Abstract

One hundred seventy-nine Streptococcus pyogenes isolates recovered from scarlet fever patients from 1996 to 1999 in central Taiwan were characterized by emm, Vir, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) typing methods. The protocols for Vir and PFGE typing were standardized. A database of the DNA fingerprints for the isolates was established. Nine emm or emm-like genes, 19 Vir patterns, and 26 SmaI PFGE patterns were detected among the isolates. Among the three typing methods, PFGE was the most discriminatory. However, it could not completely replace Vir typing because some isolates with identical PFGE patterns could be further differentiated into several Vir patterns. The prevalent emm types were emm4 (n = 81 isolates [45%]), emm12 (n = 64 [36%]), emm1 (n = 14 [8%]), and emm22 (n = 13 [7%]). Some emm type isolates could be further differentiated into several emm-Vir-PFGE genotypes; however, only one genotype in each emm group was usually predominant. DNA from nine isolates was resistant to SmaI digestion. Further PFGE analysis with SgrAI showed that the SmaI digestion-resistant strains could be derived from indigenous strains by horizontal transfer of exogenous genetic material. The emergence of the new strains could have resulted in an increase in scarlet fever cases in central Taiwan since 2000. The emm sequences, Vir, and PFGE pattern database will serve as a basis for information for the long-term evolutionary study of local S. pyogenes strains.

Streptococcus pyogenes causes a variety of human diseases ranging from relatively mild skin infections to severe invasive diseases, such as acute rheumatic fever, glomerulonephritis, puerperal sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, meningitis, and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (9, 29). Among the diseases caused by this pathogen, scarlet fever, characterized by a strawberry tongue, skin rash, and sore throat, is most prevalent in schoolchildren aged 4 to 7 years. In Taiwan, scarlet fever is a notifiable disease, with 150 to 230 confirmed cases per year from 1996 to 1999. Since only 9% of the medical centers, regional hospitals, and district hospitals in central Taiwan had ever reported cases to the health authorities from 1996 to 1999, the number of scarlet fever cases should be severely underreported. Scarlet fever outbreaks are not uncommon at day-care centers, kindergartens, and elementary schools (5, 16). However, the molecular epidemiology of this disease has not been well studied in Taiwan.

Analysis of the clonal relationships between clinical isolates from patients by various typing methods is a practical approach to elucidation of the epidemiology of a disease. To date, a number of phenotyping and genotyping methods have been described for S. pyogenes (1, 3, 10, 13, 18-20, 22, 26, 27, 30, 33). Among these methods, M serotyping has been taken as the “gold standard” for the characterization of S. pyogenes strains, in light of its importance to streptococcal virulence. However, application of M serotyping is restricted due to the lack of a comprehensive set of antisera in most laboratories and the high proportion of nontypeable isolates (21). In recent years, M serotyping has been replaced by sequencing of the 5′ emm-coding region. Because the emm sequence can be used reliably to predict the M serotype and the sequences can be compared online, this method has been used worldwide as an epidemiologic tool to characterize S. pyogenes isolates recovered from patients with various diseases. This method has helped to identify many new emm and emm-like genes (12, 32). Vir typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) are the other two powerful subtyping methods for epidemiologic investigations of S. pyogenes infections. Vir typing, based on restriction length fragment polymorphisms of the 5- to 7-kb Vir regulon region of S. pyogenes, has been shown to be highly discriminatory and applicable to all S. pyogenes strains and provides a good correlation between the Vir type and the M serotype (13, 14). PFGE is based on restriction length fragment polymorphisms of the whole microbial genome and allows detection of variations among strains. Despite its usefulness, the results from Vir typing and PFGE generated between laboratories are not comparable unless a standardized protocol is followed.

In the study described here, 179 S. pyogenes isolates were characterized by the emm, Vir, and PFGE typing methods to investigate the epidemiologic aspects of scarlet fever in Taiwan. The protocols for the Vir and PFGE methods were standardized, and the typing patterns were analyzed with computer software that permits them to be compared online.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The S. pyogenes isolates were recovered from scarlet fever patients in hospitals in central Taiwan from 1996 to 1999. Isolates were sent to the Central Branch Office of the Center for Disease Control of Taiwan with reporting forms that contained information for each patient, including the patient's name, sex, birthday, residence, day of onset of scarlet fever, and symptoms. Salmonella enterica serovar Braenderup H9812 was obtained from Bala Swaminathan of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Ga. The bacterial isolates were stored in 15% glycerol at −70°C until use.

Prediction of suitable restriction enzymes for PFGE analysis of S. pyogenes.

The Restriction Digest Tool provided on The Institute for Genome Research website (http://www.tigr.org/) was used to search for the restriction enzyme sites on the genome sequences of S. pyogenes strains MGAS315, MGAS8232, SF370, and SSI-1 to generate restriction fragment length profiles. Each of the four genomic sequences contained 8 to 57 restriction sites for the restriction enzymes, and the genomic sequences were further evaluated for their fragment size distributions. In the standard PFGE protocol, XbaI-digested genomic DNA fragments of S. enterica serovar Braenderup H9812 were used as reference size markers in PFGE gels. Therefore, only those fragments with sizes ranging from 21 to 1,135 kb were counted as analyzable by the pattern analysis software.

PFGE analysis.

