Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype strains are highly prevalent in Asian countries and in the territory of the former Soviet Union. They are increasingly reported in other areas of the world and are frequently associated with tuberculosis outbreaks and drug resistance. Beijing genotype strains, including W strains, have been characterized by their highly similar multicopy IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns, deletion of spacers 1 to 34 in the direct repeat region (Beijing spoligotype), and insertion of IS6110 in the genomic dnaA-dnaN locus. In this study the suitability and comparability of these three genetic markers to identify members of the Beijing lineage were evaluated. In a well-characterized collection of 1,020 M. tuberculosis isolates representative of the IS6110 RFLP genotypes found in The Netherlands, strains of two clades had spoligotypes characteristic of the Beijing lineage. A set of 19 Beijing reference RFLP patterns was selected to retrieve all Beijing strains from the Dutch database. These reference patterns gave a sensitivity of 98.1% and a specificity of 99.7% for identifying Beijing strains (defined by spoligotyping) in an international database of 1,084 strains. The usefulness of the reference patterns was also assessed with large DNA fingerprint databases in two other European countries and for identification strains from the W lineage found in the United States. A standardized definition for the identification of M. tuberculosis strains belonging to the Beijing/W lineage, as described in this work, will facilitate further studies on the spread and characterization of this widespread genotype family of M. tuberculosis strains.

Despite mass Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination and antituberculosis drugs, tuberculosis is one of the major killers among infectious diseases, causing about eight million cases and two to three million deaths annually (10). Current trends suggest that these numbers could rise to 12 million and 4 million, respectively, by the year 2010 (17). DNA fingerprinting of the causative agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, has revealed that in high-incidence areas, where more than 97% of these tuberculosis deaths occur, particular M. tuberculosis genotypes predominate, suggesting selective advantages of these strains (15, 19, 36, 37). It has been hypothesized that the BCG-induced immunological defense may protect against most M. tuberculosis strains but not against selected genotypes (called escape variants), such as M. tuberculosis Beijing isolates (15, 23, 37). Recent studies in a BALB/c mouse model demonstrated differential interaction of various M. tuberculosis strains with the host immune system and suggested a lower efficacy of BCG vaccination against infections by Beijing genotype strains (reference 23 and unpublished data).

In 1995, the genetically highly conserved Beijing family of M. tuberculosis strains was described. Isolates assigned to this genotype family had highly similar multibanded IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns and identical spoligo patterns. This family of strains was designated the Beijing family because the highest density of this group of M. tuberculosis strains was found in the Beijing, China, area, where more than 85% of the M. tuberculosis isolates belonged to this family. Subsequently, this family has been shown to be highly prevalent in other Asian countries (2, 37). In Vietnam the occurrence of Beijing family strains was significantly correlated with young tuberculosis patients, suggesting recent transmission (1). In some areas, such as Vietnam, Cuba, and Estonia, Beijing strains were found to be strongly associated with drug resistance (1, 4, 7, 20). This is consistent with the prolific spread of (multidrug)-resistant variants of the W strain in the early 1990s in North America (3). W strains exhibit highly similar IS6110 RFLP patterns and identical, characteristic spoligo patterns. The multidrug-resistant W strains have two copies of IS6110 in the NTF region of the genome and can therefore be easily identified by multiplex PCR (27). It is now known that the W family and Beijing family strains represent the same genotype family of M. tuberculosis, which was concurrently identified in the American (4) and Asian (37) continents. In this study we refer to both groups of strains as the Beijing family (2, 21). A second group of clinical isolates with distantly related IS6110 RFLP profiles have been determined to belong to the Beijing/W lineage by other molecular techniques and are referred to as ancestral isolates (25; P. J. Bifani et al., unpublished data). The ancestral isolates share a common predecessor with Beijing family strains, as illustrated by the extensive shared molecular characteristics, including chromosomal insertions and deletions and single nucleotide polymorphisms (28). However, the ancestral isolates differ in IS6110 RFLP pattern from the Beijing family strains, given that they have diverged early during the course of evolution.

The widely distributed (but not universal) association of drug resistance and the Beijing genotype suggests that these strains may have a particular propensity for acquiring drug resistance (13). Recently, it was reported that Beijing strains carry mutations in putative mutator genes, and this may explain a higher adaptability of these bacteria to stress conditions such as exposure to antituberculosis drugs and the hostile intracellular environment (28).

A recent systematic review of the published literature demonstrated the worldwide ubiquity of the Beijing strains and their frequent association with outbreaks and drug resistance. Definite conclusions on the extent of spread and associations with drug resistance, however, could not yet be drawn. This was due to the limited amount of information available from most areas of the world, the possible biases in many of the published reports, and the absence of standard definitions and study designs (13). It is therefore our objective to propose a working definition for the standardized identification of members of the Beijing/W lineage.

M. tuberculosis Beijing family strains can be recognized by the combination of two genetic markers in addition to closely related IS6110 RFLP patterns containing a high number of bands (19, 26, 29, 37): (i) identical spoligo patterns showing hybridization to spacers 35 to 43 (5, 19, 26, 29, 37) and (ii) a specific A1 insertion of an IS6110 element in the origin of replication (intergenic dnaA-dnaN region) (21). A few outliers that do not meet all of the above-suggested criteria for identification have also been described, such as strains with “Beijing-like” spoligo patterns (5) (lacking one or more of the last nine spacers) and strains that harbor the Beijing spoligotype and the A1 insertion but differ significantly in their IS6110 banding patterns from regular Beijing strains (21).

We investigated the utility of the above-described molecular markers for identification of Beijing family strains, and we propose a definition for the identification of members of the Beijing lineage in international databases by using IS6110 RFLP genotyping and spoligotyping.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The specificities of three molecular markers described for the identification of isolates belonging to the Beijing family were evaluated by using the M. tuberculosis strain collection maintained at the National Institute of Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Bilthoven, The Netherlands. Based on this evaluation, a working definition of the Beijing lineage was established. This definition was subsequently assessed through analysis of an international database, a Danish database, and a German database. The results of molecular typing of Beijing lineage strains from this study were compared with those obtained from database of the Public Health Research Institute (PHRI) Tuberculosis Center, Newark, N.J.

Study populations. (i) The Netherlands.

The study population consisted of M. tuberculosis strains isolated from all culture-positive tuberculosis cases in The Netherlands during the period spanning January 1993 through December 1999. For the purpose of this study, a single sample from each of the IS6110 RFLP clusters was included. All M. tuberculosis complex isolates showing a unique combination of IS6110 RFLP and spoligo pattern were included in the study, resulting in 2,345 strains. Table 1 shows an overview of the tests that were performed on these 2,345 strains. In The Netherlands, more than 55% of diagnosed tuberculosis cases are in foreign-born individuals (33).

TABLE 1.

