Abstract

Phage typing and DNA macrorestriction fragment analysis by pulsed-field electrophoresis (PFGE) were used for the epidemiological subtyping of a collection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O157:H7 strains isolated in Spain between 1980 and 1999. Phage typing distinguished a total of 18 phage types among 171 strains isolated from different sources (67 humans, 82 bovines, 12 ovines, and 10 beef products). However, five phage types, phage type 2 (PT2; 42 strains), PT8 (33 strains), PT14 (14 strains), PT21/28 (11 strains), and PT54 (16 strains), accounted for 68% of the study isolates. PT2 and PT8 were the most frequently found among strains from both humans (51%) and bovines (46%). Interestingly, we detected a significant association between PT2 and PT14 and the presence of acute pathologies. A group of 108 of the 171 strains were analyzed by PFGE, and 53 distinct XbaI macrorestriction patterns were identified, with 38 strains exhibiting unique PFGE patterns. In contrast, phage typing identified 15 different phage types. A total of 66 phage type-PFGE subtype combinations were identified among the 108 strains. PFGE subtyping differentiated between unrelated strains that exhibited the same phage type. The most common phage type-PFGE pattern combinations were PT2-PFGE type 1 (1 human and 11 bovine strains), PT8-PFGE type 8 (2 human, 6 bovine, and 1 beef product strains), PT2-PFGE subtype 4A (1 human, 3 bovine, and 1 beef product strains). Nine (29%) of 31 human strains showed phage type-PFGE pattern combinations that were detected among the bovine strains included in this study, and 26 (38%) of 68 bovine strains produced phage type-PFGE pattern combinations observed among human strains included in this study, confirming that cattle are a major reservoir of strains pathogenic for humans. PT2 and PT8 strains formed two groups which differed from each other in their motilities, stx genotypes, PFGE patterns, and the severity of the illnesses that they caused.

Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), also called verotoxin-producing E. coli, is the most important recently emerged group of food-borne pathogens (11, 39, 48, 53). STEC is a major cause of gastroenteritis that may be complicated by hemorrhagic colitis (HC) or hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), which is the main cause of acute renal failure in children (8, 60, 65). Since its identification as a pathogen in 1982, STEC O157:H7 has been the cause of a series of outbreaks in Europe, Japan, and North America (39, 62, 67). Domestic ruminants, especially cattle, sheep, and goats, have been implicated as the principal reservoir (13, 16, 17, 18). Transmission occurs through the consumption of undercooked meat, unpasteurized dairy products, and vegetables or water contaminated by the feces of carriers, because STEC strains are found as part of the normal intestinal flora of the animals. Person-to-person transmission has also been documented (39, 53). Most outbreaks and sporadic cases of HC and HUS have been attributed to strains of enterohemorrhagic serotype O157:H7 (8, 41, 60). Unlike other E. coli strains, STEC O157:H7 does not ferment sorbitol and is β-d-glucuronidase negative. These differences make it easy to identify O157:H7 strains in clinical samples and food products (14, 21, 40).

STEC elaborates two potent phage-encoded cytotoxins called Shiga toxins (Stx1 and Stx2) or Verotoxins (VT1 and VT2) (39, 53). In addition to toxin production, another virulence-associated factor expressed by STEC is a protein called intimin, which is encoded by the eae gene and which is responsible for the intimate attachment of STEC to intestinal epithelial cells, causes attaching-and-effacing lesions in the intestinal mucosa (1, 37). A factor that may also affect the virulence of STEC is the enterohemolysin (Ehly), also called enterohemorrhagic E. coli hemolysin (EHEC hlyA), which is encoded by the ehxA gene (9, 59).

Epidemiological investigations of outbreaks caused by STEC O157:H7 have been greatly assisted by laboratory procedures for the subtyping of isolates. During the last decade, numerous subtyping methodologies have been developed, but phage typing and macrorestriction fragment analysis of DNA by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) have become the most commonly used (2, 3, 5, 6, 28, 29, 36, 56, 64).

STEC O157:H7 has been isolated in Spain since 1980 (12), but little is known about the dominant types in humans and animals or their genetic relatedness. The aim of this study was to subtype by phage typing and PFGE fingerprinting methods a large collection of STEC O157:H7 strains isolated from different sources in Spain over a period of almost 20 years in order to determine the genetic relationships among strains of different human and animal origins. In addition, the aim was to study the association of phage types with the severity of illness in human patients. This is the first study in Spain of a large collection of STEC O157:H7 isolates by the use of PFGE and phage typing as epidemiological tools.

(The data from this study were partly presented previously as a poster communication [A. Mora, M. Blanco, J. E. Blanco, G. Dahbi, M. P. Alonso, A. Stirrat, F. Thomson-Carter, M. A. Usera, R. Bartolomé, G. Prats, and J. Blanco, 5th Int. Symp. Shiga Toxin (Verocytotoxin)-Producing E. coli Infect., abstr. P195, p. 177, 2003].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Origins and isolation of STEC O157:H7 strains.

A collection of 171 STEC O157 strains that originated from different geographic regions of Spain (Castilla, Cataluña, Extremadura, Galicia, Madrid, Navarra, Valencia, Islas Baleares, and Canarias) were isolated from various sources (humans, bovines, ovines, and beef products) over a period of almost 20 years (1980 to 1999). They comprised (i) 41 isolates (31 isolates from cattle and 10 isolates from human) epidemiologically related in different groups and (ii) 130 isolates not known to be epidemiologically related (57 isolates from humans, 51 isolates from cattle, 12 isolates from ovines, and 10 isolates from raw beef products). The majority of strains included in the present study were obtained from previously published studies (12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 48, 55, 57), and the procedures for their isolation are described in detail in the reports of those studies.

Biotyping, serotyping, and phage typing.

All STEC O157:H7 strains were identified biochemically with the API 20E system (bioMerieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France). Fermentation of sorbitol and β-d-glucuronidase activity were investigated on sorbitol MacConkey agar and Chromocult Coliform agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), respectively, after 24 h of incubation.

O- and H-antigen determinations were carried out by the method described by Guinée et al. (31) by using all available type O (O1 to O181) and type H (H1 to H56) antisera in the Laboratorio de Referencia de E. coli, Lugo, Spain. All antisera were obtained and absorbed with the corresponding cross-reacting antigens to remove the nonspecific agglutinins. The O antisera were produced in the Laboratorio de Referencia de E. coli (http://www.lugo.usc.es/ecoli), and the H antisera were obtained from the Statens Serum Institut (Copenhagen, Denmark).

Phage typing was performed by the method of Khakria et al. (42) in the Centro Nacional de Microbiología (Madrid, Spain) with the phages provided by The National Laboratory for Enteric Pathogens, Laboratory for Disease Control, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The 16 different phages used were capable of identifying 88 phage types.

Production and detection of Shiga toxins (Verotoxins) in Vero and HeLa cells.

For the production of Shiga toxins, one loopful of each strain was inoculated into a 50-ml Erlenmeyer flask containing 5 ml of tryptone soy broth (pH 7.5) with mitomycin C, incubated for 20 h at 37°C (shaken at 200 rpm), and then centrifuged (6,000 × g) for 30 min at 4°C. The Vero and HeLa cell culture assays were performed with nearly confluent cell monolayers grown in plates with 24 wells. At the time of assay, the growth medium (RPMI with polymyxin B sulfate) was changed (0.5 ml per well) and 75 μl of undiluted culture supernatant was added. The cells were incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and the morphological changes observed in the cells after 24 and 48 h of incubation were detected with an inverted phase-contrast microscope (16).

