Abstract

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) infect keratinocytes of skin and mucosa. Homeostasis of these constantly renewing, stratified epithelia is maintained by balanced keratinocyte proliferation and terminal differentiation. Instructions from the extracellular matrix engaging integrins strongly regulate these keratinocyte functions. The papillomavirus life cycle parallels the differentiation program of stratified epithelia, and viral progeny is produced only in terminally differentiating keratinocytes. Whereas papillomavirus oncoproteins can inhibit keratinocyte differentiation, the viral transcription factor E2 seems to counterbalance the impact of oncoproteins. In this study we show that high expression of HPV type 8 (HPV8) E2 in cultured primary keratinocytes leads to strong down-regulation of β4-integrin expression levels, partial reduction of β1-integrin, and detachment of transfected keratinocytes from underlying structures. Unlike HPV18 E2-expressing keratinocytes, HPV8 E2 transfectants did not primarily undergo apoptosis. HPV8 E2 partially suppressed β4-integrin promoter activity by binding to a specific E2 binding site leading to displacement of at least one cellular DNA binding factor. To our knowledge, we show for the first time that specific E2 binding contributes to regulation of a cellular promoter. In vivo, decreased β4-integrin expression is associated with detachment of keratinocytes from the underlying basement membrane and their egress from the basal to suprabasal layers. In papillomavirus disease, β4-integrin down-regulation in keratinocytes with higher E2 expression may push virally infected cells into the transit-amplifying compartment and ensure their commitment to the differentiation process required for virus replication.

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) infect keratinocytes of skin or mucosa, leading to the induction of proliferative lesions. They play a key role in anogenital cancer, head and neck cancer, and squamous cell skin carcinomas arising in patients suffering from epidermodysplasia verruciformis (EV), a rare genetic disease. Recently, it has been shown also in immunocompetent individuals that seroreactivity to the cutaneous high-risk EV-associated HPV type 8 (HPV8) is correlated with a significantly higher risk for nonmelanoma skin cancer (11, 26).

HPV infection targets basal keratinocytes in stratified epithelia. A balanced keratinocyte proliferation rate and terminal differentiation maintain homeostasis of these constantly renewing tissues. Both proliferation and differentiation are strongly regulated by instructive signals from the underlying extracellular matrix. These signals are conveyed to the cells by integrins. Three major keratinocyte integrins, α2β1, α3β1, and α6β4, have been defined (summarized in references 2, 45, and 48). While the α2β1 and α3β1 integrins are localized to focal contacts at apicolateral surfaces of basal keratinocytes, α6β4 integrins are unique and atypical in that they do not localize to focal contacts like most other integrins (in particular β1-integrins). Rather, they localize to hemidesmosome-like structures. The morphologies of focal contacts and hemidesmosome-like structures are quite different. The first appear as thin elongated structures at the tips of actin stress fibers, while the second appear as large patches organized in ring-like structures underneath the cells. The first are connected to actin stress fibers, and the second connect intermediate filaments to the underlying extracellular matrix component laminin-5 (4, 15, 25, 44). The anchorage of keratinocytes to extracellular matrix suppresses keratinocyte differentiation (1, 24, 49). Conversely, loss of anchorage in vitro withdraws keratinocytes from the cell cycle and is thought to initiate terminal differentiation (16).

The papillomavirus life cycle parallels the differentiation program of stratified epithelia, and viruses are produced only in terminally differentiating keratinocytes. In basal cells the early viral genes are weakly expressed, and only maintenance copy numbers of the viral genome are established. Since HPV lacks a viral polymerase for vegetative DNA replication, the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 interfere with cell cycle control factors and ensure cellular DNA polymerase activity also in suprabasal keratinocyte layers, thus delaying terminal keratinocyte differentiation (29, 34, 35, 51). The viral transcription factor E2 plays a major role in viral transcription and the initiation of viral replication. It consists of an N-terminal transactivation domain and a C-terminal dimerization and DNA binding domain which recognizes the ACCN6GGT sequence motif. E2 is expressed at only low levels in basal keratinocytes. In HPV16-positive cervical intraepithelial neoplasia I and II lesions, E2 is found mainly in suprabasal layers, whereas in squamous cell carcinomas, the E2 function is mostly lost (40). HPV5 E2-specific mRNA was detected mainly in the upper two-thirds of the epidermis in a benign cutaneous lesion of a patient suffering from EV (19). It is still unclear how low E2 expression is regulated in basal keratinocytes and high E2 expression is induced in suprabasal cell layers.

The E2 protein seems to counterbalance the impact of oncoproteins on keratinocyte function. It negatively regulates the promoters for E6/E7 gene expression of genital papillomaviruses. Repression appears to be mediated by displacing cellular factors from the viral promoter (9, 43). E2 proteins from genital high-risk HPV or bovine papillomavirus induce G1 cell cycle arrest, senescence, or apoptosis in HPV-positive cells (7, 8, 20, 50). Moreover, E2 proteins from different HPVs cooperate with cellular transcription factors involved in keratinocyte differentiation. These include C/EBP factors, p300, and p53 (17, 23, 27, 28, 32). It has recently been demonstrated that the E2 protein of the genital high-risk virus HPV18 even induces apoptosis in primary keratinocytes lacking other viral proteins (6).

In line with these observations, our own attempts to establish a continuously growing cell line expressing E2 of the cutaneous high-risk virus HPV8 have repeatedly failed (S. Smola-Hess, unpublished data). We were therefore interested in investigating the consequences of HPV8 E2 expression in keratinocytes in comparison with those of HPV18 E2.

Here we show that primary keratinocytes expressing the E2 protein of the EV-associated cutaneous high-risk HPV8 do not primarily undergo apoptosis, as is observed for HPV18 E2. High expression of HPV8 E2 led to strong down-regulation of the β4-integrin and detachment of transfected keratinocytes from underlying structures in vitro. E2 partially suppressed β4-integrin promoter activity by specifically binding to a low-affinity E2 binding site, leading to displacement of at least one cellular DNA binding factor. To our knowledge, we show for the first time that specific E2 binding contributes to regulation of a cellular promoter.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs.

The expression constructs pEYFP-HPV8-E2 and pEYFP-HPV18-E2, encoding full-length E2 fusion proteins, and pEYFP-HPV8-E2C, encoding enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) fused to the DNA binding and dimerization domain of HPV8 E2, have previously been described (17). The L5.5K luciferase reporter construct containing a fragment (−5197 to +333) of the human β4-integrin promoter region fused upstream of the firefly luciferase gene in the pGL3-basic vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.) was a generous gift from S. Hirohashi (42). L5.5K-BS-II-mut was constructed by using the QuickChange XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Ten nanograms of plasmid template L5.5K and 125 ng of primers containing three single-nucleotide mismatches (underlined) in the putative E2 binding site II (BS-II-mut) (5′-GCAGAACAGCTCTCAGATGGCGAGGAAAGGCGGCGACTCACAC-3′ [the positions of the E2 consensus binding site are shown in boldface]) were incubated in a final volume of 50 μl for mutagenesis. Sequencing confirmed the incorporated mutations.

