INTRODUCTION

Consumption of a plant-based diet is associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD). The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends 3 servings of whole grains, 4–5 servings of vegetables and 4–5 servings of fruit daily along with 4–5 weekly servings of nuts, seeds, and legumes, and 2 servings of omega-3 rich fish weekly (1). However, dietary habits are dependent upon both individual and environmental factors, particularly in rural areas where socioeconomic factors contribute to poor eating habits. The diet commonly consumed by Appalachians consists of a high amount of calorie-dense meats and starches that are often fried. Although there are some healthy components of the traditional Appalachian diet (i.e., high intake of legumes and vegetables), the typical fats used in food preparation (2), increased access to fast food and rising food costs are all barriers to healthy eating in this region (3,4). Following implementation of a culturally-appropriate nutrition education and cooking skills program in Central Appalachia, a focus group was conducted to evaluate the motivation to attend monthly cooking classes. The purpose of this qualitative study was to determine the attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control beliefs that influenced participation in these cooking classes.

BACKGROUND

Behavior change barriers exist at the individual, family and environmental levels, and recognition of these barriers dictates the levels the intervention should target (5,6). Identification of all barriers provides insight into the appropriate theoretical framework to use for development of successful interventions (7). Underestimation of barriers results in less success in sustaining healthy lifestyle activities (8). Some barriers are related to socioeconomic status and may be non-modifiable, which necessitates creative solutions to individualized advice and training (9). A cooking skills program was developed and implemented in rural Appalachia. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) was used to evaluate the motivation of participants to enroll and continue the cooking classes for a 12 month period. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) constructs, including attitudes (i.e., personal value of behavior change), subjective norms s(i.e., perceived behavioral expectations of others), perceived behavioral control (PBC; perceived ability to change behavior within the context of perceived barriers) and intention (i.e., readiness to perform a behavior), provide a framework for assessment of individual strengths and barriers to behavioral change (10).

A thorough assessment of factors that impede or promote dietary behavior change is important prior to development of interventions (1–12). Factors that affect diet in Breathitt County, Kentucky, a rural Appalachian food desert where we implemented the cooking skills classes, were assessed prior to development and implementation of this intervention. Nominal group sessions were conducted during which participants provided themes related to healthy eating barriers identified through personal experience. This technique generates more ideas than traditional discussion groups and allows groups to appropriately prioritize factors that affect diet (13). A plant-based meal was catered for the participants. Following the meal, participants were asked “What would have to change or remain the same for you to consistently eat healthy meals like this one?” During these sessions, participants reported several barriers to healthy eating. These included costs, limited knowledge about the health benefits of specific foods, length of time required to prepare foods, feelings of being deprived of favorite foods, response of family members to new foods and cooking techniques, convenience of fast food, life-long habits and the community environment (e.g., distance to grocery stores, availability of a variety of fresh produce)(14). Younger participants [F (2, 40) = 3.53, p=.04] and those with lower (<$25,000) incomes [F (7, 35) = 2.75, p=.02] were more likely to identify food cost as a barrier to adherence, compared to those who were older with higher incomes. While cost can be a barrier to healthy eating, 26% of individuals in Breathitt County with low consumption of healthy foods have middle to high incomes, indicating other factors affect food accessibility. Participants with lower educational levels were more likely to report family members would be hesitant to try a healthy meal [F (4, 38) = 4.08, p = .008]. Education and income levels tend to be directly related and many of these individuals expressed concern that trying new foods would create the risk of having to “throw out what I made and cook something else they will eat,” resulting in a waste of their funds budgeted for food. Women were more likely than men to view food as a means of health promotion [t (41) = −7.18, p = ≤.000]. Based on these findings, a culturally-specific intervention aimed at improving dietary patterns was developed and piloted in this region.