PCR of stx1, stx2, ehxA, eae, O157 rfbE, and fliCh7 genes.

All strains were tested as described elsewhere (17) with primers specific for the genes encoding the Stx1 and Stx2 toxins (the stx1 and stx2 genes, respectively) (17), EHEC hemolysin (the ehxA gene) (59), the intimin (eae gene and the eae-γ1 variant gene) (17), the O157 antigen (O157 rfbE gene) (25), and the H7 antigen (fliCh7 gene) (27) (Table 1). The primers used to amplify the stx1 and stx2 genes were capable of detecting Stx1 and Stx2 and the variants Stx1c, Stx2c, Stx2d, and Stx2e.

TABLE 1.

Primer sequences and lengths of PCR amplification products

| Gene | Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′-3′) | Fragment size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| stx1 | VT1-A | CGCTGAATGTCATTCGCTCTGC | 302 | Blanco et al. (17) |

| VT1-B | CGTGGTATAGCTACTGTCACC | |||

| stx2 | VT2-A | CTTCGGTATCCTATTCCCGG | 516 | Blanco et al. (17) |

| VT2-B | CTGCTGTGACAGTGACAAAACGC | |||

| ehxA | HlyA1 | GGTGCAGCAGAAAAAGTTGTAG | 1,551 | Schmidt et al. (59) |

| HlyA4 | TCTCGCCTGATAGTGTTTGGTA | |||

| eae | EAE-1 | GAGAATGAAATAGAAGTCGT | 775 | Blanco et al. (17) |

| EAE-2 | GCGGTATCTTTCGCGTAATCGCC | |||

| eae-γ1 | EAE-F | ATTACTGAGATTAAGGCTGAT | 739 | Blanco et al. (17) |

| EAE-C1 | CTCCAGAACGCTGCTCACT | |||

| O157 rfbE | O157-AF | AAGATTGCGCTGAAGCCTTTG | 497 | Desmarchelier et al. (25) |

| O157-AR | CATTGGCATCGTGTGGACAG | |||

| fliCh7 | H7-F | GCGCTGTCGAGTTCTATCGAGC | 625 | Gannon et al. (27) |

| H7-R | CAACGGTGACTTTATCGCCATTCC |

PFGE.

PFGE was performed in a CHEF MAPPER system (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom) by the method of Krause et al. (43). Cleavage of the agarose-embedded DNA was achieved with XbaI (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom), according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Run times and pulse times were 15 to 50 s for 22 h with linear ramping. PFGE was used to establish clonal relatedness and diversity among a representative group of 108 of those 171 strains. The PFGE patterns (pulsotypes and subtypes) were interpreted by the method described by Tenover et al. (63). Strains with no fragment differences were considered indistinguishable (i.e., they had the same pulsotype, named pulsotypes 1, 2, 3, etc.). To name the different pulsotypes, a single-fragment difference was defined as significant, and the subtypes were coded as A, B, C, and D.

RESULTS

Phenotypic properties and phage types.

None of the 171 STEC O157:H7 strains evaluated in this study fermented sorbitol after overnight incubation, and all strains were β-d-glucuronidase negative.

The 171 strains were grouped into 18 phage types (Table 2). However, five phage types, phage type 2 (PT2; 42 strains), PT8 (33 strains), PT14 (14 strains), PT21/28 (11 strains), and PT54 (16 strains), accounted for 68% of the study group of strains. PT2 and PT8 were the most frequently found among both human (51%) and bovine (46%) strains, whereas PT54 (42%) was the most prevalent among ovine strains, and PT21/28 (30%) was the most prevalent among beef product strains. Twenty-four strains reacted with the typing phages but did not conform to any recognized phage type and are referred to as reacts but does not conform (RDNC).

TABLE 2.

Phage types of STEC O157:H7 strains isolated of different origins

| Phage type | No. of isolates of the following origin:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 171) | Human (n = 67) | Bovine (n = 82) | Beef (n = 10) | Ovine (n = 12) | |

| PT2 | 42 | 19 | 21 | 2 | 0 |

| PT4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| PT8 | 33 | 15 | 17 | 1 | 0 |

| PT14 | 14 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| PT21/28 | 11 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 0 |

| PT23 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| PT26 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| PT27 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| PT31 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT32 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| PT34 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| PT39 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| PT45 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| PT50 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PT51 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| PT54 | 16 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 5 |

| PT63 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| PT87 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RDNC | 24 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 2 |

One hundred forty-seven (86%) of 171 STEC O157:H7 strains expressed the H7 antigen and 24 (14%) were nonmotile (NM). The majority of NM strains belonged to PT8 (15 strains), followed by PT14 (4 strains), PT2 (2 strains), PT54 (2 strains), and RDNC (1 strain).

All 171 STEC O157:H7 strains were cytotoxic to Vero and HeLa cells.

Genes stx1, stx2, ehxA, eae, O157 rfbE, and fliCh7.

PCR demonstrated that the majority of strains with the same phage type showed the same stx1 and stx2 gene patterns. Thus, 41 of 42 PT2 strains were stx2, 28 of 33 PT8 strains were stx1 stx2, all 11 PT21/28 strains were stx1 stx2, and all 6 PT34 strains and all 16 PT54 strains were stx2. Also, four of five PT39 strains were stx1 stx2 (Table 3). Globally, 3 (2%) strains carried stx1 genes, 104 (61%) strains possessed stx2 genes, and 64 (37%) possessed both the stx1 and the stx2 genes. All 171 STEC O157:H7 strains possessed the eae-γ1, ehxA, O157 rfbE, and fliCh7 genes.

TABLE 3.

Phage types and Shiga toxin genes of STEC O157:H7

| Phage type | No. of isolates

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 171) | stx1 (n = 3) | stx2 (n = 104) | stx1stx2 (n = 64) | |

| PT2 | 42 | 0 | 41 | 1 |

| PT4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| PT8 | 33 | 1 | 4 | 28 |

| PT14 | 14 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| PT21/28 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| PT23 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| PT26 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| PT27 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| PT31 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| PT32 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| PT34 | 6 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| PT39 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| PT45 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| PT50 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| PT51 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| PT54 | 16 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| PT63 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| PT87 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| RDNC | 24 | 1 | 19 | 4 |

Association of disease with phage types and presence of asymptomatic carriers.

When we studied the relationship between phage types and the clinical symptoms of the patients, we observed that PT2 (86%) and PT14 (100%) strains were associated with acute pathologies (HC, HUS, and/or acute renal failure) at a higher percentage than PT8 strains (38%) (Table 4). All O157:H7 PT2 strains isolated from patients were stx2 positive; and among the PT14 strains, three strains were stx1 stx2 (including a strain from a patient and an asymptomatic carrier who was a relative of the patient) and four strains carried stx2.

TABLE 4.

