Abstract

The global Protein Data Bank (PDB) was the first open-access digital archive in biology. The history and evolution of the PDB are described, together with the ways in which molecular structural biology data and information are collected, curated, validated, archived, and disseminated by the members of the Worldwide Protein Data Bank organization (wwPDB; http://wwpdb.org). Particular emphasis is placed on the role of community in establishing the standards and policies by which the PDB archive is managed day-to-day.

Historical Background

Structural biology is a relatively young science that can trace its roots to the first X-ray diffraction studies of pepsin in 1935 by Dorothy Crowfoot (Hodgkin), who at the time was a student of J.D. Bernal [1]. Twenty years later, Kendrew determined the structure of myoglobin [2,3]; shortly thereafter, Perutz determined the structure of hemoglobin [4,5]. Both won Nobel prizes for their achievements. Not long after these structures were published, the crystallographic community began discussions as to how to best archive these data and make them available. During this period, there were numerous grassroots meetings, one of which resulted in a petition, and many exchanges of handwritten documents. In 1971, the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory hosted a symposium on protein crystallography, during which leaders in the field presented their seminal work [6]. Walter Hamilton, an attendee, offered to provide the first home for what is now known as the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [7]. The PDB was launched at Brookhaven National Laboratory, based on the Protein Structure Library created by Edgar Meyer [8]. The initial PDB archive contained fewer than ten structures, all of which were determined by X-ray crystallography. In the 1980s, structures determined using NMR methods began to be deposited, and in 1990 the first structure determined by electron microscopy was deposited. In 1982 the PDB reached 100 entries, in 1993 1,000 entries, in 1999 10,000, and in 2014 100,000 entries. At the time of writing, the PDB archive contains over 117,000 structures of proteins, nucleic acids, and their complexes with one another and with small molecule ligands.

The PDB as a Community Data Resource

From its inception, the PDB has been a community effort that has evolved with changes in scientific culture. For example, when the PDB was first created, data submission was voluntary. However, in the 1980s, members of the community became outspoken about the need to enforce mandatory data deposition. Various committees were set up to define what data should be required and when to disseminate the data. These guidelines were published in 1989, and over time, adopted by virtually all of the scientific journals that now require PDB deposition(s) as a prerequisite for publication of structural studies [9]. In 2008, further shifts in community sentiment led to mandatory deposition of experimental data together with atomic coordinates. In the current decade, the importance of reproducibility has been highlighted. The PDB convened method-specific Validation Task Forces and Workshops [10–13] to define what data should be collected and how best to validate the structural models, the experimental data, and the fit of the models to the data. Now every structure in the PDB comes with a publicly available validation report, and authors are strongly encouraged to include these reports with their manuscript submissions to journals.

The importance of global participation in data archiving was understood early in the creation of the PDB. Indeed, the announcement of the PDB in 1971 described the collaboration with the Cambridge Crystallographic Database Centre [7]. In 2003, a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) among partners in the US (RCSB Protein Data Bank; http://www.rcsb.org), Japan (Protein Data Bank Japan or PDBj; http://www.pdbj.org), and Europe (Protein Data Bank in Europe or PDBe; http://pdbe.org) established the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB) partnership, which is responsible for formalizing the procedures involved in collecting, standardizing, annotating and disseminating the data [14]. Subsequently, a global NMR specialist data repository BioMagResBank, composed of deposition sites in the US (BMRB; http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu) and Japan (PDBj-BMRB; http://bmrbdep.pdbj.org), joined the wwPDB.

The X-ray crystallography community has led the biological sciences in the area of data sharing. While the sociological/anthropological underpinnings of this leadership role have not been fully explored, much of what has transpired in the creation and evolution of the PDB can be traced to J.D. Bernal, who, in addition to being a brilliant scientific innovator, was a prominent social activist, whose beliefs were consistent with the conduct of the PDB [15].

