Abstract

The genus Corynebacterium is a heterogeneous group of species comprising human and animal pathogens and environmental bacteria. It is defined on the basis of several phenotypic characters and the results of DNA-DNA relatedness and, more recently, 16S rRNA gene sequencing. However, the 16S rRNA gene is not polymorphic enough to ensure reliable phylogenetic studies and needs to be completely sequenced for accurate identification. The almost complete rpoB sequences of 56 Corynebacterium species were determined by both PCR and genome walking methods. In all cases the percent similarities between different species were lower than those observed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing, even for those species with degrees of high similarity. Several clusters supported by high bootstrap values were identified. In order to propose a method for strain identification which does not require sequencing of the complete rpoB sequence (approximately 3,500 bp), we identified an area with a high degree of polymorphism, bordered by conserved sequences that can be used as universal primers for PCR amplification and sequencing. The sequence of this fragment (434 to 452 bp) allows accurate species identification and may be used in the future for routine sequence-based identification of Corynebacterium species.

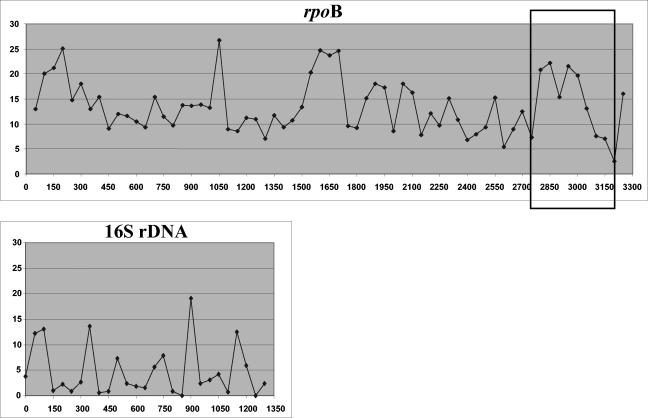

The genus Corynebacterium is one of the largest genera in the coryneform group of bacteria (which consist of irregular gram-positive rods and aerobically growing, asporogenous, non-partially acid-fast bacteria). Originally, the genus Corynebacterium was created essentially to accommodate the diphtheria bacillus and some other species pathogenic for animals. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology listed only 17 Corynebacterium species; however, 11 new species were defined between 1987 and 1995 (6), and another 32 new species were described between 1996 and 2003. From 2001 to 2003, up to 13 new species were validly published (http://www.bacterio.cict.fr/c/corynebacterium.html). At present, the genus Corynebacterium contains more than 60 species, the vast majority of which have been isolated from human or animal samples. Chemotaxonomically, this genus includes species that possess wall chemotype IV (arabinose, galactose and meso-diaminopimelic acid), short-chain mycolic acids (approximately 22 to 36 carbon atoms), and DNA G+C contents ranging from 51 to 63 mol% (5, 6). The narrower definition of the genus Corynebacterium has resulted in the transfer of several species (Clavibacter, Rhodococcus, and Turicella) to other genera. However, there is still some evidence of heterogeneity within the genus Corynebacterium. For example, Corynebacterium amycolatum and Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii lack mycolic acids (1, 2), Corynebacterium afermentans and Corynebacterium auris exhibit G+C contents of more than 65 mol% (6). The use of molecular genetic methods such as 16S rRNA gene (rDNA) sequence analysis has facilitated a much tighter circumscription of the genus, and the availability of comparative 16S rRNA gene sequence data with improved phenotypic data has resulted in much improved and more reliable species identification (14, 16). These improvements in taxonomy and means of detection, together with an increased interest in Corynebacterium as an opportunistic infectious agent in humans, have resulted in the delineation of a plethora of new Corynebacterium species from human sources in recent years (6, 8). However, the identification of Corynebacterium species is difficult because it often requires fastidious procedures, such as chromatography, or a high number of tests that are not available with commercial identification systems (5). The sequence of the 16S rRNA gene is the most widely used molecular marker to determine the phylogenetic relationships of bacteria. However, low intragenus polymorphism limits its usefulness for taxonomic analysis or identification to the species level. As an example, the species Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum and Corynebacterium propinquum and the species Corynebacterium minutissimum and Corynebacterium aurimucosum have high 16S rDNA similarity values (99.3 and 98.7%, respectively). Moreover, from the perspective of automated systems for gene sequence based-identification, this low degree of polymorphism obligates sequencing of the complete 16S rRNA gene (approximately 1,500 bp) for accurate identification. Variable areas are spotted along the gene at positions 0 to 150, 300 to 400, 650 to 800, 850 to 950, and 1100 to 1250 (a total of 650 bp), with maximal variability ranging from 8 to 19% according to the region (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Graphical representation of RSVs (y axis) in the rpoB and 16S rRNA gene sequences of Corynebacterium species studied by the use of windows of 50 nucleotides (the x axis indicates the nucleotide position). The hypervariable region bordered by conserved regions used for species identification with primers C2700F and C3130R is framed.