Cooking skills programs that have multifaceted targets tend to be much more successful in altering dietary patterns than those programs that target only one contributing factor (15–18). Therefore, the cooking classes included multiple strategies known to improve eating habits (i.e., reduced food preparation time, information about health benefits of foods, menu planning, nutrition label comprehension and family involvement). The classes were based on two behavior change techniques (i.e., provision of dietary instructions and prompting practice) known to result in sustained dietary behavior (19,20). These techniques involve both providing instructions about how to change dietary behaviors as well as giving individuals the opportunity to practice those behaviors (21). County USDA Cooperative Extension Family and Consumer Science (FCS) agents served as primary instructors. Agents demonstrated time-saving cooking techniques and recipe preparation using recipes from six cookbooks provided to each participant. Participants also received six food preparation tools to reduce the time spent preparing foods for consumption. Food ingredients were provided for each participant to prepare a full recipe and take it home to share with family members. All of the recipes met AHA dietary recommendations. Prior to implementation of the classes, field observations of the two county groceries were conducted. To ensure that participants could replicate the recipes, only food ingredients that were readily available at the county grocery stores were used in the classes.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

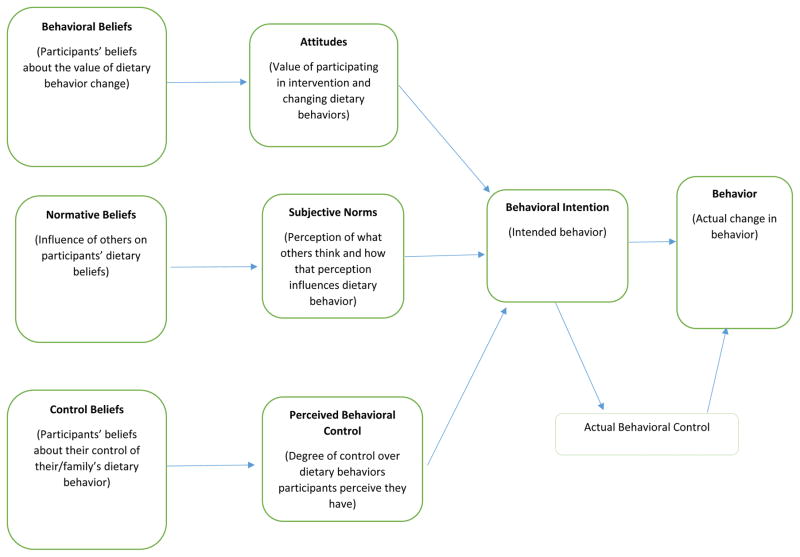

Social cognitive theories, including TPB, aid in explaining health behaviors which are influenced by social and psychological determinants. These theories help guide interventions aimed at changing lifestyle behaviors. Interventions based on these theories tend to be more effective than atheoretical interventions (1-). The TPB can be used for development, implementation and evaluation of intervention strategies (10). In this evaluation, a TPB-based guided interview was used to explore factors that influenced participation. The TPB posits that behavior is guided by three considerations, perceived consequences of changing behavior (attitude), perceived expectations of others (subjective norm) and perceived facilitators or barriers to the ability to change (perceived behavioral control). Attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control form a behavioral intention, which is the immediate antecedent of a behavior (10, 21). Changes in intention and actual behavior are dependent upon changes in attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (10, 21). Because realistic perceived interventions must be predicated upon a thorough assessment of perceived behavioral control as well as attitudes and subjective norm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theory of planned behavior in context of dietary behavior change [15]

Attitudes

Beliefs about the outcomes of behaviors and the value of these outcomes affect the intention to perform behaviors (21). In a preliminary study in this rural Appalachian region, food cost, the length of time required to prepare healthy foods, feelings of being deprived of more appealing foods, the difficulty of changing life-long habits and limited knowledge about the health benefits of certain foods were assessed as barriers to healthy eating (14). The classes were developed to address each of these barriers.

Participants learned how to read nutrition labels and were given cost comparisons of generic vs. brand name ingredients. Recipes were modifications of dishes or meals frequently consumed in this region (e.g., baked instead of fried fish nuggets, chicken and vegetable casserole instead of fried chicken). All of the recipes consisted of very few ingredients and “time-saving tips” were included in the demonstration (e.g., dicing an onion with the peel intact). The health benefits of foods were reinforced by using cookbooks developed for CVD risk reduction and agents discussed health benefits during class sessions.

