Abstract

Angiotensin-II (Ang-II) is a well-established mediator of vascular remodeling. The multifunctional calcium-calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CaMKII) is activated by Ang-II and regulates Erk1/2 and Akt-dependent signaling in cultured smooth muscle cells in vitro. Its role in Ang-II-dependent vascular remodeling in vivo is far less defined. Using a model of transgenic CaMKII inhibition selectively in smooth muscle cells, we found that CaMKII inhibition exaggerated remodeling after chronic Ang-II treatment and agonist-dependent vasoconstriction in second-order mesenteric arteries. These findings were associated with increased mRNA and protein expression of smooth muscle structural proteins. As a potential mechanism, CaMKII reduced serum response factor-dependent transcriptional activity. In summary, our findings identify CaMKII as an important regulator of smooth muscle function in Ang-II hypertension in vivo.

Keywords: CaMKII, Ang-II, remodeling, smooth muscle

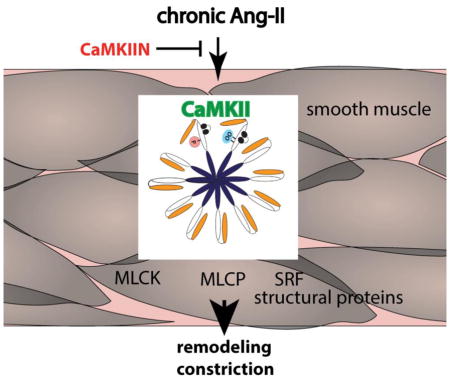

Graphical abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Chronic hypertension alters the structure and mechanics of small arteries. Remodeling of the vascular structure during hypertension is promoted by numerous factors, including blood pressure and flow, circulating neurohormones and growth factors [1]. In most small arteries, hypertension induces inward remodeling, defined as a reduction in external diameter [2, 3]. However, in some vascular beds such as second- and third-order mesenteric arteries, hypertrophy of the vessel wall can occur [4, 5]. These data are of clinical relevance since increased hypertrophic remodeling of small arteries is directly correlated with adverse cardiovascular events in patients with hypertension [6]. Angiotensin-II (Ang-II) infusion is one of the most commonly studied animal models of hypertension. This model is of translational significance because numerous studies have demonstrated that administration of Ang-II inhibitors protects from small vessel remodeling in models of hypertension in rodents and in hypertensive humans [7–10].

The multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) is a ubiquitously expressed Ca2+-dependent kinase that has been shown to promote Ca2+ handling, ion channel function, and Ca2+-dependent transcription in contractile tissue [11]. Ang-II acutely activates CaMKII in cultured smooth muscle cells [12–16], triggering pro-growth signaling pathways by activation of MAP kinase-dependent signaling [14, 17, 18]. The role of CaMKII in intact blood vessels has only emerged in the last years with the advent of genetic models [19–21]. We recently developed an in vivo model of transgenic CaMKII inhibition selectively in VSMC using the potent CaMKII inhibitor peptide, CaMKIIN. In this model, under baseline conditions, CaMKII inhibition in VSMC decreases intracellular and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ levels without significantly affecting vasoconstriction or vascular structure [22]. However, after chronic Ang-II infusion, CaMKII inhibition reduces blood pressure, prevents of aortic stiffening and blunts splanchnic and renal nerve activity [23].

Previous studies on vascular remodeling in hypertension have led to the classic concept that repeated episodes of blood pressure elevation elicit small artery remodeling that enhances vasoconstriction and sustains hypertension [24]. Thus, remodeling, vasoconstriction and blood pressure are expected to develop in concert and promote each other. However, data have emerged that do not align with this concept [25]. In our previous work, we assessed aortic vasoconstriction in hypertensive mice and unexpectedly detected no decrease in constriction with CaMKII inhibition [23]. Since the vascular tone of mesenteric arteries is important for blood pressure increases under chronic Ang-II infusion [26], these previous findings prompted us to investigate how CaMKII inhibition selectively in VSMC affects remodeling of mesenteric arteries following Ang-II infusion in vivo.

2. METHODS

2.1. Antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: anti-β-actin (Cell Signaling, 4970), anti-SM-α-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, SC-1616), anti-caldesmon (Cell Signaling, #12503), anti-calponin (Santa Cruz, SC-16604) anti-tropomyosin (Santa Cruz, SC-28543), anti-myosin heavy chain 9 (Cell Signaling, 3403), anti-CaMKII (LifeSpan Biosciences, LS-B3743 for immunofluorescence or EMD-Millipore 07–1496 for immunoblots), anti-pThr 287 CaMKII (Cell Signaling, 12716), anti-myosin heavy chain 11 (Milipore, MABT464), anti-cyclin E (Santa Cruz, SC-481) and anti-PCNA (Abcam, ab29), anti-p-Thr 696 MYPT (MLCP) (Santa Cruz, sc-17556-R), anti-MYPT (Santa Cruz, sc-25618), anti-p-MLCK Ser1760 (Invitrogen/Thermofisher, 44–1085G), anti-MLCK (Abcam, ab76092), anti-p-MLC20 Thr18/Ser19 and anti-MLC20 (Cell Signaling, 3674 and 8505). The ox-CaMKII antibody was a generous gift from Dr. Mark E. Anderson, Johns Hopkins University).

2.2. Mice

All experimental procedures were approved by the University of Iowa and the Iowa City VA Health Care System Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All procedures were in compliance with the standards for the care and use of laboratory animals of the Institute of Laboratory Animal Resource, National Academy of Science. TG HA-CaMKIIN mice were generated as previously described [22] and backcrossed with C57Bl/6 mice and mated with mice carrying a Cre recombinase gene controlled by the SM22α promoter to generate TG SM-CaMKIIN mice (Jackson Laboratory, 004746) [27]. Littermates that did not carry the HA-CaMKIIN transgene served as wild-type (WT) controls. Experiments were performed on mice between 10–12 weeks of age in male and female mice in equal proportions.

