Abstract

Five naturally-occurring β-lactams have inspired a class of drugs that constitute >60% of the antimicrobials used in human medicine. Their biosynthetic pathways reveal highly individualized synthetic strategies that yet converge on a common azetidinone ring assembled in structural contexts that confer selective binding and inhibition of D,D-transpeptidases that play essential roles in bacterial cell wall (peptidoglycan) biosynthesis. These enzymes belong to a single “clan” of evolutionarily distinct serine hydrolases whose active site geometry and mechanism of action is specifically matched by these antibiotics for inactivation that is kinetically competitive with their native function. Unusual enzyme-mediated reactions and catalytic multitasking in these pathways are discussed with particular attention to the diverse ways the β-lactam itself is generated, and more broadly how the intrinsic reactivity of this core structural element is modulated in natural systems through the introduction of ring strain and electronic effects.

Introduction

All serine hydrolases can be grouped into “clans,” each descended from a single evolutionary ancestor [1]. Constraints of mechanism and active site geometry have governed the convergent evolution of these enzymes,[2] but it is testament to their power to have independently appeared at least 13 times. The penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), D,D-transpeptidases, catalyze the classical 4–3 crosslinking of muramyl peptide stems during the final stages of bacterial cell wall (peptidoglycan) biosynthesis [3]. The PBPs are members of a single clan of serine hydrolases against which the β-lactam antibiotics have specifically developed and bear the mark of corresponding constraints to their structure and absolute stereochemistry. Remarkably, there are five distinct families of these natural PBP inhibitors known whose independent biosynthetic pathways display both mechanistic virtuosity and synthetic efficiency. This review will focus on the strikingly different solutions in Nature to achieve the thermodynamically uphill synthesis of the azetidinone ring, which is critical for expression of their antibiotic activity.

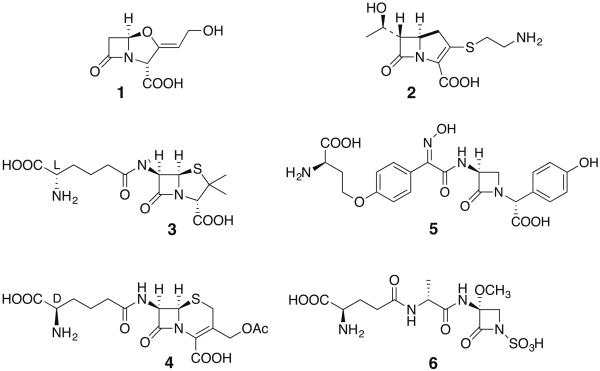

A recent survey of the biosynthetic capacity of more than 800 actinobacterial genomes revealed the predominance of modular polyketide synthases and non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) [4]. Indeed, although three of the five families of β-lactam antibiotics rely on NRPS systems to initiate their biosynthesis, two classes do not: the clavams, notably the clinically-important β-lactamase inhibitor clavulanic acid (1) and the potent, broad-spectrum carbapenems represented here by their progenitor natural product thienamycin (2). Of the former, penicillin and cephalosporin [e.g. isopenicillin N (3) and cephalosporin C (4)] constitute a third class, nocardicin A (5) exemplifies the monocyclic β-lactams, and sulfazecin (6) the related monobactams.

β-Lactam Synthetases, Clavams and Carbapenems

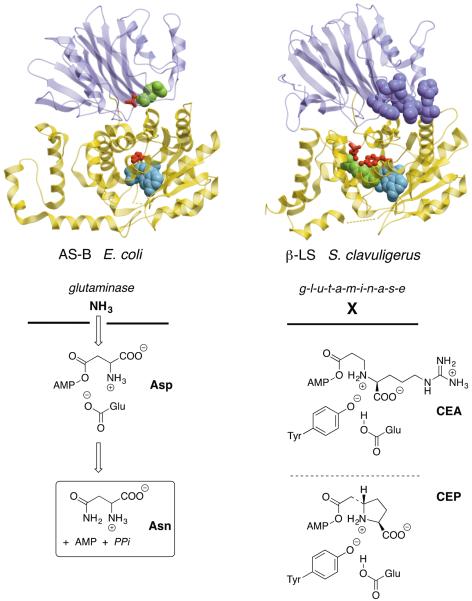

Both clavulanic acid and the carbapenems form their β-lactam rings similarly by ATP-dependent adenylation of a β-amino acid substrate and intramolecular acyl substitution mediated by β-lactam synthetase (β-LS)[5,6] or carbapenam synthetase (CPS),[7] respectively. Interestingly, while β-LS and CPC share only 23% sequence identity, they are each more closely related to their ancestral asparagine synthetases, Class B (AS-B, ~65% identical) than to each other. The latter are highly conserved across the phylogenetic tree of life and, as revealed in the X-ray crystal structure of the E. coli enzyme, the smaller top domain houses a glutaminase whose N-terminal cysteine catalyzes the release of ammonia, which travels through a relatively hydrophobic 19Å tunnel into the larger synthetase domain that binds ATP and activates Asp for intermolecular acyl substitution and the synthesis of Asn (Figure 2A) [8]. Where the ammonia meets the synthetase active site, a Glu residue can be likened to a catcher's mitt to both electrostatically attract the incoming ammonia (ammonium) and possibly deprotonate it if needed to catalyze nucleophilic substitution [9]. It is instructive to compare how the active site has changed in β-LS to accommodate its new role in β-lactam synthesis. The enzyme has lost the ability to convert Asp to Asn. Although the N-terminal glutaminase domain remains, it is notably less structured and the N-terminal cysteine has been replaced by Phe and 9 additional residues have been added to the N-terminus that block the Gln binding pocket and the interdomain tunnel, which no longer exists. The now isolated synthetase domain has enlarged its active site to accommodate and bind the guanidino arm of its carboxyethyl-L-arginine (7, CEA) substrate. A catalytic dyad composed of Tyr and Glu has appeared in the Streptomyces enzyme where the former replaces the Glu, which is strictly conserved in the AS-B superfamily, to mediate the intramolecular attack of the substrate secondary amine to give β-lactam formation [10]. This dyad exhibits a not widely known behavior seen elsewhere in acid–base reactions of “reverse protonation” to present a phenolate anion adroitly matched to the pKa of the substrate secondary ammonium ion. In addition to a series of five crystallographic “snapshots” of the β-LS catalytic cycle,[11] the kinetic mechanism of this key biosynthetic step has been examined in intimate detail for both β-LS and CPS. The latter analyses show that despite distinct remodeling of the active sites, both share a Tyr–Glu catalytic dyad and in their kinetic behavior is more similar than different [12].

