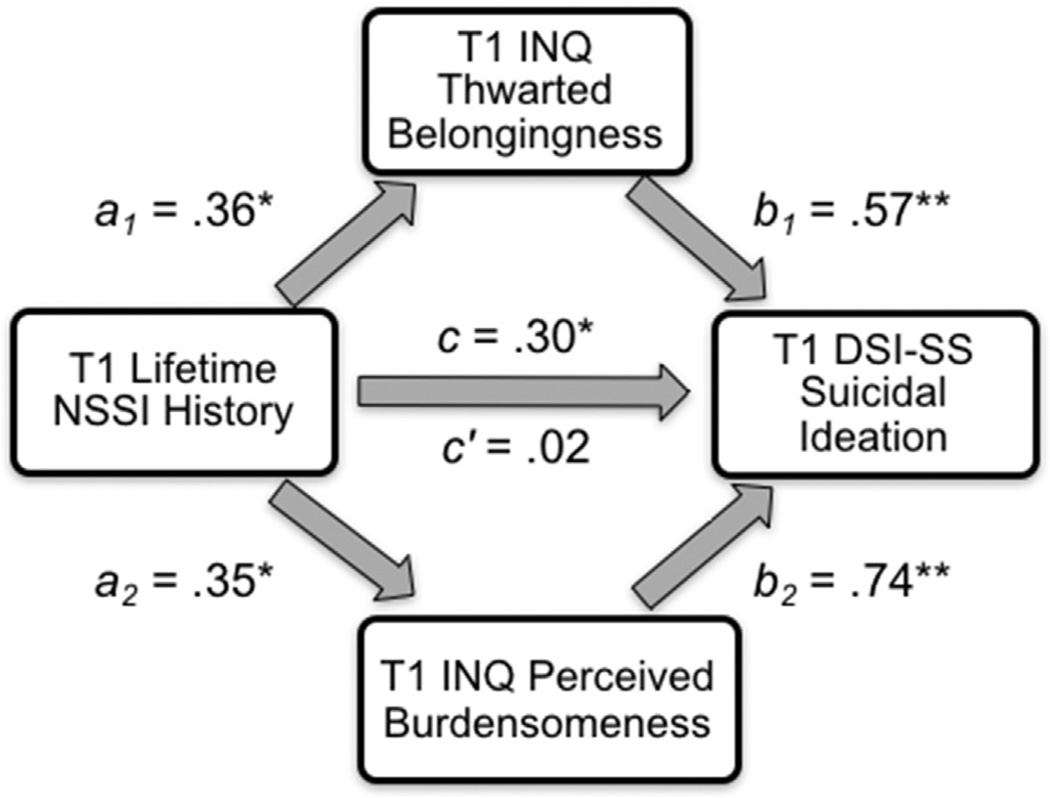

3.2. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as mediators of the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation at Time 1

First, we tested thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as parallel mediators of the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation, controlling for age and gender. The overall regression model explained a significant portion of the variance in suicidal ideation (R2 = 0.63, F[5,43] = 15.54, p < 0.001). NSSI history significantly predicted thwarted belongingness (b = 8.69, SE = 3.38, p = 0.014); however, thwarted belongingness did not significantly predict suicidal ideation (b = 0.03, SE = 0.02, p = 0.09). NSSI history also significantly predicted perceived burdensomeness (b = 5.25, SE = 2.12, p = 0.017), and perceived burdensomeness significantly predicted suicidal ideation (b = 0.12, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001). The direct effect of NSSI history on suicidal ideation was not significant after accounting for the effects of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (b = −0.03, SE = 0.33, p = 0.94), indicating mediation. The indirect effect of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness on the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation was estimated to be between 0.3349 and 1.6374 (95% CI; effect = 0.86, SE = 0.33), indicating significance, as the 95% confidence interval did not cross zero (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation as mediated by thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness cross-sectionally at Time 1. * p≤0.05, ** p≤0.001. T1=Time 1. INQ=Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-15. DSI-SS=Depressive Symptom Index – Suicidality Subscale.