Phage types of human STEC O157:H7 strains and clinical symptoms

| Phage type | No. of strains causing the following clinical symptomsa:

|

No. of strains causing HC, HUS, and/or ARF/total no. of strains (%)b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | AP/VO | D | HC | HUS | ARF | AC | ? | ||

| PT2 | 19 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 12/14 (86) |

| PT4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| PT8 | 15 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5/13 (38) |

| PT14 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4/4 (100) |

| PT21/28 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| PT26 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| PT31 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| PT34 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| PT39 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/3 (33) |

| PT50 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| PT54 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/3 (67) |

| PT63 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| PT87 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| RDNC | 11 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7/10 (70) |

AP/VO, abdominal pain and/or vomiting; D, nonbloody diarrhea; ARF, acute renal failure; AC, asymptomatic carrier; ?, clinical history of the patient not available.

All patient strains not including those isolated from patients whose clinical history was not available.

The presence of asymptomatic carriers among the relatives of patients was analyzed when it was possible, and we detected them in five cases (Table 5). As expected, strains isolated from a patient and an asymptomatic carrier related to the patient showed the same phage type (PT2, two cases in 1997 and one case in 1998; PT8, one case in 1999; PT14, one case in 1995).

TABLE 5.

Phage type-PFGE pattern combinations corresponding to human cases associated with asymptomatic carriers

| Case no.a | Strain code | City-yr | Phage type | stx type | PFGE type and subtype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C11-AC | O157-249 | Lugo-1997 | PT2 | stx2 | 2A |

| C11-P | O157-238 | PT2 | stx2 | 1 | |

| C6-AC | O157-186 | Lugo-1997 | PT2 | stx2 | 2A |

| C6P | O157-167 | PT2 | stx2 | 5 | |

| C15-AC | O157-436 | Lugo-1998 | PT2 | stx2 | 11 |

| C15-P | O157-407 | PT2 | stx2 | 11 | |

| C18-AC | O157-508 | Lugo-1999 | PT8 | stx1stx2 | Not realized |

| C18 | O157-487 | PT8 | stx1stx2 | Not realized | |

| C1-AC | O157-66 | Lugo-1995 | PT14 | stx1stx2 | DNA degraded |

| C1-P | O157-59 | PT14 | stx1stx2 | 17 |

AC, asymptomatic carrier (relative of positive patient living in the same house); P, patient.

Analysis of PFGE patterns.

Amongthe 171 STEC O157:H7 strains characterized by phage typing and PCR, a representative group of 108 of those 171 strains were subjected to fingerprinting by PFGE with the XbaI restriction enzyme to digest the genomic DNA. A total of 53 macrorestriction patterns were detected among the 108 strains (35 types with a total of 53 subtypes). However, 53% of the strains produced 1 of these 11 types (PFGE types 1, 2A, 4A, 5, 8, 14A, 14B, 17, 18, 19A, and 23A) and 39% of the strains belonged to only 6 types (PFGE types 1, 4A, 8, 18, 19A, and 23A) (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Phage type-PFGE subtype combinations among STEC O157:H7

| PFGE type and subtype | No. of strains (no. of strains and origin) | Phage type (no. of strains) | Year (no. of strains and origin) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 (1H, 11B) | PT2 (12) | 1997 (1H) |

| 1998 (7B) | |||

| 1999 (4B) | |||

| 2A | 3 (2H, 1B) | PT2 (3) | 1995 (1B) |

| 1997 (2H) | |||

| 2B | 1 (1H) | PT2 (1) | 1996 (1H) |

| 2C | 1 (1B) | PT54 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| 3 (1-2A) | 1 (1B) | PT2 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| 4A | 5 (1H, 3B, 1M) | PT2 (5) | 1996 (1H) |

| 1997 (1M) | |||

| 1998 (3B) | |||

| 4B | 1 (1H) | PT2 (1) | 1998 (1H) |

| 4C | 1 (1M) | PT4 (1) | 1999 (1M) |

| 4D | 1 (1B) | PT54 (1) | 1999 (1B) |

| 5 | 3 (3H) | PT2 (3) | 1991 (1H) |

| 1997 (2H) | |||

| 6 | 1 (M) | PT2 (1) | 1995 (1M) |

| 7 | 1 (B) | PT2 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| 8 | 10 (3H, 6B, 1M) | PT2 (1) | 1997 (1H) |

| PT8 (9) | 1997 (1H) | ||

| 1998 (1H, 1M) | |||

| 1999 (6B) | |||

| 9 | 1 (1B) | PT2 (1) | 1994 (1B) |

| 10 | 2 (1H, 1B) | PT2 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| PT54 (1) | 1998 (1H) | ||

| 11 | 2 (2H) | PT2 (2) | 1998 (2H) |

| 12 | 1 (1H) | PT2 (1) | 1991 (1H) |

| 13 | 1 (1B) | PT2 (1) | 1995 (1B) |

| 14A | 3 (1H, 2B) | PT8 (3) | 1995 (1H, 2B) |

| 14B | 3 (3B) | PT8 (2) | 1998 (2B) |

| PT54 (1) | 1998 (1B) | ||

| 15 | 2 (H) | PT8 (2) | 1996 (2H) |

| 16A | 2 (1H, 1B) | PT14 (1) | 1991 (1B) |

| PT39 (1) | 1996 (1H) | ||

| 16B | 2 (2B) | PT8 (1) | 1995 (1B) |

| PT14 (1) | 1988 (1B) | ||

| 17 | 3 (2H, 1B) | PT8 (2) | 1997 (1H) |

| 1998 (1B) | |||

| PT14 (1) | 1995 (1H) | ||

| 18 | 4 (1H, 3B) | PT8 (1) | 1998 (1H) |

| PT14 (2) | 1999 (2B) | ||

| PT32 (1) | 1999 (1B) | ||

| 19A | 6 (1H, 3B, 2O) | PT14 (2) | 1997 (2O) |

| PT54 (1) | 1999 (1B) | ||

| RDNC (3) | 1997 (1H) | ||

| 1999 (2B) | |||

| 19B | 1 (1B) | PT23 (1) | 1999 (1B) |

| 19C | 1 (1B) | RDNC (1) | 1999 (1B) |

| 19D | 1 (1B) | RDNC (1) | 1999 (1B) |

| 20 | 1 (1B) | PT8(1) | 1999 (1B) |

| 21 | 2 (2H) | PT14 (2) | 1993 (1H) |

| 1998 (1H) | |||

| 22 | 1 (1H) | PT14 (1) | 1986 (1H) |

| 23A | 5 (5B) | PT21/28 (3) | 1998 (3B) |

| PT26 (1) | 1998 (1B) | ||

| PT45 (1) | 1998 (1B) | ||

| 23B | 1 (1B) | PT21/28 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| 23AB | 1 (1B) | PT21/28 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| 23C | 1 (1B) | PT21/28 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| 24 | 1 (1H) | PT21/28 (1) | 1989 (1H) |

| 25 | 2 (2B) | PT23 (2) | 1998 (2B) |

| 26A | 2 (2B) | PT34 (2) | 1998 (2B) |

| 26B | 1 (1B) | PT27 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| 26C | 1 (1B) | PT34 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| 27 | 1 (1M) | PT21/28 (1) | 1995 (1M) |

| 28 | 1 (1M) | PT32 (1) | 1995 (1M) |

| 29 | 1 (1H) | PT34 (1) | 1992 (1H) |

| 30A | 1 (1B) | PT45 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| 30B | 2 (2B) | RDNC (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| PT51 (1) | 1998 (1B) | ||

| 31A | 1 (1H) | PT54 (1) | 1998 (1H) |

| 31B | 1 (1O) | PT54 (1) | 1997 (1O) |

| 32 | 1 (1B) | PT54 (1) | 1995 (1B) |

| 33 | 1 (1B) | PT54 (1) | 1998 (1B) |

| 34 | 1 (1B) | RDNC (1) | 1999 (1B) |

| 35A | 1 (1H) | RDNC (1) | 1991 (1H) |

| 35B | 1 (1B) | RDNC (1) | 1980 (1B) |

A total of 108 strains were tested. H, human; B, bovine; M, beef meat; O, ovine.

