Abstract

The pathway of West Nile flavivirus early internalization events was mapped in detail in this study. Overexpression of dominant-negative mutants of Eps15 strongly inhibits West Nile virus (WNV) internalization, and pharmacological drugs that blocks clathrin also caused a marked reduction in virus entry but not caveola-dependent endocytosis inhibitory agent, filipin. Using immunocryoelectron microscopy, WNV particles were seen within clathrin-coated pits after 2 min postinfection. Double-labeling immunofluorescence assays and immunoelectron microscopy performed with anti-WNV envelope or capsid proteins and cellular markers (EEA1 and LAMP1) revealed the trafficking pathway of internalized virus particles from early endosomes to lysosomes and finally the uncoating of the virus particles. Disruption of host cell cytoskeleton (actin filaments and microtubules) with cytochalasin D and nocodazole showed significant reduction in virus infectivity. Actin filaments are shown to be essential during the initial penetration of the virus across the plasma membrane, whereas microtubules are involved in the trafficking of internalized virus from early endosomes to lysosomes for uncoating. Cells treated with lysosomotropic agents were largely resistant to infection, indicating that a low-pH-dependent step is required for WNV infection. In situ hybridization of DNA probes specific for viral RNA demonstrated the trafficking of uncoated viral RNA genomes to the endoplasmic reticulum.

The first step in the initiation of a successful virus infection cycle requires animal viruses binding to specific molecules on the cellular surface and followed by penetration into the host cells for the release of viral genome for replication. A number of different internalization and trafficking pathways are utilized by animal viruses to gain entry into host cells. These pathways include clathrin-mediated endocytosis, uptake via caveolae, macropinocytosis, phagocytosis, and other pathways that presently are poorly characterized (51). Semliki Forest virus (27), vesicular stomatitis virus (18), influenza virus (30), ecotropic murine leukemia virus (2, 34, 44), and Hantaan virus (28) gain entry into cells through a pH-dependent endocytic pathway. The acidification of endocytic vesicles trigger a conformational change in the viral envelope protein and subsequent release of viral genome at appropriate location of the cells for replication. In contrast, human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (33, 34), severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (43), and amphotrophic murine leukemia virus (34) are observed to fuse at the plasma membrane and the nucleocapsids are released into the cytoplasm. This process is a pH-independent process. The entry event is often a major determinant of virus tropism and pathogenesis (50). Understanding the early event of virus replication cycle will provide opportunities to develop strategies to block this initial but crucial interaction.

The family Flaviviridae are positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses that replicate in the cytoplasm of infected cells. Many members of the three genera (Flavivirus, Pestivirus, and Hepacivirus) belonging to this family are medically important human pathogens. The members of the genus Flavivirus are small (∼50 nm), spherical enveloped particles and include many arthropod-transmitted human pathogens: West Nile virus (WNV), yellow fever virus, dengue virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and tick-borne encephalitis virus (49). Flavivirus RNA genome encodes for three structural proteins (capsid [C], precursor of membrane [prM], and envelope [E]), and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5) that are essential for intracellular replication of the virus (12, 13, 49, 58). The RNA genome is packaged within a spherical nucleocapsid that composed of multiple copies of the capsid proteins (11, 59). The nucleocapsid is further enwrapped by a modified lipid bilayer derived from host cellular membranes through the insertion of virus structural proteins, envelope, and precursor membrane. Cleavage of prM by cellular furin or related proteases during virus maturation pathway would then release matured virus particles containing M proteins (37).

The E protein of flaviviruses has been demonstrated to play crucial role in mediating virus-host cellular receptors interaction (17, 25, 26, 48, 53). Based on the crystallography data of the tick-borne encephalitis flavivirus E protein, Rey et al. (48) noted that each E-protein monomer is folded into three distinct structural domains. The central structural domain I is the antigenic domain that carries the N glycosylation site. Structural domain II of the E protein is believed to be responsible for pH-dependent fusion of the virus E protein to the endocytic vesicles membrane during uncoating and structural domain III is important for flavivirus binding to host cells. The structural domain III of E protein contains a fold typical of an immunoglobulin constant domain and postulated to form the receptor-binding site for the virus particles. A 105-kDa protease-sensitive, N-linked glycoprotein was recently determined to be the putative receptor for WNV infection in Vero and murine neuroblastoma 2A cells (16).

A previous study by Gollins and Porterfield (21) has briefly reported that WNV is internalized into macrophage-like cell line, P388D1 cells by using endocytosis. However, the exact internalization and trafficking pathways taken by flavivirus to gain access into host cells still remains unclear. The present study documents the entry of WNV from the point of attachment to internalization, the uncoating process and, finally, the release of the virus genome.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures and virus preparation.

Vero cells (America Type Culture Collection) were maintained in Medium 199 (M199; Gibco) containing 10% inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS). Flavivirus, West Nile (Sarafend), was kindly provided by Edwin G. Westaway, Sir Albert Sakzewski Virus Research Laboratory (Queensland, Australia). Vero cells were used to propagate this virus throughout this study. Confluent monolayers of Vero cells were infected with WNV at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10. At 24 h postinfection (p.i.), the supernatant was harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 rpm for 10 min. WNV was then concentrated and partially purified by using a centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) at 2,000 rpm for 2 h. The partially purified viruses were then applied on to a 5 ml of 25% sucrose cushion for further purification. Sucrose gradient was centrifuged at 25,000 rpm for 2.5 h at 4°C in an SW55 rotor. Finally, the purified virus pellet was resuspended in Tris buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4]). The resuspended virus was divided into aliquots, snap-frozen, and stored at −80°C. The titer of the purified virus preparation was determined by plaque assay on Vero cells and was found to be 9 × 108 to 5 × 109 PFU/ml. For preparation of radiolabeled-WNV, Vero cells were inoculated with WNV at an MOI of 10 and incubated at 37°C in maintenance medium (2% FCS-M199). At 4 h p.i., cells were starved in methionine-free medium for 1 h, and the medium was then replaced by 0.5% FCS-M199 containing 5 μCi of l-[35S]methionine and 2 μg of actinomycin D (Sigma)/ml. At 24 h p.i., infected cell culture supernatant was harvested, and extracellular virus was purified as described above in a sucrose gradient. The specific infectivity and radioactivity of the radiolabeled virus preparation were 9 × 108 PFU/ml and 4 × 104 cpm/ml, respectively.

Antibodies and reagents.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies against WNV (H546) were purchased from Microbix Biosystems, Inc. The antibody for WNV E protein was a monospecific polyclonal antibody, kindly provided by Vincent Deubel, Pasteur Institute, Paris, France. The anti-C protein antisera were a generous gift from Edwin G. Westaway, Sir Albert Sakzewski Virus Research Laboratory (Queensland, Australia). Mouse monoclonal antibodies to cellular proteins, clathrin, caveolin, early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1), lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), and Bip (endoplasmic reticulum [ER] marker) were purchased from BD Pharmingen and anti-Golgi zone was purchased from Chemicon. The secondary antibodies conjugated to Texas red (TR) or fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech. Lysotracker (a stain for late endosomes and lysosomes) was purchased from Molecular Probes. Fifteen- and ten-nanometer protein A-colloidal gold was purchased from Agar Aids. Monodanslycadervine, chlorpromazine, filipin, nocodazole, cytochalasin B, bafilomycin A, amantidine, chloroquine, and acridine orange were purchased from Sigma.

Transfections.

Plasmid constructs of dominant-negative Eps15 (GFP-EΔ95/295) was kindly provided by A. Benmerah, Pasteur Institute, and plasmid constructs backbone EGFP-C2 was purchased from Clontech. Unless stated otherwise, transfections were performed by using Lipofectamine Plus reagents from Invitrogen as specified by the manufacturer. In brief, Vero cells were grown on coverslips in 24-well tissue culture plate until 75% confluency. Then, 2.5-μg portions of the respective constructs was complexed with 4 μl of Plus reagent in 25 μl of OPTI-MEM medium (Gibco) for 15 min at room temperature. The mixture was then added to 25 μl of OPTI-MEM containing 2 μl of Lipofectamine. After incubation for another 15 min, the DNA-liposome complexes were added to the cells. After incubation for 3 h at 37°C, 1 ml of complete growth medium was added and incubated for another 24 h before virus entry assay was carried out.

