Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) UL84 is required for oriLyt-dependent DNA replication, and evidence from transient transfection assays suggests that UL84 directly participates in DNA synthesis. In addition, because of its apparent interaction with IE2, UL84 is implicated as a possible regulatory protein. To address the role of UL84 in the context of the viral genome, we generated a recombinant HCMV bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) construct that did not express the UL84 gene product. This construct, BAC-IN84/Ep, displayed a null phenotype in that it failed to produce infectious virus after transfection into human fibroblast cells, whereas a revertant virus readily produced viral plaques and, subsequently, infectious virus. Real-time quantitative PCR showed that BAC-IN84/Ep was defective for DNA synthesis in that no increase in the accumulation of viral DNA was observed in transfected cells. We were unable to complement BAC-IN84/Ep in trans; however, oriLyt-dependent DNA replication was observed by the cotransfection of UL84 and BAC-IN84/Ep. An analysis of viral mRNA by real-time PCR indicated that, even in the absence of DNA synthesis, all representative kinetic classes of genes were expressed in cells transfected with BAC-IN84/Ep. The detection of UL44 and IE2 by immunofluorescence in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells showed that these proteins failed to partition into replication compartments, indicating that UL84 expression is essential for the formation of these proteins into replication centers within the context of the viral genome. These results show that UL84 provides an essential DNA replication function and influences the subcellular localization of other viral proteins.

Originally, transient cotransfection replication assays identified 11 loci that are required for human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) oriLyt-dependent DNA replication (21, 22). Six of these loci contain homologues or probable homologues of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) replication genes encoding a DNA polymerase (UL54), a polymerase accessory protein (UL44), a single-stranded DNA-binding protein (UL57), a primase (UL70), a helicase (UL105), and a primase-associated factor (UL102) (18). Later studies showed that, in human fibroblasts, UL84, UL36-38, and the immediate-early protein IE2-580aa (referred to as IE2) were also necessary for the efficient amplification of oriLyt (26). However, when Epstein-Barr virus core replication proteins were used in Vero cells in place of HCMV core proteins (UL44, UL54, UL57, UL105, UL70, and UL102), UL84 was the only noncore protein that was necessary for oriLyt amplification. In contrast, another study using HSV-1 replication proteins showed that only IE2, not UL84, was necessary for HCMV oriLyt-dependent DNA replication (24). In our hands, in human fibroblasts, the gene products of both IE2 and UL84 are necessary for amplification of oriLyt.

Although many of the genes identified by cotransfection assays encode proteins that have a known or proposed function, to date UL84 has not been shown to directly participate in DNA synthesis or the initiation of DNA synthesis. UL84 localizes in DNA replication compartments in infected and transfected cells and appears to play a key role in promoting the formation of these replication compartments in transfected cells (26, 31). UL84 is classified as an early gene, and mRNA for UL84 can be detected as early as 2.5 h postinfection (11); however, the protein is not detected until 24 h postinfection (Y. Xu and G. S. Pari, unpublished data). In addition, UL84 interacts with HCMV IE2 at early times postinfection (28), and in transient assays this interaction down regulates the transactivation activity of IE2 on the promoter for the early genes encoded by UL112/113 (10). The overexpression of UL84 in U373 cells impeded HCMV growth in a transdominant manner (10). The ability of UL84 to affect the transactivation activity of IE2 suggests that UL84 may function in part as a unique regulatory protein by directly interacting with IE2 and possibly altering the activity of IE2 toward a proposed replication function.

To better understand the functional role of UL84 in the context of the viral genome, we generated a UL84 insertion mutant of HCMV (BAC-IN84/Ep) by using bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) technology. BAC technology is a recently developed approach for the construction of herpesvirus recombinants. This approach is based on cloning of the virus genome as a BAC in Escherichia coli (27). With either F-factor-derived BAC or bacteriophage P1 replicon-based (PAC) cloning systems (12), maintenance of foreign DNAs of ∼300 kb has been achieved. BACs are easy to handle and have proved to be remarkably stable (13, 27). Several recent reports have established the utility of BAC clones of herpesvirus genomes for the production and purification of genomes containing defined mutations. BAC clones have now been described for HSV-1, pseudorabies virus, varicella-zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and human and murine CMV (6).

In this report, we show that an insertion mutation within the UL84 open reading frame (ORF) is lethal to viral growth and DNA replication. The transfection of BAC-IN84/Ep into permissive fibroblasts failed to produce infectious virus, whereas a revertant virus displayed wild-type (wt) growth kinetics. A real-time PCR analysis of the viral DNA showed that no viral DNA amplification was detected for up to 21 days posttransfection for BAC-IN84/Ep, whereas a wt HCMV BAC resulted in a marked increase in viral DNA accumulation. Repeated attempts to complement viral growth by supplying UL84 in trans failed; however, we were able to complement oriLyt-dependent DNA replication by cotransfection of a UL84 expression construct along with HCMV-cloned oriLyt. A real-time PCR analysis of viral transcripts revealed that, despite the absence of DNA synthesis, all kinetic classes of genes were expressed in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells. Cells transfected with BAC-IN84/Ep also showed an aberrant level of late gene transcripts at immediate-early times compared to transcript levels from wt HCMV BAC-transfected cells. Immunofluorescence detection of IE2 and UL44 in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells showed that these two proteins failed to partition into nuclear replication compartments. These data suggest that UL84 has a direct role in DNA replication and is instrumental in directing components of the viral replication machinery to replication centers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

Human foreskin fibroblast (HFF) cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. HCMV strain AD169 (American Type Culture Collection) was maintained as frozen stocks.

Plasmids.

The replication reporter pGEM-orilyt, which was described previously (31), contains the 5-kb PvuII-KpnI HCMV oriLyt fragment (nucleotides 89796 to 94860 of AD169) (7) ligated into pGEM-7Zf(−) (Promega). A UL84 expression plasmid, pZP13, containing full-length UL84 with its native promoter, was constructed as previously described (21). The enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP)-puromycin cassette was described previously (1).

Plasmids for BAC mutagenesis.

The HCMV BAC plasmid pHB5 in E. coli strain DH10B and the shuttle plasmid pST76K_SR were obtained from M. Messerle, Max von Pettenkofer Institute, Munich, Germany (5).