The most common phage type-PFGE patterns were PT2-PFGE type 1 (1 human and 11 bovine strains), PT8-PFGE type 8 (2 human, 6 bovine, and 1 beef product strains), and PT2-PFGE subtype 4A (1 human, 3 bovine, and 1 beef product strains) (Table 6). Nine (29%) of 31 human strains showed phage type-PFGE pattern combinations detected among bovine strains included in this study, and 26 (38%) of 68 bovine strains produced phage type-PFGE pattern combinations observed among human strains included in this study. The majority of human and bovine strains with the same phage type-PFGE pattern combinations belonged to PT2 and PT8.

It was found that strains with the same phage type showed many different profiles. We also observed the other phenomenon, as strains belonging to different phage types presented the same profile. PT21/28 strains showed the most homogeneous profiles, as six (75%) of the eight strains that belonged to that phage type had the same subtype or a closely related subtype (subtypes 23A, 23B, 23AB, and 23C). Also, phage types PT2 and PT8 presented an important prevalence among certain PFGE types. Only one PT2 strain had a PFGE type common with PT8 strains (type 8) (Table 6).

Forty-one strains were epidemiologically related: 10 human strains (pairs of strains from a patient and from a relative living in the same house who was an asymptomatic carrier) from 5 nonrelated patients living in an area (Lugo) served by the same hospital (Table 5) and 31 cattle strains in seven groups (farms) from the same geographic area (Navarra) and collected during the same period in 1998 from all but one farm (farm 515) (Table 7).

TABLE 7.

Phage type-PFGE pattern combinations in epidemiologically related bovine STEC O157:H7 strainsa

| Farm no./yr | Strain code | Phage type | stx type | PFGE type and subtype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 506-1998 | O157-310 | PT34 | stx2 | 26C |

| O157-330 | PT34 | stx2 | 26A | |

| O157-335 | PT34 | stx2 | 26A | |

| O157-315 | PT21/28 | stx1stx2 | 23AB | |

| 507-1998 | O157-300 | PT23 | stx1stx2 | 25 |

| O157-305 | PT23 | stx1stx2 | 25 | |

| 508-1998 | O157-366 | PT54 | stx2 | 33 |

| 511-1998 | O157-342 | PT2 | stx2 | 1 |

| O157-344 | PT2 | stx2 | 1 | |

| O157-356 | PT2 | stx2 | 3 | |

| O157-351 | PT2 | stx2 | 1 | |

| O157-352 | PT2 | stx2 | 4A | |

| O157-346 | PT2 | stx2 | 1 | |

| O157-354 | PT2 | stx2 | 1 | |

| O157-358 | PT2 | stx2 | 4A | |

| O157-340 | PT2 | stx2 | 1 | |

| O157-348 | PT2 | stx2 | 10 | |

| 512-1998 | O157-360 | RDNC | stx2 | 30B |

| 513-1998 | O157-2801 | PT2 | stx2 | 7 |

| O157-256 | PT21/28 | stx1stx2 | 23A | |

| O157-265 | PT21/28 | stx1stx2 | 23B | |

| O157-274 | PT21/28 | stx1stx2 | 23A | |

| O157-259 | PT21/28 | stx1stx2 | 23C | |

| O157-286 | PT21/28 | stx1stx2 | 23A | |

| O157-271 | PT26 | stx1stx2 | 23A | |

| O157-262 | PT27 | stx2 | 26B | |

| O157-277 | PT45 | stx1stx2 | 30A | |

| O157-289 | PT45 | stx1stx2 | 23A | |

| O157-2681 | PT51 | stx2 | 30B | |

| O157-292 | PT54 | stx2 | 2C | |

| 515-1999 | O157-469 | PT4 | stx2 | 4C |

Farms were visited on only one occasion to collect fecal samples.

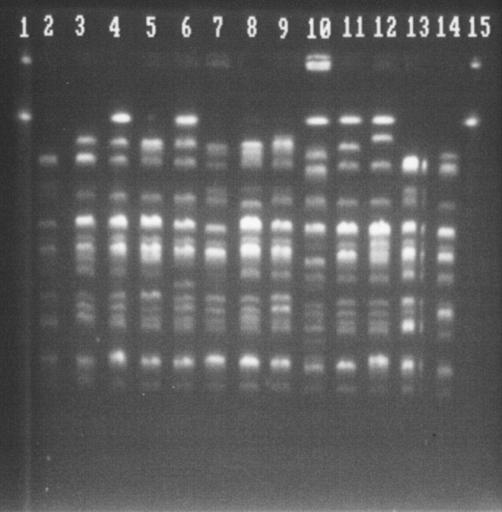

In a comparison of the strains from patients for whom an asymptomatic carrier was detected (Fig. 1; Table 5), each of the strains from two of the pairs of cases (cases C11 and C6) involving patients and their asymptomatic carriers showed different PFGE patterns, even though they showed the same phage type, as expected. Curiously, the strains from both asymptomatic carriers showed the same PFGE subtype, subtype 2A. In case C15 the same PFGE type was detected in both the patient and the asymptomatic carrier, and in case C1, PFGE analysis could be performed with only the strain from the patient, which was PFGE type 17, because the DNA of the strain from the asymptomatic carrier was degraded.

FIG. 1.

PFGE of STEC O157:H7 phage types PT2 (lanes 2 to 12) and PT8 (lanes 13 and 14). Lanes 1 and 15, bacteriophage lambda ladder PFGE marker (Biolabs); lanes 4 (asymptomatic carrier) and 7 (patient) correspond to case 6, PT2-PFGE type 2A and PT2-PFGE type 5, respectively.

In a comparison of the 31 strains from seven farms in Navarra (Table 7), 10 phage types (phage types PT2, PT4, PT21/28, PT23, PT26, PT27, PT34, PT45, PT51, and PT54) and 11 PFGE types with a total of 18 subtypes (subtypes 1, 2C, 3, 4A, 4C, 7, 10, 23A, 23B, 23AB, 23C, 25, 26A, 26B, 26C, 30A, 30B, and 33) were detected among the 31 strains. However, on farm 506 (n = 4) the main phage type-PFGE subtype combination was PT34-PFGE type 26 (3 strains), on farm 511 (n = 10) the main combination detected was PT2-PFGE type 1 (6 strains), and on farm 513 (n = 12) PFGE pattern 23 was detected in a total of 7 strains (PT21/28, 5 strains; PT26, 1 strain; PT45, 1 strain).