Content of the PDB Archive

The PDB archive contains information about structural models that have been derived from experimental methods, including X-ray/neutron/electron crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, and 3D electron microscopy (3DEM). In addition to the 3D coordinates, the details of the chemistry of the polymers and small molecules are archived, as are metadata describing the experimental conditions, data-processing statistics and structural features such as the secondary and quaternary structure. The structure-factor amplitudes (or intensities) used to determine X-ray structures, and chemical shifts and restraints used in determining NMR structures are also archived. The electron density maps used to derive 3DEM models are archived in EMDB [16], and the experimental data underpinning them can be archived in EMPIAR [17]. In collaboration with community experts, pertinent data items are defined for each experimental field, with requirements evolving over time. The PDB data dictionary, originally developed to describe macromolecular crystallography, contains more than 4,400 data items. The dictionary combines data items common to all methods as well as those that are method specific. For example, the current dictionary contains 250 NMR- and 1200 3DEM-specific data definitions.

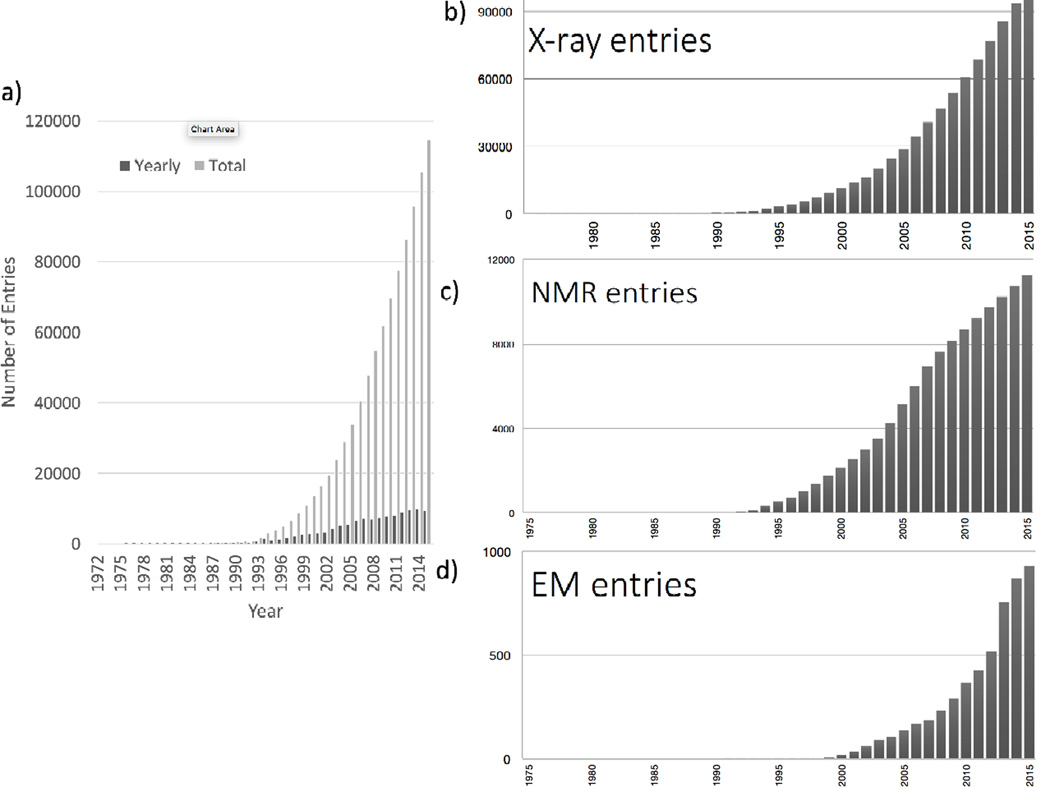

Over time, the holdings of the PDB have increased dramatically as has the complexity of the structures being archived (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Growth of the PDB archive. A) Number of entries deposited annually (dark grey) and available at the end of each year (light grey); B) number of X-ray crystal structures, C) NMR structures, and D) 3DEM structures available each year.