Among the universal genes that can be used for taxonomic analysis and gene sequence-based identification, the RNA polymerase beta subunit-encoding gene (rpoB) was used to study several unrelated genera, including Bartonella spp. (15), Staphylococcus spp. (3), members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (13), Bosea spp. and Afipia spp. (9), Mycobacterium spp. (10), and Legionella spp. (11). In the study described here, we investigated the usefulness of rpoB sequencing for the differentiation and identification of 56 Corynebacterium species and 2 related species, Rhodococcus equi and Turicella otitidis. As rpoB is a large gene (approximately 3,500 bp), we also determined regions of variability in the sequence bordered by conserved sequences with the objective of designing universal primers for amplification of a small but discriminative sequence for use in the routine identification of Corynebacterium species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The bacterial stains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Most strains were obtained from the Collection de l'Institut Pasteur (CIP) and from the Culture Collection of the University of Göteborg, Göteborg, Sweden (CCUG). All strains were cultured on Columbia agar plates with 5% sheep blood (Trypticase soy agar; bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Etoile, France) and were incubated for 24 to 72 h at 30 to 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere.

TABLE 1.

Species for which rpoB sequences were determined, including GenBank access numbers and sizes of the sequences determined

| Species | Strain | Genbank accession no.

|

Size (bp) of rpoB sequence determined

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA gene | rpoB gene | Complete | Partial | ||

| Corynebacterium accolens | CIP 104783T | AJ439346 | AY492242 | 3,282 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium afermentans subsp. afermentans | CIP 103499T | X82054 | AY492265 | 3,347 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium afermentans subsp. lipophilum | CIP 103500T | X82055 | AY492266 | 3,178 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium ammoniagenes | CIP 101283T | X82056 | AY492243 | 3,349 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium amycolatum | CIP 103452T | X82057 | AY492241 | 3,435 | 434 |

| Corynebacterium argentoratense | CIP 104296T | X83955 | AY492249 | 3,349 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium aurimucosum | CCUG 47449T | AJ309207 | AY492282 | 3,330 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium auris | CIP 104632T | X81873 | AY492234 | 3,357 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium auriscanis | CIP 106629T | AJ243820 | AY492244 | 3,346 | 452 |

| Corynebacterium bovis | CIP 5480T | X82051 | AY492236 | 3,450 | 452 |

| Corynebacterium callunae | CIP 104277T | X82053 | AY492245 | 3,340 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium camporealensis | CIP 105508T | Y09569 | AY492246 | 3,340 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium capitovis | CIP 106739T | AJ297402 | AY492247 | 3,350 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium confusum | CIP 105403T | Y15886 | AY492248 | 3,356 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium coyleae | CIP 104919T | X96497 | AY492250 | 3,314 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium cystitidis | CIP 103424T | X82058 | AY492251 | 3,340 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium diphtheriae | CIP 100721T | X82059 | AY492230 | 3,477 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium durum | CIP 105490T | Z97069 | AY492252 | 3,340 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium efficiens | YS-314 | AB055963 | AP005215 | 3,480 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium falsenii | CIP 105466T | Y13024 | AY492253 | 3,330 | 452 |

| Corynebacterium felinum | CIP 106740T | AJ401282 | AY492254 | 3,334 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium flavescens | CIP 69.5T | X82060 | AY492255 | 3,303 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium freneyi | CIP 106767T | AJ292762 | AY492237 | 3,345 | 434 |

| Corynebacterium glucuronolyticum | CIP 104577T | X86688 | AY492256 | 3,328 | 434 |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum | ATCC 13032 | X80629 | NC_003450 | 3,480 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium imitans | CIP 105130T | Y09044 | AY492259 | 3,333 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium jeikeium | CIP 103337T | X82062 | AY492231 | 3,463 | 452 |

| Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii | CIP 105744T | Y10077 | AY492274 | 3,349 | 452 |

| Corynebacterium kutscheri | CIP 103423T | X82063 | AY492257 | 3,168 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium lipophiloflavum | CIP 105127T | Y09045 | AY492260 | 3,340 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium macginleyi | CIP 104099T | X80499 | AY492276 | 3,173 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium mastitidis | CIP 105509T | Y09806 | AY492281 | 3,174 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium matruchotii | CIP 81.82T | X82065 | AY492238 | 3,338 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium minutissimum | CIP 100652T | X84679 | AY492235 | 3,358 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium mucifaciens | CIP 105129T | Y11200 | AY492261 | 3,330 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium mycetoides | CIP 55.51T | X82066 | AY492262 | 3,332 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium phocae | CIP 105741T | Y10076 | AY492277 | 3,180 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium pilosum | CIP 103422T | X84246 | AY492258 | 3,296 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium propinquum | CIP 103792T | X81917 | AY492279 | 3,179 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium pseudodiphtheriticum | CIP 103420T | X81918 | AY492232 | 3,477 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis | CIP 102968T | X81916 | AY492239 | 3,447 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium renale | CIP 103421T | X81909 | AY492240 | 3,442 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium riegelii | CIP 105310T | Y14651 | AY492278 | 3,180 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium seminale | CIP 104297T | X84375 | AY492263 | 3,153 | 434 |

| Corynebacterium simulans | CIP 106488T | AJ012837 | AY492264 | 3,176 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium singulare | CIP 105491T | Y10999 | AY492280 | 3,180 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium spheniscorum | CCUG 45512T | AJ429234 | AY492283 | 3,283 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium striatum | CIP 81.15T | X81910 | AY492267 | 3,346 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium sundsvallense | CIP 105936T | Y09655 | AY492268 | 3,359 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium terpenotabidum | CIP 105927T | AB004730 | AY492269 | 3,286 | 452 |

| Corynebacterium testudinoris | CCUG 41823T | AJ295841 | AY492284 | 3,320 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium thomssenii | CIP 105597T | AF010474 | AY492270 | 3,352 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium ulcerans | CIP 106504T | X81911 | AY492271 | 3,176 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium urealyticum | CIP 103524T | X81913 | AY492275 | 3,172 | 452 |

| Corynebacterium variabile | CIP 102112T | AJ222815 | AY492272 | 3,343 | 452 |

| Corynebacterium vitaeruminis | CIP 827T | X84680 | AY492273 | 3,296 | 446 |

| Corynebacterium xerosis | CIP 100653T | X81914 | AY492233 | 3,447 | 434 |

| Turicella otitidis | CIP 104075T | X73976 | AY492287 | 3,250 | 446 |

| Rhodococcus equi (formerly Corynebacterium hoagii) | CIP 81.17T | X82052 | AY492285 | 3,357 | 449 |

| Rhodococcus equi | CIP 5472T | AF490539 | AY492286 | 3320 | 449 |

rpoB gene amplification and sequencing.

The sequence of the rpoB gene from Corynebacterium species and species most closely related to Corynebacterium species were aligned in order to produce a consensus sequence. The bacteria chosen were Corynebacterium glutamicum, Amycolatopsis mediterranei, and Mycobacterium smegmatis (GenBank accession numbers NC_003450, AF242549, and MSU24494, respectively). The consensus sequence was used to generate primers that were used in PCRs, for genome walking (17), and for sequencing. Additional primers were selected from ongoing base sequence determinations. All primers used in this study are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used for amplification and sequencing of the rpoB gene in this study

| Primer name | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Positiona | Tmb (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C240F | GGAAGGAYGCATCTTGGCAGTCT | −13 | 68 |