Figure 2.

Left, asparagine synthetase, class B from E. coli. Its crystal structure [8] is shown and the reaction catalyzed is depicted beneath. Glutaminase domain (upper) is in purple with Gln bound (green CPK). The N-terminal catalytic Cys is replaced with Ala (red ball-and-stick). The synthetase domain (lower) in yellow has AMP bound (light blue CPK) and the conserved active site Glu is shown (red ball-and-stick). Right, β-lactam synthetase from S. clavuligerus. Its x-ray structure is shown and reaction catalyzed in clavulanic acid (1) biosynthesis is placed directly beneath. The corresponding carbapenam synthetase (CPS) reaction active in carbapenem-3-carboxylate (14) biosynthesis is drawn just below that. The non-functional glutaminase domain (upper) in purple with the Phe and nine additional N-terminal residues shown (purple CPK). The isolated synthetase domain (lower) in yellow has carboxyethyl-L-arginine (CEA) (green CPK) and AMP–CPP (light blue CPK) bound in the active site with the Tyr•Glu catalytic dyad highlighted (red ball-and-stick).

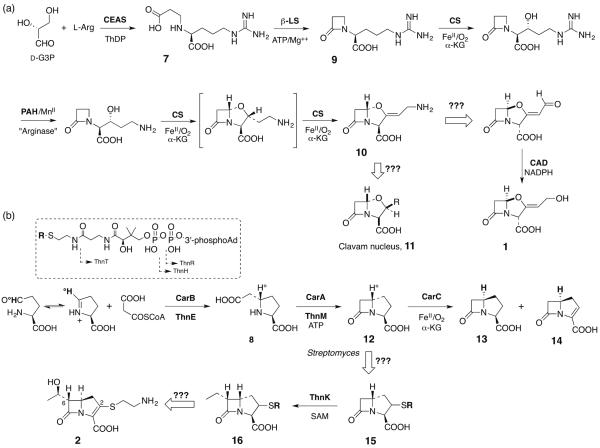

As noted above, sequence comparisons of β-LS and CPS to their bacterial AS-B antecedents clearly suggest separate evolution despite highly similar functional solutions to β-lactam ring formation. Although the clavulanic acid and thienamycin biosynthetic pathways have not been completely elucidated, enough is presently known to confidently state that their stepwise progression relies on markedly different chemistries and that they evolved independently. To illustrate these differences, the formation of CEA (7) captures unprecedented C-N bond formation in thiamin diphosphate (ThDP) catalysis from the primary metabolic building blocks glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P) and L-arginine [13–15] In contrast, three separately precedented crotonase superfamily enzyme reactions are compressed into the formation of (2S,5R)-carboxyethylproline (8) to initiate carbapenem biosynthesis [16,17]. Although detailed discussion of these pathways is outside the scope of this review, the principal steps are sketched out in Figure 3A. Beyond formation of the monocyclic β-lactam in deoxyguanidinoproclavaminic acid (9, DGPC), the oxidation state and inherent strain of the intermediates is steadily elevated in the safely non-antibiotic bridgehead (5S)-configuration. The synthetically versatile clavaminate synthase, a non-heme iron, α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)-dependent oxygenase, carries out three different oxidative transformations (hydroxylation, oxidative cyclization and desaturation) interrupted by an arginase-like step to remove the guanidine group to arrive at clavaminic acid (10). This branch point intermediate is directed in S. clavuligerus and a few allied Streptomycetes to a family of clavam metabolites represented generically by 11 of unchanged bridgehead stereochemistry, or through oxidative deamination [18] coupled in an unknown manner to ring inversion whose now biologically active configuration is trapped by reduction to clavulanic acid (1) [19].

Figure 3.

(a) Overview of the clavam (11) and clavulanic acid (1) pathways. (b) Overview of the “simple” carbapenem pathway to carbapenem-3-carboxylate (14) in Gram-negative enterobacteria and the “complex” pathway to thienamycin (2) in Gram-positive actinobacteria.

After β-lactam formation, the carbapenem pathway also bifurcates, but in a strikingly different fashion. Phylogenetically remote from the “complex” carbapenems represented by thienamycin (2) and ~50 congeners from Actinobacteria, carbapenem-3-carboxylic acid (C3C, 14) is produced by a limited number of γ-proteobacteria. Despite their evolutionary distance, their first two biosynthetic steps are mediated by identical chemistry executed by homologous pairs of enzymes, CarB/ThnE and CarA/ThnM [20]. The “simple”carbapenem 14, however, is formed by an exceptional member of the non-heme iron, α-KG dependent oxygenases, CarC, which inverts the bridgehead stereochemistry of 12 to form the co-occurring carbapenam 13, which either during the same catalytic cycle or in a separate oxidation, is desaturated to C3C (14) [21,22]. The hydrogen at the substrate bridgehead (H°) is lost in this process and replaced with inversion from a tyrosyl residue in CarC (H) [23,24]. The details of this overall conversion involving both formally non-oxidative and oxidative half-reaction steps remain unclear.

By interesting comparison, the thienamycin [25] and other carbapenem biosynthetic clusters [26] do not encode a CarC homolog. It would appear an entirely different biochemical solution has evolved in these more complex structures to carry out the key stereochemical inversion and desaturation steps. In addition, evidence has been collected to show that the C-2 thioether sidechain is derived from stepwise truncation of coenzyme A (box, Figure 3B) [27] and recently it has been demonstrated that ThnK, one of three cobalamin-dependent radical SAM enzymes in the pathway, adds two SAM-derived methyl groups sequentially at C-6 of 15, but after sulfur insertion at C-2 has occurred [28].