DISCUSSION

In Spain, as in many other countries, STEC O157:H7 strains have been isolated from cattle (12, 13, 16, 18), sheep (17, 57), and food (14, 48); and they represent a significant cause of sporadic cases of human infection (15, 55). STEC O157:H7 isolates have caused seven outbreaks in Spain, three of which were associated with PT2 and one of which was associated with PT8 (49, 54); http://www.lugo.usc.es/ecoli/SEROTIPOSOUTBREAKS.htm.

Unlike other E. coli isolates, STEC O157:H7 strains are negative for sorbitol fermentation within 24 h of incubation and do not exhibit β-d-glucuronidase activity. This enables their efficient differential selection from clinical samples and food products on sorbitol-containing MacConkey agar (14, 15, 21, 40). However, phenotypic variants of NM STEC O157:H− that are sorbitol fermentation positive and β-d-glucuronidase positive (mainly strains of PT23 and PT88) have been isolated in Germany, the Czech Republic, and Finland (38, 58); and motile sorbitol fermentation-negative and β-d-glucuronidase-positive atypical STEC O157:H7 strains have been isolated in the United States (32) and Japan (50). In the present study, none of the 171 STEC O157:H7 strains studied fermented sorbitol after 24 h of incubation, and all were β-d-glucuronidase negative.

All 171 STEC O157:H7 strains expressed the O157 antigen and 147 (86%) expressed the H7 antigen in the serotyping studies. A total of 24 (14%) were NM. However, we identified all strains included in the present study as O157:H7 because all 171 STEC strains possessed the O157 rfbE and fliCh7 genes. As in previous studies (10), we have found that the majority of NM strains (15 of 24) belonged to PT8.

Fifteen variants of the eae gene were identified by intimin type-specific PCR assays with oligonucleotide primers complementary to the 3′ ends of the specific intimin genes that encode intimin types α1, α2, β1, β2, γ1, γ2/θ, δ/κ, ɛ, ζ, η, ι, λ, μ, ν, and ξ (18, 68). Like other investigators (10, 11, 52), we detected intimin type γ1 in all STEC O157:H7 eae-positive strains of human and animal origin.

The phage typing procedure represents the only internationally standardized subtyping method with universally accepted interpretive criteria for STEC O157:H7 (3). In recent years, DNA macrorestriction analysis by PFGE has increasingly been used for the molecular subtyping of a wide range of bacterial pathogens, and it is now considered the “gold standard” for the molecular subtyping of many pathogenic organisms (4, 5, 19, 24, 28, 56). For STEC O157:H7, the usefulness of PFGE fingerprinting during outbreak investigations has been demonstrated previously, and in addition, the standardization of PFGE analysis in public health laboratories in the United States has recently been achieved (PulseNet; http://www.cdc.gov/pulsenet/index.htm) (61). As the official Spanish STEC reference center (COLINETWORK-O157 and COLIRED-O157; http://www.lugo.usc.es/ecoli/COLIREDin.html), ourgroup is trying to standardize the PFGE method to create a Spanish national electronic database of PFGE types. This is the first study in Spain of a large collection of STEC O157:H7 strains by the use of PFGE and phage typing as epidemiological tools. The information on the distributions of phage type-PFGE combinations in humans infections, animal reservoirs, and foods in Spain obtained may help to detect reservoirs, trace routes of transmission, and establish the temporal and geographical variations of newly emerging clones or subclones with outstanding virulence, as well as their potential spread in Europe.

At least 88 phage types have been reported for STEC O157:H7 (3), but only 5 of these (phage types PT2, PT8, PT14, PT21/28, and PT54) accounted for 68% of the strains included in this study. PT2 and PT8 were predominant among human and bovine STEC O157:H7 strains in Spain as well as in many other European countries, including Belgium, Finland, Germany, Italy, England, and Scotland (20, 22, 23, 30, 33, 34, 46, 58). PT2 was among the most frequently isolated phage type among STEC O157:H7 strains in 14 different European countries (T. Cheasty, F. Allerberger, L. Beutin, A. Caprioli, A. Heuvelink, H. Karch, S. Lofdahl, D. Pièrard, F. Scheutz, A. Siitonen, and H. Smith, 4th Int. Symp. Workshop Shiga Toxin (Verocytotoxin)-Producing E. coli Infect., abstr. 263, p. 126, 2000). According to their phage types, stx genotypes, and phenotypes, the STEC O157:H7 strains isolated in Spain were very similar to those isolated in other parts of Europe.

In Spain and other countries, the most common phage types among bovine and ovine strains are also common among human strains, supporting the idea that ruminants are a principal reservoir (44). When we grouped the STEC O157 strains by origin (human, bovine, ovine, and beef product sources), some of the phage type-PFGE pattern combinations contained isolates of more than one origin; e.g., 29% of human STEC O157:H7 strains showed phage type-PFGE pattern combinations detected among bovine strains included in this study, and 38% of bovine STEC O157:H7 strains belonged to phage type-PFGE pattern combinations observed among the human strains included in this study, even though none of the samples were known to be epidemiologically related. This finding was also observed by Avery et al. (7), who detected the same PFGE pattern in three cases of human disease and two healthy animals on a farm, although they did not use phage typing as a complementary epidemiological tool in their study. In our study, the majority of human and bovine strains with the same phage type-PFGE pattern combinations belonged to PT2 and PT8. In an interesting study performed by Lahti et al. (44) in Finland, five human infections not associated with each other could be traced to five different dairy farms. The phage types (three cases of infection were caused by PT2 strains) and PFGE patterns of the Finnish human and bovine isolates from the corresponding farms were indistinguishable. In any case, as van Duynhoven et al. pointed out in their study (66)—in which 17 clusters of isolates, including isolates with unknown epidemiological links with at least 95% fragments in common, were detected—we must be aware that except for clusters, PFGE results also identify endemic strains, which are presumed to be clonally related but which have a temporally distant common origin. Like Heuvelink et al. (35), when we examined the strains from seven farms, we also detected the simultaneous presence of more than one strain type among the epidemiologically related cattle strains on three farms (farms 506, 511, and 513) (Table 7), suggesting that there was more than one source of STEC O157 on the farms.Nevertheless, we also detected the predominance of a particular type on the three farms (PT34-stx2-PFGE type 26 on farm 506, PT2 stx2-PFGE type 1 on farm 511, and PT21/28-stx1 stx2-PFGE type 23 on farm 513), suggesting horizontal transmission within the farm.

Spanish PT2 and PT8 strains formed two groups which differed from each other in their motility (H7 expression for PT2 strains versus NM status for PT8 strains), stx genotypes (stx2 for PT2 strains versus stx1 stx2 for PT8 strains), PFGE patterns (mainly PFGE types 1 and 4A for PT2 strains versus mainly PFGE types 8 and 14 for PT8 strains), and the severity of the illness that they caused (only PT2 strains were associated with acute pathologies). Beutin et al. (10) found similar results in Germany. Both STEC O157:H7 PT2 strains and STEC O157:H7 PT8 strains accounted for 102 (61%) of 168 strains from patients living in different parts of Germany. Most of the 54 German PT8 strains were similar in their stx genotypes (87% carried the stx1 and the stx2c genes) and motility (89% were NM). On the other hand, about 90% of the 48 German PT2 strains carried the stx2 gene and 98% expressed the H7 antigen. Beutin et al. (10) observed that PT2 and PT8 strains represent two distinct prevalent subclones of STEC O157:H7 which form two separate clusters by PFGE typing.

