Abstract

Although rotavirus genotype P[6] is one of the three most common VP4 specificities associated with human infection, the relatively few sequence data available in public databases suggest that the genetic variability within P[6] might be presently unexplored. Thus far, two human P[6] lineages (M37-like and AU19-like) and a single porcine P[6] lineage (Gottfried-like) have been identified by phylogenetic analysis. Serologic studies demonstrated that these three lineages are antigenically distinct from each other, a finding based on which they were classified into three subtypes, P2A[6] (M37-like), P2B[6] (Gottfried-like), and P2C[6] (AU19-like). To study heterogeneity within this genotype, we selected for molecular characterization a total of six P[6] strains detected during an ongoing surveillance in Hungary. The variable region of the VP4 gene was subjected to sequencing and phylogenetic analysis. Our data indicated that these six strains fell into two phylogenetic lineages distinguishable from the human lineages M37-like and AU19-like and from the porcine lineage Gottfried-like. Further studies are needed to understand whether these two novel lineages are genuine human strains or might have originated from animal strains and to evaluate the antigenic relationship of the novel Hungarian P[6] strains to the three established subtypes.

Group A rotaviruses, members of the family Reoviridae, are the major cause of acute dehydrating gastroenteritis in children and young animals (7). The viral genome composed of 11 segments of double-stranded RNA is enclosed in a nonenveloped, icosahedral, triple-layered capsid. The outer capsid antigens, VP7 and VP4, carry the serotype and the genotype specificities and serve as a basis for the dual nomenclature. The specificities of VP7 are designated with a G (VP7 is a glycoprotein), while the specificities of VP4 are designated with a P (VP4 is a protease-sensitive protein). Based on nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences, at least 15 G genotypes and 23 P genotypes have been established. Due to the lack of adequate immunological reagents (i.e., type-specific monoclonal antibodies or hyperimmune sera), some of the P genotypes have not been characterized serologically and a dual classification by P serotypes (designated with unbracketed numbers) and P genotypes (designated with bracketed numbers) is presently used for VP4 characterization. Out of 23 different P genotypes, only 14 P serotypes and 3 subtypes have been identified (7, 14, 21, 23).

Thus far, at least 10 G types (G1 to G6, G8 to G10, and G12) and 11 P types (P[1], P[3] to P[6], P[8] to P[11], P[14], and P[19]) have been identified in humans. Most of these specificities can also be found in animals, suggesting that certain human G and P types, especially those that are rarely detected, might have originated from animal strains either by direct interspecies transmission or by reassortment of cognate genes between heterologous and homologous strains. Serotypes G6 and G8, identified frequently in ruminants, or serotype G5, common in pigs but rare in humans, exemplify this hypothesis (2, 4, 6, 11). Although direct epidemiological evidence is still lacking, studies based on full genome hybridization and, more recently, on sequence and phylogenetic analysis seem to support the hypothesis that interspecies transmission may occur (4, 13, 29), even though such analyses usually cannot demonstrate direct evolutionary ancestry between recent animal and human strains. Indeed, gene sequences of animal strains segregate in most instances apart from those of human strains, suggesting either a strong diversification after the host switching or unequal distribution of distinct phylogenetic lineages in different hosts.

Early molecular epidemiological data together with recent surveillance studies identified five predominant G types (G1 to G4 and G9) and three common P types (P[4], P[6], and P[8]) mainly in six combinations (P[8],G1; P[4],G2; P[8],G3; P[8],G4; P[6],G9; and P[8],G9) to have clinical and epidemiological significance, particularly in temperate climates. By extrapolation of the data collected from international reports, these six strains are responsible for more than 90 to 95% of all hospitalization cases, while the remaining 5 to 10% of cases are associated with unusual combinations of the common P and G types (e.g., P[4],G1; P[6],G3; or P[8],G2) and with rare strains, some of which seem to have primarily local relevance (e.g., P[9],G6 in Hungary or P[8],G5 in South America). Although epidemiological observations suggest the existence of genetic linkages between the most common human VP4 and VP7 specificities (genotype P[8] is in linkage with the G1, G3, G4, and G9 specificities, whereas genotype P[4] is associated mainly with the G2 specificity), in this regard the relatively prevalent human P type, P[6], may represent an exception based on data that it has been found to be in association with most of the human VP7 specificities (5, 6, 13, 29).