| C150F | GGYACGCCYGAGTGGC | 133 | 56 |

| C35F | GGAAGGACCCATCTTGGCAGT | −13 | 66 |

| C41F | CAGTCTCCCGCCAGACCA | 5 | 60 |

| C445R | CATYGGGAARTCRCCGATGA | 401 | 60 |

| C40F | CAGTCTCCCGCCAGACCAA | 5 | 62 |

| C390F | ATCAAGTCYCAGACKGTYTTCATC | 322 | 68 |

| C390R | GATGAARACMGTCTGRGACTTGAT | 322 | 68 |

| C630F | GACCGCAAGCGYCGCCAG | 621 | 64 |

| C600f | TGGYTBGARTTYGACGT | 574 | 50 |

| C600r | ACGTCRAAYTCVARCCA | 574 | 50 |

| C640R | GGCTGRCGRCGCTTGCGGT | 623 | 66 |

| C890F | TACAAGRTCAACCGCAAG | 883 | 52 |

| C820R | GGRCGYTGCTTGCGGTAGA | 772 | 62 |

| C1050F | CGAYGACATYGACCACTT | 1040 | 54 |

| C1050R | GGTTRCCRAAGTGGTCRATGTC | 1045 | 68 |

| C1295F | CAGTTYMTGGACCAGAACAAC | 1254 | 62 |

| C1410F | GAGCGYATGACCACBCAGGA | 1144 | 64 |

| C1410R | TCCTGVGTGGTCATRCGCTC | 1144 | 64 |

| C1415F | CBCACTACGGMCGYATGTG | 1373 | 62 |

| C1740F | ACGATGCTAACCGTGCACTGAT | 1739 | 66 |

| C1740R | CCCATCAGTGCACGGTTAGCAT | 1742 | 68 |

| C1765R | GTGCTCSAGGAAYGGRATCA | 1718 | 62 |

| C1770F | TGATGGGYGCSAACATGCAG | 1757 | 64 |

| C1800f | ATGGGYGCSAACATGCAG | 1759 | 56 |

| C1800r | CTGCATGTTSGCRCCCAT | 1759 | 56 |

| C2160R | GRCCYTCCCAHGGCATGAA | 2107 | 60 |

| C2130F | GGARGGCCACAACTACGAGGA | 2118 | 64 |

| C2130R | GTGGCCYTCCCAHGGCATGAA | 2107 | 68 |

| C2350F | ACATCCTGGTCGGTAAGGTCAC | 2339 | 68 |

| C2350R | GTGACCTTACCGACCAGGATGT | 2339 | 68 |

| C2385F | CATCCTSGTSGGYAAGGTCA | 2340 | 64 |

| C2410R | ATGATCGCRTCCTCGTAGTTGTG | 2125 | 68 |

| C2410F | CACAACTACGAGGAYGCGATCAT | 2125 | 68 |

| C2470R | CGATCTCGTGCTCCTCGATGT | 2192 | 66 |

| C2590F | CARAAGCGCAAGATCCARGA | 2563 | 60 |

| C2625F | AGATCCARGAYGGCGAYAAG | 2572 | 60 |

| C3190F | ATGGAGGTGTGGGCAATGCAG | 3154 | 66 |

| C3190R | CTGCATTGCCCACACCTCCAT | 3154 | 66 |

| C3200r | CTGCATBGCCCACACCTCCAT | 3154 | 68 |

| C3215R | GCCTGCATBGCCCACACCT | 3158 | 64 |

| C3300F | GAAGGGCGADAAYATYCCGGAT | 3264 | 66 |

| C3300R | TCCGGRATRTTHTCGCCCTTCA | 3263 | 66 |

| C3350R | CCTTGAASGACTCHGGRATAC | 3290 | 64 |

| C3490R | CACGGGACAGGTTGATGCC | 3430 | 62 |

| C3630R | GAGMACCTCSACGTTSAGGCACA | 3335 | 70 |

| C3500R | TCGTCDCGBGACAGGTTGATG | 3433 | 66 |

| C2700F | CGWATGAACATYGGBCAGGT | 2714 | 60 |

| C3130R | TCCATYTCRCCRAARCGCTG | 3140 | 62 |

The position of a primer is relative to that of the Corynebacterium diphtheriae rpoB gene sequence (GenBank accession no. AY492230).

Tm, melting temperature.