Interestingly, we have found a significant association between STEC O157:H7 PT2 stx2 strains and STEC O157:H7 PT14 strains (stx1 stx2 or stx2) and the presence of acute pathologies. STEC O157:H7 PT2 stx2-positive and stx2c-positive strains were significantly more frequently associated with HUS and bloody diarrhea in Finland (26). A close association was found between the presence of the stx2 (stx2-positive and stx2c-negative) variant gene and severe disease in infected humans in Germany (10), Holland (33), and Japan (51). Most HUS patients from those German and Dutch studies were infected with STEC O157:H7 PT2 or PT4 strains. In contrast, acute pathologies were not associated with PT8 strains in the present study or in previous studies. Forty-seven of 54 German PT8 strains were positive for the stx1 and the stx2c genes but negative for the stx2 gene. This was also the case for most PT8 strains from other countries. Recent data indicate that stx2c strains produce smaller amounts of toxin than stx2 strains. In contrast, no association could be made between the presence of the stx1 gene and severe disease in humans (10, 51; this study).

As in previous studies (45, 46, 47, 56, 58), our results provide clear evidence for the superior capability of PFGE analysis compared with that of phage typing for the discrimination of unrelated strains. The results of our study also confirm those of earlier investigations about the macrorestriction patterns of epidemiologically unrelated STEC O157:H7 strains with a high degree of similarity due to the relatively limited genetic diversity within this serotype (46). However, phage typing combined with PFGE was shown to be a highly discriminatory technique, and the high number (n = 66) of phage type-PFGE subtype combinations obtained was not surprising, as most strains were unrelated and from different sources.

Some of the PFGE types of unrelated strains could be subdivided by phage typing (for example, PFGE type 18 included PT8, PT14, and PT32). Similar results were reported by Izumiya et al. (36) in Japan, Preston et al. (56) in Canada, and Liesegang et al. (46) in Germany. Thus, Preston et al. (56) could subdivide unrelated strains with the same XbaI PFGE pattern into phage types PT1, PT8, PT14, and PT32; and the use of an additional restriction enzyme for PFGE indicated that there were genomic differences among some of those strains. These results suggest the presence of distinct genotypes among STEC O157:H7 isolates beyond that revealed by PFGE analysis with XbaI, and they provide evidence for the view that more than one restriction enzyme should be used for analysis of isolates of this serotype.

Comparing patient strains from those from asymptomatic carriers living in the same household (Table 5), we found different PFGE patterns in two cases (C11 and C6) among patients and their corresponding strains from asymptomatic carriers, although the strains showed high degrees of similarity. This was an unexpected result, and it may have been due to the fact that the patient and asymptomatic carrier strains were collected at different times, as the strains from the asymptomatic carriers were isolated 3 or 4 weeks after detection of the strains in the patients, although it could also have been due to the existence of two variants of the same strain, which could explain their different virulences. However, this is the first time that we have detected such PFGE changes. In two recently detected familiar outbreaks due to STEC O157:H7 PT8 stx1 stx2 eae-γ1 and STEC O26:H11 stx1 eae-β1, which occurred in Lugo in 2003, all patient strains and the corresponding asymptomatic carrier strains isolated showed indistinguishable PFGE patterns, supporting the utility of the PFGE fingerprinting method for the tracing of outbreaks (J. Blanco et al., unpublished data).

We agree with Liesegang et al. (46) that it is necessary to emphasize that PFGE alone appears to give rise to insufficient surveillance data. We also conclude that phage typing and PFGE fingerprinting represent complementary procedures for the subtyping of STEC O157:H7 strains, and the use of these procedures combined provides optimal discrimination. The broad range of PFGE subtypes found in this study demonstrates the natural occurrence of many genetic variants among the STEC O157:H7 strains spread throughout Spain. However, STEC O157:H7 PT2 and PT8 strains seem to form two distinct subclones which are dominant in Spain and other European countries.

Acknowledgments

We thank Monserrat Lamela for skillful technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (grants FIS G03-025-COLIRED-O157 and FIS 98/1158), the Xunta de Galicia (grant PGIDIT02BTF26101PR), the Comisión Interministerial de Ciencia y Tecnología (grants CICYT-ALI98-0616 and CICYT-FEDER-1FD1997-2181-C02-01), and the European Commission (FAIR programme grants CT98-4093 and CT98-3935). A. Mora and G. Dahbi acknowledge the Xunta de Galicia and the Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional (AECI) for research fellowships.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adu-Bobie, J., G. Frankel, C. Bain, A. G. Goncalves, L. R. Trabulsi, G. Douce, S. Knutton, and G. Dougan. 1998. Detection of intimins α, β, γ, and δ, four intimin derivatives expressed by attaching and effacing microbial pathogens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:662-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed, R., C. Bopp, A. Borcyzk, and S. Kasatiya. 1987. Phage typing scheme for Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Infect. Dis. 155:806-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed, R., A. Ali, W. Demczuk, D. Woodward, C. Clark, R. Khakria, and F. Rodgers. 2001. Emergence of new molecular and phage typing variants of E. coli O157:H7 in Canada, p. 123. In G. Duffy, P. Garvey, J. Coia, Y. Wasteson, and D. A. McDowell (ed.), Verocytotoxigenic E. coli in Europe, vol. 5. Epidemiology of verocytotoxigenic E. coli. Concerted action CT98-3935. Teagasc, The National Food Centre, Dublin, Ireland. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akiba, M., T. Masuda, T. Sameshima, and K. Katsuda. 1999. Molecular typing of Escherichia coli O157:H7 (H−) isolates from cattle in Japan. Epidemiol. Infect. 122:337-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allison, L., A. Stirrat, and F. M. Thomson-Carter. 1998. Genetic heterogeneity of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in Scotland and its utility in strain subtyping. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:844-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allison, L. J., P. E. Carter, and F. M. Thomson-Carter. 2000. Characterization of a recurrent clonal type of Escherichia coli O157:H7 causing major outbreaks of infection in Scotland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1632-1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avery, S. M., E. Liebana, M. L. Hutchison, and S. Buncic. 2004. Pulsed field gel electrophoresis of related Escherichia coli O157 isolates associated with beef cattle and comparison with unrelated isolates from animals, meats and humans. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 92:161-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banatvala, N. P., M. Griffin, K. D. Greene, T. J. Barrett, W. F. Bibb, J. H. Green, J. G. Wells, and the Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Study Collaborators. 2001. The United States National Prospective Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Study: microbiologic, serologic, clinical, and epidemiologic findings. J. Infect. Dis. 183:1063-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beutin, L., S. Zimmermann, and K. Gleier. 1996. Rapid detection and isolation of Shiga-like toxin (verocytotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli by direct testing of individual enterohemolytic colonies from washed sheep blood agar plates in the VTEC-RPLA assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:2812-2814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beutin, L., S. Kaulfuss, T. Cheasty, B. Brandenburg, S. Zimmermann, K. Gleier, G. A. Willshaw, and H. R. Smith. 2002. Characteristics and association with disease of two major subclones of Shiga toxin (verocytotoxin)-producing strains of Escherichia coli (STEC) O157 that are present among isolates from patients in Germany. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 44:337-346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beutin, L., G. Krause, S. Zimmermann, S. Kaulfuss, and K. Gleier. 2004. Charaterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from human patients in Germany over a 3-year period. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1099-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blanco, J., E. A. González, S. Garcia, M. Blanco, B. Regueiro, and I. Bernárdez. 1988. Production of toxins by Escherichia coli strains isolated from calves with diarrhoea in Galicia (north-western Spain). Vet. Microbiol. 18:297-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanco, J., M. Blanco, J. E. Blanco, A. Mora, M. P. Alonso, E. A. González, and M. I. Bernárdez. 2001. Epidemiology of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli (VTEC) in ruminants, p. 113-148. In G. Duffy, P. Garvey, and D. McDowell (ed.), Verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Food & Nutrition Press Inc., Trumbull, Conn.