A workshop held in 2005 led to the policy that purely in silico models should not be part of the PDB [18], and, instead, a modeling portal should be created for these models. The Protein Modeling Portal was established in 2007 [19].

Representation of PDB Data

The first data format used by the PDB was established in the early 1970s and was based on the 80-column Hollerith format used for punched cards. The atom records included atom name, residue name and sequence number. A “header record” contained some metadata. This format was readily accepted because it was simple and both human- and machine-readable. However, it had many serious drawbacks in that the size of the structural models was limited to 99,999 atoms and that relationships among the data items were implicit. These inherent weaknesses meant that significant domain knowledge was necessary in order to write software using this format.

In the 1990s, the IUCr chartered a committee to create a more formal data model. This committee proposed the Macromolecular Crystallographic Information File (mmCIF) [20]. mmCIF is a self-defining format in which every data item has attributes describing its features including relationships to other data items. Most importantly, mmCIF has no limitations with respect to the size of the archived structural model. The dictionary and the data files are completely machine-readable, and no domain knowledge is required to read the files. The first dictionary contained over 3,000 data items relevant to X-ray crystallography. Over time, terms specific to NMR and 3DEM were added, and the dictionary was renamed PDBx/mmCIF. In 2007, it was decided that PDBx would be the Master Format for data collected by the PDB. In 2011, major X-ray structure determination software developers agreed to adopt this data model so that all output from their programs would be in PDBx. In 2015, large structures archived in the PDB that had formerly been split into multiple entries were combined into single entries and mmCIF formatted files. Other structural biology communities are in the process of building on the PDBx/mmCIF framework to establish their own controlled vocabulary and specialist data items [19,21].

PDBML, an XML format based on PDBx/mmCIF [22], and its RDF (Resource Description Framework) conversion were developed to facilitate the integration of structure data with other life sciences data resources could be facilitated [23].

The Data Pipeline

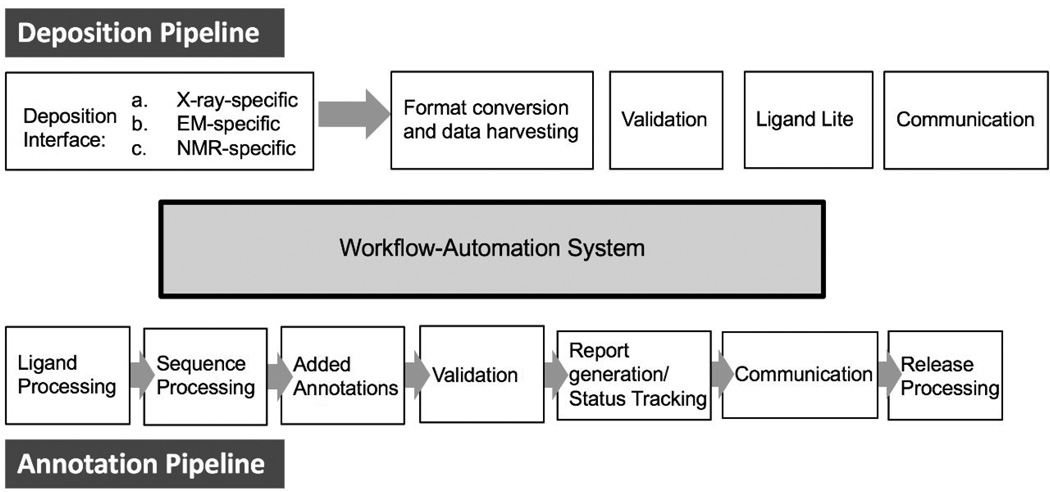

Every data resource has a set of procedures for deposition, curation, validation, archiving and dissemination of data. The pipeline currently used by the wwPDB to populate the PDB archive is illustrated schematically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

wwPDB Deposition, Annotation, and Validation pipeline. Each box represents a modular component of the data processing workflow.