2.3. Osmotic Mini-Pumps

Chronic subcutaneous infusion of Ang-II (1.25 μg/kg/min, Anaspec) was performed using Alzet osmotic mini-pumps (model 1002, DURECT Corporation) as we previously reported [23].

2.4. Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Second-order mesenteric arteries of TgSM HA-CaMKIIN and WT mice were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde embedded in paraffin. 10μm sections were either stained with H&E. For immunostaining, the sections were subjected to heat-mediated antigen retrieval using 0.01 M citrate buffer and permeabilized in 1% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Sections were washed in PBS and then non-specific binding was blocked using a M.O.M. kit (Vector Labs) for 1 hr followed by incubation in anti-α-smooth muscle actin antibody (1:200) for 30 min at room temperature. After washing in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, sections were preincubated in 5% goat serum for 30 min and then incubated with anti-CaMKII (LifeSpan Biosciences,1:100) overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies were detected with AlexaFluor 488- or 568-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). Sections were counterstained with TO-PRO-3 (Invitrogen/ThermoFisher) to visualize nuclei.

2.5. CaMKII Kinase Activity Assay

Fresh lysates of TgSM HA-CaMKIIN and WT mesenteric arteries were lysed in 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1mM EGTA, 1mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM benzamidine, 20 mg/l soybean trypsin inhibitor, 5 mg/l leupeptin; 1 μM microcystin LR, 20 mM Na2H2P2O7,; 50 mM NaF; 50 mM β-glycerophosphate disodium. 10 μg protein were incubated in the presence of the synthetic substrate 20 μM Syntide (Sigma) in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1 mM DTT and 0.4 mM [γ-32P] ATP to determine autonomous Ca2+/CaM-independent activity. To measure Ca2+/CaM-activated (total) activity, 0.5 mM CaCl2 and 1 μM calmodulin were added instead of EGTA. Total and autonomous activity was determined as described previously [22, 28]. The assay mix was incubated minutes at 30° C; spotted onto Whatman P81 paper; washed in water, rinsed in ethanol, dried and counted in Bio-Safe II scintillation counting cocktail (RPI). The Ca2+/CaM-activated (total) activity is indicative of total levels of CaMKII in a sample, whereas the autonomous Ca2+/CaM-independent activity reflects the amount of active CaMKII.

2.6. Mesenteric Vessel Remodeling

Second order mesenteric arteries were dissected and placed in Krebs buffer. Arteries were transferred to a pressurized myograph system (DMT) and equilibrated for 30 min at 75 mmHg under no-flow conditions. The passive diameter was determined in Ca2+-free Krebs buffer containing SNP (10−5 M) and EGTA (2 mM). The vessel diameters under passive conditions at a pressure of 75 mmHg were utilized for structural analysis (wall thickness, % media/lumen ratio) calculated as described [7]. The circumferential wall stress was calculated according to: wall stress= mean blood pressure X lumen diameter / 2 / wall thickness. The data are expressed in kPa according to the following conversion: 1mm Hg equals 1333 dyne/cm2, and 1 dyne/cm2 equals 0.1 Pa [29].

2.7. Vascular reactivity studies

Vascular responses in second-order mesenteric arteries were measured using videomicroscopy using previously published methods [30]. The endothelium was removed and vessel viability determined by measurement of responses to KCl (50 mM). Concentration response curves to Ang-II (10−9 to 10−5 M), phenylephrine (10−8 – 10−6 M) and KCl (25 to 100 mM) were performed.

2.8. Immunoblotting

Aliquots of whole tissue lysate (25μg) from mesenteric arteries were resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. After blocking with 5% BSA, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Biorad). The proteins were visualized with the ECL chemiluminescence (Amersham). Densitometry was performed using NIH Image J software.

2.9. Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNA extraction kit and cDNA transcribed as previously reported with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Thermofisher) [22]. Message expression was quantified using an iQ Lightcycler (Bio-Rad) with SYBR green dye and normalized to acidic ribosomal phosphoprotein (ARP) mRNA. Specificity and replication efficiency were tested for each primer pair (Table 1). All primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies.

Table 1.

qrtPCR primers

| MYH11 | forward | 5′-ACT ATG CTG GGA AGG TGG AC |

| MYH11 | reverse | 5′-CAA ACT TGT CAG AGG AGG CA |

| tropomyosin | forward | 5′-CCC TGG TTG AAA GGT ATG CT |

| tropomyosin | reverse | 5′-CAT CTC ATG CAC TCC TTG CT |

| caldesmon | forward | 5′-GGG AGG AGG AAG AGA AGA GG |

| caldesmon | reverse | 5- CGA GCC TTT AGG AGT GAA GC |

| calponin | forward | 5′-CCG GAG AAG TTG AGA GAA GG |

| calponin | reverse | 5′-CTG CTG ACT GGC AAA CTT GT |

| myocardin | forward | 5′-GAT GCA GTG AAG CAG CAA AT |

| myocardin | reverse | 5′-CTG CTG ACT GGC AAA CTT GT |

| CaMKIIγ | forward | 5′-TTG AAC AAG AAG TCG GAT GG-3′ |

| CaMKIIγ | reverse | 5′-GCT GGG CTT ACG AGA CTG TT-3′ |

| CaMKIIδ | forward | 5′-GCT AGA CGG AAA CTG AAG GG-3′ |

| CaMKIIδ | reverse | 5′-CCT CAA TGG TGG TGT TTG AG-3′ |

| ARP | forward | 5′-CAT CCA GCA GGT GTT TGA CAA-3′ |

| ARP | reverse | 5′-ATT GCG GAC ACC CTC TAG GAA G-3′ |

2.10. Serum Response Factor Promoter Assays

293T cells were transfected at 30% confluence with SM22α-Luc (containing a 1434 bp promoter sequence in pBasic-Luc), myocardin expression vector (containing residues 1–801, in pcDNA3.1+), both kind gifts of Dr. Eric Olsen, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) [31], TK renilla and CaMKII T287D (constitutively active) or CaMKII K42M (kinase dead, in pCMV) with X-tremeGENE 9 DNA Transfection Reagent (Roche) at a ratio of 25:5:1:5. The CaMKII constructs were a kind gift from Dr. Mark E. Anderson, Johns Hopkins University. After transfection for 24 h, the luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