Next, we examined thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as individual mediators of the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation, controlling for age and gender. For analyses examining thwarted belongingness as an individual mediator, the overall regression model explained a significant portion of variance in suicidal ideation (R2 = 0.43, F[4,44] = 8.32, p < 0.001). NSSI history significantly predicted thwarted belongingness (b = 8.69, SE = 3.38, p = 0.014), and thwarted belongingness significantly predicted suicidal ideation (b = 0.07, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001). The direct effect of NSSI history on suicidal ideation was not significant after accounting for the effects of thwarted belongingness (b = 0.27, SE = 0.40, p = 0.51), indicating mediation. The indirect effect of thwarted belongingness on the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation was estimated to be between 0.1261 and 1.3838 (95% CI; effect = 0.57, SE = 0.31), indicating significance.

For analyses examining perceived burdensomeness as an individual mediator, the overall regression model explained a significant portion of variance in suicidal ideation (R2 = 0.60, F[4,44] = 16.67, p < 0.001). NSSI history also significantly predicted perceived burdensomeness (b = 5.25, SE = 2.12, p = 0.017), and perceived burdensomeness significantly predicted suicidal ideation (b = 0.14, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001). The direct effect of NSSI history on suicidal ideation was not significant after accounting for the effects of perceived burdensomeness (b = 0.09, SE = 0.33, p = 0.78), indicating mediation. The indirect effect of perceived burdensomeness on the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation was estimated to be between 0.2658 and 1.5120 (95% CI; effect = 0.74, SE = 0.31), indicating significance.

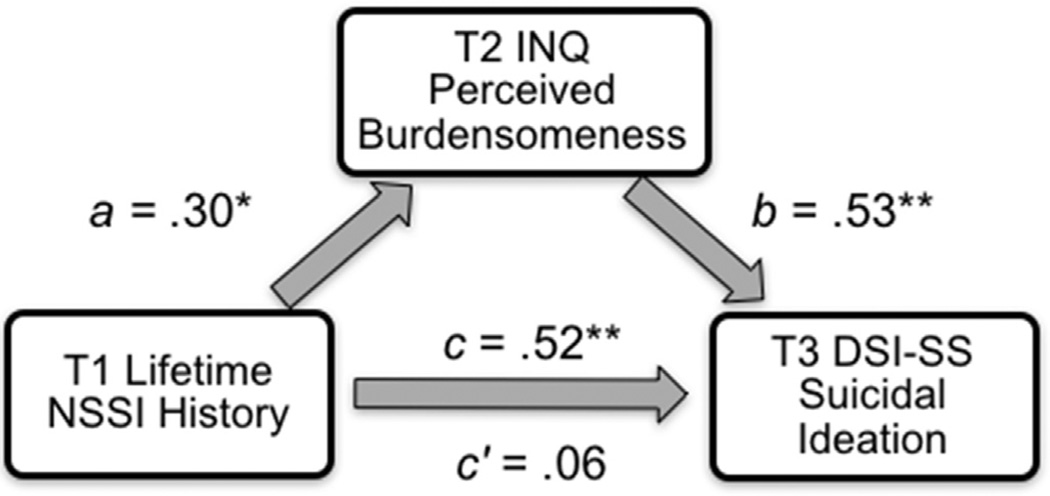

3.3. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as mediators of the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation at follow-up

Finally, we tested thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, both at Time 2, as parallel mediators of the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation at Time 3, controlling for age, gender, and suicidal ideation at Time 1. The overall regression model explained a significant portion of the variance in suicidal ideation at follow-up (R2 = 0.37, F[6,43] = 3.36, p = 0.01. NSSI history significantly predicted thwarted belongingness (b = 11.56, SE = 3.27, p = 0.001), and thwarted belongingness did not significantly predict suicidal ideation at follow-up (b < 0.001, SE = 0.02, p = 0.98). NSSI history significantly predicted perceived burdensomeness (b = 3.66, SE = 1.89, p = 0.016), and perceived burdensomeness significantly predicted suicidal ideation at follow-up (b = 0.11, SE = 0.03, p = 0.003). The direct effect of NSSI history on suicidal ideation at follow-up was not significant after accounting for the effects of the thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (b = −0.05, SE = 0.40, p = 0.91). The indirect effect of NSSI history on suicidal ideation at follow-up via thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness was estimated to be between −0.0006 and 1.4439 (95% CI; effect = 0.39, SE = 0.31) and is not significant as the 95% confidence interval crosses zero.

