Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of occlusion therapy in the control of intermittent exotropia (IXT) in children between 4 and 10 years in Saudi Arabia. This study will highlight the importance of patching IXT patients and assist to approach the proper use of occlusion therapy.

Methods

A clinical, prospective cohort pilot study was performed on 21 untreated IXT patients. Evaluation of the deviation angle, amplitudes, stereopsis and control before, during and after occlusion therapy was performed.

Results

Eleven percent of the subjects demonstrated a decrease in the deviation angle by 50% while 55.5% attained normal ranges for base-out fusional amplitudes and 77% attained success for the control.

Conclusion

We suggest that alternate occlusion therapy can improve the sensory status and strengthen the fusional amplitudes but does not improve the deviation angle and therefore is useful to postpone surgery in young children and may improve surgical outcome.

Keywords: Intermittent exotropia, Antisuppression therapy, Occlusion therapy, Patching

Introduction

Exotropia is an eye condition where the two eyes are not aligned along the same axes, but instead the axes diverge. Intermittent exotropia (IXT) is an exodeviation intermittently controlled by fusional mechanisms and spontaneously breaks down into a manifest exotropia. At other times the eyes are aligned and binocular single vision is maintained.1

Treatment of exodeviations is indicated if the patient is symptomatic and binocular function is affected. Surgical or non-surgical treatments aim to reduce episodes of manifest exotropia by reducing the angle of deviation and improving control of fusion.2 The decision to perform surgery remains a contentious issue and each case has specific indications including the age of the patient, angle of deviation, symptoms, cosmesis, fusion potential, history, onset, and prognosis. The reasons for non-surgical correction also vary, including patients who want to avoid surgery and clinicians/patients who want to delay surgical intervention for clinical/personal reasons.3 Occasionally non-surgical treatment alleviates symptoms such that surgical invention is unnecessary.3 Occlusion therapy is considered an antisuppression therapy to prevent or eliminate suppression and to induce diplopia in some cases and therefore stimulate motor fusion. However, not all patients complain of diplopia in antisuppression therapy.2 Part-time or full-time occlusion of the dominant eye, or alternate occlusion in patients without ocular preference, has been used for this therapy. In this study, we initiated antisuppression (occlusion) therapy in an attempt to remove the suppression mechanism present under binocular conditions and therefore stimulate and/or improve binocularity by the end of treatment.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of occlusion therapy in the control of IXT and the angle of deviation in children between 4 and 10 years old in Saudi Arabia. To our knowledge, occlusion therapy has not been studied extensively in the literature and to address this gap, the objective of the current study was to provide clear methodology and success criteria for this type of therapy.

Materials and methods

A clinical, prospective cohort pilot study was performed. Thirty-six children were initially enrolled and 21 were able to complete the study. The 21 children were from 4 to 10 years old and had untreated IXT. The angle of the divergence and the child’s ability to control the deviation were measured and compared before, during and after antisuppression (occlusion) therapy. The before and after test results were statistically analyzed in order to assess the effectiveness of occlusion therapy on IXT.

We included patients with diagnosed near and/or distance IXT of at least 10 PD, age range between 4 and 10 years and no amblyopia or history of previous ocular treatment and any coexisting ocular pathology.

Patients’ testing was performed in a standardized manner to minimize dissociation of the eyes. We evaluated the deviation angle at distance and near, stereopsis at distance and near, base-out fusional amplitudes at distance and near, binocular visual acuity and the control score scale. Control score scale was assessed by the office based scale as described by Mohney and Holmes.4

The treatment regimen of occlusion was 50% of waking hours which is about 6 h a day of alternate occlusion. Each patient was assessed at four consecutive month intervals during occlusion treatment plus reassessment after one month without occlusion treatment.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software version 17.0 and MedCal version 8.0. Descriptive and analytical statistics were performed. The Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare means for successive follow-ups. General linear model analysis of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures was used to determine differences between follow-up visits. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Success for the deviation was indicated by a 50% decrease in the deviation angle at near and distance. Success for stereopsis at near was 40 s of arc, and for stereopsis at distance success was 60 s of arc which are considered within the normal range. Success for base-out fusional amplitudes at near was 35 PD and 20 PD for distance which are considered within the normal range.5 Success for binocular visual acuity was 0 LogMAR or better. Success for the control score scale was a rating of 0 or 1 for the distance and near control score.