Cell culture and transfection.

Primary human foreskin keratinocytes (HFKs) (BioWhittaker, Vervier, Belgium) were cultured under low-calcium (0.15 mM) conditions in KGM-2 medium (BioWhittaker) containing insulin, epidermal growth factor, hydrocortisone, epinephrine, and bovine pituitary extract according to the supplier's instructions. Second- to fourth-passage keratinocyte cultures were seeded at a density of 3.7 × 104 cells/cm2. Twenty-four hours later a total amount of 0.2 μg of DNA/cm2 was transfected with TransFast transfection reagent (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cells were analyzed 24 to 48 h after transfection. All experiments were performed at least three times, with keratinocytes from three different donors. Nuclear extracts were isolated as described by Schreiber et al. (37).

293T cells (31) were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (with Glutamax I) supplemented with 8% fetal calf serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 0.1 mg of streptomycin per ml, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (all from Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany). For transfection, FuGene6 transfection reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, Ind.) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 293T cells were plated in 15-cm-diameter tissue culture dishes at 8.7 × 106 cells per dish and grown for 24 h prior to the addition of 70 μg of pEYFP-C1 or pEYFP-HPV8-E2C DNA. After 48 h, nuclear extracts were isolated.

Detachment assay.

To quantify the detachment of transfected HFKs from the culture dish, floating cells were collected from the supernatants 48 h after transfection, centrifuged, and resuspended in 50 μl of culture medium. The numbers of EYFP-positive and -negative cells were counted by using a Neubauer chamber under a fluorescence microscope (Axiovert 135; Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Transfection efficiencies were determined by counting pooled adherent and nonadherent cells. The numbers of EYFP-positive cells in the supernatants were normalized to the respective transfection efficiencies. Results from transfections containing only pEYFP-C1 were set as the reference (value of 1). Experiments were performed twice in quadruplicate.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

HFKs were grown on glass coverslips and transfected with pEYFP-HPV8-E2, pEYFP-HPV18-E2, or pEYFP-C1 control vector, with maximum transfection efficiencies of 4 to 5% for the E2 expression constructs and 8% for the control vector. At 48 h after transfection, cells were washed (leading to a further loss of E2-transfected cells), fixed with 2% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min, and permeabilized in 0.2% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 for 1 min. Cells were rinsed three times with PBS and incubated in 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 45 min, followed by a 1-h incubation with primary anti-human β4-integrin antibody (3E1, murine immunoglobulin G1 [mIgG1]) (Chemicon, Temecula, Calif.) diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer (2% BSA-PBS). After washing six times with PBS, Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, Pa.) diluted 1:400 in blocking buffer was applied for another 45 min together with a solution of 1 μg of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) per ml for nuclear staining. F-actin was labeled with phalloidin AlexaFluor 633 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.), using 3 U per coverslip, according to the manufacturer's protocol. All steps were performed at room temperature. After washing six times with PBS, coverslips were mounted on microscope slides with Aquatex (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and visualized with a Leica TCS-NT confocal laser scanning microscope or a Nikon fluorescence microscope. In the case of β4-integrin staining, all pictures were recorded at the focal plane corresponding to the cell-substrate interface. In some experiments analyzed with the latter microscope, strong EYFP expression was also seen with the filters for Cy3 detection.

Cell staining and flow cytometry.

HFKs were harvested 48 h after transfection, resuspended in blocking buffer, and centrifuged. Cells (4 × 105) were incubated with anti-β4-integrin antibodies diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer or hybridoma supernatant containing anti-β1-integrin (P5D2, mIgG1) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa) or anti-major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I (W6/32, mIgG2a) (ATCC HB-95) antibodies for 45 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed, stained with allophycocyanin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (BD PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) for 45 min at 4°C, and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde. Flow cytometry analysis was performed with a FACSCalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). Control experiments were carried out with isotype-matched antibodies. Mean fluorescence intensities were calculated with the CellQuest program (Becton Dickinson).

Luciferase assay.

Cell lysis and luciferase quantifications were performed 48 h after transfection. The cells were washed twice in PBS and lysed by adding 300 μl of luciferase extraction buffer containing 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) and 0.5% NP-40. Luciferase activity was determined with a Berthold (Wildbad, Germany) luminometer and normalized to protein concentrations in the respective extracts. Mean values ± standard deviations from three experiments with triplicate determinations each were calculated.

EMSA.

Double-stranded synthetic oligonucleotides were synthesized as follows: BS-I, CTTAGTGAGACCTCCCTGGGTTGACATCTCGCC (nucleotides [nt] 3133 to 3144); BS-II, TCTCAGATGACCAGGAAAGGTGGCGACTCACAC (nt 3590 to 3601); BS-III, CTGCTATGCACCAGGCATGGTGCTAGGTGCTAG (nt 3753 to 3764); BS-II-mut, TCTCAGATGGCGAGGAAAGGCGGCGACTCACAC; and HPV18 control E2-BS, CGGTCGGGACCGAAAACGGTGTATATAAA (nt 50 to 78). (Numbering for BS-I to -III is according to GenBank accession number AB012286; consensus binding sites are shown in boldface, and point mutations introduced into the consensus binding sites are underlined. HPV18 E2-1 represents the first E2 binding site within the HPV18 long control region [accession number AY262282].) For electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) oligonucleotides were labeled with [α-32P]dATP by using Klenow fragment (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Nuclear extracts prepared from transfected 293T cells or untransfected HFKs were incubated with 32P-labeled DNA probe in the presence of 20 mM HEPES-K (pH 7.9), 60 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM spermidine, 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mg of BSA per ml, 50 μg of poly(dI-dC) (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) per ml, 10% glycerol, 1.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 0.3 μg of aprotinin (Sigma) per μl in a final volume of 30 μl on ice for 30 min. Reaction products were then separated in a 5% polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA. The gels were dried and exposed to autoradiographic films.

For supershift experiments, anti-EYFP polyclonal rabbit antibody (BD Biosciences Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) was used at dilutions of 1:5, 1:10, 1:20, and 1:40. Baculovirus-generated His-tagged HPV8-E2 (41) was used in competition assays.

RESULTS

HPV8 E2- and HPV18 E2-transfected primary keratinocytes detach from culture dishes.