Again, we examined thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as individual mediators of the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation at follow-up, controlling for age, gender, and suicidal ideation at Time 1. For analyses examining thwarted belongingness as an individual mediator, the overall regression model did not explain a significant portion of variance in suicidal ideation at follow-up (R2 = 0.18, F[5,44] = 1.52, p = 0.21). NSSI history significantly predicted thwarted belongingness (b = 11.56, SE = 3.27, p = 0.001), and thwarted belongingness did not significantly predict suicidal ideation at follow-up (b = 0.03, SE = 0.02, p = 0.20). The direct effect of NSSI history on suicidal ideation was not significant after accounting for the effects of thwarted belongingness (b = 0.04, SE = 0.45, p = 0.93). The indirect effect of thwarted belongingness on the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation at follow-up was estimated to be between −0.0338 and 1.4496 (95% CI; effect = 0.31, SE = 0.26) and is not significant.

Lastly, for analyses examining perceived burdensomeness as an individual mediator, the overall regression model explained a significant portion of variance in suicidal ideation (R2 = 0.37, F[5,44] = 4.16, p = 0.005). NSSI history also significantly predicted perceived burdensomeness (b = 3.66, SE = 1.89, p = 0.0016), and perceived burdensomeness significantly predicted suicidal ideation (b = 0.11, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001). The direct effect of NSSI history on suicidal ideation was not significant after accounting for the effects of perceived burdensomeness (b = −0.05, SE = 0.36, p = 0.89), indicating mediation. The indirect effect of perceived burdensomeness on the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation at follow-up was estimated to be between 0.008 and 1.2607 (95% CI; effect = 0.40, SE = 0.27), indicating significance (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Standardized regression coefficients for the relationship between NSSI history (Time 1) and suicidal ideation (Time 3) as mediated by perceived burdensomeness (Time 2). * p≤0.05, ** p≤0.001. T1=Time 1. T2=Time 2. T3=Time 3. INQ=Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire-15. DSI-SS=Depressive Symptom Index – Suicidality Subscale.

4. Discussion

Despite the overlap between NSSI and suicidal ideation, few studies have examined the mechanisms underlying this relationship from the theoretical framework of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Using both cross-sectional and longitudinal approaches, this study examined the relationship between NSSI history, the two interpersonal theory constructs of suicidal desire, and suicidal ideation across three time points. Results indicated NSSI history was associated with higher levels of thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness, and suicidal ideation at all time points. Further, the cross-sectional relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation was mediated by perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness; however, prospectively, this relationship was only mediated by perceived burdensomeness and not thwarted belongingness.

Consistent with hypotheses and recent findings (Assavedo and Anestis, 2015), we found that individuals with a history of NSSI may consistently lack meaningful social connections with others and feel that they are a burden on others. Notably, our results extend previous findings and suggest that at Time 1, the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation was accounted for by feelings of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. This finding is consistent with the predictions of the interpersonal theory of suicide (Van Orden et al., 2010). However, only perceived burdensomeness and not thwarted belongingness accounted for the relationship between NSSI history and suicidal ideation at follow-up. This suggests that while high levels of thwarted belongingness are correlated with NSSI and suicide-related behaviors, symptoms of perceived burdensomeness among individuals engaging in NSSI may be a more significant predictor of long-term suicide risk. This finding is also in line with mounting evidence that perceived burdensomeness may be a more robust predictor of ideation than thwarted belongingness (Bryan et al., 2012, 2010; Chu et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2016; Van Orden et al., 2008) and provides partial support for the interpersonal theory of suicide.