Subjective Norms

The individual’s subjective norm (i.e., beliefs about what other people think the individual should do and the individual’s motivation to comply with the opinions of others) also influences their behavioral intention (22). In a preliminary study, respondents felt that family response to new foods and cooking techniques significantly influenced their decision to try healthier cooking because if their families did not eat the food, they incurred additional expense by having to prepare another meal. To accommodate the concern of “losing money if I cook healthy foods,” participants prepared and took home a full recipe at no cost.

Perceived Behavioral Control

Performance of a behavior is influenced by the presence of adequate resources and ability to control barriers to behaviors. The more resources and fewer obstacles individuals perceive, the greater their perceived behavioral control and the stronger their intention to perform behaviors (22). Individuals may have the intention to change and sustain certain health behaviors, but their daily environment may not be conducive to those behaviors (22). The convenience of fast food and the community environment (i.e., lack of accessibility and affordability of healthy foods in local grocery stores) were reported as the barriers to healthy eating on a consistent daily basis.

During the cooking skills classes, volitional control was enhanced by a) providing free cookbooks; b) providing free food preparation tools with demonstrations and opportunities to practice tool use; c) using common ingredients available at relatively low cost in the study county, d) allowing participants the option of not attending every monthly class but still being able to pick up their cookbooks and tools at no charge, and e) choosing some recipes that mimicked fast foods (e.g., fish nuggets) but were prepared using techniques that enhanced the CVD risk reducing properties of the food.

Behavioral Intention

Attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavior control are determinants of behavioral intention (22). A strong association between behavioral intention and actual performance of a behavior is dependent on volitional control (i.e., the degree to which the individual has complete control to decide at will whether or not to perform a behavior) (22). Intervention strategies that specifically reinforce facilitators of or minimize barriers to healthy behaviors are more likely to result in sustained behavior change than those that do not address attitude, subjective norm and perceived behavioral control. By addressing all three aspects of behavioral intention, this intervention not only had a greater likelihood to establish sustained behavior change but the theory constructs provided a framework upon which to evaluate the effect of the intervention.

METHODS

This project was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board (12-0362-P2H). A focus group using a guided interview was conducted with 10 participants at midpoint of the 12-month cooking skills intervention. Interview questions were based on the TPB constructs (Table 1). Participants’ motivation to enroll in and continue a 12-month longitudinal study aimed at increasing home-preparation and consumption of CVD-risk reducing foods was evaluated. Participants were at least 18 years of age. Participants were recruited via a voucher in local newspapers and free shopper flyers. Volunteers (n=306) returned a completed voucher to one of the two county grocery stores where they received a $5 gift card as part of a cross-sectional survey of purchasing patterns. During this survey, all participants were offered the opportunity to enroll in cooking classes taught at the county USDA Cooperative Extension. These classes involved a 12-month commitment to attend monthly classes at the Extension office located centrally in the county. A subsample of 38 individuals volunteered to participate in the 12-month cooking skills classes (23). Physical class space and extension personnel availability limited the number of people who could participate in this feasibility study.

Table 1.

Guided interview questions based on the Theory of Planned Behavior constructs

| TPB Construct | Questions |

|---|---|

| Attitudes | Tell me what motivated you to sign up for the classes. |

| Tell me about why you keep coming back to each class. | |

| What are your thoughts on the meals you prepared in class? | |

| What are your thoughts about the cookbooks and cooking tools you received in class? | |

| Subjective Norms | Have you talked to your family or friends about the classes or anything you learned in class? |

| Where do you get your inspiration for meals? | |

| Perceived Behavioral Control | Have you noticed any changes in the way you think about food since you started the classes? |

| Have there been any changes in the amount of fresh fruits and vegetables you eat? | |

| Behavioral Intention | Tell me about preparing the recipes at home. |

| Are there other ways the class has impacted you? |

Using demographics to obtain a representative sample of all participants who enrolled in the cooking classes, 10 class participants were invited to and attended the focus group. The group session was led by a qualitative public health researcher not involved in the longitudinal study. Focus group participants ranged in age from 35–87 years and 8 of the 10 participants were females. The session was conducted at a location separate from the cooking class location and with no other study personnel present. Interview questions were grouped into predefined sets, with each relating to an element of the TPB, including attitudes toward class participation and retention, subjective norms that facilitated or discouraged participation, perceived behavior control over healthful cooking and behavioral intention.