Tests performed on the data set from The Netherlands

| Group (n) | Spoligotyping

|

Region A RFLP

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. tested/total | Results (n) | No. tested/total | No. Beijing/no. tested | |

| All (2,345) | 1,020/2,345 | B (142) | 68/142 | 64/68 |

| B-like (14) | 14/14 | 14/14 | ||

| Non-B (864) | 356/864 | 14/356 | ||

| 1,236 Not done (1,236) | 422/1,236 | 0/422 | ||

| Clade 47 (124) | 124/124 | B (120) | 52/120 | 48/52 |

| B-like (4) | 4/4 | 4/4 | ||

| Clade 47 related (35) | ||||

| 52% similarity | 16/16 | Non-B (16) | 3/16 | 0/3 |

| >60% similarity | 19/19 | B (12) | 6/12 | 6/6 |

| B-like (6) | 6/6 | 6/6 | ||

| Non-B (1) | 1/1 | 0/1 | ||

| Nonclade isolates (640) | 551/640 | Non-B (551) | 254/551 | 5/254 |

| Non-clade 47 clade isolates (1,530) | 294/1,530 | B, clade 61 (7) | 7/7 | 7/7 |

| B-like, clade 61 (1) | 1/1 | 1/1 | ||

| Non-B (286) | 88/286 | 9/88 | ||

| Not done (1,236) | 422/1,236 | 0/422 | ||

| Clade 61 related (16) | 16/16 | B (3) | 3/3 | 3/3 |

| B-like (3) | 3/3 | 3/3 | ||

| Non-B (10) | 10/10 | 0/10 | ||

(ii) W lineage isolates from PHRI collection.

Twelve representative samples of the Beijing/W lineage (3, 21) were included in this study as references. These samples were chosen from the PHRI strain collection as the most distantly related Beijing strains (with 50 to 60% similarity on basis of IS6110 RFLP) sharing the Beijing spoligotype and the A1 insertion in the dnaA-dnaN region. They were selected from the PHRI database, which contains 770 distinct IS6110 variants of the W strains. One group of isolates includes diverse ancestral members of the Beijing/W phylogenetic lineage (25; Bifani et al., unpublished data). These isolates exhibit spoligo patterns characteristic of the Beijing family and contain the A1 IS6110 insertion, but their IS6110 RFLP patterns are different from those of the Beijing family (37) and the W family, as previously discussed (2). This set of ancestral isolates included TN5195-001, TN11265-LB, TN8222-HD6, TN4948-AM, TN10545-KY, TN4862-CI1, TN6595-CK, TN12766-N4, and 14439-N4. In contrast, the second group of strains, including W1, W6, and W13, share high similarities in their IS6110 RFLP patterns with other, regular Beijing family isolates.

(iii) International database.

The international database held at the RIVM contains both IS6110 RFLP and spoligo patterns of 1,084 M. tuberculosis complex isolates. These isolates originated from 40 different countries covering all continents except Australasia. Most isolates originated from Asia (n = 682; 62.9%), where the Beijing family is most prevalent (13). Many of these isolates have been described in previous studies (7, 8, 19, 26, 29, 31, 37).

(iv) German database.

The German database consisted of 452 IS6110 RFLP patterns of multidrug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains isolated from an equal number of patients in Germany in the period between 1995 and 2001 (T. Kubica et al., submitted for publication). Nineteen percent of the isolates were from Germans, and 65% originated from foreign-born individuals, while no data were available for the remaining 16%. Twenty of the 452 isolates contained fewer than five IS6110 copies. The remaining isolates exhibited 263 distinct IS6110 RFLP types, and 240 isolates were representatives of 47 different IS6110 clusters.

(v) Danish database.

The Danish database contained 4,102 IS6110 RFLP patterns retrieved from 3,936 tuberculosis patients who were notified as having tuberculosis in the period from 1992 through 2001, representing 97% of all M. tuberculosis complex-positive patients in Denmark. Fifty-seven percent of the patterns (2,334 of 4,102) originated from foreign-born patients from 90 different nations: 1,285 (31.3%) from African-born patients, 651 (15.9%) from Asian-born patients, and 183 (4.5%) from patients born in the former USSR. Fifty-eight percent of the RFLP patterns were grouped in 336 DNA fingerprint clusters.

DNA fingerprinting.

IS6110- and polymorphic GC-rich sequence-based RFLP genotyping was performed by the standardized methods described previously (30, 34, 35). Membranes containing PvuII restriction fragments were rehybridized with the region A targeting probe described by Kurepina et al. (21) by using the Alk-Phos kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Rehybridization with this probe was done to check for Beijing-specific A1 insertions of IS6110 in the dnaA-dnaN locus.

The presence of 43 known spacer sequences in the direct repeat region was determined by spoligotyping (18, 37).

Not all of the samples in the German and Danish databases were subjected to both spoligotyping and IS6110 RFLP. Spoligotyping was used to confirm all IS6110 patterns likely to be from the Beijing lineage but was only done for a sample of those that were not detected by IS6110. On the basis of these parameters, IS6110-based definitions will tend to underestimate the true specificity but may overestimate sensitivity, in comparison with spoligotyping.

Computer-assisted analysis.

To analyze IS6110 RFLP patterns and to define clades, GelCompar software version 4.0 (Applied Maths, Ghent, Belgium) was used as described previously (14). Similarities were calculated by using the Dice coefficient, allowing 1.0% position tolerance. The Dice coefficient adds weight to the bands that are in common between two patterns and is calculated by the formula Sab = 2 × Nab/(Na + Nb), where S is the similarity between banding patterns a and b, Nab is the number of bands that patterns a and b have in common, Na is the number of bands in pattern a, and Nb is the number of bands in pattern b. The unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages was used for cluster analysis. Clades were defined as groups of five strains or more with related IS6110 patterns with at least 70% mutual similarity. Clusters were defined as groups of strains with 100% identical IS6110 RFLP patterns.

Bionumerics software (Applied Maths) was used to analyze both spoligo and RFLP patterns. IS6110, polymorphic GC-rich sequence, and spoligo patterns were analyzed as fingerprint types. The results of the region A probe hybridizations were divided into three groups: wild type (no IS6110 insertion and therefore a single band), Beijing-type (two bands of 8.55 and 3.36 kb, characteristic of the Beijing phylogenetic lineage), and other (two bands of other molecular sizes or three bands if more than one IS6110 insertion is present). The similarity among IS6110 RFLP patterns was determined by using the identification tool of the Bionumerics software, by which each isolate in turn is compared with all others in the database, using 1.0% band position tolerance, 1.0% optimization, and the Dice coefficient.

RESULTS

Recognition of Beijing family strains by IS6110 RFLP.

To determine if members of the Beijing family could be identified by a unique set of IS6110 RFLP patterns, we first used the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic averages to cluster the 2,345 different IS6110 RFLP patterns identified in the Dutch database. We identified 93 clades, each comprising at least five strains and sharing over 70% pattern similarity. Six hundred forty patterns were not assigned to clades.