For UL84 insertion BAC mutagenesis, plasmid ZP10 (21) was cleaved with XhoI to release a 9.4-kb fragment containing the UL84 ORF and its flanking sequence (nucleotides 117490 to 126860 of AD169) (7). This fragment was then ligated into the pBlueScript II SK (−) vector (Stratagene) cleaved with XhoI to create pBS-UL84. pBS-UL84 was cleaved with MunI in the middle of the UL84 ORF and then treated with the E. coli DNA polymerase Klenow fragment to generate blunt ends. An EGFP-puromycin fusion protein expression cassette (1) was ligated into the blunt-ended MunI site. The resultant plasmid, pBS-IN84/Ep, was then cleaved with KpnI to release an 11.2-kb fragment containing the EGFP-puromycin cassette flanked by about 4.5 kb of UL84 flanking sequence at both sites. This released fragment was then ligated into pST76K_SR cleaved with KpnI. The final construct, pKSR-IN84/Ep, was then used as a shuttle vector to create a BAC mutant with the UL84 gene locus interrupted.

For construction of the UL84 revertant BAC, pBS-UL84 was cleaved with KpnI to release the 9.2-kb fragment containing the full-length UL84 ORF and its flanking sequence. The fragment was ligated into pST76K_SR that had been cleaved with KpnI. The resultant plasmid, pKSR_UL84, was then used to construct the BAC revertant.

BAC mutagenesis.

Mutagenesis of the HCMV BAC plasmid was performed according to a protocol provided by M. Messerle. Briefly, the shuttle plasmid pKSR-IN84/Ep was electroporated into E. coli DH10B bacteria that already contained the HCMV BAC plasmid. Transformants were selected at 30°C on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates containing chloramphenicol (15 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml). Clones containing cointegrates were identified by streaking the bacteria onto new LB plates containing chloramphenicol (15 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml), followed by incubation at 43°C. To allow for resolution of the cointegrates, we streaked the clones onto LB plates containing chloramphenicol (15 μg/ml) and incubated them at 30°C. To select for clones that had resolved the cointegrate and that contained the mutant BAC plasmid, we restreaked bacteria onto LB plates containing chloramphenicol (15 μg/ml) and 5% sucrose. Resolution of the cointegrate was confirmed by testing for the loss of the kanamycin marker encoded by the shuttle plasmid. BAC plasmid DNA was isolated from 10-ml overnight cultures by an alkaline lysis procedure (15) and was characterized by restriction enzyme analysis followed by Southern blot analysis. Large preparations of HCMV BAC plasmids were obtained from 250-ml E. coli cultures by use of a Nucleobond BAC maxi kit (BD Biosciences Clontech) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Reconstitution of HCMV BAC virus.

For each transfection, 4 × 106 actively dividing HFF cells were trypsinized, suspended in 0.5 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 10% fetal bovine serum, and mixed with 5 μg of HCMV BAC plasmid DNA, 1 μg of pcDNApp71tag, which encodes the HCMV tegument protein pp71 (the pp71 expression plasmid pcDNApp71tag was constructed and kindly provided by B. Plachter, University of Mainz, Mainz, Germany), and 50 μl of 10-mg/ml sheared salmon sperm DNA in a 0.4-cm-gap cuvette. After electroporation at 200 V and 1,600 μF, the cells were plated into 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks. After transfection, the cells were propagated in a normal culture medium for 3 to 4 days. The cells were then split (1:3) and cultivated until plaques appeared. The supernatants of these cultures were used to infect new cells for the preparation of virus stocks.

Southern blot analysis.

DNA probes for Southern blot hybridizations were excised from plasmids by the use of appropriate restriction enzymes and were purified from agarose gels as follows: probe 1 was isolated as a 900-bp SalI-NheI fragment from the EGFP-puromycin cassette, and a 400-bp SalI-MunI fragment from the native UL84 expression plasmid pZP13 (21) specific for the UL84 ORF was used as probe 2. Purified HCMV BAC plasmid DNAs were cleaved with the appropriate restriction enzymes and separated by electrophoresis in 0.5% agarose gels in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer for 14 to 18 h at 2.5 V/cm. DNA fragments were visualized by ethidium bromide staining, denatured, and transferred to Zeta-Probe GT genomic-tested blotting membranes (Bio-Rad). DNA probes were radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP (Amersham) by use of the Rediprime II random prime labeling system (Amersham). Prehybridization was performed at 65°C for 1 h in hybridization buffer (7% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10% polyethylene glycol, 1.5× SSPE [1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaPO4, and 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.7]). DNA blots were hybridized with radiolabeled probes in the same solution at 65°C for about 16 h. The blots were washed twice for 15 min with 2× SSC-0.1% SDS (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate) and twice for 30 min with 0.1× SSC-0.1% SDS at 65°C. The blots were exposed to X-ray film for 3 to 5 h at room temperature.

Virus growth curves.

HFF cells (2 × 105 /well) seeded in a 12-well dish were infected with the virus at a multiplicity of infection of 5 PFU/cell. The supernatants were harvested at 24-h intervals for up to 6 days postinfection. Viral titers were determined by plaque assays (23). Assays were done in triplicate for each time point.

oriLyt transient replication assay.

HFF cells (4 × 106) were transfected with 10 μg of purified HCMV BAC DNA along with 5 μg of pGEM-orilyt and with or without 1 μg of the UL84-carrying plasmid (pZP13) by electroporation as described above. Transfected cells were incubated for 8 days, at which time the total cellular DNA was extracted. The DNA was cleaved with DpnI and EcoRI, and amplification of the cloned oriLyt plasmid was analyzed as described previously (21).

Fluorescence microscopy for BAC-IN84/Ep transfection efficiency.

HFF cells were transfected with BAC-IN84/Ep DNA by electroporation as described above. Transfected cells were plated on glass coverslips, fixed at 96 h posttransfection (hpt) with 1% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min at 20°C, and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min at 4°C. The coverslips were rinsed three times in PBS and then incubated with Hoechst 33342 staining solution (Molecular Probes, Inc.) for 5 min to stain the cell nucleus. The cells were rinsed with PBS and mounted. Images were captured with a Nikon E800 epifluorescence microscope using a 20× objective. Live cell images of viral plaques were captured with a 10× objective and a Nikon Eclipse E200 microscope.

Immunofluorescence assay.

Transfected cells were plated on glass coverslips, fixed at 96 hpt with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at 20°C, and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 20 min at 4°C. The cells were rinsed with PBS, incubated with 10% goat serum for 20 min, and then rinsed again with PBS. The coverslips were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in a humidified tray with 2% goat serum and a 1:200 dilution of primary antibody. After incubation, the coverslips were washed in PBS three times for 5 min each and then incubated with a 1:400 dilution of an Alexa fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin antibody (Molecular Probes, Inc.) for 45 min at 37°C. The cells were again washed in PBS three times for 5 min each and then were incubated with Hoechst 33342 staining solution for 5 min. Prior to the addition of mounting solution, the cells were once again washed in PBS three times for 5 min each. Images were captured with a Nikon E800 epifluorescence microscope using a 100× oil immersion objective. Detection of the HCMV IE2 protein was done with the anti-HCMV IE2 mouse monoclonal antibody G13-12E2 (Vancouver Biotech, Ltd.). Detection of the HCMV UL44 protein was done with an anti-HCMV UL44 mouse monoclonal antibody (Advanced Biotechnologies Inc.).