The research team developed the interview protocol and sequencing of questions after reviewing the literature about developing interview guides that elicit the constructs of the TPB (20–22). The interview questions were reviewed by two community members not enrolled or involved in the study in order to ensure cultural sensitivity. Probing and promoting suggestions were included in the interview guide to enable expansion and clarification of responses (22). Class participants were asked to respond to questions about their experiences participating in the cooking classes. The group session was audiotaped and the researcher took brief notes to use as a prompts for additional questions. Following the interview, the audio transcript was imported into NVivo 10 and coded by interview question. Major themes were identified by frequency, intensity, and extensiveness of comments (21, 24). Results were then summarized and compiled in response to project research questions. Negative comments were also explored.

RESULTS

Attitudes

Focus group participants shared overwhelmingly positive individual attitudes about the cooking classes (Table 2). Attitudes that prompted participation included having new experiences and making new friends. The classes provided new resources to those who were looking for easy methods of preparing healthy meals. The anticipated health benefits of healthy cooking enhanced participation. Participants in the focus group expected that overall eating habits would eventually improve as a result of being in the classes. “Slimming down over time” after incorporating techniques from class into their daily lives was also a participant expectation. Family members’ health also motivated focus group participants to learn how to prepare healthy meals.

Table 2.

Participant statements reflecting attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control constructs about cooking skills intervention

| ATTITUDES

| |

|---|---|

| Themes | Examples of Participant Statements |

| New experiences | “There’s not a lot offered around here, so the cooking class is wonderful.” |

| “It was something fun and enjoyable.” | |

| Social interaction | “I wanted to do something with my mother” |

| “I brought my little girl with me to the classes so she could help me” | |

| “We made it our date night.” | |

| Provided new resources | “I am always looking for new recipes and strategies for meal preparation.” |

| “I grew up as a ‘fast food child’ and never learned how to cook healthy.” | |

| “I like to try new things and I love to collect recipes” | |

| “It was an opportunity to try new recipes. | |

| “I wanted to learn new recipes that my family would like.” | |

| Health improvements | “…to help control my blood pressure and cholesterol.” |

| “…to slim down over time.” | |

| SOCIAL NORMS

| |

|---|---|

| Themes | Examples of Participant Statements |

| Family attachment | Positive |

| “my daughter was such a help in making [the past] and she really enjoyed it. I don’t know if it’s because she really liked it or if it was because she helped make it.” | |

| “I’m giving more fruit to my 4-year-old grandson.” | |

| “My children liked the food I brought home.” | |

| “My husband would get excited and ask about what I was going to bring home from class that night.” | |

|

| |

| Negative | |

|

| |

| “When I fix something new, my husband will say ‘don’t fix it again.’ | |

| “My family did not like them…my husband and my son will eat just about anything…” | |

| “…they would eat it, but they wouldn’t go back for seconds and I’d end up having to throw the rest away…if I was to purchase… and make this food, I would be wasting money.” | |

| “If it’s healthy, children won’t look at it. And if you can’t get it at McDonald’s and Wendy’s, they don’t want it.” | |

|

| |

| Traditional and cultural values | “You have to want to be healthy, but we’re so used to cooking traditional food – what our mothers and grandmothers fixed.” |

| “I do a lot of ‘country cooking’ and this was not country cooking.” | |

| “The fish bites were more of what we are used to… enjoyed learning to make homemade low-fat tartar sauce.” | |

| PERCEIVED BEHAVIORAL CONTROL

| |

|---|---|

| Theme | Examples of participant statements |

| Cost-free opportunity to try new foods | “Money dictates what’s available in stores locally and dictates what most people locally will buy.” |

| “If part of the purpose of the class is to get people to try new things, and new ways of cooking, it accomplished that task.” | |

| “If healthy food was cheaper than bad food, it would be healthier for your pocket book.” | |

| “…looking for cheap food that will fill up my family, something like a casserole.” | |

|

| |

| Gradual introduction of healthy recipes into meals | “I’m starting to eat a little bit more broccoli. I used to pick it out of every dish.” |

