Summary

The assembly of the class 5 CFA/I fimbriae of enterotoxigenic E. coli was proposed to proceed via the alternate chaperone-usher pathway. Here, we show that in the absence of the chaperone CfaA, CfaB, the major pilin subunit of CFA/I fimbriae, is able to spontaneously refold and polymerize into cyclic trimers. CfaA kinetically traps CfaB to form a metastable complex that can be stabilized by mutations. Crystal structure of the stabilized complex reveals distinctive interactions provided by CfaA to trap CfaB in an assembly competent state through donor-strand complementation and cleft-mediated anchorage. Mutagenesis indicated that donor-strand complementation controls the stability of the chaperone-subunit complex and the cleft-mediated anchorage of the subunit C-terminus additionally assist in subunit refolding. Surprisingly, over-stabilization of the chaperone-subunit complex led to delayed fimbria assembly, whereas destabilizing the complex resulted in no fimbriation. Thus, CfaA acts predominantly as a kinetic trap by stabilizing subunit to avoid its off-pathway self-polymerization that results in energetically favorable trimers and could serve as a driving force for CFA/I pilus assembly, representing an energetic landscape unique to class 5 fimbria assembly.

Keywords: Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, periplasmic chaperone, major pilin, crystal structure CfaA/B complex, self-assembly, fimbriae

Abbreviated Summary

The colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I) pili are archetypal of a group of human-specific enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) and are assembled via the alternate chaperoneusher pathway. Here, we present the structure of the chaperone CfaA in complex with subunit CfaB and demonstrate that the role of CfaA in CFA/I pilus assembly is to avoid off pathway self-polymerization of the subunit CfaB (dotted arrows).

Introduction

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is a common cause of dehydrating diarrhea, affecting millions of young children in developing countries (Savarino et al., 1998), travelers to those nations (Bolin et al., 2006) and livestock worldwide (Echeverria et al., 1978). The primary step in pathogenesis is fimbria (also called pilus)-mediated colonization of intestinal epithelium by ETEC. CFA/I (colonization factor antigen I) fimbriae, an archetype of class 5 fimbriae, are human-specific colonization factors predominantly present in many ETEC field strains (Anantha et al., 2004, Evans et al., 1979). Biogenesis of CFA/I fimbriae requires the functions of four genes (cfaA, cfaB, cfaC, and cfaE) clustered in one operon (Anantha et al., 2004). The periplasmic chaperone CfaA captures the unfolded major pilin subunit CfaB or the minor adhesive subunit CfaE, and carries those subunits in properly folded forms to the CfaC usher in the bacterial outer membrane, where the subunits polymerize into an ordered, helical pilus structure that is extruded from the bacterial surface through a process dubbed the chaperone-usher pathway (CUP) (Thanassi et al., 1998). The CUP is the predominant protein secretion mechanism dedicated to fimbria biosynthesis in Gram-negative bacteria (Nuccio & Baumler, 2007, Thanassi et al., 2005, Waksman & Hultgren, 2009).

Pilus subunits typically have an immunoglobulin-like fold (Ig-fold) with the seventh β-strand missing; the non-canonical Ig-fold is completed in trans upon insertion of the G1 donor strand from the chaperone, a process termed donor-strand complementation (DSC). Once the chaperone-stabilized subunit is brought to the usher, the chaperone G1 strand is exchanged with the N-terminal Gd strand of another subunit, a process that is called donor strand exchange (DSE) (Choudhury et al., 1999, Sauer et al., 1999). Unlike conventional chaperones that function by suppressing aggregation of protein substrates (Hartl & Hayer-Hartl, 2002), periplasmic chaperones of P-pili (PapD) and Type-1 fimbriae (FimC) additionally accelerate the folding of pilus subunits by providing missing steric information, representing a novel type of protein-folding catalyst (Bann et al., 2004, Barnhart et al., 2000) and acting as a kinetic trap to prevent self-assembly of subunits in the periplasm (Vetsch et al., 2004). Furthermore, studies on the nonpilus Caf1 fibril system suggest that by forming chaperone-subunit complexes, periplasmic chaperones also act as an energy trap, preserving subunits in a high-energy folding state (Zavialov et al., 2003, Behrens, 2003), which presumably drives subsequent assembly steps, as there is no evidence of other forms of energy input in the assembly process (Thanassi et al., 2005, Zavialov et al., 2005).

Periplasmic chaperones were classified into two groups, the FGS (F1-G1 short loop) and the FGL (F1-G1 long loop) groups based on the alignment of 26 pilus sequences (Hung et al., 1996). FGS chaperones assist in the assembly of rod-like pili, whereas FGL chaperones specifically support thin, nonpilus fibrils. Chaperones associated with the class 5 fimbra assembly (also known as the alternate chaperone-usher pathway) were recently classified into a separate group (F1-G1 alternate or FGA) based on distinctive features in the CfaA chaperone structure and sequence alignment (Bao et al., 2014), which gained support from a recent publication that shows FGA chaperones should also include those assisting assembly of archaic chaperone-usher pathway pili (Pakharukova et al., 2015). Important features that characterize the FGA chaperones are (1) a register-shifted DSC, (2) a unique D1′ insertion, and (3) a disulfide bond stabilizing C2-D1′ loop (Pakharukova et al., 2015, Bao et al., 2014). FGA chaperones also maintain the subunit in a substantially disordered conformation (Pakharukova et al., 2015). In this report, we show that the class 5 major pilin CfaB subunits refold spontaneously and self-oligomerize into thermodynamically favorable trimers. The chaperone CfaA does not appear to play a role in suppressing CfaB aggregation, rather it accelerates the refolding rate of denatured CfaB by approximately ten-fold. We found that the complex formed between native CfaA and CfaB, when purified, is unstable. Although mutations that stabilized the complex allowed its structure determination, they display a phenotype of reduced fimbriation, suggesting that the metastable chaperone-subunit complex is required for optimal fimbria assembly. Furthermore, the spontaneous formation of trimeric CfaB suggests an energetically favorable assembly path unique to the class 5 fimbriae.

Results

The native CfaA/B complex is metastable and dissociated CfaB self-oligomerizes in solution

Periplasmic chaperones serve three functions: assisting subunit refolding, suppressing their aggregation and trapping subunits in a high-energy state (Bann et al., 2004, Zavialov et al., 2003). To understand whether the class 5 CfaA chaperones function similarly, we investigated the behavior of CfaB subunits expressed in the presence or absence of CfaA. We first engineered two separate expression constructs: one for the mature wild-type CfaA (wtCfaA, from residues 1 to 219) and another for the mature form of wild-type CfaB with a hexahistidine tag at the N-terminus (wtCfaB, residues 1 to 147, Fig. 1). In this report, residues 1 to 13 are designated as the donor strand or Gd strand of subunit CfaB in order to be consistent with previous publications (Li et al., 2009a, Li et al., 2009b). Both constructs were designed to express the target proteins in the cytosol. Unexpectedly, we found that wtCfaB is highly soluble when over-expressed alone. Blue-Native PAGE (BN-PAGE) of purified wtCfaB showed the protein exists in solution as oligomers (Fig. 2A), indicating that wtCfaB can fold spontaneously and is capable of self-oligomerizing into homogeneous oligomers without help from CfaA. Out of curiosity, we purified wtCfaB and subject it to crystallization. Crystals of wtCfaB diffracted X-rays to better than 1.7 Å resolution and had the monoclinic space group symmetry of P21 (Table 1). The structure, determined by the molecular replacement method, contains two trimeric wtCfaB molecules stacked face to face. The three CfaB subunits in a trimer are arranged in a head-to-tail configuration with each wtCfaB contributing a donor strand (Gd) to complete in trans the Ig-fold of a foregoing subunit (Fig. 3A and Fig S1). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first structure of in trans donor-strand exchanged wild-type pilin subunit formed in the absence of chaperone. More interestingly, the three-residue linker (residues V11D12P13) immediately following the Gd strand bends roughly 120° for trimer formation, as compared to the 180° angle for the linker in the in cis dscCfaBBB structure (Fig. S1B, PDB code: 3F85) (Li et al., 2009a). Thus, wtCfaB is capable of self-polymerizing into a stable, in trans donor-strand exchanged trimer in the absence of the periplasmic CfaA chaperone.

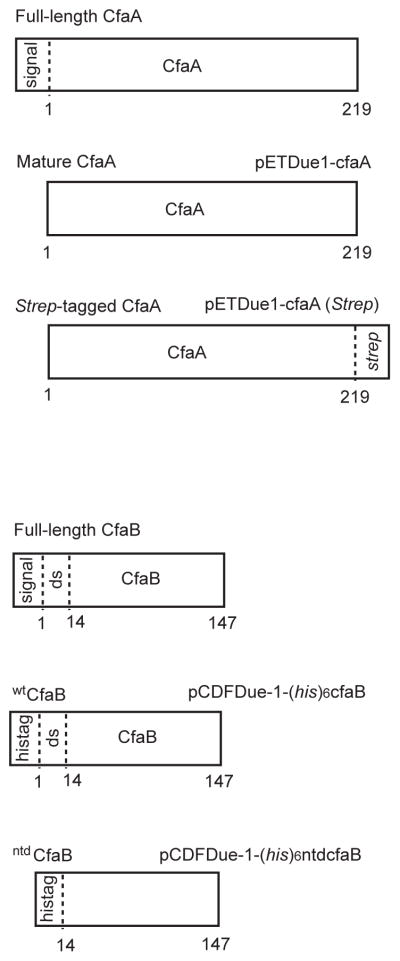

Figure 1. Expression constructs for expressing chaperone CfaA and subunit CfaB in the cytosol.