The timing and mechanism of many other biosynthetic events in the thienamycin pathway remain a mystery. But, as will become apparent by comparison below to the NRPS-centered β-lactam biosynthetic pathways, in both clavulanic acid and thienamycin, the β-lactam rings are created relatively early in their respective pathways, but in an absolute configuration where they lack their ultimate biological activity as inhibitors of bacterial cell wall biosynthesis. However, in both very late oxidative events ensue to invert bicyclic ring geometries to potent biological function (cf. reaction of CarC in Figure 3B).

NRPS-Dependent Pathways, Penicillin and Cephalosporin

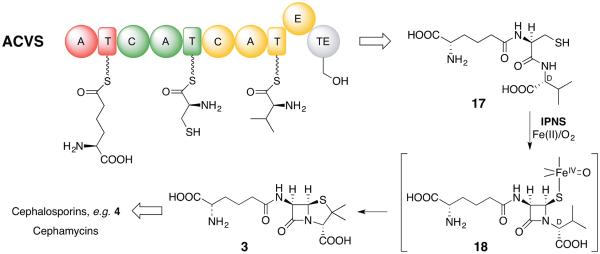

One of the earliest and most thoroughly studied NRPS enzyme is L-δ-(α-aminoadipoyl)-L-cysteinyl-D-valine synthetase (ACVS) [29] that underlies the biosynthesis of penicillin and cephalosporin. It has been isolated, or cloned and over-produced from a number of fungal and bacterial sources as a monomer (400–430 kDa). It is the paradigm Type A, linear NRPS enzyme [30]. These enzymes exemplify the canonical linear thiotemplate model of NRPS function, which in the case of ACVS comprises 10 domains, each with a specific and essential synthetic role. As illustrated in Figure 4, the adenylation (A) domains A1, A2 and A3 all bind ATP and selectively L-α-aminoadipic acid, L-cysteine and L-valine, respectively. In each A domain its substrate amino acid is acyladenylated and the activated substrate is captured by the directly downstream peptidyl-carrier protein (PCP), which, like acyl-carrier proteins (ACPs) in fatty acid and polyketide biosynthesis, has been post-translationally modified to link a 4'-phosphopantethienyl “arm” that bears its substrate amino acid as the S-terminal thioester shown in Figure 4. The repeated domain architecture defines modules, each activating its particular amino acid building block. At the interfaces between modules lie condensation (C) domains that react the upstream thioester (acyl donor) with the intramodule α-aminothioester (acyl acceptor) to generate a peptide bond. The resulting L,L-dipeptide bound to PCP2 is then extended to the L,L,L-tripeptide bound to PCP3, which is epimerized in the single epimerase (E) domain to an equilibrating mixture of disastereomeric L,L,L- and L,L,D-ACV PCP3 thioesters, the latter of which is selectively transferred to and hydrolyzed in the thioesterase (TE) domain to release the L,L,D-ACV tripeptide (17).

Figure 4.

Module and domain organization of L-δ-(α-aminoadipyl)-L-cysteinyl-D-valine synthetase (ACVS) and the stepwise oxidative cyclization of ACV to isopenicillin N (3) by isopenicillin N synthase. After epimerization of the N-terminus of 3 from L- to D-, successive α-KG dependent non-heme iron enzymes act to carry out oxidative ring expansion to the cephem nucleus, allylic oxidation and, finally, oxidation and O-methylation at C-7 to give cephamycins.

This paradigm product of the thiotemplate model is then the substrate for one of the most impressive enzymes in natural products chemistry, isopenicillin N synthase (IPNS), a non-heme iron, non-α-KG dependent oxygenase. At a single metal center the tripeptide 17 reacts in a stepwise manner, first to the monocyclic β-lactam 18 and, second, fuses the thiazolidine ring with the net loss of four substrate hydrogens to isopenicillin N (3). Synthesis of the substantially more strained bicyclic penicillin nucleus is thermodynamically easily achieved owing to the co-reduction of a molecule of dioxygen to two equivalents of water (cf. 2H2 + O2 —> 2H2O, ΔG >100 kcal/mol). Although non-heme iron oxygenases appear in a number of transformations in β-lactam antibiotic biosynthesis, this is the single known instance where one catalyzes β-lactam ring synthesis, and does so directly to the antibiotic-active stereochemistry. The other non-heme iron oxygenases are all α-KG dependent. Some are illustrated in Scheme 2, and the remainder figure prominently in the oxidative ring expansion of the penicillin nucleus to the cephems (after epimerization at the N-terminus, cf. 3 and 4), followed by allylic oxidation and acetylation to give cephalosporin C (4). Further oxidation at C-7 and methylation can also occur to give cephamycins [31].

NRPS-Dependent Pathways, Nocardicin and Monobactams

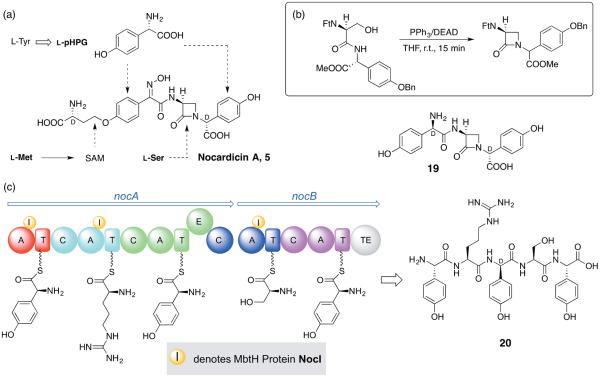

The non-proteinogenic amino acid L-(p-hydroxyphenyl)glycine (pHPG) present twice in nocardicin A (5) [32] and the peptide connectivity in the monobactam sulfazecin (6), reminiscent of the natural penicillins and cephalosporins (e.g. 3 and 4), connote their origins by NRPS assembly. Isotopic labelling experiments established that the monocyclic β-lactam rings present in nocardicin A and related monobactams are derived from L-serine with no change in oxidation state at the β-carbon [33,34], which implied, unlike penicillin, a common, non-oxidative route to the azetidinone ring (Figure 5A). Incorporation of serine stereospecifically labelled at C-3 with deuterium unambiguously demonstrated that the C-N bond formation in nocardicin A (5) occurs with clean inversion of configuration [35]. This observation and other radiolabeling experiments at the time were interpreted to suggest an intramolecular (SNi) displacement in a hypothetical peptide precursor by amide nitrogen of an activated seryl hydroxyl to achieve 4-membered ring formation [36] Such a synthetic strategy was successfully mimicked in the highly efficient adaptation of the Mitsunobu reaction from a simple model reaction (Figure 5B, FtN = N-phthaloyl, DEAD = diethyldiazodicarboxylate) to the total synthesis of all the known nocardicins, which confirmed or established all stereocenters [37]. The synthesis of optically pure nocardicin A, for example, proceeded from unprotected L-serine in an overall 23% yield. In an important experiment, nocardicin G (19, D,L,D-configuration), the simplest of the known nocardicins, could be demonstrated in a whole-cell experiment to be incorporated intact into nocardicin A, making it likely the earliest β-lactam containing intermediate in the pathway [38].