| “Never knew that you could bake a cabbage before this class” | |

|

| |

| Food preparation skills | “We eat more vegetables now because they’re quicker and easier to fix” |

| “I love my vegetable peeler” | |

Subjective Norms

Family attachments primarily dictated subjective norms (Table 2) and included bonding with other family members during classes, preparing recipes that families would enjoy, and family members looking forward to foods brought home from classes. Multiple mother-daughter dyads had joined the cooking classes together as a bonding activity. One focus group attendee described establishing a night out with her young daughter. She was hopeful that participation in the class expanded her daughter’s enthusiasm for healthy cooking and eating. A married couple interviewed during the focus group discussed using the classes as a date night activity. They noted that joint engagement in the classes helped ease their household transition toward healthier day-to-day eating.

Focus group participants who did not have family members in the cooking skills classes reported both positive and negative subjective norm factors. When asked to discuss how family members at home responded to being served dishes from class, some participants reported that family members looked forward to trying the new recipes. For example, one woman mentioned that over time, on class days her husband began asking in anticipation and excitement about what dish would be prepared. Conversely, other focus group participants experienced pushback from family members. Many of the adverse comments were colored by traditional norms that were contrary to both healthful cooking and change. One woman noted simply, “It’s hard to teach an old dog new tricks.”

Perceived behavioral control

Perceived behavioral control included opportunities to try new foods without concern about food waste, the ability to incrementally introduce healthy foods into family meals and learning how to use food preparation tools (Table 2). Food waste and cost of food was a major theme that negatively affected individual perceived control over healthy cooking at home. The cost of food may have been the most important factor affecting food decisions of these individuals, more so than taste or nutritional value of the food. For participants whose family members were hesitant to try new dishes, there was concern about food waste. Food cost and fear of wasting food may make exploration of new, healthier dishes prohibitive for many low income families. Having the opportunity to experiment with new foods and techniques in class allowed participants to temporarily alleviate these concerns.

Finally, provision of food preparation tools also increased participants’ perception of their ability to implement healthy changes. For example, the married couple noted that they began to “eat more vegetables because they’re quicker and easier to fix,” while others offered examples such as incorporating better food measurements in home food preparation and finding benefit in cooking from the diabetic cookbook provided. Certainly the novelty of having access to new tools that many may not have bought for themselves likely influenced their use.

Behavioral Intention

Despite difficulties with introducing entire dishes, almost all participants noted that they had been able to slowly incorporate healthy foods into family meals over time. “I’m starting to eat a little bit more broccoli. I used to pick it out of every dish,” noted one participant. Another woman discussed being inspired to introduce more fruit to her 4-year-old grandson’s diet. Following introduction to new readily-available ingredients not found in traditional local dishes (e.g., acorn squash, cilantro), several participants bought those ingredients during subsequent grocery store trips. Some individuals reported reducing sodium intake while creatively incorporating alternative seasonings. Cost-free opportunities to try simple recipes for affordable foods were key to behavior intentions translating into actual behavior change.

CONCLUSION

Participant attitudes, subject norms and perceived behavioral control are antecedents to behavior change because these constructs are directly associated with behavior intention. Identifying these motivators using the TPB can provide the framework for greater efficacy of interventions. Participants viewed the monthly cooking classes as opportunities for social interaction and new experiences, to access new resources and to improve their health. Subjective norms were mostly influenced by family members and traditional methods of cooking. Perceived behavioral control was influenced by the opportunity to try new foods without concern about food waste, acquisition of the knowledge to incrementally introduce healthy foods into family meals and enhanced skills via the use of food preparation tools.

The cost of food and feeding a family within a limited budget were concerns for participants. These concerns are common in regions with high rates of poverty. Providing the means and methods of incorporating less expensive, locally available healthy foods into family meals and reducing preparation time can be achieved through evidence-based interventions taught at Cooperative Extension offices. Rural Appalachian food deserts have high rates of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and, for individuals receiving SNAP funding, time spent preparing food is a key determinant in whether or not healthful foods are frequently prepared and consumed. Strategies that increase awareness of affordable foods available in local grocery stores and improve participant knowledge of the health attributes of these foods have the potential to improve dietary habits. Providing the skills and resources to decrease the amount of time and effort required to prepare healthier meals also increases the likelihood of healthy eating.

