How should doctors present case reports? Medical tradition, our mentors and our textbooks teach a standard format that starts with identifying information, followed by the chief complaint, history of present illness (HPI), past history, medications, social and family history, and review of systems, with slight variations in the ordering or categorization of some elements.1 Some clinicians dislike this format because they feel that important information contained in the past history and review of medications is given too little attention, too late. Consequently, a new approach to case reports has developed in which the HPI is the final element. An informal poll of internal medicine program directors indicates that this new method is prevalent in Toronto and Vancouver, whereas the traditional format prevails elsewhere. We argue that neither approach is optimal and recommend a third alternative that stresses the patient's story of illness and engages the doctor's capacity to understand, interpret and communicate the meaning of that story.2 We term this the “storied case report” in recognition of the importance of narrative to the case report.

Consider a patient with jaundice who receives testosterone injections, has used alcohol extensively and has chronic hepatitis B. When the traditional case report format is rigidly adhered to, these data elements are recorded in the medication, social history and past medical history sections respectively. Critics rightly point out that the resulting report lacks a logical flow, and advocates of the second, “HPI-last” approach encourage trainees to present these facts early in the case presentation so that the HPI can be interpreted in light of known information.

If evidence indicated that the HPI-last format resulted in more complete recording of information and improved communication, or if it boosted the diagnostic yield of history taking, we would put aside our reservations. In the absence of such evidence, however, we have 3 objections to it. First, it is excessively mechanical. As with the traditional format, the HPI-last approach compartmentalizes the patient's history into rigid categories without drawing the connections, a regrettable example of how easily data reporting can be divorced from information synthesis. Consequently, when using the new format, even a brilliant presenter may appear to have muddled and disjointed thought processes. As one expert clinician has stated, “Simply to write down or to recite a gaggle of true statements is not to compose a history. The facts must be placed in a form that makes them informative.”1 What's lost is the “narrative text”: the doctor's interpretation and retelling of the patient's history.3

Our second objection is that the HPI-last format may impede effective diagnosis. Emphasizing facts that are irrelevant to the current problem can lead to cognitive errors as the listener is presented with distracting or misleading data. Studies of how expert clinicians formulate differential diagnoses indicate that they consider just a few possibilities simultaneously, generate hypotheses early and often make the mistake of fitting data presented late in the case report to these early hypotheses.4,5 A strategy to help clinicians avoid diagnostic errors would present the most salient information early in the case report and keep less relevant information for later.

Our third and most important objection to presenting the HPI last is that it undermines the telling of stories. This is true of both the physician's interpretative story of the patient's history and the patient's own “experiential text” — the meanings and existential qualities that patients assign to their symptoms and diagnoses.3 Presenting the HPI early is consistent with the aims of narrative medicine, which emphasizes the patient's experiences and circumstances,6,7 and, advocates believe, is therefore more empathic. Narrative medicine aids the physician in that it is in hearing stories that, knowingly and subconsciously, we start the intellectual processes of prediction, evaluation, planning and explanation.7,8 Aesthetic considerations aside, the case report should more closely resemble the linear structure of a film by Frank Capra than the fractured storyline of one by David Lynch.

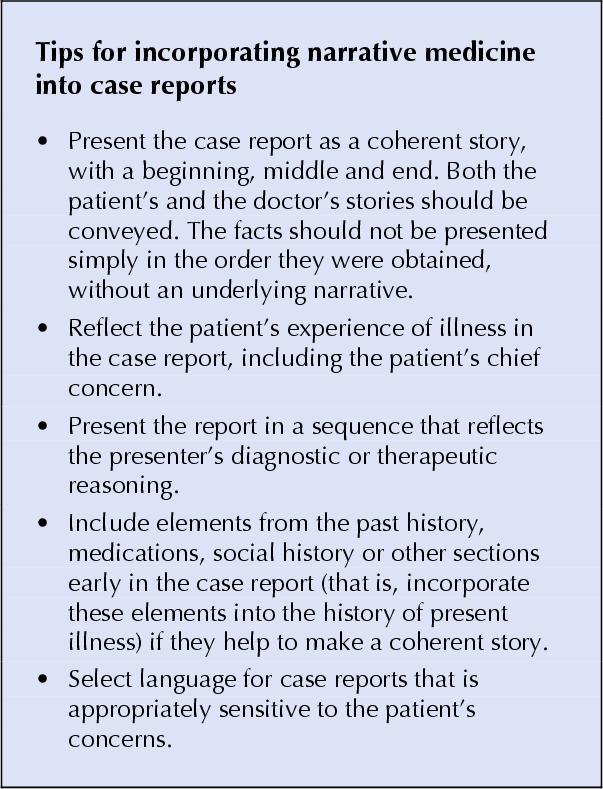

We suggest teaching trainees to present case reports as the telling of 2 interrelated stories: the patient's (of illness) and the doctor's (of diagnosis and treatment). In doing so, we stress 5 principles. First, the order in which data are presented should reflect these stories, rather than the sometimes chaotic circumstances of data collection. Second, the case report should reflect the patient's experience of his or her illness, for example by including the patients' chief complaint (or chief concern9) rather than the regrettably common “reason for referral.” Third, the case report should reflect the logic of the presenter's diagnostic or therapeutic reasoning. Fourth, the HPI should be extended to include all elements relevant to understanding the patient's current problem, regardless of the section in which they are ordinarily recorded; hence the “H” in HPI. We urge presenters to include phrases such as “Of relevance in the past medical history …” or “The family history is pertinent because …” in the HPI. Fifth, the language of case reports should be suitable for telling stories and sensitive to patients' experiences.9,10

Our advocacy of the storied case report has not been very successful on the wards. Perhaps junior trainees find it too hard to determine what is relevant and senior trainees find it too hard to change their habits. Although we are convinced that approaching the case report as a narrative will make the bedside encounter more scientific (yielding an improved evidence base and structure for making diagnoses) and more artful (yielding an enhanced understanding of the patient's perspectives and needs), we admit that this hypothesis is difficult to test. Perhaps the best argument for such an approach lies in the fundamental human tendency to tell stories and the essential humanism therein.

Ahmed M. Bayoumi Inner City Health Research Unit St. Michael's Hospital Peter A. Kopplin Department of Medicine University of Toronto Division of General Medicine St. Michael's Hospital Toronto, Ont.

Figure.

References

- 1.Sapira JD. The art and science of bedside diagnosis. Baltimore: Urban and Schwarzenberg; 1990.

- 2.Charon R. Narrative medicine: form, function, and ethics. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:83-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Greenhalgh T. Narrative based medicine: narrative based medicine in an evidence based world. BMJ 1999;318: 323-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Sox HC, Blatt MA, Higgins MC, Marton KI. Medical decision making. Boston: Butterworths; 1988.

- 5.Kassirer JP. Diagnostic reasoning. Ann Intern Med 1989;110:893-900. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Charon R. The patient–physician relationship. Narrative medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession and trust. JAMA 2001;286: 1897-902. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B. Narrative based medicine: why study narrative? BMJ 1999;318:48-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Turner M. The literary mind. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996.

- 9.Donnelly WJ. The language of medical case histories. Ann Intern Med 1997; 127:1045-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Bayoumi AM, Bravata D. The language of case histories. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:876-8. [DOI] [PubMed]