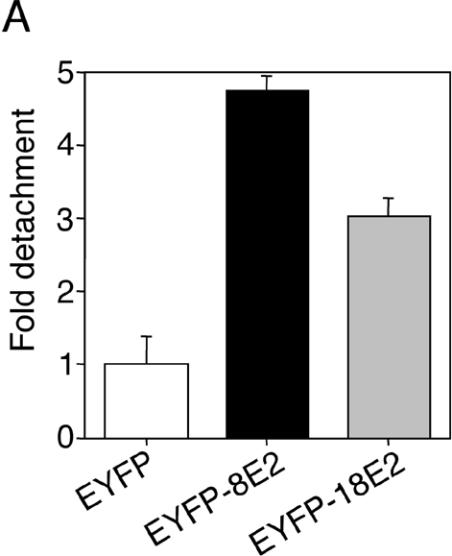

In order to identify E2-positive cells under the fluorescence microscope, expression vectors encoding full-length E2 from HPV8 or HPV18 fused to EYFP were used for transfection of primary human keratinocytes. These fusion proteins were transcriptionally active, since they were both able to activate an E2-dependent luciferase reporter construct (data not shown). We observed that E2-expressing cells displayed a greater tendency to detach spontaneously from culture dishes compared with transfection controls. This effect was noticeable already at 24 h posttransfection and progressed during the next 24 h. To quantify detachment, the number of EYFP-positive cells among floating cells was counted and normalized to transfection efficiency in each group. Detachment of HPV8 E2-expressing primary keratinocytes was about fivefold higher, and detachment of HPV18 E2-expressing cells was threefold higher, than that of controls expressing only EYFP (Fig. 1A).

FIG. 1.

(A) Detachment of HPV E2-expressing keratinocytes from culture dish. Primary human keratinocytes were seeded in 12-well plates and transfected with 0.77 μg of pEYFP-C1, pEYFP-HPV8-E2, or pEYFP-HPV18-E2 expression construct. After 48 h, the number of fluorescent cells floating in the supernatants was counted. The data were normalized to the transfection efficiencies in each group. Shown is the relative detachment compared with the EYFP control in two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) HPV E2-expressing keratinocytes display distinct morphological features. Keratinocytes seeded on glass coverslips were transfected as described above. After 48 h, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with AlexaFluor-633-phalloidin (red fluorescence) and DAPI (blue fluorescence). EYFP- or EYFP-E2-expressing cells (two independent stainings) (green fluorescence) were analyzed by confocal microscopy. Overlays are shown in the right panels. (C) HPV E2-expressing keratinocytes can be found on top of nontransfected cells. Keratinocytes transfected with pEYFP-HPV8-E2 and stained as described above were analyzed by confocal microscopy (left panel). A section (gray line) through a nontransfected cell (right cell, nucleus in blue) and an EYFP-HPV8 E2-expressing cell lying above (left cell, nucleus in blue with EYFP-fluorescence in green) is shown in the right panel.

To characterize the potential morphological changes of E2-expressing keratinocytes, adherent cells were stained with phalloidin. Confocal microscopy analysis of F-actin staining revealed pronounced changes in the morphology of the actin skeleton of E2-transfected cells. The cells displayed loss of cell-cell contacts and rounded up. These changes were accompanied by a considerable reduction in cell size, particularly in HPV18 E2-expressing keratinocytes (Fig. 1B). Phalloidin staining of control EYFP-positive cells revealed a typical distribution of actin filaments for normal keratinocytes and did not display any differences compared with surrounding untransfected cells.

HPV18 E2 but not HPV8 E2 induces apoptosis in primary keratinocytes.

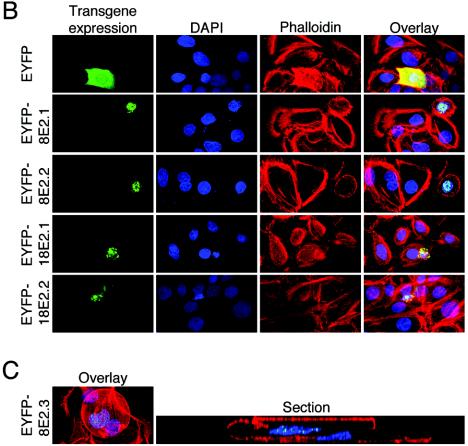

Increased detachment of HPV8 E2-positive cells might be a result of apoptosis, as previously demonstrated for HPV18 E2. To address this question, we analyzed DAPI-stained nuclei of E2-expressing cells under the fluorescence microscope. Primary human keratinocytes expressing EYFP or treated with staurosporine, an apoptosis-inducing agent, served as controls. Staurosporine-treated cells revealed nuclear fragmentation in most examined cells (Fig. 2, column 2). Characteristic chromatin condensation or nuclear fragmentation was also consistently observed in the nuclei of HPV18 E2-expressing cells. In contrast to these cells, keratinocytes transfected with pEYFP-HPV8-E2 or with pEYFP-C1 vector alone did not display any signs of nuclear fragmentation (Fig. 1 and 2, second columns). Interestingly, HPV8 E2-positive cells were found on top of nontransfected cells. One example is documented in Fig. 1C.

FIG. 2.

HPV18- and HPV8 E2-expressing keratinocytes both lose β4-integrin expression, but only HPV18 E2-positive cells display apoptotic nuclei. Primary human keratinocytes were seeded in 24-well plates; transfected with 0.4 μg of pEYFP-C1, pEYFP-HPV8-E2, or pEYFP-HPV18-E2 expression constructs (green fluorescence); fixed; permeabilized after 36 h; and stained with DAPI (blue fluorescence) and anti-β4-integrin primary antibody and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (red fluorescence). The overlays are shown in the right panel. Due to low transfection efficiencies of the pEYFP-E2 constructs, only single cells could be recorded at a 400-fold magnification. EYFP-8E2.1 to -3 represent the results from three independent pEYFP-HPV8-E2 transfections. The lower panels represent untransfected cells treated with 1 μM staurosporine for 5 h as a control.

β4-integrin expression is down-regulated in HPV8 E2-transfected keratinocytes.

Since induction of apoptosis did obviously not account for HPV8 E2-mediated cell detachment, we analyzed integrin expression mediating cellular adhesion. In fact, E2-transfected cells displayed low or absent β4-integrin expression as judged from immunocytochemistry (Fig. 2, column 3). Reduction of β4-integrin expression was observed in HPV8 E2- as well as HPV18 E2-expressing cells, irrespective of signs of nuclear fragmentation. β4-integrin expression levels remained unchanged in controls expressing EYFP alone and were largely unaffected in staurosporine-treated apoptotic cells. These data revealed that apoptosis in normal human keratinocytes was not necessarily associated with down-regulation of β4-integrin. Rather, down-regulation of β4-integrin seemed to be specific for E2-induced cellular changes. To avoid any interference with apoptosis mechanisms, we continued the following experiments with the HPV8 E2 protein only.