Bacterial DNA was extracted from a heavy suspension of strains by using the QIAamp blood kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the recommendations of the manufacturer. All PCR mixtures contained 2.5 × 10−2 U of Taq polymerase per μl; 1× Taq buffer; 1.8 mM MgCl2 (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Cergy Pontoise, France); dATP, dCTP, dTTP, and dGTP (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Hilden, Germany) at concentrations of 200 μM each; and each primer (Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium) at a concentration of 0.2 μM. The PCR mixtures were subjected to 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, primer annealing for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 2 min. Every amplification program began with a denaturation step of 95°C for 2 min and ended with a final elongation step of 72°C for 10 min. Determination of the complete sequences of the rpoB sequence ends was achieved by use of the sequences of both the 3′ and the 5′ ends of the gene and amplification by PCR with the Universal GenomeWalker kit (Clontech Laboratories, Palo Alto, Calif.). Briefly, genomic DNA was digested with EcoRV, DraI, PvuII, StuI, and ScaI. The DNA fragments were then ligated with a GenomeWalker adaptor, which had one blunt end and one end with a 5′ overhang. The ligation mixture with the adaptor and the genomic DNA fragments were used as templates for the PCR. This PCR was performed by use of an adaptor primer supplied by the manufacturer and specific primers to walk through the DNA sequence downstream. For the amplification, 1.5 U of Elongase (Boehringer Mannheim) was used with 10 pmol of each primer, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 20 mM, 10 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1.6 mM MgCl2, and 5 μl of template with a final volume of 50 μl. Amplicons were purified for sequencing by use of a QIAquick spin PCR purification kit (Qiagen) by the protocol of the supplier. Sequencing reactions were carried out with the reagents of the ABI Prism 3100 DNA sequencer (dRhod.Terminator RR Mix; Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems) by the standard automated sequencer protocol.

Determination of discriminative partial sequences in 16S rRNA and rpoB genes.

In order to search for parts of sequences with high degrees of variability bordered by conserved regions, we used SVARAP software (Sequence Variability Analysis Program [http://ifr48.free.fr/recherche/jeu_cadre/jeu_rickettsie.html]) (9). After this analysis was done, the most polymorphic areas in rpoB were identified, and primers designed to be specific for the border conserved region were used for PCR amplification of this region. The PCR conditions that incorporated this consensus primer pair (C2700F-C3130R; Table 2) were the same as those described above. These primers were then used for amplification and sequencing of the hypervariable region for all the strains studied in this work.

rpoB sequence analysis.

The nucleotide sequences of the rpoB gene fragments obtained were processed into sequence data with Sequence Analysis Software (Applied Biosystems), and partial sequences were combined into a single consensus sequence with Sequence Assembler Software (Applied Biosystems). All GenBank accession numbers are listed in Table 1. Multiple-sequence alignments and percent similarities of the rpoB and 16S rRNA genes between the different species were obtained with the CLUSTAL W program (18) on the EMBL-EBI web server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/). Phylogenetic trees were obtained from DNA sequences by three different methods: the neighbor-joining, maximum-parsimony, and maximum-likelihood methods (4). Bootstrap replicates were performed in order to estimate the reliabilities of the nodes of the phylogenetic trees obtained. Bootstrap values were obtained from 1,000 trees generated randomly with the SEQBOOT program in the PHYLIP software package.

RESULTS

rpoB sequences of Corynebacterium species.

Almost complete rpoB gene sequences were determined for all strains. The rpoB sequence was more polymorphic than the 16S rDNA sequence. This higher degree of polymorphism was particularly evident for species not well differentiated by 16S rDNA sequence analysis (Table 3), as among the 11 pairs of species with 16S rRNA gene similarities ranging from 98.5 to 99.7%, the similarities of the rpoB gene ranged from 84.9 to 96.6%. The means for the similarities between the 16S rRNA gene and rpoB gene sequences among these 11 pairs were statistically significant. This higher degree of polymorphism was also significant when it was calculated on the basis of range site variability (RSV) (Fig. 1). RSVs of ≥10 were observed in the rpoB gene for 44 of 67 windows of 50 nucleotides (WOFN) and in the 16S rRNA gene for 5 of 27 WOFN (P < 0.001 by the chi-square test). Likewise, RSVs of ≥20 were observed in the rpoB gene for 13 of 67 WOFN and in the 16S rRNA gene for 0 of 27 WOFN (P = 0.008 by Fisher's exact test). The similarity between the two C. afermentans subspecies was 98.2% and, thus, was 1.6% above the highest level of similarity between two species.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of similarities of 16S rRNA and rpoB gene sequences between the two subspecies of C. afermentans and among the 11 pairs of closely related species, with statistical comparison of mean similarities