Thirty-six IXT patients were enrolled in this study; fifteen patients did not attend after the first follow-up visit and were therefore excluded from the study. Twenty-one patients attended all the follow-up visits; yet, three did not complete the full duration of therapy and stopped during the second or third follow-up visits. Eighteen patients completed the full therapy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cohort demographics and refractive error of intermittent exotropes who underwent occlusion therapy.

| Variable | Mean | Standard Deviation | Min. range | Max. range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 8.50 | 1.47 | 6.00 | 10.00 |

| Age of onset | 4.70 | 1.59 | 2.00 | 7.00 |

| OD SE | −1.25 | 1.30 | −3.80 | 0.37 |

| OS SE | −1.29 | 1.24 | −3.75 | 0.25 |

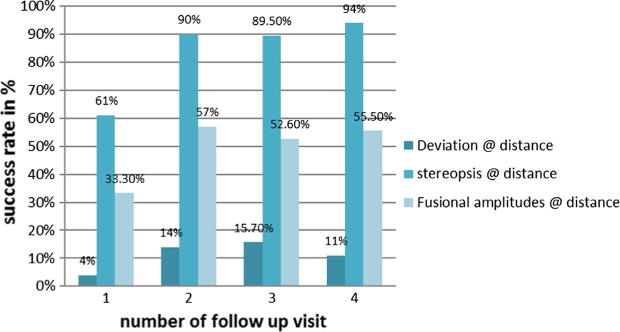

For individual deviation interpretation at distance, only three patients achieved success where the deviation decreased by 50% at the completion of the treatment while two patients (11%) attained success after the treatment visit and the success rate throughout the four follow-up visits was 4% (1/21), 14% (3/21), 15.7% (3/19) and 11% (2/18) for the second visit, third visit, fourth visit and fifth visit respectively. Although significant changes for the deviation at distance occurred at the first visit to the fourth and the first visit to the fifth visit, we will rely on our individual interpretation as it reflects a more detailed evaluation of our data for every individual throughout the five visits. The statistical analysis calculated the mean value of the deviation angle for all the patients in every visit and compared them as an average which reduces the accuracy of the statistical findings. According to our individual interpretation, a low success rate was reported for deviation measurements at distance after the end of the treatment. However, for individual interpretation of deviation at near, success was achieved in 44.4% of the eighteen patients who completed the full duration of treatment at their last visit (fifth visit) and there were significant changes when comparing the first visit to the fourth visit and the first visit to the fifth visit.

The success rate for stereopsis at distance was high starting from the third visit to the last visit. The minor differences between the third to the fifth visits in stereopsis at distance explain lack of significance between visits. Additionally, 27.7% of the patients were within normal stereoacuity at the outset which indicates there was little room for improvement in approximately a third of the cases and therefore this may explain the lack of statistical significance calculated by the Wilcoxon signed rank test. However, individual interpretation indicated a success rate of 94% at the last visit where 17 cases out of eighteen improved to normal stereoacuity. More than 50% of the subjects had normal near stereoacuity at the first visit which left little room for improvement and therefore warranted minor discussion or analysis.

Base-out fusional amplitudes at distance attained successful levels in 55.5% of the cases. The difference between the first and fourth visits and first visit and fifth visit was significant (P = 0.000, both comparisons). There were no significant differences between other visits (P > 0.05, all comparisons). In reviewing the data individually throughout the four follow-up visits, results of the fusional amplitudes measures were very similar during successive visits starting from the second follow-up visit. Sixteen out of nineteen patients had within 5 PD changes from visit three to visit four and seventeen patients out of eighteen had within 5 PD changes from visit four to visit five. This may explain the lack of significance between these visits. Additionally, Fig. 1 plots the improvement between the first follow-up visit to the second follow-up while smaller differences occur between subsequent visits indicating the little room for improvement at last visit. Base-out fusional amplitude at near results improved successfully in 94.4% of our cases. However, only the first (P = .001) and second (P = .003) follow-ups were statistically significant. When data were reviewed, eleven patients had within 5 PD changes from visit three to visit four and ten patients had 5 PD changes from visit four to visit five which explains the lack of significant change as these values were slightly more than 50% of the cases. In addition, significant improvement was attained comparing the first visit to the fourth (P = .000) and to the fifth (P = .001) follow-up visits.