During the past two decades, the epidemiological role of genotype P[6] has been substantially reconsidered. In early studies P[6] strains were detected exclusively from children with asymptomatic infection, suggesting that the P[6] specificity is associated with virus attenuation and, therefore, raising hopes that such strains may serve as components of future vaccine candidates (8, 32). However, subsequent epidemiological investigations identified P[6] strains as important human pathogens. To date, P[6] strains have been detected from both asymptomatic neonatal infections and symptomatic infantile infections in association with a wide variety of G types (5, 6, 13, 18, 29). At present there is no epidemiological data on neonatal asymptomatic infections in Hungary; however, genotype P[6] strains, in linkage with G4 specificity, have been sporadically identified from episodes of gastroenteritis of infants and young children (2).

Although P[6] is one of the three most prevalent VP4 genotypes in humans (6), the relatively few sequence data available in the public databases suggest that the heterogeneity within this genotype might be presently unexplored. Sequencing studies have demonstrated that almost all the human P[6] strains detected worldwide belong to one lineage, M37-like. However, substantial differences were observed in the VP8* sequences of two additional P[6] strains, namely, AU19, a unique human G1 rotavirus displaying a supershort RNA electropherotype that was isolated from a child affected with severe diarrhea and dehydration in Japan (26), and the porcine G4 strain, Gottfried, that was originally isolated from the intestinal content of a suckling pig with diarrhea (3). These findings indicate that strains AU19 and Gottfried may be considered prototypes of two additional P[6] lineages (26) and also suggest that the P[6] VP4 gene has undergone genetic and antigenic drift, similar to what has been described for the P[8] VP4 gene and for the G1, G3, G4, G6, and G9 VP7 genes (4, 12, 16, 17, 22, 24, 25, 34, 36). Interestingly, all three lineages of genotype P[6] represent serologically distinct subtypes, designated P2A[6] (M37-like) and P2C[6] (AU19-like) for the human strains and P2B[6] (Gottfried-like) for the porcine strain (20, 26).

In order to gain further insights into the genetic variability within genotype P[6], in this study we sequenced and analyzed partial sequences of the VP4 gene (VP8*) of P[6],G4 strains identified during an ongoing surveillance in Hungary.

Rotavirus-positive stool samples collected between 1992 and 2002 from children with diarrhea were serotyped and genotyped as was previously reported (2). Based on the genotype profile we randomly selected a total of six P[6],G4 strains for analysis. The laboratory work and subsequent computer analysis consisted of the following steps. Briefly, viral RNA was extracted using the guanidine thiocyanate/Glass Milk method as previously described (9). The RNA was heat denatured in the presence of the VP4-specific consensus primer (Con3), chilled immediately on ice, and subsequently reverse transcribed using the avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega). The resulting cDNA strand was amplified with Taq DNA polymerase (Promega) with primers Con3 and Con2 (9). The amplicons were electrophoresed in a low-melting-point agarose gel, subsequently excised, and extracted using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN). Cycle sequencing was carried out using the BigDye 1.1 kit (Applied Biosystems) with primers utilized in the PCR. Dye-labeled products were precipitated with ethanol in the presence of sodium acetate and then were dried. The products were subsequently resuspended in formamide and then run on an automated sequence analyzer (type 3100; ABI Prism). Raw sequence data were edited with the GeneDoc 1.1 program (27). Related sequences were searched in the public databases using the BLAST algorithm (1), and an alignment was made from our sequences and the downloaded sequences with the ClustalW algorithm in DAMBE software (35). The phylogenetic analysis was performed with the MEGA2 program using the p-distance algorithm (obtained by dividing the number of nucleotide differences by the total number of nucleotides compared) and the neighbor-joining method supported by bootstrap analysis (19).