| Species or subspecies compared | % Similarity

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rDNA |

ropB gene

|

||

| Complete sequenceb | Partial sequencec | ||

| Closely related speciesa | |||

| C. diphtheriae-C. ulcerans | 98.5 | 86 | 87.9 |

| C. diphtheriae-C. pseudotuberculosis | 98.5 | 84.9 | 87.9 |

| C. ulcerans-C. pseudotuberculosis | 99.7 | 93.6 | 93 |

| C. pseudodiphtheriticum-C. propinquum | 99.3 | 89.7 | 93.9 |

| C. aurimucosum-C. singulare | 99 | 94.2 | 93.9 |

| C. aurimucosum-C. minutissimum | 98.7 | 94.6 | 93.9 |

| C. singulare-C. minutissimum | 98.9 | 93.8 | 95.5 |

| C. xerosis-C. freneyi | 98.7 | 96.6 | 95.9 |

| C. macginleyi-C. accolens | 98.7 | 93.3 | 91.7 |

| C. sundsvallens-C. thomssenii | 98.9 | 90.4 | 91 |

| C. mucifaciens-C. afermentans | 98.5 | 94 | 92.4 |

| Mean | 98.85 | 91.91 | 92.45 |

| C. afermentans subsp. afermentans- C. afermentans subsp. lipophilum | 99.8 | 98.2 | 96.6 |

Determined on the basis of ≥98.5% similarity of the 16S rRNA gene sequence.

P = 0.03 compared to the results for 16S rDNA (Student's t test).

P = 0.01 compared to the results for 16S rDNA (Student's t test).

Phylogenetic analysis.

