Abstract

Background

Effective colorectal cancer screening depends on timely diagnostic evaluation in patients with abnormal fecal immunochemical tests (FIT). Although prior studies suggest low rates of follow-up colonoscopy, there is little information among patients in safety-net health systems and few data characterizing reasons for low follow-up rates.

Aims

Characterize factors contributing to lack of follow-up colonoscopy in a racially diverse and socioeconomically disadvantaged cohort of patients with abnormal FIT receiving care in an integrated safety-net health system.

Methods

We performed a retrospective electronic medical record review of patients aged 50-64 years with abnormal FIT at a population-based safety-net health system between January 2010 and July 2013. Review of electronic medical record focused on patients without follow-up colonoscopy to characterize patient-, provider-, and system-level reasons for lack of diagnostic evaluation. We used logistic regression analysis to identify predictors of follow-up colonoscopy within 12 months of abnormal FIT.

Results

Of 1267 patients with abnormal FIT, 536 (42.3%) failed to undergo follow-up colonoscopy within one year. Failure was attributable to patient-level factors in 307 (57%) cases, provider factors in 97 (18%) cases, system factors in 118 (22%) cases. In multivariate analysis, follow-up colonoscopy was less likely among those aged 61-64 years (OR 0.63, 95%CI 0.46–0.87) compared to 50-55 year-olds.

Conclusions

Nearly half (42%) of patients with abnormal FIT failed to undergo follow-up colonoscopy within one year. Lack of diagnostic evaluation is related to a combination of patient-, provider-, and system-level factors, highlighting the need for multi-level interventions to improve follow-up colonoscopy completion rates.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer screening, safety-net health system, fecal immunochemical test, colonoscopy, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer is the third leading cause of death in the United States.1 Colorectal cancer screening using colonoscopy or stool-based tests has been demonstrated to improve early tumor detection and reduce colorectal cancer-related mortality.2, 3 Stool-based screening tests, such as the fecal immunochemical test (FIT), are commonly used because they are noninvasive, inexpensive, readily available, and have higher completion rates than colonoscopy.4-6 Because of these advantages, FIT is the dominant colorectal cancer screening strategy employed by several commercial health maintenance organizations and the Veterans Affairs (VA) healthcare system.7, 8

However, the effectiveness of FIT-based colorectal cancer screening is dependent on patients with an abnormal result completing timely diagnostic evaluation.9 The process requires several steps and coordination between primary care providers, gastroenterologists, endoscopy schedulers, and patients for successful completion. Providers must accurately identify patients with abnormal FIT results, they must refer these patients for diagnostic colonoscopy, the healthcare system must facilitate test scheduling, and patients must comply with surveillance recommendations.10 Prior data have suggested more than one-fourth of patients in large integrated commercial health systems and more than half of patients in the VA with abnormal FIT fail to undergo diagnostic colonoscopy, largely related to lack of provider referrals for testing as well as patient non-adherence.11, 12

However, there are little published data in safety-net institutions, which care for racially diverse and socioeconomically disadvantaged patient populations who have the highest rates of colorectal cancer and lowest rates of colorectal cancer screening.13 Further, few studies have characterized patient-, provider-, and system-level reasons for lack of diagnostic evaluation in patients with abnormal FIT.14 From a patient perspective, suboptimal knowledge about the necessity of follow-up colonoscopy, negative health beliefs about colorectal cancer screening efficacy, and concerns about cost may cause patients to be unmotivated or unwilling to get follow-up colonoscopy.15 Primary care providers may be unlikely to order a colonoscopy if they perceive patients are unlikely to complete the test or may be overburdened with competing interests during clinic.15 At the system-level, safety-net systems may have more limited colonoscopy capacity and cumbersome colonoscopy referral processes.15-17 A better understanding of how factors at each of these levels contribute to low diagnostic evaluation rates is critical for developing future interventions to improve completion of the colorectal cancer screening process.

The primary aim of this study was to characterize patient-, provider-, and system-level reasons for lack of follow-up colonoscopy within one year of abnormal FIT among a racially diverse and socioeconomically disadvantaged cohort of patients engaged in primary care at a large, population-based integrated safety-net health system.

