Abstract

The incidence of resistance against fluoroquinolones among pathogenic bacteria has been increasing in accordance with the worldwide use of this drug. Escherichia coli is one of the most relevant species for quinolone resistance. In this study, a diagnostic microarray for single-base-mutation detection was developed, which can readily identify the most prevalent E. coli genotypes leading to quinolone resistance. Based on genomic sequence analysis using public databases and our own DNA sequencing results, two amino acid positions (83 and 87) on the A subunit of the DNA gyrase, encoded by the gyrA gene, have been identified as mutation hot spots and were selected for DNA microarray detection. Oligonucleotide probes directed against these two positions were designed so that they could cover the most important resistance-causing and silent mutations. The performance of the array was validated with 30 clinical isolates of E. coli from four different hospitals in Germany. The microarray results were confirmed by standard DNA sequencing and were in full agreement with phenotypic antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Quinolones are among the most potent antibacterial agents used in human therapy. Fluoroquinolones have been widely applied as broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents in clinical medicine since 1983. With the worldwide use of this drug, the corresponding resistance among bacteria has increased significantly. One of the most relevant species is Escherichia coli, in particular for urinary tract infections, where E. coli is the infection-causing pathogen in 80% of cases. In clinical routine, 90% of these kinds of infections are treated with quinolone antibiotics. However, 7 to 9% of the pathogenic E. coli isolates are quinolone resistant and cause clinical complications (M. Susa, unpublished data). In addition, quinolone-resistant E. coli could be a potential threat to neutropenic patients with leukemia who receive a quinolone as prophylaxis (36). The molecular background of quinolone resistance is missense mutations (single-nucleotide exchanges) in the target enzyme genes and, less importantly, the reduction of quinolone accumulation inside the cells (2, 10, 16, 22, 27). In gram-negative organisms, such as E. coli, the primary target of fluoroquinolones is the DNA gyrase (3, 11). Missense mutations in the A subunit of the DNA gyrase are commonly considered to be the main reason for quinolone resistance in E. coli (8, 9, 28, 30). Such single-nucleotide exchanges are clustered in a small region called the quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) (5, 27, 37). Up to now, the standard methods to determine antibiotic resistance, e.g., disk diffusion tests or E-tests, have been based on phenotypic identification; these methods are time-consuming, are culture-based, and have room for improvement in terms of sensitivity and precision. A rapid and precise genotype-based diagnostic resistance test would be of great value for the clinic. Although several molecular genetic methods, such as single-stranded conformational polymorphism (SSCP) analysis (25), mismatch amplification mutation assay (MAMA) (29), and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis (12), have been used to investigate QRDRs of gyrA, all of them have limitations in different aspects and are not yet established in clinical routine diagnostics of microbial antibiotics resistance. As an example, SSCP can detect only the region of the missense mutation and not the exact position of the missense mutation, MAMA can either detect one genotype or requires the use of multiplex PCR, and RFLP can detect missense mutations inside the recognition sequence of the restriction enzyme but not the exact position and the substitution. In contrast, DNA microarray technology provides a promising alternative for high-throughput genotype-based diagnostics. The potential of miniaturization and multiplexing offers a considerable advantage over other molecular genetic methods for clinical application, which could be demonstrated, for example, in the case of DNA microarray-based assays developed for the detection of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium (20, 21, 33). Although a system for the detection of ciprofloxacin-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae was also developed recently (4), there is no such assay for the detection of quinolone-resistant E. coli, which is one of the most relevant species.

In this study, we developed a microarray-based genotyping method to detect quinolone resistance in a short time and to cover different E. coli genotypes. Based on allele frequency analysis using public databases and in-house DNA sequencing of clinical E. coli isolates, two amino acid positions (83 and 87) in the gyrase A subunit were identified as hot spots for the detection of quinolone resistance. Although there are several platforms available for array-based single-nucleotide polymorphism, e.g., allele-specific hybridization (34), single-base primer extension (26), allele-specific amplification (1), or allele-specific oligonucleotide ligation (13), we chose allele-specific hybridization because its robust performance should be suitable for routine clinical application. In contrast to the above-mentioned genotyping methods, the use of allele-specific hybridization allowed not only the identification of the mutated amino acid but also the exact substitution, which could have different contributions to resistance and can be used as a marker in epidemiological studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

In total, 30 E. coli clinical isolates from four different hospitals in Germany (Backnang, Stuttgart, Schorndorf, and Winnenden) (referred to here as E. coli 1 to 30) were used for this study. These strains were isolated from urine (n = 20), swabs (n = 7), secretions (n = 2), and blood (n = 1) of patients. The susceptibility against quinolone was determined according to NCCLS guidelines by using either ciprofloxacin alone (n = 23) or both ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin (n = 7). The genomic DNA was isolated from a bacterial pure culture by using a QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Hilden Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

DNA sequencing.