- 14.Blanco, J. E., M. Blanco, A. Gutiérrez, C. Prado, M. Rio, L. Fernández, M. J. Fernández, V. Saínz, and J. Blanco. 1996. Detection of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in ground beef using immunomagnetic separation. Microbiol. SEM 12:385-394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blanco, J. E., M. Blanco, M. P. Alonso, A. Mora, G. Dahbi, M. A. Coira, and J. Blanco. 2004. Serotypes, virulence genes and intimin types of Shiga toxin (verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from human patients: prevalence in Lugo (Spain) from 1992 through 1999. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:311-319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanco, M., J. E. Blanco, J. Blanco, E. A. González, A. Mora, C. Prado, L. Fernández, M. Rio, J. Ramos, and M. P. Alonso. 1996. Prevalence and characteristics of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 and other verotoxin-producing E. coli in healthy cattle. Epidemiol. Infect. 117:251-257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanco, M., J. E. Blanco, A. Mora, J. Rey, J. M. Alonso, M. Hermoso, J. Hermoso, M. P. Alonso, G. Dhabi, E. A. González, M. I. Bernárdez, and J. Blanco. 2003. Serotypes, virulence genes, and intimin types of Shiga toxin (verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from healthy sheep in Spain. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1351-1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanco, M., J. E. Blanco, A. Mora, G. Dahbi, M. P. Alonso, E. A. González, M. I. Bernárdez, and J. Blanco. 2004. Serotypes, virulence genes and intimin types of Shiga toxin (Verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from cattle in Spain: identification of a new intimin variant gene (eae-ξ). J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:645-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrne, C. M., I. Erol, J. E. Call, C. W. Saspar, D. R. Buege, C. J. Hiemke, P. J. Fedorka-Cray, A. K. Benson, F. M. Wallace, and J. B. Luchansky. 2003. Characterization of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from downer and healthy dairy cattle in the upper Midwest region of the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:4683-4688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caprioli, A., S. Morabito, F. Minelli, M. L. Marziano, S. Gorietti, T. Pichiorri, and A. E. Tozzi. 2001. From Italy. VTEC infections, 1988-2000. Notiz. Ist. Superiore Sanitá 14:S1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chapman, P. A., and A. Siddons. 1996. A comparison of immunomagnetic separation and direct culture for the isolation of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 from cases of bloody diarrhoea, non-bloody diarrhoea and asymptomatic contacts. J. Med. Microbiol. 44:267-271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chapman, P. A., C. A. Siddons, A. T. Cerdan Malo, and M. A. Harkin. 1997. A 1-year study of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cattle, sheep, pigs and poultry. Epidemiol. Infect. 119:245-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chapman, P. A., A. T. Cerdán Malo, M. Ellin, R. Ashton, and M. A. Harkin. 2001. Escherichia coli O157 in cattle and sheep at slaughter, on beef and lamb carcasses and in raw beef and lamb products in South Yorkshire, UK. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 64:139-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis, M. A., D. D. Hancock, T. E. Besser, and D. R. Call. 2003. Evaluation of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as a tool for determining the degree of genetic relatedness between strains of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1843-1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desmarchelier, P. M., S. S. Bilge, N. Fegan, L. Mills, J. C. Vary, Jr., and P. I. Tarr. 1998. A PCR specific for Escherichia coli O157 based on the rfb locus encoding O157 lipopolysaccharide. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:1801-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eklund, M., K. Leino, and A. Siitonen. 2002. Clinical Escherichia coli strains carrying stx genes: stx variants and stx-positive virulence profiles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4585-4593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gannon, V. P., S. D′Souza, T. Graham, R. K. King, K. Rahn, and S. Read. 1997. Use of the flagellar H7 gene as a target in multiplex PCR assays and improved specificity in identification of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:656-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gautom, R. K. 1997. Rapid pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocol for typing of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other gram-negative organisms in 1 day. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:2977-2980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giammanco, G. M., S. Pignato, F. Grimont, P. A. D. Grimont, A. Caprioli, S. Morabito, and G. Giammanco. 2002. Characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolated in Italy and in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4619-4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grif, K., H. Karch, C. Schneider, F. D. Daschner, L. Beutin, T. Cheasty, H. Smith, B. Rowe, M. P. Dierich, and F. Allerberger. 1998. Comparative study of five different techniques for epidemiological typing of Escherichia coli O157. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 32:165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guinée, P. A. M., W. H. Jansen, T. Wadström, and R. Sellwood. 1981. Escherichia coli associated with neonatal diarrhoea in piglets and calves. Curr. Top. Vet. Anim. Sci. 13:126-162. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayes, P. S., K. Blom, P. Feng, J. Lewis, N. A. Strockbine, and B. S. Swaminathan. 1995. Isolation and characterization of a β-d-glucuronidase-producing strain of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the United States. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:3347-3348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heuvelink, A. E., N. C. Van de Kar, J. F. Meis, L. A. Monnens, and W. J. Melchers. 1995. Characterization of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 isolates from patients with haemolytic uraemic syndrome in Western Europe. Epidemiol. Infect. 115:1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heuvelink, A. E., F. L. A. M. Van Den Biggelaar, E. de Boer, R. G. Herbes, W. J. G. Melchers, J. H. J. Huis In't Veld, and L. A. H. Monnens. 1998. Isolation and characterization of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 strains from Dutch cattle and sheep. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:878-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heuvelink, A. E., F. L. A. M. Van Den Biggelaar, J. T. M. Zwartkruis-Nahuis, R. G. Herbes, R. Huyben, N. Nagelkerke, W. J. G. Melchers, L. A. H. Monnens, and E. De Boer. 1998. Occurrence of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 on Dutch dairy farms. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3480-3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Izumiya, H., T. Masuda, R. Ahmed, R. Khakhria, A. Wada, J. K. Terajima, K. Itoh, W. M. Johnson, H. Konuma, K. Shinagawa, K. Tamura, and H. Watanabe. 1998. Combined use of bacteriophage typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis in the epidemiological analysis of Japanese isolates of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Microbiol. Immunol. 42:515-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaper, J. B., S. Elliott, V. Sperandio, N. T. Perna, G. F. Mayhew, and F. R. Blattner. 1998. Attaching and effacing intestinal histopathology and the locus of enterocyte effacement, p. 163-182. In J. B. Kaper and A. D. O'Brien (ed.), Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 38.Karch, H., and M. Bielaszewska. 2001. Sorbitol-fermenting Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H− strains: epidemiology, phenotypic and molecular characteristics, and microbiological diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:2043-2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karmali, M. A. 1989. Infection by verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2:5-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kehl, S. C. 2002. Role of the laboratory in the diagnosis of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:2711-2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Keskimäki, M., M. Saari, T. Heiskanen, and A. Siitonen. 1998. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in Finland from 1990 through 1997: prevalence and characteristics of isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:3641-3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khakria, R., D. Duck, and H. Lior. 1990. Extended phage-typing scheme for Escherichia coli O157:H7. Epidemiol. Infect. 105:511-520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krause, U., F. M. Thomson-Carter, and T. H. Pennington. 1996. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157:H7 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and comparison with that by bacteriophage typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34:959-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lahti, E., M. Eklund, P. Ruutu, A. Siitonen, L. Rantala, P. Nuorti, and T. Honkanen-Buzalski. 2002. Use of phenotyping and genotyping to verify transmission of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from dairy farms. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21:189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liebana, E., R. P. Smith, E. Lindsay, I. McLaren, C. Cassar, F. A. Clifton-Hadley, and G. A. Paiba. 2003. Genetic diversity among Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolates from bovines living on farms in England and Wales. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:3857-3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liesegang, A., U. Sachse, R. Prager, H. Claus, H. Steinrück, S. Aleksic, W. Rabsch, W. Voigt, A. Fruth, H. Karch, J. Bockemühl, and H. Tschäpe. 2000. A clonal diversity of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157:H7/H− in Germany—a ten-year study. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 290:269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Louie, M., S. Read, L. Louie, K. Ziebell, K. Rahn, A. Borczyk, and H. Lior. 1999. Molecular typing methods to investigate transmission of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from cattle to humans. Epidemiol. Infect. 23:17-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mora, A. 2002. Escherichia coli verotoxigénicos (ECVT) O157:H7 y no O157. Prevalencia, serotipos, fagotipos, genes de virulencia, tipos de intiminas, perfiles de PFGE y resistencia a antibióticos de ECVT de origen humano y animal. Ph.D. thesis. Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Lugo, Spain.