2.11. Statistics

Values are expressed as mean±SEM and compared within groups using Student’s t-test or ANOVA followed by appropriate post-hoc analysis. GraphPad Prism 7.0 software was used for the statistical analysis. A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. CaMKII is activated in mesenteric arteries by chronic Ang-II infusion

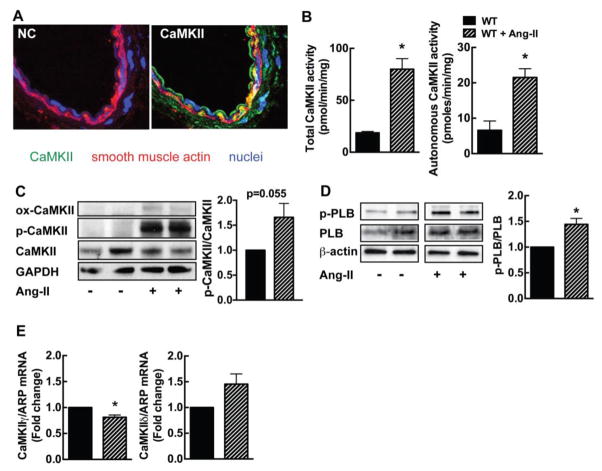

First, we ascertained that CaMKII protein is robustly expressed in the medial layer of mesenteric arteries (Figure 1A). After Ang-II infusion at pressor dose for 14 days, we detected an increase in autonomous and total CaMKII activity (Figure 1B). These data demonstrate that CaMKII is expressed in the media of mesenteric arteries and activated by Ang-II infusion. Moreover, we performed immunoblots for activated phosphorylated and oxidized CaMKII and detected a increase in active forms of CaMKII after Ang-II infusion (Figure 1C). As additional readout of CaMKII activity, we probed for phospholamban that is phosphorylated at Thr17. This phosphorylation site is deemed to be phosphorylated by CaMKII [32]. Phosphorylation at Thr17 was increased in mesenteric arteries after Ang-II infusion (Figure 1D). Since Ang-II infusion may affect CaMKII expression, we determined CaMKII isoform expression by qrtPCR. Chronic Ang-II infusion significantly decreased the mRNA expression of the CaMKIIγ isoform; no significant increase in CaMKIIδ mRNA was seen (Figure 1E).

Figure 1. CaMKII is activated in mesenteric arteries by chronic Ang-II infusion.

(A) Immunofluorescence for CaMKII (green; smooth muscle actin, red; TO-PRO-III (nuclei), blue). NC, negative control without primary antibody (40X). (B) CaMKII activity assay in mesenteric arteries of WT mice at baseline and on day 14 of Ang-II infusion. Total activity is a measure of total CaMKII protein in the sample. Autonomous activity reflects active CaMKII. (C) Representative immunoblots for active phosphorylated (p-CaMKII) and oxidized (ox-CaMKII) CaMKII and summary data in mesenteric arteries of WT mice at baseline and on day 14 of Ang-II infusion. (D) Representative immunoblots and summary data for active phosphorylated phospholamban Th7-17 (PLB). (E) Expression of CaMKII γ and δ isoforms by qRT-PCR in mesenteric arteries of WT mice at baseline and on day 14 of Ang-II infusion. For B and E, n=3–5 independent experiments; * p<0.05 compared to WT by unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

3.2. CaMKII inhibition promotes vasoconstriction and remodeling after chronic Ang-II infusion

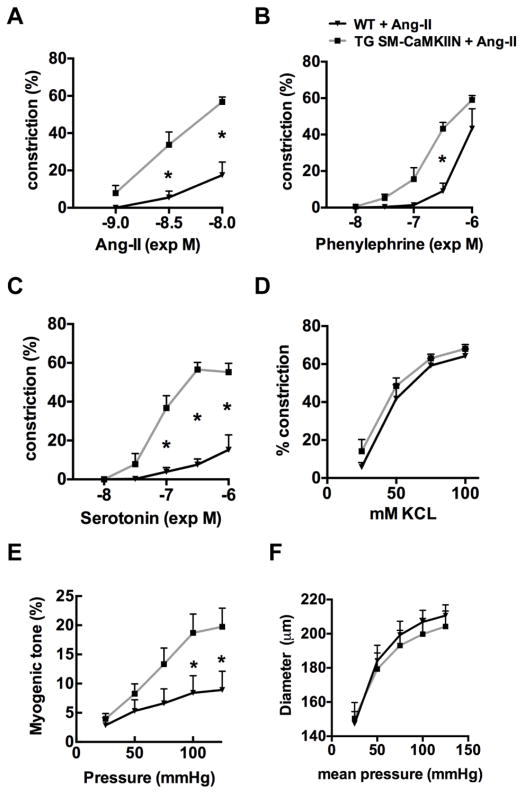

Next, we tested the response of isolated blood vessels after 14 days of Ang-II infusion to increasing concentrations of Ang-II, phenylephrine, serotonin, or KCl. We detected significantly enhanced vasoconstriction in TG SM-CaMKIIN mesenteric arteries in response to serotonin, phenylephrine and Ang-II as compared to WT arteries (Figure 2A–C). Constriction to KCl was similar between genotypes (Figure 2D). The myogenic tone was increased in mice with CaMKIIN inhibition (Figure 2E). However, no differences in the external mesenteric artery wall diameter were detected under Ca2+-free conditions (Figure 2F). We also determined intracellular Ca2+ levels ([Ca2+]i) in VSMC from mesenteric arteries after Ang-II infusion for 14 days. In accordance with previous findings in studies without Ang-II infusion [22], [Ca2+]i was decreased in samples from TG SM-CaMKIIN mice (data not shown).