Indirect immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy.

For immunofluorescence microscopy, cell monolayers were first grown on coverslips till 75% confluency. The subsequent procedure is similar to that described in reference 15. The primary antibodies to clathrin, caveolin, EEA1, LAMP1, and Bip were used at concentrations of 0.25 and 0.2 μg/ml for anti-WNV antibodies. TR- or FITC-conjugated secondary antibodies were used at a concentration of 0.1 μg/ml. The specimens were then viewed with a laser scanning confocal inverted microscope (Leica TCS SP2) with an excitation wavelength of 543 nm for TR and 480 nm for FITC by using a ×63 objective lens.

Negative staining of WNV preparation.

For negative staining of WNV preparation, 10 μl of WNV was added to freshly glow discharged, carbon-coated grids, and stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 1 min. The grids were then air dried before viewing under the CM120 Biotwin transmission electron microscope (Philips).

Cryoimmunolabeling electron microscopy.

Vero cells were incubated with WNV (MOI = 25) at 4°C for 30 min to allow synchronous virus attachment to the plasma membrane. Cells were then incubated for 1, 3, 5, 15, and 30 min at 37°C and processed for cryoelectron microscopy by the Tokuyasu method (54) with some modifications as described in Ng et al. (42). Briefly, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.2% glutaraldehyde, followed by embedding in gelatin. The gelatin block with the cells was immersed in cryoprotectant, rapidly frozen before cryoultramicrotomy (UCT with the EM FCS Cryo-Attachment; Leica).

For immunolabeling (42), the primary antibodies, anti-EEA1, LAMP1, WNV C protein, and WNV E protein were used, followed by conjugation with protein A-colloidal gold (Agar Aids) at a dilution of 1:20. The sections were viewed under a CM120 Biotwin transmission electron microscope (Philips).

Preparation of digoxigenin-11-dUTP incorporated DNA probes.

The DNA probes used for in situ hybridization were prepared as previously described by Grief et al. (22) and An et al. (1). The first-round PCR was performed with the oligonucleotide primers PE1 (5′-AGCTTCAACTGTTTAGGAATGA) and PE2 (5′ CACCTTCCTGCGACCCTAGAG), which amplified a region of the viral E protein gene (784 bp) from plasmid pWNVE. Plasmid pWNVE was constructed by ligating the full-length E protein gene of WNV (Sarafend) into plasmid pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). The resulting amplified products were used for a second round and asymmetric PCR with primer PE3 (5′-GGAGTTATGCTGAACCTTCC) to generate the complementary (negative) single-stranded probes with the incorporation of digoxigenin-11-dUTP (Roche) (1). The incorporation of digoxigenin-11-dUTP was checked by immunospotting the probes onto nylon membrane as described in reference 1. To perform in situ hybridization on cryosections of cells, the DNA probes were first diluted in hybridization buffer, and hybridization was carried out as described in reference 22. After hybridization, the sections were viewed by using a CM120 Biotwin transmission electron microscope.

Percoll fractionation of cell homogenates.

Vero cells were infected with 35S-labeled WNV at an MOI of 10 for 1 h at 4°C. Unbound virus was removed by two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were then allowed to internalize WNV for 5, 15, and 30 min at 37°C. At appropriate times after internalization of virus particles, the cells were washed twice with cold PBS before being detached by gentle scraping. After centrifugation for 10 min at 1,500 rpm, the cell pellet was resuspended in homogenization buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, protease cocktail inhibitor [pH 7.4]). The suspension was subjected to 20 strokes in a tight-fitting homogenizer (Jensons). The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000 rpm (to remove the nuclei), and the postnuclear supernatant was collected. For the separation of subcellular particles in the postnuclear supernatant, an isosmotic solution of 20% Percoll was prepared as previously described (46). The postnuclear supernatant samples were centrifuged at 32,000 × g for 30 min in a Beckman 70.1 Ti rotor. Density marker beads (Pharmacia Biotech) were used as external standards for the density gradients in the Percoll solution. Fractions of 250 μl were collected and processed for liquid scintillation counting of 35S-labeled WNV radioactivity in a Beckman LS6500 liquid scintillation counter.

Virus entry assay and drug treatments.

Vero cells growing on coverslips were incubated with WNV at an MOI of 10 for 1 h at 4°C with gentle rocking. Unbound virus was washed three times in ice-cold PBS and shifted to 37°C for 1 h in growth medium to allow virus penetration. Extracellular virus that failed to enter into cells was inactivated with sodium citrate buffer (pH 2.8) as described by Chu and Ng (16). Infected monolayers were washed twice with PBS and further incubated at 37°C for 24 h. At 1 day p.i., cells were fixed in methanol and processed for immunofluorescence assay as described above. The number of infected cells is scored in comparison to mock-infected cells.

To determine the effects of the drugs used to inhibit the entry of WNV, Vero cells were either pretreated with drugs (as listed below) for 1 h at 37°C, followed by virus infection, or the drugs were added at 10 min, 30 min, 1 h, or 2 h p.i. Cells were infected as described above and processed for immunofluorescence assay. Three independent experiments were carried out for each set of drugs used. The inhibition of virus entry was determined by determining the number of virus antigen-positive cells in relation to the total number of cells (virus antigen positive and negative) and is expressed as the percentage virus antigen-positive cells.

The drugs used in the present study were as follows: inhibitor of receptor-mediated endocytosis, monodanslycadervine (0.5 mM); inhibitors of clathrin function, chlorpromazine (5 μg/ml) and sucrose (0.3 M); inhibitor of caveola-dependent endocytosis, filipin (1 μg/ml); lysosomotropic drug, chloroquine (15 μM) and amantidine (0.5 μM); vacuolar-ATPase inhibitor, bafilomycin A1 (0.1 μM); and inhibitor of the endocytotic trafficking pathway, cytochalasin B (1 μg/ml) and nocodazole (5 μM).

RESULTS

Localization of viral envelope protein in WNV replication cycle.

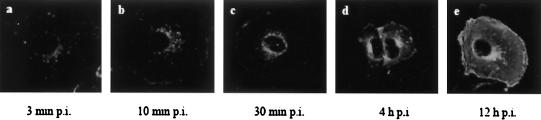

Unlike many of the flaviviruses, WNV has a relatively short latent period of 4 to 6 h p.i (42) compared to those of other flaviviruses (16 to 24 h p.i.). By 12 h p.i., progeny virions are extensively released by budding at the plasma membrane of infected cells. Maximum extracellular virus titers were obtained by 18 h p.i (15). By using immunofluorescence microscopy, the general course of WNV replication was traced. WNV envelope protein antibody was used as a marker to follow the movement of the virus from entry to egression. At 3 min p.i., WNV was observed at the plasma membrane, as well as vesicle-like distribution in the cytosol, close to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1a). The vesicle-like distribution of the virus particles was seen moving toward the perinuclear region by 10 min p.i., and a small amount of virus was still found at the cell surface (Fig. 1b). At 30 min p.i., virus particles were localized to the perinuclear region in the majority of the WNV-infected cells (Fig. 1c). No viral E protein was observed in the nucleus of the cell. Newly synthesized viral E proteins were detected by 4 h p.i. at the perinuclear region in close association with the endoplasmic recticula and radiating out into the cytoplasm (Fig. 1d). As infection progressed to 12 h p.i., a large amount of viral E protein was detected throughout the infected cell, with predominant distribution at the perinuclear region and the plasma membrane (Fig. 1e).

FIG. 1.

Localization study of WNV envelope protein in Vero cells during the infection cycle. At different times p.i. (a, 3 min; b, 10 min; c, 30 min; d, 4 h; e, 12 h), Vero cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence assay. WNV E protein was detected with polyclonal anti-WNV E protein and with anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated with FITC as the secondary antibody.