Following the conventions in the literature, the full-length CfaA and CfaB start at residue number 1, excluding signal peptides. The signal peptide for the CfaA is 19 residues and that for the CfaB is 23. In the CfaB constructs, the donor-strand is denoted as ds and the N-terminal deletion is denoted as ntd.

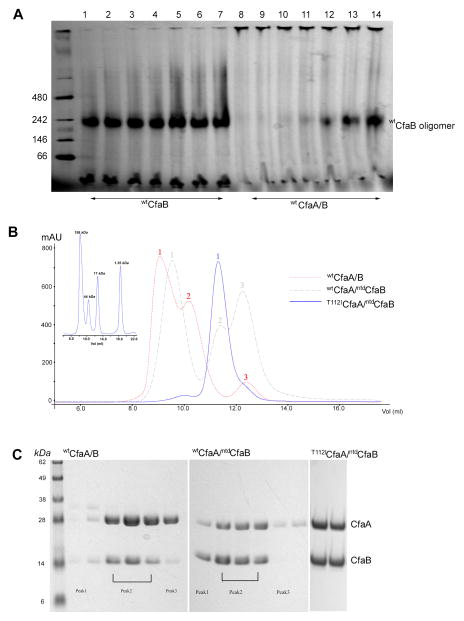

Figure 2. Stability of purified CfaA/B hetero-dimer.

(A) Blue Native (BN)-PAGE analysis of wtCfaA/B complex. Lanes 1–7 are purified wtCfaB that was expressed in the absence of CfaA and incubated at 37°C for 0, 10, 30, 60, 180, 360, and 540 minutes, respectively. CfaB subunits form oligomers that run at an apparent molecular weight of 200 kDa. Lanes 8–14 are freshly purified wtCfaA/B complex that was incubated at 37°C for the same lengths of time. Neither the CfaA/B complex nor CfaA alone runs into gel. (B) Size-exclusion chromatographic (SEC, Superdex 75) profiles of wild-type and variant CfaA/B complexes. The wtCfaA/B complex (red) displays three peaks. Peaks 1 and 2 are complexes of wtCfaA/B with wtCfaB in various polymerization states or oligomeric CfaB and peak 3 is wtCfaA. No peak represents a stable wtCfaA/B complex. The profile for the molecular weight standards under the same conditions is given on the left (inset). Removing the N-terminal donor peptide of CfaB helps to stabilize the complex (wtCfaA/ntdCfaB, gray), which also display 3 peaks in SEC profile. Peak 2 shows stabilized complex in solution. Introducing the T112I mutation to wtCfaA together with the ntdCfaB led to stabilization of the T112ICfaA/ntdCfaB complex in solution (blue). (C) SDS-PAGE analysis of SEC peaks in (B). The left panel shows protein components contained in peaks 1, 2, and 3 for the red line in (B) in various stoichiometric ratios such as CfaA, CfaA/B, CfaA/B2, CfaA/B3 or (CfaB)3. The middle panel is for the gray line in (B), showing a more uniform stoichiometric ratio between CfaA and CfaB. The right panel shows the peak in the blue line in (B) with CfaA and CfaB in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio.

Table 1.

Statistics on qualities of diffraction data sets and atomic models of wtCfaB trimer and CfaA/B complex

| Data Set | wtCfaB (cytoplasmic expressed) | wtCfaB (from native wtCfaA/B complex) | T112ICfaA/ntdCfaB complex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.98197 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Space group | P21 | P321 | R3 (Hexagonal setting) |

| Unit cell (Å,°) |

a = 66.3, b = 105.8, c = 70.1 β = 114.05 |

a = b = 114.7, c = 67.081 | a = b = 129.2, c = 73.3 |

| Resolution (outer shell) (Å) | 40.78–1.75 (1.82–1.75)a | 40–2.40 (2.49–2.40)a | 50–2.32 (2.40–2.32)a |

| No. unique reflections | 85,281 (8,101) | 19,692 (1,877) | 18,960 (1,412) |

| Rmerge | 0.12 (0.527) | 0.073 (0.425) | 0.079 (0.474) |

| Completeness | 96.4 (91.6) | 97.3 (93.2) | 96.4 (72.2) |

| Redundancy | 3.3 (2.3) | 4.6 (2.9) | 7.5 (2.3) |

| I/σ | 8.3 (1.54) | 14.4 (2.02) | 20.0 (1.0) |

| Model refinement | |||

| Rwork (%) | 20.36 (34.44) | 23.73 (32.5)b | 23.56 (30.06) |

| Rfree (%)c | 23.96 (36.79) | 26.03 (35.4) | 26.23 (31.44) |

| No. of protein atoms (no-hydrogen) | 6,500 | 3,203 | 2,733 |

| No. of non-protein atoms | 653 | 167 | 161 |

| Average B-factor (Å2) | 20.5 | 55.2 | 79.4 |

| Rmsd for bond lengths (Å) | 0.015 | 0.013 | 0.017 |

| Rmsd for bond angles (°) | 1.56 | 1.56 | 1.35 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |||

| Favored | 99.7 | 94 | 95 |

| allowed | 0.3 | 6 | 5 |

| Disallowed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

numbers in parentheses are statistics of the outer shell.

The crystal is merohedrally twined with a twin fraction of 0.81.

5% of total reflections were set aside for the Rfree calculation

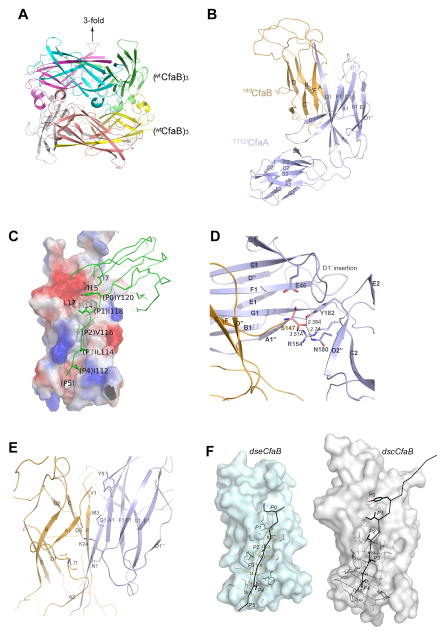

Figure 3. Structure of hexameric dseCfaB and T112ICfaA/ntdCfaB complex.

(A) Ribbon representation of the structure of two face-to-face stacked trimeric, donor-strand exchanged dseCfaB complexes. Each monomer is represented in a unique color. The 3-fold axis for the subunits of the trimer is indicated. (B) Ribbon diagram of the T112ICfaA/ntdCfaB complex structure. The chaperone CfaA is represented in violet and the bound, in trans donor-strand complemented subunit dscCfaB is in gold. Each β-strand is labeled according to the previous publications (Li et al., 2009a, Bao et al., 2014). (C) Interaction of CfaB with CfaA in the vicinity of the hydrophobic groove of CfaB. Subunit dscCfaB lacking the donor strand is shown as an electrostatic potential surface with positive potential in blue and negative potential in red. The chaperone CfaA is shown as the Cα trace in green and hydrophobic residues on the donor strand (G1 strand) are depicted as stick models with carbon atoms in green, nitrogen in blue and oxygen in red. Hydrophobic pockets in the groove of dscCfaB are labeled P0 to P5 into which donor strand residues fit. (D) Specific interactions of FGA chaperone CfaA in anchoring the C-terminus of the subunit dscCfaB. The C-terminus of the subunit CfaB (gold), in cartoon representation, penetrates deep into the cleft of chaperone CfaA (violet), where it is anchored by four specific FGA residues, E46, R154, N180 and Y182 shown in stick models. Distances from these residues to the C-terminal oxygen atoms are indicated. (E) Ribbon diagram showing specific interactions of CfaA N-terminal A1′ strand (violet) with residues in the A and F strands of the dscCfaB (gold). Conserved FGA chaperone residues M3, Y5 and K24 are shown as stick models, which participate in interactions with CfaB. (F) Comparison of dscCfaB and dseCfaB. Molecular surface of dseCfaB (left, cyan) and dscCfaB (right, gray) are given in the absence of bound donor strands, which are shown as stick models in black. Residues in stick models in the A and F β-strands that flank the hydrophobic groove are also shown embedded. Hydrophobic pockets P0 to P5 are labeled and equivalent distances across each hydrophobic pocket are given for both dseCfaB and dscCfaB.

Cytosolic expression of wtCfaB in the presence of wtCfaA led to the formation of the wtCfaA/B complex, as evidenced by the purified complex based on tandem Ni-NTA and Strep-Tactin affinity purification of hexahistidine-tagged wtCfaB and Strep-tagged CfaA (Bao et al., 2014). However, the purified complex showed three peaks in a size-exclusion chromatographic (SEC) profile, suggesting the wtCfaA/B complex is unstable, readily dissociating in solution (Figs. 2B and 2C). To test its stability, freshly purified wtCfaA/B complex was incubated at 37 °C for various periods of time and followed by BN-PAGE analysis (Fig. 2A). In approximately 60 minutes, evidence of dissociation of CfaB from the complex began to emerge and stable oligomers of wtCfaB could be detected.