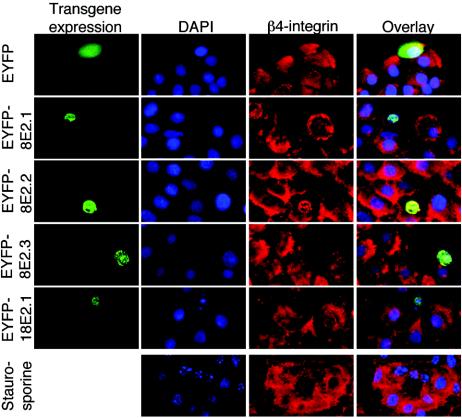

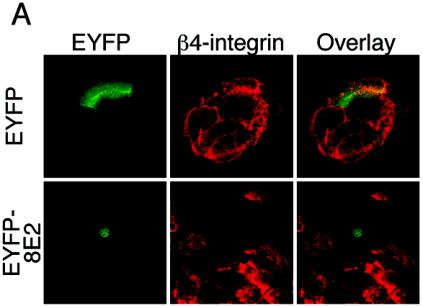

Confocal microscope pictures recorded at the focal plane corresponding to the cell-substrate interface showed large patches distributed underneath the cells, typical of β4-integrins, in nontransfected and in pEYFP-transfected cells (Fig. 3A, upper panels). The staining for β4-integrin was strongly reduced in the pEYFP-HPV8-E2-transfected cells, confirming the observation that β4-integrin expression may even be completely lost in some keratinocytes transfected with HPV8 E2 (Fig. 3A, lower panels).

FIG. 3.

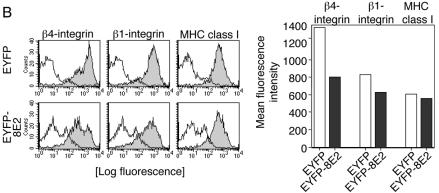

(A) Analysis of the β4-integrin expression pattern by confocal laser scanning microscopy. Keratinocytes seeded on glass coverslips were transfected with pEYFP-C1 vector or the pEYFP-HPV8-E2 or pEYFP-HPV18-E2 expression construct. After 48 h, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with anti-β4-integrin (red fluorescence) primary and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies. EYFP-expressing cells (green fluorescence) were analyzed by confocal microscopy. Overlays are shown in the right panel. All pictures of β4-integrin stainings were recorded at the focal plane corresponding to the cell-substrate interface. (B) HPV8 E2 strongly down-regulates β4-integrin compared with β1-integrin and MHC class I expression levels. Keratinocytes were seeded onto plastic dishes. After 24 h, they were transfected with expression constructs encoding EYFP or EYFP-tagged HPV8 E2. Forty-eight hours later, cells were harvested, stained, and gated for EYFP fluorescence. Expression levels of β4- and β1-integrins as well as MHC class I were determined by flow cytometry and are represented by solid gray histograms (left panels). The white histograms represent isotype-matched controls (left panels). Mean fluorescence intensities of the respective stainings are shown in the right panel.

To quantify β4-integrin expression levels further, we performed flow cytometry analysis. Keratinocytes were gated for EYFP fluorescence and analyzed for β4-integrin, β1-integrin, and MHC class I expression levels as controls. Whereas expression of MHC class I remained almost unchanged (92% expression according to mean fluorescence intensity) (Fig. 3B, right panel), HPV8 E2-positive keratinocytes showed an approximately 10-fold down-regulation of β4-integrin expression in more than 40% of the transfected cells and mild down-regulation of β1-integrin (24%) in the transfected cells (Fig. 3B).

HPV8 E2 binds to sequence-specific sites in the β4-integrin promoter with different affinities.

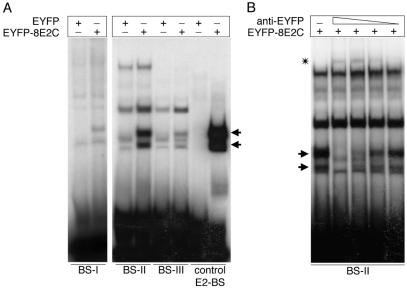

The E2 protein can suppress papillomavirus promoters by binding to low-affinity binding sites, leading to the displacement of cellular binding factors. Although no cellular promoter containing E2 binding sites has been described so far, we investigated the β4-integrin promoter (GenBank accession number AB0 12286) for E2 consensus binding sites in a computer-based search using the MatInspector program (33). Surprisingly, three potential E2 binding sites within this β4-integrin promoter region were detected: BS-I at positions 3133 to 3144, BS-II at 3590 to 3601, and BS-III at 3753 to 3764 (see Materials and Methods for the respective sequences). To test their E2 binding capacities, EMSAs were performed with the different E2 binding sites and nuclear extracts isolated from pEYFP-HPV8-E2C-transfected 293T cells expressing the HPV8 E2 DNA binding domain. An oligonucleotide comprising an E2 binding site from the HPV18 long control region served as a control. The HPV8 E2 C-terminal portion bound to all tested oligonucleotides. However, the amount of product bound varied greatly, suggesting differences in binding affinities. BS-II displayed the highest affinity among the cellular E2 binding sites, followed by BS-III, whereas binding to BS-I was almost undetectable (Fig. 4A). To visualize the specific binding of the E2 C terminus to BS-I, a fivefold-larger amount of nuclear extract was needed. Bands observed in EMSAs performed with EYFP control extracts on BS-II were also observed in parallel control EMSAs performed with untransfected 293T cells and therefore appear not to be due to EYFP expression (data not shown). Moreover, after specific supershifting of EYFP-HPV8 E2C, the same bands were still seen in EMSA, further supporting that they were independent of EYFP expression (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

(A) HPV8 E2 binds to specific sites within the β4-integrin promoter with different affinities. 32P-labeled oligonucleotides comprising a single E2 binding site (BS-II and BS-III) were incubated with 28 μg of nuclear extracts isolated from pEYFP-C1- and pEYFP-HPV8-E2C-transfected 293T cells. In reaction mixtures containing BS-I, fivefold more nuclear extract was added. Oligonucleotides comprising the first E2 binding site (control E2-BS) within the HPV18 long control region served as controls. The arrows indicate binding activities appearing in the EYFP-8E2C-containing extracts. (B) Supershift analysis of the EYFP-8E2C binding activity on BS-II. Serial dilutions (1:5, 1:10, 1:20, and 1:40) of antibodies directed against the EYFP moiety were added to the nuclear extracts isolated from 293T cells transfected with pEYFP-HPV8-E2C prior to the addition of 32P-labeled wild-type BS-II oligonucleotides. Supershifted complexes are indicated by an asterisk. Arrows indicate the EYFP-HPV8-E2C specific bands, which disappeared with increasing doses of anti-EYFP antibody.