For the DNA sequencing, a 418-bp fragment of E. coli, which included the QRDRs, was amplified by PCR with primers described previously (35). The 50-μl PCR mixture included approximately 80 ng of template (genomic DNA of E. coli), a 0.4 pM concentration of each primer, 0.25 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1.5 mM Mg2+, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The PCRs were performed in a thermocycler (Mastercycler gradient) (Eppendorf) with the following parameters: 94°C for 5 min; 30 cycles at 94°C for 1 min, 52°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min; and a final elongation at 72°C for 10 min. The amplified fragment, which was purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) according to the manual provided by the manufacturer, was used for direct sequencing. The sequencing was done with the same primer pairs, a Big-Dye terminator cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany), and a Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). For each isolate, two PCR products from separate reactions were sequenced, using both the forward and reverse primers.

Amplification and labeling.

The labeling PCRs were performed with forward primer 5′-ACGTACTAGGCAATGACTGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGAGTCGCCGTCGATGGAAC-3′. The 50-μl PCR mixture included approximately 80 ng of template (genomic DNA of E. coli), a 0.4 pM concentration of each primer, 0.1 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (the ratio between dCTP and Cy5-dCTP was 3:2), 1.5 mM Mg2+, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Eppendorf). The same parameters as described above were used for the labeling PCRs. The amplified 189-bp fragment, which was purified by using a QIAquick PCR purification kit, was used for hybridization.

Array fabrication.

Using a Microgrid II microarrayer (Biorobotics, Cambridge, United Kingdom), the oligonucleotide capture probes (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), which were dissolved in 50% dimethyl sulfoxide at a concentration of 20 μM, were spotted on poly-l-lysine slides (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) in two subarrays. On each slide a spotting control (Cy5-labeled oligonucleotide 5′-Cy5-CTAGACAGCCACTCATA-3′), a hybridization control (5′-GATTGGACGAGTCAGGAGC-3′) complementary to a labeled oligonucleotide target, a negative control (5′-CTAGACAGCCACTCATA-3′), and a process control (an oligonucleotide with the consensus sequence for gyrA, 5′-TAATCGGTAAATACCATCC-3′) were also included. The sequences of the first three controls were unrelated to the bacterium. After spotting, the slides were irradiated with UV light at 120 mJ/m2 by using a UV cross-linker (Biometra, Göttingen, Germany), blocked with a blocking solution (0.18 M succinic anhydride in methylpyrrolidinone-44 mM sodium borate [pH 8.0]) for 10 min, rinsed with distilled water and 98% ethanol, and finally air dried for 10 min.

Hybridization, washing, and scanning.

The purified amplicon in 40 μl of hybridization solution (6× SSPE [1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1mM EDTA {7.7}] and 0.1 pmol of Cy5-labeled DNA complementary to the hybridization control) was incubated on poly-l-lysine slides at 45°C for 3 h in hybridization chambers (Corning) in a hybridization oven (OV5; Biometra, Göttingen, Germany). For hybridization, 4 pmol target of DNA was used. After hybridization, the slides were washed with 2 ×SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)-0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 15 min and with 0.2× SSC for 3 min at room temperature and subsequently were dried with N2.

Image acquisition and data processing.

Data from hybridized oligonucleotide arrays were extracted by acquisition of fluorescence signals with a 418 array scanner (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, Calif.), using 100% laser power and 100% gain. The image processing and calculation of signal intensities were performed with ImaGene, version 3.0 (Biodiscovery Inc., Los Angeles, Calif.). For the calculation of the individual net signal intensities, the local background was subtracted from the raw spot intensity value. The raw data were saved as plain-text files and processed by using Excel. The perfect match (PM) intensity (highest intensity among four probes for one single-nucleotide polymorphism) and the ratio between PM and mismatch (MM) (intensity of PM/mean intensity of MM) were used for resistance detection. For further process automation, an analysis tool was developed (X. L. Yu, R. D. Schmid, and T. T. Bachmann, unpublished data).

RESULTS

Allele frequency analysis.

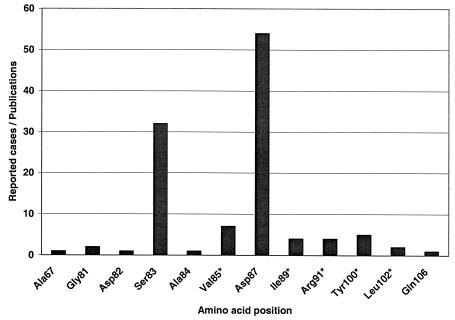

With a homology search in GenBank (National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI]) 21 sequences of E. coli gyrA which were longer than 120 bp and had an E-value (expected threshold, or the statistical significance threshold for reporting matches against database sequences according to the stochastic model of Karlin and Altschul [17]) smaller than 0.15 have been found. The sequence analysis revealed one missense mutation at position 87 for one isolate (accession number Y00544 in GenBank) and two silent mutations at position 84 (accession numbers AE005455 and AP002560) and 85 (accession numbers AE005455, AP002560, and AF052254) for several isolates. In order to obtain additional information, 130 publications from 1985 to June 2003 were analyzed. Altogether, 12 positions (Fig. 1 and Table 1) which contained either missense mutations or silent mutations were found. To ensure a reliable probe design for clinical E. coli strains, five clinical isolates were sequenced. The sequences were in good accordance with the literature data and were included in the probe design.

FIG. 1.