- 49.Muinesa, M., M. de Simon, G. Prats, D. Ferrer, H. Pañella, and J. Jofre. 2003. Shiga toxin 2-converting bacteriophages associated with clonal variability in Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains of human origin isolated from a single outbreak. Infect. Immun. 71:4554-4562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nagano, H., T. Okui, O. Fujiwara, Y. Uchiyama, N. Tamate, H. Kumada, Y. Morimoto, and S. Yano. 2002. Clonal structure of Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing and β-d-glucuronidase-positive Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains isolated from outbreaks and sporadic cases in Hokkaido, Japan. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:405-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nishikawa, Y., Z. Zhou, A. Hase, J. Ogasawara, H. Cheasty, and K. Haruki. 2000. Relationship of genetic type of Shiga toxin to manifestation of bloody diarrhea due to enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli serogroup O157 isolates in Osaka City, Japan. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2440-2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oswald, E., H. Schmidt, S. Morabito, H. Karch, O. Marchès, and A. Caprioli. 2000. Typing of intimin genes in human and animal enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: characterization of a new intimin variant. Infect. Immun. 68:64-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paton, J. C., and A. W. Paton. 1998. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11:450-479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pebody, R. G., C. Furtado, A. Rojas, N. McCarthy, G. Nylen, P. Ruutu, T. Leino, R. Chalmers, B. de Jong, M. Donnelly, I. Fisher, C. Gilham, L. Graverson, T. Cheasty, G. Willshaw, M. Navarro, R. Salmon, P. Leinikki, P. Wall, and C. Bartlett. 1999. An international outbreak of Vero cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 infection among tourists; a challenge for the European infectious disease surveillance network. Epidemiol. Infect. 123:217-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Prats, G., C. Frías, N. Margall, T. Llovet, L. Gaztelurrutia, R. Elcuaz, A. Canut, R. M. Bartolomé, L. Torroba, Y. Dorronsoro, J. Blanco, M. Blanco, N. Rabella, P. Coll, and B. Mirellis. 1996. Colitis hemorrágica por Escherichia coli verotoxigénica. Presentación de 9 casos. Enferm. Infec. Microbiol. Clin. 14:7-15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Preston, M. A., W. Johson, R. Khakhria, and A. Borczyk. 2000. Epidemiologic subtyping of Escherichia coli serogroup O157 strains isolated in Ontario by phage typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2366-2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rey, J., J. E. Blanco, M. Blanco, A. Mora, G. Dahbi, J. M. Alonso, M. Hermoso, J. Hermoso, M. P. Alonso, M. A. Usera, E. A. Gonzalez, M. I. Bernardez, and J. Blanco. 2003. Serotypes, phage types and virulence genes of Shiga-producing Escherichia coli isolated from sheep in Spain. Vet. Microbiol. 94:47-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saari, M., T. Cheasty, K. Leino, and A. Siitonen. 2001. Phage types and genotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 in Finland. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1140-1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt, H., L. Beutin, and H. Karch. 1995. Molecular analysis of the plasmid-encoded hemolysin of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL 933. Infect. Immun. 66:1055-1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Slutsker, L., A. A. Ries, K. D. Greene, J. G. Wells, L. Hutwagner, and P. M. Griffin. 1997. Escherichia coli O157:H7 diarrhea in the United States: clinical and epidemiologic features. Ann. Intern. Med. 126:505-513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Swaminathan, B., T. J. Barret, S. B. Hunter, R. V. Tauxe, and the CDC PulseNet Task Force. 2001. PulseNet: the molecular subtyping network for foodborne bacterial disease surveillance, United States. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 7:382-389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tarr, P. I., T. E. Besser, D. D. Hancock, W. E. Keene, and M. Goldoft. 1997. Verotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection: U.S. overview. J. Food Prot. 60:1466-1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tenover, F. C., R. D. Arbeit, R. V. Goering, P. A. Mickelsen, B. E. Murray, D. H. Persing, and B. Swaminathan. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thomson-Carter, F. M., P. E. Carter, and T. H. Pennington. 1993. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis for the analysis of bacterial populations, p. 251-264. In R. G. Kroll, A. Gilmour, and M. Sussman (ed.), New techniques in food and beverage microbiology. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 65.Todd, W. T. A., and S. Dundas. 2001. The management of VTEC O157 infection. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 66:103-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Duynhoven, Y. T. H. P., C. M. de Pager, A. E. Heuvelink, W. K. van der Zwaluw, H. M. E. Maas, W. van Pelt, and W. J. B. Wannet. 2002. Enhanced laboratory-based surveillance of Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 in The Netherlands. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21:513-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wilson, J. B., R. P. Johnson, R. C. Clarke, K. Rahn, S. A. Renwick, D. Alves, M. A. Karmali, P. Michel, E. Orrbine, and J. S. Spika. 1997. Canadian perspectives on verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infection. J. Food Prot. 60:1451-1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang, W. L., B. Köhler, E. Oswald, L. Beutin, H. Karch, S. Morabito, A. Caprioli, S. Suerbaum, and H. Schmidt. 2002. Genetic diversity of intimin genes of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:4486-4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]