The standard PFGE protocol for S. pyogenes was developed on the basis of PulseNet's Listeria monocytogenes PFGE protocol, with minor modifications (15). Briefly, the S. pyogenes isolates were grown on blood agar plates incubated in 5% CO2 at 35°C for 16 to 24 h. The standard PFGE protocol for L. monocytogenes was followed to prepare the bacterial cell suspension, determine the bacterial concentration, make agarose plugs, lyse the bacterial cells, and wash the agarose plugs. Plug slices (width, 2 mm) were digested with 10 U of SmaI or 20 U of SgrAI. The DNA fragments were then separated in 1% Seakem Gold agarose gels (FMC BioProducts) at 14°C with a Bio-Rad CHEF Mapper apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE; pH 8) at a 120° fixed angle, at a fixed voltage (6 V/cm), and with pulse time intervals from 4 to 40 s for 20 h. The XbaI-digested genomic DNA fragments of S. enterica ser. Braenderup H9812 were used as reference size markers. The gel was stained with 1 mg of ethidium bromide per liter for 30 min and destained for 60 to 90 min with water that had been subjected to reverse osmosis, and the water was changed every 20 to 30 min. The gel was exposed on a UV transilluminator, and the image was captured digitally with a gel documentation system (AlphaImager 2000; Alpha Innotech Corporation, San Leandro, Calif.).

emm typing.

The procedure developed by Beall et al. (1) was used to prepare the emm DNA fragments from the S. pyogenes isolates for nucleotide sequence determination. The amplified DNA amplicons and primer 1 were sent to a biotechnology company (Mission Biotech Corp., Taipei, Taiwan) for DNA sequencing. The first 160 bp of each of the 5′ emm sequences was compared with the sequences in the emm database for determination of the degrees of homology(http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/biotech/strep/strepindex.html) to determine emmtypes.

Vir typing.

The standard Vir typing protocol was developed by modifying the procedures described by Gardiner et al. (13). Briefly, S. pyogenes was grown on 5% sheep blood agar and then incubated in 5% CO2 environment at 35°C for 16 to 24 h. A loop of bacterial growth was transferred into an Eppendorf tube containing 200 μl of lysozyme reaction solution (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 2 mM EDTA, 20 μg of lysozyme per ml) and then suspended by vigorously vortexing and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The cells were then lysed by freezing and thawing the cell suspension five times in liquid nitrogen for 2 min and boiling water for 2 min. The lysate was then subjected to DNA extraction with a commercial kit (Blood & Tissue Genomic DNA Extraction Miniprep System; Viogene, Taipei, Taiwan). DNA was finally eluted with 100 μl of TE (Tris-EDTA) buffer and stored at −75°C until use.

The Vir regulon region was amplified with a commercial long PCR kit (TaKaRa Ex Taq; TaKaRa Shuzo Co., Kyoto, Japan). Briefly, a 50-μl PCR mixture containing 2 μl of the genomic DNA solution, 0.4 μM primers VUF and SBR (13), 250 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1× Ex Taq buffer, and 1.25 U of TaKaRa Ex Taq was subjected to 1 cycle at 94°C for 2 min and then 25 cycles at 94°C for 10 s, 60°C for 2 min, and 68°C for 6 min. Five microliters of the PCR product was digested with 5 U of HaeIII at 37°C for 1 h. The DNA fragments were then separated by electrophoresis in a 2% agarose gel in 0.5% TBE buffer at 6 V/cm for 2 h. The 100-bp ladder DNA (GeneTeks BioScience Inc., Taipei, Taiwan) was loaded at five-well intervals and used as a reference size marker. The gel was stained with 1 mg of ethidium bromide per liter for 30 min and destained for 60 min with water that had been subjected to reverse osmosis, and the water was changed every 20 to 30 min. The gel was exposed on a UV transilluminator, and the image was captured digitally with a gel documentation system (AlphaImager 2000, Alpha Innotech Corporation).

Computer analysis.

The digital PFGE pattern and Vir pattern images were analyzed with BioNumerics software (Applied Maths, Kortrijk, Belgium). The computer software provided functions to set up a database of DNA patterns for pattern identification and phylogenetic analysis. With the aid of the computer software, dendrograms derived from the PFGE patterns and the Vir patterns were constructed by use of the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) algorithm, based on Dice similarity coefficients.

RESULTS

emm typing.

A total of nine emm sequence types were identified among the 179 isolates. emm4, emm12, emm1, and emm22 were the prevalent types; in total 81 (45%), 64 (36%), 14 (8%), and 13 (7%) isolates, respectively, were of these types (Table 1). The yearly percentages of emm1, emm12, and emm22 fluctuated, but that of emm4 decreased over the years. Each of the rare emm types (emm6, emm33, emm74, emm113, and st11014) was detected in only one or two isolates. st11014 (GenBank accession number AF089737) from isolate Sp11014 was a new emm-like type. No emm gene was detected in isolate Sp9414. Further PCR and PFGE studies suggested that the strain could have been derived from an emm4 strain with a DNA deletion in the emm region (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of emm type by year

| Yr | No. (%) of isolates

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| emm1 | emm4 | emm12 | emm22 | Others | Total | |

| 1996 | 9 (90) | 1 (10) | 10 (100) | |||

| 1997 | 1 (2) | 29 (52) | 22 (39) | 2 (4) | 2 (4)a | 56 (100) |

| 1998 | 9 (14) | 27 (42) | 17 (26) | 9 (14) | 3 (5)b | 65 (100) |

| 1999 | 4 (8) | 16 (33) | 24 (50) | 2 (4) | 2 (4)c | 48 (100) |

| Total | 14 (8) | 81 (45) | 64 (36) | 13 (7) | 7 (4) | 179 (100) |

emm113 and no emm gene detected.

emm33, emm74, and st11014.

emm6.

Vir typing.