Frequency of reported cases of mutation in the literature according to amino acid position of the A subunit of the E. coli gyrase (gyrA product) (literature data analysis from January 1985 to June 2003 through PubMed of NCBI). Positions with silent mutations are indicated with an asterisk.

TABLE 1.

Previously reported mutations in gyrA QRDRs among E. coli strainsa

| Strain(s) | Codon(s) (amino acid[s]) at amino acid positionb:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 67 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 87 | 89 | 91 | 100 | 102 | 106 | |

| E. coli K-12 | GCC (Ala) | GGT (Gly) | GAC (Asp) | TCG (Ser) | GCG (Ala) | GTC (Val) | GAC (Asp) | ATC (Ile) | CGC (Arg) | TAT (Tyr) | CTG (Leu) | CAG (Gln) |

| Mutants | TCC (Ser) | TGT (Cys), GAT (Asp) | GGC (Gly) | GCG (Ala), TTG (Leu), TGG (Trp), GTG (Val) | CCG (Pro) GCA | GTT | AAC (Asn), CAC (His), TAC (Tyr), GTC (Val), GGC (Gly), GGA (Gly) | ATT | CGT | TAC | TTG | CAT (His) |

From a literature data analysis from January 1985 to June 2003 through PubMed of NCBI.

Underlining indicates nucleotide substitutions compared to E. coli K-12 (GenBank accession number AE000312).

Capture probe design.

All positions containing missense mutations or silent mutations were evaluated based on the frequency of the corresponding publications and their contribution to resistance. Amino acid positions 83 (second position of the codon) and 87 (first and second positions of the codon) turned out to be the most important for quinolone resistance. Consequently, the capture probes were designed against these two positions. All probes were 19 bases long and had various base positions in their centers. The probe sequences are listed in Table 2. As the sequence data analysis revealed strain-associated silent mutations in close vicinity (amino acid positions 85 and 89), two sets of specific probes (8 probes in total) for amino acid position 83 and eight sets of specific probes (32 probes in total) for amino acid position 87 were designed, with four sets directed against the first position of the codon and the other four sets directed against the second position of the triplet. In order to reduce the capture probe numbers in the future, the use of degenerate capture probes was investigated. Universal capture probes with inosine at the sites of these two strain-associated silent mutations at amino acid positions 85 and 89 were designed (one set for amino acid position 83 and two sets for amino acid position 87), which should match all genotypes.

TABLE 2.

Capture probes directed against amino acid positions 83 and 87 of E. coli GyrA, with consideration of silent mutations at amino acid positions 85 and 89

| Name | Position | Silent mutation position (codon) | Sequence (3′ → 5′)a | Amino acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 83A1(Stop) | 83 | 85 (GTC) | AT GGT GAC TAG GCG GTC TA | Stop codon |

| 83T1(Leu) | 83 | 85 (GTC) | AT GGT GAC TTG GCG GTC TA | Leu |

| 83G1(Trp) | 83 | 85 (GTC) | AT GGT GAC TGG GCG GTC TA | Trp |

| 83C1(Ser) | 83 | 85 (GTC) | AT GGT GAC TCG GCG GTC TA | Ser |

| 83A2(Stop) | 83 | 85 (GTT) | AT GGT GAC TAG GCG GTT TA | Stop codon |

| 83T2(Leu) | 83 | 85 (GTT) | AT GGT GAC TTG GCG GTT TA | Leu |

| 83G2(Trp) | 83 | 85 (GTT) | AT GGT GAC TGG GCG GTT TA | Trp |

| 83C2(Ser) | 83 | 85 (GTT) | AT GGT GAC TCG GCG GTT TA | Ser |

| 83AU(Stop) | 83 | 85 (GTI) | AT GGT GAC TAG GCG GTI TA | Stop codon |

| 83TU(Leu) | 83 | 85 (GTI) | AT GGT GAC TTG GCG GTI TA | Leu |

| 83GU(Trp) | 83 | 85 (GTI) | AT GGT GAC TGG GCG GTI TA | Trp |

| 83CU(Ser) | 83 | 85 (GTI) | AT GGT GAC TCG GCG GTI TA | Ser |

| 87A1(Asn) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTC TAT AAC ACG ATT G | Asn |

| 87T1(Tyr) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTC TAT TAC ACG ATT G | Tyr |

| 87G1(Asp) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTC TAT GAC ACG ATT G | Asp |

| 87C1(His) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTC TAT CAC ACG ATT G | His |

| 87A2(Asn) | 87 | 85 (GTT)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT AAC ACG ATT G | Asn |

| 87T2(Tyr) | 87 | 85 (GTT)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT TAC ACG ATT G | Tyr |

| 87G2(Asp) | 87 | 85 (GTT)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT GAC ACG ATT G | Asp |

| 87C2(His) | 87 | 85 (GTT)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT CAC ACG ATT G | His |

| 87A3(Asn) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATC) | GCG GTC TAT AAC ACG ATC G | Asn |

| 87T3(Tyr) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATC) | GCG GTC TAT TAC ACG ATC G | Tyr |

| 87G3(Asp) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATC) | GCG GTC TAT GAC ACG ATC G | Asp |