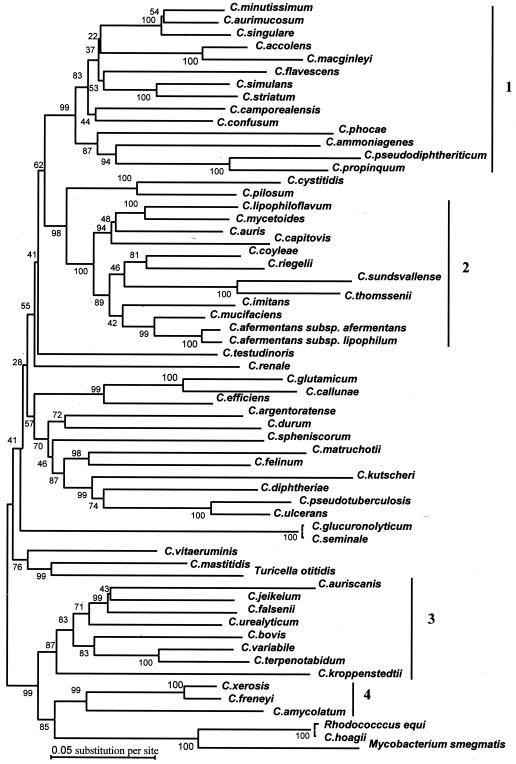

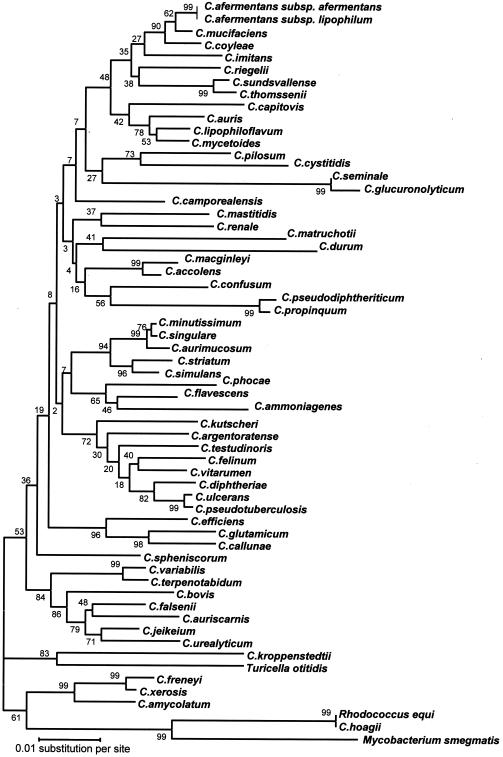

On the basis of rpoB gene sequence analysis, phylogenetic analysis by the neighbor-joining, maximum-parsimony, and maximum-likelihood methods provided similar and reliable organizations for the four clusters supported by high bootstrap values (Fig. 2). On the contrary, only cluster 4 was evidenced when 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis was used (Fig. 3). The bootstrap values at the nodes were in all cases higher than those observed by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Values ≥95% were observed for 14 of 55 nodes for the 16S rRNA gene, whereas values ≥95% were observed for 24 of 55 nodes for the rpoB gene (P = 0.004 by the chi-square test). For some species, such as Corynebacterium testudinoris, Corynebacterium renale, Corynebacterium seminale, and Corynebacterium glucuronolyticum, the phylogenetic position was more difficult to assess. The position of T. otitidis in a genus separate from Corynebacterium is also questionable. Study of the rpoB gene confirms that the genus Rhodococcus is different from Corynebacterium and that Corynebacterium hoagii is not another species but is R. equi and that C. seminale and C. glucuronolyticum are the same species (http://www.bacterio.cict.fr/c/corynebacterium.html).

FIG. 2.

Dendrogram representing the phylogenetic relationships of Corynebacterium species obtained by the neighbor-joining method. The tree was derived from the alignments of rpoB gene sequences. The support of each branch, as determined from 1,000 bootstrap samples, is indicated by the value at each node (in percent).

FIG. 3.

Dendrogram representing the phylogenetic relationships of Corynebacterium species obtained by the neighbor-joining method. The tree was derived from alignment of 16S rRNA gene sequences. The support of each branch, as determined from 1,000 bootstrap samples, is indicated by the value at each node (in percent).

Strain identification.

Four highly variable zones were determined by the use of SVARAP software (Fig. 1). These zones were between positions 1 and 450, 800 and 1100, 1400 and 1750, and 2750 and 3200. Attempts to design universal primers that amplify hypervariable areas were unsuccessful for the first three regions. We designed a consensus primer pair (C2700F-C3130R) that allowed the successful amplification of the region in all Corynebacterium species, R. equi, and T. otitidis between positions 2750 and 3200. The amplified fragment was from 434 to 452 bp, depending on the species. Interestingly, this region was the most variable one (Fig. 1). The similarities observed in the partial rpoB sequence were also significantly less than those observed in the 16S rRNA gene and ranged from 87.9 to 95.9% (Table 3). The similarity between the two C. afermentans subspecies was 96.6% and was thus 0.7% greater than the highest degree of similarity between two species.

DISCUSSION

The description of new bacterial species at present is based on the results of DNA-DNA hybridization and the description of phenotypic characteristics, so-called polyphasic classification data (7, 19). However, DNA-DNA hybridization is difficult to perform, expensive, technically complex, and labor-intensive. The scarcity of reproducible and distinguishable characters frequently limits phenotypic characterization and, thus, phenotype-based identification in routine clinical microbiology laboratories. The development of gene amplification and sequencing, especially that of 16S rRNA gene sequences, has simplified the taxonomy and identification of bacteria, particularly those lacking distinguishable phenotypic characteristics. However, the 16S rDNA sequences of Corynebacterium spp. are not variable enough to ensure confident results from phylogenetic studies based on high bootstrap values (Fig. 3) or to allow determination of a short sequence for accurate identification (Fig. 1). Our data, based on the rpoB sequences of these bacteria, confirm that this gene is significantly more polymorphic than the 16S rRNA gene, and we propose that it be used to replace or complement the 16S rRNA gene for phylogenetic studies of Corynebacterium. Deeply branching nodes were supported by high bootstrap values and allowed the identification of four clusters (Fig. 2). Even among species not resolved into clusters, some groups of bacteria were confidently identified, such as groups containing Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, Corynebacterium ulcerans, and Corynebacterium kutscheri.