In hopes of determining the wtCfaA/B complex structure, we subjected freshly prepared complex to crystallization trials. Crystals appeared over a month post the crystallization experiment. Diffraction experiments showed the crystals belong to the trigonal space group P321. Disappointingly, the final structure showed that only wtCfaB was present in the crystals, forming stacked double wtCfaB trimers identical to those in crystals obtained with purified wtCfaB (Fig. 3A, Table 1). These experiments demonstrated that not only is trimeric wtCfaB thermodynamically more stable than the wtCfaA/B complex, but wtCfaA appears neither necessary for wtCfaB folding nor required for suppressing its aggregation, contradicting the classic definition of a chaperone (Hartl & Hayer-Hartl, 2002). This observation of a meta-stable wtCfaA/B complex led us to postulate that one function of the CfaA chaperone is to transiently trap subunits in an assembly-competent state, effectively delaying the process of their self-oligomerization in solution.

CfaA assists refolding of denatured CfaB and transiently stabilizes folded CfaB

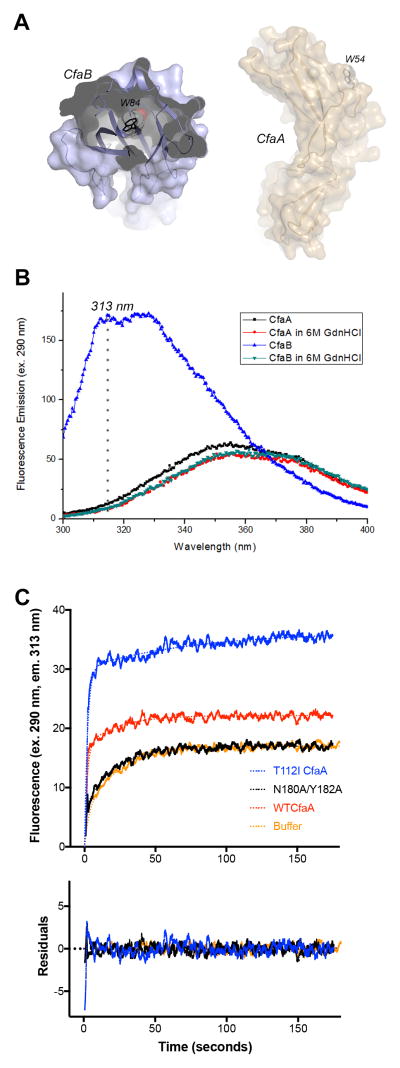

To investigate the role of CfaA in pilus biogenesis in more detail, we looked at the folding kinetics of subunit CfaB in the presence or absence of chaperone CfaA by following the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence in CfaB. There is one tryptophan residue each in CfaA (W54) and CfaB (W84); W54 of CfaA is exposed to the solvent, whereas W84 of CfaB is buried in the protein hydrophobic core, as shown in their respective crystal structures (Fig. 4A) (Li et al., 2009a, Bao et al., 2014). Thus, the tryptophan residue in the latter is potentially useful for monitoring subunit refolding. Indeed, the equilibrium emission spectrum of CfaA in the presence or absence of 5 M guanidinium chloride (GdnHCl) is quite similar, whereas the presence of the GdnHCl has a dramatic effect on the spectrum of CfaB (Fig. 4B). Although the fluorescence emission for the native CfaB peaks at 320 nm, we used the intensity at 313 nm for measurements because of the negligible difference in fluorescence spectra contributed by folded and unfolded CfaA at that wavelength.

Figure 4. CfaA stabilizes CfaB in an assembly-competent conformation.

(A) A cut-away surface of subunit CfaB structure (left) and the surface of the chaperone CfaA demonstrate that the only tryptophan residue for the subunit CfaB, W84, is buried in the hydrophobic core of the protein, whereas that for CfaA, W54, is exposed to the solvent. (B) Equilibrium fluorescence emission spectra of CfaB and CfaA in the presence or absence of 5 M GdnHCl. Spectrum was recorded with a solution containing either 3.3 μM of CfaB or 7.2 μM of CfaA, native in PBS or denatured in 5 M GdnHCl, with excitation wavelength at 290 nm. Fluorescence emission was recorded over the wavelength range from 300 nm to 400 nm. (C) Fluorescence kinetics of refolding of denatured CfaB in the absence or presence of CfaA variants. CfaB denatured in 5 M GdnHCl was rapidly diluted 35-fold to a final concentration of 2.5 μM in the absence or presence of 7.2 μM of CfaA variants and time-dependent tryptophan fluorescence emission at 313 nm was followed over a period of 180 seconds.

Upon a rapid 35-fold dilution of CfaB denatured in 5 M GdnHCl into a PBS (phosphate buffered saline) solution, a time-dependent increase in fluorescence intensity was observed (Fig. 4C), illustrating the ability of CfaB to refold spontaneously. This time-dependent fluorescence of CfaB refolding kinetic curve can be fitted to either a single-exponential growth function with a rate constant (k) of 0.064 s−1 or a double-exponential growth model with a k of 0.043 s−1 (Table 2). Although the fitting of the latter model is only marginally better, it nevertheless illustrates the presence of a fast phase in the refolding kinetics. However, in the presence of wild-type chaperone wtCfaA, the kinetics of CfaB refolding could be fitted only to a double-exponential function, giving rise to a slow rate constant (ks) of 0.046 s−1, which is similar to the spontaneous refolding rate, and an estimated fast rate constant (kf) of 0.54 s−1. Thus, the slow phase can be attributed to the spontaneous refolding of CfaB, whereas the fast phase is a result of chaperone-assisted CfaB refolding. The relative contributions of these two processes to the overall fluorescence intensity (I∞) are estimated as %fI∞ and %sI∞, respectively, for the fast and slow phases and the ratio, %fI∞/%sI∞, is designated as the contribution ratio. For wild-type CfaA, the contribution ratio is approximately 3 (Table 2). It was noticed that the addition of wtCfaA increased the total fluorescence intensity (I∞), which is also chaperone-concentration-dependent (data not shown). This increased I∞ is not due to CfaA fluorescence and is an indication that CfaA stabilizes the folded subunit. Similar phenomena were reported previously in PapD-assisted PapE refolding (Bann et al., 2004).

Table 2.

Fitting of a double-exponential model for the refolding of CfaB in the presence or absence of CfaA variantsa

| CfaA variant | Max Intensity I∞ | Slow Phase | Fast Phase | Contribution Ratio (%fI∞/%sI∞) | Adjusted R2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| %sI∞ | ks(s−1) | %fI∞ | kf(s−1) | ||||

| -CfaA | 17.4±0.5b | 100 | 0.064±0.003 | - | - | - | 0.916 |

| (17.6±0.5)c | (68) | (0.043±0.006) | (32±4) | -d | (0.47) | (0.962) | |

|

| |||||||

| wtCfaA | 21.6±0.5 | 25 | 0.046±0.007 | 75±4 | 0.54±0.07 | 3 | 0.878 |

|

| |||||||

| T112ICfaAe | 37.3±0.9 | 6 | - d | 94±9 | 0.42±0.07 | 15.7 | 0.908 |

|

| |||||||

| T112I/L114I/V116ICfaA | 36.5±2.3 | - | - | 100 | 0.46±0.07 | - | 0.872 |

|

| |||||||

| L114A/V116ACfaA | 19.0±0.4 | 55 | 0.045±0.002 | 45±4 | 1.54±0.70 | 0.82 | 0.946 |

|

| |||||||

| N180ACfaA | 20.5±0.1 | 37 | 0.058±0.002 | 63±1 | 0.86±0.42 | 1.70 | 0.944 |

|

| |||||||

| Y182ACfaA | 18.0±0.4 | 59 | 0.054±0.005 | 41±5 | 0.85±0.40 | 0.69 | 0.951 |

|

| |||||||

| R154ACfaA | 23.9±1.9 | 30 | 0.034±0.003 | 70±2 | 0.41±0.03 | 2.33 | 0.943 |

|

| |||||||

| N180A/Y182ACfaA | 16.3±0.9 | 63 | 0.051±0.003 | 37±3 | 0.77±0.19 | 0.59 | 0.958 |

|

| |||||||

| N180A/Y182A/R154ACfaA | 18.6±0.1 | 55 | 0.054±0.011 | 45±3 | 0.76±0.08 | 0.82 | 0.953 |

All parameters were obtained by fitting the equation I(t) = I∞ − %fI∞* exp (−kf*t) − %sI∞l*exp(−ks*t) to a data set and averaged over three independent experiments.

Data fitted to a single-phased model.

Data fitted to a double-phased model. The Kf values for the fast phase are estimates.

Parameter too varied to be determined.

These mutants have very low contributions from the slow phase.

Stabilization of the CfaA/B complex

To elucidate by crystallography how chaperone CfaA interacts with CfaB at atomic resolution, the complex must be stabilized. One possible cause for the observed metastability of the complex is the presence of an N-terminal flexible donor strand (Gd strand from residues 1 to 13) in wtCfaB, which is predicted to provide the driving force for shifting the equilibrium towards trimeric wtCfaB formation. This possibility was manifested in chaperone-subunit structures of two FGL (Caf1M and SafB) and three FGS (FimC, PapD and FaeE) chaperones, where deletion of the N-terminal extension (nte) in the major subunits prevented self-polymerization (Remaut et al., 2006, Crespo et al., 2012, Verger et al., 2007, Van Molle et al., 2009, Zavialov et al., 2003). Thus, we engineered an N-terminal donor-strand deleted CfaB construct (ntdCfaB, Fig. 1). Purified ntdCfaB stabilized the complex to a certain degree but was insufficient to form a stable complex for crystallographic analysis (Figs. 2B and 2C).