Figure 2. CaMKII inhibition enhances vasoconstriction in mesenteric arteries after Ang-II infusion.

Vasoconstriction of endothelium-denuded second-order mesenteric arteries to (A) Ang-II, (B) phenylephrine (PE), (C) serotonin (5-HT), (D) KCl. (E) Myogenic tone. (F) External diameter under Ca2+-free conditions, n=5–8 mice per group. * p<0.05 compared to WT by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons tests.

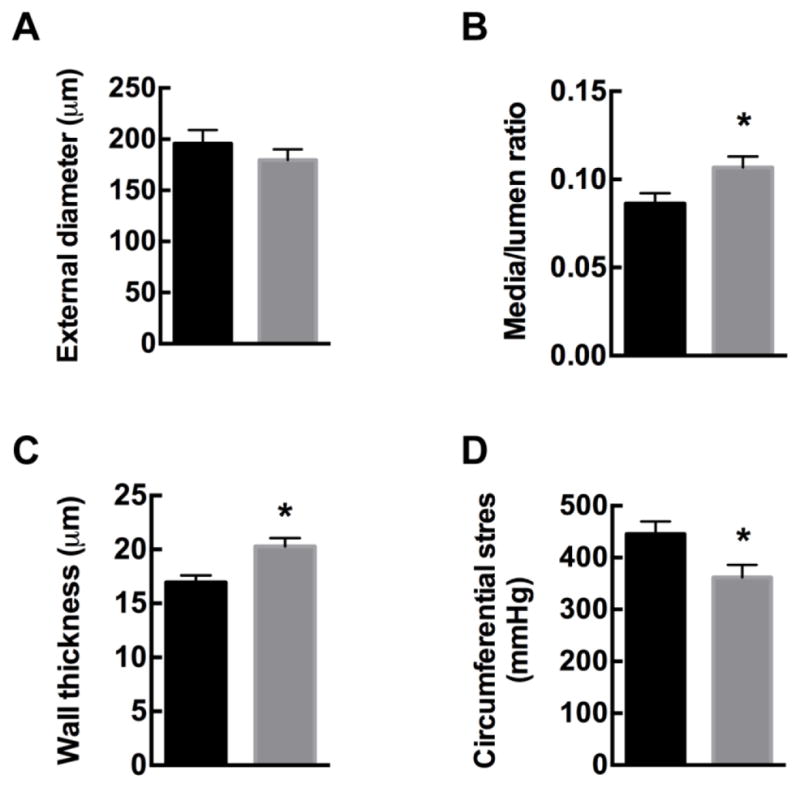

Moreover, we assessed the effect of CaMKII inhibition in VSMC on remodeling of second-order mesenteric arteries after Ang-II administration. We previously reported that baseline vascular structure is similar in WT and TG SM-CaMKIIN mice [22]. After 14 days of Ang-II infusion in TG SM-CaMKIIN and WT littermates, we determined internal and external vessel diameters in pressurized mesenteric arteries at 75 mmHg under Ca2+-free conditions. In WT mesenteric arteries, as expected, chronic Ang-II infusion led to eutrophic inward remodeling compared to untreated vessels (data not shown). Chronic Ang-II treatment resulted in a significantly greater hypertrophic remodeling defined by increased media/lumen ratio and wall thickness in TG SM-CaMKIIN samples compared to WT (Figure 3A–C). As derived from these measurements, the circumferential stress was lower under CaMKIIN inhibition (Figure 3D). These findings demonstrate that CaMKII inhibition in VSMC promotes mesenteric artery remodeling under Ang-II infusion.

Figure 3. CaMKII inhibition enhances Ang-II-induced inward remodeling in mesenteric arteries.

WT and TG SM-CaMKIIN mice were infused with Ang-II for 14 days, and mesenteric arteries isolated. Wall diameters of Ang-II-treated mesenteric arteries were assessed under passive conditions at a pressure of 75 mmHg. (A) External wall diameter, (B) media/lumen ratio, (C) wall thickness, and (D) circumferential stress. n=8–9 mesenteric arteries per group. * p<0.05 compared to WT by unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