Previous interventions have not always addressed the socioeconomic factors that affect dietary behaviors in Appalachia. The food history of Appalachia reflects adaptation to sparse resources and the limited variety of food options over generations. This reality of limited resources was reflected in comments from participants. There was discussion that in any community-based health or lifestyle intervention, they have to rush to make sure that they get whatever is being offered: “If you get there on time, it’s gone.” It is likely that this concern is a global reality in most socioeconomically depressed regions where access to resources is limited.

In rural Appalachian food deserts and other regions with limited socioeconomic means, nutritional interventions must be developed in the context of very limited resources and should include dietary adaptation instructions. Traditional recipes and cooking methods may be altered slightly so that participants can slowly introduce healthier foods into family meals. In particular, many nations have an agrarian history that can be the basis of healthy eating interventions. In this study, participants provided suggestions for future nutritional interventions. Demonstrations by local FNS specialists, being able to prepare a recipe during the classes and taking a full recipe home for their family to eat were all viewed as unique and positive aspects of the cooking classes. The FNS specialists also provided price comparisons of brand and generic food items, as well as alternative options for those with special dietary preferences or needs.

The principal investigator, who is a native of Central Appalachia, and research personnel who have worked extensively in Appalachia, were present at each of the cooking classes and developed a relationship with participants. Contact with the primary researcher and other study personnel resulted in an unexpected positive component of the intervention. Participants expressed gratitude that efforts were being made to improve dietary habits in their community.

It makes you feel real special.

[They] went above and beyond for us.

We’ve never had anyone else to give us those things before.

We’re being treated like royalty.

It always felt nice that they gave us the extra food ingredients to take home.

Family, kinship, and a strong sense of community are deeply held values of Appalachians (25). The appreciation of “one of us coming back to help the rest” was a strong motivator for class attendance. These underlying beliefs and values (i.e., attitudes) affect intention. Intervention modifications that are reflective of participants’ attitudes may result in improved dietary outcomes. As a result of these findings, motivational interviewing, which is a collaborative guide to identify and reinforce motivation for behavior change (26), will be incorporated into subsequent interventions in this region. Motivational interviewing is unique from other counseling and educational strategies in that it seeks to elicit the individual’s own motivation and commitment (26). Cultural awareness and sensitivity are important components when addressing ambivalence to behavior change in this region with longstanding food traditions and consistent poverty. Interview personnel will be either from the Appalachian region or will have worked extensively with individuals native to Appalachia.

An additional finding of this study was the role family members played in the willingness to try new recipes. Future interventions would benefit from an assessment of family members’ food preferences and how receptive they are to trying new recipes. While some participants’ families looked forward to trying new foods, others met with resistance. Including family members in the formative development of interventions may allay this additional barrier to healthy eating. In other regions, awareness of family structure and dynamics should precede and be reflected in intervention development.

Not only should interventions reflect solutions to the cultural and socioeconomic barriers but should also provide the individual with the knowledge that certain behavior changes have resulted in sustained health outcomes even when environmental barriers are unchanged. Interventions that empower the individual to overcome the barriers to healthy eating must address the influence of poverty, limited access, literacy and historical tradition of food preservation. The cooking skills classes gave participants and their families an opportunity to try new recipes without the risk of food waste. In this austere environment, participants reported this opportunity as one of the most beneficial aspects of the classes.

Generalizability of these findings is limited by the low number of cooking class participants. A small number of participants was purposively recruited because this was a pilot to determine feasibility of a subsequent multi-county nutrition intervention. Despite the low number of class participants, the nominal group sessions conducted prior to intervention development revealed barriers and enhancements to healthy eating that paralleled motivation to participate in cooking classes (13). Subsequent focus group research in Appalachia has reported similar findings (27). Additional qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies reflect the importance of pre-intervention assessment of the barriers to and facilitators of healthy eating in several populations worldwide (28–39). While this study was conducted in rural Appalachia, findings are similar to studies conducted in other rural, impoverished regions where geographical isolation limits access to healthy foods.