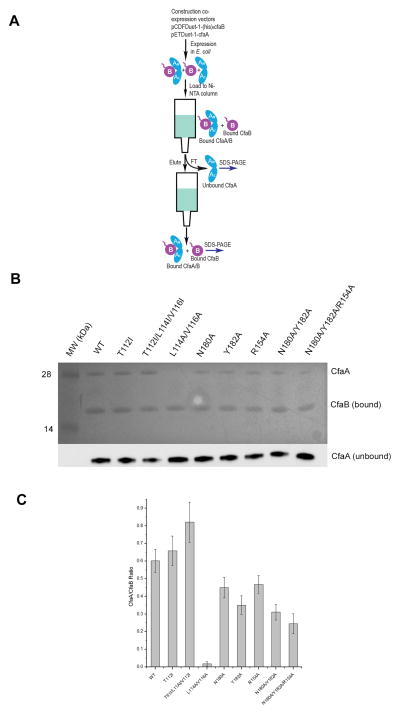

We have shown previously, based on the CfaA structure, that an alanine substitution for residue T112 in the chaperone G1 strand substantially impacted CFA/I piliation (Bao et al., 2014) and T112 was predicted to insert into the P4 pocket of the subunit’s hydrophobic groove. To further enhance the chaperone subunit interaction, we introduced a single mutation (T112I) to CfaA (T112ICfaA) and the resulting T112ICfaA/ntdCfaB complex displayed superior stability in solution, as demonstrated by the SEC elution profile (Fig. 2B and 2C), eliminating self-oligomerized CfaB. We also made a triple-mutation T112I/L114I/V116ICfaA that behaved similarly in SEC experiments (data not shown). To visualize directly the subunit binding efficiency of CfaA for both wild type and mutants, we employed a pull-down assay that allowed estimation of the ratio between CfaA and CfaB in their complex (Bao et al., 2014) (Fig. 5A). Both T112ICfaA and T112I/L114I/V116ICfaA mutants showed enhanced binding to CfaB, compared to wild-type CfaA (Figs 2B, 5B and 5C). The ratio between CfaA and CfaB determined by densitometry analysis of the pull-down assay showed an increase from wild type of 0.60 to 0.66 and 0.82, respectively, for the T112I and T112I/L114I/V116I mutants.

Figure 5. Mutational analysis of CfaA in subunit stabilization.

(A) Schematic description of the procedure for preparing CfaA/B complex. (B) SDS-PAGE of eluted fractions from the Ni-NTA column pull-down assay for wtCfaA/B complex and complexes with various CfaA mutants. Unbound CfaA in flow-through fractions were detected by immunoblot with a specific antibody. (C) Results of densitometry analysis of bands in (B) to obtain the ratio between CfaA variant and bound CfaB. Error bars indicate standard deviations derived from four independent experiments.

We tested the ability of T112ICfaA and T112I/L114I/V116ICfaA to assist the refolding of denatured CfaB. Both mutants increased the total fluorescence intensity (I∞) by more than 100%, in which nearly all I∞ was contributed by the chaperone-assisted fast phase process (Table 2). Since the rate constants for the fast phase remain unchanged for these mutants, when compared to the wild type, it suggests that the CfaA G1 strand is important for the stability of the CfaA/B complex. In neither case was the rate constant of the slow phase measured accurately, due to their very small contributions (Table 2). Taking together, CfaA mutants T112I and T112I/L114I/V116I offer enhanced stability to the CfaA/B complex, which is consistent with the notion that T112 in the G1 strand acts as a P4 pocket-interacting residue.

Crystal structure of the T112ICfaA/ntdCfaB complex reveals distinctive features in chaperone-subunit interactions

The stabilized T112ICfaA/ntdCfaB complex was crystallized and the structure of the complex was determined to 2.32 Å resolution (Table 1). Like structures of most chaperone-subunit complexes determined to date, a large cleft between the two Ig-like domains of CfaA accommodates CfaB via a typical DSC mechanism such that residues (111–122) in the G1-F1 loop from CfaA become part of the G1 β-strand that is inserted into the hydrophobic groove between the A and F strands of CfaB (Fig. 3B). In CfaA and related FGA chaperones, the number of hydrophobic residues donated to compensate for the missing Gd strand is four (Y120, I118, V116 and L114), as compared to three in FGS and five in FGL chaperones. The N-terminal domain of CfaA provides much of the interaction (1,450.7 Å2 of buried surface area) for subunit binding as compared to the C-terminal domain (169.3 Å2 of buried surface area). As was previously speculated (Bao et al., 2014), CfaA does not undergo major domain movement upon CfaB binding; the root-mean-square deviation (rms deviation) is 0.88 Å for 197 superimposed Cα atoms out of 210 residues between the apo and the CfaB bound forms and the largest contributor to the rms deviation comes from the donor strand (residues 102–110), which is highly flexible and disordered in the apoCfaA structure. Two other structural elements contribute significantly to the rms deviation: One is the D1′ loop, which is a feature unique to the FGA chaperones and includes the D1′ insertion (residues 41–56) of the chaperone N-terminal domain (Bao et al., 2014) (Fig. S2). The other is in the C-terminal domain between residues 139–145 (A2-B2 loop) (Fig. S2). The latter region is not in direct contact with the bound subunit.

Interactions between the chaperone and subunit are limited, mainly in two areas of the subunit: one is the hydrophobic groove that accepts the G1 donor strand and another is at its C-terminus for chaperone anchorage. Consistent with chaperone-subunit complex structures of other fimbrial systems, the three hydrophobic residues (L114, V116 and I118) of the CfaA G1 strand are deeply buried in the P3, P2 and P1 pockets in the hydrophobic groove of CfaB, respectively (Fig. 3C). Despite weak electron density, the P4 pocket is occupied by residue I112, which was mutated from a threonine in the wild-type CfaA; this is in agreement with our observations that the T112I mutation stabilizes the complex in solution (Figs. 2B and 2C) and this position is important to CFA/I pilus assembly (Bao et al., 2014). The weaker density for I112 in the complex, however, suggests that the threonine residue of wild-type CfaA at this position could be in constant transition between bound and unbound states, and thus is poised to undergo a subsequent DSE step via the zip-in-zip-out process (Zavialov et al., 2003).

Consistent with the recently published complex structures of EcpA/B of E. coli common pili and CsuA/B of archaic Csu pili ucture (Pakharukova et al., 2015), there exists a P0 hydrophobic pocket in CfaB demarcated by residues I15, L17 and M143 (Fig. 3C). The presence of the P0 position for FGA chaperones was suggested previously, based on structure alignment of chaperones, in order to accommodate residue Y120 in the G1 donor strand of CfaA (Bao et al., 2014). Eliminating this interaction by alanine substitution of Y120 caused dramatically decreased subunit-chaperone interaction and piliation failure. The complex structure further revealed an additional shallower hydrophobic depression near the P0 site, which is occupied by the hydrophobic residue I7 in the A1 strand of CfaA (Fig. 3C), contributing to the interaction between chaperone and subunit.

A second area of conserved interactions found in all reported FGL and FGS chaperone-subunit complexes involves the carboxyl-terminus of the subunit that penetrates deep into the inter-domain cleft of the chaperone and is anchored by two conserved basic residues: an arginine residue (R8 in PapD) in the A1 strand and a lysine residue (K112 in PapD) in the adjacent G1 strand (Kuehn et al., 1993, Soto et al., 1998, Sauer et al., 2004). For CfaA and related FGA chaperones, it was suggested that the subunit-anchoring function should be carried out by a set of FGA chaperone-specific residues including R154 in the B2-C2 loop (Bao et al., 2014). Indeed, the complex structure confirmed the direct involvement of residue R154 in anchoring the C-terminus of CfaB and additionally identifies two more conserved residues in the FGA family, located on the D2″ β-strand of CfaA, N180 and Y182, to form close contacts with the C-terminus of the subunit (Fig. 3D). In fact, among the three C-terminus interacting residues, Y182 is the closest, with a distance of 2.38 Å. Moreover, residue E46, conserved only in FGA chaperones, is within H-bonding distance (2.67 Å) to the side chain of the terminal residue S147.

Probing the role of CfaA in subunit refolding and stabilization by mutagenesis

We have shown that CfaA serves the functions of assisting CfaB refolding and providing subunit stabilization in an assembly-competent manner. So, how do the two major areas of interactions revealed by the structure of CfaA/B complex serve to mediate these functions? We sought to address these questions by introducing alanine substitutions to residues in the areas that interact with CfaB. One area is in the G1 strand (L114A/V116A) and another in the chaperone cleft region (R154A, N180A, Y182A, N180A/Y182A and N180A/Y182A/R154A) (Table 3). A mutation designed to reduce chaperone-subunit interaction in the G1 strand (L114A/V116A) nearly eliminated CfaA binding to CfaB (97% reduction) in a pull-down assay (Fig. 5). Although the time trace of fluorescence intensity of the subunit refolding experiment still fits the double-exponential function, this mutant is no longer able to provide the same stability to folded subunits as the wild type, because the I∞ is only slightly higher than that of no chaperone added. However, it was apparently still able to catalyze chaperone-assisted subunit refolding with a three-fold increased fast-phase rate constant (1.54 s−1, Table 2), compared to the wild type. Together with the two mutations in the G1 strand (T112I and T112I/L114I), it is clear that the chaperone G1 donor strand controls the stability of the chaperone-subunit complex.

Table 3.