Cryo-immunoelectron microscopy analysis of WNV entry route.

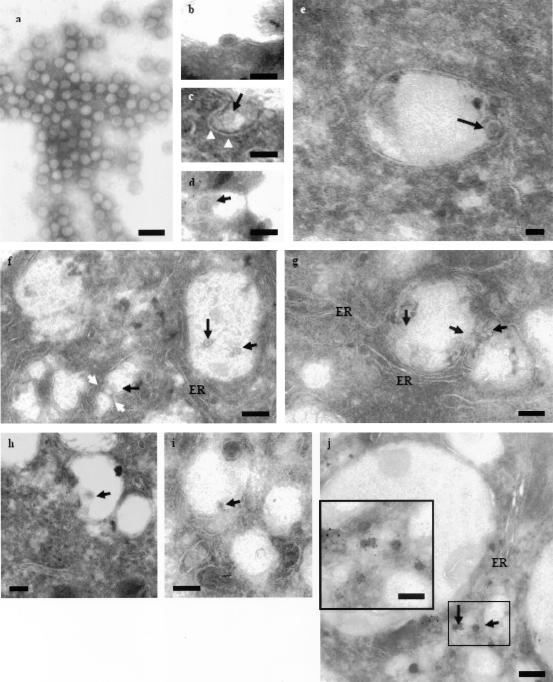

In the present study, WNV were first prepared by a series of concentration and purification procedures. As revealed by negative staining of the virus preparation, a homogeneous population of WNV particles with a uniform size of 50 nm in diameter (Fig. 2a) was obtained. The purified virus was subsequently used in the ultrastructural study in virus entry process. To better define the entry route of WNV into cells, cryofixation coupled with immunoelectron microscopy was used to visualize the entry process at the ultrastructural level. A previous study by Ng et al. (42) have clearly illustrated that cryofixation can preserve virus and cellular structure much better than conventional chemical fixation. Immunolabeling can also be performed without compromising the antigenicity.

FIG. 2.

Ultrastructural analysis of WNV entry process by using immunocryoelectron microscopy. (a) Homogeneous population of negatively stained WNV particles. (b) Binding of WNV particle at the plasma membrane of Vero cells. (c) Uptake of WNV particle (arrow) by coated pit (arrowheads). (d) WNV particle (arrow) is internalized within a clathrin-coated pit as indicated by the 10-nm gold particles. (e) Localization of single WNV particle in endocytic vesicles. (f) Fusion of WNV (black arrows) containing endocytotic vesicles (white arrows) that formed multivirus-containing compartments. (g) Multivirus-containing endocytotic vesicles are found in close proximity to the ER compartments. Virus particles are indicated by arrows. (h) Fusion of the WNV particle (arrows) with the endocytotic vesicle membrane. (i) Expulsion of the nucleocapsid of WNV (arrows) after fusion of the viral envelope with the endocytotic membrane. (j) Immunodetection of WNV nucleocapsid particles in the cytoplasm with gold particles conjugated to anti-capsid serum. Bars represent 100 nm (a to d) 200 nm (f, g, and j), 50 nm (e and j, inset), or 100 nm (h).

In order to visualize synchronized entry of WNV, Vero cells were first incubated with WNV (MOI = 25) at 4°C for 1 h. Low-temperature treatment allows binding of WNV to the cell surface receptors but prevents the internalization of virus particles into the cells. Subsequently, the cells were warmed to 37°C, and the virus-infected cells were processed for cryosectioning at appropriate times after warming. At 0 min upon warming to 37°C, attachment of WNV particles along the cell surface of Vero cells was observed (Fig. 2b). At 3 min after warm-up, WNV particle (arrow) was found within invaginations of the plasma membrane. These invaginations resembled those of clathrin-coated pits (Fig. 2c, arrowheads). To determine whether clathrin is involved in the initial internalization of WNV, cryosections were immunolabeled with anti-clathrin and conjugated to gold particles. Figure 2d shows the uptake of WNV (arrow) via a clathrin-coated pit, as indicated by the 10-nm gold particles binding to anti-clathrin antibodies.

After 5 min at 37°C, most of the virus particles are observed within endocytic vesicles. Single virus particle was contained within each of these vesicles (Fig. 2e). By 10 min, vesicles containing single virus particle (Fig. 2f, black arrows) are seen fusing with one another (Fig. 2f, white arrows) resulting in the formation of large electron-lucent vesicles (∼500 nm in diameter) containing several virus particles. These virus-containing vesicles are predominantly localized to the perinuclear region in close association with the ER. WNV particles are indicated by the arrows (Fig. 2g). Thus far, it has been a challenge to visualize the uncoating process of flaviviruses in endocytic vesicles. It is believed that the acidification of the endocytic vesicles would cause the fusion of the viral envelope protein with the endocytic vesicle membrane and triggered the release of the flavivirus nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm. Figure 2h and i show the fusion process of WNV particles with the endocytic vesicle membrane (by 15 min) to expel the viral RNA-containing nucleocapsids into the cytosol. In Fig. 2 h, the viral envelope has loosened and fused with the endocytic vesicles membrane (arrow). Figure 2i shows the release of the viral nucleocapsid (arrow) after fusion with the membrane of the endocytic vesicle. With the superiority of cryofixation procedure, released viral nucleocapsid particles in the cytoplasm was visualized in the present study. Nucleocapsid particles (arrows [labeled by anti-WNV capsid antibodies conjugated to 10-nm gold particles]) were observed in proximity with the endocytic vesicles and the ER region (Fig. 2j). The inset shows a higher magnification of the boxed area.

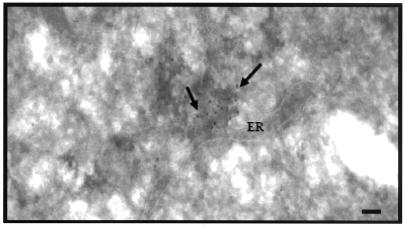

To investigate the location of the viral RNA genome upon release from the nucleocapsid, in situ hybridization with digoxigenin-11-dUTP (DGdUTP)-incorporated DNA probes coupled with cryoimmunoelectron microscopy were used. Hybridization of the synthesized cDNA probe to the viral RNA was detected by using anti-digoxigenin, which was further conjugated with 10-nm gold particles. The specificity of the synthesized DNA probes binding to the viral RNA was assessed. No hybridization signal (absence of gold particle decoration) was detected when cryosections of uninfected Vero cells were incubated with the synthesized DNA probes (results not shown). In addition, hybridization signals were not detected for RNase-treated cryosections of WNV-infected cells (data not shown). For WNV-infected cells, viral RNA (as indicated by the 10-nm gold particles) was found in close proximity with the ER after 20 min at 37°C (Fig. 3). Virus particles were no longer detectable within the endocytic vesicles that were located near the ER, as previously observed in Fig. 2g and h. This observation is consistent with previous studies that have documented that the ER is the site of flavivirus replication (40, 41, 60).

FIG. 3.

The uncoated WNV RNA genome is associated with the ER. WNV RNA genome was detected by using immunogold labeling against DGdUTP (black arrows) that are incorporated into the DNA probes. Bar, 50 nm.