RNA purification.

HFF cells (4 × 106) were transfected with 5 μg of purified BAC DNA, 1 μg of pcDNApp71tag, and 50 μl of 10-mg/ml sheared salmon sperm DNA and electroporated as described above. Samples were harvested at various times posttransfection. Total RNAs were isolated with an Absolutely RNA RT-PCR miniprep kit (Stratagene) used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Residual DNA contamination was eliminated by the use of TURBO DNA-free DNase (Ambion). DNA contamination was tested by reverse transcription-PCR using a set of IE2 primers spanning IE2 intron 3. RNA quality was assessed by the separation of RNAs through a 1% formaldehyde denaturing agarose gel. Only samples with 260/280-nm absorbance ratios of >1.9 were used for subsequent experiments.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis.

cDNAs (20 μl) for real-time PCR were generated from 2-μg samples of total RNA by use of the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen), primed with 250 ng of random hexamers, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Probe and primer sequences for the real-time TaqMan PCR system were chosen for the IE2, TRS1, UL44, UL105, UL75, UL83, and UL84 genes and were synthesized with an Applied Biosystems Assay-by-Design program (Table 1). The two unlabeled PCR primers and the FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) dye-labeled TaqMan MGB probe for each sequence were formulated into a single-tube, ready-to-use mixture at a 20× concentration. Real-time PCRs were performed with a TaqMan Universal PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems), which consists of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, a 300 mM (each) dATP, dCTP, and dGTP, 600 mM dUTP, 0.625 U of AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase per reaction, and 0.25 U of uracil N-glycosylase per reaction. Reactions in a total volume of 25 μl consisted of 12.5 μl of master mix, appropriate amounts of cDNA (10% for the detection of viral transcripts and 2% for the detection of cellular transcripts), a 900 nM concentration of each primer, and 200 nM TaqMan probe. After 2 min at 50°C, the AmpliTaq Gold DNA polymerase was activated at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. All reactions were carried out in triplicate in an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector (Applied Biosystems).

TABLE 1.

Primers and probes used for real-time PCR

| Gene | Primer direction or probe indication | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| IE2 | Forward | TGGCAGAACTCGGTGACATC |

| Reverse | GCTGCGGAAGTGGGTTGT | |

| Probe | AGGCTGTCAATCATGCCGGTATCGATTC | |

| TRS1 | Forward | CTGTGCAAATGTGGAAGACTACCT |

| Reverse | GTCCAGTCCCAGAGCTTGAG | |

| Probe | CAAGACGCCCGACGCC | |

| UL44 | Forward | GCCCGATTTCAATATGGAGTTCAG |

| Reverse | CGGCCGAATTCTCGCTTTC | |

| Probe | ACGGCCAAGACATTGT | |

| UL105 | Forward | GGACGCCGAACTCATGGA |

| Reverse | AGGTGGCTTGACGTATTTGAGAA | |

| Probe | CACACCAGTCTGTACGCGGATCCCTT | |

| UL75 | Forward | CGGGCGACGCGATCA |

| Reverse | CGGGAACGGTAGCAGGAA | |

| Probe | CTCGCTCGAACGCCTC | |

| UL83 | Forward | GCGCACGAGCTGGTTTG |

| Reverse | TGGTCACCTATCACCTGCATCT | |

| Probe | TCCATGGAGAACACGCGCGC | |

| UL84 | Forward | CTACGCCGCTGCAATTGG |

| Reverse | GCCGCCGTTTCTTCTTCTTG | |

| Probe | ACTCGTCGTTCGCTTCC |

RNAs isolated from Ad169-infected cells were used to generate a standard curve for each gene examined. The standard curves were used to calculate the relative amounts of specific cDNAs in the samples. Each transfection was performed in triplicate, and error bars in the figures show the standard deviations from the means for the three experiments. Data are reported as fold inductions over the mRNA levels from cells transfected with wt BAC at 1 day postelectroporation. As a negative control, each plate contained a minimum of three wells that lacked a template. Also, RNA from untransfected HFF cells was harvested and used as a mock control. As an additional control, the RNA from each sample, without the reverse transcriptase step, was analyzed by real-time PCR to ensure that the samples were free of contaminating DNAs.

Normalization of transfected viral genomes and mRNA levels.

Data for each sample were normalized to human cyclophilin (Applied Biosystem) levels to ensure that equal amounts of cDNA input were used for real-time PCRs. In addition, the total DNA harvested from transfected cells at 1 day postelectroporation was also analyzed by real-time PCR and used to normalize for differences in the transfection efficiencies of wt and BAC-IN84/Ep DNAs. In addition, transfected cells were incubated with a monoclonal antibody specific for IE1/IE2, and fluorescent cells were scored and compared to the real-time PCR data for viral DNA at 1 day postelectroporation. The transfection efficiencies for both wt and mutant BACs were determined to be similar.

Viral DNA accumulation analysis by real-time PCR.

Reactions were done as described for cDNA real-time PCRs, with the exception that the total cellular DNA was used from samples that were transfected with either wt HCMV BAC or BAC-IN84/Ep. The cells were harvested at various times postelectroporation by the use of DNA extraction buffer (2% SDS, 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8], 10 mM EDTA, and 50 mg of proteinase K/ml). The cell lysates were incubated at 60°C for 1 h, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and then chloroform extraction. The DNA was precipitated with 100% ethanol. The DNA was resuspended in TE (10 mM Tris [pH 8], 1 mM EDTA), and the concentration was determined with a spectrophotometer. Equal amounts (100 ng) of the total DNA were used in real-time PCRs using primers and a probe specific for the UL105 locus. Each experiment was done in triplicate. A standard curve was generated with HCMV-infected cell DNA by use of the UL105 primers and probe.

RESULTS

Construction of a UL84 insertion mutation in HCMV BAC.