The primer pair Con3/Con2 amplifies a product of about 880 bp in length (9), including the hypervariable region and a small fragment of the conserved region of the VP4 gene, called VP8* and VP5*, respectively. Our human P[6] strains gave amplicons of the expected sizes (data not shown). BLAST search identified the closest relatives among P[6] strains, demonstrating that our strains belong to genotype P[6]. This result confirmed the genotyping results obtained by multiplex reverse transcription-PCR (2 and unpublished data). Sequence comparison and phylogenetic analyses (Table 1 and Fig. 1) indicated, however, that each of these six strains was distinct from the human P[6] strains characterized previously. Indeed, phylogenetic analysis identified at least five separate lineages. In agreement with previous studies, the vast majority of human strains clustered in a single large lineage, M37-like, while two minor lineages, represented each by a single strain, were the human AU19-like and the porcine Gottfried-like lineages. The Hungarian human P[6],G4 strains clustered in two novel lineages, designated lineage IV (designated for the BP1198/98-like strains) and lineage V (designated for the BP720/93-like strains), a phylogenetic finding that was statistically supported by bootstrap analysis (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Distance matrix of sequence divergence within the VP8* gene (spanning nt 200 to 700 and aa 65 to 230) of P[6] strains

| Strain | Divergence (%) for straina:

|

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M37 | US1205 | RV3 | ST3 | MW23 | I076 | 6342 LP/99 | CH9 | Sc143 | AU19 | BP1198/98 | BP1338/99 | BP271/00 | BP720/93 | BP1227/02 | BP1231/02 | Gottfried | |

| M37 | 5.2 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 5.6 | 19.9 | 16.7 | 16.3 | 16.3 | 18.3 | 18.7 | 18.5 | 22.1 | |

| US1205 | 6.1 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 7.2 | 1.4 | 6.8 | 2.0 | 19.3 | 16.3 | 15.9 | 15.9 | 18.5 | 19.7 | 18.7 | 22.3 | |

| RV3 | 3.0 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 20.1 | 16.5 | 16.1 | 16.1 | 18.5 | 18.9 | 18.7 | 22.5 | |

| ST3 | 4.2 | 7.9 | 3.6 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 20.7 | 16.9 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 18.7 | 18.5 | 18.3 | 22.9 | |

| MW23 | 6.1 | 1.8 | 4.8 | 8.5 | 7.4 | 2.0 | 7.0 | 2.6 | 20.1 | 16.9 | 16.5 | 16.5 | 19.1 | 19.9 | 18.9 | 22.9 | |

| I076 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 6.1 | 4.8 | 7.2 | 1.6 | 7.4 | 22.5 | 19.1 | 18.3 | 18.3 | 20.3 | 20.7 | 20.1 | 24.9 | |

| 6342 LP/99 | 6.1 | 2.4 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 3.0 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 1.8 | 20.1 | 16.5 | 16.1 | 16.1 | 18.7 | 19.5 | 18.9 | 22.5 | |

| CH9 | 7.9 | 12.1 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 12.1 | 9.7 | 12.7 | 7.4 | 22.5 | 18.7 | 17.9 | 17.9 | 19.7 | 20.1 | 19.5 | 24.3 | |

| Sc143 | 6.1 | 2.4 | 5.5 | 7.9 | 3.0 | 5.5 | 2.4 | 12.7 | 20.7 | 17.1 | 16.7 | 16.7 | 18.9 | 19.7 | 19.1 | 23.1 | |

| AU19 | 20.0 | 18.2 | 18.8 | 22.4 | 19.4 | 20.0 | 20.6 | 26.1 | 20.0 | 17.3 | 17.1 | 17.1 | 19.3 | 18.9 | 19.9 | 24.5 | |