BS-II, displaying the highest affinity for E2 among the cellular binding sites was analyzed in more detail by use of supershift experiments. Serial dilutions of anti-EYFP antibodies were added to the nuclear extracts. The EYFP-8E2C-specific band gradually disappeared with increasing doses of anti-EYFP antibody, while a novel higher-molecular-weight complex appeared (Fig. 4B). Compared to the intensity of the E2C/BS-II complex, the supershifted bands are weak. This might be due to the fact that the polyclonal anti-EYFP antibodies used for supershifting prevent proper dimerization of the E2C portion within the fusion protein, which is required for binding to the E2 binding site.

HPV8 E2 suppresses the β4-integrin promoter.

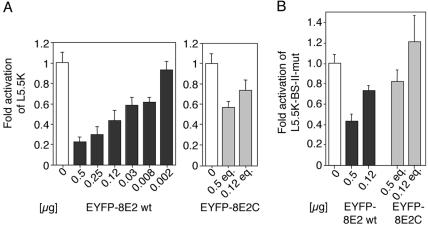

In order to investigate whether E2 exerted a direct effect on the β4-integrin promoter activity, we performed transient-transfection assays with a luciferase reporter construct (L5.5K) in primary HFKs. Cotransfection of the pEYFP-HPV8-E2 expression plasmid repressed L5.5K reporter gene activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A, left panel), which was still observed with 8 ng of pEYFP-HPV8-E2 expression plasmid. Repression was also detected in transient-transfection experiments with an expression vector encoding untagged HPV8 E2 (pcDNA-HPV8-E2) (17), ruling out effects of the EYFP tag only (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

(A) Repression of the β4-integrin promoter by wild-type HPV8 E2 (left panel) or the HPV8 E2 C terminus (right panel). Normal human keratinocytes were cotransfected with the luciferase reporter plasmid L5.5K under control of the β4-integrin promoter (1.5 μg) and decreasing amounts of pEYFP-HPV8-E2 expression plasmids or with equimolar amounts (eq.) of pEYFP-HPV8-E2C encoding the C-terminal portion of E2. The total amount of DNA was adjusted with empty pEYFP-C1 vector. (B) The E2 BS-II within the β4-integrin promoter contributes to repression by the HPV8 E2 C terminus. A β4-integrin promoter reporter construct (L5.5K-BS-II-mut) (1.5 μg) containing the same mutated BS-II as in Fig. 7A was cotransfected with pEYFP-HPV8-E2 (0.5 or 0.125 μg) or equimolar amounts of pEYFP-HPV8-E2C into HFKs. The total amount of DNA was adjusted with empty pEYFP-C1 vector. All luciferase activities were determined after 48 h and normalized with the protein concentration of the respective luciferase extracts. The value of the control (empty pEYFP-C1 vector only, open bars) was set at 1. Transfections were conducted in triplicates. The indicated values were averaged from three independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

More than 40% inhibition of L5.5K was still obtained when the HPV8 E2 carboxy-terminal portion fused to EYFP (pEYFP-HPV8-E2C) was cotransfected (Fig. 5A, right panel). This was particularly interesting, since the E2 C terminus comprises the DNA binding domain of the transcription factor.

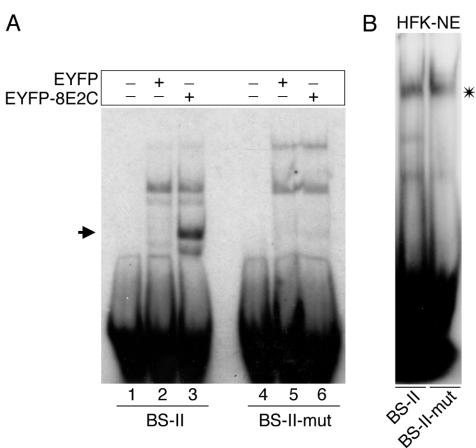

HPV8 E2 replaces a cellular factor binding to the β4-integrin promoter.

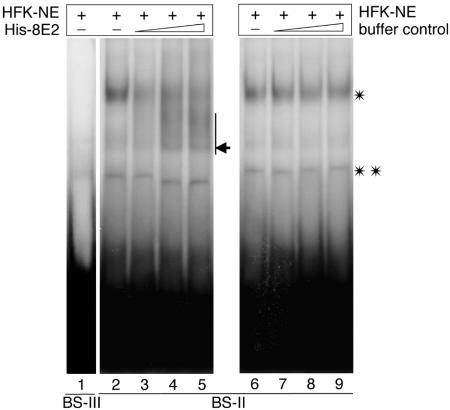

We next performed gel retardation assays in order to determine whether the binding of E2 to the β4-integrin promoter interferes with binding of potential cellular DNA binding factors present in the nuclear extracts of HFKs. At least two complexes of the oligonucleotide comprising BS-II with cellular proteins were detected by EMSA (Fig. 6, lanes 2 and 6). One of these complexes was displaced from the oligonucleotide by increasing amounts of purified baculovirus-expressed His-tagged HPV8 E2, whereas the second complex remained stable (Fig. 6, lanes 3 to 5). To exclude the possibility that the observed displacement resulted from changes in buffer composition, control EMSAs were performed. The binding of the latter cellular complex to BS-II remained unchanged when E2-dissolving buffer (without E2) was employed (Fig. 6, lanes 7 to 9). In this case, binding of the analyzed unknown cellular DNA binding factor remained unchanged. On BS-III binding, activity of cellular proteins was hardly detectable (Fig. 6, lane 1).

FIG. 6.

HPV8 E2 displaces a cellular factor binding to the BS-II of the β4-integrin promoter. Nuclear extracts prepared from HFKs (HFK-NE) were incubated with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing the BS-III (lane 1) or BS-II (lanes 2 to 9) of the β4-integrin promoter. In the case of BS-II, increasing amounts of baculovirus-expressed histidine-tagged HPV8 E2 protein (His-8E2) (lanes 3, 4, and 5) or His-8E2 elution buffer (lanes 7, 8, and 9) were added, and complexes were analyzed by EMSA. The E2-containing band is indicated by an arrow. The single and double asterisks indicate two different complexes of cellular proteins binding to the BS-II oligonucleotides.

The second E2 binding site contributes to E2-mediated suppression.