To our knowledge, only one study has examined the relationship between perceived burdensomeness and NSSI and they found that this relationship was in part accounted for by psychopathology (Assavedo and Anestis, 2015). As discussed previously, an alternative possibility is that the connection between NSSI and perceived burdensomeness is accounted for by feelings of shame regarding NSSI behavior. Although NSSI does not typically inhibit performance in daily activities, which often precipitates feelings of burden, NSSI may also contribute to feelings that one is an emotional burden on close others or a source of worry and guilt (Rosenrot, 2015). However, outside of Assavedo and Anestis’ (2015) findings, little is known about the mechanisms underlying this relationship. The results from this study point to a need for more empirical research on the relationship between NSSI and perceived burdensomeness, and, in particular, studies examining other possible mediating factors may be informative regarding the nature of this relationship.

Interestingly, acquired capability was not significantly related to NSSI history. Given that the interpersonal theory indicates that capability may be developed through repeated exposure to painful and provocative stimuli, one explanation for these nonsignificant findings may be the low severity of NSSI in this sample (lifetime NSSI frequency = 11, average number of NSSI methods = 3). Previous research in clinical and diverse community samples have indicated that the severity of NSSI, including the number of years and methods of NSSI, moderates the relationship between NSSI and suicidal behavior (Nock et al., 2006; Turner et al., 2013). Further, we found a significant negative relationship between acquired capability at Time 1 and years of NSSI in the present sample. One possibility is that in this sample, other factors not assessed in this study (e.g., other painful and provocative events) were contributing to increased acquired capability. Findings may have also been impacted by the unexpectedly higher mean levels of acquired capability in the control sample at all time points. Although these levels of acquired capability were consistent with some research in undergraduate student samples (Holaday and Brausch, 2015), the inclusion of a measure assessing history of experience with painful and provocative events will be informative in future studies.

This study was the first to examine the relationship between NSSI history, the interpersonal theory variables, and suicide-related behaviors. A strength of this study was its cross-sectional and repeated-measures, prospective study design. However, several limitations should be noted. First, this study was limited in its sample size and power. Therefore, caution is warranted when interpreting study results. Relatedly, severity of NSSI and suicidal ideation was low in our sample and few participants endorsed new incidents of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors during the study period. Although a significant number of young adults engage in self-harming behaviors (Whitlock et al., 2009), research replicating these findings using larger samples across diverse settings with more severe NSSI and suicide-related symptoms, such as psychiatric outpatients or inpatients, would be beneficial. Our study was also limited by the use of self-report assessments at all time points. Future studies may be strengthened by employing multiple methods of measurement, including objective measures and self-report. Further, no participants in this study endorsed a suicide attempt after baseline assessment, which limits our ability to draw conclusions about factors predicting suicidal behaviors. Studies with a longer duration between follow-up sessions and an extended study period will yield more data on self-injurious behaviors, which will help to clarify the relationship between the interpersonal theory variables and NSSI.

Lastly, the measure of suicidal ideation evidenced lower internal consistency at Time 2 (DSI-SS α=0.63). Item-level analyses of this measure at Time 2 revealed relatively rare endorsement of all items except item 1, which assesses ideation. One explanation is that item 1 may be interpreted as assessing any lifetime experience with thoughts of suicide (e.g., 0=I do not have thoughts about suicide; 1=Sometimes I have thoughts about suicide; 2=Most of the time…), which may lead to increased endorsement of this item. In contrast, the wording of items 2–4 on the DSI-SS is in the present tense (i.e., “I am having thoughts of suicide…”) and may be more capable of distinguishing participants with current suicidal ideation. Nonetheless, given that no other inconsistences were noted in the DSI-SS and other measures at Time 2 or other time points, the reason for the discrepancy is unclear. Although suicidal ideation at Time 2 was not utilized in the present analyses, the inclusion of other measures of suicidal ideation may help to clarify this finding.

These results, should they be replicated in future research, have important clinical implications for the treatment and prevention of suicide in the young adult population, a population with significant risk for suicide (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012). For one, our findings suggest that NSSI is an important risk factor for suicidal ideation and further, that this relationship may be accounted for, in part, by increased feelings of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. As such, clinicians treating young adults engaging in NSSI should regularly assess suicide risk as the presence of any history of self-injurious behavior is notable (Chu et al., 2015b; Joiner et al., 1999). Among young adults presenting with NSSI and suicidal ideation, clinicians should regularly probe for feelings of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. If present, clinicians may also consider treatments that target distorted cognitions about interpersonal belongingness and burdensomeness, such as cognitive-behavioral approaches (Stellrecht et al., 2006).