Initially only clade 47, consisting of 124 isolates, was identified as the Beijing genotype family on the basis of the characteristic multibanded IS6110 RFLP (37). Ninety-seven percent (120 of 124) of the isolates in clade 47 had the nine-spacer spoligo pattern, consisting of spacers 35 to 43, characteristic of the Beijing family (5, 26, 29, 37). The identification of these 120 strains as members of the Beijing lineage was confirmed by analysis of an IS6110 insertion in the dnaA-dnaN region, the A1 insertion (21). Fifty-two strains representing all different branches from clade 47 were subjected to region A RFLP. Forty-eight of these strains had an RFLP pattern that is characteristic of Beijing strains (Table 2). The other four strains showed three bands in the region A RFLP pattern, indicative of two insertions of IS6110 in the dnaA-dnaN region; this polymorphism at region A has previously been reported for Beijing strains (21).

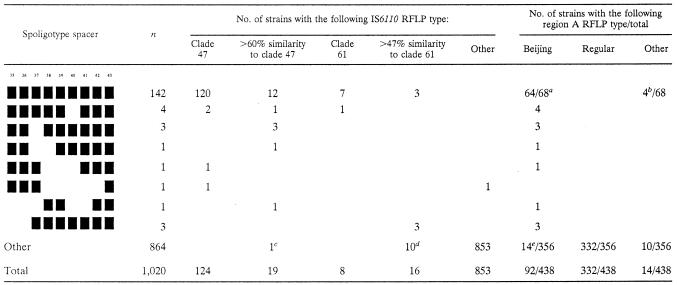

TABLE 2.

Correlation between spoligotype, IS6110 RFLP, and region A RFLP patterns among 1,442 different M. tuberculosis complex strains representing the breadth of M. tuberculosis genotypes in The Netherlands

The following strains were investigated: 52 strains of clade 47, six strains belonging to the group showing >60% similarity to clade 47, and all strains belonging to clade 61 or showing >47% similarity to clade 61.

These four strains belonged to RFLP clade 47 and showed hybridization with the region A probe to three PvuII restriction fragments, indicating two insertions of IS6110 in the dnaA-dnaN region.

The spoligo pattern of this strain contained 40 spacers, and the strain exhibited a regular region A RFLP pattern.

These 10 strains showed a regular region A RFLP pattern.

Fourteen out of the 356 strains, not showing a Beijing- or Beijing-like spoligo pattern, showed a Beijing- characteristic region A RFLP pattern. Nine of these strains originated from seven different clades on basis of IS6110 RFLP, other then clades 47 and 61.

The remaining four of the 124 clade 47 isolates had a Beijing-like spoligo pattern (5), i.e., a spoligo pattern closely related to the nine-spacer spoligo pattern, and a characteristic insertion in the dnaA-dnaN region (Table 2). We concluded that all clade 47 isolates belonged to the Beijing family.

Is the clade 47 IS6110 RFLP pattern specific for all strains of the Beijing family?

To determine whether only the IS6110 RFLP patterns of clade 47 (Fig. 1, group A3) are characteristic of the Beijing genotype family, the isolates of the five groups in the dendrogram (n = 35) with the highest similarity to clade 47 were subjected spoligotyping.

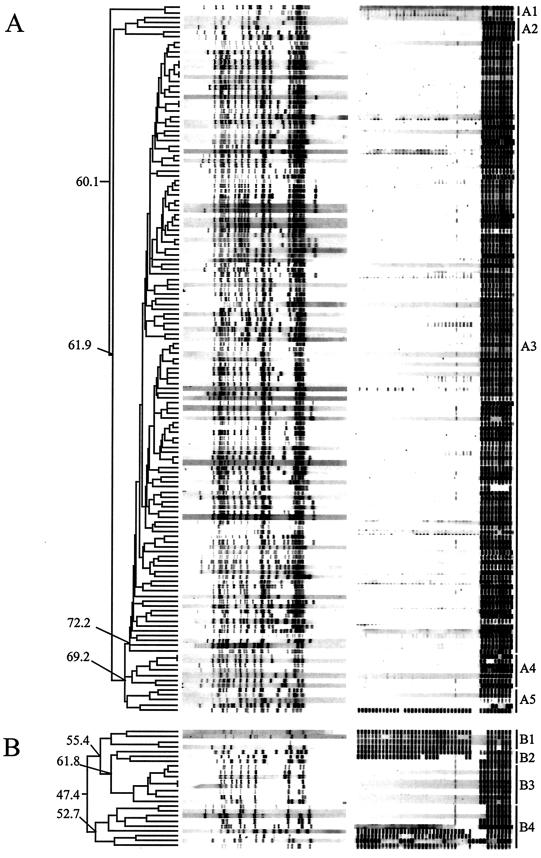

FIG.1.

For both panels A and B, the dendrogram (left) reflects the similarity of the IS6110 RFLP patterns. The IS6110 RFLP patterns (middle) are shown, with the PvuII restriction fragments depicted from high (left) to low (right) molecular weight. The spoligo patterns (right) are shown from spacer 1 to spacer 43 (left to right). Related groups of DNA fingerprints are marked A or B, followed by a number, to the right of the spoligo patterns. These groups mark the isolates that belong to certain branches of the dendrogram. Group A3 represents clade 47, and group B3 represents clade 61. For some branches in the dendrograms, the similarity between the branches is indicated as a percentage at the left of the dendrogram. The clade 47 (group A3) isolates and all except one of the isolates showing IS6110 RFLP patterns with 60% or more similarity to clade 47 patterns (groups A1, A2, A4, and A5) belong to the Beijing genotype family, as determined by spoligotyping and region A RFLP. The strain at the bottom of the dendrogram in panel A is the only strain that has an IS6110 RFLP pattern that exhibits >60% similarity to clade 47 patterns and that has spoligo and region A RFLP patterns not characteristic of Beijing strains. The clade 61 isolates (group B3) belong to the Beijing lineage, as determined by spoligotyping and region A RFLP. In addition, six of the strains in the branches neighboring clade 61 are of the Beijing lineage. Note that many of the Beijing isolates in this figure show a false-positive weak hybridization to spacer 28; this was due to the quality of the spoligotype membranes of batch 03052001.

The IS6110 RFLP patterns of one group shared 52.3% similarity to those of clade 47. All 16 strains from this group had spoligo patterns that did not correspond to those of the Beijing family (data not shown). Southern blot hybridization analysis of these strains with the region A probe yielded a single band, confirming that these isolates do not belong to the Beijing lineage.