| 87C3(His) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATC) | GCG GTC TAT CAC ACG ATC G | His |

| 87A4(Asn) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT AAC ACG ATC G | Asn |

| 87T4(Tyr) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT TAC ACG ATC G | Tyr |

| 87G4(Asp) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT GAC ACG ATC G | Asp |

| 87C4(His) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT CAC ACG ATC G | His |

| 87AU1(Asn) | 87 | 85 (GTI)/89 (ATI) | GCG GTI TAT AAC ACG ATI G | Asn |

| 87TU1(Tyr) | 87 | 85 (GTI)/89 (ATI) | GCG GTI TAT TAC ACG ATI G | Tyr |

| 87GU1(Asp) | 87 | 85 (GTI)/89 (ATI) | GCG GTI TAT GAC ACG ATI G | Asp |

| 87CU1(His) | 87 | 85 (GTI)/89 (ATI) | GCG GTI TAT CAC ACG ATI G | His |

| 87A5(Asp) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTC TAT GAC ACG ATT G | Asp |

| 87T5(Val) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTC TAT GTC ACG ATT G | Val |

| 87G5(Gly) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTC TAT GGC ACG ATT G | Gly |

| 87C5(Ala) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTC TAT GCC ACG ATT G | Ala |

| 87A6(Asp) | 87 | 85 (GTT)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT GAC ACG ATT G | Asp |

| 87T6(Val) | 87 | 85 (GTT)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT GTC ACG ATT G | Val |

| 87G6(Gly) | 87 | 85 (GTT)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT GGC ACG ATT G | Gly |

| 87C6(Ala) | 87 | 85 (GTT)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT GCC ACG ATT G | Ala |

| 87A7(Asp) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATC) | GCG GTC TAT GAC ACG ATC G | Asp |

| 87T7(Val) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATC) | GCG GTC TAT GTC ACG ATC G | Val |

| 87G7(Gly) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATC) | GCG GTC TAT GGC ACG ATC G | Gly |

| 87C7(Ala) | 87 | 85(GTC)/89 (ATC) | GCG GTC TAT GCC ACG ATC G | Ala |

| 87A8(Asp) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT GAC ACG ATC G | Asp |

| 87T8(Val) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT GTC ACG ATC G | Val |

| 87G8(Gly) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT GGC ACG ATC G | Gly |

| 87C8(Ala) | 87 | 85 (GTC)/89 (ATT) | GCG GTT TAT GCC ACG ATC G | Ala |

| 87AU2(Asp) | 87 | 85 (GTI)/89 (ATI) | GCG GTI TAT GAC ACG ATI G | Asp |

| 87TU2(Val) | 87 | 85 (GTI)/89 (ATI) | GCG GTI TAT GTC ACG ATI G | Val |

| 87GU2(Gly) | 87 | 85 (GTI)/89 (ATI) | GCG GTI TAT GGC ACG ATI G | Gly |

| 87CU2(Ala) | 87 | 85 (GTI)/89 (ATI) | GCG GTI TAT GCC ACG ATI G | Ala |

Boldface indicates missense mutations; underlining indicates silent mutations.

Microarray testing of clinical isolates.

The performance of each step in the microarray experiments was checked with four types of control probes. A spotting control which was 5′-Cy5 labeled indicated correct spotting and immobilization performance. The hybridization control together with a spiked, labeled complementary oligonucleotide indicated a successful hybridization reaction. The absence of signals for these two controls would have indicated a spotting failure and a disturbance in the hybridization step, respectively. The process control, comprised of a gyrA consensus sequence, was used to monitor the correct function of the labeling PCR and hybridization. The correct washing and the absence of unspecific hybridization was checked with the negative control probe, which was comprised of an Arabidopsis thaliana sequence. If slides showed no signal for the first three controls or a detectable signal for the negative control, they would be excluded from the study.