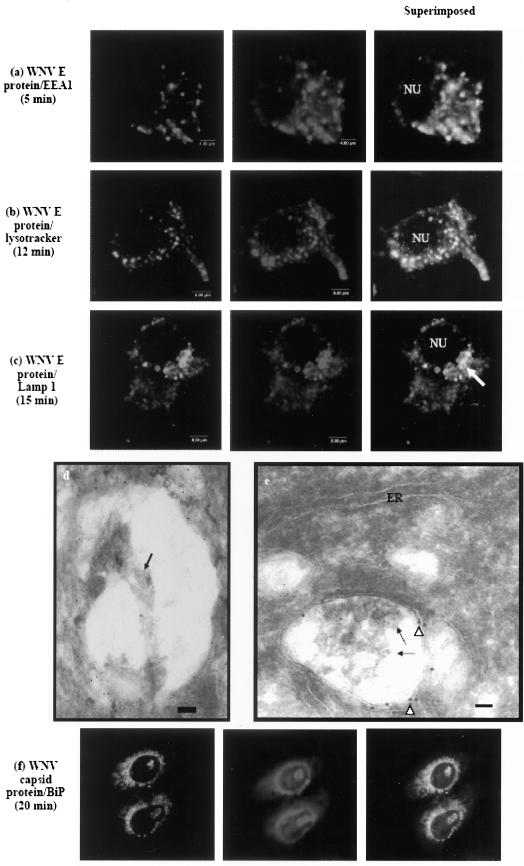

To further characterize the origin of the cellular components that were involved in the entry process of WNV, double-labeled immunofluorescence, confocal laser scanning microscopy, and immunogold labeling electron microscopy were performed at the same appropriate times. Antibodies specific for endosomes (EEA1), lysosome (LAMP1), RER (Bip), and Lysotracker (specific staining of late endosomes and lysosomes; Molecular Probes) were used in part of the study.

At 3 to 5 min after cells were warmed to 37°C, a double-labeled immunofluorescence assay with anti-WNV envelope protein and anti-EEA1 antibodies showed colocalization, suggesting that the virus particles were translocated to the endosomes after endocytosis. At these times, most of the virus-containing endosomes were distributed closer to the cell periphery (Fig. 4a). Similarly, WNV particles were seen within early endosomes, as indicated by the 10-nm gold particles bound to antibodies against EEA1 by using immunogold-labeled electron microscopy (Fig. 4d). By 12 min after a shift up to 37°C, WNVs are found mainly in vesicles (Fig. 4b) that were stained with Lysotracker (Molecular Probes), suggesting that WNV were localized to the late endosomes and lysosomes by this time point. The fluorescent staining was more intense at the perinuclear region. A unique accumulation of a large number of virus-containing late endosomes and lysosomes were observed at the perinuclear region by 15 min (Fig. 4c, white arrow), and these structures remained until 30 min p.i. (data not shown). Immunogold labeling electron microscopy further confirmed the identity of these virus-containing vesicles as lysosomes. Gold particles (white arrowheads; 15 nm in diameter) binding to antibodies against LAMP1 were localized around the lysosomal membrane. The antibodies to envelope proteins of the WNV were also labeled with 10-nm gold particles (arrows). Several virus particles with loosened envelope and fusion with the lysosomal membrane can be observed (Fig. 4e). In addition, attempts were made to localize the distribution of viral nucleocapsid in the cytoplasm after uncoating. Viral capsid proteins were observed to colocalize strongly (yellow staining) with the cellular marker (BiP) for ER (Fig. 4f) but not the Golgi complex in a double-labeled immunofluorescence assay (data not shown).

FIG.4.

Colocalization of WNV with early and late endocytic vesicles markers. (a) Anti-EEA1 was used to stain the early endosomes at 5 min p.i. Lysotracker (b) and anti-LAMP1 (c) were used to stain late endosomes and lysosomes at 12 and 15 min p.i., respectively. EEA1 and LAMP1 antibodies are conjugated with Texas Red (TR), and WNV E protein antibody is conjugated with FITC. (d) A WNV particle (arrow) is localized within early endosomes, as indicated by gold particles conjugated to anti-EEA1 antibodies. (e) LAMP1-positive lysosome (gold particles [arrowheads]) containing large number of WNV particles (arrows) can be seen in close association with the ER. The virus particles are decorated with gold particles conjugated with anti-WNV E protein. (f) Colocalization of WNV nucleocapsids with ER marker. Anti-BiP and anti-capsid sera are used to stain the ER and nucleocapsid, respectively. WNV nucleocapsids were localized to the ER. BiP marker is conjugated with TR, and capsid protein antibody is conjugated with FITC. Bars (d and e), 50 nm. NU, nucleus.

The results presented above suggested the involvement of a clathrin-mediated endocytic pathway in WNV entry into Vero cells. To affirm these results, Vero cells were treated with drugs that selectively inhibit receptor-mediated endocytosis (monodanslycadervine), clathrin-dependent endocytosis (chlorpromazine and sucrose), and caveola-dependent endocytosis (filipin, which disrupts the cholesterol-rich caveola-containing membrane microdomain).

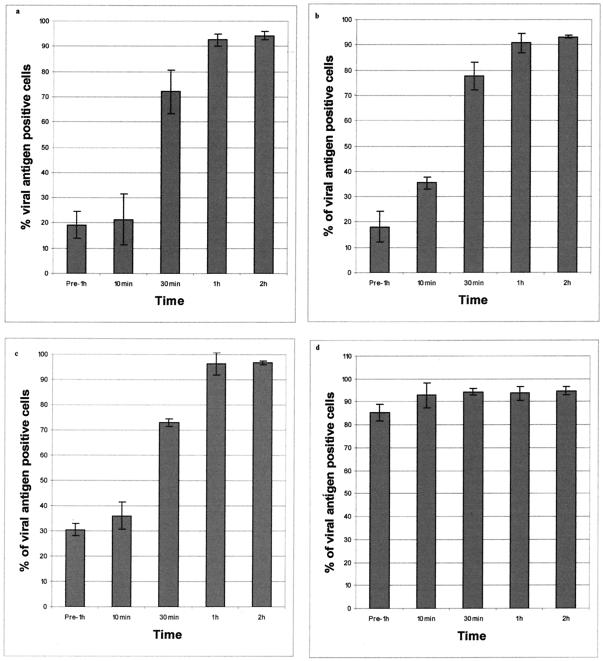

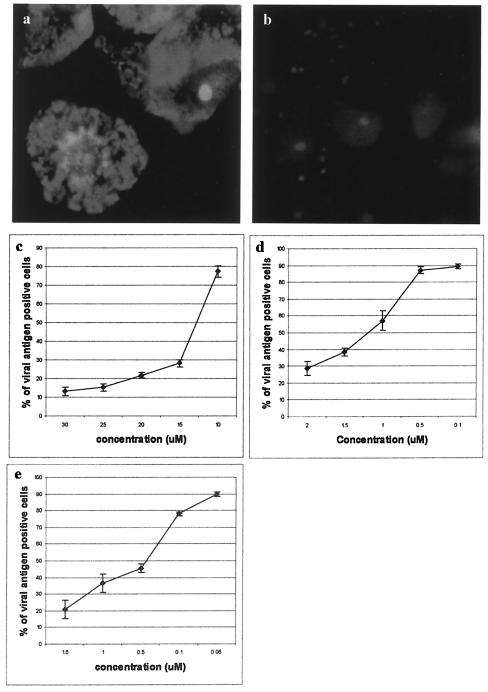

Pretreatments of Vero cells with monodanslycadervine, chlorpromazine, and sucrose for 1 h before WNV infection or administration of these drugs at 10 min p.i. significantly reduced the number of infected cells. However, monodanslycadervine, chlorpromazine, and sucrose did not seem to exert any inhibitory effect on WNV infection when these drugs were added 1 and 2 h p.i. This result suggested that these drugs selectively blocked an early step in the entry process of WNV (Fig. 5a, b, and c, respectively). In contrast, filipin had no significant effect on WNV infection regardless of the timing of the drug added to the cells (Fig. 5d).

FIG. 5.

Effects of clathrin-mediated endocytosis-disrupting drugs on WNV entry into Vero cells. The percentage of viral antigen-positive cells was plotted against time. Cells treated with monodanslycadervine (a), chlorpromazine (b), or sucrose (c) showed marked reduction in WNV entry, whereas filipin (d) does not significantly inhibit virus entry. The average of three independent experiments is shown.

Molecular inhibitors in the form of dominant-negative mutants were also used to further confirm the role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in the entry of WNV. The use of dominant-negative mutants may provide an alternative way to analyze the specific function of defined pathways within the cells. A study by Benmerah et al. (6) showed that Eps15, a protein that binds to the AP-2 adapter, is required for internalization through clathrin-coated pits. However, the deletion of the EH domain of Eps15 produced a dominant-negative mutant of the protein that arrests clathrin-coated pit formation (7) and inhibits the uptake of transferrin (a cellular marker of clathrin-mediated endocytosis).