The IS6110 RFLP patterns of the isolates of the remaining four groups neighboring clade 47 (Fig. 1, groups A1, A2, A4, and A5) shared more than 60% similarity to those of clade 47 (group A3). Among the 19 isolates of these four groups, 18 exhibited Beijing-specific (n = 12) or Beijing-like (n = 6) spoligo patterns (Table 2 and Fig. 1A). Hybridization with the region A probe confirmed that all of the six strains with a Beijing-like spoligo pattern had the A1 IS6110 insertion in the dnaA-dnaN region (Table 1). The final strain examined, from group A5, had an unrelated spoligo pattern consisting of 40 spacers; this strain also did not exhibit a Beijing-characteristic A1 insertion, confirming that it did not belong to the Beijing lineage. The results for this strain suggest that a definition of Beijing family strains based on IS6110 RFLP pattern alone may include strains with a non-Beijing-characteristic spoligo pattern and without the Beijing-characteristic A1 IS6110 insertion. However, if only clade 47 isolates were defined as Beijing family strains, 18 Beijing family strains with similar IS6110 RFLP patterns would be missed. A threshold of >60% similarity to clade 47 in the IS6110 RFLP patterns would include all Beijing family strains and only a single non-Beijing strain.

Does the clade 47 IS6110 RFLP pattern identify all strains of the Beijing lineage?

To determine whether the IS6110 RFLP patterns of strains with a Beijing spoligotype always cluster with those of clade 47 and the closely related Beijing strains identified by highly similar IS6110 RFLP patterns, a representative sample of 845 strains from the Dutch database were spoligotyped. Because changes in spoligotype are less frequent than changes in IS6110 RFLP pattern, strains related on basis of IS6110 RFLP usually have identical or highly related spoligo patterns (9, 19). Spoligotyping of at least two representatives of each clade should, therefore, result in a representative sample of all spoligotype patterns in a genotype family of M. tuberculosis.

Two to 18 randomly selected representatives of each of the 92 clades (n = 294), other than clade 47, as well as 551 isolates not assigned to a clade (Table 1) were spoligotyped. Exclusively strains of clade 61 (n = 8) had a Beijing or Beijing-like spoligo pattern. The spoligotype analysis was extended to all isolates that were closely related to clade 61 (n = 16) (Fig. 1B). These isolates showed at least 47.4% similarity to the IS6110 RFLP patterns of clade 61. Six of these strains had a Beijing or Beijing-like spoligotype. The remaining 10 strains exhibited unrelated spoligo patterns (Fig. 1B and Table 2). All eight members of clade 61 and the six closely related strains with Beijing or Beijing-like spoligo patterns showed the two hybridization bands characteristic of the Beijing lineage when tested with the region A probe. The 10 strains with spoligo patterns other than Beijing type had a non-Beijing-specific region A RFLP pattern.

We concluded that the IS6110 RFLP pattern of clade 47 and closely related strains was not sufficient to identify all strains of the Beijing lineage; a definition based on this RFLP pattern would not have identified members of clade 61.

Recognition of Beijing lineage strains by region A RFLP.

To determine whether IS6110 insertion in the dnaA-dnaN region is a specific marker of the Beijing lineage, 860 strains were subjected to region A probing. These 860 strains were previously typed by IS6110 RFLP and included 510 isolates belonging to 83 different clades (varying from n = 1 to n = 46 per clade) other than clade 47 (n = 56) and clade 61 (n = 8) and 286 isolates not assigned to a clade.

Of these 860 strains, 727 isolates did not have the A1 insertion. To confirm their non-Beijing status, 332 of the 727 isolates were also spoligotyped, and none of them had the Beijing-characteristic spoligotype (Table 2). Furthermore, 37 of the 133 isolates that did have an insertion of IS6110 in the dnaA-dnaN region exhibited region A RFLP patterns consisting of two bands of sizes other than those for Beijing lineage isolates; 10 of these were spoligotyped and showed non-Beijing spoligotypes. Ninety-six isolates exhibited region A RFLP patterns characteristic of Beijing lineage strains (n = 92) or a three-band hybridization pattern, indicating two insertions of IS6110 in the dnaA-dnaN region (n = 4). The latter 4 strains and 78 of the strains with the characteristic A1 insertion exhibited Beijing or Beijing-like spoligo patterns; these were all members of IS6110 RFLP clades 47 and 61 or shared a high similarity to these clades (Table 2). Fourteen strains had two hybridization fragments in region A RFLP analysis that were of similar sizes as Beijing lineage strains, but they did not show Beijing-characteristic spoligotypes. Nine of these 14 strains belonged to seven different clades on the basis of IS6110, other than clades 47 and 61, and the remaining five were isolates not assigned to a clade.

To summarize, region A detected all 82 Beijing lineage strains included in the sample, as determined by IS6110 RFLP analysis and spoligotyping. However, 14 isolates were falsely identified. Therefore, region A probing is not very useful for screening, but it can be used for confirmation if there is doubt about whether an isolate belongs to the Beijing lineage.

Definition of Beijing lineage strains.

Our analysis suggests that spoligotyping is the method of choice for identifying strains of the Beijing lineage. Of the 68 strains with a Beijing spoligo pattern, 64 had the Beijing-specific A1 insertion and 4 had two IS6110 insertions in the origin of replication but were also Beijing strains as determined by IS6110 RFLP analysis. In addition, 14 strains with Beijing-like spoligo patterns also had the characteristic A1 insertion. Furthermore, no clade 47- or 61-related isolates with the A1 insertion and a non-Beijing spoligotype were found.

Therefore, Beijing or Beijing-like spoligotype patterns can serve as the “gold standard” for defining members of the Beijing lineage. On the basis of comparative analysis involving three genetic markers, we define M. tuberculosis Beijing lineage isolates as those isolates showing hybridization to at least three of the spacers 35 to 43 in spoligotyping and showing an absence of hybridization to spacers 1 to 34.

Because many institutes have IS6110 RFLP databases available without information about the respective spoligotypes, a definition based on IS6110 RFLP analysis would facilitate inclusion of many more groups in the worldwide survey. Analysis of the spoligo patterns of 1,020 strains representing the breadth of IS6110 RFLP types in The Netherlands identified two groups of isolates with Beijing or Beijing-like spoligo patterns, clade 47 and clade 61. Furthermore, some of the strains that shared a high similarity to these clades also had a Beijing spoligotype. The diversity in IS6110 RFLP patterns associated with Beijing lineage strains limits the usefulness of this technique as an identification tool. However, a set of IS6110 RFLP patterns could be used to screen databases for Beijing isolates, as detailed below.

Selection of Beijing reference IS6110 RFLP patterns.

In the absence of spoligotyping data, it would be useful to have reference IS6110 RFLP patterns that can be used to search DNA fingerprint databases for the presence of Beijing lineage strains. Therefore, 19 representative reference IS6110 RFLP patterns, including patterns from both clade 47 and clade 61, have been selected for the identification of Beijing genotypes. With a 75% similarity threshold, the selected patterns yielded 100% specificity and sensitivity for finding Beijing lineage isolates (defined by spoligotype) when applied to the Dutch database. The DNA fingerprint patterns of these 19 Beijing reference strains are shown in Fig. 2.