The high similarity values for the 16S rRNA gene sequences observed among closely related Corynebacterium spp. indicate that the complete sequence should be determined for accurate sequence-based identification (Table 3). By using SVARAP software, we have designed universal primers for rpoB that allow amplification and sequencing of a 434- to 452-bp fragment polymorphic enough to ensure accurate identification of all Corynebacterium spp. The highest degree of similarity of this partial sequence between two species was 95.9%, whereas it was 99.7% for the complete 16S rRNA gene (Table 3), a sequence nearly four times longer. Moreover, the partial sequences of the rpoB genes of two subspecies of C. afermentans had a similarity of 96.6%, which was thus 0.7% above the limit of similarity between two different species. This difference was only 0.1% for the complete 16S rRNA gene sequence, rendering it impossible to distinguish a subspecies from a closely related species only on the basis of this sequence. This difference was even higher (1.6%) when the complete rpoB sequence was considered. From these data, the cutoff for the definition of species and subspecies in the genus Corynebacterium based on the complete rpoB sequence can be made on the basis of similarities of <96.6 and >98%, respectively. These cutoffs are in the same range as those observed for the genera Bartonella, Afipia, and Bosea (12, 9). However, the similarities of a large collection of different strains within particular species would have to be determined for validation of these cutoffs.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to E. Falsen for providing some of the Corynebacterium strains as a gift.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collins, M. D., R. A. Burton, and D. Jones. 1998. Corynebacterium amycolatum sp. nov., a new mycolic acid-less Corynebacterium species from human skin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 49:349-352. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins, M. D., E. Falsen, E. Akervall, B. Sjödén, and N. Alvarez. 1998. Characterization of a novel non-mycolic acid containing Corynebacterium: description of Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 48:1449-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drancourt, M., and D. Raoult. 2002. rpoB gene sequence-based identification of Staphylococcus species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1333-1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felsenstein, J. 1989. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2). Cladistics 5:164-166. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Funke, G., and K. A. Bernard. 1999. Coryneform gram-positive rods, p. 319-345. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington D.C.

- 6.Funke, G., A. von Graevenitz, J. E. Clarridge III, and K. A. Bernard. 1997. Clinical microbiology of coryneform bacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 10:125-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimont, P. A. D. 1988. Use of DNA reassociation in bacterial classification. Can. J. Microbiol. 34:541-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janda, W. M. 1998. Corynebacterium species and the coryneform bacteria, part I: new and emerging species in the genus Corynebacterium. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 20:41-52. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khamis, A., P. Colson, D. Raoult, and B. La Scola. 2003. Usefulness of rpoB gene sequencing for identification of Afipia and Bosea species, including a strategy for the choice of discriminative partial sequences. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:6740-6749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim, B. J., S. H. Lee, M. A. Lyu, S. J. Kim, G. H. Bai, G. T. Chae, E. C. Kim, C. Y. Cha, and Y. H. Kook. 1999. Identification of mycobacterial species by comparative sequence analysis of the RNA polymerase gene (rpoB). J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1714-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko, K. S., H. K. Lee, M. Y. Park, K. H. Lee, Y. J. Yun, S. Y. Woo, H. Miyamoto, and Y. H. Kook. 2002. Application of RNA polymerase beta-subunit gene (rpoB) sequences for the molecular differentiation of Legionella species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2653-2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Scola, B., Z. Zeaiter, A. Khamis, and D. Raoult. 2003. Gene sequence based criteria for species definition in bacteriology: the Bartonella paradigm. Trends Microbiol. 11:318-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mollet, C., M. Drancourt, and D. Raoult. 1997. rpoB sequence analysis as a novel basis for bacterial identification. Mol. Microbiol. 26:1005-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pascual, C., P. A. Lawson, J. A. E. Farrow, M. N. Gimenez, and M. D. Collins. 1995. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Corynebacterium based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:724-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Renesto, P., J. Gouvernet, M. Drancourt, V. Roux, and D. Raoult. 2001. Use of rpoB gene analysis for detection and identification of Bartonella species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:430-437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruimy, R., P. Riegel, P. Boiron, H. Montiel, and R. Christen. 1995. Phylogeny of the genus Corynebacterium deduced from analyses of small-subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:740-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siebert, P. D., A. Chenchik, D. E. Kellogg, K. A. Lukyanov, and S. A. Lukyanov. 1995. An improved PCR method for walking in uncloned genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:1087-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wayne, L. G., D. J. Brenner, R. R. Colwell, P. A. D. Grimont, O. Kandler, M. L. Krichevsky, L. H. Moore, W. E. C. Moore, R. G. E. Murray, E. Stackebrandt, M. P. Starr, and H. G. Trüper. 1987. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Reconciliation of Approaches to Bacterial Systematics. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 37:463-464. [Google Scholar]