Figure 5.

(a) Summary of whole-cell incorporation experiments to establish the amino acid building blocks of nocardicin A (5). (b) Model reaction of β-lactam formation under Mitsunobu conditions gave a 3:2 mixture of diasteromeric products shown (Ft = N-phthaloyl, DEAD = diethyl diazodicarboxylate, Bn = benzyl). (c) Module and domain organization of NocA and NocB with NocI bound in trans to A1, A2 and A4, which need this MbtH superfamily protein to observe PPi exchange in vitro. The predicted product of canonical linear NRPS synthesis is L-pHPG–L-Arg–D-pHPG–L-Ser–L-pHPG (20).

The O-homoseryl modification seen in about half of the nocardicins is derived from methionine. Isolation, purification and N-terminal amino acid sequence data from this unusual SAM-dependent 3-amino-3-carboxypropyl transferase enabled the nocardicin biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) to be defined by reverse genetics [39,40]. The D,L,D-tripeptide core of nocardicin G (19) led us to expect that, like the tripeptide core of penicillin from ACV synthetase (Figure 4, ACVS),[41] a 3-module NRPS would be present in the BGC. In fact, the NRPSs NocA/B house five modules supporting, in principle, synthesis of the pentapeptide 20 (Figure 5C). Our inability to express these proteins in Streptomyces hosts, or individual modules and even A-domains in Streptomyces or E. coli to identify their substrate amino acids gave birth to an A domain substrate prediction algorithm [42,43] that has found wide use, and then the Udwary-Merski Algorithm (UMA) to predict linker regions between domains to cut these giant enzymes down to experimentally tractable pieces [44]. The former predicted A1, A3 and A5 activate pHPG, A4 Ser and A2 ambiguously ornithine or N-hydroxyornithine. Since only M3 has an epimerization domain, it was thought M1 and M2 might be inactive. This possibility was strengthened by inserts of short, repeated sequences not seen in other NRPSs comprising ~40 residues in M1 and ~90 in M2 [40]. Later after developing a double gene replacement strategy, each with its own selection, it was possible to introduce “scarless” mutations in vivo and thereby establish that all five modules are required for antibiotic biosynthesis despite the long insertions and other anomalies evident in the sequences of NocA and NocB [45]. In time A3 and A5 were demonstrated to give PPi exchange with L-pHPG (but not D-pHPG), as predicted. Questioning why native NocB isolated from N. unformis catalyzed PPi exchange specifically with L-Ser [40], but not the E. coli expressed A4 domain, led us to discover the missing component between wild-type NocB and the recombinant A domains was NocI, a member of the MbtH superfamily of auxiliary proteins encoded in most NRPS clusters. This pivotal advance made by Jeanne Davidsen was soon reported elsewhere [46,47] but finally allowed the function of every A domain to be experimentally determined. A1 was confirmed for L-pHPG and A4 for L-Ser, but the enigmatic A2 was found to be specific for L-Arg.[48] A1, A2 and A4 require NocI for activity and bind NocI in a 1:1 stoichiometry. In contrast, the exchange activities of A3 and A5 are unaffected by the presence of NocI. In sum, the data supported linear behavior for NocA/B to produce the pentapeptide L-pHPG–L-Arg–D-pHPG–L-Ser–L-pHPG (20) [48].

The long-sought identification of L-Arg as the substrate for M2 was the lynchpin to further progress unraveling the nocardicin biosynthetic pathway. Puzzling questions remained apart from the central issue of how β-lactam ring formation took place. With it now clear that all five modules of NocA/B were active and required for biosynthesis, the first two L-configured amino acids must be lost and the tripeptide core of nocardicin G (19) therefore is derived from the remaining three residues. However, while an epimerization (E) domain resides in M3 to establish the D-configuration in the N-terminal pHPG of nocardicin G, there was no comparable E domain in M5 to similarly set the C-terminal stereochemistry.