In the very early days of the PDB, structures were deposited to BNL on magnetic tapes containing atomic coordinates with paper forms listing other data items, all sent first by mail and then via e-mail. A web-based system, called AutoDep, was created in the 1990s [24]. This system was later modified and used by PDBe [25] until very recently. The RCSB PDB and PDBj collected data using a system based on mmCIF called ADIT [26], and the BMRB in the US and its affiliate in Japan adopted a similar system called ADIT-NMR [27]. Although these systems were distinct, since 2003, the wwPDB partners have determined jointly what data should be collected and which procedures and algorithms should be used for data processing. In 2007, it was agreed within the wwPDB to create a single deposition,

Structures are made available to the public either immediately after they have been fully curated or -in most cases- when they are published in a journal. Usually, either the author or the journal informs wwPDB that the paper describing the structure is about to be published. PDB data are released in a two-stage process. Every Saturday at 03:00 UTC the polymer sequences, ligand SMILES strings, and crystallization pH for new structures designated for release are made public (http://wwpdb.org/download/downloads) as a courtesy to the protein structure modeling and computational chemistry communities to enable weekly blinded prediction challenge efforts (e.g., CAMEO [19], D3R CELPP [28]). Every Wednesday at 00:00 UTC, all new structures designated for release are made publicly available through the wwPDB FTP sites. On average about 200 structures are released every week. As evidence for the importance of this archive, in 2015, more than 500 million sets of atomic coordinates were downloaded from the wwPDB FTP sites.

Value-Added Resources

The wwPDB FTP sites provide the core data for many databases, services, and websites, including those run by the individual wwPDB partners. In the original wwPDB MOU, it was agreed that to best serve science, wwPDB partner websites would compete with one another and would offer many different kinds of services and features. The RCSB PDB has extensive search and reporting capabilities as well as an education portal called PDB-101 [26,29]. PDBe has multiple search and browse facilities as well as analysis and bioinformatics tools [30,31]. PDBj provides a variety of services and viewers and supports browsing in multiple Asian languages [23,32]. BMRB has many capabilities designed to serve the NMR community [33].

CATH [34] and SCOP [35,36] use the data in the PDB to classify the structural domains of proteins with an attempt to relate them to function. More recently, these two databases have agreed to work together and with other resources in the UK to provide predicted structural features under a unified system called Genome3D [37].

Additional specialty databases provide information on particular classes of macromolecules such as nucleic acids [38].

The Protein Structure Initiative (PSI) Structural Biology Knowledgebase (SBKB)[39] was an ambitious effort to unify information about protein sequence, structure and function. Unfortunately, the decision to discontinue funding the PSI means that this resource will cease to exist.

Challenges Going Forward

A review of the holdings of the PDB shows a steady growth (~10,000 new structures annually). More significantly, the complexity of the structural models continues to increase with more and more large heterogeneous assemblies entering the archive. Fortunately, there are no longer technical restrictions to receiving, annotating, validating, and disseminating these very large structures.

Historically, most structures were determined exclusively with the aid of a single experimental method: X-ray crystallography, NMR or 3DEM. In recent years, these traditional techniques are being combined with other methods to yield improved models. For example, it is now common practice to add data from small-angle scattering measurements to NMR-derived restraints to determine solution structures [40,41]. Similarly, NMR or X-ray data can be combined with cryoEM data in integrative modeling approaches [42]. Such integrative methods make it possible to combine data from different biophysical techniques with computational methods to create models of very large macromolecular machines [43]. However, hybrid approaches also present a variety of challenges including how to validate these structures and then how to archive them. As in the past, with the help and advice of an expert Task Force [44], this integrative challenge will be met by the wwPDB partners.

Highlights.