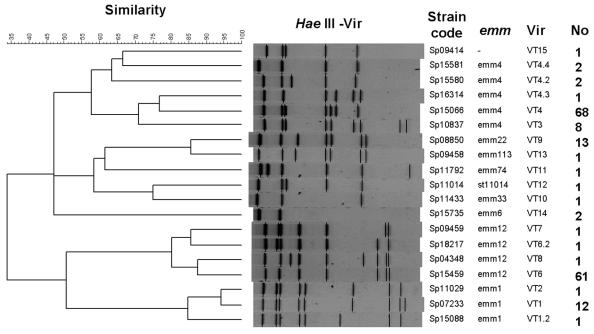

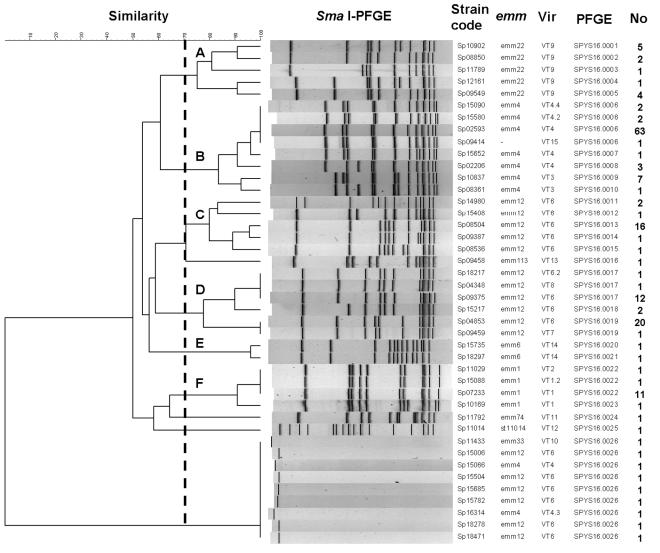

All of the isolates were successfully analyzed by the standard Vir typing protocol. As shown in Fig. 1, most of the HaeIII restriction fragments were located within the range of the reference size markers (0.1 to 3 kb). As a result, the Vir patterns from different gels could be analyzed with the BioNumerics software, by which 19 Vir types were identified among the isolates tested. To compare the clonal relationships between the isolates by use of the Vir patterns, a dendrogram was generated with the UPGMA algorithm by using the Dice coefficients (Fig. 2). The dendrogram, combined with the emm type information, revealed that isolates with identical emm types were located in a closer cluster. Isolates with different emm types had different Vir types, while isolates with identical emm types could be of different Vir types. Isolates of types emm4, emm12, and emm1 were further differentiated into five, four, and three Vir types, respectively. Although several Vir types could be derived from a common emm type, a predominant Vir type usually existed. Vir type 4 (VT4) of emm4, VT6 of emm12, and VT1 of emm1 accounted for 84% (68 of 81 isolates), 95% (61of 64 isolates), and 86% (12 of 14 isolates) of the isolates in the groups, respectively.

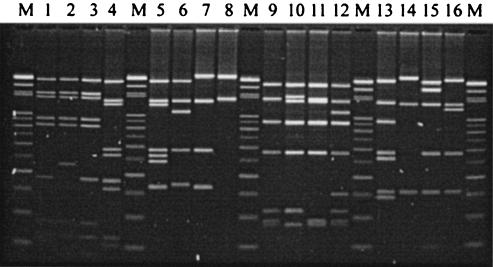

FIG. 1.

Representative Vir patterns of genomes of 16 S. pyogenes isolates digested with HaeIII. Vir typing was performed by the standard protocol described in Materials and Methods. Lanes M, 100-bp ladders used as reference size markers; lanes 1 to 16, S. pyogenes isolates Sp07233 (VT1, emm1), Sp15088 (VT1.2, emm1), Sp11029 (VT2, emm1), Sp10837 (VT3, emm4), Sp15066 (VT4, emm4), Sp15580 (VT4.2, emm4), Sp15581 (VT4.4, emm4), Sp15735 (VT14, emm6), Sp15459 (VT6, emm12), Sp18217 (VT6.2, emm12), Sp09459 (VT7, emm12), Sp04348 (VT8, emm12), Sp08850 (VT9, emm22), Sp11433 (VT10, emm33), Sp11792 (VT11, emm74), and Sp11014 (VT12, st11014), respectively.

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram and Vir patterns of S. pyogenes isolates and the association with emm types and the number of isolates belonging to the genotype. The dendrogram was constructed with BioNumerics software, with 3% optimization and 0.85% position tolerance, by using the UPGMA algorithm with Dice similarity coefficients.

Restriction enzymes for S. pyogenes PFGE analysis.

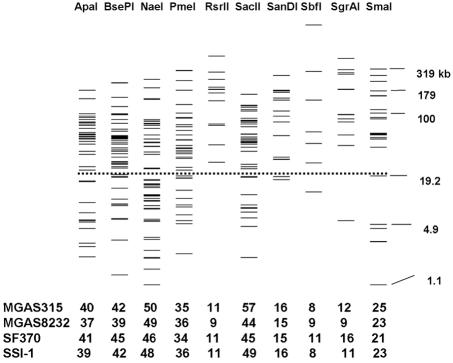

Ten restriction enzymes with 8 to 57 restriction sites on the genomes of each of S. pyogenes strains SSI-1, SF370, MGAS315, and MGAS823 were found by using the Restriction Digestion Tool provided on The Institute for Genome Research website. The restriction profiles of the 10 restriction enzymes for strain MGAS315 are shown in Fig. 3. By the PFGE protocol, XbaI-digested genomic DNA of S. enterica serovar Braenderup H9812 was used as the reference size marker. Only fragments with sizes between 20.5 and 1,135 kb were counted as effective bands in the analysis with the BioNumerics fingerprint analysis software. As predicted, most fragments produced by digestion with RsrII, SanDI, SbfI, SgrAI, and SmaI were larger than 21 kb and could be clearly resolved on the gel under the run conditions set for this study (Fig. 3). ApaI, BsePI, NaeI, PmeI, and SacII generated many smaller fragments; however, many of them were smaller than 21 kb and could not be clearly separated in the gel. Therefore, SgrAI and SmaI were selected for PFGE analysis of S. pyogenes, in view of the lower prices for the enzymes and the more separable fragments produced.