METHODS

Study Setting and Population

We performed a retrospective cohort study using electronic medical record review at Parkland Health & Hospital System (Parkland), the sole safety-net health system in Dallas County. Parkland is a publicly-funded integrated health system including a 900-bed hospital, 12 community-based primary care clinics, specialty clinics, and colonoscopy suites that is connected by a single comprehensive electronic medical record system. Poor, uninsured residents of Dallas are eligible for Parkland HEALTHplus, a county taxpayer financed medical assistance program which provides primary, secondary and tertiary care including colorectal cancer screening (via FIT or colonoscopy) and follow-up diagnostic colonoscopy for those with abnormal FIT results.

All patients were in the Parkland-University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) Population-Based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens (PROSPR) colorectal cancer (CRC) cohort, described in detail elsewhere.9 Briefly, PROSPR is a national consortium funded by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to support research characterizing the cancer screening process from initial screening to follow-up of abnormal tests to diagnosis and treatment.9 The Parkland-UTSW PROSPR CRC cohort includes Dallas county residents aged 50-64 years with at least 1 Parkland primary care visit on or after January 1, 2010.

Here, we selected the subset of PROSPR members who entered the cohort between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2012 and had an abnormal FIT during follow-up between January 1, 2010 and July 1, 2013. Exclusion criteria included: a) stool-based tests performed in-office or inpatient as these are not recommended for colorectal cancer screening, and b) patients with a history of colon cancer or colectomy. The study was approved by institutional review board at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Description of the Multi-Step Colorectal Cancer Screening Process in Safety Net Health System

Colorectal cancer screening in the Parkland Health System is available for all patients ≥50 years old, with choice of screening test at the discretion of the primary care provider; however, most Parkland patients undergo FIT testing. FIT is done with a 3-sample Beckman Coulter Hemoccult ICT test distributed during a clinic visit, and FIT results are sent to primary care providers’ electronic medical record results inbox. Patients with an abnormal FIT are typically informed of their test result by their clinic provider via telephone, letter, or at the time of their next clinic visit, during which primary care providers can place a colonoscopy referral via the electronic medical record. Then, a gastroenterology (GI) trained nurse reviews all colonoscopy referrals and determines if the patient: 1) meets criteria for conscious sedation, 2) meets criteria for general endotracheal anesthesia (GETA) requiring a pre-anesthesia evaluation, or 3) needs more information or additional testing (e.g., labs, cardiology clearance). If the latter, the nurse sends the referral back to the primary care provider for follow-up. After GI nurse approval, administrative staff mails a letter instructing patients to call and schedule a pre-procedural visit. During this visit, administrative staff provide colonoscopy prep instructions, collect a co-payment (amount determined by financial counselor), and schedule the colonoscopy. These visits were initiated to improve prep quality and decrease colonoscopy no-show rates. Given limited endoscopic capacity, colonoscopies are typically scheduled 6 – 8 weeks after the pre-procedure visit.

Data Collection

Patient demographics and clinical history were obtained from the electronic medical record. Data regarding FIT and colonoscopy completion were obtained by querying electronic medical record laboratory data for FIT testing and a combination of test orders and administrative claims data for colonoscopy. To characterize reasons for lack of diagnostic evaluation, two authors (J.M. and Z.M.) independently manually abstracted electronic medical records of patients who did not complete a colonoscopy within one year of an abnormal FIT. Both authors reviewed a 10% random sample as quality control, with a kappa of 0.92, and remaining charts were reviewed by one of the two authors. All cases with unknown or unclear reasons for lack of follow-up colonoscopy were discussed with co-authors (A.S., E.H., B.B., K.M., J.S.) to obtain consensus. Reasons were determined via review of orders, referrals and clinical notes in the electronic medical record and categorized into four categories based on the PROSPR trans-organ conceptual model of multi-level factors influencing steps in the colorectal cancer screening process.18 Based on review of the electronic medical record documentation, we determined whether lack of follow-up colonoscopy was due to: 1) patient, 2) provider, 3) system, or 4) unknown reasons.10 Patient reasons included refusal of colonoscopy or failure to show for appointments, etc; provider reasons included failure to place colonoscopy referral or did not respond to GI nurse request for more information or additional testing, etc; and system reasons were circumstances such as GI administrative staff did not mail letter or schedule pre-procedural appointment.