| BP1198/98 | 14.5 | 15.2 | 13.9 | 16.4 | 15.8 | 15.2 | 15.2 | 21.2 | 14.5 | 15.2 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 15.7 | 15.9 | 16.1 | 19.9 | |

| BP1338/99 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 12.7 | 15.2 | 14.5 | 13.9 | 13.9 | 18.8 | 13.3 | 15.8 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 14.9 | 14.7 | 15.7 | 20.1 | |

| BP271/00 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 12.7 | 15.2 | 14.5 | 13.9 | 13.9 | 18.8 | 13.3 | 15.8 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 15.3 | 15.1 | 15.7 | 19.5 | |

| BP720/93 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 21.2 | 18.2 | 15.2 | 11.5 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 22.1 | |

| BP1227/02 | 18.2 | 19.4 | 18.2 | 19.4 | 19.4 | 19.4 | 19.4 | 21.8 | 18.8 | 12.7 | 10.3 | 8.5 | 8.5 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 19.9 | |

| BP1231/02 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 17.6 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 21.2 | 18.2 | 15.8 | 11.5 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 22.1 | |

| Gottfried | 23.6 | 24.8 | 23.6 | 25.5 | 24.8 | 23.6 | 24.8 | 27.9 | 24.2 | 23.6 | 19.4 | 18.2 | 18.2 | 20.0 | 18.2 | 20.0 | |

Nucleotide divergence is shown in the upper right area, and amino acid divergence is shown in the lower left area.

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree for the VP8* fragment of VP4 gene (nt 200 to 700) of strains with P[6] specificity by using the neighbor-joining algorithm. Bootstrap values greater than 60% are indicated at the branch nodes. The scale bar is proportional to the genetic distance. An outgroup sequence (P[19]) was included to better understand the phylogenetic relationships among P[6] strains. Data about the associated G serotype, the country of isolation, and whether the strain was identified from symptomatic (S) or asymptomatic (AS) infections are displayed where information was available. Unknown data are indicated with a question mark.

Based on the tree topology we compiled a distance matrix (Table 1) in which selected representatives of the M37-like human strains, the AU19 strain, the Gottfried strain, and all six Hungarian P[6] strains were included. Because of the unequal length of sequences available for distinct strains, the analysis was performed with a shorter region spanning nucleotide (nt) 200 to 700 and amino acid (aa) 65 to 230. Along with this fragment the sequence divergence within the M37-like lineage was 1.4 to 7.4% (nt) and 2.4 to 12.7% (aa). Sequence variation among strains within the Hungarian lineage IV (nt, ≤2.2%; aa, ≤3.6%) and lineage V (nt, ≤6.0%; aa, ≤4.8%) fell virtually into the same range (Table 1). In contrast, divergence between strains of lineage IV and strains belonging to the four other lineages were considerably higher (nt, 14.7 to 20.1%; aa, 8.5 to 21.2%). Comparable divergences were found between lineage V and the other lineages (nt, 14.7 to 22.1%; aa, 8.5 to 21.8%; Table 1). In this comparison the lowest interlineage variation was found between strains of lineage IV and lineage V (nt, 14.7 to 16.1%; aa, 8.5 to 11.5%; Table 1). When a longer sequence (795 bp; nt 56 to 850) was analyzed, we found essentially the same ranges of divergence with both the M37-like human strains (lineage IV, 14.7 to 17.1% for nt and 9.8 and 16.3% for aa; lineage V, 15.5 to 17.9% for nt and 12.9 to 17.0% for aa) and the Gottfried strain (lineage IV, 19.4 to 19.9% for nt and 15.2 to 15.9% for aa; lineage V, 18.4 to 19.5% for nt and 15.2 to 16.3% for aa; data not shown). Overall, the sequence variation for the partial VP4 gene fell approximately into the same ranges in any interlineage comparison, except for lineage IV and lineage V strains, which were somewhat more closely related to each other.