Overall, our findings provided partial support for the interpersonal theory of suicide. We found that NSSI history was associated with higher levels of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness and suicidal ideation across time, and that this effect was, cross-sectionally, driven by feelings of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness and, prospectively, by perceived burdensomeness. This was the first study, to our knowledge, to provide information on the mediating role of the interpersonal theory constructs in the relationship between NSSI and suicidal ideation. The present findings provide valuable information about predictors of suicide risk and highlight important differences between those who engage in NSSI and those who do not. Nonetheless, replication and extension of these findings will be necessary for furthering our understanding the role of NSSI in suicide risk assessment and prevention efforts to ultimately reduce rates self-injurious behaviors.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32 MH093311-04). This work was in part supported by the Military Suicide Research Consortium (MSRC), an effort supported by the Department of Defense (W81XWH-10-2-0181). Opinions, interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the authors and are not necessarily endorsed by the MSRC or the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Of note, NSSI history and depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory-II) were significantly and positively correlated at Times 1, 2, and 3 (r = 0.65, 0.43, 0.45, respectively). However, recent research finds that when variance from depressive symptoms is removed from suicidal ideation, what results is only one component of suicidal ideation (i.e., will; see Rogers et al., 2016), when what we were interested in was the entirety of suicidal ideation (depressive cognitions and will). Thus, the depressive symptoms variable was not entered as a covariate.