Statistical Analysis Plan

To characterize reasons for lack of follow-up testing after abnormal FIT, we first determined the proportion of patients who completed colonoscopy within 12 months of abnormal FIT. We used a one-year cut-off as colonoscopies more than 12 months after an abnormal FIT were unlikely related to the abnormal FIT result and this length of time was felt to be sufficient for colonoscopy scheduling, accounting for limited endoscopic capacity in a safety-net health system.26

We used univariate and multivariate logistic regression to identify predictors of colonoscopy completion within 12 months of abnormal FIT, with the multivariate logistic regression model including variables of a priori clinical importance (race/ethnicity, gender, comorbidity status, and receipt of GI subspecialty care), and factors with p<0.10 in univariate analysis. In exploratory secondary analyses, we used three multivariate logistic regression models to identify factors associated with failure to follow-up: patient vs. provider reasons, provider vs. system reasons, and patient vs. system reasons. Independent variables of interest included patient age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance status, Charlson comorbidity index, and receipt of any gastroenterology clinic visits in the year following FIT. We included receiving gastroenterology subspecialty care as a variable of interest because gastroenterologists have more connections in getting colonoscopies scheduled, may spend extra time counseling patients on the rationale for diagnostic colonoscopy, or such patients may be more motivated to have their GI problems addressed. Predictor variables with p<0.10 in univariate analysis and those of a priori significance (e.g. receipt of GI subspecialty care) were included in multivariate models to minimize type II error. Statistical significance was defined as p< 0.05 for multivariate analysis. All data analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of the 51,565 PROSPR CRC cohort members, 1,267 (2.5%) had an abnormal FIT test between January 2010 and July 2013. The median follow-up for the cohort after positive FIT was 10.0 (IQR 3.6 – 22.0) months. Colonoscopy was completed within 12 months in 731 (57.7%) patients, with colonoscopy completion rates of 31% at 3 months and 50% at 6 months. Characteristics of the 536 patients (42.3%) who had abnormal FIT tests but no follow-up colonoscopy are shown in Table 1. The median age of our cohort was 55 years, and 41.6% were male. Our patient population was racially diverse (42.4% Black, 36.0% Hispanic, and 16.0% Caucasian) and socioeconomically disadvantaged (65.3% uninsured and 17.6% Medicaid). Most patients (83.6%) were healthy with a Charlson comorbidity index ≤1. Although most (75%) patients continued to receive primary care in the year following their abnormal FIT result, only 2.3% were being followed in Gastroenterology clinic.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with Abnormal FIT in a Safety Health System

| Variable | All Patients (n=1267) | Patients with follow-up colonoscopy (n=731) | Patients without follow-up colonoscopy (n=536) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| 50-55 | 635 (50.1%) | 385 (52.7%) | 250 (46.6%) | 0.001 |

| 56-60 | 390 (30.8%) | 232 (31.7%) | 158 (29.5%) | |

| 61-64 | 242 (19.1%) | 114 (15.6%) | 128 (23.9%) | |

| Gender (% male) | 527 (41.6%) | 292 (39.9%) | 235 (43.8%) | 0.1643 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 203 (16.0%) | 112 (15.3%) | 91 (17.0%) | |

| Black | 537 (42.4%) | 301 (41.2%) | 236 (44.0%) | 0.4001 |

| Hispanic | 456 (36.0%) | 273 (37.3%) | 183 (34.1%) | |

| Other | 71 (5.6%) | 45 (6.2%) | 26 (4.9%) | |

| Insurance status* | ||||

| Uninsured (Charity)** | 822 (65.3%) | 496 (68.1%) | 326 (61.4%) | |

| Medicare | 160 (12.7%) | 75 (10.3%) | 85 (16.0%) | 0.0126 |

| Medicaid | 221 (17.6%) | 128 (17.6%) | 93 (17.5%) | |

| Private | 56 (4.4%) | 29 (4.0%) | 27 (5.1%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||

| 0 | 669 (52.8%) | 391 (53.5%) | 278 (51.9%) | 0.8291 |

| 1 | 390 (30.8%) | 223 (30.5%) | 167 (31.2%) | |

| 2+ | 208 (16.4%) | 117 (16.0%) | 91 (17.0%) | |

| Receipt of GI subspecialty care in year following FIT | 29 (2.3%) | 21 (2.9%) | 8 (1.5%) | 0.1046 |

Insurance was measured during cohort entry year. If multiple payors were present, the following trumping algorithm was used: Medicaid (dual eligible), Medicare, Commercial, Other, Uninsured (Charity), and Unknown.