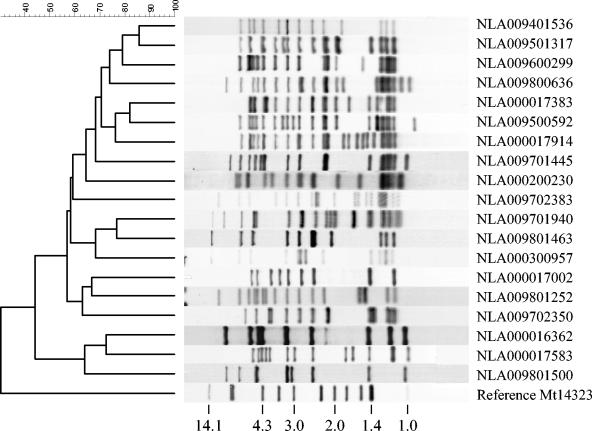

FIG. 2.

IS6110 RFLP patterns of the 19 M. tuberculosis Beijing reference strains and of M. tuberculosis reference strain Mt14323. The molecular sizes of the IS6110-containing PvuII restriction fragments of Mt14323 are shown in kilobases. Two strains are from the PHRI collection and are represented here as NLA000200230 (TN14439N4) and NLA000300957 (TN11265LB).

W lineage isolates.

At the Tuberculosis Center of the PHRI, IS6110 RFLP typing has been used extensively, and many outbreaks caused by W strains were detected. Later it was discovered that on the basis of molecular characteristics, W strains grouped with strains of the Beijing genotype family (21). A total of 2,880 Beijing/W clinical isolates have been identified in a collection of over 17,000 samples maintained at the Tuberculosis Center, PHRI. The Beijing/W grouping was determined by IS6110 RFLP pattern similarity, spoligotyping, the A1 insertion in the origin of replication, and at least one IS6110 insertion in the NTF locus, as previously described (2, 21). The 2,880 Beijing/W isolates had 670 closely related IS6110 RFLP patterns, which share similarity with the IS6110 RFLP patterns of clade 47 identified in the Dutch database. In addition, A1 insertion site mapping analysis and spoligotyping further identified over 900 clinical isolates with 100 different IS6110 RFLP patterns (21). These isolates shared a high degree of similarity with clade 61. This second group of isolates was identified as representatives of ancestral strains of the Beijing/W lineage (25; Bifani et al., unpublished data).

A representative subset (n = 12) of the 2,880 Beijing/W clinical isolates described above, including the most diverse strains, were analyzed at the RIVM. All 12 strains had Beijing spoligotype patterns.

IS6110 RFLP typing of 9 of 12 W lineage isolates revealed that five strains could be assigned to or were closely related to clade 47. One strain (TN8222HD6) belonged to clade 61, and three strains belonged to a group showing 55.7% similarity to clade 61 patterns. Two of the RFLP patterns from the W lineage isolates were included in the 19 Beijing reference patterns. The patterns of the remaining seven W lineage isolates were compared to the Beijing reference patterns and were found to show 80% or more similarity. From this analysis we concluded that the reference set of IS6110 RFLP patterns showed 100% sensitivity for detection Beijing/W strains when a similarity cutoff of 80% was used.

Association between Beijing spoligotype and IS6110 RFLP in the international database.

On basis of spoligotype, 318 (29.3%) of 1,084 strains in the international database were of the Beijing lineage. The countries of origin of these isolates and the number of isolates per country are listed in Table 3. From the same database we also identified 314 strains with IS6110 RFLP patterns matching the 19 Beijing reference patterns described above (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

IS6110 RFLP and spoligo patterns of M. tuberculosis strains in the international database

| Country of isolation | No. of isolates with the indicated genotype, determined by:

|

Total no. of isolates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spoligo pattern

|

RFLP pattern

|

|||||

| Beijing | Beijing-like | Other | Beijing | Other | ||

| Africa | 12 | 12 | 12 | |||

| Argentinaa | 60 | 60 | 60 | |||

| Aserbaijan | 46 | 17 | 46 | 17 | 63 | |

| Austria | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Belgium | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Bolivia | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Chili | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Chinaa | 34 | 6 | 34 | 6 | 40 | |

| Cubaa | 22 | 1 | 157 | 25 | 155 | 180 |

| Curacao | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Czech Republic | 4 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Equador | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Ethiopia | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Germany | 17 | 17 | 17 | |||

| Honduras | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Hong Konga | 49 | 2 | 18 | 50 | 19 | 69 |

| Indiaa | 6 | 133 | 5 | 134 | 139 | |

| Indonesiaa | 25 | 1 | 55 | 26 | 55 | 81 |

| Irana | 6 | 64 | 6 | 64 | 70 | |

| Irelanda | 25 | 25 | 25 | |||

| Japan | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Malaysia | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Mexico | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||

| Mongoliaa | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 20 | |

| Philippinesa | 1 | 39 | 1 | 39 | 40 | |

| Poland | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Russia | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 5 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 6 | 6 | 6 | |||

| Somalia | 7 | 7 | 7 | |||

| South Africa | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| South Korea | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Spain | 7 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Switzerland | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Tahiti | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Thailand | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| United Kingdoma | 27 | 27 | 27 | |||

| United States | 9 | 2 | 5 | 11 | 5 | 16 |

| Venezuela | 18 | 18 | 18 | |||

| Vietnama | 93 | 2 | 46 | 91 | 50 | 141 |

| Total | 309 | 9 | 766 | 314 | 770 | 1,084 |

The isolates from this country represented a nonbiased sample, i.e., from whole population studies, consecutively diagnosed patients, or random samples.

Comparison of the strains identified by spoligotyping and IS6110 RFLP showed eight isolates with contradictory results. Two isolates originating from Cuba were Beijing on the basis of IS6110 RFLP but exhibited spoligo patterns not characteristic of Beijing strains. These isolates showed 77.4 and 78.1% similarity, respectively, to one of the Beijing reference strains. Six strains from Hong Kong (n = 1), India (n = 1), and Vietnam (n = 4) were detected by spoligotyping only. The RFLP pattern similarities of these six strains to the Beijing reference patterns varied from 65 to 73%. The sensitivity of searching the international database for Beijing family strains on basis of IS6110 RFLP pattern on the basis of ≥75% matching of the 19 Beijing reference strains was 98.1% (312 of 318), and the specificity was 99.7% (764 of 766).

Investigation of a German database with the Beijing reference IS6110 RFLP patterns.