References

- Andover MS, Gibb BE. Non-suicidal self-injury, attempted suicide, and suicidal intent among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr. Res. 2010;178:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuthnott AE, Lewis SP. Parents of youth who self-injure: a review of the literature and implications for mental health professionals. Child Adol. Psychiatr. Ment. Health. 2015;9:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s13034-015-0066-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asarnow JR, Porta G, Spirito A, Emslie G, Clarke G, Wagner KD, et al. Suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents: findings from the TORDIA study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adol. Psychiatr. 2011;50:772–781. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assavedo BL, Anestis MD. The relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and both perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2015:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios LC, Everett SA, Simon TR, Brener ND. Suicide ideation among US college students associations with other injury risk behaviors. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2000;48(5):229–233. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beautrais A. Suicides and serious suicide attempts: two populations or one? Psychol. Med. 2001;31:837–845. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender TW, Gordon KH, Bresin K, Joiner TE. Impulsivity and suicidality: the mediating role of painful and provocative experiences. J. Aect. Disord. 2011;129:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MZ, Linehan MM, Comtois KA, Murray A, Chapman AL. Shame as a prospective predictor of self-inflicted injury in borderline personality disorder: a multi-modal analysis. Behav. Res. Ther. 2009;47:815–822. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Clemans TA, Hernandez AM. Perceived burdensomeness, fearlessness of death, and suicidality among deployed military personnel. Pers. Indiv. Dif. 2012;52:374–379. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Morrow CE, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. A preliminary test of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior in a military sample. Pers. Indiv. Dif. 2010;48:347–350. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Sep 25, Suicide: Facts at a Glance. Retrieved from: 〈 http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pub/suicide_datasheet.html〉. [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Hom MA, Stanley IH, Joiner TE. A test of the interpersonal theory of suicide in a large sample of current firefighters. Psychiatr. Res. 2016;240:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.03.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Moberg FB, Joiner TE. Thwarted belongingness mediates the relationship between fear of negative evaluation and suicidal ideation. Cog. Ther. Res. 2015a;40:31–37. doi: 10.1007/s10608-015-9715-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Klein KM, Buchman-Schmitt JM, Hom MA, Hagan CR, Joiner TE. Routinized assessment of suicide risk in clinical practice: an empirically informed update. J. Clin. Psychiatr. 2015b;71:1186–1200. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickstein DP, Puzia ME, Cushman GK, Weissman AB, Wegbreit E, Kim KL, Spirito A. Self-injurious implicit attitudes among adolescent suicide attempters versus those engaged in nonsuicidal self-injury. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry. 2015;56:1127–1136. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty DM, Mathias CW, Marsh-Richard DM, Prevette KN, Dawes MA, Hatzis ES, Nouvion SO. Impulsivity and clinical symptoms among adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury with or without attempted suicide. Psychiatry Res. 2009;169:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JC, Hessel ET, Prinstein MJ. Clarifying the role of pain tolerance in suicidal capability. Psychiatr. Res. 2011;189:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol. Sci. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P, McEwan K, Irons C, Bhundia R, Christie R, Broomhead C, et al. Self-harm in a mixed clinical population: the roles of self-criticism, shame, and social rank. Brit. J. Clin. Psych. 2010;49:563–576. doi: 10.1348/014466509X479771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Conrad SD, Roemer L. Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. Am. J. Orthopsychiat. 2002;72(1):128–140. doi: 10.1037//0002-9432.72.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawton K, Rodham K, Evans E, Weatherall R. Deliberate self harm in adolescents: self report survey in schools in England. BMJ. 2002;325:1207–1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7374.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-based Approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heath N, Toste J, Nedecheva T, Charlebois A. An examination of nonsuicidal self-injury among college students. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2008;30:137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Heath NL, Ross S, Toste JR, Charlebois A, Nedecheva T. Retrospective analysis of social factors and nonsuicidal self-injury among young adults. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2009;41:180–186. [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, Pettit JW. Suicidal ideation and sexual orientation in college students: the roles of perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and perceived rejection due to sexual orientation. Suic. Life-Threat. 2012;42:567–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holaday TC, Brausch AM. Suicidal imagery, history of suicidality, and acquired capability in young adults. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 2015;7:127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Ho DT, Slater J, Lockshin A. Pain perception and nonsuicidal self-injury: A laboratory investigation. Pers. Disord. 2010;1(3):170–179. doi: 10.1037/a0020106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson CM, Gould M. The epidemiology and phenomenology of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior among adolescents: A critical review of the literature. Arch. Suicide Res. 2007;11(2):129–147. doi: 10.1080/13811110701247602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why People Die By Suicide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Pfaff JJ, Acres JG. A brief screening tool for suicidal symptoms in adolescents and young adults in general health settings: Reliability and validity data from the Australian National General Practice Youth Suicide Prevention Project. Behav. Res. Ther. 2002;40:471–481. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Ribeiro JD, Silva C. Nonsuicidal self-injury, suicidal behavior, and their co-occurrence as viewed through the lens of the interpersonal theory of suicide. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012;21:342–347. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Walker RL, Rudd DM, Jobes DA. Scientizing and routinizing the assessment of suicidality in outpatient practice. Prof. Psychol.-Res Pr. 1999;30:447–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kim KL, Cushman GK, Weissman AB, Puzia ME, Wegbreit E, Tone EB, Dickstein DP. Behavioral and emotional responses to interpersonal stress: A comparison of adolescents engaged in non-suicidal self-injury to adolescent suicide attempters. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228:899–906. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED. Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychol. Med. 2011;41:1981–1986. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, Muehlenkamp JJ. Self-injury: A research review for the practitioner. J. Clin. Psych. 2007;63:1045–1056. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klonsky ED, May AM, Glenn CR. The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and attempted suicide: converging evidence from four samples. J. Abnorm. Psych. 2013;122:231–237. doi: 10.1037/a0030278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Batterham PJ, Calear AL, Han J. A systematic review of the predictions of the Interpersonal–Psychological Theory of Suicidal Behavior. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016;46:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald J, Morley I. Shame and non-disclosure: a study of the emotional isolation of people referred for psychotherapy. Brit. J. Med. Psych. 2001;74:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metalsky GI, Joiner TE., Jr The hopelessness depression symptom questionnaire. Cog. Ther. Res. 1997;21:359–384. [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Gutierrez PM. An investigation of differences between self-injurious behavior and suicide attempts in a sample of adolescents. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2004;34(1):12–23. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.1.12.27769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Gutierrez PM. Risk for suicide attempts among adolescents who engage in non-suicidal self-injury. Arch. Suic. Res. 2007;11:69–82. doi: 10.1080/13811110600992902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp JJ, Kerr PL. Untangling a complex web: How non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts differ. Prev. Res. 2010;17:8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J. Consult. Clin. Psych. 2004;72(5):885–890. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, Michel BD. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview: development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychol. Assess. 2007;19:309–317. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatr. Res. 2006;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polk E, Liss M. Psychological characteristics of self-injurious behavior. Person. Indiv. Differ. 2007;43(3):567–577. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Nock MK, Simon V, Aikins JW, Cheah CSL, Spirito A. Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts following inpatient hospitalization. J. Consult. Clin. Psych. 2008;76:92–103. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers ML, Stanley IH, Hom MA, Chiurliza B, Podlogar MC, Joiner TE. Conceptual and empirical scrutiny of covarying depression out of suicidal ideation. Assessment. 2016 doi: 10.1177/1073191116645907. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1073191116645907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenrot S. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation. Ontario, Canada: University of Guelph; 2015. Talking About Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Identification of Barriers, Correlates, and Responses to NSSI Disclosure. [Google Scholar]