Uninsured Dallas County residents can receive medical care using Parkland HEALTHplus, a county taxpayer financed insurance assistance program

Reasons for Lack of Follow-up Colonoscopy

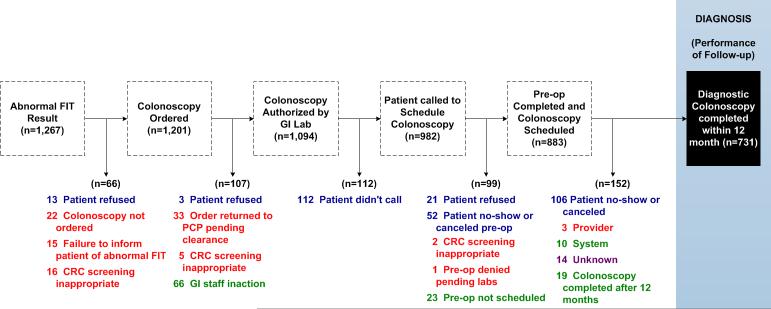

Figure 1 depicts the proportion of patients failing to complete each step in the colorectal cancer screening process. Overall, failure to complete diagnostic colonoscopy was attributable to patient-level factors in 307 (57%) cases, provider-level factors in 97 (18%) cases, system-level factors in 118 (22%) cases, and unknown reasons in 14 (3%) of cases. Although few cases (n=37) had documentation in the electronic medical record of a patient refusing follow-up colonoscopy, many patients (n=258) failed to show up for scheduled pre-op evaluation appointments or colonoscopy procedures. Provider factors included failure to inform the patient of the abnormal result, failure to order a colonoscopy, or failure to order any necessary pre-procedural evaluation. We observed 37 cases in which colonoscopy was not ordered and 37 cases in which the colonoscopy was ordered but the requisite pre-procedure labs and evaluation were not completed. An additional 23 patients had inappropriate FIT screening because they had a normal colonoscopy in the past 10 years. System factors included failure to process colonoscopy referrals (n=66), failure to schedule appointments or colonoscopy procedures (n=23), cancellation or delayed receipt (>12 months) of procedures due to lack of endoscopic capacity (n=29). Finally, we were unable assign reason for lack of colonoscopy for 14 patients.

Figure 1. Reasons for Failure to Obtain Diagnostic Colonoscopy after Abnormal FIT.

Failure to complete diagnostic colonoscopy was attributable to patient-level factors in 57% of cases (blue), provider-level factors in 18% of cases (red), system-level factors in 22% of cases (green), and unknown reasons in 3% of cases.

Predictors of Lack of Follow-up Colonoscopy

In univariate analysis, failure to complete diagnostic colonoscopy within 12 months of abnormal FIT was associated with older patient age and Medicare insurance status. Older patient age remained significant in multivariate analysis (Table 2), with higher rates of failure in patients aged 61-64 years compared to those aged 50-55 years (OR 1.59, 95%CI 1.15-2.17). Patients aged 61-64 years had colonoscopy completed in 48.0% of the time compared to 61.2% of those aged 50-55 years. Medicare insurance was also associated with higher rates of follow-up failure than patients without insurance (OR 1.49, 95%CI 1.02-2.13).