To elucidate the functional relevance of the second E2 binding site for the regulation of β4-integrin gene expression, point mutations were introduced into the BS-II sequence. These mutations (in BS-II-mut) abolished binding of the HPV8 E2 C-terminal portion (Fig. 7A, right panel) but did not prevent binding of the cellular factor(s) displaceable by E2 (Fig. 7B). Luciferase assays were again performed with primary HFKs, using an L5.5K reporter construct with corresponding mutations (L5.5K-BS-II-mut). The ability of full-length HPV8 E2 or the HPV8 E2 C terminus to repress this mutated reporter construct was reduced by 20 to 30% compared with that of the wild-type β4-integrin promoter. Suppression was completely lost in cotransfections with 0.12 μg of the pEYFP-HPV8-E2C plasmid (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 7.

(A) Mutations within the E2 BS-II of the β4-integrin promoter abolish HPV8 E2 binding. 32P-labeled oligonucleotides comprising wild-type or mutated BS-II (BS-II-mut containing the same mutated BS-II as in Fig. 5B) were incubated with 28 μg of nuclear extracts isolated from 293T cells transfected with pEYFP-C1 (lanes 2 and 5) or pEYFP-HPV8-E2 (lanes 3 and 6). Lanes 1 and 4 show the free oligonucleotide controls. (B) Mutations within the E2 BS-II of the β4-integrin promoter do not abolish binding of the E2-displaceable cellular factor (asterisk). Nuclear extracts (10 μg) prepared from HFKs were incubated with 32P-labeled oligonucleotides containing the BS-II or BS-II-mut and analyzed by EMSA.

DISCUSSION

The papillomavirus transcription factor E2 is an important regulator of viral transcription and replication. E2 is expressed at low levels in basal layers and at higher levels in suprabasal layers of HPV-infected epithelia (19, 40). Currently, it is not known how the E2 expression pattern is regulated in different layers of the epithelium, since no E2-specific promoter has been defined yet.

In HPV-infected epithelia, the viral oncoproteins keep suprabasal keratinocytes in cycle and suppress differentiation. Terminal differentiation of keratinocytes, however, is required to complete the viral life cycle. Recently, it has been shown that E2 binds to and cooperates with cellular transcription factors, which are involved in keratinocyte differentiation (17, 23, 27, 28, 32). In noninfected epithelia, differentiation is triggered by loss of integrin-mediated anchorage to extracellular matrix (1, 24, 49).

In this study we show that high expression of HPV8 E2 in cultured primary keratinocytes leads to strong down-regulation of the β4-integrin, partial reduction of β1-integrin expression, and detachment of transfected keratinocytes from underlying structures.

Detachment of keratinocytes was observed after transfection of HPV8 E2 as well as HPV18 E2. However, transfectants displayed strong differences in morphology. Our results are compatible with the hypothesis that HPV18 E2 can cause apoptosis, which was recently described by Demeret et al. (6). In contrast to this, nuclei of HPV8 E2-expressing cells remained completely intact, suggesting that apoptosis was not a prerequisite for cellular detachment. Rather, we observed that integrin expression levels decreased in HPV8 E2-expressing keratinocytes. While β1-integrin expression levels were slightly reduced, a much stronger reduction was observed for β4-integrin expression levels. Of note, β4-integrin is the major integrin required for keratinocyte attachment to the underlying matrix (for reviews, see references 2 and 5). The reduction of β4-integrin expression was seen by confocal fluorescence microscopy and quantified by flow cytometry. Keratinocytes treated with staurosporine underwent apoptosis but did not necessarily lose β4-integrin expression, further underlining that apoptosis is not always accompanied by loss of β4-integrin.

One clue to the mechanism underlying E2-mediated β4-integrin suppression came from computer-based analysis of the β4-integrin promoter, where we found three potential E2 binding sites. In EMSA, we could confirm binding of the HPV8 E2 C terminus to these sites, but with markedly different affinities. The strongest binding was observed for BS-II, followed by BS-III, whereas binding to BS-I was extremely weak. In all cases, however, E2 binding was weaker than binding to a reference E2 binding site derived from an HPV-derived control region. All E2 binding sites in the β4-integrin promoter are of the classical ACCN6GGT type. However, internal or flanking sequences may account for the differences in binding. It has been suggested that a higher number of A/T pairs in the nonconserved core region (N6) of the E2 recognition sequence is preferred for binding of HPV8 E2 in the viral promoter region (41). These requirements for E2 binding correlate very well with our data obtained with E2 binding sites from the human β4-integrin promoter. BS-II contains four A/T pairs, BS-III contains three A/T pairs, and the lowest-affinity BS-I contains two A/T pairs in the nonconserved base pairs of the E2 consensus binding site.

Due to low transfection efficiencies (<4 to 5%) of the pEYFP-HPV-E2 constructs in primary keratinocytes, we were unable to selectively prepare mRNA from E2-transfected cells in order to study β4-integrin regulation on the transcriptional level. However, transient-transfection experiments revealed that E2 was able to suppress the activity of a β4-integrin promoter construct in a dose-dependent manner. About 40% suppression of the β4-integrin promoter was also achieved with the HPV8 E2 C terminus comprising only the dimerization and DNA binding domain of the transcription factor, indicating that direct E2 binding to the promoter might be relevant for suppression. Nuclear extracts derived from primary human keratinocytes contained so-far-unknown factors binding to BS-II as shown by EMSA. This binding activity was strongly inhibited by recombinant HPV8 E2 protein. Site-directed mutagenesis of BS-II within the reporter construct revealed that this E2 binding site contributed partially (about 20 to 30%) to β4-integrin promoter suppression. Thus, E2 may partially repress the β4-integrin promoter by displacing a cellular factor(s). These findings are consistent with the observation that low-affinity E2 binding sites in the HPV8 noncoding region can mediate repression by displacement of cellular transcription factors (3, 36, 41). To our knowledge, we show for the first time that specific E2 binding can regulate a cellular promoter. In the future, it will be interesting to characterize the cellular factor(s) potentially involved in regulation of β4-integrin promoter activity.

Which additional mechanisms might contribute to E2-mediated regulation of β4-integrin expression? In transient-expression assays we cannot exclude a potential contribution of squelching to repression of the reporter construct mediated by the overexpressed full-length E2 protein. However, this would not explain the strong suppression of β4-integrin protein expression levels by E2. E2 might also utilize indirect mechanisms for suppression, apart from direct effects on the β4-integrin promoter involving binding of its C terminus to the specific E2-recognition sequence ACCN6GGT. In the epithelium, β4-integrin expression is strongly down-regulated in suprabasal differentiating keratinocytes. Recently, it has been shown that the HPV E2 protein can functionally interact with a variety of cellular factors, including C/EBPα and -β, p300, and p53 (17, 23, 27, 28, 32). These cellular factors are all involved in the regulation of keratinocyte differentiation, which may influence β4-integrin expression as well.