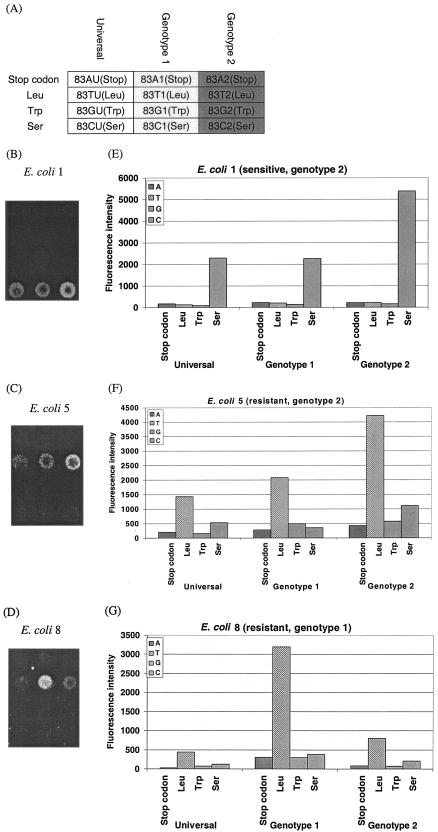

The specificity of the probes and the applicability for clinical isolates were validated by using 30 clinical E. coli isolates, which were isolated from four different hospitals in Germany. Initially, the specificity of the probes was checked by using five sequenced isolates. The final fluorescence intensities showed an array-to-array variation of up to 100%, which was related to the varying labeling efficiency achieved by each PCR and the inconsistency of the fluorescence background evoked by the poly-l-lysine. In order to set the cutoff values for a significant signal for further analysis, repeated experiments with these five isolates were performed. Here, the lowest quantifiable signal associated with a probe spot was found to be 300. To make the chip-based assay reliable, a value of 1,000 was chosen as a cutoff value for the PM intensity. For all five isolates, the discrimination between PM and MM signals could be made with PM/MM ratios above 4. Consequently, the cutoff value for the PM/MM ratio was set to 4. The cutoff values of 1,000 for the signal intensity and 4 for the PM/MM ratio were applied for further experiments using the remaining 25 isolates and were exceeded in all cases. The results of these experiments are shown in Table 3. The microarray results were in agreement with the outcome of the direct DNA sequencing and were in accordance with standard susceptibility testing. Three examples (one sensitive E. coli strain [E. coli 1] and two resistant E. coli strains with different genotypes [E. coli 5 and E. coli 8]) of the missense mutations for position 83 are shown in Fig. 2. The different hybridization patterns on the microarray between quinolone-sensitive and -resistant E. coli and among different E. coli genotypes could be seen clearly. The sensitive E. coli strain showed a signal corresponding with serine (Fig. 2B), while both resistant E. coli strains showed a hybridization signal indicating a leucine at position 83 (Fig. 2C and D). Considering the performance of the different probe sets for one amino acid position, the highest intensity of the sensitive E. coli strain was found for genotype 2 (Fig. 2B), while the genotypes of the two resistant E. coli strains for leucine varied between genotype 1 (Fig. 2D) and genotype 2 (Fig. 2C). The identification could be performed unambiguously, as the intensities of the PM signals were at least five fold higher than that of an MM signal, and the genotype-corresponding PM signals were at least twofold higher than those of the nonmatching probes.

TABLE 3.

Microarray data for 25 clinical isolatesa

| Isolate | Amino acid position 83

|

Amino acid position 87

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM intensity | PM/MM ratio | PM intensity | PM/MM ratio | |

| 1 | 4,217 | 10.8 | 1,494 | 7.1 |

| 7 | 16,802 | 5.0 | 3,377 | 13.0 |

| 8 | 28,423 | 4.6 | 4,508 | 14.0 |

| 9 | 7,009 | 4.8 | 1,732 | 10.0 |

| 10 | 12,029 | 5.2 | 3,005 | 5.9 |

| 11 | 16,264 | 5.7 | 4,795 | 9.9 |

| 12 | 4,229 | 6.2 | 937 | 7.3 |

| 13 | 8,964 | 5.2 | 2,039 | 7.8 |

| 14 | 5,459 | 4.8 | 1,161 | 8.5 |

| 15 | 5,637 | 4.9 | 1,436 | 7.3 |

| 16 | 19,848 | 4.9 | 5,671 | 12.0 |

| 17 | 7,878 | 5.7 | 1,994 | 10.4 |

| 18 | 25,012 | 4.5 | 4,842 | 6.6 |

| 19 | 24,283 | 6.5 | 6,375 | 10.4 |

| 20 | 10,870 | 4.9 | 2,509 | 7.3 |

| 21 | 14,895 | 6.2 | 4,366 | 12.1 |

| 22 | 14,402 | 4.6 | 5,582 | 10.3 |

| 23 | 24,271 | 7.1 | 2,872 | 5.6 |

| 24 | 18,038 | 8.2 | 4,295 | 14.9 |

| 25 | 11,857 | 6.4 | 1,694 | 10.3 |

| 26 | 20,111 | 7.5 | 2,407 | 11.5 |

| 27 | 22,196 | 4.0 | 7,378 | 10.8 |

| 28 | 15,968 | 14.1 | 3,910 | 24.6 |

| 29 | 9,917 | 5.1 | 2,482 | 17.3 |

| 30 | 13,254 | 4.3 | 2,827 | 11.7 |

PM intensity values are in arbitrary units.

FIG. 2.

Diagnostic microarray results for three clinical E. coli isolates. (A) Partial microarray layout (position 83); (B to D) microarray images of E. coli isolates 1, 5, and 8, respectively; (E to G) quantitative fluorescent signal intensity analysis for E. coli isolates 1, 5, and 8, respectively.

Genotype analysis.

An overview of the genotypes of all 30 clinical isolates determined with the diagnostic DNA microarray is shown in Table 4. The phenotypes of the isolates were determined by using ciprofloxacin alone or by using ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin (data not shown). Besides one quinolone-sensitive E. coli strain, we identified altogether 29 quinolone-resistant E. coli strains. The quinolone-sensitive isolate had no mutation at amino acid positions 83 and 87. It appeared that 27 quinolone-resistant isolates contained the double mutations S83L and D87N. For one quinolone-resistant isolate we found the mutations S83L and D87Y. Only one quinolone-resistant isolate had the single mutation D87G. The isolates could be further classified into two genotypes with respect to their silent mutations at position 85, 91, and 100. Genotype 1 contained GTC at amino acid position 85, CGC at position 91, and TAT at position 100. Genotype 2 had GTT at position 85, CGT at position 91, and TAC at position 100. In this study, three isolates belonged to genotype 1 and 27 isolates, including the sensitive one, belonged to genotype 2.