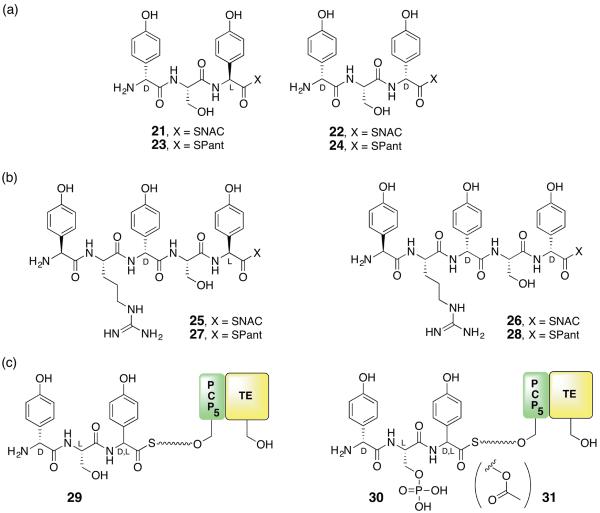

The working hypothesis at the time was that monocyclic β-lactam formation occurred by an SNi process, synthetically precedented as noted above [49] and consistent with stereochemical inversion observed at the seryl β-carbon [35]. Such a process could be visualized to take place after peptide release from NocB, or while still bound to NocA/B, but logically in M5 after addition of the last pHPG unit. To answer these questions, we elected to excise the TE domain from NocB and attempt to identify what product it releases. This task required the stereocontrolled preparation of tri- and pentapeptides, which, owing to the base sensitivity of the pHPG α-centers (especially as thioesters or activated acyl intermediates in peptide coupling reactions), proved technically and analytically demanding [50,51]. First, the diastereomeric D,L,L- and D,L,D- pHPG–Ser–pHPG N-acetylcysteamine (SNAC) thioesters 21 and 22 were synthesized (Figure 6A). To our surprise, no reaction could be detected in the presence of the TE domain beyond slow hydrolysis at a rate indistinguishable from a Ser—>Ala active site control. Similar results were obtained for the corresponding pantethienyl (SPant) tripeptides 23 and 24. The corresponding L,L,D,L,L- and L,L,D,L,D- pHPG–Arg–pHPG–Ser–pHPG pentapeptide SNAC and SPant 25–28 were then synthesized (Figure 6B) and they too failed to give convincing reactions compared to the slow hydrolysis shown by control reactions. Next, considering that seryl O-activation prior to β-lactam formation might occur in trans while still bound to M5, the seryl O-phosphoryl and O-acetyl tripeptide SPant thioesters were assembled. They also did not react. In a final escalation of technical difficulty, the D,L,L- and D,L,D-tripeptide-CoA, the seryl O-phosphorylated and O-acetylated tripeptide-CoA esters were prepared and coupled using Sfp to the apo-PCP4-TE didomain to give 29, 30 and 31 (Figure 6C) Even now in the presence of an in cis TE, no reaction was observed [52].

Figure 6.

(a) Tripeptide and (b) pentapeptide N-acetylcysteamine (SNAC) and S-pantethienyl (SPant) mimicks of the potential peptide products of NocA/B tested for reaction in the thioesterase (TE) domain. (c) In the course of preparing the tripeptides 29, 30 and 31 directly bound to the module 5 peptidyl carrier-domain–thioesterase didomain (PCP5–TE), epimerization at the C-terminus was observed and unavoidable.

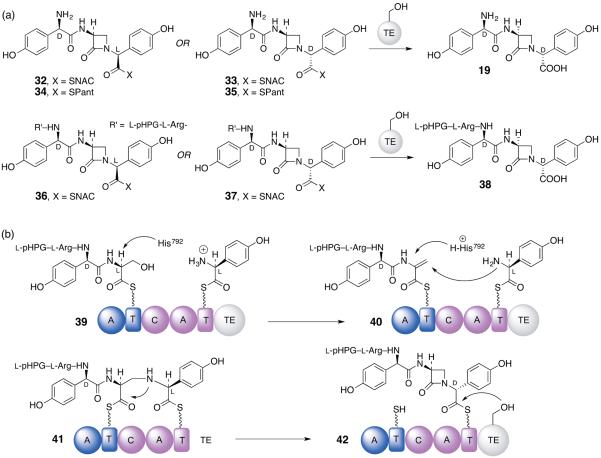

Faced with this exquisite level of substrate discrimination by the NocB TE domain, there was only one simple alternative and that was β-lactam synthesis was occurring upstream in M5 prior to product release in the TE. Thus, the corresponding tri- and pentapeptide SNAC and SPant thioesters 32–37 now bearing an embedded β-lactam ring in place of the L-seryl residue were synthesized and tested. To our profound relief, yet further surprise, the respective diastereomeric pairs of the former afforded nocardicin G (19, D,L,D) rapidly as a single stereoisomer with no detectable epi-nocardicin G (19, but D,L,L), or, correspondingly from the latter, pro-nocardicin G (38, L,L,D,L,D) only was obtained (Figure 7A). The immaculate epimerization in M5 had been committed by the TE itself in addition to stereospecific hydrolytic product release. Detailed kinetic analysis of the D,L,L- and D,L,D-SNAC thioester solution rates of epimerization and hydrolysis compared to the TE-catalyzed rates for each diastereomer showed dramatic accelerations for enzyme-catalyzed epimerization (>1400 fold) and that product release was ~10 times faster than epimerization [50,52]. To determine whether a tripeptide or pentapeptide was preferred by the TE, the C-terminal D-configured SNAC peptides 33 and 37 were mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio for a direct competition assay. In keeping with the requirement for all five modules of NocA/B to observe antibiotic production in vivo, the pentapeptide β-lactam 37 was the dominant substrate by a factor of at least 20. The role of an NRPS TE as an epimerase is unprecedented, but becomes possible even as the TE-bound O-seryl (oxy)ester because the pHPG α-hydrogen is benzylic and its acidity is enhanced by a factor of 106-107 compared to other α-amino acids [52].

Figure 7.

(a) Diastereomeric D,L,L- and D,L,D-tripeptides and L,L,D,L,L- and L,L,D,L,D-pentapeptides that contain an embedded β-lactam rig in place of a seryl residue activated as substrate-like thioesters for possible reaction in the TE. (b) Proposed mechanism of β-lactam formation in the condensation (C) domain of module 5 followed by C-terminal epimerization (L- to D-) and hydrolytic product release.

Although complete stereoinversion of the C-terminal pHPG residue from L- to D- was achieved autonomously in the TE domain, in no experiment conducted above was β-lactam formation observed. This cyclization event must take place in M5 either in cis relying on the synthetic capabilities of the NRPS itself, or in trans through the intervention of auxiliary enzyme(s) that was/were not obviously encoded in the BGC [53]. As neither mechanistic alternative had been encountered before, exploration of the former was undertaken first. To approach self-catalyzed reaction in as unbiased a way possible, all of M5–TE was expressed as a single construct with the aim to separately introduce tetrapeptide acyl donors and in the hope that M5 would bind ATP and L-pHPG and present this amino acid in C5 to either successfully reconstitute pro-nocardicin G synthesis or not. Presentation to M5–TE of L-pHPG–L-Arg–D-pHPG–L-Ser linked to PCP4 together with ATP and L-pHPG resulted in remarkably smooth conversion to pro-nocardicin G (38). In sharp contrast, however, this tetrapeptide as either its SNAC or SPant thioester was completely unable to support synthesis—unlike our experience above with the TE domain. Moreover, supplying the dipeptide D-pHPG–L-Ser SNAC, SPant or PCP4 thioesters were all unsuccessful. Contrary to the sense of the literature, albeit from a limited data set, that C-domains are flexible with respect to their acyl donor tolerance [54], M5 of the nocardicin NRPS system appears to be highly selective.