3.3. CaMKII inhibition does not alter myosin light chain phosphorylation

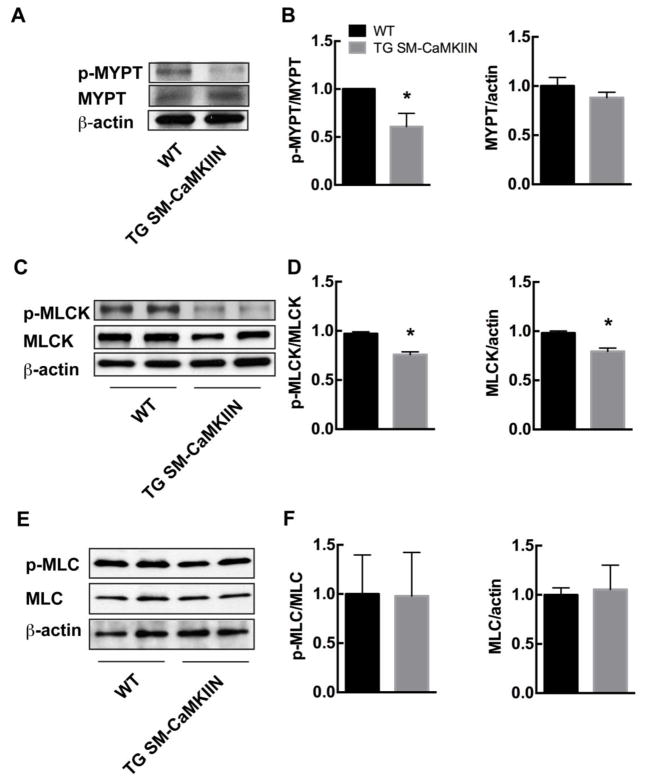

A major determinant of VSMC contraction is the phosphorylation state of myosin light chain (MLC), which is regulated through the opposing effects of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) and phosphatase (MLCP). Despite diminished agonist-induced [Ca2+]i in TG SM-CaMKIIN VSMC, the agonist-induced vasoconstriction was increased, suggesting greater MLC phosphorylation either through decreased MLCP activity or increased MLCK activity under CaMKII inhibition. Therefore, we evaluated phosphorylation of the MLCP regulatory subunit MYPT, MLCK, and MLC in mesenteric arteries isolated from WT or TG SM-CaMKIIN mice after chronic Ang-II infusion. First, we detected significantly lower levels of phosphorylation of MYPT Thr696 in TG SM-CaMKIIN (Figure 4A, B). Rho kinase protein expression that controls MYPT phosphorylation was not affected by CaMKII inhibition (data not shown). Next, we assessed the activation status of MLCK. CaMKII phosphorylation of MLCK abrogates Ca2+/CaM binding to MLCK and thereby lowers activity [33–35]. CaMKII inhibition decreased MLCK phosphorylation and total protein levels (Figure 4C, D). Consistent with the activation of the two opposing regulatory pathways, phosphorylation of myosin light chain 20 (MLC20), the downstream target of MLCK and MLCP, was not different between genotypes (Figure 4E, F). These data provide evidence that CaMKII inhibition under chronic Ang-II signaling increases MLCP and MLCK activity. Both mechanisms counteract each other, thus leading to no difference in MLC phosphorylation between genotypes. Thus, the alteration of MLCP and MLCK activity under CaMKII inhibition are unlikely to account for the enhanced vasoconstriction or myogenic tone.

Figure 4. CaMKII inhibition decreases ROCK activity and MLCK phosphorylation, consistent with increased MLCP and MLCK activity.

(A, B) Representative immunoblots (A) and summary data (B) for p-MYPT and total MYPT (n=4 independent experiments). (C, D) Representative immunoblots (C) and summary data (D) for p-MLCK and total MLCK (n=4 independent experiments). (E, F) Representative immunoblots (E) and summary data (F) for p-MLC20 and total MLC20 (n=5 independent experiments). In all immunoblots, mesenteric arteries of 5–7 Ang-II-treated mice were pooled for one sample. Loading control β-actin. * p<0.05 compared to WT by unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

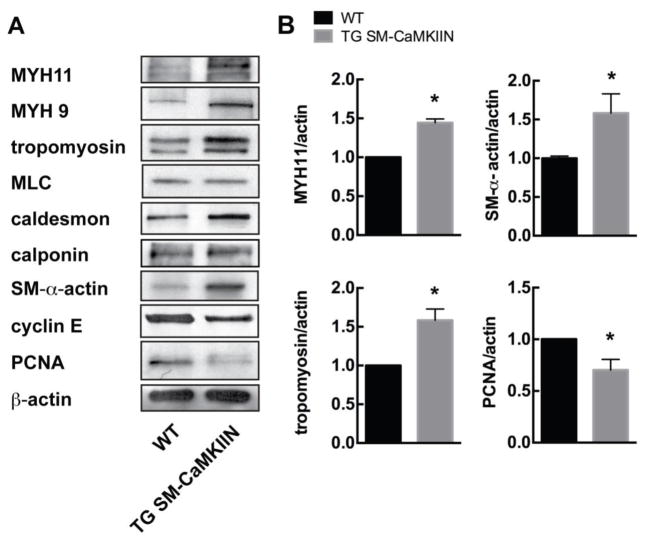

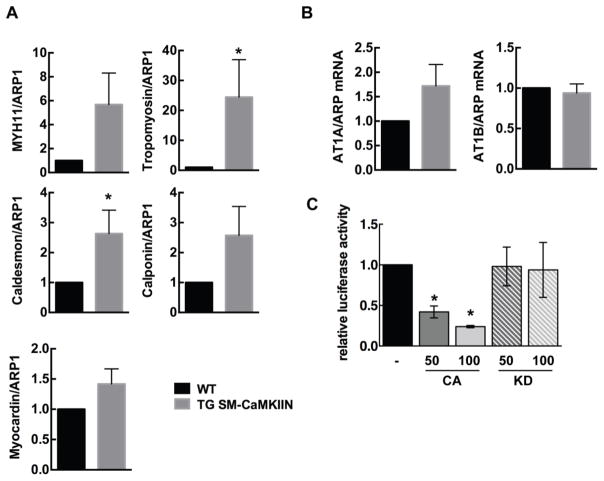

3.4. CaMKII inhibition promotes the structural protein expression in chronic Ang-II stimulation

Next, we examined protein levels of genes classically associated with hypertrophy and VSMC contraction. In mesenteric arteries isolated from TG SM-CaMKIIN and WT mice after chronic Ang-II infusion, we found that expression of MYH11, MYH9, tropomyosin, SM-α-actin and caldesmon was increased under CaMKII inhibition (Figure 5A, B). In contrast, TG SM-CaMKIIN mesenteric arteries had decreased expression of the proliferative gene PCNA and cyclin E as compared to WT VSMC. These data suggest that CaMKII inhibition promotes structural remodeling via enhanced expression of smooth muscle structural proteins.

Figure 5. CaMKII inhibition under Ang-II treatment increases expression of structural proteins.