FIG. 3.

Restriction profiles of 10 rarely cutting restriction enzymes for S. pyogenes strain MGAS315 and the number of restriction sites in the genomes of strains MGAS315, MGAS8232, SF370, and SSI-1. The prediction was done with the whole genome sequences of the indicated strains by use of the Restriction Digest Tool provided on The Institute for Genome Research website (http://www.tigr.org/). Fragments above the dashed line (>21 kb) are effective for analysis with the reference size markers, XbaI-digested DNA of S. enterica serovar Braenderup strain H9812. The numbers at the bottom indicate the numbers of restriction sites on the genome of the indicated strains.

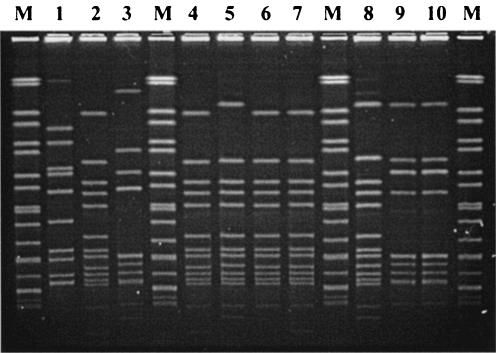

PFGE typing.

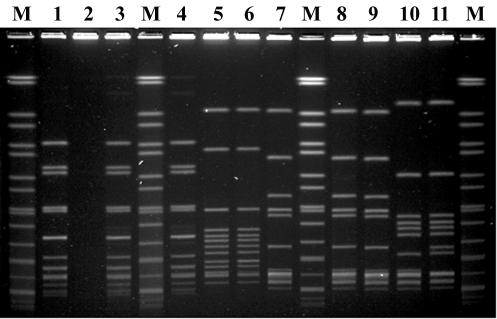

The modified PFGE protocol for L. monocytogenes worked successfully for S. pyogenes. Most of the SmaI restriction fragments could be clearly separated in the agarose gels, and most of the fragments were located within the range of sizes of the reference size markers (Fig. 4). A total of 26 PFGE patterns were identified among the 179 isolates. DNA from 170 isolates could be digested with SmaI, but 9 isolates were resistant to SmaI digestion. To analyze the clonal relationships among the isolates by use of the SmaI PFGE patterns, a dendrogram was generated by use of the UPGMA algorithm with Dice coefficients (Fig. 5). Six distinct clusters (clusters A, B, C, D, E, and F) with similarity coefficients greater than 70% were designated. Isolates in each cluster harbored identical emm types. The dendrogram combined with the emm and Vir type data showed that isolates with identical emm types had a closer relationship than those with different emm types. However, emm12 isolates were located in two distinct clusters (clusters C and D), suggesting that emm12 isolates could have been derived from two origins or from a clone that diverged into two distinct groups at an earlier time. In each emm cluster with several Vir-PFGE types, a predominant Vir-PFGE type usually existed. For example, emm4-VT4-SPYS16.0006 in cluster B, emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0013 in cluster C, emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0019 in cluster D, and emm1-VT1-SPYS16.0022 in cluster F accounted for 79% (63 of 80 isolates), 76% (16 of 21), 54% (20 of 37), and 79% (11 of 14) emm cluster isolates, respectively. These studies indicated that PFGE typing has a higher discriminatory power than Vir typing; however, it cannot completely replace Vir typing. Some isolates with identical PFGE patterns (SPYS16.0006, SPYS16.0017, SPYS16.0019, and SPYS16.0022) could be further discriminated by Vir typing.

FIG. 4.

Representative PFGE patterns of 11 S. pyogenes isolates obtained by the standard PFGE protocol with SmaI digestion described in Materials and Methods. Lanes M, chromosomal DNA of S. enterica serovar Braenderup H9812 digested with XbaI as reference size markers (size range, 20.5 to 1,135 kb). Lane 1, S. pyogenes isolate Sp15601 (SPYS16.0006, emm4); lane 2, Sp16314 (SPYS16.0026, emm4); lane 3, Sp15090 (SPYS16.0006, emm4); lane 4, Sp15581 (SPYS16.0006, emm4); lane 5, Sp15735 (SPYS16.0020, emm6); lane 6, Sp18297 (SPYS16.0021, emm6); lane 7, Sp04853 (SPYS16.0019, emm12); lane 8, Sp05265 (SPYS16.0019, emm12); lane 9, Sp7286 (SPYS16.0019, emm12); lane 10, Sp08504 (SPYS16.0013, emm12); lane 11, Sp8536 (SPYS16.0015, emm12). The chromosomal DNA of strain Sp16314 was resistant to SmaI digestion.

FIG. 5.

Dendrogram and PFGE patterns of SmaI-digested chromosomal DNA of S. pyogenes isolates and association with emm types, Vir patterns, and the number of isolates belonging to these genotypes. The dendrogram was constructed with BioNumerics software, with 4% optimization and 1% position tolerance, by using the UPGMA algorithm and Dice similarity coefficients. The clusters (clusters A, B, C, D, E, and F) contained isolates with similarity coefficients greater than 70% (indicated by the dashed line).