In this part of the study, Vero cells were first transfected with either GFP-EΔ95/295 plasmid (dominant-negative mutant) or EGFP-C2 plasmid (coding for green fluorescent protein [GFP] as an internal control) as previously described by (6). Transfected cells were then assayed for their capacity to internalize TR-conjugated transferrin and WNV. The internalization of TR-transferrin was impaired in cells expressing GFP-EΔ95/295, but not in cells that express GFP, when visualized under a confocal scanning laser microscope (data not shown).

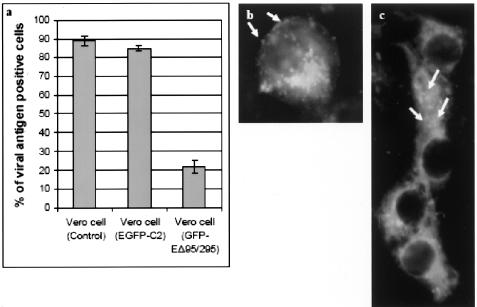

As shown in Fig. 6a, the uptake of WNV was drastically reduced in cells transfected with GFP-EΔ95/295 plasmid compared to cells that were transfected with EGFP-C2 plasmid alone or to mock-transfected Vero cells. GFP-EΔ95/295 expressing cells are also incubated with WNV at 37°C for 30 min and processed for immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy. WNV particles (stained by anti-WNV E protein antibodies conjugated to TR [arrows]) were observed to attach and accumulate exclusively on the plasma membrane but failed to enter the cells (Fig. 6b, arrows). In contrast, Fig. 6c shows the internalization of WNV (arrows, speckled staining) within the cytoplasm of GFP-expressing cells. These results together provide strong evidence that WNV entry into cells takes place through clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

FIG. 6.

Inhibition of WNV entry into Vero cells expressing Eps15 dominant-negative mutant protein. (a) The entry of WNV was significantly inhibited in Vero cells transfected with GFP-EΔ95/295. The number of viral E antigen-positive cells in relation to the total cell population is expressed as a percentage of viral antigen-positive cells. (b) Binding of WNV (stained with TR [arrows]) on the plasma membrane of the GFP-EΔ95/295-expressing cell was observed but no internalization of the virus particles occurred. (c) Internalized WNV particles (arrows) are observed within cells expressing the negative control plasmid expressing GFP.

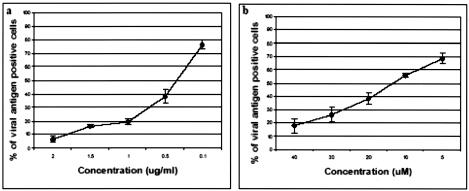

Clathrin-mediated entry pathway can be inhibited at different stages by specific drugs such as cytochalasin D and nocodazole. Cytochalasin D and nocodazole induced depolymerization of actin filaments and microtubules, respectively. Durrbach et al. (19) documented the sequential involvement of both actin filaments and the microtubule network in the trafficking pathway of ligands via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Pretreatment of Vero cells with increasing concentrations of either cytochalasin D or nocodazole revealed a dose-dependent inhibition of WNV infection. Noncytotoxic concentrations of cytochalasin D (0.1 to 2 μg/ml) and nocodazole (5 to 40 μM) prevented WNV infection significantly (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Cytochalasin D- and nocodazole-pretreated Vero cells inhibit entry of WNV. The percentage of viral antigen-positive cells is plotted against time. A dose-dependent inhibition of WNV internalization into cytochalasin D (a)- and nocodazole (b)-treated Vero cells is observed. The average of three independent experiments is shown.

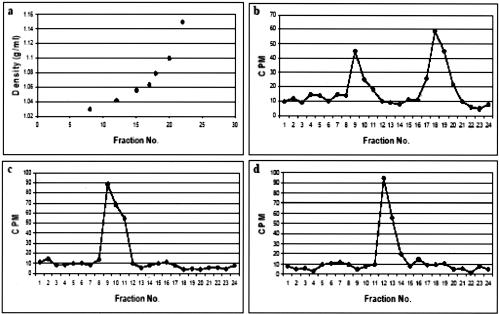

To further investigate the specific locations at which these drugs affect the entry of WNV, cellular fractionation of homogenized WNV-infected cells in 20% Percoll gradients were performed. Cellular fractionation in a 20% self-generated Percoll gradient allowed the separation of subcellular particles based on buoyant density. Density marker beads (Amersham Pharmacia) were used as external markers to facilitate the density measurement of the separated subcellular particles in the gradient. The densities of the endosomes, lysosomes, plasma membrane, and ER were predetermined and were determined to be 1.034, 1.075, 1.045, and 1.058 g/ml, respectively (data not shown).

In this experiment, Vero cells were either pretreated with cytochalasin D (2 μg/ml) or nocodazole (40 μM) for 1 h before incubation with 35S-radiolabeled WNV at an MOI of 10. At 30 min p.i., the WNV-infected cells were subjected to homogenization, followed by fractionation in a Percoll gradient. A total of 24 fractions were collected and analyzed for radioactivity counting. For the untreated Vero cells, two peaks of radioactivity were detected (Fig. 8b). The densities of the radioactive peaks were determined relative to the density bead makers based on their positions in the Percoll gradient as shown in Fig. 8a. The density of the first peak corresponded closely to the endosomal marker fraction (1.034 g/ml), whereas the second peak was in the vicinity of the lysosomal marker fraction (1.075 g/ml). For the nocodazole-treated cells, the radioactive WNV particles were observed in a single density fraction that corresponded to the early endosome marker fraction (1.034 g/ml; Fig. 8c). Hence, the intact microtubules network is indeed necessary for the trafficking of the internalized WNV from early to late endosomes. As for the cytochalasin D-treated cells, a single radioactive peak was detected, and this peak corresponded to the plasma membrane marker fraction (density of 1.045 g/ml; Fig. 8d), suggesting that the perturbation of actin filaments might have prevented internalization of the attached virus particles on the plasma membrane.

FIG. 8.

Subcellular fractionations of cellular homogenates from WNV-infected cells in 20% Percoll gradients. (a) Standard plot of density distribution determined by density marker beads in the 20% Percoll gradient. (b) Vero cells are allowed to internalized radiolabeled WNV at an MOI of 10 for 30 min and subjected to cellular fractionation. (c and d) A procedure similar to that for panel b was carried out except that the Vero cells were pretreated (1 h) with nocodazole and cytochalasin D, respectively.

Finally, assays to examine pH-dependent entry of WNV in the presence of lysosomotropic weak bases (chloroquine and amantidine) and vacuolar H+-ATPase (VATPase) inhibitor (bafilomycin A) were also carried out. Lysosomotropic weak bases act by raising the pH within acidic vesicles and thus function as a proton sink. Bafilomycin A is a potent and specific inhibitor of VATPase that inhibits endosome and lysosome acidification (61). To ensure that the concentrations of the drugs used in this experiment can inhibit the acidification of the endocytic vesicles, intracellular acidic vesicles were stained with acridine orange and observed under a fluorescence microscope.

For untreated Vero cells, granular orange fluorescence was observed (Fig. 9a), and this is consistent with the descriptions reported by Nawa (38) and Umata et al. (55). The granular orange fluorescence was totally abolished in cells that were treated with 1.5 μM chloroquine (Fig. 9b), 1 μM amantidine, and 0.5 μM bafilomycin A (data not shown). To analyze the effect of chloroquine, amantidine, and bafilomycin A on the entry mechanism of WNV, Vero cells were pretreated with increasing noncytotoxic concentrations of each drugs, followed by WNV infection.