(A) Representative immunoblots for structural proteins myosin heavy chain 11 (MYH11), myosin heavy chain 9 (MYH9), tropomyosin, myosin light chain (MLC), caldesmon, calponin, smooth muscle (SM) α-actin, cyclin E and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). β-actin, loading control. Mesenteric arteries of 5–7 Ang-II-treated mice were pooled per lane. (B) Summary data for three independent experiments normalized to β-actin. *p<0.05 compared to WT by unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

In accordance with the data on protein expression, mRNA levels for tropomyosin and caldesmon were significantly increased in mesenteric arteries from TG SM-CaMKIIN mice after Ang-II infusion (Figure 6A). Similar trends were seen for myocardin, MYH11 and calponin. We next examined whether CaMKII inhibition increases the expression of Ang-II receptors and thereby promotes remodeling. In particular, the Ang-II receptor 1B has been postulated to mediate the hypertrophic effect of Ang-II on the arterial wall [36]. However, no significant difference in mRNA levels of Ang-II receptor 1A or B were detected (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. CaMKII regulates SRF-dependent promoter activity.

(A) qrtPCR for MYH11, MYH9, tropomyosin, myocardin and caldesmon. (B) qrtPCR for AT1A and AT1B receptors. Acidic ribosomal protein-1 (ARP1) as control. n=6. (C) Luciferase promoter assays for SRF-dependent gene transcription in the presence of myocardin and constitutively active (CA) or kinase-dead (KD) CaMKII. The amount of co-transfected CaMKII plasmid is indicated in ng. n=3 * p<0.05 compared to WT. Unpaired, two-tailed t-tests were performed for (A) and (B), Ordinary one-Way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test for (C).

Numerous transcriptional pathways with potential relevance for remodeling are activated by Ang-II, including c-fos, NF-κB and the master regulator serum response factor (SRF). CaMKII directly regulates VSMC gene transcription through control of several transcription factors and regulators, for example MEF2 and CREB [37–39], yet its role in SRF regulation is incompletely studied. We tested the effect of CaMKII on SRF-dependent gene transcription using an SRF promoter assay in 293T cells. The co-expression of a constitutively active (CA) mutant of CaMKII suppressed SRF promoter activity, whereas the co-transfection of a kinase-dead (KD) CaMKII mutant had no effect (Figure 6C). Thus, CaMKII suppresses SRF-dependent gene transcription. Taken with the gene expression data from mesenteric arteries, these data suggest that CaMKII inhibition in differentiated VSMC in the vascular wall increases expression of contractile proteins concomitant with maintenance of a contractile VSMC phenotype.

4. DISCUSSION

Herein, we demonstrate that CaMKII is activated under chronic Ang-II infusion in the mesenteric vascular wall. CaMKII inhibition in VSMC enhanced constriction to agonists and increased the thickness of the arterial wall after chronic Ang-II infusion, resulting in a greater media/lumen ratio and decreased circumferential wall stress. In line with these findings, we detected higher mRNA and protein levels of structural proteins with a decrease in proliferation markers under CaMKII inhibition. As a potential mechanism, SRF-dependent promoter activity was inhibited with CaMKII overexpression. These data identify CaMKII as a regulator of VSMC remodeling in Ang-II hypertension in vivo.

The implications of structural remodeling for vascular contractility in hypertension have been studied for decades [40]. Folkow proposed in the past that repeated episodes of blood pressure elevation elicit vascular remodeling that enhances vasoconstriction and sustains hypertension [24]. Here, we report that remodeling and constriction are concordantly increased with CaMKII inhibition. These data are not in agreement with the concept proposed by Folkow given that we previously reported that blood pressure is lower in TG SM-CaMKIIN mice following chronic Ang-II infusion as compared to WT mice [23]. However, other studies have emerged that that do not align with this concept [25]. These data demonstrate that the biological processes behind remodeling versus altered contractility may be multifaceted and also depend on the vascular bed. The increase in wall thickness in hypertensive TG SM-CaMKIIN mice may be due to either vascular remodeling or reduced distensibility of mesenteric arteries. Since the passive diameter was not significantly different, we believe that our findings are consequent to remodeling of similar amounts of wall material.

As a potential mechanism, we detected increased expression of smooth muscle structural proteins under CaMKII inhibition. CaMKII can regulate transcription of structural muscle proteins directly by phosphorylating target transcription factors such as NFAT and CREB or indirectly through controlling intracellular Ca2+ levels [17, 38, 39, 41–43]. Here, we provide novel evidence for a role of CaMKII in the repression of the key transcriptional regulator SRF in VSMC. In previous studies, CaMKII phosphorylation enhanced DNA binding of SRF in skeletal muscle [15], whereas the related calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV repressed SRF activity in cardiac myocytes [44]. Alternatively, CaMKII inhibition may exert its actions through regulation of mRNA stability [20, 45]. Of note, we previously reported that CaMKII inhibition in the aortic wall in vivo promotes the expression of mRNA’s related to contractile muscle fiber [23]. Conceptually, these data are well aligned with increased vasoconstriction and remodeling as observed in this study and reports that prolonged vasoconstriction can enhance inward remodeling through processes related to VSMC structural proteins, such as actin polymerization [46]. Since CaMKII inhibition reduced wall stress in mesenteric arteries from hypertensive animals, we postulate that it may prevent the potentially damaging effects of long-term hypertension in humans.