In addition to searches of the Dutch and international databases, both of which are maintained at the RIVM, the 19 Beijing reference IS6110 RFLP patterns were used to search a German database of 452 IS6110 RFLP patterns from a collection of multidrug-resistant isolates. One hundred eighty-eight Beijing-like IS6110 RFLP patterns were identified in the German database by using a 75% similarity cutoff. All 188 strains were subjected to spoligotyping, and only one of them did not have a Beijing-characteristic spoligotype. The IS6110 RFLP pattern of this strain showed 83% similarity to one of the reference patterns. As a control, we also spoligotyped 72 isolates from the years 2000 and 2001 that showed less than 75% similarity to the reference IS6110 RFLP patterns. None of these strains had a Beijing-characteristic spoligotype. We concluded that the specificity of matching with the IS6110 reference patterns was at least 98.6% (72 of 73) and that the sensitivity was 100% (187 of 187).

Investigation of the Danish database with the Beijing reference IS6110 RFLP patterns.

The Danish database comprised 3,936 IS6110 RFLP patterns from a population-based study covering the period from 1992 to 2002. By using the 19 reference IS6110 RFLP patterns, 126 putative Beijing strains were identified. All 126 strains were spoligotyped, and 30 of these strains showed non-Beijing spoligo patterns. Another 82 strains were randomly selected and spoligotyped. These strains all contained five or more IS6110 elements and exhibited diverse IS6110 RFLP patterns. No Beijing-like spoligotype patterns were identified among these control strains. The sensitivity of matching with the Beijing reference strains was therefore 100%. The specificity, using a 75% cutoff, was 73.2% (82 of 112). Using a 80% cutoff, the specificity increased to 96.4% (108 of 112), but the sensitivity decreased to 91.7% (88 of 96).

DISCUSSION

The Beijing strains represent the largest genotype family of M. tuberculosis recognized so far; this genetically closely related group of strains represents more than 11% of all 11,708 clustered spoligo patterns analyzed from worldwide databases (11). Furthermore, strains of this genotype are globally distributed: in East Asia, 50% of the isolates are of the Beijing lineage; in North America, Oceania, and Europe, 16, 13, and 4% of the isolates, respectively, are of the Beijing lineage (11). In contrast to other groups of M. tuberculosis isolates, strains of the Beijing family exhibit a remarkable constant spoligotype and high degrees of similarity among IS6110 RFLP, polymorphic GC-rich sequence RFLP, and variable numbers of tandem repeats profiles (19). The similarity of these highly polymorphic markers is indicative of a very recent common ancestor for the Beijing family strains. The rapid global spread and clonal expansion of Beijing strains may be related to selective advantages such as enhanced resistance to BCG vaccination or to treatment with antituberculosis drugs. We have undertaken this study in order to define the molecular characteristics of strains of the Beijing lineage. A clear and standard definition will aid the identification of these strains and the phenotypic traits explaining the successful spread of this family of M. tuberculosis strains.

In this study, the utility of spoligotyping, IS6110 RFLP analysis, and insertion of IS6110 in the dnaA-dnaN region to recognize M. tuberculosis Beijing lineage strains was determined. On the basis of IS6110 RFLP, Beijing lineage isolates were divided into two different groups, i.e., one group (clade 47-related strains) with multibanded RFLP patterns similar to those of the Beijing family (37) and the W family (4) and a second group (clade 61-related isolates) with distantly related IS6110 RFLP profiles. In two other studies the latter group of strains has also been determined to belong to the Beijing/W lineage by use of other molecular markers and has been found to represent ancestral isolates (25; Bifani et al., unpublished data). Both groups of strains form part of the Beijing/W lineage and can also be distinguished by the composition of their NTF region (2, 21, 27). Ancestral Beijing strains (clade 61 and related strains) do not contain a copy of IS6110 in this region, and modern Beijing strains (Beijing family and W strains, clade 47 and related strains) contain at least one copy of IS6110 in this region. It will be interesting to know whether isolates of these different groups exhibit the same characteristics regarding their ability to spread and gain resistance. In northwestern Russia, 96% of the Beijing strains represent the modern Beijing family, and most of these strains were multidrug resistant (25).

Spoligotyping proved the most useful method to recognize Beijing lineage strains: it is the most rapid and easiest method to apply, and it correlates well with the other methods. However, similar to the case for the A1 insertion, it cannot differentiate modern from ancestral Beijing strains. Besides the characteristic nine-spacer spoligo pattern, consisting of spacers 35 to 43, Beijing lineage strains sometimes exhibit a subset of these spacers. Such Beijing-like spoligo patterns were observed among M. tuberculosis isolates from China (37), Cuba (7), Denmark (1% [1 of 96]) (this study), Germany (1.1% [2 of 187]) (this study), Hong Kong (5), Indonesia (29), The Netherlands (8.9% [14 of 156]) (this study), South Korea, the United States (2), and Vietnam (unpublished data). We confirmed that these Beijing-like spoligo patterns represent true members of the Beijing lineage by IS6110 RFLP and the presence of a copy of IS6110 in the origin of replication. Mokrousov and colleagues found that in some Beijing strains polymorphism detected by spoligotyping does not necessarily imply that spacers are absent (24). They investigated this by performing PCRs with different primer combinations, using one primer directed to the IS6110 insertion sequence and one directed to the direct repeat, followed by spoligotyping of these PCR products. It was found that in two epidemiologically unrelated Beijing strains, asymmetrical insertion of IS6110 in the direct repeat between spacers 36 and 37 prevented spacer 37 from being amplified in PCR, which led to absence of hybridization in regular spoligotyping. Using the same technique, they found that in two Beijing strains lacking hybridization to spacer oligonucleotides 37 and 38 and one Beijing strain lacking hybridization to spacer oligonucleotide 40, the respective spacers were truly absent (24). Previously, in another prevalent M. tuberculosis genotype, the Haarlem family, spacer 31 was not detected by spoligotyping due to the asymmetrical insertion of an extra IS6110 copy between spacers 31 and 32 (12, 22). It should be noted that the direct repeat region constitutes a preferential IS6110 insertion site (16, 22), and an absence of hybridizing spacers may therefore not always reflect a lack of spacers in the direct repeat region of the respective bacteria. Therefore, care should be taken regarding the interpretation of missing spacers in spoligo patterns.

In this study, M. tuberculosis Beijing lineage strains were defined as strains hybridizing to at least three of the nine spacers 35 to 43 and with an absence of hybridization to spacers 1 to 34. Worldwide, there are many more IS6110 RFLP patterns available than spoligo patterns, which emphasizes the need for an additional definition based on this marker. For this purpose a set of 19 representative IS6110 RFLP patterns of Beijing strains was selected. It was demonstrated that these IS6110 RFLP patterns had a very high sensitivity and specificity for identifying Beijing lineage strains, including the Beijing family and the ancestral strains, in an international data set consisting of 1,084 isolates. Furthermore, these patterns were useful for identifying Beijing lineage strains in large databases in two other European countries, comprising in total 4,554 IS6110 RFLP patterns. We recommend that these 19 Beijing reference patterns be used when Beijing lineage strains need to be defined in IS6110 RFLP pattern collections. Matching results should be interpreted by the actual similarities to each of the individual 19 strains and not by preparation of a dendrogram. As determined in this study, strains that have patterns matching more than 80% to any of these patterns should be classified as Beijing. Strains that match with a similarity of between 75 and 80% should, in addition, be subjected to spoligotyping or region A RFLP for confirmation.