With the TE domain unlikely to be the seat of β-lactam formation, the condensation domain, C5, was examined for its potential to catalyze this unprecedented reaction. Immediately apparent was an “extra” His residue (H792) just N-terminal to the HHxxxDG catalytic motif conserved among C domains and associated with canonical peptide bond synthesis [54,55]. A series of Ala substitution mutagenesis experiments suggested a role for this His residue, which could be visualized as both a base and then conjugate acid in its protonated (histidinium) form to mediate a β-elimination of hydroxide (water) from 39 to the dehydroalanyl tetrapeptide intermediate 40, followed by a β-addition of the pHPG amine giving C-N bond formation with net stereochemical inversion in 41, as demanded by earlier experiment, and proton donation at the α-carbon with overall retention. A series of experiments is underway to test and support this now third mechanism of β-lactam biosynthesis. It is noted that, like isopenicillin N (3), nocardicin G (19) and, consequently, the nocardicins are created in the biologically-active absolute configuration.

Conclusions

The mechanism of cell wall crosslinking by D,D-transpeptidases is highly conserved among bacteria. These enzymes are members of a single evolutionary clan of serine hydrolases and share key structural and mechanistic features that are identified by the β-lactam antibiotics, which selectively inhibit them. Their small size and matched recognition and binding elements enable them to compete for the active site and inactivate it by deformation and covalent adduct formation. Fundamental to this ability to inactivate is the accurate presentation of a substrate-like amide bond (the β-lactam) whose intrinsic reactivity is greater than the natural muramyl pentpeptide owing to ring strain and stereoelectronic effects. It is impressive, if not inspiring, that five biosynthetically distinct subclasses of β-lactam antibiotics have evolved, each created by widely different synthetic means. Thermodynamically unfavorable β-lactam ring formation is more than paid for in the bicyclic penicillin by the concomitant reduction of molecular oxygen to two water molecules, but more modestly in clavulanic acid and the carbapenems by the hydrolysis of ATP, and, finally, in the monocyclic synthesis of the nocardicins by the conversion of a thioester to an amide. Additional potential energy can be introduced by fusion of a second ring to the β-lactam and further increased by a C-C double bond and electronic effects communicated through them. A notable variation on this pattern is the monobactams where now a comparatively less reactive monocyclic β-lactam template is substantially amplified by N-sulfonation. Many biosynthetic questions remain in most of these subclasses that are the subjects of active investigation.

Resistance to the principally used β-lactam antibiotics continues to increase, undermining their clinical usefulness [56]. One major source of resistance is β-lactamases, soluble enzymes themselves evolved from the membrane-associated D,D-transpeptidases (PBPs)—that is, they are all members of the same hydrolase clan [1,2]. Another recently discovered source of resistance to most β-lactam antibiotics, however, is the L,D-transpeptidases that provide bacteria a backup strategy to carry out peptidoglycan synthesis. These enzymes mediate muramyl peptide crosslinking functionally similar to the D,D-transpeptidases, but react the tetrapeptide stem after hydrolytic loss of the C-terminal D-Ala with the third amino acid residue on a nearby peptide strand (diaminopimelate, lysine) to create a 3,3-crosslink. The L,D-transpeptidases are cysteine proteases and members of a different protease clan evolutionarily and structurally distinct from the D,D-transpeptidases. They were first identified in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis, a disease long known not to be treatable with penicillin [57]. Despite their functional, indeed mechanistic, similarity and use of the same nucleophile (acyl acceptor), most β-lactam inhibitors of the latter are not effective against the former. Hope has been raised more recently that, in fact, select members of the carbapenem subclass show crossover reactivity to inactivate both D,D- and L,D-transpeptidases [58], which could be a basis for their largely empirically determined potency and broad spectrum activity.

Antibiotic resistance is a major and ominous threat to human health. Deeper investigation of the fundamental dynamics of the clinically relevant serine, cysteine and threonine proteases (>20 clans) is essential to both root understanding of mechanism and doubtless subtle, but important, differences that should guide not only the design and synthesis of new or improved β-lactams to meet this public health challenge, but other protease targets of therapeutic interest. Hand-in-hand with these tasks are synthesis and production where one can now contemplate combining and engineering the functionally diverse enzymes uncovered in biosynthetic studies of these valuable natural products to manufacture new and hybrid drugs by fermentation and semi-synthetic means.

Figure 1.

Representative structures of the five known subclasses of β-lactam antibiotics.

Acknowledgements

It is with deep and enduring gratitude that I thank the students and postdoctoral fellows who have contributed to the β-lactam biosynthesis problems in my laboratory. Their research has been sustained by support from the National Institutes of Health [AI014937].

References

- 1.Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Finn R. Twenty years of the MEROPS database of proteolytic enzymes, their substrates and inhibitors. Nucl Acids Res. 2016;44:D343–D350. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This database is extremely useful for the study of evolutionary convergence, yet tolerable differences in active site geometry for catalytic function.

- 2.Buller AR, Townsend CA. Intrinsic evolutionary constraints on protease structure, enzyme acylation, and the identity of the catalytic triad. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E653–E661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221050110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• This article, with extensive Supplementary Information, introduces a formalism to reanalyze the reactive rotamer and oxyanion hole of all serine, cysteine and threonine proteases of independent lineage and, where possible, their inhibitors.

- 3.Walsh C, Wencewitz T. Antibiotics: Challenges, Mechanisms, Opportunities. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doroghazi JR, Albright JC, Goering AW, Ju K-S, Haines RR, Tchalukov KA, Labeda DP, Kelleher NL, Metcalf WW. A roadmap for natural product discovery based on large-scale genomics and metabolomics. Nature Chem Biol. 2014;10:963–968. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bachmann BO, Li R, Townsend CA. beta-Lactam synthetase: a new biosynthetic enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:9082–9086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This is one notable method to categorize the biosynthetic potential of bacterial genomes.