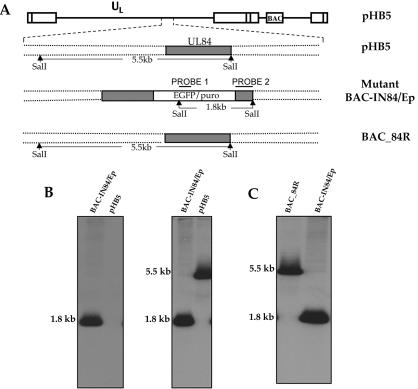

It was shown previously that UL84 is necessary for HCMV origin-dependent DNA replication (22, 26). To further investigate the function of UL84 in HCMV replication in the context of the virus genome, we constructed a UL84 insertion mutant by using the wt HCMV BAC (5) as the parental construct and inserting the EGFP-puromycin cassette (1) into the MunI (nucleotide 123,595) site of the UL84 ORF. The desired mutation was introduced by homologous recombination into E. coli by using plasmid pKSR-IN84/Ep and the BAC plasmid pHB5 as described in Materials and Methods (Fig. 1A). The mutant BAC-IN84/Ep and parental BAC pHB5 plasmids were analyzed by SalI digestion followed by Southern blot hybridization with a DNA probe generated from the EGFP-puromycin cassette (Fig. 1A, probe 1). As predicted, a 1.8-kb band was detected for the mutant BAC-IN84/Ep but no band was detected for the wt pHB5 BAC (Fig. 1B, left panel). To further confirm the correct insertion of the EGFP-puromycin cassette, we again cleaved both the wt BAC and the mutant BAC with SalI and hybridized the blots with a fragment specific for the UL84 ORF (Fig. 1A, probe 2). The predicted 1.8-kb band was observed for the mutant BAC-IN84/Ep sample, while for the pHB5 DNA, a 5.5-kb band was detected (Fig. 1B, right panel).

FIG. 1.

Generation of BAC-IN84/Ep. (A) Schematic of wt HCMV BAC pHB5 with the genomic region encoding UL84, the mutant BAC-IN84/Ep, showing the location of the insertion of an EGFP-puromycin expression cassette, and the revertant BAC_84R. The predicted sizes from cleavages with SalI are shown. Also shown are the positions of hybridization probes used for Southern blots. (B) Southern blot of wt HCMV BAC pHB5 and mutant BAC-IN84/Ep. (Left) BAC clones cleaved with SalI and hybridized with probe 1; (Right) BAC clones cleaved with SalI and hybridized with probe 2. (C) Generation of UL84 revertant BAC (BAC_84R). The Southern blot shows the mutant BAC-IN84/Ep and revertant BAC_84R cleaved with SalI and hybridized with probe 2.

A UL84 revertant BAC was generated by using the plasmid pKSR_UL84, which encoded the full-length UL84 gene and its flanking sequence. Homologous recombination was carried out in E. coli by using the pKSR_UL84 plasmid, with the mutant BAC-IN84/Ep as the parental BAC, to reinsert the UL84 locus. The UL84 revertant BAC_84R and the mutant BAC-IN84/Ep were then cleaved with SalI, and Southern blot hybridization was performed with probe 2 (Fig. 1A), which hybridizes to the UL84 ORF. Southern blot analysis confirmed that the UL84 gene was reinserted in BAC_84R (Fig. 1C).

UL84 is essential for viral growth.

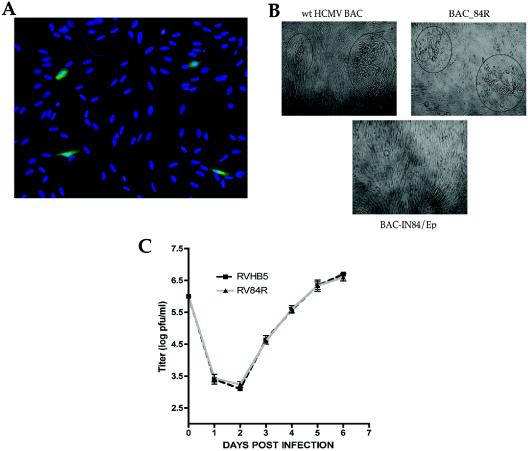

Once a recombinant BAC was made, we next wanted to determine if this new virus mutant was viable. To generate reconstituted viruses, we electroporated purified wt BAC pHB5, BAC-IN84/Ep, and BAC_84R DNAs into permissive HFF cells. Transfection efficiencies were monitored by measuring the EGFP expression level originating from the mutant BAC-IN84/Ep. Transfection of the mutant BAC-IN84/Ep into HFFs led to the formation of single green fluorescent cells (Fig. 2A). Further incubation of the BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells did not lead to plaque formation, even after 21 days of incubation. The transfections were repeated several times with multiple BAC DNA preparations to minimize the chance that negative results were caused by defects in the BAC DNA introduced during passage in E. coli or during DNA preparation. In contrast to the result with the mutant BAC, transfection of the wt pHB5 BAC and revertant BAC_84R gave rise to viral plaques and infectious virus after 7 to 10 days in culture (Fig. 2B, circled plaques). In order to test that the growth kinetics of the revertant virus were restored to those of the wt, we generated a growth curve for each virus. Cells were infected with each virus (wt and revertant), and the viruses were harvested on various days postinfection. Infectious virus titers were determined by plaque assays (Fig. 2C). Both wt and revertant viruses displayed similar growth kinetics, confirming that the interruption of the UL84 gene gave rise to the growth-defective phenotype of BAC-IN84/Ep.

FIG. 2.

BAC-IN84/Ep does not produce viral plaques or infectious virus. (A) Electroporation of HFFs with BAC-IN84/Ep shows the appearance of green cells at 96 hpt. The transfection efficiency was monitored by measuring EGFP expression by fluorescence microscopy. (B) HFFs were electroporated with either BAC-IN84/Ep, wt HCMV BAC, or revertant BAC (BAC-84R). The cells were incubated for 8 days and then visualized by light microscopy. wt HCMV BAC- and BAC-84R-transfected cells showed typical viral plaques, whereas BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells failed to show any plaque formation. Viral plaques are shown within circled regions. (C) Single-step growth curves of reconstituted wt HCMV BAC virus (RVHB5) and revertant BAC virus (RV84R). Supernatant virus was harvested from cells electroporated with revertant BAC or wt HCMV BAC DNA. The resultant virus, RVHB5 (wt HCMV BAC) or RV84R (UL84 revertant BAC), was harvested and used to infect fresh HFFs. The supernatants from infected cells were collected on various days postinfection, and viral titers were determined by standard plaque assays. Error bars are the standard deviations from the average titers of three separate experiments.

BAC-IN84/Ep is defective for DNA replication.

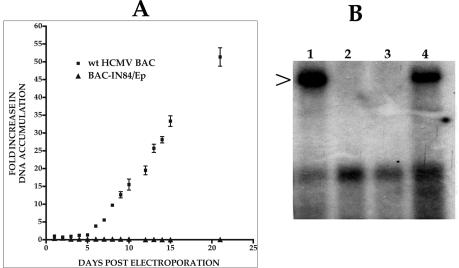

Since BAC-IN84/Ep failed to produce visible plaques or infectious virus, we investigated whether there was an increase in the accumulation of BAC-IN84/Ep viral DNA in transfected cells by using real-time PCR. We used this method to determine if the nature of the null phenotype observed for BAC-IN84/Ep with respect to the lack of virus production could possibly be due to defects in viral packaging or viral egress. HFFs were transfected with either wt HCMV BAC or BAC-IN84/Ep DNA, and the total cellular DNA was harvested at various times posttransfection. Viral DNA accumulation was measured and plotted as the relative fold increase in viral DNA accumulation over time after transfection. The wt viral DNA was shown to accumulate as much as 50-fold (compared to the input DNA, measured at 24 h postelectroporation) over the 21-day measurement period (Fig. 3A). However, BAC-IN84/Ep DNA remained constant, at about the same value as the input transfected DNA (Fig. 3A). This result suggested that BAC-IN84/Ep was defective for DNA replication, as no accumulation of viral DNA was detected for up to 3 weeks in cell culture.