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Failure of Diagnostic Colonoscopy Completion among safety-net system patients with an abnormal FIT, n = 1226

| Variable | Multivariate Analysis Adjusted Odds Ratios (95% CIs) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 50 – 55 | Reference |

| 56 – 60 | 1.03 (0.79 – 1.33) |

| 61 – 64 | 1.59 (1.15 – 2.17) |

| Female gender | 0.87 (0.68 – 1.10) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | Reference |

| Black | 0.89 (0.64 – 1.25) |

| Hispanic | 0.80 (0.57 – 1.12) |

| Insurance status | |

| Uninsured | Reference |

| Medicare | 1.49 (1.02 – 2.13) |

| Medicaid | 1.19 (0.84 – 1.69) |

| Private | 1.61 (0.92 – 2.78) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | |

| 0 | Reference |

| 1 | 1.01 (0.78 – 1.32) |

| 2+ | 0.98 (0.69 – 1.37) |

| Receipt of GI subspecialty care in year following FIT | 0.52 (0.23 – 1.22) |

In exploratory subgroup analyses, we sought to identify factors associated with patient-, provider- and system-level failures. When we compared provider-level failures to patient- and system-level failures, Charlson comorbidity was significant in both multivariate models. Patients with a Charlson comorbidity index of ≥ 1 were more likely to have failure to follow-up colonoscopy attributed to provider reasons than patients without comorbidity (OR 1.75, 95%CI 1.06-2.88 for provider vs. patient and OR 1.97, 95%CI 1.10-3.51 for provider vs. system). No factors were significant in distinguishing between patient- and system-level failures.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based cohort of 1267 patients with an abnormal FIT cared for in a large, regional safety-net health system, we found that nearly half (42%) did not have follow-up colonoscopy within one year. Patient-related factors were the most common reason for failure, accounting for over one-half (57%) of cases with lack of follow-up colonoscopy; the most common patient failure was missing pre-op evaluation appointments or colonoscopy procedures. Provider-level and system-level reasons were also common, each accounting for 18% of follow-up failures.

Prior studies have shown over one-fourth of patients with abnormal FIT in large integrated commercial health systems fail to undergo follow-up colonoscopy.11, 12, 26 In our study we found a higher proportion of follow-up failures, with over one-third of patients in our safety-net health system failing to undergo follow-up colonoscopy after abnormal FIT. This difference is not surprising given similar racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities exist for colorectal cancer screening.19 Racial/ethnic minority and low-income, particularly uninsured, patients have increased barriers to medical care and thereby are at greatest risk for failing to undergo follow-up colonoscopy.16 We found consistently low rates of follow-up among patient subgroups, with older age and Medicare insurance being only the predictors of follow-up failure. However, over one-third of patients in all patient subgroups failed to complete follow-up colonoscopy.

We found failure to undergo follow-up colonoscopy was related to a combination of patient-, provider-, and system-level factors, which highlights the complexity of the diagnostic evaluation process. Despite all patients in our study being engaged in primary care, patient missed appointments remained the most common reason for lack of follow-up. Because we were limited to information in the electronic medical record notes, we were unable to identify the deeper underlying reasons for patient-level failures in our study. Prior studies suggest the presence of several barriers ranging from fears of discomfort, complications, or the bowel preparation to logistical concerns including difficulty with transportation, language barriers, difficulty with scheduling appointments, or financial concerns.20-22 Further, these barriers can be exacerbated by system-level factors such as multistep scheduling processes and/or requiring additional preoperative visits, which may exacerbate transportation and financial issues.10, 13, 14, 20 For example, it is possible the pre-procedure visit implemented at Parkland to increase patient visit adherence may have a paradoxical effect of increasing patient barriers and decreasing diagnostic colonoscopy completion rates. Qualitative studies, such as focus groups, can help better characterize patient- and provider-level barriers to colonoscopy completion in the future.

Patient- and system-level barriers can be particularly common in safety-net health systems, which care for large numbers of socioeconomically disadvantaged patients despite limited financial resources. Prior studies suggest provider-level failures can also be common among underinsured patients due to perceived lack of colonoscopy availability or financial disincentive15; however, this was not an issue in our study given Parkland's integrated structure and Parkland HEALTHplus coverage for follow-up diagnostic colonoscopy. Failure of diagnostic colonoscopy completion was most common among patients with Medicare or private insurance than those covered by Parkland HEALTHplus, the county charity plan, arguing against any impact of potential financial disincentives. Parkland employs salaried physicians from UT Southwestern Medical Center, thereby removing potential financial incentives for performing (or not performing) colonoscopy. Further, hospital staff members are responsible for all referral processing and scheduling, independent of the gastroenterologists. We found lack of follow-up colonoscopy was more likely to be due to provider-level failure among patients with higher comorbidity. This association is likely related to a lower benefit and higher risk of complications in this subgroup of patients. Lack of follow-up may be appropriate in some of these patients; however, discussions regarding risks and benefits should ideally be done prior to screening if providers or patients are unlikely to perform a diagnostic evaluation if the FIT is abnormal.