Lifestyle behavior change interventions should also be based on the individual’s perceived value of dietary behavior change. The Theory of Planned Behavior provides the framework to 1) assess the individual’s perception of the value of behavior change, 2) design individualized intervention components that target that particular value, and 3) develop outcomes and evaluation criteria based on each individual’s rationale for wanting to change behavior. By identifying why individuals want to change their diets and recognizing the most valued intrinsic reward for behavior change, interventions can be developed that empower individuals to change their diets in spite of the many barriers to healthy eating that exist in rural food deserts.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research Grant # 1K23NR014883-01. We are very grateful to Martha Yount, Heather Spencer, and Cheryl Witt for their contributions to this study. We thank Drs. Debra Moser and Deb Reed for guidance during this project.

References

- 1.American Heart Association. [Accessed August 26, 2013];Healthy Diet Guidelines. 2011 http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/NutritionCenter/HealthyCooking/Healthy-Diet-Guidelines_UCM_430092_Article.jsp.

- 2.Sohn M. Food and Cooking. In: Abramson R, Haskell J, editors. Encyclopedia of Appalachia. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press; 2006. pp. 911–961. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savoca MR, Arcury TA, Leng X, Bell RA, Chen H, Anderson A, et al. The diet quality of rural older adults in the South as measured by healthy eating index-2005 varies by ethnicity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009 Dec;109(12):2063–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathematica Policy Research for Feeding America. [Accessed 1 July 2014];Hunger in Central and Eastern Kentucky. 2010 Available: https://godspantry.org/assets/375/HICEK_2010.pdf.