- 6.McNaughton HJ, Thirkettle JE, Zhang Z, Schofield CJ, Jensen SE, Barton B, Greaves P. β-Lactam Synthetase: Implications for β-Lactamase Evolution. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1998:2325–2326. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerratana B, Stapon A, Townsend CA. Inhibition and alternate substrate studies on the mechanism of carbapenam synthetase from Erwinia caratovora. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7836–7847. doi: 10.1021/bi034361d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parr IB, Boehlein SK, Dribben AB, Schuster SM, Richards NG. Mapping the aspartic acid binding site of Escherichia coli asparagine synthetase B using substrate analogs. J Med Chem. 1996;39:2367–2378. doi: 10.1021/jm9601009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tesson AR, Soper TS, Ciustea M, Richards NG. Revisiting the steady state kinetic mechanism of glutamine-dependent asparagine synthetase from Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;413:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller MT, Bachmann BO, Townsend CA, Rosenzweig AG. Structure of β-lactam synthetase reveals how to synthesize antibiotics instead of aspargine. Nature Struct Biol. 2001;8:684–689. doi: 10.1038/90394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller MT, Bachmann BO, Townsend CA, Rosenzweig AG. The catalytic cycle of β-lactam synthetase observed by X-ray crystallographic snapshots. Proc Nat'l Acad Sci, USA. 2002;99:14752–14757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232361199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Comparatively few x-ray crystallograpic studies give “snapshots” of a full catalytic cycle like this one and intimate views of substrates and enzyme along the reaction coordinate.

- 12.Raber ML, Arnett SO, Townsend CA. A conserved tyrosyl-glutamyl catalytic dyad in evolutionarily linked enzymes: carbapenem synthetase and β-lactam synthetase. Biochemistry. 2009;48:4959–4971. doi: 10.1021/bi900432n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A series of kinetics experiments gives a detailed view of enzyme function.

- 13.Khaleeli N, Li R-F, Townsend CA. Origin of the β-lactam carbons in clavulanic acid from an unusual thiamine pyrophosphate-mediated reaction. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9223–9224. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caines MEC, Elkins JM, Hewitson KS, Schofield C. Crystal Structure and Mechanistic Implications of N2-(2-Carboxyethyl)arginine Synthease, the First Enzyme in the Clavulanic Acid Biosynthetic Pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5685–5692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merski M, Townsend CA. Observation of an acryloy-thiamin diphosphate adduct in the first step of clavulanic acid biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15750–15751. doi: 10.1021/ja076704r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • A thiamin-bound acryloyl intermediate is detected with unexpected UV absorption properties.

- 16.Sleeman MC, Schofield CJ. Carboxymethylproline synthase (CarB), an unusual carbon-carbon bond-forming enzyme of the crotonase superfamily involved in carbapenem biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6730–6736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311824200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerratana B, Arnett SO, Stapon A, Townsend CA. Carboxymethylproline synthase from Pectobacterium carotorvora: a multifaceted member of the crotonase superfamily. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15936–15945. doi: 10.1021/bi0483662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krol WJ, Townsend CA. The role of molecular oxygen in clavulanic acid biosynthesis: evidence of a bacterial oxidative deamination. J Chem Soc, Chem Commun. 1988:1234–1236. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fulston M, Davison M, Elson SW, Nicholson NH, Tyler JW, Woroniecki SR. Clavulanic acid biosynthesis: final steps. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. I. 2001:1122–1130. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bodner MJ, Li R, Phelan RM, Freeman MF, Moshos KA, Lloyd EP, Townsend CA. Definition of the common and divergent steps in carbapenem β-lactam antibiotic biosynthesis. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:2159–2165. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stapon A, Li R-F, Townsend CA. Carbapenem biosynthesis: confirmation of stereochemical assignments and the role of CarC in the ring stereoinversion process from L-proline. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:8486–8493. doi: 10.1021/ja034248a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sleeman MC, Smith P, Kellam B, Chhabra SR, Bycroft BW, Schofield CJ. Biosynthesis of carbapenem antibiotics: new carbapenam substrates for carbapenem synthase (CarC) Chembiochem. 2004;5:879–882. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stapon A, Li R, Townsend CA. Synthesis of (3S,5R)-carbapenam-3-carboxylic acid and its role in carbapenem biosynthesis and the stereoinversion problem. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15746–15747. doi: 10.1021/ja037665w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chang W-c, Guo Y, Wang C, Butch SE, Rosenzweig AC, Boal AK, Krebs C, Bollinger JM., Jr Mechanism of the C5 Stereoinversion Reaction in the Biosynthesis of Carbapenem Antibiotics. Science. 2014;343:1140–1144. doi: 10.1126/science.1248000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nunez LE, Mendez C, Brana A, Blanco G, Salas JA. The biosynthetic gene cluster for the β-lactam carbapenem thienamycin in Streptomyces cattleya. Chem Biol. 2003;10:301–311. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(03)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li RF, Lloyd EP, Moshos KA, Townsend CA. Identification and Characterization of the Carbapenem MM4550 and its Gene Cluster in Streptomyces argenteolus ATCC 11099. ChemBioChem. 2014;15:320–331. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman MF, Moshos KA, Bodner MJ, Li R, Townsend CA. Four enzymes define the incorporation of coenzyme A in thienamycin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:11128–11133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804500105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marous DR, Lloyd EP, Buller AR, Moshos KA, Grove TL, Blaszczyk AJ, Booker SJ, Townsend CA. Consecutive radical S-adenosylmethionine methylations form the ethyl side chain in thienamycin biosynthesis. Proc Nat'l Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:10354–10358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508615112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This paper describes the first experimentally demonstrated example of successive methyl transfers by a single radical SAM enzyme. It is striking for the two highly dissimilar environments in which the reactions occur.