What could be the benefit of integrin suppression for the viral life cycle? β1-integrins are important for keratinocyte proliferation. β1-integrin levels are highest in stem cells and lower in keratinocytes of the transit-amplifying compartment, which are destined to withdraw from the cell cycle and differentiate after some divisions (18, 21, 22). The β4-integrin subunit associates with α6, and the dimer is concentrated at the basement membrane zone, where it is involved in hemidesmosome formation mediating attachment to laminin-5, the preferred ligand within the underlying matrix (38, 39). Thus, the primary function of the α6β4-integrin is considered to be to attach basal keratinocytes to the basement membrane in vivo (48). Complete loss of the α6β4-integrin by targeted deletion in mice (10, 14, 46) or due to mutations in genes encoding either the α6 or β4 subunit in patients (30, 47) results in rudimentary hemidesmosomes and massive blistering upon physical stress. Decreased but not completely abolished α6(β4)-integrin expression was recently demonstrated in mice overexpressing c-Myc in the basal layer of the epidermis (12) resulting in decreased formation of hemidesmosomes and decreased assembly of the actomyosin cytoskeleton. c-Myc overexpression in mice and also in human keratinocytes promoted differentiation of epidermal stem cells rather than the induction of blisters (13). Thus, in vivo, decreased α6β4-integrin expression appears to be a prerequisite for keratinocytes to detach from the underlying basement membrane, allowing their movement to the suprabasal layers and commitment for terminal differentiation. This assumption is consistent with the fact that many HPV8 E2-expressing cells were found on top of nontransfected cells also in tissue culture.

In papillomavirus disease, β4-integrin down-regulation may ensure that virus-infected cells with higher E2 expression populate the transit-amplifying compartment within the epithelium. These cells not only support viral replication but also are committed to the differentiation process required for papillomavirus maturation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through the Heisenberg program and the SFB 589 to S. Smola-Hess. M. Oldak is a member of the Postgraduate School of Molecular Medicine affiliated with the Medical University of Warsaw. M. Aumailley is a researcher from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique.