Effects of CfaA mutations on its interaction with CfaB and pilus formation.

| Mutation | Location | Subunit bindinga | Fimbriation | Possible defect in function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T112I | G1 strand | Tighter binding | delayedb | P4: DSE deficient | This work |

| T112A | G1 strand | No effect | No fimbriationc | P4: DSE | Bao et al. 2014 |

| T112I/L114I/V116I | G1 strand | Slightly reduced | No effectb | This work | |

| L114A | G1 strand | Dramatically reduced | No effectc | P3: subunit binding | Bao et al. 2014 |

| L114A/V116A | G1 strand | Lost | No fimbriationb | This work | |

| L116A | G1 Strand | Lost | Delayer considerablyc | P2: subunit binding | Bao et al. 2014 |

| I118A | G1 strand | Lost | Delayedc | P1: subunit binding | Bao et al. 2014 |

| Y120A | G1 strand | Lost | No fimbriationc | P0: subunit binding | Bao et al. 2014 |

| K9A | A1″ strand | No effect | Delayedc | Replaced by R154 | Bao et al. 2014 |

| R125A | G1 strand | No effect | Delayed considerablyc | Interaction with usher | Bao et al. 2014 |

| R154A | C2 strand | Reduced | No effectc | Replace K9 for subunit interaction | Bao et al. 2014 |

| R154A | C2 strand | Reduced | No effectb | Replace K9 for subunit interaction | This work |

| N180A | D2″ strand | Reduced | delayedb | Subunit anchoring | This work |

| Y182A | Between D2″ and E2 | Reduced | Delayed b | Subunit anchoring | This work |

| N180A/Y182A | Near D2″ strand | Reduced | Delayedb | Subunit anchoring | This work |

| N180A/Y182A/R154A | Reduced | No fimbriationb | Subunit anchoring | This work |

Subunit binding was measured by pull-down assay.

Fimbriation was assayed by time-resolved bact-ELISA.

Fimbriation was assayed by time-resolved MRHA.

Mutations in the cleft region of CfaA (N180A, Y182A, R154A, N180A/Y182A, and N180A/Y182A/R154A) were predicted to interfere with its interaction with the C-terminus of CfaB and, indeed, caused a reduction in the CfaA/CfaB ratio from 0.6 for the wild type to a number between 0.24 and 0.48 for the mutants in a pull-down assay (Fig. 5), which was consistent with our structural analysis of CfaA-CfaB interactions. As expected, the largest reduction for a single mutation was observed for the Y182A mutant, because this residue has the shortest distance to the C-terminus of CfaB and thus provides the strongest interaction with one of the carboxylate oxygen atoms. Any mutant containing the Y182A mutation (Y182A, N180A/Y182A and N180A/Y182A/R154A) exhibits a profoundly negative effect on both chaperone-assisted CfaB refolding and CfaA/B complex stability, with the total fluorescence intensity I∞ reduced to the level of spontaneous CfaB refolding. Concomitantly, the contribution ratios for these three mutants are among the lowest in all mutants tested (Table 2), even though the fast rate constants (kf) are about the same as or higher than that of wild type. The other two cleft residues N180 and R154 are farther away from the C-terminus (2.70 Å and 3.51 Å, respectively) and their mutations (N180A or R154A) showed only a small effect on the total fluorescence intensity I∞ of folded CfaB but had a mixed effect on the chaperone-assisted folding rate. While the N180A mutant has a higher rate (kf=0.86 s−1) than the wild type (kf=0.54 s−1), the rate for the R154A mutant is lower (kf=0.41 s−1). Thus, interactions between the subunit C-terminus and the cleft region of the chaperone play a major role in both chaperone-assisted CfaB folding and its subsequent stabilization.

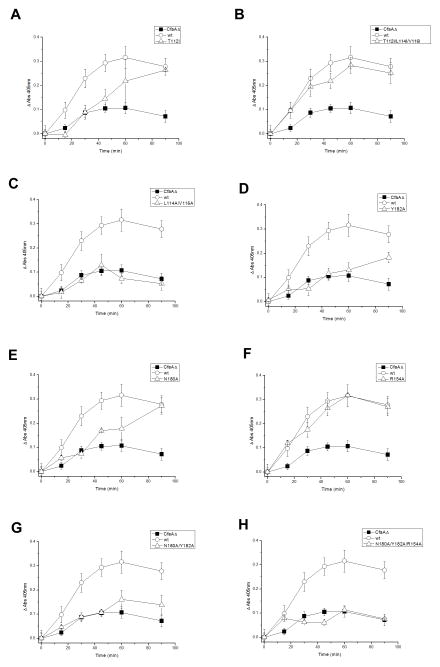

Effect of CfaA mutations on pilus assembly

To assess how changes in chaperone-subunit interactions affect the pilus assembly in vivo, we adopted a whole-bacterial cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (bact-ELISA) (Prieto et al., 2003) to measure the effect of CfaA mutations on the CFA/I pilus formation or piliation at various time intervals after induction of protein expression, which we termed time-resolved bact-ELISA. First, mutants of the donor strand were tested. Mutants that enhanced chaperone-subunit interactions in the G1 strand exhibited a phenotype of delayed pilus assembly, compared to the wild type (Figs. 6A and 6B), whereas a mutation (L114A/V116A) that prevented CfaA binding to CfaB resulted in no piliation (Fig. 6C). Considering that the DSE is a complicated multi-component process and perhaps the rate-limiting step in pilus assembly, our result suggests that for DSE to proceed efficiently, there must be an optimal CfaA/B complex dissociation rate that needs to be compatible with the rate of DSE. Thus, CfaA mutants that stabilize the complex are slower in releasing subunit CfaB, leading to a decrease in the pilus assembly rate.

Figure 6. Effects of CfaA mutations on CFA/I piliation.

CFA/I pili expressed on the surface were detected by bact-ELISA using a specific antibody against subunit CfaB at pre-defined time intervals after the induction of CFA/I operon that contains CfaA variants. The wild-type CfaA was used as a positive control and a CfaA knock-out strain was used as a negative control. (A) T112I (B) T112I/L114I/V116I (C) L114A/V116A (D) Y182A (E) N180A (F) R154A (G) N180A/Y182A (H) N180A/Y182A/R154A

Although the underlying mechanism may be different, mutations that break the interaction with C-terminus of CfaB also lead to reduced surface piliation. For example, mutants that contain Y182A suffer severe consequences, with significant loss of piliation (Figs. 6D, 6G and 6H). The effect of additional mutations is additive, as shown in mutants N180A/Y182A and N180A/Y182A/R154A, with the latter having a complete loss of fimbriation. Both R154A and N180A mutants showed a delay in pilus assembly; the N180A mutation had more impact on piliation than R154A because it has a lower contribution ratio than R154A (Table 2), which is in accordance with the fact that N180 is closer than R154 to the last residue of CfaB.

Discussion

The role of CfaA in CFA/I assembly

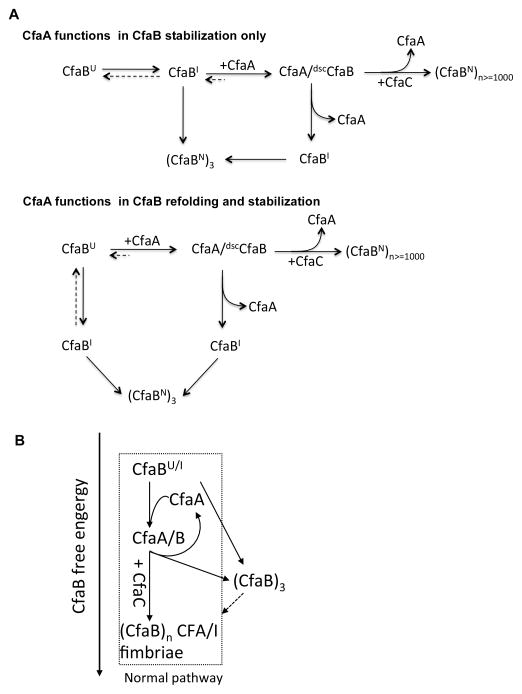

Previous studies on FGS and FGL family chaperones resulted in extensive knowledge concerning their functions and the prevention of substrate aggregation is a fundamental activity for most chaperones (Bann et al., 2004, Barnhart et al., 2000, Vetsch et al., 2004). However, the classic role of periplasmic chaperones in preventing subunit aggregation was questioned by reports showing that some subunits tend to dissociate from the chaperone-subunit complex and undergo spontaneous polymerization into ordered structures instead of forming insoluble aggregates (Verger et al., 2007, Puorger et al., 2011, Zavialov et al., 2002). Further deviating from the functions of classic chaperones, periplasmic chaperones were shown to also promote subunit refolding in vitro by up to 400-fold (Puorger et al., 2011), which mimics the process of chaperone-assisted refolding of subunits in the periplasm. In this work, we demonstrated that the FGA family chaperone CfaA does not play a significant role in preventing CfaB aggregation because subunit CfaB is able to fold spontaneously both in vivo and in vitro and remains soluble as in trans donor-strand complemented trimers in solution. We showed that CfaA is able to assist chemically denatured subunit CfaB refolding, although the rate of acceleration is a moderate ten-fold (Table 2). Like many other chaperone-subunit complexes, the wild-type CfaA/B complex undergoes spontaneous, non-reversible dissociation, indicating that CfaA only transiently stabilizes the CfaB subunit in a high-energy folding state, functioning as a kinetic trap to slow down the rate of spontaneous self-assembly of CfaB subunits. This conclusion was supported by our experimental attempts to stabilize the CfaA/B complex, which resulted in a significant delay in pilus formation (Fig. 6).