FIG. 9.

pH-dependent entry pathway of WNV into Vero cells. (a and b) Acridine orange staining of untreated Vero cells (a) and cells after incubation with 1.5 μM chloroquine (b). Acridine orange staining of acidic vesicles in chloroquine-treated cells (a) was abolished compared to the untreated cells (b). Inhibitory effect on the entry of WNV into pretreated Vero cells with bafilomycin A (c), chloroquine (d), and amantidine (e). A dose-response inhibition of WNV entry was observed for all three of the drugs used. The average of three independent experiments is shown.

Cells were assayed for infectious entry of WNV by counting the number of viral envelope protein-expressing cells. All three drugs (Fig. 9c, bafilomycin A; Fig. 9d, chloroquine; Fig. 9e, amantidine) caused a marked reduction of WNV infection at 12 h p.i. in a dose-dependent manner. Possible cytotoxic effects of the drugs were assessed by trypan blue exclusion procedure and observation of morphological changes. Minimal cell toxicity was observed in drug-treated cells throughout the spectra of concentrations used in this experiment.

DISCUSSION

The early events of viral infection usually involve the attachment of virus to cellular receptor molecules on the plasma membrane of host cells. This is followed by internalization, uncoating, and subsequent virus gene transcription and/or translation at specific locations in cells. Studies have clearly demonstrated that animal viruses can utilize different internalization and trafficking pathways that allow specific localization within the cells upon entry for a successful infection (15). For enveloped viruses, the entry process can occur either via the fusion of virus envelope glycoproteins at the plasma membrane at neutral pH to promote the internalization of viral nucleocapsids or virus particles undergoing endocytosis prior to fusion with endocytic membrane. For the latter, conformational change of the virus fusion protein to expose the hydrophobic fusion peptide is induced by an acidic pH for the release of the viral nucleocapsids into the cytoplasm (14).

In the present study, a variety of experimental approaches was utilized to study the detail entry pathway taken by flavivirus WN during the early events of infection. The entry process of WNV into Vero cells began with the attachment of the virus particles at the cell surface (Fig. 2b), which is followed by a clathrin-mediated endocytic pathway to internalize WNV particles (Fig. 2c to e). WNVs are then trafficked along an endosomal and lysosomal endocytic pathway (Fig. 2e to h and 4b and c) with the involvement microtubules network and, subsequently, a pH-dependent fusion mechanism to expel the viral nucleocapsid into the cytoplasm in close proximity to the ER (Fig. 2i and j, 3, and 4e and f).

Beasley and Barrett (5) have recently identified neutralizing epitopes within structural domain III of the WNV E protein and concluded that the structural domain III is the likely receptor-binding domain. The cellular counterpart of domain III has also recently identified as a 105-kDa plasma membrane-associated protein by Chu and Ng (16).

Upon attachment of WNV to the cell surface, WNV particles are internalized within 2 to 3 min after the temperature shift from 0 to 37°C (Fig. 2c). As illustrated ultrastructurally with immunogold labeling against anti-clathrin antibodies on cryosections, WNVs are localized within clathrin-coated pits (Fig. 2d). To further confirm that WNVs are being internalized by clathrin-mediated endocytosis, Vero cells were treated with pharmacological agents (monodanslycadervine, chlorpromazine, and sucrose Fig. 5a to c) that inhibit receptor-mediated endocytosis and clathrin functions. Chlorpromazine has been extensively used to study virus entry. Involvement of clathrin-mediated endocytosis of influenza virus (32), polyomavirus JC virus (45), picornavirus parechovirus type I (29), and the Japanese encephalitis virus (39) was demonstrated with the actions of chlorpromazine. Chlorpromazine acts by accumulating clathrin and AP-2 in endosomal compartments, hence preventing the formation of clathrin-coated pits at the plasma membrane.

High concentrations of sucrose can also be used to inhibit clathrin-mediated endocytosis by inducing hypertonicity that deplete potassium ions, thus causing clathrin to dissociate (8). The involvement of clathrin in human rhinovirus infection and Hantaan virus infection was illustrated by potassium depletion studies (28, 4). The WNV internalization was significantly inhibited when Vero cells were pretreated with noncytotoxic concentrations of chlorpromazine and sucrose (Fig. 5b and c). In contrast, filipin (which inhibits caveola-dependent endocytosis) did not significantly affect WNV infection (Fig. 5d). These results were further supported by the finding determined by immunofluorescence assay that WNV colocalized with clathrin but not caveolin (data not shown).

The formation of clathrin-coated pits at the plasma membrane during the process of receptor-mediated endocytosis requires the interaction of clathrin, along with its accessory factors (57). These accessory factors serve important roles in the regulatory and catalytic mechanism at specific stages in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. One of the newly discovered accessory factors, Eps15 is ubiquitously and constitutively associated with AP-2 for the formation of clathrin-coated pits at the plasma membrane. Studies by Carbone et al. (10) and Benmerah et al. (6) showed that the overexpression or microinjection of dominant-negative mutants of Eps15 strongly inhibits clathrin-dependent endocytosis. Expression of dominant-negative Eps15 in Vero cells demonstrated strong inhibition of WNV uptake (Fig. 6). It was also noted that the inhibition of clathrin-coated pits formation at the plasma membrane did not affect the binding of WNV particles to the cell surface, as revealed by immunofluorescence assay (Fig. 6b). The data thus far provide strong evidence that the initial internalization of WNV after attaching to the plasma membrane proceeds by clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

After internalization by clathrin-mediated endocytosis, the virus particles are trafficked along the cellular endocytic pathway. The endocytic pathway also serve as a rapid transit system in the delivery of viral cargo to specific locations within cells for its replication. At present, two principle postinternalization endocytic trafficking routes are known: recycling or the lysosome-targeted pathway (23). For the latter, acidification within the vesicles is one characteristic of the endocytic pathway. This process has been shown to be essential for the uncoating of many enveloped viruses. Viruses such as adeno-associated viruses (3) and human rhinovirus HRV14 (4) have been shown to escape or undergo uncoating in early endosomes, whereas many other viruses (poliovirus type 1 and mouse Elberfeld virus) are trafficked from early endosomes to late endosomes and then to lysosomes for uncoating (62).

By 5 min after internalization, most WNVs are observed singly within endocytic vesicles, and these vesicles are identified as early endosomes based on morphological characteristics and immunolabeling with the cellular marker EEA1 (Fig. 2e and 4a). Colocalization of WNV- with LAMP1-positive vesicles was observed by 15 min after entry (Fig. 4c). The trafficking process of WNV along the endocytic pathway seemed to occur rapidly (within 15 min of attachment) and was consistent with the speed of typical trafficking of cellular ligands such as transferrin or epidermal growth factor that utilized clathrin-mediated endocytosis (31, 35). The trafficking-maturation model of endosomes has suggested that endosomes act as transient independent carriers that progressively change in size and shape by homologous fusion and eventually mature into late endosomes and lysosomes (23, 52). This was also observed in the trafficking of WNV; endosomes containing single WNV particles were observed to fuse with each other, resulting in the formation of large endocytic vesicles (late endosomes and lysosomes) that contained several virus particles (Fig. 2f and g and 4b and c). Therefore, the data showed that after the internalization of WNV by clathrin-mediated endocytosis, the virus particles were trafficked through the endosomes and eventually to the late endosomes and lysosomes.

Host cytoskeleton, namely, the actin filaments and microtubules, has been observed to be involved in the trafficking of endocytic compartments containing internalized ligand-receptor complexes. Actin filaments are required for the initial uptake of ligands and subsequent degradative pathway, whereas microtubules are involved in maintaining the endosomal traffic between peripheral early and late endosomes (19). Recent evidence has suggested that actin cytoskeleton is closely associated with clathrin-coated pits and that actin polymerization may be involved in moving endocytic vesicles into cytosol after they are pinched off from the plasma membrane (47). The actin-binding molecular motor, myosin VI, was also recently shown to mediate clathrin endocytosis (9). Disruption of actin filaments can have a dramatic effect on receptor-mediated endocytosis. Cytochalasin D, an actin-disrupting drug, specifically affects the actin cytoskeleton by preventing its proper polymerization into microfilaments and promoting microfilament disassembly (20).