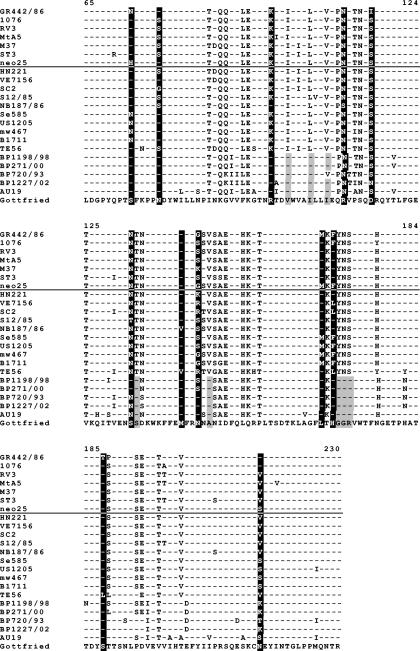

Direct inspection of the sequence alignment (Fig. 2) revealed that all Hungarian P[6] strains and the atypical Japanese human P[6] strain share several amino acid substitutions with the porcine strain Gottfried (aa 98, R instead of K; aa 101, V instead of I; aa 105, I instead of L; aa 108, I instead of V; aa 134, S instead of T; aa 147, A instead of V; aa 170, G instead of Y; aa 171, G instead of N; aa 172, R instead of S). Some residues (aa 91, V instead of I; aa 196, V instead of I) were conserved between the M37-like strains and the porcine strain Gottfried, but they were absent in the other human lineages. All these changes may represent a reversion to or, presumably, retention of the ancestral sequence, suggesting that the three minor human lineages are in an intermediate position between the major human M37-like lineage and the porcine virus prototype Gottfried. Thus, assuming that the conserved sites shared by several lineages represent the ancestral sequence, the presence of conserved residues observed exclusively in the human lineages very likely represent amino acid sites that were exposed to more intensive genetic drift in pigs. Alternatively, these conserved amino acids might have importance in the process of adaptation to the human host by the human P[6] lineages.

FIG. 2.

An alignment for the partial amino acid sequences of genotype P[6] specificity. The amino acid sites addressed to be involved in attenuation are highlighted (white letters on black background) (5, 28). The residues conserved across the minor lineages of human P[6] strains and the porcine strain Gottfried are also shaded (gray). The line separates the asymptomatic strains (above) and symptomatic strains (below). Only substitutions distinct from the consensus (Gottfried) are shown.

Attempts to understand the molecular basis of rotaviral pathogenicity have addressed VP4 as a possible determinant of virulence. VP4 has a wide spectrum of biological activities: it mediates cell attachment, bears serotype specificities, evokes neutralization and protective antibodies, influences growth characteristics in cell culture, and appears to determine host-range restriction (7). The finding that genotype P[6] strains may be recovered from asymptomatic and symptomatic neonatal infections alike raised the possibility that this genotype might represent an adequate model to study the genetic background of VP4-associated virulence. A number of research groups analyzed virulent community rotaviruses and avirulent nursery rotaviruses circulating in given geographic areas, and some of them identified conserved amino acid substitutions in the VP4 gene between these two groups of strains (5, 18, 28). In contrast, a study by Santos et al. (30) did not identify consistent amino acid substitutions between silent and virulent isolates, although these authors analyzed strains of geographically distinct origin. The alignment of partial amino acid sequences we compiled from a number of strains detected in different parts of the world was in agreement with this latter study in demonstrating a lack of consistent amino acid substitution patterns between asymptomatic and symptomatic strains (Fig. 2). As these conflicting findings do not allow linking any particular amino acid substitution(s) to changes in virulence, the relative importance of these amino acid variations remains unclear.