Our kinetic experiments clearly distinguish the two possible mechanisms for CfaA function: one in which CfaA involves subunit stabilization only and the other it participates in both subunit refolding and subsequent stabilization (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, our work also suggests that the mechanism for pilus assembly has evolved to strike a delicate balance between the stability of the CfaA/B complex and the rate of the DSE reaction for subunit polymerization (Fig. 7A). Such a balance appears to include the decoupling of the process of subunit refolding from that of pilus assembly (Bao et al., 2014) and a meta-stable chaperone-subunit complex. The hallmark of this balance is the relative insensitivity of pilus assembly to potential defects in many of the intermediate steps leading to pilus biogenesis. For example, a number of single mutations listed in Table 3 altered significantly the binding of CfaA to CfaB, yet the effect on bacterial piliation shown in in vivo assays was mitigated. Nevertheless, over-stabilization of the CfaA/B complex leads to a delay in surface piliation, and destabilization can cause no piliation due to premature subunit dissociation and spontaneous subunit polymerization in the periplasm. Our refolding kinetic and in vivo piliation data suggest that control over the chaperone-subunit stability is provided by the chaperone G1 donor strand and the cluster of residues, especially Y182, responsible for anchoring the subunit C-terminus is important for both chaperone-assisted subunit refolding and stabilization.

Figure 7. Subunit CfaB folding pathways, the energy landscape of CFA/I assembly and the proposed function of chaperone CfaA.

(A) Function of CfaA. The assembly of CFA/I fimbriae starts with the transport of subunit CfaB into the periplasm (CfaBU), where it refolds either spontaneously into some forms of folding intermediates (CfaBI) or is assisted by CfaA to form dscCfaB. Spontaneously, CfaBI, while in equilibration with CfaBU, self-assembles into a stable trimeric native CfaB (CfaBN)3 in solution. Our kinetic data eliminated the possibility that CfaA functions to stabilize CfaB only. The dscCfaB, assisted in folding by CfaA, forms a metastable CfaA/dscCfaB complex, which is required for CFA/I pilus assembly under the direction of the usher CfaC (CfaBN)n>=1000. The metastable CfaA/dscCfaB complex also undergoes a spontaneous dissociation to form donor-strand exchanged CfaA/B2, CfaA/B3 and (CfaB)3. (B) CfaB free energy landscape from folding to assembly. CfaBU/I have the highest free energy and native CFA/I fimbria has the lowest free energy because of lateral interactions between CfaB subunits, whereas the off-pathway trimerized (CfaB)3 lacks that interaction. The dashed line is the process that has not been observed in our experiment.

Structure of the CfaA/B complex reveals potential functions of FGA chaperone-specific regions

In addition to the P0 pocket-interacting residue Y120 in the chaperone G1 strand and to the unique set of subunit anchoring residues (R154, N180 and Y182), FGA chaperones feature a number of other characteristic sequence insertions compared to the FGS and FGL chaperones. Mutations introduced into these regions led to functional defects in pilus assembly (Bao et al., 2014). Conceivably, these features may provide interactions with the major subunit CfaB, minor subunit CfaE, or the usher protein on the outer membrane.

Compared to the FGL chaperones, both the FGS and FGA chaperones do not have an N-terminal extension (Bao et al., 2014). The extended N-terminal residues of FGL chaperones provide additional interactions for subunits with an extended A1 β-strand containing three characteristic sets of consecutive alternating hydrophobic-hydrophilic residues, which is anti-parallel to the subunit’s A strand and becomes part of the subunit’s β-sheet (Zavialov et al., 2003). By contrast, CfaA and related FGA chaperones do not possess an N-terminal extension. They instead feature a hydrophobic A′ β-strand that has two sets of alternating hydrophobic-hydrophilic residues and helps to stabilize the N-terminal residues of the subunit. In particular, residues M3 and Y5 of the chaperone interact with the N-terminal V1 from the A strand of CfaB. The nearby positively charged residue K24 from the B1-C1 loop of CfaA forms a salt bridge with D16 in CfaB (Fig. 3E).

The highly acidic D1′ insertion (residues 41–56) was speculated to interact either with a subunit or with an usher. In the complex structure, residues in this insertion deviate significantly from the apo structure to make contacts with the C-terminus of the subunit, providing specific interactions with the subunit from the main chain atoms of residue G42 and the side chain of residue E46 (Fig. 3D). Thus, the role of the D1′ insertion in contacting the subunit is confirmed. In the complex structure, the characteristic C2-D2′ insertion does not provide any interaction with CfaB, suggesting that this insertion may interact with either the minor subunit CfaE or the usher CfaC or both.

Comparison of dscCfaB and dseCfaB structures and energetic landscape for CFA/I pilus assembly

Unlike the chaperone CfaA, which shows no large structural change beyond the G1 donor strand upon CfaB binding, the donor-strand complemented CfaB from the T112ICfaA/ntdCfaB complex (dscCfaB) displays large structural changes as compared to those of the donor-strand exchanged from the CfaB trimer (dseCfaB), giving rise to a rms deviation of 2.552 Å for 134 equivalent Cα atoms (Figs. S3A and S3B). This deviation should be compared with that for the Caf1 subunit of 1.20 Å (Zavialov et al., 2003), 1.72 for PapA of P-pili (Verger et al., 2007) or 1.52 Å for FimA of Type-1 pili (Crespo et al., 2012). Clearly, the deviation between dscCfaB and dseCfaB is larger than those of pili assembled via the general CUP, which is consistent with the proposal that donor-strand complemented subunits for fimbriae in the alternate CUP or archaic groups are in molten globular state because the subunits in the structures of subunit-chaperone complex in these fimbriae are very much disordered (Pakharukova et al., 2015). It is also worth noting that in the structure of the stabilized CfaA/B complex, the dscCfaB subunit is not disordered (Fig. S3C), suggesting the stabilized dscCfaB is trapped in one of the many conformations.

The large structural change is attributed to an inflated or expanded Ig-like β-sandwich core of dscCfaB (21,457 Å3), which condenses upon donor-strand exchange (20,207 Å3), and to peripheral regions of the β-sandwich, which undergo a structural transition from highly flexible in dscCfaB to well-ordered in dseCfaB. The inflated volume of dscCfaB suggests that it is thermodynamically less stable and presumably is an indication of a high-energy state (Zavialov et al., 2003). Indeed, the dscCfaB is more loosely packed, as the shape complementation index (Sc) between the two β-sheets is only 0.596, as compared to 0.696 for the dseCfaB. These numbers can be compared with those for dscCaf1 and dseCaf1 of 0.58 and 0.71, respectively (Zavialov et al., 2003). Here, a value of Sc = 1 corresponds to two surfaces complemented perfectly to each other, whereas a value of Sc = 0 indicates no complementation between the two surfaces (Lawrence & Colman, 1993). The characteristics of loosely packed β-sheets and an inflated volume displayed by the chaperone-complexed subunits such as dscCaf1 were interpreted as subunits trapped in a high energy state, which is also thought to be the driving force for subsequent pilus assembly (Zavialov et al., 2003).

With the availability of dseCfaB and CfaA/dscCfaB structures, we can now visualize the assembly process for the CFA/I fimbriae at atomic resolution, during which the chaperone G1 strand is replaced by the incoming N-terminal Gd strand from an adjacent subunit. (1) In dscCfaB, as represented by the structure of T112ICfaA/ntdCfaB hetero-dimer, only the P0-P3 pockets of the CfaB hydrophobic groove are fully occupied by residues from the CfaA G1 strand. This can be compared with the dseCfaB, with all pockets (P0-P5) occupied (Fig. 3F). Moreover, residues from the G1 strand of CfaA are bulkier and more hydrophobic than those from the Gd strand of CfaB. These G1 residues act like a wedge, driving into the cleft and forcing the subunit to take a more open conformation. (2) As previously observed (Crespo et al., 2012, Remaut et al., 2006, Van Molle et al., 2009, Verger et al., 2007, Zavialov et al., 2003), the G1 strand pairs with the F strand of CfaB in a parallel fashion, resulting in an atypical Ig fold, whereas the Gd strand runs anti-parallel to the F strand to form a typical Ig fold. (3) The width of the hydrophobic groove, as measured between Cα atoms of flanking A and F strands, is not uniform. Starting at the P2 pocket and going towards the P5 pocket, the groove becomes significantly wider for dscCfaB than for dseCfaB (Fig. 3F). Consequently, the most flexible region of dscCfaB is around the P5 pocket, which has been proposed to serve as the initiation point for the DSE reaction (Remaut et al., 2006).

The above model fits well with the general assembly scheme for pilus biogenesis, although it is difficult to reconcile with the energetics of the off-pathway assembly of trimetic CfaB depicted in Figure 7. While the overall energy requirement for the assembly of CFA/I fimbriae is in line with other fimbria/fibril systems, the energetic landscape may be different, because the driving force for the assembly of the off-pathway trimeric CfaB can’t be derived from the CfaA/dscCfaB complex. This CfaB trimer by definition has three subunits per turn, as compared to 3.17 subunits per turn observed in a previous EM helical reconstruction study of the CFA/I pili (Li et al., 2009a); the lack of observed higher oligomers conceivably is due to kinetic rather than energetic reasons. Since the trimer formation takes place spontaneously and the geometric constraints of the off-pathway CfaB trimer are very similar to those of helical CFA/I pili, it is tempting to speculate that the propensity for CfaB subunits to trimerize may be the driving force for helical assembly of CFA/I pili to proceed with the guidance from the outer membrane usher protein CfaC. This speculation is consistent with the role of chaperone CfaA serving predominantly as a kinetic trap for subunits CfaB, preventing them from off-pathway assembly.