On the other hand, microtubules are required for efficient transcytosis and for trafficking endosomes to late endosomes and lysosomes. Nocodazole disrupts microtubules by binding to β-tubulin and preventing formation of one of the two interchain disulfide linkages, thus inhibiting microtubules dynamics (56). It appears noteworthy that the endocytic pathway for WNV is closely associated with host cells cytoskeleton network. As revealed by Percoll cell fractionation studies, the initial internalization of WNV that have attached to the plasma membrane was affected for Vero cells that were pretreated with cytochalasin D (Fig. 8). WNVs are predominantly detected in the plasma membrane fraction instead of the endosomal fraction, suggesting the early involvement of actin filaments in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. In contrast, the initial internalization of WNV via clathrin-coated pits was not affected with cells treated with nocodazole. However, WNV accumulated in endosomes and trafficking of the virus particles to lysosomes was deterred in nocodazole-treated cells (Fig. 8).

It is also notable that incubation of cells with lysosomotropic weak bases (chloroquine and amantidine) and vacuolar H+-ATPase (VATPase) inhibitor (bafilomycin) caused a marked reduction in the entry of WNV. This observation is consistent with a number of enveloped viruses that are currently considered to be pH dependent for the uncoating process along endocytic vesicles (30). For flaviviruses, it has been proposed that the structural domain II of the E protein require a pH-dependent fusion at the endocytic membranes. Mutational studies that disrupt the functional biology of this domain have shown a decrease in the virulence of these flaviviruses (36). A highly conserved amino acid cluster located at the tip of domain II has been proposed to be the internal fusion peptide. At the pH of fusion, the flavivirus E protein on the surface of the virus undergo irreversible conformational changes to expose the fusion peptide for interaction with the target membrane (24).

Ultrastructural analysis and immunofluorescence assays have indicated that the pH-dependent fusion of WNV E protein occurs predominantly within lysosomes. The fusion process of the WNV E protein with the lysosomal membrane was observed by using cryoimmunoelectron microscopy, and the uncoated nucleocapsid particles were then released into the cytoplasm in the vicinity of the ER (Fig. 2j). Thus far, entry studies of flaviviruses have not been able to visualize the presence of nucleocapsid particles in the cytoplasm after the release from endocytic vesicles. It has been suggested by Gollins and Porterfield (21) that the uncoated nucleocapsids undergo spontaneous dissociation upon exit into the cytoplasm due to the instability of capsid protein interactions. However, in the present study, the released nucleocapsids in the cytoplasm were imaged and identified for the first time. The released nucleocapsids were labeled with gold particles and were observed in close association with the lysosomes and ER region (Fig. 2j and 4f).

To confirm the specific location of the release WNV RNA genomes, in situ hybridization coupled with immunoelectron microscopy were used. The viral RNA genomes were found to localize in the proximity of ER region (Fig. 3). The signal required for the trafficking of the released viral RNA genome after uncoating to the ER is still not known. Additional studies are under way to elucidate this trafficking mechanism.

The entry pathway of WNV was mapped. WNV utilizes various cellular components to facilitate its trafficking to specific sites in the cell so that a successful infection can occur. Understanding the entry pathway of flavivirus can serve as an important platform for the future development of antiviral strategies and for the screening antiviral agents.

Acknowledgments

We thank Loy Boon Pheng for technical assistance.

This study was supported by a grant from the Biomedical Research Council (project 01/1/21/18/003).