No definition of the Beijing genotype on the basis of genetic markers will be 100% perfect, because there will always be exceptional strains. Exceptions on the basis of spoligotyping are expected to be very rare. In the Dutch data set, no strains with Beijing-characteristic RFLP and region A patterns but non-Beijing spoligotypes were found. Exceptions on the basis of IS6110 RFLP will occur more frequently, since the half-life of IS6110 RFLP is estimated to be approximately 3.5 years (6), and errors in processing and interpretation are more likely. Furthermore, in some geographical areas that were not included in this study, lineages of the Beijing genotype may have developed that are evolutionarily more diverged than the Beijing strains studied so far.

The definition of Beijing strains has been developed to minimize inaccuracies and to allow a standardized approach to study the spread of these strains and their association with, for example, drug resistance and patient ages in more detail (13). Within the framework of a European Union project, a worldwide survey using this definition is already in progress. The current worldwide tuberculosis epidemic seems to be strongly influenced by the spread of several particular M. tuberculosis genotype families, such as the Beijing family, the Latino-American and Mediterranean family, the Haarlem family, the X clade, and other major, less defined clades (11). In general, the genetic polymorphism among M. tuberculosis isolates observed in high-incidence areas is low in comparison to that in countries with a low incidence of tuberculosis (32). In low-incidence countries, immigration and reactivation of remote infections influence the genetic diversity of M. tuberculosis isolates. The high prevalence of conserved genotypes in high-incidence areas suggests selective advantages of these prevalent genotypes. The success of these strains could originate from increased transmissibility or from different gene expression of as-yet-unidentified virulence factors (2). In this respect a more developed mechanism to circumvent the BCG-induced immunity and a higher ability to gain resistance against antituberculosis drugs have been hypothesized (1, 37). Molecular characterization of M. tuberculosis genotypes will facilitate future studies on the spread of these genotypes and their influence on the tuberculosis epidemic. This will be the basis for studies on pathogenicity and virulence factors.

Acknowledgments

This study was carried out within the framework of Concerted Action project “Next Generation Genetic Markers and Techniques To Study the Epidemiology and Control of Tuberculosis,” supported by the European Union under grant QLK2-CT-2000-00630. J. R. Glynn was supported by DFID, United Kingdom, and is currently supported by the Department of Health, United Kingdom. The Danish Lung Association supported T. Lillebaek.