Materials and Methods

Cloning and mutagenesis

Plasmids expressing mature CfaA (residues 20–238, pETDue1-cfaA) and N-terminal hexahistidine-tagged mature CfaB (residues 24–170, pCDFDue-1-(his)6cfaB) were constructed for their expression in the cytoplasm. The vector pCDFDue-1-(his)6cfaB was modified by removing the N-terminal donor strand (residue 24–36) using the Phusion® site-directed mutagenesis kit (New England Biolab, MA) to generate the plasmid pCDFDue-1-(his)6ntdcfaB (residue 37–170). The expressing vector pETDue1-cfaA was also modified by inserting a Strep-tag (WSHPQFEK) directly following the CfaA coding region to generate pETDue1-cfaA(Strep). The plasmid pMAM2 encoding the entire CFA/I operon (CfaABCE) has been described previously (Li et al., 2007).

Mutations were introduced to both pETDue1-cfaA(Strep) and pMAM2 vectors, using Phusion site-directed mutagenesis kit (New England Biolab, MA), to generate two sets of eight CfaA mutants: pETDue1-cfaA(T112I)(Strep) and pMAM2(cfaA:T112I), pETDue1-cfaA(T112I/L114I/V116I)(Strep) and pMAM2(cfaA:T112I/L114I/V116I), pETDue1-cfaA(L114A/V116A)(Strep) and pMAM2(cfaA:L114A/V116A), pETDue1-cfaA(N180A)(Strep) and pMAM2(cfaA:N180A), pETDue1-cfaA(Y182A)(Strep) and pMAM2(cfaA:Y182A), pETDue1-cfaA(R154A)(Strep) and pMAM2(cfaA:R154A), pETDue1-cfaA(N180A/Y182A)(Strep) and pMAM2(cfaA:N180A/Y182A), and pETDue1-cfaA(N180A/Y182A/R154A)(Strep) and pMAM2(cfaA:N180A/Y182A/R154A). The primers used are summarized in Table S1

Protein expression and purification

To express Strep-tagged CfaA (CfaA(Strep)) or hexahistidine-tagged CfaB ((his)6CfaB) by itself, the pETDue1-cfaA(Strep) variants or pCDFDue-1-(his)6cfaB were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, NY) cells separately. Transformed E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in 1 L Terrific Broth (Research Products International Corp., IL) containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin. When OD600 reached 0.8 for the cell culture, protein expression was induced by adding isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) to a final concentration of 0.8 mM. After a further 16 hours of incubation at 18°C, cells were collected by centrifugation. Cell pellets were resuspended in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 and 150 mM NaCl and homogenized twice at 900 bar with the aid of an APV-2000 homogenizer (APV USA, WI). After a high-speed centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was loaded onto a column containing either Ni-NTA superflow resin (Qiagen, Germany) for (his)6CfaB or Strep-Tactin superflow plus resin (Qiagen, Germany) for CfaA(Strep) pre-equilibrated with a binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5 and 100 mM NaCl). Columns were washed with the binding buffer supplemented with 30 mM imidazole three times, and the protein sample on the Ni-NTA matrix was eluted with the binding buffer supplemented with 300 mM imidazole. The protein sample on the Strep-Tactin column was eluted with the binding buffer supplemented with 2.5 mM D-desthiobiotin. Affinity purified samples were subjected to size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 75, 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare Life Science, NJ). Final eluate was concentrated using an Amicon 35 concentrating device (Millipore, MA) and stored at -80°C before use.

To produce the CfaA/B complex, either pCDFDue-1-(his)6cfaB or pCDFDue-1-(his)6ntdcfaB was co-transformed with pETDue1-cfaA(Strep) variants into BL21(DE3). The resulting E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in 1 L Terrific Broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml each of streptomycin sulfate and ampicillin. At a cell density of 0.8 at OD600, expression was induced by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 0.8 mM. The culture was cooled to 18°C and further incubated for 16 hours before the cells were collected by centrifugation. The CfaA/B complex was purified in a two-step tandem affinity chromatographic procedure using a Strep-Tactin column after a Ni-NTA column. Concentrated protein samples (5–8 mg/ml) were stored at -80°C before use. BN-PAGE was used to check oligomerization of CfaB subunits and CfaA/B complex formation as described (Ma & Xia, 2008).

Crystallization and structure determination

Protein crystallization was carried out by the vapor-diffusion method at 293 K, mixing 1 μl of protein with 1 μl of well solution. CfaB (8 mg/ml) was crystallized using a well solution of 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.0, 0.2 M MgCl2, 3% ethanol glycol, 16.8% PEG8000. Crystals of CfaA/B complex (5.3 mg/ml) were obtained with the well solution containing 0.1 M NaOH-citrate pH 5.0, 20% PEG8000. For the mutant CfaAT112I-NtdCfaB complex, the protein (8.5 mg/ml) was mixed with Na2HPO4-NaH2PO4 pH 6.6, 9% PEG8000. All crystals were flash-cooled in propane in the presence of 20%-30% glycerol.

Diffraction data sets were recorded at the SER-CAT ID beamline at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) with a MAR300 CCD detector. Diffraction images were indexed and diffraction spots were integrated and scaled using the HKL2000 software package (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997). Structures were solved by the molecular replacement method using CfaB (PDB code 3F85) (Li et al., 2009a) and CfaA (PDB code 4NCD) (Bao et al., 2014) as phasing templates with the program suite PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010). Subsequent cycles of manual model rebuilding with Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004) and refinement with PHENIX improved the qualities of structural models (Table 1), which were validated using Molprobity (Chen et al., 2010) before being deposited in the Protein Data Bank.

Detection of CfaA/B complex formation

CfaA(Strep) bound to (his)6CfaB was retained to the Ni-NTA beads because of the hexahistidine tag of CfaB and eluted after washing three times. Fractions of this eluate were loaded onto 12% Bis-Tris polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen, NY), which were stained by Coomassie blue after electrophoresis. The unbound CfaA(Strep) in Ni-NTA flow-through was detected by Western blot using a anti-CfaA serum (1:5000 dilution). The amount of CfaA recovered from the Ni-NTA column for each variant was compared with wild-type control to determine the relative amount of CfaA binding to (his)6CfaB.

Measurements of CfaA-assisted CfaB refolding rate

Purified CfaB (87.5 μM) was incubated with a solution containing 5 M GdnHCl in PBS buffer for 2 hours at 25°C. A LS 55 Fluorescence Spectrometer, 120V (PerkinElmer Inc., MA) was used to acquire the equilibrium tryptophan fluorescence spectrum of CfaB at an excitation wavelength of 290 nm (3-nm bandwidth for both excitation and emission). All refolding experiments were performed at 25°C in PBS buffer. Equilibrium fluorescence emission spectral scans were recorded in the wavelength range from 300 to 400 nm for solutions containing 3.3 μM CfaB and 7.2 μM CfaA with or without 5 M GdnHCl with buffer background subtracted.

Measurements of CfaB refolding rates were initiated by rapid mixing of fully unfolded CfaB into a PBS buffer (35-fold dilution) with or without 7.2 μM CfaA variants. Recording for changes in tryptophan fluorescence at 313 nm began prior to mixing and continued for every 20 milliseconds after mixing (dead time = 1 s). Fluorescence intensity traces representing the refolding of CfaB were fitted with a single-exponential growth function

| (Eq. 1) |

or a double-exponential growth function

| (Eq. 2) |

where k is the rate constant, I∞ is total fluorescence intensity and %sI∞ and %fI∞ is the percentage of total intensity for the slow and fast phases, respectively. The kinetic model for CfaB refolding was analyzed according to

| (Eq. 3) |

and

| (Eq. 4) |

where CfaBU is unfolded CfaB, CfaA/BN is the chaperone-subunit complex and CfaBN is the folded CfaB. The calculated folding parameters from three trials were averaged for each measurement (Table 2). The baseline measurement with 7.2 μM CfaA alone was recorded and subtracted from all CfaA-assisted CfaB refolding results, and the data sets were fitted using the GraphPad software Prism 7.

CFA/I pili fimbriation assay

The E. coli BL21-AI (Invitrogen, NY) strain transformed with pMAM2 or its variants was grown in LB media containing 0.1% glucose and 50 μg/ml of kanamycin at 37 °C. Arabinose was added to the culture to a final concentration of 0.2% to induce CFA/I fimbriation when cell density was grown to an OD600 of 2.0. Cells were collected 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, or 90 minutes post induction.

The level of cell surface assembled pili was quantified by a modified competitive bact-ELISA method (Prieto et al., 2003). Briefly, 1.5 ml of bacteria was washed three times with PBS. To coat a 96-well Maxisorp plate (Nunc, Denmark), 100 μl of a final bacterial suspension in PBS (OD600 of 0.6) was placed in each well and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with shaking at 200 rpm. The wells were washed with PBS buffer three times and dried on paper towels. After 1 hour blocking with PBS buffer plus 1% BSA at room temperature and subsequent repeated washing, the primary rabbit polyclonal antiserum (1:10000 dilution) against CfaB were added and incubated for 1 hour followed by three more washes. After incubation for 1 hour with a secondary antibody (AP conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, Pierce), the wells were washed with PBS buffer plus 0.05% Tween 20 three times. 150 μl per well of AP substrate solution (Pierce) was added and incubated for 30 min. The reaction was stopped by adding 150 μl 1 M NaOH. Absorbance at 405 nm was recorded for each well.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the beam line staff of the SER-CAT at APS, ANL for assistance in data collection and George Leiman for editorial assistance. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and by a grant from the Trans NIH/FDA Intramural Biodefense Program (to D.X.) and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Programs 81501787 to R.B). The research was also supported by the U.S. Army Military Infectious Diseases Research Program Work Unit Number A0307 (to S.J.S.), and by the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine (S.J.S.).