In addition to the lack of consistent amino acid change patterns, neither phylogenetic studies nor antigenic characterization identified significant differences in the VP4 gene among symptomatic and asymptomatic P2A[6] rotavirus strains (15; see also Fig. 1). In contrast, the VP4 genes of the unique human P[6] strain, AU19, and the porcine Gottfried strain could be distinguished both phylogenetically and antigenically, and therefore they were classified as P2C[6] and P2B[6], respectively (20, 26). Because there is no absolute correlation between P genotypes and P serotypes (7), the lack of antigenic data on the novel genotype P[6] strains does not allow prediction of their serotype specificities. Serologic and molecular characterization of group A rotavirus isolates indicate that strains belonging to a particular P serotype usually share >89% amino acid identity in their full-length VP4 genes (10). However, exceptions to these data have been observed, e.g., for strains 69 M (P4[10]) and H-2 (P4[12]), which carry the same serotype specificity despite the relatively low amino acid sequence identity (85.3%; data not shown). Thus, although in this study we did not determine full-length VP4 genes, the finding that all three previously identified subtypes of P2[6] belong to separate genetic lineages warrants further studies to investigate the effect of amino acid substitutions on the antigenic properties of the novel P?[6] strains after their adaptation to cell culture.

In summary, in the present study we described two formerly undetected lineages of genotype P[6] in humans. Representatives of the globally distributed M37-like P[6] lineage were not identified among the few isolates characterized. Thus, we were not able to assess the relative epidemiological importance of these novel strains from our study. Nonetheless, our results suggest that the variability within P[6] specificity is larger than previously thought. Collection of comprehensive sequence data about genotype P[6] strains will be necessary to reveal the significance of these strains in Hungary and other parts of the world. It would also be useful to understand whether these two novel lineages include genuine human strains or whether they originated from animal strains by interspecies transmission. The presence of several amino acid changes in the Hungarian and the Japanese strains' VP8* gene compared to the sequence of the porcine P[6] prototype is compatible with the hypothesis that the P[6] VP4 gene has been introduced into the human pool of rotavirus genes on a number of occasions by multiple, independent reassortment events. Alternatively, a hypothesis could be that a single heterologous reassortment event (perhaps with porcine strains) occurred that was followed by different rates of diversification for each human lineage. According to this hypothesis different lineages may undergo various selective pressures and evolve less or more quickly, reaching a sort of evolutionary stasis when completely adapted to their host. Such a model has been formulated for influenza viruses, where avian strains, unlike mammalian strains, seem to possess low evolutionary rates, having reached an optimal adaptation in their primary host, the birds (31, 33).

Full-genome analysis by RNA-RNA hybridization or sequencing of selected genes may provide insights into the possible origin of the novel genotype P[6] rotaviruses.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers. Strains and GenBank accession of their partial VP4 gene are the following: strain BP720/93, accession no. AJ621503; BP1198/98, AJ621504; BP1338/99, AJ621507; BP271/00, AJ621502; BP1227/02, AJ621505; and BP1231/02, AJ621506.

Acknowledgments

We thank Judit Oksai for assistance in nucleotide sequencing. We are grateful to Athina Papa and Jon R. Gentsch for critically reading and correcting the manuscript.

This study was supported by the Hungarian Research Fund (OTKA; T032933).