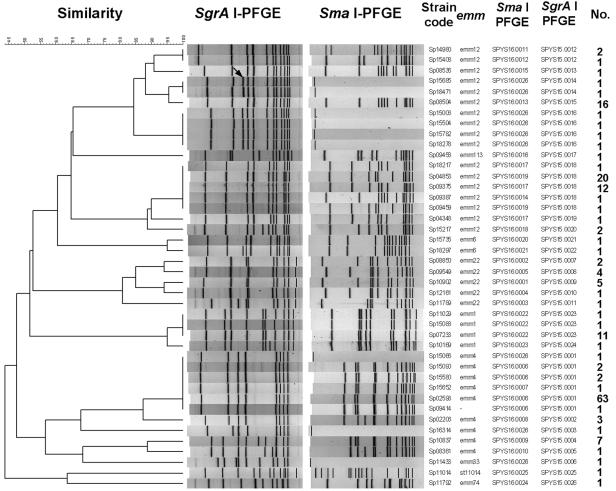

To investigate the clonal relationships and the evolutionary origins of the nine isolates that could not be digested with SmaI, the 42 isolates listed in Fig. 5 were analyzed by PFGE with SgrAI. All of the isolates were typeable with the enzyme, and 8 to 12 restriction fragments with sizes in the range of those of the reference size markers were observed (Fig. 6). A dendrogram generated from the SgrAI PFGE patterns showed clusters similar to those generated from the SmaI PFGE patterns (Fig. 7). From the comparison of the SmaI PFGE and SgrAI PFGE patterns, a close relationship was found between the six emm12 isolates that could not be digested with SmaI and the SYS16.0013 strain and between an emm4 isolate that could not be digested with SmaI and the SYS16.0006 and SYS16.0007 strains (Fig. 7). In the dendrogram, an extra 220-kb fragment was observed for the SmaI-indigestible emm12 isolates but not for the SYS16.0013 strain (Sp08504), suggesting that the SmaI-indigestible isolates could have originated from an indigenous strain by the acquisition of exogenous genetic material.

FIG. 6.

Representative PFGE patterns of genomes of 10 S. pyogenes isolates digested with SgrAI. The chromosomal DNA of the S. pyogenes isolates was resistant to SmaI digestion. Lanes M, chromosomal DNA of S. enterica serovar Braenderup H9812 digested with XbaI as reference size markers (size range, 20.5 to 1,135 kb); lane 1, S. pyogenes isolate Sp11433 (SPYS15.0006, emm33); lane 2, Sp15006 (SPYS15.0016, emm12); lane 3, Sp15066 (SPYS15.0001, emm4); lane 4, Sp15504 (SPYS15.0016, emm12); lane 5, Sp15685 (SPYS15.0014, emm12); lane 6, Sp15782 (SPYS15.0016, emm12); lane 7, Sp18278 (SPYS15.0016, emm12); lane 8, Sp18471 (SPYS15.0014, emm12); lanes 9 and 10, Sp16314 (SPYS15.0003, emm4).

FIG. 7.

Dendrogram and PFGE patterns of chromosomal DNA of S. pyogenes isolates digested with SgrAI and the association with SmaI PFGE patterns, emm types, and the numbers of isolates belonging to these genotypes. The dendrogram was constructed with BioNumerics software, with 3% optimization and 1% position tolerance, by using the UPGMA algorithm and Dice similarity coefficients. A 220-kb DNA fragment (shown by the arrow) appeared with the six strains (Sp15685, Sp18471, Sp15006, Sp15504, Sp15782, and Sp18278) resistant to digestion with SmaI.

Distribution of genotypes by time.

Thirty-seven emm-Vir-PFGE (SmaI) genotypes were identified (Fig. 5). Of these, 15 emm-Vir-PFGE genotypes were identified in two or more isolates. The temporal distributions of these genotypes fluctuated (Table 2). Five major genotypes (emm1-VT1-SPYS16.0022, emm4-VT4-SPYS16.0006, emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0013, emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0017, and emm22-VT9-SPYS16.0005) haveemerged since 1997 or earlier and lasted until 1999. Of these five major genotypes, the population (percentage) of emm4-VT4-SPYS16.0006 decreased over time, but that of emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0017 increased abruptly in 1999. Three genotypes (emm4-VT3-SPYS16.0009, emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0019, and emm22-VT9-SPYS16.0001) emerged and then disappeared in 1999. Six emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0026 isolates that had genomic DNA that was resistant to SmaI digestion and that emerged in 1999 could have derived from an emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0013 strain. Whether the emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0017 and emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0026 genotypes could become major epidemic genotypes in the area deserves further study. The numbers of isolates of minor genotypes increased from 7 in 1997 and 9 in 1998 to 16 in 1999. Most of the minor genotypes were identified in one or two isolates.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of major emm-Vir-PFGE genotypes by year

| Yr | No. (%) of isolates

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| emm1-VT1-SPYS16.0022 | emm4-VT4-SPYS16.0006 | emm4-VT3-SPYS16.0009 | emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0013 | emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0017 | emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0019 | emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0026 | emm22-VT9-SPYS16.0001 | emm22-VT9-SPYS16.0005 | Othersa | Total | |

| 1996 | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | 10 (100) | ||||||||

| 1997 | 1 (2) | 24 (43) | 4 (7) | 5 (9) | 1 (2) | 13 (23) | 1 (2) | 7 (13) | 56 (100) | ||

| 1998 | 7 (11) | 23 (35) | 3 (5) | 8 (12) | 1 (2) | 7 (11) | 5 (8) | 2 (3) | 9 (14) | 65 (100) | |

| 1999 | 3 (6) | 9 (19) | 3 (6) | 10 (21) | 6 (13) | 1 (2) | 16 (33) | 48 (100) | |||

| Total | 11 (6) | 63 (35) | 7 (4) | 16 (9) | 12 (7) | 20 (11) | 6 (3) | 5 (3) | 4 (2) | 35 (20) | 179 (100) |

Includes 2, 7, 9, and 13 emm-VT-PFGE genotypes, in the years 1996, 1997, 1998, and 1999, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we characterized the emm genes and the restriction profiles of the Vir regulon and chromosomes of 179 isolates recovered from patients in central Taiwan with scarlet fever from 1996 to 1999. The operating procedures for the Vir and PFGE analyses were standardized. Standardization of the analysis procedures for PFGE and Vir typing has made the DNA patterns produced in different gels comparable and helped to set up a database of fingerprints for the S. pyogenes isolates. This fingerprint database can serve as a basis for the long-term epidemiologic study of the S. pyogenes isolates in this area.