FIG. 3.

BAC-IN84/Ep is defective for DNA replication. (A) Evaluation of viral DNA accumulation from wt HCMV BAC- or BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells. HFFs were electroporated, and total cellular DNAs were extracted on various days posttransfection and assayed for viral DNA accumulation by real-time PCR. The data are presented as fold increases in viral DNA accumulation over the amount of input DNA (day 1). Error bars are standard deviations for three separate experiments. (B) BAC-IN84/Ep can complement oriLyt-dependent DNA replication in the presence of UL84. The wt HCMV BAC pHB5 or mutant BAC-IN84/Ep was transfected into HFFs by electroporation along with HCMV oriLyt and with or without a plasmid encoding UL84. DNAs were extracted at 8 days posttransfection, cleaved with EcoRI and DpnI, transferred to a nylon membrane, and hybridized with pGEM-7Zf(−) (the parental vector of HCMV oriLyt). Lanes: 1, pHB5 cotransfected with oriLyt; 2, pHB5 cotransfected with pGEM-7Zf(−); 3, BAC-IN84/Ep cotransfected with oriLyt (no UL84); 4, BAC-IN84/Ep cotransfected with oriLyt and a plasmid encoding UL84 (ZP13). The arrow indicates the replicated, DpnI-resistant oriLyt plasmid.

BAC-IN84/Ep fails to complement HCMV oriLyt-dependent DNA replication.

Since real-time PCR showed that BAC-IN84/Ep was defective for DNA replication, we tried several methods to complement the growth of the mutant virus. The transfection of BAC-IN84/Ep into UL84-expressing cell lines or the transient transfection of UL84 expression constructs failed to complement BAC-IN84/Ep with respect to the production of infectious virus (data not shown). Because of these failed attempts to complement viral growth, we investigated whether the transient cotransfection of plasmids encoding UL84 along with BAC-IN84/Ep and the HCMV-cloned oriLyt would result in the amplification of oriLyt in transfected cells. This would suggest that the expression of UL84 in trans is sufficient to complement DNA replication but not sufficient for the complementation of viral growth. The wt HCMV BAC pHB5 or mutant BAC-IN84/Ep was transfected into HFFs along with a plasmid containing HCMV oriLyt and with or without a plasmid encoding UL84 (pZP13). BAC-IN84/Ep transfection along with oriLyt failed to produce any amplification products (Fig. 3B, lane 3). However, when pZP13 was included in the cotransfection, oriLyt replication products were detected (Fig. 3B, lane 4). In addition, the wt BAC was capable of providing the necessary transacting factors to amplify oriLyt (Fig. 3B, lane 1). This result is consistent with previous reports that UL84 is essential for the DNA replication of HCMV in transient cotransfection assays (21, 26) but also indicates that UL84 may regulate other viral events that are independent of DNA replication, since supplying UL84 in trans still failed to complement viral growth.

All representative kinetic classes of viral genes are expressed in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells.

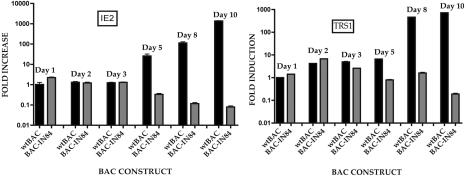

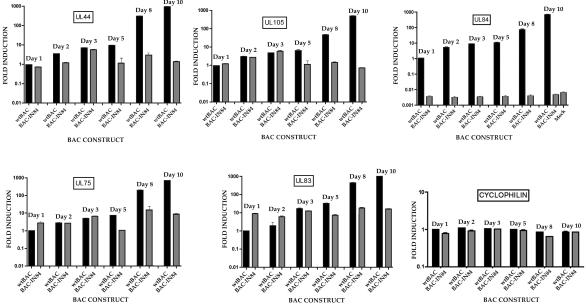

Since the UL84 insertion mutation was lethal to viral growth and failed to complement HCMV oriLyt-dependent DNA replication, we chose to examine the transcript levels in BAC-IN84/Ep- and wt BAC-transfected cells over a 10-day period posttransfection. HFFs were electroporated with wt or mutant BAC DNA, and RNA was extracted at 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, and 10 days posttransfection. Relative mRNA levels were measured by using primers and probes for various kinetic classes of viral genes (Table 1).

IE2 mRNA levels in BAC-IN84/Ep were equal to those observed for the wt BAC for up to 3 days posttransfection, except for a small increase (twofold) in mRNA levels at 1 day posttransfection (Fig. 4). At about 5 days posttransfection, concomitant with the spread of infectious virus (Fig. 3A), IE2 levels for wt BAC increased, whereas BAC-IN84/Ep IE2 transcript levels started to decrease between 5 and 10 days posttransfection (Fig. 4). This indicated that the increased accumulation of IE2 mRNA was fueled by the increase in the amount of DNA template in the wt HCMV BAC-transfected cells. The mRNA levels of the immediate-early gene terminal repeat sequence 1 (TRS1) in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells mirrored those observed in wt HCMV BAC-transfected cells within the first 3 days postelectroporation. However, as with the IE2 mRNA levels, TRS1 mRNA accumulation decreased to minimal levels (<10-fold over that observed on day 1) by day 10 postelectroporation (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Immediate-early gene expression patterns for BAC-IN84/Ep- and wt HCMV BAC-transfected cells. HFFs were electroporated with either BAC-IN84/Ep or wt HCMV BAC DNA, and the total cellular RNA was harvested on various days posttransfection and analyzed by real-time PCR. Real-time PCR primers and probes specific for IE2 or TRS1 were used to evaluate relative mRNA levels. The data are presented as fold increases over the mRNA levels measured on day 1 postelectroporation for the wt HCMV BAC. Error bars are the standard deviations from the averages of three separate experiments.