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bányai, K., J. R. Gentsch, R. I. Glass, M. Új, I. Mihály, and G. Szücs. 2004. Eight-year survey of human rotavirus strains demonstrates circulation of unusual G and P types in Hungary. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:393-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bohl, E. H., K. W. Theil, and L. J. Saif. 1984. Isolation and serotyping of porcine rotaviruses and antigenic comparison with other rotaviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 19:105-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooney, M. A., R. J. Gorrel, and E. A. Palombo. 2001. Characterisation and phylogenetic analysis of the VP7 proteins of serotype G6 and G8 human rotaviruses. J. Med. Microbiol. 50:462-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunliffe, N. A., S. Rogerson, W. Dove, B. D. M. Thindwa, J. Greensill, C. D. Kirkwood, R. L. Broadhead, and C. A. Hart. 2002. Detection and characterization of rotaviruses in hospitalized neonates in Blantyre, Malawi. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1534-1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desselberger, U., M. Iturriza-Gómara, and J. J. Gray. 2001. Rotavirus epidemiology and surveillance, p. 125-147. In D. Chadwick and J. A. Goode (ed.), Gastroenteritis viruses. Novartis Foundation Symposium 238. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., West Sussex, England. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Estes, M. K. 2001. Rotaviruses and their replication, p. 1747-1785. In D. M. Knipe and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 8.Flores, J., K. Midthun, Y. Hoshino, K. Green, M. Gorziglia, A. Z. Kapikian, and R. M. Chanock. 1986. Conservation of the fourth gene among rotaviruses recovered from asymptomatic newborn infants and its possible role in attenuation. J. Virol. 60:972-979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gentsch, J. R., R. I. Glass, P. Woods, V. Gouvea, M. Gorziglia, J. Flores, B. K. Das, and M. K. Bhan. 1992. Identification of group A rotavirus gene 4 types by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:1365-1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorziglia, M., G. Larralde, A. Z. Kapikian, and R. M. Chanock. 1990. Antigenic relationships among human rotaviruses as determined by outer capsid protein VP4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:7155-7159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gouvea, V., and N. Santos. 1999. Rotavirus serotype G5: an emerging cause of epidemic childhood diarrhea. Vaccines 17:1291-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gouvea, V., R. C. Lima, R. E. Linhares, H. F. Clark, C. M. Nosawa, and N. Santos. 1999. Identification of two lineages (WA-like and F45-like) within the major rotavirus genotype P[8]. Virus Res. 59:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffin, D. D., T. Nakagomi, Y. Hoshino, O. Nakagomi, C. D. Kirkwood, U. D. Parashar, R. I. Glass, J. R. Gentsch, and the National Rotavirus Surveillance System. 2002. Characterization of nontypeable rotavirus strains from the United States: identification of a new rotavirus reassortant (P2A[6],G12) and rare P3[9] strains related to bovine rotaviruses. Virology 294:256-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoshino, Y., R. W. Jones, and A. Z. Kapikian. 2002. Characterization of neutralization specificities of outer capsid spike protein VP4 of selected murine, lapine, and human rotavirus strains. Virology 299:64-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoshino, Y., R. W. Jones, J. Ross, N. Santos, and A. Z. Kapikian. 2003. Human rotavirus strains bearing VP4 gene P[6] allele recovered from asymptomatic or symptomatic infections share similar, if not identical, VP4 neutralization specificities. Virology 316:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iturriza-Gomara, M., J. Green, D. W. G. Brown, U. Desselberger, and J. J. Gray. 2000. Diversity within the VP4 gene of rotavirus P[8] strains: implications for reverse transcription-PCR genotyping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:898-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin, Q., R. L. Ward, D. R. Knowlton, Y. B. Gabbay, A. C. Linhares, R. Rappaport, P. A. Woods, R. I. Glass, and J. R. Gentsch. 1996. Divergence of VP7 genes of G1 rotaviruses isolated from infants vaccinated with reassortant rhesus rotaviruses. Arch. Virol. 141:2057-2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirkwood, C. D., B. S. Coulson, and R. F. Bishop. 