The M protein, which is encoded by the emm gene, is an important virulence factor for S. pyogenes (2). It has been reported that strains of certain M serotypes are epidemiologically associated with particular clinical syndromes. For example, both M1 and M3 strains were associated particularly with invasive diseases and fatal infections in Britain from 1980 to 1990 (8) and in the United States from 1995 to 1999 (23). M18 strains were associated with acute rheumatic fever (28). However, in a comparison study with control isolates from patients with noninvasive infections, Johnson et al. (17) indicated that the hypothesis that the increase in invasive infections in the United States during the late 1980s and 1990s was associated with particular M-protein types was not supported by the statistical evidence. Instead, the increase was a result of the increased numbers of strains of those particular M serotypes circulating in the general population at that time. Those investigators suggested that host factors, including individual and population-based immunity, must also be significant in influencing the infection potential. Among the M serotypes, M1, M2, M3, M4, M6, and M22 were detected among the isolates associated with scarlet fever (11, 24, 25, 34). In this study, we showed that the prevalent emm types for the S. pyogenes isolates collected in central Taiwan between 1996 and 1999 were emm4 (45%), emm12 (36%), emm1 (8%), and emm22 (7%). The epidemiologic pattern, however, is inconsistent with that in southern Taiwan, 180 km away. Yan et al. (34) showed that only the emm1 (72.7%), emm4 (26.0%), and emm25 (1.3%) types were found among the isolates recovered in southern Taiwan from 1993 to 2002. The emm1 isolates appeared in all years studied. In contrast, emm4 emerged only from 1995 to 2000, with a peak in 1997. Our data showed that in central Taiwan, emm12 is a major type among the isolates and the incidence rate was increasing in 1999. However, it was not identified in the isolates in southern Taiwan during the same period. Although the number of emm types identified in central and southern Taiwan was limited to a few types, it cannot be concluded that scarlet fever is associated only with those M serotypes. The high prevalence of those serotypes among the isolates causing scarlet fever during this period could result from an increase in the particular M serotypes circulating in the general population in that area.

Usually, only a small number of infected people develop symptoms in a scarlet fever outbreak (24). This also occurs with other invasive streptococcal diseases (6). As a streptococcal epidemic occurs, it is not easy to provide an outbreak alert by identification of only a few sporadic cases. Therefore, a sensitive surveillance system that uses modern molecular subtyping techniques is needed for the early detection of a streptococcal epidemic. PulseNet, a national molecular subtyping network for surveillance of food-borne diseases developed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is a successful example (31). This network has been proven to be effective for the early detection of food-borne disease outbreaks by PFGE analysis of the sporadic cases that occur in different geographical areas as a result of extensive food distribution (4). Molecular subtyping of S. pyogenes isolates by standard PFGE procedures and the development of a database of DNA fingerprints for these isolates will help to identify streptococcal epidemics at the early stages and allow monitoring of the changes in epidemiologic patterns.

PFGE patterns are generated in image form, but these are difficult to compare with those generated from different gels or those generated by different laboratories because the migration of the DNA bands in the gel can be affected by many factors, such as the strength of the agarose, the electrophoretic apparatus, and the electrophoretic conditions. To make PFGE image patterns comparable, the operating procedures that must be standardized include the DNA preparation methods, the restriction enzyme(s), the reference size markers, and the electrophoretic conditions used. In this study, we standardized a PFGE protocol for S. pyogenes by modifying the standard PFGE protocol for L. monocytogenes (15). Our results indicated that the DNA preparation and electrophoretic conditions used for Listeria work well for the S. pyogenes isolates and that the size range of the reference size markers made from S. enterica serovar Braenderup strain H9812 covered most of the DNA fragments generated by SmaI and SgrAI digestion of the genomic DNA. During the development of the PFGE standard protocol for S. pyogenes, the restriction enzymes were not selected from trial-and-error tests. Instead, they were searched for by using computer prediction of the whole genomic sequences of S. pyogenes strains and were chosen in view of enzyme cost and the size range of the reference size markers used. Among the 10 restriction enzymes found in the computer searches, RsrII, SanDI, SmaI, and SgrAI generated good PFGE patterns when the electrophoretic conditions and the reference size markers made from S. enterica serovar Braenderup strain H9812 were used. However, RsrII and SanDI are quite expensive and are not a good choice for use in routine PFGE analysis. Another five restriction enzymes (ApaI, BsePI, NaeI, PmeI, and SacII) generated many small fragments. They could be good for PFGE analysis under electrophoretic conditions that favor the separation of small fragments and in which reference size markers with a size range covering most of the fragments are used. Since many microbial genomic sequences have been deciphered, the restriction enzymes suitable for PFGE analysis of these microbes can be predicted by computer programs, which can save on the tremendous amounts of time and money usually spent on trial-and-error tests.

Our data showed that PFGE exhibited a higher discriminatory power than Vir typing for the local S. pyogenes isolates tested. However, the data showed that some isolates with identical PFGE patterns could be further discriminated by Vir typing (Fig. 5). Therefore, PFGE cannot completely replace Vir typing, which detects variations in the Vir regulon, a small region of 5 to 7 kb. Size variations in the small region cannot usually be detected by PFGE analysis. The dendrograms generated from the PFGE and Vir patterns showed that isolates with identical emm types are usually located in a distinct cluster (Fig. 2 and 5), implicating a common evolutionary origin for the emm isolates. The dendrograms generated from the SmaI PFGE patterns (Fig. 5) showed that emm12 isolates are located in two distinct clusters, indicating that the emm12 isolates could have been derived from two evolutionary origins or from a common origin that diverged into two groups at an earlier time. Compared to PFGE and Vir typing, emm typing exhibited much less discriminatory power. However, it was a good molecular marker that could be used to infer the evolutionary relationships among the local S. pyogenes isolates analyzed by PFGE and Vir typing.