Prior studies have demonstrated patient-level (e.g. patient education workshops or transportation assistance), provider-level (e.g. electronic reminders), and system-level (e.g. reducing pre-procedural visits to streamline the diagnostic evaluation process) interventions can be effective at improving follow-up testing rates.23-25 However, many patients continue to not receive necessary diagnostic evaluation. Further, safety-net patients and health systems have increased barriers to colonoscopy completion compared to other practice settings, and these interventions may be even less effective in this setting.13 Therefore, interventions to improve colonoscopy completion rates will likely need to be multi-level, focusing on reducing barriers at each of these levels, to be highly effective.14

Our study had limitations that must be taken into consideration when interpreting study results. The study was conducted in a single safety-net health system among poor, socially disadvantaged patients, aged < 65 years, so our results may not be generalized to other health systems. Further, our system does not have open access endoscopy whereas this is available in some centers. However, we believe this racially diverse socioeconomically disadvantaged cohort of patients is an important population to study because of the marked disparities in colorectal cancer screening and mortality. Because this was an electronic medical record chart review study, we cannot comment on the impact of things not documented in the medical record. For example, patient-provider discussions about follow-up of FIT+ results and/or reasons for no follow-up (such as limited life expectation or patient refusal) may not be recorded in all cases. Similarly, we were unable to determine precise reasons for some system-level failures including lack of referral processing or scheduling. However, we believe missing data on completion of follow-up colonoscopy is very unlikely because most patients would have very high out-of-pocket costs to have a diagnostic colonoscopy outside of Parkland, which is the sole safety net provider in the county. Outside providers are very unlikely to provide non-emergent colonoscopy for uninsured patients or those with Medicaid. Finally, our multivariate analyses were limited by small sample size, particularly for subgroup analyses, and limited number of potential covariates.

In summary, nearly one half (42%) of patients with an abnormal FIT test in a safety-net health system failed to undergo follow-up colonoscopy within one year. Patient factors explained over half (57%) of the failures, but provider- and system-level barriers are also common with each accounted for 18-22% of follow-up failures. Future quality improvement and intervention studies will need to target key steps in the colorectal cancer screening process, such as follow-up of abnormal FIT results, where breakdowns are most common and often explained by a combination of patient-, provider-, and system-level factors.

Highlights.

◆ 42% of patients with abnormal FIT fail to have follow-up colonoscopy within one year

◆ Lack of follow-up is due to combination of patient, provider, and system-level factors

◆ Multi-level interventions are needed to improve timely follow-up of abnormal FITs