The PDB is the first, community-driven, open-access digital archive in biology.

The data in the PDB are highly curated.

The wwPDB is an international partnership that manages the archive.

The wwPDB agrees on all standardization, processing, and dissemination policies.

Storing data and methods in a standardized way supports data reproducibility.

Acknowledgments

RCSB PDB is supported by NSF [DBI-1338415], NIH, DOE; PDBe by EMBL-EBI, Wellcome Trust [104948], BBSRC [BB/J007471/1, BB/K016970/1, BB/K020013/1, BB/M013146/1, BB/M011674/1, BB/M020347/1, BB/M020428/1], NIGMS [1RO1 GM079429-01A1], EU [284209, 675858] and MRC [MR/L007835/1]; PDBj by JST-NBDC and BMRB by NIGMS [1R01 GM109046].

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bernal JD, Crowfoot DM. X-ray photographs of crystalline pepsin. Nature. 1934;133:794–795. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kendrew JC, Bodo G, Dintzis HM, Parrish RG, Wyckoff H, Phillips DC. A threedimensional model of the myoglobin molecule obtained by x-ray analysis. Nature. 1958;181:662–666. doi: 10.1038/181662a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendrew JC, Dickerson RE, Strandberg BE, Hart RG, Davies DR, Phillips DC, Shore VC. Structure of myoglobin: A three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 2 A. resolution. Nature. 1960;185:422–427. doi: 10.1038/185422a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perutz MF, Rossmann MG, Cullis AF, Muirhead H, Will G, North ACT. Structure of haemoglobin: a three-dimensional Fourier synthesis at 5.5 Å resolution, obtained by X-ray analysis. Nature. 1960;185:416–422. doi: 10.1038/185416a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bolton W, Perutz MF. Three dimensional fourier synthesis of horse deoxyhaemoglobin at 2.8 Ångstrom units resolution. Nature. 1970;228:551–552. doi: 10.1038/228551a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. Vol. 36. Cold Spring Laboratory Press; 1972. This seminal meeting highlighted the key structures that had been determined and brought together the leading figures in structural biology. To quote DAvid Phillips it was a "Coming of age."

- 7.Protein Data Bank. Protein Data Bank. Nature New Biol. 1971;233:223. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meyer EF, Jr, Morimoto CN, Villarreal J, Berman HM, Carrell HL, Stodola RK, Koetzle TF, Andrews LC, Bernstein FC, Bernstein HJ, et al. CRYSNET, a crystallographic computing network with interactive graphics display. Fed Proc. 1974;33:2402–2405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Union of Crystallography: Policy on publication and the deposition of data from crystallographic studies of biological macromolecules. Acta Cryst. 1989;A45:658. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Read RJ, Adams PD, Arendall WB, 3rd, Brunger AT, Emsley P, Joosten RP, Kleywegt GJ, Krissinel EB, Lutteke T, Otwinowski Z, et al. A new generation of crystallographic validation tools for the protein data bank. Structure. 2011;19:1395–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.08.006. This paper contained a through analysis of methods that could be used for validation of structures determined by X-ray crystallography. The recommendations were used to create the validation tools used by the wwPDB.

- 11. Henderson R, Sali A, Baker ML, Carragher B, Devkota B, Downing KH, Egelman EH, Feng Z, Frank J, Grigorieff N, et al. Outcome of the first electron microscopy validation task force meeting. Structure. 2012;20:205–214. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.12.014. This paper was the first one to analyze what is needed to validate 3DEM maps and models. It is the basis for current research in this field.

- 12. Montelione GT, Nilges M, Bax A, Guntert P, Herrmann T, Richardson JS, Schwieters CD, Vranken WF, Vuister GW, Wishart DS, et al. Recommendations of the wwPDB NMR Validation Task Force. Structure. 2013;21:1563–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.07.021. This paper made recommendations for how to validate structures determined by NMR, and is the basis for current ongoing research.