- 29.Byford MF, Baldwin JE, Shiau C-Y, Schofield CJ. The Mechanism of ACV Synthetase. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2631–2649. doi: 10.1021/cr960018l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mootz HD, Schwartzer D, Marahiel MA. Ways of assembling complex natural products on modular non-ribosomal peptide synthetases. ChemBioChem. 2002;3:491–504. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020603)3:6<490::AID-CBIC490>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamed RB, Gomez-Castellanos JR, Henry L, Ducho C, McDonough MA, Schofield CJ. The enzymes of β-lactam biosynthesis. Nat Prod Rep. 2013;30:210–107. doi: 10.1039/c2np20065a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Townsend CA, Brown AM. Nocardicin A: Biosynthetic Experiments with Amino Acid Precursors. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:913–918. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Townsend CA, Brown AM. Biosynthetic Studies of Nocardicin A. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:2873–2874. [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Sullivan J, Gillum AM, Aklonis CA, Souser ML, Sykes RB. Biosynthesis of Monobactam Compounds: Origin of the Carbon Atoms in the β-Lactam Ring. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;21:558–564. doi: 10.1128/aac.21.4.558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Townsend CA, Brown AM. Nocardicin A Biosynthesis: Stereochemical Course of Monocyclic β-Lactam Formation. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:1748–1750. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Townsend CA, Brown AM, Nguyen LT. Nocardicin A: Stereochemical and Biomimetic Studies of Monocyclic β-Lactam Formation. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:919–927. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salituro GM, Townsend CA. Total Synthses of (−)-Nocardicins A—G: A Biogenetic Approach. J Amer Chem Soc. 1990;112:760–770. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Townsend CA, Wilson BA. The Role of Nocardicin G in Nocardicin A Biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:3320–3321. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reeve AM, Breazeale SD, Townsend CA. Purification, Characterization and Cloning of an S-Adenosylmethionine-Dependent 3-Amino-3-Carboxypropyl Transferase in Nocardicin Biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30695–30703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gunsior M, Breazeale SD, Lind AJ, Ravel J, Janc JW, Townsend CA. The Biosynthetic Gene Cluster for a Monocyclic [beta]β-Lactam Antibiotic, Nocardicin A. Chem Biol. 2004;11:927–938. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marahiel MA, Essen L-O. Nonribosomal peptide synthetaes: Mechanistic and structural aspects of essential domains. Meth Enzymol. 2009;458:337–351. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)04813-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Challis GL, Ravel J, Townsend CA. Predictive, structure-based model of amino acid recognition by nonribosomal peptide synthetase adenylation domains. Chem Biol. 2000;7:211–224. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stachelhaus T, Mootz HD, Marahiel MA. The specificity-conferring code of adenylation domains in nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Chem Biol. 1999;6:493–505. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80082-9. See also. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Udwary DW, Merski M, Townsend CA. A method for prediction of the locations of linker regions within large multifunctional proteins, and application to a Type I polyketide synthase. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:585–598. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00972-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davidsen JM, Townsend CA. In vivo characterization of nonribosomal peptide synthetases NocA and NocB in the biosynthesis of nocardicin A. Chem Biol. 2012;19:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • The double gene replacement strategy reported here to introduce mutations in vivo is a general one that can applied more widely to query specific sites in the context of the whole BGC.

- 46.Felnagle EA, Barkei JJ, Park H, Podevels AM, McMahon MD, W DD, Thomas MG. MbtH-like proteins as integral components of bacterial nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8815–8817. doi: 10.1021/bi1012854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang W, Heemstra JR, Walsh CT. Activation of the pacidamycin PacL adenylation domain by MbtH-like proteins. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9946–9947. doi: 10.1021/bi101539b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davidsen JM, Bartley DM, Townsend CA. Non-ribosomal propeptide precursor in nocardicin A biosynthesis predicted from adenylation domain specificity dependent on the MtbH family protein NocI. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:1749–1759. doi: 10.1021/ja307710d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Townsend CA, Salituro GM, Nguyen LT, DiNovi MJ. Biogenetically-modelled total synthesis of (−)-nocardicin A and (−)-nocardicin G. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:3819–3822. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gaudelli NM, Townsend CA. Stereocontrolled Synthesis of Peptide Thioesters Containing Modified Seryl Residues as Probes of Antibiotic Biosynthesis. J Org Chem. 2013;78:6412–6426. doi: 10.1021/jo4007893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brieck C, Cryle MJ. A Facile Fmoc Solid Phase Synthesis Strategy To Access Epimerization-Prone Biosynthetic Intermediates of Glycopeptide Antibiotics. Org Lett. 2014;16:2454–2457. doi: 10.1021/ol500840f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This paper presents an alternative strategy for controling phenylglycine α-stereochemistry during peptide synthesis.

- 52.Gaudelli NM, Townsend CA. Epimerization and High Substrate Gating by a Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetase TE Domain in Monocyclic β-Lactam Antibiotic Biosynthesis. Nature Chem Biol. 2014;9:251–258. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Detailed kinetic comparisons between solution and enzyme-mediated rates of epimerization and hydrolysis are described to clearly establish the role of the thioesterase domain.

- 53.Gaudelli NM, Long DH, Townsend CA. β-Lactam formation by a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase during antibiotic biosynthesis. Nature. 2015;520:383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature14100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• The third natural mechanism of β-lactam biosynthesis is described in an NRPS condensation domain that converts a seryl residue into the 4-membered ring embedded in a peptide.

- 54.Sieber SA, Marahiel MA. Molecular mechanisms underlying nonribosomal peptide synthesis: approaches to new antibiotics. Chem Rev. 2005;105:715–738. doi: 10.1021/cr0301191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bloudoff K, Alonzo DA, Schmeing TM. Chemical Probes Allow Structural Insight into the Condensation Reaction of Nonribosomal Peptide Synthetases. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown ED, Wright GD. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature. 2016;529:336–343. doi: 10.1038/nature17042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lavollay M, Arthur M, Fourgeaud M, Dubost L, Marie A, Veziris N, Blanot D, Gutmann L, Mainardi J-L. The Peptidoglycan of Stationary-Phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis Predominantly Contains Cross-Links Generated by L,D-Transpeptidation. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4360–4366. doi: 10.1128/JB.00239-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cordillot M, Dubee V, Triboulet S, Dubost L, Marie A, Hugonnet J-E, Arthur M, Mainardi J-L. In Vitro Cross-Linking of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Peptidoglycan by L,D-Transpeptidases and Inactivation of These Enzymes by Carbapenems. Antimicrob Agent Chemother. 2013;57:5940–5945. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01663-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]