- Schmahl C, Greffrath W, Baumgartner U, Schlereth T, Magerl W, Philipsen A, et al. Differential nociceptive deficits in patients with borderline personality disorder and self-injurious behavior: laser-evoked potentials, spatial discrimination of noxious stimuli and pain ratings. Pain. 2004;11:470–479. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman MM, Berman AL, Sanddal ND, O’Carroll PW, Joiner TE. Rebuilding the tower of Babel: a revised nomenclature for the study of suicide and suicidal behaviors. Part 2: suicide-related ideations. Commun Behav. Suic. Life-Threat. 2007;37:264–277. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.3.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley B, Gameroff MJ, Michalsen V, Mann JJ. Are suicide attempters who self-mutilate a unique population? Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158(3):427–432. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellrecht NE, Gordon KH, Van Orden K, Witte TK, Wingate LR, Cukrowicz KC, et al. Clinical applications of the interpersonal-psychological theory of attempted and completed suicide. J. Clin. Psychiatr. 2006;62:211–222. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Layden BK, Butler SM, Chapman AL. How often, or how many ways: clarifying the relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality. Arch. Suic. Res. 2013;17:397–415. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.802660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Cukrowicz KC, Witte TK, Joiner TE., Jr Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: construct validity and psychometric properties of the interpersonal needs questionnaire. Psychol. Assess. 2012;24:197–215. doi: 10.1037/a0025358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, James LM, Castro Y, Gordon KH, Braithwaite SR, et al. Suicidal ideation in college students varies across semesters: the mediating role of belongingness. Suic. Life-Threat. 2008;38:427–435. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010;117:575–600. doi: 10.1037/a0018697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Eckenrode J, Silverman D. Self-injurious behaviors in a college population. Pediatric. 2006;117:1939–1948. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Eells G, Cummings N, Purrington A. Nonsuicidal self-injury in college populations: mental health provider assessment of prevalence and need. J. Coll. Stud. Psychother. 2009;23:172–183. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock J, Knox KL. The relationship between self-injurious behavior and suicide in a young adult population. Arch. pediat. adol. Med. 2007;161(7):634–640. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P, Kelvin R, Roberts C, Dubicka B, Goodyer I. Clinical and psychosocial predictors of suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in the Adolescent Depression Antidepressants and Psychotherapy Trial (ADAPT) Am. J. Psychiatr. 2011;168:495–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby T, Heffer T, Hamza CA. The link between nonsuicidal self-injury and acquired capability for suicide: a longitudinal study. J. Abnorm. Psych. 2015;124:1110–1115. doi: 10.1037/abn0000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, Kim BS, Nguyen CP, Cheng JKY, Saw A. The interpersonal shame inventory for Asian Americans: scale development and psychometric properties. J. Couns. Psych. 2014;61:119. doi: 10.1037/a0034681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetterqvist M, Lundh LG, Dahlström Ö, Svedin CG. Prevalence and function of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a community sample of adolescents, using suggested DSM-5 criteria for a potential NSSI disorder. J. Abnorm. Child. Psychiatr. 2013;41(5):759–773. doi: 10.1007/s10802-013-9712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]