Similar to its well-characterized role in myocardial hypertrophy, CaMKII has been proposed to regulate Ang-II-induced smooth muscle cell hypertrophy in cultured aortic smooth muscle cells [37, 47]. However, these data cannot be directly related to our findings. In vivo remodeling by Ang-II differs between vascular beds and is modulated by blood pressure, blood flow and sympathetic activity and measured under pressurized conditions that are not recapitulated in cultured cells. Moreover, VSMC undergo profound changes in protein expression profiles, including CaMKII isoforms, when isolated from the vascular wall and grown in culture [48]. In this study, Ang-II infusion led to relatively minor changes in CaMKII isoform expression compared to other disease models or as seen after cell isolation [19, 20, 48]. Emerging data that CaMKII isoforms have divergent [21], if not opposing functions imply that CaMKII signaling is cell- and context-specific. These data also demonstrate that a dissection of CaMKII function in vascular disease requires a careful alignment of models and discussion of the physiologic context.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kristina W. Thiel for assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by funding from the VA Office of Research and Development (1BX000163) and NIH (RO1 HL 108932) (IMG). Further funding was provided through VA 1BX000543 (KGL), NIH T32 HL007121 (AMP) and NIH P01 HL084207 (CDS).

The content of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the granting agencies.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mulvany MJ. Small artery remodeling in hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2002;4:49–55. doi: 10.1007/s11906-002-0053-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aalkjaer C, Heagerty AM, Petersen KK, Swales JD, Mulvany MJ. Evidence for increased media thickness, increased neuronal amine uptake, and depressed excitation--contraction coupling in isolated resistance vessels from essential hypertensives. Circ Res. 1987;61:181–186. doi: 10.1161/01.res.61.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiffrin EL, Deng LY, Larochelle P. Blunted effects of endothelin upon small subcutaneous resistance arteries of mild essential hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 1992;10:437–444. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199205000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreau P, d’Uscio LV, Shaw S, Takase H, Barton M, Luscher TF. Angiotensin II increases tissue endothelin and induces vascular hypertrophy: reversal by ET(A)-receptor antagonist. Circulation. 1997;96:1593–1597. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.5.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parker SB, Wade SS, Prewitt RL. Pressure mediates angiotensin II-induced arterial hypertrophy and PDGF-A expression. Hypertension. 1998;32:452–458. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rizzoni D, Porteri E, Boari GE, De Ciuceis C, Sleiman I, Muiesan ML, Castellano M, Miclini M, Agabiti-Rosei E. Prognostic significance of small-artery structure in hypertension. Circulation. 2003;108:2230–2235. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000095031.51492.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neves MF, Virdis A, Schiffrin EL. Resistance artery mechanics and composition in angiotensin II-infused rats: effects of aldosterone antagonism. J Hypertens. 2003;21:189–198. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200301000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thybo NK, Stephens N, Cooper A, Aalkjaer C, Heagerty AM, Mulvany MJ. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on small arteries of patients with previously untreated essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1995;25:474–481. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.4.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiffrin EL, Deng LY, Larochelle P. Effects of a beta-blocker or a converting enzyme inhibitor on resistance arteries in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 1994;23:83–91. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen KL, Mulvany MJ. Vasodilatation, not hypotension, improves resistance vessel design during treatment of essential hypertension: a literature survey. J Hypertens. 2001;19:1001–1006. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200106000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erickson JR, He BJ, Grumbach IM, Anderson ME. CaMKII in the cardiovascular system: sensing redox states. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:889–915. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham ST, Benscoter H, Schworer CM, Singer HA. In situ Ca2+ dependence for activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2506–2513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mortality after 10 1/2 years for hypertensive participants in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Circulation. 1990;82:1616–1628. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraham ST, Benscoter HA, Schworer CM, Singer HA. A role for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade of cultured rat aortic vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1997;81:575–584. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fluck M, Booth FW, Waxham MN. Skeletal muscle CaMKII enriches in nuclei and phosphorylates myogenic factor SRF at multiple sites. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:488–494. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lamping KG, Faraci FM. Role of sex differences and effects of endothelial NO synthase deficiency in responses of carotid arteries to serotonin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:523–528. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.4.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min LJ, Mogi M, Tamura K, Iwanami J, Sakata A, Fujita T, Tsukuda K, Jing F, Iwai M, Horiuchi M. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor-associated protein prevents vascular smooth muscle cell senescence via inactivation of calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T cells pathway. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:798–809. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minami K, Fukuzawa K, Nakaya Y. Protein kinase C inhibits the Ca(2+)-activated K+ channel of cultured porcine coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;190:263–269. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li W, Li H, Sanders PN, Mohler PJ, Backs J, Olson EN, Anderson ME, Grumbach IM. The multifunctional Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II delta (CaMKIIdelta) controls neointima formation after carotid ligation and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through cell cycle regulation by p21. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7990–7999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.163006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott JA, Klutho PJ, El Accaoui R, Nguyen E, Venema AN, Xie L, Jiang S, Dibbern M, Scroggins S, Prasad AM, Luczak ED, Davis MK, Li W, Guan X, Backs J, Schlueter AJ, Weiss RM, Miller FJ, Anderson ME, Grumbach IM. The Multifunctional Ca(2+)/Calmodulin-Dependent Kinase IIdelta (CaMKIIdelta) Regulates Arteriogenesis in a Mouse Model of Flow-Mediated Remodeling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71550. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saddouk FZ, Sun LY, Liu YF, Jiang M, Singer DV, Backs J, Van Riper D, Ginnan R, Schwarz JJ, Singer HA. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-gamma (CaMKIIgamma) negatively regulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and vascular remodeling. FASEB J. 2016;30:1051–1064. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-279158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prasad AM, Nuno DW, Koval OM, Ketsawatsomkron P, Li W, Li H, Shen FY, Joiner ML, Kutschke W, Weiss RM, Sigmund CD, Anderson ME, Lamping KG, Grumbach IM. Differential control of calcium homeostasis and vascular reactivity by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II. Hypertension. 2013;62:434–441. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prasad AM, Morgan DA, Nuno DW, Ketsawatsomkron P, Bair TB, Venema AN, Dibbern ME, Kutschke WJ, Weiss RM, Lamping KG, Chapleau MW, Sigmund CD, Rahmouni K, Grumbach IM. Calcium/Calmodulin-Dependent Kinase II Inhibition in Smooth Muscle Reduces Angiotensin II-Induced Hypertension by Controlling Aortic Remodeling and Baroreceptor Function. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.001949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folkow B. Physiological aspects of primary hypertension. Physiol Rev. 1982;62:347–504. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1982.62.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L, Feng D, Luo Z, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS, Lai EY. Remodeling of Afferent Arterioles From Mice With Oxidative Stress Does Not Account for Increased Contractility but Does Limit Excessive Wall Stress. Hypertension. 2015;66:550–556. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King AJ, Osborn JW, Fink GD. Splanchnic circulation is a critical neural target in angiotensin II salt hypertension in rats. Hypertension. 2007;50:547–556. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.090696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boucher P, Gotthardt M, Li WP, Anderson RG, Herz J. LRP: role in vascular wall integrity and protection from atherosclerosis. Science. 2003;300:329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1082095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang R, Khoo MS, Wu Y, Yang Y, Grueter CE, Ni G, Price EE, Jr, Thiel W, Guatimosim S, Song LS, Madu EC, Shah AN, Vishnivetskaya TA, Atkinson JB, Gurevich VV, Salama G, Lederer WJ, Colbran RJ, Anderson ME. Calmodulin kinase II inhibition protects against structural heart disease. Nat Med. 2005;11:409–417. doi: 10.1038/nm1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bader H. Dependence of wall stress in the human thoracic aorta on age and pressure. Circ Res. 1967;20:354–361. doi: 10.1161/01.res.20.3.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamping K, Faraci F. Enhanced vasoconstrictor responses in eNOS deficient mice. Nitric oxide : biology and chemistry / official journal of the Nitric Oxide Society. 2003;8:207–213. doi: 10.1016/s1089-8603(03)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang D, Chang PS, Wang Z, Sutherland L, Richardson JA, Small E, Krieg PA, Olson EN. Activation of cardiac gene expression by myocardin, a transcriptional cofactor for serum response factor. Cell. 2001;105:851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00404-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mattiazzi A, Vittone L, Mundina-Weilenmann C, Said M. Phosphorylation of the Thr17 residue of phospholamban. New insights into the physiological role of the CaMK-II pathway of phospholamban phosphorylation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;853:280–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stull JT, Tansey MG, Tang DC, Word RA, Kamm KE. Phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase: a cellular mechanism for Ca2+ desensitization. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;127–128:229–237. doi: 10.1007/BF01076774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tansey MG, Luby-Phelps K, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Ca(2+)-dependent phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase decreases the Ca2+ sensitivity of light chain phosphorylation within smooth muscle cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1994;269:9912–9920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tansey MG, Word RA, Hidaka H, Singer HA, Schworer CM, Kamm KE, Stull JT. Phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase by the multifunctional calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in smooth muscle cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1992;267:12511–12516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sparks MA, Parsons KK, Stegbauer J, Gurley SB, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Fortner CN, Snouwaert J, Raasch EW, Griffiths RC, Haystead TA, Le TH, Pennathur S, Koller B, Coffman TM. Angiotensin II type 1A receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells do not influence aortic remodeling in hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;57:577–585. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.165274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H, Li W, Gupta AK, Mohler PJ, Anderson ME, Grumbach IM. Calmodulin kinase II is required for angiotensin II-mediated vascular smooth muscle hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H688–698. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01014.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MacDonnell SM, Weisser-Thomas J, Kubo H, Hanscome M, Liu Q, Jaleel N, Berretta R, Chen X, Brown JH, Sabri AK, Molkentin JD, Houser SR. CaMKII negatively regulates calcineurin-NFAT signaling in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2009;105:316–325. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.194035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Sun LY, Singer DV, Ginnan R, Singer HA. CaMKIIdelta-dependent inhibition of cAMP-response element-binding protein activity in vascular smooth muscle. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:33519–33529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.490870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Folkow B. “Structural factor” in primary and secondary hypertension. Hypertension. 1990;16:89–101. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.16.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nieves-Cintron M, Amberg GC, Navedo MF, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. The control of Ca2+ influx and NFATc3 signaling in arterial smooth muscle during hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15623–15628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808759105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki E, Nishimatsu H, Satonaka H, Walsh K, Goto A, Omata M, Fujita T, Nagai R, Hirata Y. Angiotensin II induces myocyte enhancer factor 2- and calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T cell-dependent transcriptional activation in vascular myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;90:1004–1011. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000017629.70769.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wada H, Hasegawa K, Morimoto T, Kakita T, Yanazume T, Abe M, Sasayama S. Calcineurin-GATA-6 pathway is involved in smooth muscle-specific transcription. The Journal of cell biology. 2002;156:983–991. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200106057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis FJ, Gupta M, Camoretti-Mercado B, Schwartz RJ, Gupta MP. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase activates serum response factor transcription activity by its dissociation from histone deacetylase, HDAC4. Implications in cardiac muscle gene regulation during hypertrophy. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:20047–20058. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209998200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atkins CM, Nozaki N, Shigeri Y, Soderling TR. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein-dependent protein synthesis is regulated by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2004;24:5193–5201. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0854-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staiculescu MC, Galinanes EL, Zhao G, Ulloa U, Jin M, Beig MI, Meininger GA, Martinez-Lemus LA. Prolonged vasoconstriction of resistance arteries involves vascular smooth muscle actin polymerization leading to inward remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;98:428–436. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pang J, Yan C, Natarajan K, Cavet ME, Massett MP, Yin G, Berk BC. GIT1 mediates HDAC5 activation by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:892–898. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.161349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.House SJ, Ginnan RG, Armstrong SE, Singer HA. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-delta isoform regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C2276–2287. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00606.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]