TABLE 4.

Genotypes of 30 clinical isolates determined by using the diagnostic DNA microarray

| Strain or no. of isolates | Codon(s) (amino acid[s]) at amino acid positiona:

|

Phenotype | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 67b | 81 | 82 | 83 | 84 | 85 | 87 | 89 | 91b | 100b | 102b | 106b | ||

| E. coli K-12 | GCC (Ala) | GGT (Gly) | GAC (Asp) | TCG (Ser) | GCG (Ala) | GTC (Val) | GAC (Asp) | ATC (Ile) | CGC (Arg) | TAT (Tyr) | CTG (Leu) | CAG (Gln) | |

| 1 | TCG (Ser) | GTT | GAC (Asp) | CGT | TAC | Sensitive | |||||||

| 3 | TTG (Leu) | GTC | AAC (Asn) | CGC | TAT | Resistant | |||||||

| 24 | TTG (Leu) | GTT | AAC (Asn) | CGT | TAC | Resistant | |||||||

| 1 | TTG (Leu) | GTT | TAC (Tyr) | CGT | TAC | Resistant | |||||||

| 1 | TCG (Ser) | GTT | GGC (Gly) | CGT | TAC | Resistant | |||||||

Boldface indicates missense mutations; underlining indicates silent mutations.

This position was outside the region covered by the capture probe and therefore was determined by DNA sequencing.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have developed a microarray-based assay for the detection of quinolone resistance-causing mutations in E. coli gyrA at amino acid positions 83 and 87 for clinical diagnostic purposes.

Although the conventionally used disk diffusion or dilution tests are easy to perform and are applicable without additional equipment, they are time-consuming (requiring more than 1 day) and in some cases are not sensitive enough. In contrast, the microarray-based test can give unambiguous information of deeper depth (genotype) in a shorter assay time (6 h). Nevertheless, presently the use of this methods requires well-trained personnel, more steps involving handling of liquids, and expensive equipment such as fluorescently labeled nucleotides and microarray scanners. Concerning the information depth of the microarray analysis, it is important to note that quinolone resistance (gyrA or parC dependent) may be a question of the selection of naturally occurring mutations in the microbial population. E. coli clones carrying these mutations, which may be overlooked by the usual phenotypic tests, can be selected and enriched due to improper quinolone use. Therefore, the early screening of such mutations that are relevant for quinolone resistance could be helpful in complementing conventional plate assays. Additionally, the exact knowledge of the genotype of a clinical sample containing a putative resistant strain obtained by this assay can help to identify the source of infection and/or the background of an emerging resistance phenomenon in a clinical facility (6, 23, 36).

The advantages of the microarray-based assay over other genotyping assays (SSCP [25], RFLP [29] and MAMA [12]) are (i) the designed probes are directed only against the base change that is relevant to resistance, (ii) different E. coli genotypes can be covered, and (iii) the substitution can be identified. A greater depth of information concerning the identity of the exchanged nucleotide, which cannot be obtained by any of the other three methods, can be obtained by method presented here, due to the use of specific capture probes. In case of microbial antibiotic resistance, such information could be very important. The allele-specific hybridization used in this study is easy to perform compared to other microarray platforms, such as single-base primer extension (26), allele-specific amplification (1), and allele-specific oligonucleotide ligation (13), and therefore is more suitable for clinical applications.

The evaluation of clinical isolates in this work was done with a setup which used hybridization under a standard coverslip. This hybridization method may be disadvantageous in terms of signal yield and reproducibility because of the limited mixing of the sample under the coverslip. To circumvent this drawback, we considered a system using active mixture of samples. In preliminary experiments using automated hybridization stations, we found that with the same amount of target DNA we could increase the specific hybridization signal by a factor of three (data not shown). A further possibility for enhancement of the signal was reviewed by Southern et al. (31). By using a spacer at the 5′ end of the probe, the sensitivity may be further increased. The variation in intensities for different target positions observed in this study is a well known fact and can be explained by a dependency of the hybridization behavior of the capture probe on the nucleotide context of the addressed target sequence (32). The overall intensities corresponding to capture probes designed for position 83 were higher than those for probes directed to position 87. The universal probes for both amino acid positions, which were intended to replace the specific probes in future applications, showed noticeably lower signals than the specific capture probes. This observation can be linked to the lower stability of the DNA duplexes containing inosine compared to those of the standard DNA bases (A:T and G:C) (19). The use of specific probe sets will be preferred in the future, especially as additional information about the E. coli genotype can be extracted for epidemiological studies.