The clustering analysis based on the SmaI PFGE patterns showed six distinct clusters. Each of the clusters contained isolates harboring the same emm type (Fig. 5). The different Vir-PFGE genotypes in a cluster could be derived from a common emm clone. A major emm-Vir-PFGE genotype usually existed in each cluster. For example, genotypes emm4-VT4-SPYS16.0006 and emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0013 were the major emm-Vir-PFGE genotypes in clusters B and C, respectively (Fig. 5). The clone of the major genotype usually emerged over several years and was distributed over a wide area. However, some emerged and then soon disappeared. For instance, emm1-VT1-SPYS16.0022 of cluster F, emm4-VT4-SPYS16.0006 of cluster B, emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0013 of cluster C, and emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0017 of cluster D were detected from 1997 to 1999; but emm4-VT3-SPYS16.0009 of cluster B, emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0019 of cluster D, and emm22-VT9-SPYS16.0001 of cluster A emerged over a short period of time (Table 2). A strain of emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0019 caused an outbreak in a kindergarten in December 1998 but did not spread into the community (5). Whether a major genotype can maintain its predominance or can be replaced by a genotype derived from it deserves to be watched. The database of fingerprints for the S. pyogenes isolates set up in this study will provide a basis of information for the long-term surveillance of the evolution of the genotypes.

PFGE identified nine isolates with DNA resistant to SmaI digestion. These isolates have emerged since 1998, and the number increased in 1999. Because DNA resistant to SmaI digestion was detected in isolates with different emm and Vir types, it is highly probable that this characteristic is carried on a mobile genetic element, which was supported by comparison of the PFGE patterns of the resistant and susceptible strains. By comparison of the SgrAI PFGE patterns, a 220-kb fragment was found in the SmaI digestion-resistant isolates but not in the SmaI digestion-susceptible emm12 isolates (Fig. 7), suggesting that this DNA had been inserted into an indigenous emm12-VT6-SPYS16.0013 clone that had been circulating in the area for a long time. However, there were no differences in the SgrAI PFGE patterns of the SmaI digestion-resistant and -susceptible emm4 isolates (Fig. 7). The genetic material was undetectable in the isolates by PFGE analysis. The SmaI digestion resistance phenomenon in an S. pyogenes strain was reported in 1997 by Cocuzza et al. (7). However, the genetic material responsible for this characteristic has not been studied yet. In addition to the modification on the SmaI site, whether the genetic material also carries a virulence factor(s) that leads to a dramatic increase in scarlet fever cases caused by the digestion-resistant strains in 2000 must be investigated further.

We have observed an increasing number of scarlet fever cases since 2000. In central Taiwan, the number of cases in 2002 was four times greater than that in 1999. This increase could result from the emergence of a virulent strain, a higher reporting rate, restrictions on antibiotic usage since 2000, or other environmental factors. The emm sequence, PFGE, and Vir fingerprint database for the S. pyogenes isolates made in this study will serve as a basis for information for epidemiologic studies of this disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant DOH91-DC-2010 from the Center for Disease Control, DOH, of Taiwan.