- 5.Lucan SC, Barg FK, Long JA. Promoters and barriers to fruit, vegetable, and fast-food consumption among urban, low-income African Americans--a qualitative approach. Am J Public Health. 2010 Apr;100(4):631–5. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.172692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Withall J, Jago R, Cross J. Families’ and health professionals’ perceptions of influences on diet, activity and obesity in a low-income community. Health Place. 2009 Dec;15(4):1078–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrovici DA, Ritson C. Factors influencing consumer dietary health preventative behaviours. BMC Public Health. 2006 Sep;1(6):222. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DiBonaventura M, Chapman GB. The effect of barrier underestimation on weight management and exercise change. Psychol Health. 2008 Jan;13(1):111–22. doi: 10.1080/13548500701426711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kapur K, Kapur A, Ramachandran S, Mohan V, Aravind SR, Badgand M, et al. Barriers to changing dietary behavior. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008 Jan;56:27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ajzen I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Withall J, Jago R, Cross J. Families’ and health professionals’ perceptions of influences on diet, activity and obesity in a low-income community. Health & Place. 2009 Dec;15:1078–85. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrovici DA, Ritson C. Factors influencing consumer dietary health preventative behaviours. BMC Public Health. 2006 Sep 1;6:222–34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Department of Health and Human Services. Gaining consensus among stakeholders through the nominal group technique. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. Evaluation Brief #7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardin-Fanning F. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet in a rural Appalachian food desert. Rural Remote Health. 2013 Apr-Jun;13:2293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Correa NP, Gor BJ, Murray NG, Mei CA, Baun WB, Jones LA, Sindha TF. CAN DO Houston: A community-based approach to preventing childhood obesity. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010 Jul;7(4):A88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dharod JM, Drewette-Card R, Crawford D. Development of the Oxford Hills Healthy Moms project using a social marketing process: A community-based physical activity and nutrition intervention for low-socioeconomic-status mothers in a rural area in Maine. Health Promot Pract. 2010 Mar;12(2):312–21. doi: 10.1177/1524839909355521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wrieden WL, Anderson AS, Longbottom PJ, Valentine K, Stead M, Caraher M, Dowler E. The impact of a community-based food skills intervention on cooking confidence, food preparation methods and dietary choices – an exploratory trial. Public Health Nutr. Feb;10(2):203–11. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007246658. 3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dombrowski SU, Sniehotta FF, Avenell A, Johnston M, MacLennan G, Araujo-Soares V. Identifying active ingredients in complex behavioural interventions for obese adults with obesity-related comorbidities or additional risk factors for comorbidities: a systematic review. Health Psychol Review. 2012 Dec;6(1):7–32. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor N, Conner M, Lawton R. The impact of theory on the effectiveness of worksite physical activity interventions: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Health Psychol Review. 2012 Mar;6(1):33–73. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson-Bill ES, Winett RA, Wojcik JR. Social cognitive determinants of nutrition and physical activity among web-health users enrolling in an online intervention: the influence of social support, self-efficacy, outcome expectations, and self-regulation. J Med Internet Res. 2011 Mar 17;13(1):e28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zoellner J, Krzeski E, Harden S, et al. Qualitative application of the theory of planned behavior to understand beverage consumption behaviors among adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012 Nov;112(11):1774–784. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ajzen I, Madden TJ. Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions and perceived behavioral control. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1986;22(5):453–74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hardin-Fanning F, Gokun Y. Gender and age are associated with healthy food purchases via grocery voucher redemption. Rural Remote Health. 2014;14(3):2830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burns SL, Scott SL, Thompson DJ. Family and Community. In: Abramson R, Haskell J, editors. Encyclopedia of Appalachia. Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press; 2006. pp. 149–54. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoenberg NE, Howell BM, Swanson M, Grosh C, Bardach S. Perspective on healthy eating among Appalachian residents. J Rural Health. 2013 Aug;29(Suppl 1):s24–34. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterson J, Schmer C, Ward-Smith P. Perceptions of Midwest rural women related to their physical activity and eating behaviors. J Community Health Nurs. 2013;30(2):72–82. doi: 10.1080/07370016.2013.778722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vangeepuram N, Carmona J, Arniella G, Horowitz CR, Burnet D. Use of focus groups to inform a youth diabetes prevention model. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2015 Sep 23; doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2015.08.006. pii: S1499–4046(15)00631-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamran A, Azadbakht L, Sharifirad G, Mahaki B, Mohebi S. The relationship between blood pressure and the structures of Pender’s health promotion model in rural hypertensive patients. J Educ Health Promot. 2015 Mar 27;4:29. doi: 10.4103/2277-9531.154124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inskip H, Baird J, Barker M, Briley AL, D’Angelo S, Grote V, Koletzko B, Lawrence W, Manios Y, Moschonis G, Chrousos GP, Poston L, Godfrey K. Influences on adherence to diet and physical activity recommendations in women and children: Insights from six European studies. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64(3–4):332–9. doi: 10.1159/000365042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sedibe HM, Kahn K, Edin K, Gitau T, Ivarsson A, Norris SA. Qualitative study exploring healthy eating practices and physical activity among adolescent girls in rural South Africa. BMC Pediatr. 2014 Aug 26;14:211. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skinner K, Hanning RM, Tsuji LJ. Barriers and supports for healthy eating and physical activity for First Nation youths in northern Canada. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2006 Apr;65(2):148–61. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v65i2.18095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuta E, Sudo N, Kato N. Barriers to compliance with the Daily Food Guide for Children among first-grade pupils in a rural area in the Philippine Island of Mindanao. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008 Apr;62(4):L 502–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaiser BL, Brown RL, Baumann LC. Perceived influences on physical activity and diet in low-income adults from two rural counties. Nurs Res. 2010 Jan-Feb;59(1):67–75. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0b013e3181c3bd55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yousefian A, Leighton A, Fox K, Hartley D. Understanding the rural food environment –perspectives of low-income parents. Rural Remote Health. 2011;11(2):1631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heuman AN, Scholl JC, Wilkinson K. Rural Hispanic populations at risk in developing diabetes: Sociocultural and familial challenges in promoting a healthy diet. Health Commun. 2013;28(3):260–74. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.680947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verstraeten R, Van Royen K, Ochoa-Aviles A, Penafiel D, Holdsworth M, Donoso S, Maes L, Kolsteren P. A conceptual framework for healthy eating behavior in Ecuadorian adolescents: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2014 Jan 29;9(1):e87183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jahns L, McDonald L, Wadsworth A, Morin C, Liu Y, Nicklas T. Barriers and facilitators to following the Dietary Guidelines for Americans reported by rural, Northern Plains American-Indian children. Public Health Nutr. 2015 Feb;18(3):482–9. doi: 10.1017/S136898001400041X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]