All of the E. coli isolates investigated could be identified correctly regarding the mutations at positions 83 and 87 by using designed probes. All isolates except one had a uniform missense mutation, S83L, which is in accordance with the literature data (5). The further missense mutation at position 87 was either D87N (n = 27) or D87Y (n = 1). The quinolone-resistant isolate without a mutation at position 83 had a D87G mutation, which is also reported for this position, but only in combination with a mutation at position 83 (7). It was speculated that the quinolone resistance of E. coli is developed by stepwise mutation of the gyrA gene followed by the parC gene (14, 15). According to reports to date, the first mutation step on the A subunit of the DNA gyrase takes place at amino acid position 83. The mutation at position 87 without a change at position 83, which was observed in this study, was rarely reported (25). Theoretically, these 29 isolates could contain additional missense mutations in gyrA or other genes, such as parC, because they are not covered by the array described in this publication. However, the two missense mutations in amino acid positions 83 and 87 alone are enough to cause quinolone resistance. From a clinical viewpoint, special attention should be paid to the treatment of E. coli with missense mutations at these two positions because they are the starting point for further missense mutations (for example, in parC) which cause increased quinolone MICs (3, 11, 18, 24). In the future, new capture probes will be designed and added to the microarray as soon as new resistance-causing mutations are discovered in order to broaden the spectrum of the diagnostic microarray.

Conclusion.

The application of the microarray-based single-base-mutation identification assay for resistance detection in clinical diagnostics has been demonstrated with 30 clinical E. coli isolates. Our data show that this kind of assay can be a suitable screening method for identifying prevalent gyrA mutations in clinical isolates of E. coli. Furthermore, such an assay could be used for monitoring of resistance occurrence for long-term antibiotic treatment in medical practices, as well as for the investigation of resistance mechanisms in basic research. The ability to distinguish among different E. coli genotypes including silent mutations also makes it suitable for epidemiological studies. Combined with capture probes designed for other antibiotic resistances, such as beta-lactam resistance and aminoglycoside resistance, the assay could be extended for the detection of multiresistant pathogenic microorganisms in human health care.