REFERENCES

- 1.An, S. F., D. Franklin, and K. A. Flemming. 1992. Generation of digoxigenin-labeled double-stranded and single-stranded probes using the polymerase chain reaction. Mol. Cell Probes 6:193-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen, K. B., and B. A. Nexo. 1983. Entry of murine retrovirus into mouse fibroblasts. Virology 125:85-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartlett, J. S., R. Wilcher, and R. J. Samulski. 2000. Infectious entry pathway of adeno-associated virus and adeno-associated virus vectors. J. Virol. 74:2777-2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayer, N., D. Schober, M. Huttinger, D. Blaas, and R. Fuchs. 2001. Inhibition of clathrin-dependent endocytosis has multiple effects on human rhinovirus serotype 2 cell entry. J. Biol. Chem. 276:3952-3962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beasley, D. W., and A. D. Barrett. 2002. Identification of neutralizing epitopes within structural domain III of the West Nile virus envelope protein. J. Virol. 76:13097-13100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benmerah, A., C. Lamaze, B. Begue, S. L. Schmid, A. Dautry-Varsat, and N. Cerf-Bensussan. 1998. AP-2/Eps15 interaction is required for receptor-mediated endocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 140:1055-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benmerah, A., M. Bayrou, N. Cerf-Bensussan, and A. Dautry-Varsat. 1999. Inhibition of clathrin-coated pit assembly by an Eps15 mutant. J. Cell Sci. 112(Pt. 9):1303-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodsky, F. M., C. Y. Chen, C. Knuehl, M. C. Towler, and D. E. Wakeham. 2001. Biological basket weaving: formation and function of clathrin-coated vesicles. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17:517-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buss, F., J. P. Luzio, and J. Kendrick-Jones. 2001. Myosin VI, a new force in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. FEBS Lett. 508:295-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone, R., S. Fre, G. Iannolo, F. Belleudi, P. Mancini, P. G. Pelicci, M. R. Torrisi, and P. P. Di Fiore. 1997. Eps15 and Eps15R are essential components of the endocytic pathway. Cancer Res. 57:5498-5504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castle, E., and G. Wengler. 1987. Nucleotide sequence of the 5′-terminal untranslated part of the genome of the flavivirus West Nile virus. Arch. Virol. 92:309-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Castle, E., T. Nowak, U. Leidner, G. Wengler, and G. Wengler. 1985. Sequence analysis of the viral core protein and the membrane-associated proteins V1 and NV2 of the flavivirus West Nile virus and of the genome sequence for these proteins. Virology 145:227-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castle, E., U. Leidner, T. Nowak, G. Wengler, and G. Wengler. 1986. Primary structure of the West Nile flavivirus genome region coding for all nonstructural proteins. Virology 149:10-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chazal, N., and D. Gerlier. 2003. Virus entry, assembly, budding, and membrane rafts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67:226-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu, J. J. H., and M. L. Ng. 2002. Trafficking mechanism of West Nile (Sarafend) virus structural proteins. J. Med. Virol. 67:127-136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu, J. J. H., and M. L. Ng. 2003. Characterization of a 105-kDa plasma membrane associated glycoprotein that is involved in West Nile virus binding and infection. Virology 312:458-469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crill, W. D., and J. T. Roehrig. 2001. Monoclonal antibodies that bind to domain III of dengue virus E glycoprotein are the most efficient blockers of virus adsorption to Vero cells. J. Virol. 75:7769-7773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crimmins, D. L., W. B. Mehard, and S. Schlesinger. 1983. Physical properties of a soluble form of the glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus at neutral and acidic pH. Biochemistry 22:5790-5796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Durrbach, A., D. Louvard, and E. Coudrier. 1996. Actin filaments facilitate two steps of endocytosis. J. Cell Sci. 109(Pt. 2):457-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flanagan, M. D., and S. Lin. 1980. Cytochalasins block actin filament elongation by binding to high-affinity sites associated with F-actin. J. Biol. Chem. 255:835-838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gollins, S. W., and J. S. Porterfield. 1985. Flavivirus infection enhancement in macrophages: an electron microscopic study of viral cellular entry. J. Gen. Virol. 66(Pt. 9):1969-1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grief, C., R. Galler, L. M. Cortes, and O. M. Barth. 1997. Intracellular localization of dengue-2 RNA in mosquito cell culture using electron microscopic in situ hybridization. Arch. Virol. 142:2347-2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gruenberg, J. 2001. The endocytic pathway: a mosaic of domains. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2:721-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heinz, F. X., and S. L. Allison. 2001. The machinery for flavivirus fusion with host cell membranes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:450-455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinz, F. X., G. Auer, K. Stiasny, H. Holzmann, C. Mandl, F. Guirakhoo, and C. Kunz. 1994. The interactions of the flavivirus envelope proteins: implications for virus entry and release. Arch. Virol. 9(Suppl.):339-348. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Helenius, A. 1995. Alphavirus and flavivirus glycoproteins: structures and functions. Cell 81:651-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Helenius, A., J. Kartenbeck, K. Simons, and E. Fries. 1980. On the entry of Semliki Forest virus into BHK-21 cells. J. Cell Biol. 84:404-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jin, M., J. Park, S. Lee, B. Park, J. Shin, K. J. Song, T. I. Ahn, S. Y. Hwang, B. Y. Ahn, and K. Ahn. 2002. Hantaan virus enters cells by clathrin-dependent receptor-mediated endocytosis. Virology 294:60-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joki-Korpela, P., V. Marjomaki, C. Krogerus, J. Heino, and T. Hyypia. 2001. Entry of human parechovirus 1. J. Virol. 75:1958-1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kielian, M., and S. Jungerwirth. 1990. Mechanisms of enveloped virus entry into cells. Mol. Biol. Med. 7:17-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kornilova, E., T. Sorkina, L. Beguinot, and A. Sorkin. 1996. Lysosomal targeting of epidermal growth factor receptors via a kinase-dependent pathway is mediated by the receptor carboxyl-terminal residues 1022 to 1123. J. Biol. Chem. 271:30340-30346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krizanova, O., F. Ciampor, and P. Veber. 1982. Influence of chlorpromazine on the replication of influenza virus in chick embryo cells. Acta Virol. 26:209-216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McClure, M. O., M. Marsh, and R. A. Weiss. 1988. Human immunodeficiency virus infection of CD4-bearing cells occurs by a pH-independent mechanism. EMBO J. 7:513-518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McClure, M. O., M. A. Sommerfelt, M. Marsh, and R. A. Weiss. 1990. The pH independence of mammalian retrovirus infection. J. Gen. Virol. 71(Pt. 4):767-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michaely, P., A. Kamal, R. G. Anderson, and V. Bennett. 1999. A requirement for ankyrin binding to clathrin during coated pit budding. J. Biol. Chem. 274:35908-35913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monath, T. P., J. Arroyo, I. Levenbook, Z. X. Zhang, J. Catalan, K. Draper, and F. Guirakhoo. 2002. Single mutation in the flavivirus envelope protein hinge region increases neurovirulence for mice and monkeys but decreases viscerotropism for monkeys: relevance to development and safety testing of live, attenuated vaccines. J. Virol. 76:1932-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murray, J. M., J. G. Aaskov, and P. J. Wright. 1993. Processing of the dengue virus type 2 proteins prM and C-prM. J. Gen. Virol. 74(Pt. 2):175-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nawa, M. 1998. Effects of bafilomycin A1 on Japanese encephalitis virus in C6/36 mosquito cells. Arch. Virol. 143:1555-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nawa, M., T. Takasaki, K. Yamada, I. Kurane, and T. Akatsuka. 2003. Interference in Japanese encephalitis virus infection of Vero cells by a cationic amphiphilic drug, chlorpromazine. J. Gen. Virol. 84(Pt. 7):1737-1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ng, M. L. 1987. Ultrastructural studies of Kunjin virus-infected Aedes albopictus cells. J. Gen. Virol. 68(Pt. 2):577-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng, M. L., and J. J. H. Chu. 2002. Interaction of West Nile and Kunjin viruses with cellular components during morphogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 267:353-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ng, M. L., S. H. Tan, and J. J. H. Chu. 2001. Transport and budding at two distinct sites of visible nucleocapsids of West Nile (Sarafend) virus. J. Med. Virol. 65:758-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ng, M. L., S. H. Tan, E. E. See, E. E. Ooi, and A. E. Ling. 2003. Early events of SARS coronavirus infection in Vero cells. J. Med. Virol. 71:323-331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nussbaum, O., A. Roop, and W. F. Anderson. 1993. Sequences determining the pH dependence of viral entry are distinct from the host range-determining region of the murine ecotropic and amphotropic retrovirus envelope proteins. J. Virol. 67:7402-7405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pho, M. T., A. Ashok, and W. J. Atwood. 2000. JC virus enters human glial cells by clathrin-dependent receptor-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol. 74:2288-2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Punnonen, E. L., V. S. Marjomaki, and H. Reunanen. 1994. 3-Methyladenine inhibits transport from late endosomes to lysosomes in cultured rat and mouse fibroblasts. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 65:14-25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qualmann, B., and M. M. Kessels. 2002. Endocytosis and the cytoskeleton. Int. Rev. Cytol. 220:93-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rey, F. A., F. X. Heinz, C. Mandl, C. Kunz, and S. C. Harrison. 1995. The envelope glycoprotein from tick-borne encephalitis virus at 2 Å resolution. Nature 375:291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rice, C. M. 1996. Flaviviridae: the viruses and their replication, p. 931-959. In B. N. Fields, D. M. Knipe, and P. M. Howley (ed.), Fields virology, 3rd ed. Lippincott-Raven Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 50.Schneider-Schaulies, J. 2000. Cellular receptors for viruses: links to tropism and pathogenesis. J. Gen. Virol. 81(Pt. 6):1413-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sieczkarski, S. B., and G. R. Whittaker. 2002. Dissecting virus entry via endocytosis. J. Gen. Virol. 83(Pt. 7):1535-1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thilo, L., E. Stroud, and T. Haylett. 1995. Maturation of early endosomes and vesicular traffic to lysosomes in relation to membrane recycling. J. Cell Sci. 108:1791-1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thullier, P., C. Demangel, H. Bedouelle, F. Megret, A. Jouan, V. Deubel, J. C. Mazie, and P. Lafaye. 2001. Mapping of a dengue virus neutralizing epitope critical for the infectivity of all serotypes: insight into the neutralization mechanism. J. Gen. Virol. 82(Pt. 8):1885-1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tokuyasu, K. T. 1984. Immuno-cryoultramicrotomy, p. 71-82. In J. M. Polak and I. M. Varnell (ed.), Immunolabeling for electron microscopy. Elsevier Science, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 55.Umata, T., Y. Moriyama, M. Futai, and E. Mekada. 1990. The cytotoxic action of diphtheria toxin and its degradation in intact Vero cells are inhibited by bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 265:21940-21945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vasquez, R. J., B. Howell, A. M. Yvon, P. Wadsworth, and L. Cassimeris. 1997. Nanomolar concentrations of nocodazole alter microtubule dynamic instability in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Biol. Cell 8:973-985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watson, H. A., M. J. Cope, A. C. Groen, D. G. Drubin, and B. Wendland. 2001. In vivo role for actin-regulating kinases in endocytosis and yeast epsin phosphorylation. Mol. Biol. Cell 12:3668-3679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wengler, G., E. Castle, U. Leidner, T. Nowak, and G. Wengler. 1985. Sequence analysis of the membrane protein V3 of the flavivirus West Nile virus and of its gene. Virology 147:264-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wengler, G., G. Wengler, and H. J. Gross. 1978. Studies on virus-specific nucleic acids synthesized in vertebrate and mosquito cells infected with flaviviruses. Virology 89:423-437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Westaway, E. G., J. M. Mackenzie, and A. A. Khromykh. 2002. Replication and gene function in Kunjin virus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 267:323-531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshimori, T., A. Yamamoto, Y. Moriyama, M. Futai, and Y. Tashiro. 1991. Bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase, inhibits acidification and protein degradation in lysosomes of cultured cells. J. Biol. Chem. 266:17707-17712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zeichhardt, H., K. Wetz, P. Willingmann and K. O. Habermehl. 1985. Entry of poliovirus type 1 and Mouse Elberfeld (ME) virus into HEp-2 cells: receptor-mediated endocytosis and endosomal or lysosomal uncoating. J. Gen. Virol. 66(Pt. 3):483-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]