- 13. Adams PD, Aertgeerts K, Bauer C, Bell JA, Berman HM, Bhat TN, Blaney JM, Bolton E, Bricogne G, Brown D, et al. Outcome of the First wwPDB/CCDC/D3R Ligand Validation Workshop. Structure. 2016;24:502–508. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2016.02.017. The criteria for judging the quality of ligands in protein complexes are laid out and will form the basis for improved validation of these molecules.

- 14. Berman HM, Henrick K, Nakamura H. Announcing the worldwide Protein Data Bank. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:980. doi: 10.1038/nsb1203-980. This is the formal announcement for how the Protein Data Bank will be managed by an international consortium.

- 15.Brown A. J. D. Bernal: The Sage of Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lawson CL, Patwardhan A, Baker ML, Hryc C, Garcia ES, Hudson BP, Lagerstedt I, Ludtke SJ, Pintilie G, Sala R, et al. EMDataBank unified data resource for 3DEM. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D396–D403. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1126. This paper describes the procedures for streamlining the deposition and distribution of 3DEM maps and models.

- 17.Iudin A, Korir PK, Salavert-Torres J, Kleywegt GJ, Patwardhan A. EMPIAR: a public archive for raw electron microscopy image data. Nature Methods. 2016;13 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berman HM, Burley SK, Chiu W, Sali A, Adzhubei A, Bourne PE, Bryant SH, Dunbrack RL, Jr, Fidelis K, Frank J, et al. Outcome of a workshop on archiving structural models of biological macromolecules. Structure. 2006;14:1211–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.06.005. The recommendation to remove purely in silico models from the PDB is contained in this paper.

- 19.Haas J, Roth S, Arnold K, Kiefer F, Schmidt T, Bordoli L, Schwede T. The Protein Model Portal--a comprehensive resource for protein structure and model information. Database (Oxford) 2013;2013 doi: 10.1093/database/bat031. bat031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fitzgerald PMD, Westbrook JD, Bourne PE, McMahon B, Watenpaugh KD, Berman HM. 4.5 Macromolecular dictionary (mmCIF) In: Hall SR, McMahon B, editors. International Tables for Crystallography G. Definition and exchange of crystallographic data. Springer; 2005. pp. 295–443. A complete description of the mmCIF data dictionary is contained here.

- 21.Malfois M, Svergun DI. sasCIF: an extension of core Crystallographic Information File for SAS. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2000;33:812–816. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westbrook J, Ito N, Nakamura H, Henrick K, Berman HM. PDBML: the representation of archival macromolecular structure data in XML. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:988–992. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kinjo AR, Suzuki H, Yamashita R, Ikegawa Y, Kudou T, Igarashi R, Kengaku Y, Cho H, Standley DM, Nakagawa A, et al. Protein Data Bank Japan (PDBj): maintaining a structural data archive and resource description framework format. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D453–D460. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr811. Descriptions of PDBj services are given here as well as the RDF format.

- 24.Lin D, Manning NO, Jiang J, Abola EE, Stampf D, Prilusky J, Sussman JL. AutoDep: a web-based system for deposition and validation of macromolecular structural information. Acta Cryst. 2000;D56:828–841. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900005655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tagari M, Tate J, Swaminathan GJ, Newman R, Naim A, Vranken W, Kapopoulou A, Hussain A, Fillon J, Henrick K, et al. E-MSD: improving data deposition and structure quality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D287–D290. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. This is the first complete description of the services provided by the RCSB PDB.

- 27. Ulrich EL, Akutsu H, Doreleijers JF, Harano Y, Ioannidis YE, Lin J, Livny M, Mading S, Maziuk D, Miller Z, et al. BioMagResBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D402–D408. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm957. A summary of the services provided by BMRB is given here.

- 28.Drug Design Data Resource Community. [Accessed April 18 2016];Continuous Evaluation of Ligand Pose Prediction. https://drugdesigndata.org/about/celpp.