We also measured mRNA levels for two early genes involved in DNA replication, specifically UL44 (polymerase accessory protein) and UL105 (helicase) (21, 22). The wt and BAC-IN84/Ep mRNA levels for UL44 were similar through the first 3 days of transfection (Fig. 5). Both BAC-IN84/Ep and wt UL44 mRNA levels increased at day 3 posttransfection, but at day 5 posttransfection, the UL44 mRNA level for the wt HCMV BAC increased about 10-fold over BAC-IN84/Ep mRNA levels (Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained for the expression levels of the UL105 gene. The mRNA levels for UL105 from BAC-IN84/Ep and wt HCMV BAC were approximately the same until the onset of viral DNA synthesis at about 2 days posttransfection and the spread of infectious virus at about 5 days posttransfection (Fig. 5). In contrast to the results obtained with IE2, the transcript levels for both UL44 and UL105 at 10 days posttransfection remained at approximately the same level as that observed at day 1 postelectroporation, indicating that the viral DNA persisted and was still viable with respect to gene expression (Fig. 5). We also measured mRNA levels for UL84 in wt HCMV BAC- as well as BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells. As expected, UL84 mRNA in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells was considered to be absent, since the levels were similar to those observed for mock-infected cells (Fig. 5). Primers and probes for various regions of the remaining UL84 ORF in BAC-IN84/Ep showed that no portion of the UL84 gene was expressed (data not shown). The UL84 mRNA level in wt HCMV BAC-transfected cells increased steadily over the 10-day survey and correlated with the onset of DNA synthesis and subsequent accumulation of viral DNA from the spread of infectious virus (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Early and late mRNAs are expressed in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells. HFFs were electroporated with either BAC-IN84/Ep or wt HCMV BAC DNA, and the total cellular RNA was harvested on various days posttransfection and analyzed for early (UL44, UL105, and UL84), early-late (UL83), and late (UL75) gene expression by real-time PCR. The data are presented as fold increases over the mRNA levels measured on day 1 postelectroporation for the wt HCMV BAC. Also shown is a quantitative analysis of cyclophilin mRNA as a control to ensure that equal amounts of cDNA were added to the reaction mixtures. Error bars are the standard deviations from the averages of three separate experiments.

Late (UL75) and early-late (UL83) gene expression was also measured in wt HCMV BAC- or BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells. The UL75 gene encodes the envelope glycoprotein H, which shows late gene kinetics (17, 19, 33), and the early-late gene UL83 encodes the lower matrix phosphoprotein pp65 and has been shown to have delayed early or early-late kinetics of expression (20, 25). The transcript levels for both the UL83 and UL75 genes in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells were 5- to 10-fold higher than those observed for the wt BAC on day 1 posttransfection, suggesting that some dysregulation of late gene expression occurred in BAC-IN84/Ep (Fig. 5). This anomaly became less pronounced at days 2 and 3 posttransfection, but the levels of UL75 and UL83 in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells remained high for up to 10 days posttransfection (Fig. 5). The mRNA levels of UL83 and UL75 from wt HCMV BAC-transfected cells increased in conjunction with the onset of viral DNA replication (Fig. 5).

These results indicate that BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells continue to express early and late genes for up to 10 days posttransfection, suggesting that the lack of UL84 in the viral genome does not negatively effect the regulation of gene expression with respect to these two classes of genes. However, some aberrant gene expression was observed at earlier times posttransfection, which primarily affected the accumulation of late transcripts.

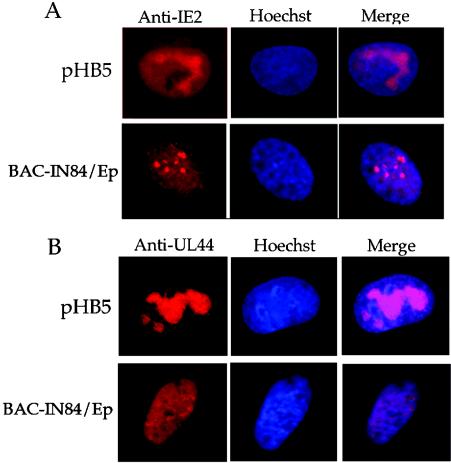

HCMV UL44 and IE2 fail to partition into replication compartments in cells transfected with BAC-IN84/Ep.

It was shown previously, by use of transient cotransfection assays, that UL84 localizes to DNA replication compartments in infected and transfected cells and that it is essential for promoting oriLyt-dependent DNA replication and the formation of replication compartments (26, 31). Since IE2 and UL44 are known to partition into HCMV DNA replication compartments in infected and transfected cells (4, 31), we decided to investigate the subcellular locations of these two protein products in BAC-IN84/Ep- or wt HCMV BAC-transfected cells. Purified BAC-IN84/Ep or wt HCMV BAC DNA was transfected into HFF cells, and immunofluorescence assays were performed at 96 hpt with an antibody specific for IE2 or UL44 and a secondary antibody conjugated with Alexa fluor 555. Transfected cells were also treated with Hoechst stain to identify the cell nucleus. As shown in Fig. 6, both IE2 and UL44 expressed from the wt HCMV BAC formed globular structures within the cell nucleus, consistent with the presence of replication compartments (2-4, 8, 14), while the immunofluorescence pattern for IE2 from BAC-IN84/Ep displayed small punctate structures and did not form organized nuclear structures resembling replication compartments (Fig. 6A). UL44 protein immunofluorescence patterns were very diffuse within the nucleus and also failed to coalesce into any recognizable globular structures in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells (Fig. 6B). This result confirmed that UL84 was essential for replication compartment formation and that the absence of UL84 expression resulted in the failure of UL44 and IE2 to partition into replication compartments.

FIG. 6.

Replication protein UL44 and immediate-early protein IE2 fail to partition into replication compartments in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells. An immunofluorescence assay was performed on HFFs transfected with the wt pHB5 BAC or BAC-IN84/Ep at 96 hpt. Transfected cells were incubated with an anti-IE2 or anti-UL44 antibody and an Alexa fluor 555-conjugated secondary antibody, as shown in red. Hoechst stain was used to identify the nuclei of transfected cells, which are shown in blue. (A) Incubation with anti-IE2-specific antibody in either pHB5 (top)- or BAC-IN84/Ep (bottom)-transfected cells. (B) Incubation with anti-UL44-specific antibody in either pHB5 (top)- or BAC-IN84/Ep (bottom)-transfected cells.