Acknowledgments

This project is funded within the GenoMik research initiative by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmadian, A., B. Gharizadeh, D. O'Meara, J. Odeberg, and J. Lundeberg. 2001. Genotyping by apyrase-mediated allele-specific extension. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aoyama, H., K. Sato, T. Kato, K. Hirai, and S. Mitsuhashi. 1987. Norfloxacin resistance in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 31:1640-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bagel, S., V. Hullen, B. Wiedemann, and P. Heisig. 1999. Impact of gyrA and parC mutations on quinolone resistance, doubling time, and supercoiling degree of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 43:868-875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booth, S. A., M. A. Drebot, I. E. Martin, and L. K. Ng. 2003. Design of oligonucleotide arrays to detect point mutations: molecular typing of antibiotic resistant strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and hantavirus infected deer mice. Mol. Cell. Probes 17:77-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cambau, E., and L. Gutmann. 1993. Mechanisms of resistance to quinolones. Drugs 45(Suppl. 3):15-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, J. Y., L. K. Siu, Y. H. Chen, P. L. Lu, M. Ho, and C. F. Peng. 2001. Molecular epidemiology and mutations at gyrA and parC genes of ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from a Taiwan medical center. Microb. Drug Resist. 7:47-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conrad, S., M. Oethinger, K. Kaifel, G. Klotz, R. Marre, and W. V. Kern. 1996. gyrA mutations in high-level fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 38:443-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crumplin, G. C. 1990. Mechanisms of resistance to the 4-quinolone antibacterial agents. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 26(Suppl. F):131-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cullen, M. E., A. W. Wyke, R. Kuroda, and L. M. Fisher. 1989. Cloning and characterization of a DNA gyrase A gene from Escherichia coli that confers clinical resistance to 4-quinolones. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 33:886-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denis, A., and N. J. Moreau. 1993. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance in clinical isolates: accumulation of sparfloxacin and of fluoroquinolones of various hydrophobicity, and analysis of membrane composition. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 32:379-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Everett, M. J., Y. F. Jin, V. Ricci, and L. J. Piddock. 1996. Contributions of individual mechanisms to fluoroquinolone resistance in 36 Escherichia coli strains isolated from humans and animals. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:2380-2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher, L. M., J. M. Lawrence, I. C. Josty, R. Hopewell, E. E. Margerrison, and M. E. Cullen. 1989. Ciprofloxacin and the fluoroquinolones. New concepts on the mechanism of action and resistance. Am. J. Med. 87:2S-8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunderson, K. L., X. H. C. Huang, M. S. Morris, R. J. Lipshutz, D. J. Lockhart, and M. S. Chee. 1998. Mutation detection by ligation to complete n-mer DNA arrays. Genome Res. 8:1142-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heisig, P. 1996. Genetic evidence for a role of parC mutations in development of high-level fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:879-885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heisig, P., and R. Tschorny. 1994. Characterization of fluoroquinolone-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli selected in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1284-1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hooper, D. C., J. S. Wolfson, E. Y. Ng, and M. N. Swartz. 1987. Mechanisms of action of and resistance to ciprofloxacin. Am. J. Med. 82:12-20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karlin, S., and S. F. Altschul. 1990. Methods for assessing the statistical significance of molecular sequence features by using general scoring schemes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:2264-2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khodursky, A. B., E. L. Zechiedrich, and N. R. Cozzarelli. 1995. Topoisomerase IV is a target of quinolones in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11801-11805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin, F. H., M. M. Castro, F. Aboulela, and I. Tinoco. 1985. Base-pairing involving deoxyinosine—implications for probe design. Nucleic Acids Res. 13:8927-8938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mikhailovich, V., S. Lapa, D. Gryadunov, A. Sobolev, B. Strizhkov, N. Chernyh, O. Skotnikova, O. Irtuganova, A. Moroz, V. Litvinov, M. Vladimirskii, M. Perelman, L. Chernousova, V. Erokhin, A. Zasedatelev, and A. Mirzabekov. 2001. Identification of rifampin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains by hybridization, PCR, and ligase detection reaction on oligonucleotide microchips. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2531-2540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mikhailovich, V. M., S. A. Lapa, D. A. Gryadunov, B. N. Strizhkov, A. Y. Sobolev, O. I. Skotnikova, O. A. Irtuganova, A. M. Moroz, V. I. Litvinov, L. K. Shipina, M. A. Vladimirskii, L. N. Chernousova, V. V. Erokhin, and A. D. Mirzabekov. 2001. Detection of rifampicin-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains by hybridization and polymerase chain reaction on a specialized TB-microchip. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 131:94-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moniot-Ville, N., J. Guibert, N. Moreau, J. F. Acar, E. Collatz, and L. Gutmann. 1991. Mechanisms of quinolone resistance in a clinical isolate of Escherichia coli highly resistant to fluoroquinolones but susceptible to nalidixic acid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35:519-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ng, L. K., P. Sawatzky, I. E. Martin, and S. Booth. 2002. Characterization of ciprofloxacin resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates in Canada. Sex. Transm. Dis. 29:780-788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oethinger, M., W. V. Kern, A. S. Jellen-Ritter, L. M. McMurry, and S. B. Levy. 2000. Ineffectiveness of topoisomerase mutations in mediating clinically significant fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli in the absence of the AcrAB efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:10-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ouabdesselam, S., D. C. Hooper, J. Tankovic, and C. J. Soussy. 1995. Detection of gyrA and gyrB mutations in quinolone-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli by single-strand conformational polymorphism analysis and determination of levels of resistance conferred by two different single gyrA mutations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 39:1667-1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pastinen, T., A. Kurg, A. Metspalu, L. Peltonen, and A. C. Syvanen. 1997. Minisequencing: a specific tool for DNA analysis and diagnostics on oligonucleotide arrays. Genome Res. 7:606-614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Piddock, L. J. 1999. Mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance: an update 1994-1998. Drugs 58(Suppl. 2):11-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Power, E. G., J. L. Munoz Bellido, and I. Phillips. 1992. Detection of ciprofloxacin resistance in gram-negative bacteria due to alterations in gyrA. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 29:9-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qiang, Y. Z., T. Qin, W. Fu, W. P. Cheng, Y. S. Li, and G. Yi. 2002. Use of a rapid mismatch PCR method to detect gyrA and parC mutations in ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:549-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith, J. T. 1986. The mode of action of 4-quinolones and possible mechanisms of resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 18(Suppl. D):21-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Southern, E., K. Mir, and M. Shchepinov. 1999. Molecular interactions on microarrays. Nat. Genet. 21:5-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Southern, E. M., S. C. Casegreen, J. K. Elder, M. Johnson, K. U. Mir, L. Wang, and J. C. Williams. 1994. Arrays of complementary oligonucleotides for analyzing the hybridization behavior of nucleic-acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:1368-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Troesch, A., H. Nguyen, C. G. Miyada, S. Desvarenne, T. R. Gingeras, P. M. Kaplan, P. Cros, and C. Mabilat. 1999. Mycobacterium species identification and rifampin resistance testing with high-density DNA probe arrays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:49-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, D. G., J. B. Fan, C. J. Siao, A. Berno, P. Young, R. Sapolsky, G. Ghandour, N. Perkins, E. Winchester, J. Spencer, L. Kruglyak, L. Stein, L. Hsie, T. Topaloglou, E. Hubbell, E. Robinson, M. Mittmann, M. S. Morris, N. P. Shen, D. Kilburn, J. Rioux, C. Nusbaum, S. Rozen, T. J. Hudson, R. Lipshutz, M. Chee, and E. S. Lander. 1998. Large-scale identification, mapping, and genotyping of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the human genome. Science 280:1077-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson, D. L., S. R. Abner, T. C. Newman, L. S. Mansfield, and J. E. Linz. 2000. Identification of ciprofloxacin-resistant Campylobacter jejuni by use of a fluorogenic PCR assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:3971-3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yoo, J. H., D. H. Huh, J. H. Choi, W. S. Shin, M. W. Kang, C. C. Kim, and D. J. Kim. 1997. Molecular epidemiological analysis of quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli causing bacteremia in neutropenic patients with leukemia in Korea. Clin. Infect. Dis. 25:1385-1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshida, H., M. Bogaki, M. Nakamura, and S. Nakamura. 1990. Quinolone resistance-determining region in the DNA gyrase gyrA gene of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 34:1271-1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]