Abbreviations

- BN-PAGE

Blue-Native PAGE

- CFA/I

colonization factor antigen I

- CUP

chaperone-usher pathway

- ETEC

enterotoxigenic E. coli

- dsc (DSC)

donor-strand complementation

- dse (DSE)

donor-strand exchange

- FGA

F1-G1 alternate

- FGL

F1-G1 long loop

- FGS

F1-G1 short loop

- Gd strand

donor strand from subunit to complete the Ig fold

- G1 strand

donor strand from the chaperone

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- GndHCl

Guanidinium chloride

- SEC

size-exclusion chromatography

- rms deviation

root-mean-square deviation

Footnotes

Coordinates Atomic coordinates of the refined structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (www.pdb.org) with the pdb code 4Y2O for the structure of CfaAB complex and 4Y2N for CfaB trimer expressed in the cytosol, and 4Y2L for the CfaB trimer grown from dissociated wild-type wtCfaA/B complex.

Author contributions: RB designed and performed work and wrote the paper; YL analyzed the data; SJS provide the material and discussion; DX obtained the funding, designed and performed work, and wrote the paper.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anantha RP, McVeigh AL, Lee LH, Agnew MK, Cassels FJ, Scott DA, Whittam TS, Savarino SJ. Evolutionary and Functional Relationships of Colonization Factor Antigen I and Other Class 5 Adhesive Fimbriae of Entorotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72:7190–7201. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.12.7190-7201.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bann JG, Pinkner JS, Frieden C, Hultgren SJ. Catalysis of protein folding by chaperones in pathogenic bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17389–17393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408072101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao R, Fordyce A, Chen YX, McVeigh A, Savarino SJ, Xia D. Structure of CfaA suggests a new family of chaperones essential for assembly of class 5 fimbriae. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1004316. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnhart MM, Pinkner JS, Soto GE, Sauer FG, Langermann S, Waksman G, Frieden C, Hultgren SJ. PapD-like chaperones provide the missing informaiton for folding of pilin proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000;97:7709–7714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130183897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens S. Periplasmic chaperones--preservers of subunit folding energy for organelle assembly. Cell. 2003;113:556–557. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin I, Wiklund G, Qadri F, Torres O, Bourgeois AL, Savarino S, Svennerholm AM. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli with STh and STp genotypes is associated with diarrhea both in children in areas of endemicity and in travelers. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3872–3877. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00790-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury D, Thompson A, Stojanoff V, Langermann S, Pinkner J, Hultgren SJ, Knight SD. X-ray Structure of the FimC-FimH Chaperone-Adhesin Complex from Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science (New York, NY. 1999;285:1061–1066. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo MD, Puorger C, Scharer MA, Eidam O, Grutter MG, Capitani G, Glockshuber R. Quality control of disulfide bond formation in pilus subunits by the chaperone FimC. Nature chemical biology. 2012;8:707–713. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria P, Verhaert L, Basaca-Sevilla V, Banson T, Cross J, Orskov F, Orskov I. Search for heat-labile enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in humans, livestock, food, and water in a community in the Philippines. J Infect Dis. 1978;138:87–90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/138.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DG, Evans DJ, Jr, Clegg S, Pauley JA. Purification and characterization of the CFA/I antigen of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1979;25:738–748. doi: 10.1128/iai.25.2.738-748.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science (New York, NY. 2002;295:1852–1858. doi: 10.1126/science.1068408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung DL, Knight SD, Woods RM, Pinkner JS, Hultgren SJ. Molecular basis of two subfamilies of immunoglobulin-like chaperones. Embo J. 1996;15:3792–3805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn MJ, Ogg DJ, Kihlberg J, Slonim LN, Flemmer K, Bergfors T, Hultgren SJ. Structural basis of pilus subunit recognition by the PapD chaperone. Science (New York, NY. 1993;262:1234–1241. doi: 10.1126/science.7901913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MC, Colman PM. Shape complementarity at protein/protein interfaces. Journal of molecular biology. 1993;234:946–950. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YF, Poole ST, Nishio K, Bullitt E, Rosulova F, Savarino SJ, Xia D. Structures of CFA/I Fimbriae from Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009a;106:10793–10798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812843106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YF, Poole ST, Rasulova F, McVeigh A, Savarino SJ, Xia D. A receptor-binding site as revealed by the crystal structure of CfaE, the CFA/I fimbrial adhesin of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23970–23980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700921200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YF, Poole ST, Rasulova F, McVeigh A, Savarino SJ, Xia D. Crystallizations and Preliminary X-ray Diffraction Analyses of Several Forms of the CfaB Major Subunit of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli CFA/I Fimbriae. Acta Cryst. 2009b;F65:242–247. doi: 10.1107/S1744309109001584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Xia D. The use of blue native PAGE in the evaluation of membrane protein aggregation states for crystallization. J Appl Crystallogr. 2008;41:1150–1160. doi: 10.1107/S0021889808033797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuccio SP, Baumler AJ. Evolution of the chaperone/usher assembly pathway: fimbrial classification goes Greek. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2007;71:551–575. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00014-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Method Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pakharukova N, Garnett JA, Tuittila M, Paavilainen S, Diallo M, Xu Y, Matthews SJ, Zavialov AV. Structural Insight into Archaic and Alternative Chaperone-Usher Pathways Reveals a Novel Mechanism of Pilus Biogenesis. PLoS pathogens. 2015;11:e1005269. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prieto CI, Rodriguez ME, Bosch A, Chirdo FG, Yantorno OM. Whole-bacterial cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for cell-bound Moraxella bovis pili. Veterinary microbiology. 2003;91:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puorger C, Vetsch M, Wider G, Glockshuber R. Structure, folding and stability of FimA, the main structural subunit of type 1 pili from uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. J Mol Biol. 2011;412:520–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remaut H, Rose RJ, Hannan TJ, Hultgren SJ, Radford SE, Ashcroft AE, Waksman G. Donor-strand exchange in chaperone-assisted pilus assembly proceeds through a concerted beta strand displacement mechanism. Mol Cell. 2006;22:831–842. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer FG, Futerer K, Pinkner JS, Dodson KW, Hultgren SJ, Waksman G. Structural Basis of Chaperone Function and Pilus Biogenesis. Science (New York, NY. 1999;285:1058–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer FG, Remaut H, Hultgren SJ, Waksman G. Fiber assembly by the chaperone-usher pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1694:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarino SJ, Brown FM, Hall E, Bassily S, Youssef F, Wierzba T, Peruski L, El-Masry NA, Safwat M, Rao M, Jertborn M, Svennerholm AM, Lee YJ, Clemens JD. Safety and immunogenicity of an oral, killed enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-cholera toxin B subunit vaccine in Egyptian adults. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:796–799. doi: 10.1086/517812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto GE, Dodson KW, Ogg D, Liu C, Heuser J, Knight S, Kihlberg J, Jones CH, Hultgren SJ. Periplasmic chaperone recognition motif of subunits mediates quaternary interactions in the pilus. EMBO J. 1998;17:6155–6167. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanassi DG, Saulino ET, Hultgren SJ. The chaperone/usher pathway: a major terminal branch of the general secretory pathway. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:223–231. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanassi DG, Stathopoulos C, Karkal A, Li H. Protein secretion in the absence of ATP: the autotransporter, two-partner secretion and chaperone/usher pathways of gram-negative bacteria (review) Molecular membrane biology. 2005;22:63–72. doi: 10.1080/09687860500063290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Molle I, Moonens K, Garcia-Pino A, Buts L, De Kerpel M, Wyns L, Bouckaert J, De Greve H. Structural and thermodynamic characterization of pre- and postpolymerization states in the F4 fimbrial subunit FaeG. J Mol Biol. 2009;394:957–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verger D, Bullitt E, Hultgren SJ, Waksman G. Crystal structure of the P pilus rod subunit PapA. PLoS pathogens. 2007;3:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vetsch M, Puorger C, Spirig T, Grauschopf U, Weber-Ban EU, Glockshuber R. Pilus chaperones represent a new type of protein-folding catalyst. Nature. 2004;431:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nature02891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waksman G, Hultgren SJ. Structural biology of the chaperone-usher pathway of pilus biogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:765–774. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavialov AV, Berglund J, Pudney AF, Fooks LJ, Ibrahim TM, MacIntyre S, Knight SD. Structure and Biogenesis of the Capsular F1 Antigen from Yersinia pestis: Preserved Folding Energy Drives Fiber Formation. Cell. 2003;113:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00351-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavialov AV, Kersley J, Korpela T, Zav’yalov VP, MacIntyre S, Knight SD. Donor strand complementation mechanism in the biogenesis of non-pilus systems. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:983–995. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavialov AV, V, Tischenko M, Fooks LJ, Brandsdal BO, Aqvist J, Zav’yalov VP, Macintyre S, Knight SD. Resolving the energy paradox of chaperone/usher-mediated fibre assembly. Biochem J. 2005;389:685–694. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.