We thank Bala Swaminathan and Lewis Graves of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for providing PFGE and BioNumerics training and Bernard Beall for identifying the new emm-like gene. We also thank our colleagues Shu-Ying Li and Hwa-Jen Teng for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beall, B., R. Facklam, and T. Thompson. 1996. Sequencing emm-specific PCR products for routine and accurate typing of group A streptococci. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:953-958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisno, A. L., M. O. Brito, and C. M. Collins. 2003. Molecular basis of group A streptococcal virulence. Lancet Infect. Dis. 3:191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruneau, S., H. de Montclos, E. Drouet, and G. A. Denoyel. 1994. rRNA gene restriction patterns of Streptococcus pyogenes: epidemiological applications and relation to serotypes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2953-2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2000. Multistate outbreak of listeriosis—United States, 2000. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 49:1129-1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chao, T. Y., H. C. Lu, C. S. Chiou, H. C. Chen, T. M. Pan, and K. T. Chen. 1998. An epidemiological investigation of a scarlet fever outbreak at a kindergarten in Taichung City. Epidemiol. Bull. 14:113-121. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cockerill, F. R., III, K. L. MacDonald, R. L. Thompson, F. Roberson, P. C. Kohner, J. Besser-Wiek, J. M. Manahan, J. M. Musser, P. M. Schlievert, J. Talbot, B. Frankfort, J. M. Steckelberg, W. R. Wilson, and M. T. Osterholm. 1997. An outbreak of invasive group A streptococcal disease associated with high carriage rates of the invasive clone among school-aged children. JAMA 277:38-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cocuzza, C. E., R. Mattina, A. Mazzariol, G. Orefici, R. Rescaldani, A. Primavera, S. Bramati, G. Masera, F. Parizzi, G. Cornaglia, and R. Fontana. 1997. High incidence of erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes in Monza (north Italy) in untreated children with symptoms of acute pharyngo-tonsillitis: an epidemiological and molecular study. Microb. Drug Resist. 3:371-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colman, G., A. Tanna, A. Efstratiou, and E. T. Gaworzewska. 1993. The serotypes of Streptococcus pyogenes present in Britain during 1980-1990 and their association with disease. J. Med. Microbiol. 39:165-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Efstratiou, A. 2000. Group A streptococci in the 1990s. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45(Suppl.):3-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enright, M. C., B. G. Spratt, A. Kalia, J. H. Cross, and D. E. Bessen. 2001. Multilocus sequence typing of Streptococcus pyogenes and the relationships between emm type and clone. Infect. Immun. 69:2416-2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espinosa de los Monteros, L. E., I. M. Bustos, L. V. Flores, and C. Avila-Figueroa. 2001. Outbreak of scarlet fever caused by an erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pyogenes emm22 genotype strain in a day-care center. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 20:807-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Facklam, R. F., D. R. Martin, M. Lovgren, D. R. Johnson, A. Efstratiou, T. A. Thompson, S. Gowan, P. Kriz, G. J. Tyrrell, E. Kaplan, and B. Beall. 2002. Extension of the Lancefield classification for group A streptococci by addition of 22 new M protein gene sequence types from clinical isolates: emm103 to emm124. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:28-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gardiner, D., J. Hartas, B. Currie, J. D. Mathews, D. J. Kemp, and K. S. Sriprakash. 1995. Vir typing: a long-PCR typing method for group A streptococci. PCR Methods Appl. 4:288-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardiner, D. L., and K. S. Sriprakash. 1996. Molecular epidemiology of impetiginous group A streptococcal infections in Aboriginal communities of northern Australia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:1448-1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graves, L. M., and B. Swaminathan. 2001. PulseNet standardized protocol for subtyping Listeria monocytogenes by macrorestriction and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 65:55-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsueh, P. R., L. J. Teng, P. I. Lee, P. C. Yang, L. M. Huang, S. C. Chang, C. Y. Lee, and K. T. Luh. 1997. Outbreak of scarlet fever at a hospital day care centre: analysis of strain relatedness with phenotypic and genotypic characteristics. J. Hosp. Infect. 36:191-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson, D. R., J. T. Wotton, A. Shet, and E. L. Kaplan. 2002. A comparison of group A streptococci from invasive and uncomplicated infections: are virulent clones responsible for serious streptococcal infections? J. Infect. Dis. 185:1586-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufhold, A., A. Podbielski, G. Baumgarten, M. Blokpoel, J. Top, and L. Schouls. 1994. Rapid typing of group A streptococci by the use of DNA amplification and non-radioactive allele-specific oligonucleotide probes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 119:19-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lancefield, R. C. 1962. Current knowledge of type-specific M antigens of group A streptococci. J. Immunol. 89:307-313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maxted, W. R., J. P. Widdowson, and C. A. Fraser. 1973. Antibody to streptococcal opacity factor in human sera. J. Hyg. (London) 71:35-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moses, A. E., C. Hidalgo-Grass, M. Dan-Goor, J. Jaffe, I. Shetzigovsky, M. Ravins, Z. Korenman, R. Cohen-Poradosu, and R. Nir-Paz. 2003. emm typing of M nontypeable invasive group A streptococcal isolates in Israel. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4655-4659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Musser, J. M., V. Kapur, J. Szeto, X. Pan, D. S. Swanson, and D. R. Martin. 1995. Genetic diversity and relationships among Streptococcus pyogenes strains expressing serotype M1 protein: recent intercontinental spread of a subclone causing episodes of invasive disease. Infect. Immun. 63:994-1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Brien, K. L., B. Beall, N. L. Barrett, P. R. Cieslak, A. Reingold, M. M. Farley, R. Danila, E. R. Zell, R. Facklam, B. Schwartz, and A. Schuchat. 2002. Epidemiology of invasive group A streptococcus disease in the United States, 1995-1999. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35:268-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perea-Mejia, L. M., A. E. Inzunza-Montiel, and A. Cravioto. 2002. Molecular characterization of group A Streptococcus strains isolated during a scarlet fever outbreak. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:278-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perks, E. M., and R. T. Mayon-White. 1983. The incidence of scarlet fever. J. Hyg. (London) 91:203-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seppala, H., Q. He, M. Osterblad, and P. Huovinen. 1994. Typing of group A streptococci by random amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1945-1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skjold, S. A., L. W. Wannamaker, D. R. Johnson, and H. S. Margolis. 1983. Type 49 Streptococcus pyogenes: phage subtypes as epidemiological markers in isolates from skin sepsis and acute glomerulonephritis. J. Hyg. (London) 91:71-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smoot, J. C., E. K. Korgenski, J. A. Daly, L. G. Veasy, and J. M. Musser. 2002. Molecular analysis of group A Streptococcus type emm18 isolates temporally associated with acute rheumatic fever outbreaks in Salt Lake City, Utah. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1805-1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spencer, R. C. 1995. Invasive streptococci. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 14(Suppl. 1):S26-S32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stanley, J., D. Linton, M. Desai, A. Efstratiou, and R. George. 1995. Molecular subtyping of prevalent M serotypes of Streptococcus pyogenes causing invasive disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2850-2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swaminathan, B., T. J. Barrett, S. B. Hunter, and R. V. Tauxe. 2001. PulseNet: the molecular subtyping network for foodborne bacterial disease surveillance, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:382-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teixeira, L. M., R. R. Barros, A. C. Castro, J. M. Peralta, M. Da Gloria S. Carvalho, D. F. Talkington, A. M. Vivoni, R. R. Facklam, and B. Beall. 2001. Genetic and phenotypic features of Streptococcus pyogenes strains isolated in Brazil that harbor new emm sequences. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3290-3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson, E., R. A. Zimmerman, and M. D. Moody. 1968. Value of T-agglutination typing of group A streptococci in epidemiologic investigations. Health Lab. Sci. 5:199-207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan, J. J., C. C. Liu, W. C. Ko, S. Y. Hsu, H. M. Wu, Y. S. Lin, M. T. Lin, W. J. Chuang, and J. J. Wu. 2003. Molecular analysis of group A streptococcal isolates associated with scarlet fever in southern Taiwan between 1993 and 2002. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4858-4861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]