We are grateful to U. Sandaradura de Silva for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, J. C., and F. M. Watt. 1989. Fibronectin inhibits the terminal differentiation of human keratinocytes. Nature 340:307-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aumailley, M., A. El Khal, N. Knoss, and L. Tunggal. 2003. Laminin 5 processing and its integration into the ECM. Matrix Biol. 22:49-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeckle, S., H. Pfister, and G. Steger. 2002. A new cellular factor recognizes E2 binding sites of papillomaviruses which mediate transcriptional repression by E2. Virology 293:103-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter, W. G., P. Kaur, S. G. Gil, P. J. Gahr, and E. A. Wayner. 1990. Distinct functions for integrins alpha 3 beta 1 in focal adhesions and alpha 6 beta 4/bullous pemphigoid antigen in a new stable anchoring contact (SAC) of keratinocytes: relation to hemidesmosomes. J. Cell Biol. 111:3141-3154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danen, E. H., and A. Sonnenberg. 2003. Integrins in regulation of tissue development and function. J. Pathol. 200:471-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demeret, C., A. Garcia-Carranca, and F. Thierry. 2003. Transcription-independent triggering of the extrinsic pathway of apoptosis by human papillomavirus 18 E2 protein. Oncogene 22:168-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desaintes, C., C. Demeret, S. Goyat, M. Yaniv, and F. Thierry. 1997. Expression of the papillomavirus E2 protein in HeLa cells leads to apoptosis. EMBO J. 16:504-514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desaintes, C., S. Goyat, S. Garbay, M. Yaniv, and F. Thierry. 1999. Papillomavirus E2 induces p53-independent apoptosis in HeLa cells. Oncogene 18:4538-4545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong, G., T. R. Broker, and L. T. Chow. 1994. Human papillomavirus type 11 E2 proteins repress the homologous E6 promoter by interfering with the binding of host transcription factors to adjacent elements. J. Virol. 68:1115-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowling, J., Q. C. Yu, and E. Fuchs. 1996. Beta4 integrin is required for hemidesmosome formation, cell adhesion and cell survival. J. Cell Biol. 134:559-572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feltkamp, M. C., R. Broer, F. M. di Summa, L. Struijk, E. van der Meijden, B. P. Verlaan, R. G. Westendorp, J. ter Schegget, W. J. Spaan, and J. N. Bouwes Bavinck. 2003. Seroreactivity to epidermodysplasia verruciformis-related human papillomavirus types is associated with nonmelanoma skin cancer. Cancer Res. 63:2695-2700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frye, M., C. Gardner, E. R. Li, I. Arnold, and F. M. Watt. 2003. Evidence that Myc activation depletes the epidermal stem cell compartment by modulating adhesive interactions with the local microenvironment. Development 130:2793-2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandarillas, A., and F. M. Watt. 1997. c-Myc promotes differentiation of human epidermal stem cells. Genes Dev. 11:2869-2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Georges-Labouesse, E., N. Messaddeq, G. Yehia, L. Cadalbert, A. Dierich, and M. Le Meur. 1996. Absence of integrin alpha 6 leads to epidermolysis bullosa and neonatal death in mice. Nat. Genet. 13:370-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geuijen, C. A., and A. Sonnenberg. 2002. Dynamics of the alpha6beta4 integrin in keratinocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:3845-3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green, H. 1977. Terminal differentiation of cultured human epidermal cells. Cell 11:405-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hadaschik, D., K. Hinterkeuser, M. Oldak, H. J. Pfister, and S. Smola-Hess. 2003. The papillomavirus E2 protein binds to and synergizes with C/EBP factors involved in keratinocyte differentiation. J. Virol. 77:5253-5265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall, P. A., and F. M. Watt. 1989. Stem cells: the generation and maintenance of cellular diversity. Development 106:619-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haller, K., F. Stubenrauch, and H. Pfister. 1995. Differentiation-dependent transcription of the epidermodysplasia verruciformis-associated human papillomavirus type 5 in benign lesions. Virology 214:245-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang, E. S., D. J. Riese II, J. Settleman, L. A. Nilson, J. Honig, S. Flynn, and D. DiMaio. 1993. Inhibition of cervical carcinoma cell line proliferation by the introduction of a bovine papillomavirus regulatory gene. J. Virol. 67:3720-3729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones, P. H., S. Harper, and F. M. Watt. 1995. Stem cell patterning and fate in human epidermis. Cell 80:83-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones, P. H., and F. M. Watt. 1993. Separation of human epidermal stem cells from transit amplifying cells on the basis of differences in integrin function and expression. Cell 73:713-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee, D., B. Lee, J. Kim, D. W. Kim, and J. Choe. 2000. cAMP response element-binding protein-binding protein binds to human papillomavirus E2 protein and activates E2-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 275:7045-7051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levy, L., S. Broad, D. Diekmann, R. D. Evans, and F. M. Watt. 2000. beta1 integrins regulate keratinocyte adhesion and differentiation by distinct mechanisms. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:453-466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchisio, P. C., S. Bondanza, O. Cremona, R. Cancedda, and M. De Luca. 1991. Polarized expression of integrin receptors (alpha 6 beta 4, alpha 2 beta 1, alpha 3 beta 1, and alpha v beta 5) and their relationship with the cytoskeleton and basement membrane matrix in cultured human keratinocytes. J. Cell Biol. 112:761-773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masini, C., P. G. Fuchs, F. Gabrielli, S. Stark, F. Sera, M. Ploner, C. F. Melchi, G. Primavera, G. Pirchio, O. Picconi, P. Petasecca, M. S. Cattaruzza, H. J. Pfister, and D. Abeni. 2003. Evidence for the association of human papillomavirus infection and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in immunocompetent individuals. Arch. Dermatol. 139:890-894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massimi, P., D. Pim, C. Bertoli, V. Bouvard, and L. Banks. 1999. Interaction between the HPV-16 E2 transcriptional activator and p53. Oncogene 18:7748-7754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller, A., A. Ritzkowsky, and G. Steger. 2002. Cooperative activation of human papillomavirus type 8 gene expression by the E2 protein and the cellular coactivator p300. J. Virol. 76:11042-11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Münger, K., B. A. Werness, N. Dyson, W. C. Phelps, E. Harlow, and P. M. Howley. 1989. Complex formation of human papillomavirus E7 proteins with the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product. EMBO J. 8:4099-4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niessen, C. M., M. H. van der Raaij-Helmer, E. H. Hulsman, R. van der Neut, M. F. Jonkman, and A. Sonnenberg. 1996. Deficiency of the integrin beta 4 subunit in junctional epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia: consequences for hemidesmosome formation and adhesion properties. J. Cell Sci. 109:1695-1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pear, W. S., G. P. Nolan, M. L. Scott, and D. Baltimore. 1993. Production of high-titer helper-free retroviruses by transient transfection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:8392-8396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng, Y. C., D. E. Breiding, F. Sverdrup, J. Richard, and E. J. Androphy. 2000. AMF-1/Gps2 binds p300 and enhances its interaction with papillomavirus E2 proteins. J. Virol. 74:5872-5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quandt, K., K. Frech, H. Karas, E. Wingender, and T. Werner. 1995. MatInd and MatInspector: new fast and versatile tools for detection of consensus matches in nucleotide sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:4878-4884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scheffner, M., B. A. Werness, J. M. Huibregtse, A. J. Levine, and P. M. Howley. 1990. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell 63:1129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlegel, R., W. C. Phelps, Y. L. Zhang, and M. Barbosa. 1988. Quantitative keratinocyte assay detects two biological activities of human papillomavirus DNA and identifies viral types associated with cervical carcinoma. EMBO J. 7:3181-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schmidt, H. M., G. Steger, and H. Pfister. 1997. Competitive binding of viral E2 protein and mammalian core-binding factor to transcriptional control sequences of human papillomavirus type 8 and bovine papillomavirus type 1. J. Virol. 71:8029-8034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schreiber, E., P. Matthias, M. M. Muller, and W. Schaffner. 1989. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ′mini-extracts', prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sonnenberg, A., J. Calafat, H. Janssen, H. Daams, L. M. van der Raaij-Helmer, R. Falcioni, S. J. Kennel, J. D. Aplin, J. Baker, M. Loizidou, et al. 1991. Integrin alpha 6/beta 4 complex is located in hemidesmosomes, suggesting a major role in epidermal cell-basement membrane adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 113:907-917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stepp, M. A., S. Spurr-Michaud, A. Tisdale, J. Elwell, and I. K. Gipson. 1990. Alpha 6 beta 4 integrin heterodimer is a component of hemidesmosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:8970-8974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevenson, M., L. C. Hudson, J. E. Burns, R. L. Stewart, M. Wells, and N. J. Maitland. 2000. Inverse relationship between the expression of the human papillomavirus type 16 transcription factor E2 and virus DNA copy number during the progression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J. Gen. Virol. 81:1825-1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stubenrauch, F., and H. Pfister. 1994. Low-affinity E2-binding site mediates downmodulation of E2 transactivation of the human papillomavirus type 8 late promoter. J. Virol. 68:6959-6966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takaoka, A. S., T. Yamada, M. Gotoh, Y. Kanai, K. Imai, and S. Hirohashi. 1998. Cloning and characterization of the human beta4-integrin gene promoter and enhancers. J. Biol. Chem. 273:33848-33855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan, S. H., L. E. Leong, P. A. Walker, and H. U. Bernard. 1994. The human papillomavirus type 16 E2 transcription factor binds with low cooperativity to two flanking sites and represses the E6 promoter through displacement of Sp1 and TFIID. J. Virol. 68:6411-6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tasanen, K., L. Tunggal, G. Chometon, L. Bruckner-Tuderman, and M. Aumailley. 2004. Keratinocytes from patients lacking collagen XVII display a migratory phenotype. Am. J. Pathol. 164:2027-2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van der Flier, A., and A. Sonnenberg. 2001. Function and interactions of integrins. Cell Tissue Res. 305:285-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Neut, R., P. Krimpenfort, J. Calafat, C. M. Niessen, and A. Sonnenberg. 1996. Epithelial detachment due to absence of hemidesmosomes in integrin beta 4 null mice. Nat. Genet. 13:366-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vidal, F., D. Aberdam, C. Miquel, A. M. Christiano, L. Pulkkinen, J. Uitto, J. P. Ortonne, and G. Meneguzzi. 1995. Integrin beta 4 mutations associated with junctional epidermolysis bullosa with pyloric atresia. Nat. Genet. 10:229-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watt, F. M. 2002. Role of integrins in regulating epidermal adhesion, growth and differentiation. EMBO J. 21:3919-3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watt, F. M., M. D. Kubler, N. A. Hotchin, L. J. Nicholson, and J. C. Adams. 1993. Regulation of keratinocyte terminal differentiation by integrin-extracellular matrix interactions. J. Cell Sci. 106:175-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wells, S. I., D. A. Francis, A. Y. Karpova, J. J. Dowhanick, J. D. Benson, and P. M. Howley. 2000. Papillomavirus E2 induces senescence in HPV-positive cells via pRB- and p21(CIP)-dependent pathways. EMBO J. 19:5762-5771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woodworth, C. D., S. Cheng, S. Simpson, L. Hamacher, L. T. Chow, T. R. Broker, and J. A. DiPaolo. 1992. Recombinant retroviruses encoding human papillomavirus type 18 E6 and E7 genes stimulate proliferation and delay differentiation of human keratinocytes early after infection. Oncogene 7:619-626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]