All collaborators who have contributed to the DNA fingerprint databases are gratefully acknowledged. Jarg van Asch, Annemarie van den Brandt, Mirjam Dessens, Mimount Enaimi, Petra de Haas, Tridia van der Laan, and Rachida Siamari are acknowledged for their excellent technical assistance. Tanja Kubica is acknowledged for her work on the German database. Noel Smith is acknowledged for helpful comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anh, D. D., M. W. Borgdorff, L. N. Van, N. T. N. Lan, T. van Gorkom, K. Kremer, and D. van Soolingen. 2000. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype emerging in Vietnam. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 6:302-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bifani, P. J., B. Mathema, N. E. Kurepina, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 2002. Global dissemination of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis W-Beijing family strains. Trends Microbiol. 10:45-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bifani, P. J., B. Mathema, Z. Liu, S. L. Moghazeh, B. Shopsin, B. Tempalski, J. Driscol, R. Frothingham, J. M. Musser, P. Alcabes, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 1999. Identification of a W variant outbreak of Mycobacterium tuberculosis via population-based molecular epidemiology. JAMA 282:2321-2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bifani, P. J., B. B. Plikaytis, V. Kapur, K. Stockbauer, X. Pan, M. L. Lutfey, S. L. Moghazeh, W. Eisner, T. M. Daniel, M. H. Kaplan, J. T. Crawford, J. M. Musser, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 1996. Origin and interstate spread of a New York City multidrug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis clone family. JAMA 275:452-457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan, M. Y., M. W. Borgdorff, C. W. Yip, P. E. W. de Haas, W. S. Wong, K. M. Kam, and D. van Soolingen. 2001. Seventy percent of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Hong Kong represent the Beijing genotype. Epidemiol. Infect. 127:169-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Boer, A. S., M. W. Borgdorff, P. E. de Haas, N. J. Nagelkerke, J. D. van Embden, and D. van Soolingen. 1999. Analysis of rate of change of IS6110 RFLP patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on serial patient isolates. J. Infect. Dis. 180:1238-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diaz, R., K. Kremer, P. E. de Haas, R. I. Gomez, A. Marrero, J. A. Valdivia, J. D. van Embden, and D. van Soolingen. 1998. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in Cuba outside of Havana, July 1994-June 1995: utility of spoligotyping versus IS6110 restriction fragment length polymorphism. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2:743-750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doroudchi, M., K. Kremer, E. A. Basiri, M. R. Kadivar, D. van Soolingen, and A. A. Ghaderi. 2000. IS6110-RFLP and spoligotyping of Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates in Iran. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 32:663-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas, J. T., L. S. Qian, J. C. Montoya, J. M. Musser, J. D. A. Van Embden, D. van Soolingen, and K. Kremer. 2003. Characterization of the Manila family of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:2723-2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enarson, D. A., and J. Chretien. 1999. Epidemiology of respiratory infectious diseases. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 5:128-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filliol, I., J. R. Driscoll, D. van Soolingen, B. N. Kreiswirth, K. Kremer, G. Valetudie, D. D. Anh, R. Barlow, D. Banerjee, P. J. Bifani, K. Brudey, A. Cataldi, R. C. Cooksey, D. V. Cousins, J. W. Dale, O. A. Dellagostin, F. Drobniewski, G. Engelmann, S. Ferdinand, D. Gascoyne-Binzi, M. Gordon, M. C. Gutierrez, W. H. Haas, H. Heersma, G. Kallenius, E. Kassa-Kelembho, T. Koivula, H. M. Ly, A. Makristathis, C. Mammina, G. Martin, P. Mostrom, I. Mokrousov, V. Narbonne, O. Narvskaya, A. Nastasi, S. N. Niobe-Eyangoh, J. W. Pape, V. Rasolofo-Razanamparany, M. Ridell, M. L. Rossetti, F. Stauffer, P. N. Suffys, H. Takiff, J. Texier-Maugein, V. Vincent, J. H. De Waard, C. Sola, and N. Rastogi. 2002. Global distribution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis spoligotypes. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:1347-1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Filliol, I., C. Sola, and N. Rastogi. 2000. Detection of a previously unamplified spacer within the DR locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: epidemiological implications. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1231-1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glynn, J. R., J. Whiteley, P. J. Bifani, K. Kremer, and D. van Soolingen. 2002. Worldwide occurrence of Beijing/W strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: a systematic review. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:843-849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heersma, H. F., K. Kremer, and J. D. van Embden. 1998. Computer analysis of IS6110 RFLP patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods Mol. Biol. 101:395-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hermans, P. W., F. Messadi, H. Guebrexabher, D. van Soolingen, P. E. W. de Haas, H. Heersma, H. de Neeling, A. Youb, F. Portaels, D. Rommel, M. Zribi, and J. D. A. van Embden. 1995. Analysis of the population structure of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Ethiopia, Tunisia, and The Netherlands: usefulness of DNA typing for global tuberculosis epidemiology. J. Infect. Dis. 171:1504-1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hermans, P. W., D. van Soolingen, E. M. Bik, P. E. de Haas, J. W. Dale, and J. D. van Embden. 1991. Insertion element IS987 from Mycobacterium bovis BCG is located in a hot-spot integration region for insertion elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains. Infect. Immun. 59:2695-2705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iseman, M. D. 2000. Tuberculosis—still the #1 killer in infectious diseases. Int. J. Clin. Pract. Suppl. 155:78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamerbeek, J., L. Schouls, A. Kolk, M. van Agterveld, D. van Soolingen, S. Kuijper, A. Bunschoten, H. Molhuizen, R. Shaw, M. Goyal, and J. Van Embden. 1997. Simultaneous detection and strain differentiation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis for diagnosis and epidemiology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:907-914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kremer, K., D. van Soolingen, R. Frothingham, W. H. Haas, P. W. Hermans, C. Martin, P. Palittapongarnpim, B. B. Plikaytis, L. W. Riley, M. A. Yakrus, J. M. Musser, and J. D. van Embden. 1999. Comparison of methods based on different molecular epidemiological markers for typing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: interlaboratory study of discriminatory power and reproducibility. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2607-2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kruuner, A., S. E. Hoffner, H. Sillastu, M. Danilovits, K. Levina, S. B. Svenson, S. Ghebremichael, T. Koivula, and G. Kallenius. 2001. Spread of drug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis in Estonia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3339-3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurepina, N. E., S. Sreevatsan, B. B. Plikaytis, P. J. Bifani, N. D. Connell, R. J. Donnelly, D. van Soolingen, J. M. Musser, and B. N. Kreiswirth. 1998. Characterization of the phylogenic distribution and chromosomal insertion sites of five IS6110 elements in Mycobacterium tuberculosis: non-random integration in the dnaA-dnaN region. Tuber. Lung Dis. 79:31-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legrand, E., I. Filliol, C. Sola, and N. Rastogi. 2001. Use of spoligotyping to study the evolution of the direct repeat locus by IS6110 transposition in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1595-1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez, B., D. Aguilar, H. Orozco, M. Burger, C. Espitia, V. Ritacco, L. Barrera, K. Kremer, P. R. Hernandez, K. Huygen, and D. van Soolingen. 2003. A marked difference in pathogenesis and immune response induced by different Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotypes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 133:30-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mokrousov, I., O. Narvskaya, E. Limeschenko, T. Otten, and B. Vyshnevskiy. 2002. Novel IS6110 insertion sites in the direct repeat locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis clinical strains from the St. Petersburg area of Russia and evolutionary and epidemiological considerations. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1504-1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mokrousov, I., O. Narvskaya, T. Otten, A. Vyazovaya, E. Limeschenko, L. Steklova, and B. Vyshnevskyi. 2002. Phylogenetic reconstruction within Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype in northwestern Russia. Res. Microbiol. 153:629-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfyffer, G. E., A. Strassle, T. van Gorkum, F. Portaels, L. Rigouts, C. Mathieu, F. Mirzoyev, H. Traore, and J. D. A. Van Embden. 2001. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in prison inmates, Azerbaijan. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:855-861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plikaytis, B. B., J. L. Marden, J. T. Crawford, C. L. Woodley, W. R. Butler, and T. M. Shinnick. 1994. Multiplex PCR assay specific for the multidrug-resistant strain W of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1542-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rad, M. E., P. Bifani, C. Martin, K. Kremer, S. Samper, J. Rauzier, B. Kreiswirth, J. Blazquez, M. Jouan, D. van Soolingen, and B. Gicquel. 2003. Mutations in putative mutator genes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains of the W-Beijing family. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 9:838-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Crevel, R., R. H. H. Nelwal, W. de Lenne, Y. Veeraragu, A. G. van der Zanden, Z. Amin, J. W. M. van der Meer, and D. van Soolingen. 2002. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Beijing genotype strains associated with febrile response to treatment. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:880-883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Embden, J. D., M. D. Cave, J. T. Crawford, J. W. Dale, K. D. Eisenach, B. Gicquel, P. Hermans, C. Martin, R. McAdam, T. M. Shinnick, and P. Small. 1993. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:406-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Embden, J. D., T. van Gorkom, K. Kremer, R. Jansen, B. A. Der-Zeijst, and L. M. Schouls. 2000. Genetic variation and evolutionary origin of the direct repeat locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 182:2393-2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Soolingen, D. 2001. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infections: main methodologies and achievements. J. Intern. Med. 249:1-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Soolingen, D., M. W. Borgdorff, P. E. de Haas, M. M. Sebek, J. Veen, M. Dessens, K. Kremer, and J. D. van Embden. 1999. Molecular epidemiology of tuberculosis in The Netherlands: a nationwide study from 1993 through 1997. J. Infect. Dis. 180:726-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Soolingen, D., P. E. de Haas, P. W. Hermans, and J. D. van Embden. 1994. DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods Enzymol. 235:196-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Soolingen, D., P. E. W. de Haas, and K. Kremer. 2001. Restriction fragment length polymorphism typing of mycobacteria, p. 165-203. In T. Parisch and N. G. Stoker (ed.), Mycobacterium tuberculosis protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, N.J. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.van Soolingen, D., P. W. Hermans, P. E. de Haas, D. R. Soll, and J. D. van Embden. 1991. Occurrence and stability of insertion sequences in Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex strains: evaluation of an insertion sequence-dependent DNA polymorphism as a tool in the epidemiology of tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2578-2586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Soolingen, D., L. Qian, P. E. de Haas, J. T. Douglas, H. Traore, F. Portaels, H. Z. Qing, D. Enkhsaikan, P. Nymadawa, and J. D. van Embden. 1995. Predominance of a single genotype of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in countries of east Asia. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:3234-3238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]