- 29.Rose PW, Prlic A, Bi C, Bluhm WF, Christie CH, Dutta S, Green RK, Goodsell DS, Westbrook JD, Woo J, et al. The RCSB Protein Data Bank: views of structural biology for basic and applied research and education. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D345–D356. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Velankar S, van Ginkel G, Alhroub Y, Battle GM, Berrisford JM, Conroy MJ, Dana JM, Gore SP, Gutmanas A, Haslam P, et al. PDBe: improved accessibility of macromolecular structure data from PDB and EMDB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D385–D395. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gutmanas A, Alhroub Y, Battle GM, Berrisford JM, Bochet E, Conroy MJ, Dana JM, Fernandez Montecelo MA, van Ginkel G, Gore SP, et al. PDBe: Protein Data Bank in Europe. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D285–D291. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1180. The services offered by PDBe are described

- 32.Kinjo AR, Nakamura H. Composite structural motifs of binding sites for delineating biological functions of proteins. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31437. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markley JL, Ulrich EL, Berman HM, Henrick K, Nakamura H, Akutsu H. BioMagResBank (BMRB) as a partner in the Worldwide Protein Data Bank (wwPDB): new policies affecting biomolecular NMR depositions. Journal of Biomolecular NMR. 2008;40:153–155. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9221-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sillitoe I, Lewis TE, Cuff A, Das S, Ashford P, Dawson NL, Furnham N, Laskowski RA, Lee D, Lees JG, et al. CATH: comprehensive structural and functional annotations for genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D376–D381. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andreeva A, Howorth D, Brenner SE, Hubbard TJ, Chothia C, Murzin AG. SCOP database in 2004: refinements integrate structure and sequence family data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D226–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andreeva A, Howorth D, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE, Hubbard TJ, Chothia C, Murzin AG. Data growth and its impact on the SCOP database: new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D419–D425. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lewis TE, Sillitoe I, Andreeva A, Blundell TL, Buchan DW, Chothia C, Cozzetto D, Dana JM, Filippis I, Gough J, et al. Genome3D: exploiting structure to help users understand their sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D382–D386. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berman HM, Olson WK, Beveridge DL, Westbrook JD, Gelbin A, Demeny T, Hsieh S-h, Srinivasan AR, Schneider B. The Nucleic Acid Database - a comprehensive relational database of three-dimensional structures of nucleic acids. Biophys. J. 1992;63:751–759. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(92)81649-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gabanyi MJ, Adams PD, Arnold K, Bordoli L, Carter LG, Flippen-Andersen J, Gifford L, Haas J, Kouranov A, McLaughlin WA, et al. The Structural Biology Knowledgebase: a portal to protein structures, sequences, functions, and methods. J Struct Funct Genomics. 2011;12:45–54. doi: 10.1007/s10969-011-9106-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madl T, Gabel F, Sattler M. NMR and small-angle scattering-based structural analysis of protein complexes in solution. J Struct Biol. 2011;173:472–482. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Z, Chernyshev A, Koehn EM, Manuel TD, Lesley SA, Kohen A. Oxidase activity of a flavin-dependent thymidylate synthase. FEBS Journal. 2009;276:2801–2810. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Byeon IJ, Louis JM, Gronenborn AM. A captured folding intermediate involved in dimerization and domain-swapping of GB1. J Mol Biol. 2004;340:615–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ward AB, Sali A, Wilson IA. Biochemistry. Integrative structural biology. Science. 2013;339:913–915. doi: 10.1126/science.1228565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sali A, Berman HM, Schwede T, Trewhella J, Kleywegt G, Burley SK, Markley J, Nakamura H, Adams P, Bonvin AM, et al. Outcome of the First wwPDB Hybrid/Integrative Methods Task Force Workshop. Structure. 2015;23:1156–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.05.013. This paper summarized the steps necessary to