1996. G3P2 rotaviruses causing diarrhoeal disease in neonates differ in VP4, VP7 and NSP4 sequence from G3P2 strains causing asymptomatic neonatal infection. Arch. Virol. 141:1661-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar, S., K. Tamura, I. B. Jakobsen, and M. Nei. 2001. MEGA2: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software. Bioinformatics 17:1244-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, B., and M. Gorziglia. 1993. VP4 serotype of the Gottfried strain of porcine rotavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:3075-3077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liprandi, F., M. Gerder, Z. Bastidas, J. A. Lopez, F. H. Pujol, J. E. Ludert, D. B. Joelsson, and M. Ciarlet. 2003. A novel type of VP4 carried by a porcine rotavirus strain. Virology 315:373-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martella, V., A. Pratelli, G. Greco, M. Gentile, P. Fiorente, M. Tempesta, and C. Buonavoglia. 2001. Nucleotide sequence variation of the VP7 gene of two G3 type rotaviruses isolated from dogs. Virus Res. 74:17-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martella, V., M. Ciarlet, A. Camarda, A. Pratelli, M. Tempesta, G. Greco, A. Cavalli, G. Elia, N. Decaro, V. Terio, G. Bozzo, M. Camero, and C. Buonavoglia. 2003. Molecular characterization of the VP4, VP6, VP7, and NSP4 genes of lapine rotaviruses identified in Italy: emergence of a novel VP4 genotype. Virology 314:358-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martella, V., V. Terio, S. Arista, G. Elia, M. L. Corrente, A. Madio, A. Pratelli, M. Tempesta, A. Cirani, and C. Buonavoglia. 2004. Nucleotide variation in the VP7 gene affects PCR genotyping of G9 rotaviruses identified in Italy. J. Med. Virol. 72:143-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maunula, L., and C. H. von Bonsdorff. 1998. Short sequences define genetic lineages: phylogenetic analysis of group A rotaviruses based on partial sequences of genome segments 4 and 9. J. Gen. Virol. 79:321-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakagomi, T., Y. Horie, Y. Koshimura, H. B. Greenberg, and O. Nakagomi. 1999. Isolation of a human rotavirus strain with a super-short RNA pattern and a new P2 subtype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1213-1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholas, K. B., H. B. Nicholas, and D. W. I. Deerfield. 1997. GeneDoc: analysis and visualization of genetic variation. EMBNET News 4:1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pager, C. T., J. J. Alexander, and A. D. Steele. 2000. South African G4P[6] asymptomatic and symptomatic neonatal rotavirus strains differ in their NSP4, VP8*, and VP7 genes. J. Med. Virol. 62:208-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahman, M., K. De Leener, T. Goegebuer, E. Wollants, I. van der Donck, L. van Hoovels, and M. van Ranst. 2003. Genetic characterization of a novel, naturally occurring recombinant human G6P[6] rotavirus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2088-2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Santos, N., V. Gouvea, M. C. Timenetsky, H. F. Clark, M. Riepenhoff-Talty, and A. Garbarg-Chenon. 1994. Comparative analysis of VP8* sequences from rotaviruses possessing M37-like VP4 recovered from children with and without diarrhoea. J. Gen. Virol. 75:1775-1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki, Y., and M. Nei. 2002. Origin and evolution of influenza virus hemagglutinin genes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 19:501-509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vesikari, T., R. Ruuska, H. P. Koivu, K. Y. Green, J. Flores, and A. Z. Kapikian. 1991. Evaluation of the M37 human rotavirus vaccine in 2- to 6-month-old infants. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 10:912-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Webster, R. G. 2002. The importance of animal influenza for human disease. Vaccine 20:16-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wen, L., H. Ushijima, J. Kakizawa, Z. Y. Fang, O. Nishio, S. Morikawa, and T. Motohiro. 1995. Genetic variation in VP7 gene of human rotavirus serotype 2 (G2 type) isolated in Japan, China, and Pakistan. Microbiol. Immunol. 39:911-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia, X., and Z. Xia. 2001. DAMBE: data analysis in molecular biology and evolution. J. Heredity 92:371-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xin, K. Q., S. Morikawa, Z. Y. Fang, A. Mukoyama, K. Okuda, and H. Ushijima. 1993. Genetic variation in VP7 gene of human rotavirus serotype 1 (G1 type) isolated in Japan and China. Virology 197:813-816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]