DISCUSSION

Typically, the initiation of lytic replication for herpesvirus DNA involves a viral protein that specifically recognizes a cis-acting sequence within oriLyt. For HCMV, it appears that the mechanism for the initiation of DNA synthesis may be more complex than those for other herpesvirus systems. To date, the only unique protein implicated in HCMV lytic DNA replication is UL84. Despite the discovery more than 10 years ago of the requirement of this protein for the amplification of oriLyt in transient assays, the exact function of the protein has yet to be elucidated. UL84 does not resemble or have any identifiable sequence homology to any other herpesvirus protein. It is assumed, however, that UL84 is the equivalent of an initiator or origin-binding protein. This is based on the observation that UL84 is absolutely necessary for oriLyt amplification in transient transfection assays. As valuable as transient transfection assays are, we sought to go beyond their limitations and to investigate the ability of a recombinant virus to replicate and grow in the absence of UL84 expression. In this study, we constructed a recombinant HCMV BAC, BAC-IN84/Ep, with an insertion in the UL84 gene locus. This mutant BAC was nonviable, in that no infectious virus, plaque formation, or accumulation of viral DNA was observed in transfected cells, whereas a revertant virus readily formed viral plaques and produced viral titers similar to those obtained with the wt HCMV BAC. In addition, BAC-IN84/Ep was unable to complement the replication of the HCMV oriLyt, whereas the wt HCMV BAC provided the necessary factors to amplify oriLyt. However, the addition of a plasmid encoding UL84 to the cotransfection mixture containing BAC-IN84/Ep resulted in the replication of oriLyt. Considering all these data, it is clear that UL84 is required for viral growth and that it provides an essential function that is required for lytic DNA replication. Recently, two laboratories generated HCMV UL84 BAC deletion mutants as part of an undertaking to identify essential and nonessential genes within the entire HCMV genome (9, 32). They reported that BAC recombinants with UL84 deletions failed to produce viral plaques, but no characterizations of gene expression patterns were performed. The data presented here confirm these results and extend the previous findings by presenting a detailed characterization of the effects on mRNA levels produced from specific HCMV genes in the absence of UL84 expression.

A real-time PCR analysis of viral transcripts showed that in cells transfected with BAC-IN84/Ep, all kinetic classes of viral transcripts were produced. An increase in late and early-late gene transcript accumulation at day 1 posttransfection was observed in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells compared to that in wt HCMV BAC-transfected cells. Surprisingly, late gene transcripts from the UL75 loci were observed even in the absence of viral DNA synthesis. UL75 as well as UL83 mRNA was observed as late as 10 days posttransfection. This correlated with the persistence of a low level of BAC-IN84/Ep DNA at this time as well as at times up to 21 days posttransfection. We also detected UL89 (7) mRNA by reverse transcription-PCR, again confirming that this early-late transcript was also produced in BAC-IN84/Ep-transfected cells (data not shown). For the early-late transcript encoded by UL83, the level of mRNA, as measured by real-time PCR, was 10-fold higher than that observed for wt HCMV BAC-transfected cells at day 1 postelectroporation. Interestingly, an increase in late and early-late gene expression was also reported for various IE2 deletion BAC mutants (29). These similar observations may signify that the lack of UL84 expression alters the activity of IE2, especially at the initial stages of viral gene expression, or that UL84 itself functions to inhibit late gene expression at early times in infection.

Previous results from transient transfection assays determined that UL84 was necessary for the formation of replication compartments in transfected cells (26). In addition, UL84 was shown to be a component of DNA replication compartments within transfected and infected cells (31). Here we showed that UL44 and IE2 failed to partition into replication compartments when they were expressed from BAC-IN84/Ep DNA in transfected cells. The lack of the formation of replication compartments in cells transfected with BAC-IN84/Ep suggests that UL84 may be implicated in the specific subcellular targeting of replication proteins to replication centers within the nucleus. The observation that replication compartments were not present in cells transfected with the mutant BAC can be interpreted several ways. We note that the lack of replication compartments may be due to the fact that viral DNA synthesis did not occur in cells transfected with the mutant and that therefore it would not be expected that these structures would form. However, it was demonstrated that the transient transfection of human herpesvirus 8 replication proteins in the absence of the human herpesvirus 8 oriLyt (and the absence of DNA synthesis) caused partitioning into replication compartments (30). This observation allows for the possibility that replication compartments can form in the absence of DNA synthesis. Nevertheless, the data presented here confirm that UL84 is a key factor for DNA synthesis and subsequent replication compartment formation in the context of the viral genome.

Our attempts to complement BAC-IN84/Ep viral growth by providing UL84 in trans failed. We used various UL84-expressing cell lines that were generated from retroviruses and a lentivirus as well as cotransfections of expression plasmids. In addition, cell lines were made from both human fibroblasts and U373 cells. Although we do not know the reason for the lack of complementation, we note that this phenomenon was observed with a recombinant BAC construct with an IE2 deletion (16). One possible explanation for the lack of transcomplementation is that the expression of UL84 is tightly regulated within the context of the virus and that the constitutive expression of episomal UL84 (for example, from a plasmid) is deleterious. Indeed, the overexpression of UL84 in U373 cells results in a transdominant inhibition of viral replication (10). Also, the data suggest that UL84 provides a regulatory function by interacting with IE2 in infected cells in addition to its DNA replication function. This interaction may regulate the timing of DNA synthesis and also suggests that the constitutive expression of UL84 may interfere with the activity of IE2.