Figure 1.

The change in success rate from one visit to the successive visit for deviation at distance, distance stereopsis and base-out fusional amplitudes at distance of intermittent exotropes who underwent occlusion therapy.

Successful binocular visual acuity was attained in 94.4% of our cases with significant improvement between the first visit to the fourth visit (P = .001) and the fifth (P = .001) follow-up visits. There was significant change in the first follow-up as well (P = .002). Individual analysis indicates the consistency of the data from one visit to another which explains the lack of significance in the second (P = .221), third (P = .109) and fourth (P = .317) follow-up visits.

Data for the control score scale at distance indicated a 77.7% success rate. Significant changes occurred between the first visit to the fourth (P = .002) and to the fifth (P = .015) visits. There was a significant difference in the first (P = .006) follow-up. Individual analysis of the data indicates the consistency of the data between the remaining follow-up visits explaining the lack of statistical significance for the second (P = .206), third (P = .206) and fourth (P = .257) follow-up visits.

There was a 100% success rate for the control score scale at near. There was a significant difference between the first visit to the fourth (P = .003) and the fifth (P = .001) visits. There was a significant difference in the first (P = .001) and second (P = .046) follow-up visits as well. In the remaining follow-up visits, consistency of the data is evident from visit to visit when the data are individually evaluated. This consistency explains the lack of significance.

Discussion

All of our variables under study indicated moderate to high success except for the deviation angle at distance. Near stereoacuity was excluded from this analysis as discussed above. Our distance deviation findings are similar to those reported by Figueira and Hing6 who treated their subjects with occlusion therapy alone for near and distance and reported rates of 6% (3/50), 8.57% (3/35), 5.26% (1/19) and 0% (0/5) at 6 months, 1, 2 and 5 year follow-ups, respectively, with no significant difference. Due to the differences in the clinical testing methods, comparison of other variables between our study and Figueira and Hing’s study is not possible. Our results concur with Reynolds and Wackerhagen7 who reported 6% of their patients achieved a persistent improvement in angle size. Similarly, Flynn, MeKenney and Rosenhouse8 reported a 68% success rate for sensory and motor effects of occlusion therapy where the fusional ranges increased, the diplopia awareness improved and the control of the deviation improved as well. Alternately, 39% of the cohort in the Flynn, et al. study worsened in the size and frequency of the deviation. Asbury9 found that 94% of subjects obtained stereopsis with enhanced fusional vergence amplitudes at near and distance which agrees with our findings.

Contrary to our observations, Suh et al.10 found that part-time occlusion therapy resulted in a significant reduction of the deviating angles at distance. However the data for near deviation in the Suh et al. study concur with our results. Similarly, 27% of patients in the Freeman and Isenberg11 study became orthophoric and 45.5% had an asymptomatic exophoria at the last examination which differs from our deviation angle results at distance. Furthermore, Iacobucci and Henderson12 showed a beneficial effect of occlusion therapy on exodeviations, both in pattern type and size of deviation which also disagrees with our results for deviation at distance. In addition, Spoor and Hiles13 reported an improvement in 54% in the deviation angle at distance and concluded that occlusion therapy decreases the size of the deviation. However, Berg, Lozano and Isenberg14 found that occlusion therapy decreases deviation angle at near (77%) and distance (56%). Newman and Mazow15 found that 87% of their subjects who were treated with occlusion therapy reported decrease in the deviation size or converted to phoria which differs from our findings.

Few studies concur with some of our results but not all our results. Other studies however used different methodology than ours and compared occlusion therapy to other treatment modalities. Cooper and Leyman16 found that occlusion therapy is useful in breaking down suppression with 63% of the cohort who were treated with occlusion therapy showing fair to good results for deviation angle, stereopsis and fusional amplitudes which partially agrees with our results in the stereopsis and fusional amplitudes part only. Chutter17 found that the size of the deviation decreased after treatment application which differs from our findings but the fusional ranges were improved and the fusional recovery (control) was strengthened which is similar to our findings.