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was conducted as part of the NCI-funded consortium Population-Based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regiments (PROSPR) with support from NIH/NCI Grant U54CA163308-01. Dr. Halm was supported in part by the AHRQ Center for Patient-Centered Outcomes Research (R24 HS022418). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or AHRQ.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions: All authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data and/or analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, Dash C, Giardiello FM, Glick S, Johnson D, Johnson CD, Levin TR, Pickhardt PJ, Rex DK, Smith RA, Thorson A, Winawer SJ. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elmunzer BJ, Singal AG, Sussman JB, Deshpande AR, Sussman DA, Conte ML, Dwamena BA, Rogers MA, Schoenfeld PS, Inadomi JM, Saini SD, Waljee AK. Comparing the effectiveness of competing tests for reducing colorectal cancer mortality: a network meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:700–709. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeBourcy AC, Lichtenberger S, Felton S, Butterfield KT, Ahnen DJ, Denberg TD. Community-based preferences for stool cards versus colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:169–74. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0480-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, James PD, Mangham CM. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1472–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03386-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jorgensen OD, Sondergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348:1467–71. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03430-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Serag HB, Petersen L, Hampel H, Richardson P, Cooper G. The use of screening colonoscopy for patients cared for by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2202–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.20.2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moiel D, Thompson J. Early detection of colon cancer-the kaiser permanente northwest 30-year history: how do we measure success? Is it the test, the number of tests, the stage, or the percentage of screen-detected patients? Perm J. 2011;15:30–8. doi: 10.7812/tpp/11-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiro JA, Kamineni A, Levin TR, Zheng Y, Schottinger JS, Rutter CM, Corley DA, Skinner CS, Chubak J, Doubeni CA, Halm EA, Gupta S, Wernli KJ, Klabunde C. The colorectal cancer screening process in community settings: a conceptual model for the population-based research optimizing screening through personalized regimens consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1147–58. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zapka J, Taplin SH, Price RA, Cranos C, Yabroff R. Factors in quality care--the case of follow-up to abnormal cancer screening tests--problems in the steps and interfaces of care. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:58–71. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlson CM, Kirby KA, Casadei MA, Partin MR, Kistler CE, Walter LC. Lack of follow-up after fecal occult blood testing in older adults: inappropriate screening or failure to follow up? Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:249–56. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher DA, Jeffreys A, Coffman CJ, Fasanella K. Barriers to full colon evaluation for a positive fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1232–5. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, Sussman DA, Doubeni CA, Anderson DS, Day L, Deshpande AR, Elmunzer BJ, Laiyemo AO, Mendez J, Somsouk M, Allison J, Bhuket T, Geng Z, Green BB, Itzkowitz SH, Martinez ME. Challenges and possible solutions to colorectal cancer screening for the underserved. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju032. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zapka JM, Edwards HM, Chollette V, Taplin SH. Follow-up to abnormal cancer screening tests: considering the multilevel context of care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1965–73. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Malley AS, Beaton E, Yabroff KR, Abramson R, Mandelblatt J. Patient and provider barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the primary care safety-net. Prev Med. 2004;39:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Green AR, Peters-Lewis A, Percac-Lima S, Betancourt JR, Richter JM, Janairo MP, Gamba GB, Atlas SJ. Barriers to screening colonoscopy for low-income Latino and white patients in an urban community health center. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:834–40. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0572-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ward E, Halpern M, Schrag N, Cokkinides V, DeSantis C, Bandi P, Siegel R, Stewart A, Jemal A. Association of insurance with cancer care utilization and outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:9–31. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaber EF, Kim JJ, Schapira MM, Tosteson AN, Zauber AG, Geiger AM, Kamineni A, Weaver DL, Tiro J. Unifying Screening Processes Within the PROSPR Consortium: A Conceptual Model for Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancer Screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv120. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goebel M, Singal AG, Nodora J, Castaneda S, Martinez E, Doubeni C, Laiyemo A, Gupta S. How can we boost colorectal and hepatocellular carcinoma screening among underserved populations? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;17:22. doi: 10.1007/s11894-015-0445-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S, Tong L, Allison JE, Carter E, Koch M, Rockey DC, Anderson P, Ahn C, Argenbright K, Skinner CS. Screening for colorectal cancer in a safety-net health care system: access to care is critical and has implications for screening policy. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2373–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones RM, Devers KJ, Kuzel AJ, Woolf SH. Patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening: a mixed-methods analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:508–16. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones RM, Woolf SH, Cunningham TD, Johnson RE, Krist AH, Rothemich SF, Vernon SW. The relative importance of patient-reported barriers to colorectal cancer screening. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bastani R, Yabroff KR, Myers RE, Glenn B. Interventions to improve follow-up of abnormal findings in cancer screening. Cancer. 2004;101:1188–200. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yabroff KR, Washington KS, Leader A, Neilson E, Mandelblatt J. Is the promise of cancer-screening programs being compromised? Quality of follow-up care after abnormal screening results. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60:294–331. doi: 10.1177/1077558703254698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yabroff KR, Kerner JF, Mandelblatt JS. Effectiveness of interventions to improve follow-up after abnormal cervical cancer screening. Prev Med. 2000;31:429–39. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chubak J, Garcia M, Burnett-Hartman A, Zheng Y, et al. Time to colonoscopy after positive fecal blood test in four US healthcare systems. Cancer Epi Biomarkers Prev. 2016 doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]