We speculate that UL84 has two roles in the viral growth cycle. The first is a regulatory role, as it acts as a homodimer with IE2 to control the activity of IE2 with respect to the transactivation of viral promoters. Consistent with a possible regulatory function, it was found that UL84 is phosphorylated in vivo (K. Colletti and G. S. Pari, unpublished data). In addition, the interaction of UL84 with IE2 may serve to regulate the timing of DNA replication. The second activity concerns a direct interaction with oriLyt. This assumption is based on the data presented here coupled with earlier studies showing that transient oriLyt-dependent DNA replication failed to occur when this ORF was omitted from the transfection mixture (21, 26). In regard to a possible enzymatic function for UL84, we were able to find homology between UL84 amino acid motifs and other mammalian proteins that function in nucleic acid metabolism. One such homology search identified a close match to mammalian UTPase. Further studies are in progress to determine if UL84 is associated with any enzymatic activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Public Health Service grant AI45096.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbate, J., J. C. Lacayo, M. Prichard, G. Pari, and M. A. McVoy. 2001. Bifunctional protein conferring enhanced green fluorescence and puromycin resistance. BioTechniques 31:336-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn, J. H., E. J. Brignole III, and G. S. Hayward. 1998. Disruption of PML subnuclear domains by the acidic IE1 protein of human cytomegalovirus is mediated through interaction with PML and may modulate a RING finger-dependent cryptic transactivator function of PML. Mol. Cell. Biol 18:4899-4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahn, J. H., and G. S. Hayward. 1997. The major immediate-early proteins IE1 and IE2 of human cytomegalovirus colocalize with and disrupt PML-associated nuclear bodies at very early times in infected permissive cells. J. Virol. 71:4599-4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahn, J. H., W. J. Jang, and G. S. Hayward. 1999. The human cytomegalovirus IE2 and UL112-113 proteins accumulate in viral DNA replication compartments that initiate from the periphery of promyelocytic leukemia protein-associated nuclear bodies (PODs or ND10). J. Virol. 73:10458-10471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borst, E. M., G. Hahn, U. H. Koszinowski, and M. Messerle. 1999. Cloning of the human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome in Escherichia coli: a new approach for construction of HCMV mutants. J. Virol. 73:8320-8329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britt, W. J. 2000. Infectious clones of herpesviruses: a new approach for understanding viral gene function. Trends Microbiol. 8:262-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chee, M. S., A. T. Bankier, S. Beck, R. Bohni, C. M. Brown, R. Cerny, T. Horsnell, C. A. Hutchison III, T. Kouzarides, J. A. Martignetti, et al. 1990. Analysis of the protein-coding content of the sequence of human cytomegalovirus strain AD169. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 154:125-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Bruyn Kops, A., and D. M. Knipe. 1994. Preexisting nuclear architecture defines the intranuclear location of herpesvirus DNA replication structures. J. Virol. 68:3512-3526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunn, W., C. Chou, H. Li, R. Hai, D. Patterson, V. Stolc, H. Zhu, and F. Liu. 2003. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:14223-14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gebert, S., S. Schmolke, G. Sorg, S. Floss, B. Plachter, and T. Stamminger. 1997. The UL84 protein of human cytomegalovirus acts as a transdominant inhibitor of immediate-early-mediated transactivation that is able to prevent viral replication. J. Virol. 71:7048-7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He, Y. S., L. Xu, and E. S. Huang. 1992. Characterization of human cytomegalovirus UL84 early gene and identification of its putative protein product. J. Virol. 66:1098-1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ioannou, P. A., C. T. Amemiya, J. Garnes, P. M. Kroisel, H. Shizuya, C. Chen, M. A. Batzer, and P. J. de Jong. 1994. A new bacteriophage P1-derived vector for the propagation of large human DNA fragments. Nat. Genet. 6:84-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim, U. J., H. Shizuya, P. J. de Jong, B. Birren, and M. I. Simon. 1992. Stable propagation of cosmid sized human DNA inserts in an F factor based vector. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:1083-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liptak, L. M., S. L. Uprichard, and D. M. Knipe. 1996. Functional order of assembly of herpes simplex virus DNA replication proteins into prereplicative site structures. J. Virol. 70:1759-1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maniatis, T., E. Fritsch, and J. Sambrook. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 16.Marchini, A., H. Liu, and H. Zhu. 2001. Human cytomegalovirus with IE-2 (UL122) deleted fails to express early lytic genes. J. Virol. 75:1870-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McWatters, B. J., R. M. Stenberg, and J. A. Kerry. 2002. Characterization of the human cytomegalovirus UL75 (glycoprotein H) late gene promoter. Virology 303:309-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mocarski, E. J., and C. T. Courcelle. 2001. Cytomegaloviruses and their replication, p. 2629-2673. In D. M. Knipe et al. (ed.), Fields virology, 4th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 19.Pachl, C., W. S. Probert, K. M. Hermsen, F. R. Masiarz, L. Rasmussen, T. C. Merigan, and R. R. Spaete. 1989. The human cytomegalovirus strain Towne glycoprotein H gene encodes glycoprotein p86. Virology 169:418-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pande, H., S. W. Baak, A. D. Riggs, B. R. Clark, J. E. Shively, and J. A. Zaia. 1984. Cloning and physical mapping of a gene fragment coding for a 64-kilodalton major late antigen of human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 81:4965-4969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pari, G. S., and D. G. Anders. 1993. Eleven loci encoding trans-acting factors are required for transient complementation of human cytomegalovirus oriLyt-dependent DNA replication. J. Virol. 67:6979-6988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pari, G. S., M. A. Kacica, and D. G. Anders. 1993. Open reading frames UL44, IRS1/TRS1, and UL36-38 are required for transient complementation of human cytomegalovirus oriLyt-dependent DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 67:2575-2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prichard, M. N., N. Gao, S. Jairath, G. Mulamba, P. Krosky, D. M. Coen, B. O. Parker, and G. S. Pari. 1999. A recombinant human cytomegalovirus with a large deletion in UL97 has a severe replication deficiency. J. Virol. 73:5663-5670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reid, G. G., V. Ellsmore, and N. D. Stow. 2003. An analysis of the requirements for human cytomegalovirus oriLyt-dependent DNA synthesis in the presence of the herpes simplex virus type 1 replication fork proteins. Virology 308:303-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruger, B., S. Klages, B. Walla, J. Albrecht, B. Fleckenstein, P. Tomlinson, and B. Barrell. 1987. Primary structure and transcription of the genes coding for the two virion phosphoproteins pp65 and pp71 of human cytomegalovirus. J. Virol. 61:446-453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarisky, R. T., and G. S. Hayward. 1996. Evidence that the UL84 gene product of human cytomegalovirus is essential for promoting oriLyt-dependent DNA replication and formation of replication compartments in cotransfection assays. J. Virol. 70:7398-7413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shizuya, H., B. Birren, U. J. Kim, V. Mancino, T. Slepak, Y. Tachiiri, and M. Simon. 1992. Cloning and stable maintenance of 300-kilobase-pair fragments of human DNA in Escherichia coli using an F-factor-based vector. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:8794-8797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spector, D. J., and M. J. Tevethia. 1994. Protein-protein interactions between human cytomegalovirus IE2-580aa and pUL84 in lytically infected cells. J. Virol. 68:7549-7553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White, E. A., C. L. Clark, V. Sanchez, and D. H. Spector. 2004. Small internal deletions in the human cytomegalovirus IE2 gene result in nonviable recombinant viruses with differential defects in viral gene expression. J. Virol. 78:1817-1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu, F. Y., J. H. Ahn, D. J. Alcendor, W. J. Jang, J. Xiao, S. D. Hayward, and G. S. Hayward. 2001. Origin-independent assembly of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus DNA replication compartments in transient cotransfection assays and association with the ORF-K8 protein and cellular PML. J. Virol. 75:1487-1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xu, Y., K. S. Colletti, and G. S. Pari. 2002. Human cytomegalovirus UL84 localizes to the cell nucleus via a nuclear localization signal and is a component of viral replication compartments. J. Virol. 76:8931-8938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu, D., M. C. Silva, and T. Shenk. 2003. Functional map of human cytomegalovirus AD169 defined by global mutational analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:12396-12401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yurochko, A. D., E. S. Hwang, L. Rasmussen, S. Keay, L. Pereira, and E. S. Huang. 1997. The human cytomegalovirus UL55 (gB) and UL75 (gH) glycoprotein ligands initiate the rapid activation of Sp1 and NF-kappaB during infection. J. Virol. 71:5051-5059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]