We aimed at the end of our research to answer the following questions:

-

1.

Does antisuppression therapy improve control in non-diplopic patients with intermittent exotropia?

-

2.

Are the benefits of treatment stable one month after cessation of treatment?

Conclusion

In conclusion, this prospective pilot study of IXT patients treated with alternate antisuppression occlusion therapy suggests that alternate occlusion therapy can improve the sensory status and strengthen the fusional amplitudes at near and distance. In addition, we suggest that occlusion therapy can improve the deviation control but does not improve the size of the angle of deviation although it does not worsen it. At the end of our study we can answer the Study question 1. Does antisuppression therapy improve control in non-diplopic patients with intermittent exotropia? Yes, but not the size of deviation. Study question 2. Are the benefits of treatment stable one month after cessation of treatment? Improved success rates occurred over consecutive visits for fusional amplitudes, stereopsis and deviation control and final levels were maintained at one month after final therapy except for the angle of deviation.

Ethical compliance statement

This project has been approved by the Dalhousie University ethical committee and King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital ethical committee and subjects signed an informed consent to their participation in this study.

Financial support

No financial support was involved in this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are extended to the faculty of the Clinical Vision Science Program at Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada, for the ongoing motivation given and for building up the skills academically and clinically; and to the colleagues and mentors at the King Khaled Eye Specialist Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. A note of thanks is also extended to my beloved family for always being by my side.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Saudi Ophthalmological Society, King Saud University.

References

- 1.Ansons A.M., Davis H. Diagnosis and management of ocular motility disorders. Blackwell; Oxford: 2001. Exotropia. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Von Noorden G.K., Campos E.C. Exodeviations. In: von Noorden G.K., editor. Binocular vision and ocular motility: theory and management of strabismus. Mosby; St. Louis: 2002. pp. 356–376. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karlsson V. Does nonsurgical treatment of exodeviation work? Am Orthoptic J. 2009;59:18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohney B.G., Holmes J.M. An office based scale for assessing control in intermittent exotropia. Strabismus. 2006;14:147–150. doi: 10.1080/09273970600894716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright K.W., Spigel P.H. Binocular vision and introduction to strabismus. In: Wright K.W., editor. Pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. Springer; New York: 2003. p. 154155. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figueira E.C., Hing S. Intermittent exotropia: comparison of treatments. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;34:245–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds J.D., Waackerhagen M. Early onset exodeviations. Am Orthoptic J. 1988;38:94–100. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flynn J.T., MeKenney S., Rosenhouse M. Management of intermittent exotropia. In: Moor S., Mein J., Stockbridge L., editors. Orthoptics: past, present, future. Medical Publishers; Chicago: 1976. pp. 551–557. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asbury T. The role of orthoptics in the evaluation and treatment of intermittent exotropia. In: Arruga A., editor. International strabismus symposium. Karger; New York: 1968. pp. 331–338. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suh Y.W., Kim S.H., Lee J.Y., Cho Y.A. Conversion of intermittent exotropia types subsequent to part-time occlusion therapy and its sustainability. Von Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:705–708. doi: 10.1007/s00417-005-0195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman R.S., Isenberg S.J. The use of part-time occlusion for early onset unilateral exotropia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1989;26:94–96. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19890301-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iacobucci I., Henderson J.W. Occlusion in the preoperative treatment of exodeviations. Am Orthoptic J. 1965;15:42–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spoor D.K., Hiles D.A. Occlusion therapy for exodeviations occurring in infants and young children. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:2152–2157. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(79)35295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg P.H., Lozano M.J., Isenberg S.J. Long term results of part time occlusion for intermittent exotropia. Am Orthoptic J. 1998;48:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Newman J., Mazow M.L. Intermittent exotropia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1956;55:484487. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper J., Medow N. Intermittent exotropia, basic and divergence excess type. Binocular Vision Eye Muscle Surgery. 1993;8:185–216. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chutter C. Occlusion treatment of intermittent divergent strabismus. Am Orthoptic J. 1977;27:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]